Publisher's Note: There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

Key Points

The 3 endothelial secretory pathways—constitutive, basal, and regulated—release VWF in different multimeric states.

Apical- and basolaterally-released VWF follow different secretory pathways, thus releasing differentially multimerized protein.

Abstract

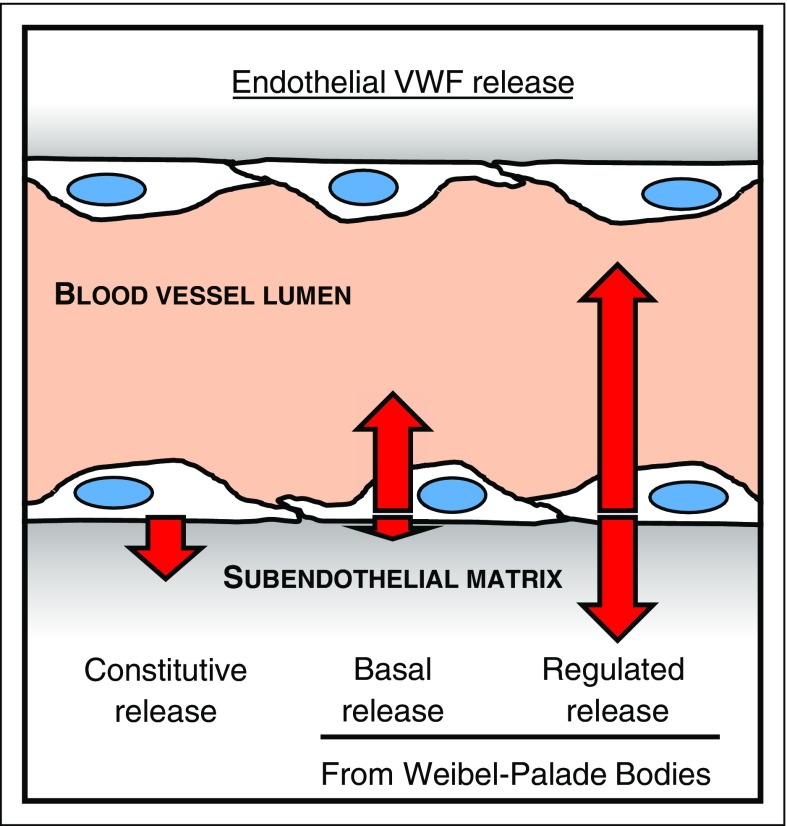

The von Willebrand factor (VWF) synthesized and secreted by endothelial cells is central to hemostasis and thrombosis, providing a multifunctional adhesive platform that brings together components needed for these processes. VWF secretion can occur from both apical and basolateral sides of endothelial cells, and from constitutive, basal, and regulated secretory pathways, the latter two via Weibel-Palade bodies (WPB). Although the amount and structure of VWF is crucial to its function, the extent of VWF release, multimerization, and polarity of the 3 secretory pathways have only been addressed separately, and with conflicting results. We set out to clarify these relationships using polarized human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) grown on Transwell membranes. We found that regulated secretion of ultra–large (UL)-molecular-weight VWF predominantly occurred apically, consistent with a role in localized platelet capture in the vessel lumen. We found that constitutive secretion of low-molecular-weight (LMW) VWF is targeted basolaterally, toward the subendothelial matrix, using the adaptor protein complex 1 (AP-1), where it may provide the bulk of collagen-bound subendothelial VWF. We also found that basally-secreted VWF is composed of UL-VWF, released continuously from WPBs in the absence of stimuli, and occurs predominantly apically, suggesting this could be the main source of circulating plasma VWF. Together, we provide a unified dataset reporting the amount and multimeric state of VWF secreted from the constitutive, basal, and regulated pathways in polarized HUVECs, and have established a new role for AP-1 in the basolateral constitutive secretion of VWF.

Introduction

von Willebrand factor (VWF) is a multimeric adhesive glycoprotein, synthesized and secreted by endothelial cells,1 that is involved in many vascular processes and is central to hemostasis and thrombosis.2 Circulating plasma and subendothelial VWF, both synthetized by vascular endothelial cells, have been ascribed different roles in hemostasis.3,4 How endothelial cells control these 2 very different functional pools of VWF has not been previously explored.

The multimeric form of secreted VWF largely dictates its hemostatic efficacy, because higher-molecular-weight VWF multimers have a much higher binding affinity for platelets.5 Endothelial cells have 2 differentiated surfaces: (1) apical, facing the vessel lumen; and (2) basolateral, facing the subendothelial extracellular matrix. Therefore, to fully understand how and where different multimeric forms of VWF make their contribution, we need to know not only how much is secreted apically vs basolaterally, but also by which one of 3 pathways it is delivered and the degree of multimerization found in each pool of this protein.

All 3 secretory pathways begin at the trans-Golgi network (TGN), where VWF is either packaged into nascent Weibel-Palade bodies (WPBs), distinctive rod-shaped regulated secretory organelles, or is secreted directly through the “constitutive” secretory pathway by nondescript small anterograde carriers.6 WPBs store VWF for regulated secretion upon endothelial activation, but they can also fuse and release VWF in the absence of activation, a process termed “basal” secretion to distinguish it from “constitutive” secretion,7,8 although both collect together in the supernatant of unstimulated cells. Low-molecular-weight–VWF (LMW-VWF) is secreted by the constitutive pathway, in contrast to the HMW-VWF released via stimulated WPBs,6,9 consistent with the need to control release of highly prothrombotic material.

Previous studies have addressed the polarity of VWF secretion, with conflicting results,10-14 partly because they were carried out before it was established that there were three pathways for secretion of VWF.8 van Buul-Wortelboer and collegues10 used human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) grown on collagen lattices to show that unstimulated (ie, basal plus constitutive) VWF release occurs at a 1:3 ratio (apical:basolateral), although the VWF quantified as basolateral release also took into account all the VWF cumulatively bound to the collagen fibers (80%), and so is an overestimation of the true basolateral rate of unstimulated release. When cells were stimulated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), most of the VWF was released to the apical side, with no detectable change in the amount released basolaterally. In the same, year Sporn and colleagues11 showed, using HUVECs grown on gelatin-coated polycarbonate membranes (3.0 μm pore size), that the amount of unstimulated VWF release (measured by 2-h metabolic labeling and analyzed by sodium dodecylsulfate [SDS]–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis) into apical or basolateral chambers was approximately equal and contained similar multimeric forms, including multimers of all sizes. When cells were stimulated with the calcium ionophore A23187, 90% of the additional VWF came out basolaterally, with only high multimeric VWF being released. The same pattern was reportedly seen with PMA stimulation.

A later study, again using HUVECs grown on a collagen matrix,12 showed that PMA-stimulated release was largely apical, with no change to the levels of basolateral release compared with unstimulated cells. Another study measuring the polar release of a variety of different molecules secreted by endothelial cells, including VWF,13 showed that HUVECs grown for 10 days on uncoated polycarbonate membranes (pore size 0.4 μm) secreted unstimulated VWF at a 2:1 ratio (apical:basolateral). No stimulant was used in this study to measure regulated VWF release. One final study14 used the polar Madin-Darby Canine Kidney II (MDCK-II) epithelial cell line stably transfected with VWF cDNA to study VWF polar secretion. Here again, unstimulated VWF release accumulated at a 2:1 ratio (apical:basolateral) compared with a ratio for PMA stimulated release of 4:1. Finally, live cell imaging of individual regulated exocytic events has demonstrated fusion of WPB to both basolateral15 and apical surfaces.16 Although no comparative analysis was done, this provides confirmation that evoked secretion can occur from both domains.

Altogether, the direction of VWF secretion, by which pathway(s) it is released, and the multimeric state of the releasate at both surfaces are currently unclear. In particular, the relative multimeric state and the polarity of VWF secreted by the basal pathway have never been established. We therefore addressed all these issues together and in parallel.

Finally, the origin of plasma VWF, which is the best characterized pool of this molecule and is the pool assayed for diagnostic purposes, is unclear. Although it is expected to be generated from highly multimerized material that is then cleaved by ADAMTS-13 down to the multimeric pattern observed in plasma, whether it arises from basal or regulated exocytosis is yet unclear.

Not only is the basic description of VWF secretion confused, but the machinery for polarized targeting of these pathways in endothelial cells is also poorly understood. Because WPB are the regulated secretory VWF carriers, and AP-1 is essential to their formation,17 this adaptor protein complex is a strong candidate to be in control of this pathway. Loss of AP-1 also increases unstimulated secretion, but whether this affects constitutive, basal, or both pathways is unclear. Furthermore, AP-1 is thought to mainly play a role in basolateral targeting in polarized epithelial cells,18 and its role in polar trafficking in endothelial cells has never been explored.

Here, we report the polarity and multimeric state of VWF secretion from constitutive, basal and regulated secretory pathways in polarized HUVECs, establish a new role for AP-1 in the constitutive secretion of VWF, and suggest a likely origin for plasma VWF.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

HUVECs pooled from multiple donors were obtained from Lonza (Lonza Walkersville, Walkersville, MD). Cells were maintained in HUVEC growth medium, composed of M199 (Gibco, Life Technologies) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (Biosera), 30 μg/mL endothelial cell growth supplement from bovine neural tissue, and 10 U/mL heparin (both from Sigma-Aldrich) and used within 4 passages.

Secretion assay and VWF quantification by ELISA

Secreted VWF was obtained by incubating confluent cells in serum-free (SF) medium (M199, 0.1 mg/mL BSA, 10mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.4) for 60 minutes. The medium was collected and the cells incubated further with SF medium containing secretagogues for 30 minutes. The remaining cells were then lysed to determine total VWF levels. Relative amounts of VWF were determined by sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as previously described.19

Additional materials and methods can be found in the Supplemental material, available on the Blood Web site.

Results

Multimeric states of endothelial cell VWF secreted from 3 different pathways

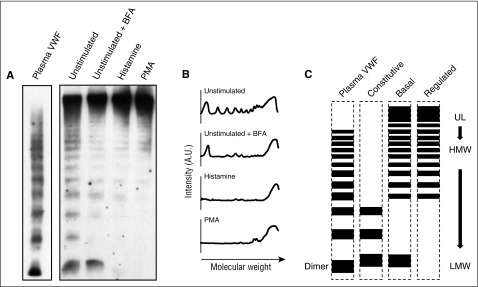

Because the multimeric state of secreted VWF largely dictates its function, we determined the multimeric pattern of VWF secreted by the 3 known pathways from endothelial cells on plastic dishes, comparing releasate collected from confluent HUVECs and running the same amount of VWF in each sample (as measured by ELISA) on an SDS/agarose gel. Brefeldin A8 (BFA), known to block direct constitutive release from the Golgi, was used to distinguish between constitutive and basal VWF release collected during unstimulated conditions; and 2 different widely used secretagogues, histamine and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), were used to stimulate regulated release. As previously reported,20,21 secretagogue-stimulated secretion, termed “regulated” release, was mainly composed of ultralarge (UL) and very-high-molecular-weight multimers (HMW-VWF), whereas unstimulated release contained a broad range of multimer sizes including a higher proportion of low-molecular-weight multimers (LMW-VWF) and prominent dimer bands (Figure 1A-B). When BFA was used to block constitutive secretion, leaving only basal VWF releasate, a multimeric pattern very similar to that of stimulated samples was observed with the exception that a strong dimer band was always present.

Figure 1.

Multimeric states of endothelial cell VWF secreted from 3 different pathways. (A) Representative multimer pattern of secreted VWF collected for 30 minutes from unstimulated HUVECs, treated with 5 μM of Brefeldin A (+BFA) for 1 hour before and during secretion collection, treated with 100 μM histamine or 100 ng/mL of PMA. VWF ELISA was used to measure the amount of VWF secreted in all conditions and the same units of VWF were loaded on an SDS/agarose gel (migrations shown from top to bottom). A parallel sample of human plasma is shown for comparison (Plasma VWF). Relative VWF amount ratios in this experiment are 1:1:5:16 = constitutive:basal:histamine:PMA. (B) Representative line plots from the multimer patterns shown in (A). A.U., arbitrary units. (C) Diagram of multimer patterns of plasma VWF and VWF secreted via the constitutive, basal, and regulated secretory pathways from endothelial cells. UL, ultralarge; HMW, high-molecular-weight; LMW, low-molecular-weight.

These patterns suggest that although both are released during unstimulated conditions, constitutive and basally secreted VWF are differently multimerized and so could have very different functions. At the same time, although both are believed to arise from WPBs, basal and regulated VWF also have different multimeric patterns, namely the presence of a dimer band in basal secretion, also suggesting a significant difference between these 2 pools of VWF (Figure 1C).

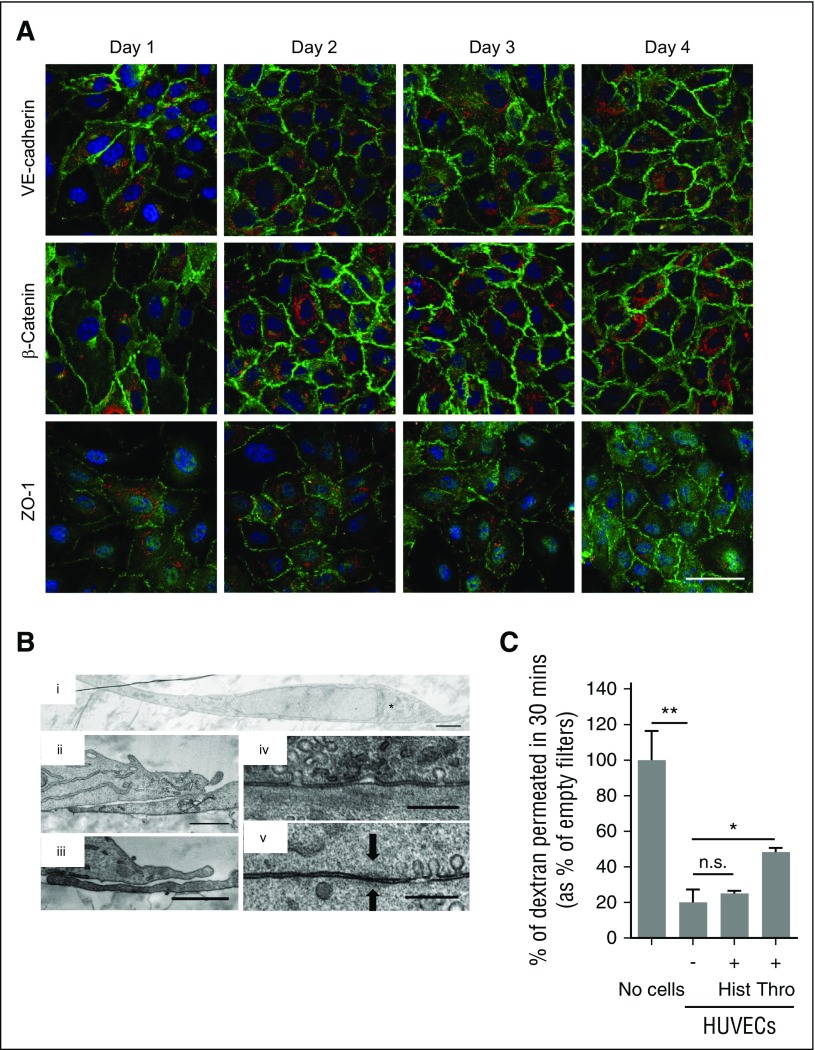

HUVECs form a tight monolayer on Transwell membranes

To study the polarity of VWF secretion, we first established the conditions for filter-grown HUVECs to form a confluent polar monolayer. HUVEC seeded at a density of 105 cells per cm2 on polyester membranes (pore size 0.4 μm) formed a continuous monolayer within 24 hours. These cells are tightly packed and acquire tight junction and adherent junction markers, such as VE-cadherin, β-catenin, and ZO-1 (Figure 2A), which are retained for several days post seeding. HUVECs are extremely thin cells (3-4 μm at their thickest) (Figure 2Bi), contain overlapping edges (Figure 2Bii-iii), and form tight junctions between neighboring cells (Figure 2Biv-v). Grown under these conditions, HUVEC monolayers form a barrier to diffusion (Figure 2C). As previously described, treatment of confluent HUVEC monolayers with thrombin opened gaps between cells,22 whereas treatment with 100 μM histamine for 30 minutes did not23 (supplemental Figures 1 and 3).

Figure 2.

Confluent HUVECs on polyester membranes form a polar monolayer. (A) Immunofluorescence of confluent HUVECs grown on polyester membranes for the times indicated (days) and stained for the cell’s nucleus (DAPI, blue); VWF (red); and VE-cadherin, β-catenin, or ZO-1 (green). Scale bar represents 50 μm. (B) TEM of a cross-section of a HUVEC (i) with the TGN to the right of the nucleus (*). Two examples of TEM cross-sections of overlapping tips between neighboring HUVECs (ii-iii) and the close contact formed between the cell membranes of 2 adjacent cells (iv-v) with “fuzz”-like structure typical of tight junctions in epithelial cells (arrows). Scale bar: i, 2 μm; ii-iii, 1 μm; iv-v, 300 nm. (C) Dextran permeability assay, where 1 mg/mL of 40 kD-FITC-dextran was loaded on the apical chamber of empty membranes (No cells), 2-day confluent unstimulated HUVECs (-), or HUVECs treated with 100 μM histamine (+Hist) or 2.5 U/mL thrombin (+Thro) to open extracellular pores. The amount of FITC-dextran in the basolateral chamber was measured after incubation with FITC-dextran in the apical chamber for 30 minutes. Mean of triplicate wells (with standard deviation [SD]), as percent of No cells control sample. *P < .05; **P < .005; n.s., not significant.

Constitutive, basal, and regulated VWF polar release

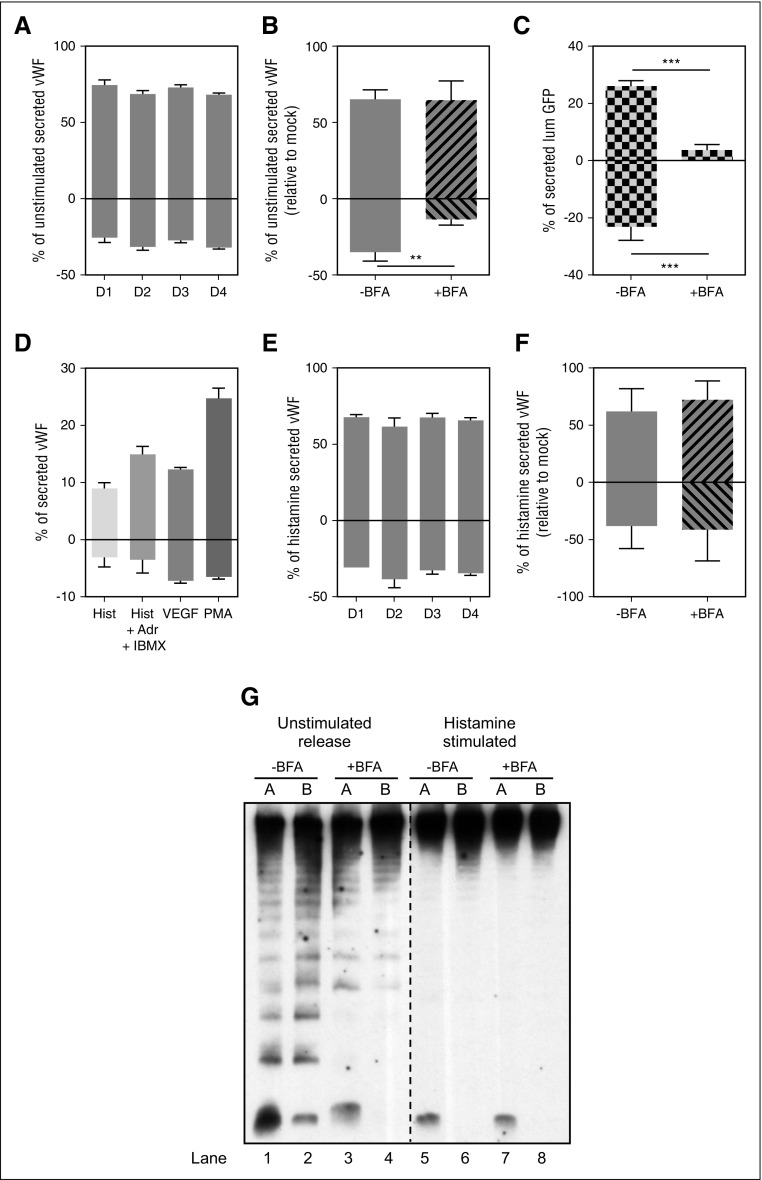

To measure unstimulated secretion, confluent HUVECs were washed and incubated in SF medium for 1 hour, and then supernatant collected from the apical and basolateral chambers were assayed for the amount of VWF by ELISA. We found at least twice as much VWF accumulated apically compared with that released basolaterally, and this ratio was maintained by cells grown for several days (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Polarity of VWF secretion. (A) Unstimulated VWF secretion on Transwell membranes of HUVECs grown for the time indicated (in days), expressed as a percent of secreted VWF from the total VWF in each sample (secreted plus lysate). Results standardized to D1 sample. Representative experiment, mean of 3 replicates with SD. (B) Unstimulated VWF secretion from HUVECs grown on Transwell membranes for 2 days. Cells were either left untreated (-BFA) or were treated with 5 μM of Brefeldin A (+BFA) for 1 hour before and during secretion collection from both chambers. Results standardized to control -BFA sample. Mean of 3 independent experiments with standard error of the mean (SEM). (**P < .005). (C) lumGFP secretion on Transwell membranes. HUVECs were nucleofected with lumGFP construct and seeded on Transwell membranes for 30 hours before secretion assay. Cells were treated with either Control (-BFA) or 5 μM of Brefeldin A (+BFA) for 1 hour before and during secretion collection from both chambers. Amount of lumGFP secreted expressed as a percent of total GFP in each sample (secreted plus lysate). Representative experiment reflects the mean of 3 replicates with SD. (***P < .0005). (D) Stimulated VWF secretion from HUVECs grown on Transwell membranes for 2 days. Cells were stimulated with either 100 μM histamine (Hist), 100 μM histamine plus 100 μM adrenaline plus 100 mM IBMX (Hist +Adr +IBMX), 40 ng/mL vascular endothelial growth factor, or 100 ng/mL PMA for 30 minutes while secreted VWF was collected from both chambers. Amount of VWF secreted expressed as a percent of total VWF in each sample (secreted plus lysate). Representative experiment reflects the mean of 3 replicates with SD. (E) Histamine VWF secretion from HUVECs grown on Transwell membranes for the time indicated (in days), expressed as a percent of total VWF in each sample (secreted plus lysate), relative to control (D1) sample. Results standardized to D1 sample. Representative experiment, mean of 3 replicates with SD. (F) Histamine VWF secretion from HUVECs grown on Transwell membranes for 2 days. Cells were treated with either control (-BFA) or 5 μM of Brefeldin A (+BFA) for 1 hour before and during 30 minutes 100 μM histamine stimulation and secretion collection from both chambers. Results standardized to control -BFA samples. Mean of 3 independent experiments with SEM. (G) Representative multimer pattern of secreted VWF collected from unstimulated and histamine-stimulated HUVECs. Cells were treated with either control (-BFA) or 5 μM of Brefeldin A (+BFA) for 1 hour before and during VWF secretion collection in both chambers. Unstimulated secretion was collected for 1 hour and 100 μM histamine stimulated secretion was collected for 30 minutes. The same units of VWF (as measured by ELISA) were loaded for all samples. VWF ELISA quantification corresponding to these samples is shown in (B) and (F). A, apical chamber; B, basolateral chamber. Lanes 1-4, unstimulated releasate; lanes 5-8, histamine-stimulated releasate.

Because VWF secreted with no externally added stimulant is from a mix of constitutive and basal secretory pathways, BFA8 was used to distinguish between these 2 pathways. Surprisingly, BFA only reduced basolaterally secreted VWF (Figure 3B), revealing that most constitutive VWF secretion is directed toward the basolateral side of endothelial cells. Conversely, VWF released during BFA treatment, and thus representing basal secretion, is secreted predominantly apically, with only a small fraction secreted basolaterally.

Because we were not expecting a constitutive VWF carrier to be targeted with any particular polarity, we determined whether a synthetic secretory cargo lacking any targeting information would also be targeted basolaterally in this cell system. To address this, HUVECs were transfected with lumGFP,24 a synthetic cargo that has been shown to be secreted via the constitutive pathway in endothelial cells.25 lumGFP secretion from membrane-grown cells was collected from both apical and basolateral chambers, and a GFP ELISA showed equal amounts of lumGFP released apically and basolaterally (Figure 3C). Critically, this release was effectively blocked in both directions by BFA. Because lumGFP is secreted in a nonpolarized fashion in polarized endothelial cells, this suggests that VWF constitutive secretion is dependent on active sorting into basolaterally targeted carriers.

To establish the polarity of VWF secreted via the regulated pathway, cells on membranes were stimulated with various secretagogues. In all cases, >70% of secreted VWF accumulated apically (Figure 3D), and this same pattern was unchanged irrespective of how long the cells were grown on filters before assay (Figure 3E). As predicted, BFA did not change the pattern of regulated (ie, stimulated minus unstimulated) VWF secretion (Figure 3F).

The degree of multimerization seen in VWF being secreted from the different pathways in different directions was then analyzed. Equivalent amounts (units) of VWF in each sample (as measured by ELISA) were loaded and analyzed by SDS/agarose gel electrophoresis. Although our ELISA results predicted that unstimulated apical VWF releasate should come mostly from basal secretion, composed of mostly UL-VWF multimers together with a dimer band, we still do see a high proportion of LMW-VWF in this sample, which disappears with BFA (Figure 3G, lanes 1 and 3). This suggests that unstimulated apical VWF releasate is composed of mostly of UL multimeric basal VWF but also contains a small amount of constitutive VWF (ie, BFA sensitive), which, with its LMW-VWF multimers, is probably underestimated in an ELISA and may be overrepresented on a gel.

Our ELISA results also suggest that unstimulated basolateral VWF secretion is mainly composed of constitutive VWF, with a smaller proportion of basal secretion (Figure 3B). This is matched by the multimer gels, where LMW-VWF multimers, which disappear with BFA, are seen along with the basally secreted UL-VWF bands (Figure 3G, lanes 2 and 4).

We also noticed that when BFA was used, leaving only basal VWF, a strong dimer band remained in the apical unstimulated releasate but, we were surprised to find, disappeared from the basolateral sample (Figure 3G, lanes 3 and 4). Further, in the histamine-stimulated samples, along with the expected UL-VWF multimers, a dimer band unpredictably appeared in the apically secreted material (Figure 3G, lanes 5 and 7). We currently have no explanation for this minor but surprising and consistently present phenomena.

AP-1 and VWF polar targeting

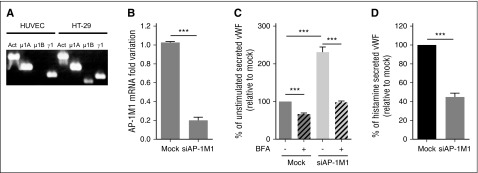

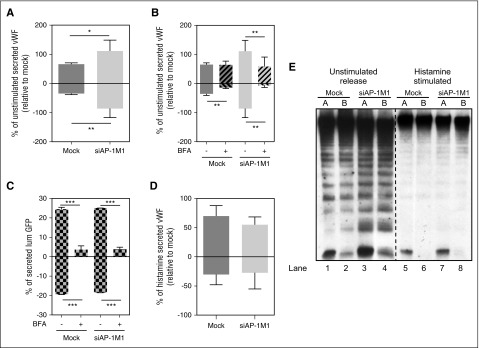

Most studies investigating the role of AP-1 in polarized targeting have done so by knocking out or downregulating the amount of the AP-1μ1 subunit, one of the core subunits of AP-1. Most of this work has investigated the role of the epithelial-specific26 AP-1μ1B subunit, and although HUVECs do not express this transcript (Figure 4A), they do express the more ubiquitous AP-1μ1A variant, also implicated in polarized trafficking in some studies.18 Here we used specific siRNA to effectively downregulate AP-1μ1A in HUVECs (herein referred to as “siAP-1M1”) using 2 rounds of nucleofection (Figure 4B). Similar to previous results from our laboratory using a VWF-expressing HEK293 cell model,17 downregulation of AP-1μ1A in HUVECs impairs WPB formation (supplemental Figure 2), with a resulting increase in unstimulated VWF secretion (Figure 4C, nonstriped bars) plus a decrease in stimulated VWF release (Figure 4D), when cells were grown in plastic wells. Critically, this was not caused by Golgi fragmentation in siAP-1M1–treated cells,27,28 (supplemental Figure 2) because we know this would affect WPB biogenesis.29 Using BFA, we can also now show that most of this increase in unstimulated VWF release in siAP-1M1–treated cells is caused by an increase in secretion via the constitutive pathway, because a larger proportion was blocked with BFA (Figure 4C). These results confirm that AP-1 is necessary for the sorting of VWF into WPB, and suggest that if this is disrupted, then the displaced VWF is continuously secreted through the constitutive pathway.

Figure 4.

AP-1 regulates VWF sorting into WPBs in HUVECs. (A) PCR bands to detect the presence of AP-1 subunits in HUVECs and HT-29 cells. Primers specific for Actin (Act), AP-1μ1A (μ1A), AP-1μ1B (μ1B), and AP-1γ1 (γ1) were used for amplification of cDNA made from extracted RNA from cell lysates. (B) Quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction measuring the efficiency of mRNA downregulation of the AP-1μ1A subunit in HUVECs after 2 rounds of nucleofection, with siRNA specifically targeting AP-1μ1A (siAP-1M1), 2 days apart. Mean of 12 experiments with SEM (***P < .0005). (C) Unstimulated VWF secretion on plastic of HUVECs either Mock-nucleofected or nucleofected with siAP-1M1. Cells were treated with either Control (-BFA) or 5 μM of Brefeldin A (+BFA) for 1 hour before and during VWF secretion collection. Results standardized to Mock-BFA samples. Mean of 5 independent experiments with SEM. (***P < .0005). (D) Histamine (100 μM)-stimulated VWF secretion on plastic of HUVECs either Mock-nucleofected or nucleofected with siAP-1M1. Results standardized to Mock samples. Mean of 5 independent experiments with SEM. ***P < .0005.

To determine whether AP-1 is also involved in the polarized targeting of VWF from the different secretory pathways, during the second round of siRNA nucleofection, HUVECs were seeded onto filters and allowed to grow for 2 days. Importantly, siAP-1M1 treatment did not alter monolayer permeability, even after histamine stimulation (supplemental Figure 3). Secreted VWF was collected and assayed by ELISA, revealing an increase in the total amount of unstimulated VWF secreted, as is seen on plastic-grown cells (Figure 5A, total bars). As with cells grown on plastic (Figure 4C), this increase reflected a rise in the amount of VWF secreted via the constitutive pathway (Figure 5B, larger proportion blocked by BFA treatment). Critically, as opposed to control cells, where constitutive secretion of VWF is mostly basolateral, in siAP-1M1–treated cells it is secreted in both directions, losing its exclusive basolateral targeting. Ablation of another AP-1 subunit (γ-adaptin) confirmed these results (supplemental Figure 4), strongly suggesting that AP-1 is involved in the basolateral targeting of constitutive VWF carriers in endothelial cells.

Figure 5.

AP-1 regulates basolateral sorting of VWF constitutive carriers. (A) Unstimulated VWF secretion from HUVECs grown on Transwell membranes either Mock-nucleofected or nucleofected with siRNA specifically targeting AP-1μ1A (siAP-1M1). Results standardized to Mock samples. Mean of 5 independent experiments with SEM. *P < .05, **P < .005. (B) Unstimulated VWF secretion from HUVECs grown on Transwell membranes either Mock-nucleofected or nucleofected with siAP-1M1. Cells were treated with either control (-BFA) or 5 μM of Brefeldin A (+BFA) for 1 hour before and during VWF secretion collection. Results standardized to Mock samples. Mean of 3 independent experiments with SEM. **P < .005. (C) lumGFP secretion on Transwell membranes. HUVECs were either Mock-nucleofected or nucleofected with siRNA specifically targeting AP-1μ1A (siAP-1M1), and lumGFP construct was added during the second round of nucleofection and seeded on Transwell membranes for 30 hours before secretion collection. Cells were treated with either Control (-BFA) or 5 μM of Brefeldin A (+BFA) for 1 h before and during secretion collection in both chambers. Amount of lumGFP secreted expressed as a percent of total GFP in each sample (secreted plus lysate). Mean of 3 replicates with SD. ***P < .0005. (D) Histamine (100 μM) stimulated VWF secretion from HUVECs grown on Transwell membranes either Mock-nucleofected or nucleofected with siRNA, specifically targeting AP-1μ1A (siAP-1M1). Results standardized to Mock samples. Mean of 7 independent experiments with SEM. (E) Representative multimer pattern of secreted VWF collected from unstimulated or 100 μM Histamine–stimulated HUVECs either Mock-nucleofected or nucleofected with siAP-1M1. Unstimulated secretion was collected for 1 hour and histamine-stimulated secretion was collected for 30 minutes. The same units of VWF (as measured by ELISA) were loaded for all samples. VWF ELISA quantification corresponding to these samples are shown in (A) and (D). A, apical chamber; B, basolateral chamber. Lanes 1-4, unstimulated releasate; lanes 5-8, histamine-stimulated releasate.

To confirm whether this effect on constitutive secretion was specific to VWF, we again used the lumGFP construct to check whether AP-1 had any effect on the polarity of its secretion. The amount, sensitivity to BFA, and polarity of lumGFP secretion (Figure 5C) were not affected in siAP-1M1–treated cells, confirming a specific effect of AP-1 on the polarity of VWF constitutive carriers and not a general function of this adaptor on all constitutive carriers in endothelial cells. The polarity of basal (Figure 5B, hatched bars) and regulated VWF release (Figure 5D) was not affected in siAP-1M1–treated cells, with the majority of VWF still being released apically.

Multimer gels of VWF secreted from siAP-1M1–treated cells were analyzed and, as predicted from the secretion assay results (Figure 5A,B,D), we observed little change in the multimeric state of VWF secreted from siAP-1M1–treated cells compared with control cells. The multimeric pattern from histamine-stimulated cells was identical and that from unstimulated cells was very similar when compared with control cells (Figure 5E), except for an increase in the proportion of LMW-VWF bands in the siAP-1M1 samples, because of the increase in the proportion of constitutively secreted VWF in these samples (Figure 5E, most clearly seen by the increase in tetramers and hexamers in lanes 3-4 vs 1-2). This was not unexpected because, in addition to the increased constitutive release, basal and even regulated exocytosis are both still occurring, albeit at reduced levels.

Discussion

In this study, we establish for the first time the relative amounts and multimeric states of VWF released through all 3 known secretory pathways: constitutive, basal, and regulated release. We show that constitutively secreted VWF is composed of mainly LMW-VWF multimers; that basally secreted VWF, originating from the continuous release of VWF from WPB in the absence of added stimuli, is composed of mostly UL-VWF multimers together with a prominent dimer band; and that regulated VWF release is exclusively composed of UL-VWF multimers (Figure 1). Since the discovery of the basal pathway for VWF secretion from endothelial cells,8 the multimeric state of this continuous source of VWF had not been previously established and thus its functional role has never been addressed. Our current findings suggest that the multimeric state of VWF secreted from the 3 pathways is different and so could have different physiologic functions.

We go further and establish the amount and multimeric states of VWF from all 3 pathways in a polar endothelial context. The need to revisit the polarity of VWF secretion, mainly investigated 25 years ago, first reflects that this analysis dates from before the clarification by Giblin et al,8 of the 3 possible secretory pathways taken by VWF (constitutive, basal, and regulated). Second, the literature from that time is somewhat confusing, with different results being presented. Finally, the relationship between all 3 pathways and the multimeric state of VWF has not been previously addressed, let alone in a polarized cell system. We have attempted to put all these aspects together into an overall comprehensive picture of polarized VWF secretion and multimerization using primary human endothelial cells.

We find that the largest amount of stimulated (regulated) VWF secretion occurs apically, with varying total amounts depending on the secretagogues used (Figure 6). This is in line with the majority of previous in vitro10,12,14 and in vivo studies.30 This form of secreted VWF is also composed of mainly UL-VWF multimers. This is in line with the currently accepted, yet experimentally unsupported, dogma that most highly multimerized VWF is secreted mainly toward the apical (lumen) surface of endothelial cells, which we now prove experimentally for the first time. The lumen of the blood vessel is where circulating platelets can be recruited by locally released UL-VWF upon stimulation, and where endothelial-anchored VWF strings can initiate a hemostatic event, in a tightly localized and controlled fashion.31 Thus, regulated VWF release can be thought of as the critical pool for emergency use only, where apically released VWF strings along with basolaterally released anchoring VWF are restricted to the site of injury, while being of the highest platelet-binding activity.

Figure 6.

The pathways of VWF secretion and their polarity. Diagram of a blood vessel showing the relative amount (length of arrows) and direction of secreted VWF from the 3 different secretory pathways from endothelial cells. The direction of VWF secreted either to the apical (vessel lumen) or the basolateral side (subendothelial matrix) of endothelial cells from each pathway is indicated by the direction of the arrows. Release from the constitutive pathway, which is Brefeldin A–sensitive, is exclusively to the basolateral side of endothelial cells, and is mostly composed of LMW-VWF multimers. Basal VWF release, the continuous release from WPBs, occurs mostly toward the apical side of endothelial cells, with a small amount secreted basolaterally, and is composed of UL-VWF multimer together with a dimer band. Regulated release, originating from WPB after a secretagogue stimulant, occurs predominantly to the apical side, with some release to the basolateral side, and is composed of exclusively UL-VWF multimers.

We also find that twice as much unstimulated VWF accumulated apically compared with that released basolaterally, in line with reports from Narahara et al13 and Hop et al.14 We go further and use BFA to distinguish between VWF released constitutively vs basally, observing for the first time that basal VWF secretion occurs predominately to the apical side of endothelial cells, with only a small fraction being secreted basolaterally (Figure 6). These findings suggest that this form of VWF, continuously secreted along the vascular tree could be the major source of plasma VWF. Once secreted from endothelial cells through the basal pathway, this UL-VWF form is cleaved by the endothelial secreted32 metalloprotease ADAMTS-13,31 generating the more intermediate VWF multimers found in plasma (Figure 1), allowing control of levels of highly prothrombotic VWF in circulation.

Most in vitro work on exocytosis has focused on regulated release, and the short collection times (15-60 minutes) used in analyses emphasize the relative amount of secretagogue-driven release, giving the impression of this being the main source of VWF in plasma. However, we suggest that this may be mistaken: if basal release is only 5% to 20% of secretagogue-driven secretion (depending on the secretagogue used) per unit of time, then for regulated and basal secretion to both generate an equal amount of circulating VWF, 5% to 20% of the WPB-containing endothelium would need to be activated at any given time—this seems extremely unlikely.

Our data are also consistent with the need for targeting of VWF into WPB for appropriate multimerization to occur during biosynthesis: both regulated and basal pathways release highly multimerized VWF, in contrast to the constitutive pathway. Why we see a significant dimer band in basally secreted VWF is as yet unclear, although the internal milieu of these 2 carriers (basal WPBs vs regulated WPBs) are likely to be different, perhaps having different retention times inside the cell that could potentially drive differential multimerization patterns. Whether the dimers only reflect the differential maturation of the 2 populations of WPB, or actively contribute to some difference in function is as yet unknown.

Previous findings from our laboratory (see supplemental Figure 4C in reference 29) and others31,33,34 have shown that unstimulated cells only rarely form VWF strings under flow. This is consistent with our proposed role for basal VWF, again suggesting that, although being of similar high multimeric states (except for the dimer band), basal and regulated VWF play different functional roles. Whether basally secreted VWF is incapable of producing strings or this difference simply reflects the exocytic mode of this secretory pathway is yet unknown: low numbers of randomly distributed exocytic events will preclude cooperative action in bringing together the material from more than one exocytic event that could well be needed to drive string formation.

The requirement to sustain a steady source of plasma VWF to maintain adequate hemostasis is crucial, as observed in patients with type 1 and type 3 von Willebrand disease.35 Basally released VWF provides such a source because it is (1) continuously secreted, (2) of a high multimeric state such that it could act as the precursor of plasma VWF, (3) does not produce VWF strings to initiate thrombus formation, and (4) is secreted mostly apically toward the vessel lumen, four critical requirements for an adequate and reliable source of circulating plasma VWF.

Our results also show that constitutive VWF release is, to our surprise, exclusively basolaterally targeted. We also report a novel role for AP-1 in this delivery, along with its known role in WPB biogenesis.17 This is in agreement with its long established role in basolateral targeting in epithelial cells. How AP-1 acts in sorting VWF at the TGN is puzzling. The AP complexes involved in sorting during the formation of clathrin-coated vesicles are generally recruited to membranes by binding to the cytoplasmic tails of integral transmembrane proteins.36 How then does VWF, a protein with no transmembrane domains, recruit AP-1? To date, there is no identified abundant integral membrane VWF-binding protein to recruit AP-1. We note that heterologous expression of VWF results in formation of WPB in some cells but not others,37 thus some cell-specific machinery must be in operation, but this elusive component has not yet been identified.

Finally: why is constitutively released VWF actively targeted for basolateral delivery? Substrate-bound VWF along with collagen is known to promote anchoring, at least in vitro, of circulating plasma VWF38,39 and platelets40 under shear flow, which is critical to producing a hemostatic plug during vascular injury when the entire endothelial layer has been lost and the subendothelial matrix is exposed to shear stress. We note that endothelial cells specifically target this material for incorporation into the matrix via AP-1, implying that this is not nonspecific leakage but a deliberate provision of this pool, and that the VWF provided in this way is of low multimeric state. Because the vast majority of in vitro studies investigating the role of immobilized VWF use human plasma as their source of VWF (which contains both LMW and HMW, but is devoid of UL multimers) it could be that constitutively secreted VWF from endothelial cells is itself the source of functional subendothelial VWF and/or it acts to increase the efficiency of recruitment of plasma VWF. Further in vitro studies comparing the functional differences when either UL-VWF or LMW-VWF is used as source material for matrix-bound VWF would help to dissect this issue.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Tom Carter for his generous gift of the pro-VWF peptide antibody, and the Cutler laboratory for valuable input and discussion, and for reading the manuscript.

This study was supported by grant MC-UU-12018/2 from the Medical Research Council of Great Britain (M.L.d.S. and D.F.C).

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: M.L.d.S. designed, performed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; and D.F.C. designed research and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Daniel F. Cutler, MRC Laboratory for Molecular Cell Biology and Cell Biology Unit, University College London, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BTD, United Kingdom; e-mail: d.cutler@ucl.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Metcalf DJ, Nightingale TD, Zenner HL, Lui-Roberts WW, Cutler DF. Formation and function of Weibel-Palade bodies. J Cell Sci. 2008;121(Pt 1):19–27. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruggeri ZM. The role of von Willebrand factor in thrombus formation. Thromb Res. 2007;120(Suppl 1):S5–S9. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reininger AJ. Function of von Willebrand factor in haemostasis and thrombosis. Haemophilia. 2008;14(Suppl 5):11–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2008.01848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sussman II, Rand JH. Subendothelial deposition of von Willebrand’s factor requires the presence of endothelial cells. J Lab Clin Med. 1982;100(4):526–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Federici AB, Bader R, Pagani S, Colibretti ML, De Marco L, Mannucci PM. Binding of von Willebrand factor to glycoproteins Ib and IIb/IIIa complex: affinity is related to multimeric size. Br J Haematol. 1989;73(1):93–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1989.tb00226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sporn LA, Marder VJ, Wagner DD. Inducible secretion of large, biologically potent von Willebrand factor multimers. Cell. 1986;46(2):185–190. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90735-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsuuchi L, Kelly RB. Constitutive and basal secretion from the endocrine cell line, AtT-20. J Cell Biol. 1991;112(5):843–852. doi: 10.1083/jcb.112.5.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giblin JP, Hewlett LJ, Hannah MJ. Basal secretion of von Willebrand factor from human endothelial cells. Blood. 2008;112(4):957–964. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-130740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai H-M, Nagel RL, Hatcher VB, Seaton AC, Sussman II. The high molecular weight form of endothelial cell von Willebrand factor is released by the regulated pathway. Br J Haematol. 1991;79(2):239–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1991.tb04528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Buul-Wortelboer MF, Brinkman HJ, Reinders JH, van Aken WG, van Mourik JA. Polar secretion of von Willebrand factor by endothelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;1011(2-3):129–133. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(89)90199-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sporn LA, Marder VJ, Wagner DD. Differing polarity of the constitutive and regulated secretory pathways for von Willebrand factor in endothelial cells. J Cell Biol. 1989;108(4):1283–1289. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.4.1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hakkert BC, Rentenaar JM, van Mourik JA. Monocytes enhance endothelial von Willebrand factor release and prostacyclin production with different kinetics and dependency on intercellular contact between these two cell types. Br J Haematol. 1992;80(4):495–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1992.tb04563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Narahara N, Enden T, Wiiger M, Prydz H. Polar expression of tissue factor in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994;14(11):1815–1820. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.11.1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hop C, Fontijn R, van Mourik JA, Pannekoek H. Polarity of constitutive and regulated von Willebrand factor secretion by transfected MDCK-II cells. Exp Cell Res. 1997;230(2):352–361. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.3431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erent M, Meli A, Moisoi N, et al. Rate, extent and concentration dependence of histamine-evoked Weibel-Palade body exocytosis determined from individual fusion events in human endothelial cells. J Physiol. 2007;583(Pt 1):195–212. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.132993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nightingale TD, White IJ, Doyle EL, et al. Actomyosin II contractility expels von Willebrand factor from Weibel-Palade bodies during exocytosis. J Cell Biol. 2011;194(4):613–629. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201011119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lui-Roberts WWY, Collinson LM, Hewlett LJ, Michaux G, Cutler DF. An AP-1/clathrin coat plays a novel and essential role in forming the Weibel-Palade bodies of endothelial cells. J Cell Biol. 2005;170(4):627–636. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200503054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gravotta D, Carvajal-Gonzalez JM, Mattera R, et al. The clathrin adaptor AP-1A mediates basolateral polarity. Dev Cell. 2012;22(4):811–823. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blagoveshchenskaya AD, Hannah MJ, Allen S, Cutler DF. Selective and signal-dependent recruitment of membrane proteins to secretory granules formed by heterologously expressed von Willebrand factor. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13(5):1582–1593. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-09-0462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sporn LA, Marder VJ, Wagner DD. von Willebrand factor released from Weibel-Palade bodies binds more avidly to extracellular matrix than that secreted constitutively. Blood. 1987;69(5):1531–1534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arya M, Anvari B, Romo GM, et al. Ultralarge multimers of von Willebrand factor form spontaneous high-strength bonds with the platelet glycoprotein Ib-IX complex: studies using optical tweezers. Blood. 2002;99(11):3971–3977. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-11-0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rabiet M-J, Plantier J-L, Rival Y, Genoux Y, Lampugnani MG, Dejana E. Thrombin-induced increase in endothelial permeability is associated with changes in cell-to-cell junction organization. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996;16(3):488–496. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.3.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andriopoulou P, Navarro P, Zanetti A, Lampugnani MG, Dejana E. Histamine induces tyrosine phosphorylation of endothelial cell-to-cell adherens junctions. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19(10):2286–2297. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.10.2286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blum R, Stephens DJ, Schulz I. Lumenal targeted GFP, used as a marker of soluble cargo, visualises rapid ERGIC to Golgi traffic by a tubulo-vesicular network. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 18):3151–3159. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.18.3151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knipe L, Meli A, Hewlett L, et al. A revised model for the secretion of tPA and cytokines from cultured endothelial cells. Blood. 2010;116(12):2183–2191. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-276170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohno H, Tomemori T, Nakatsu F, et al. μ1B, a novel adaptor medium chain expressed in polarized epithelial cells. FEBS Lett. 1999;449(2-3):215–220. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00432-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonnemaison M, Bäck N, Lin Y, Bonifacino JS, Mains R, Eipper B. AP-1A controls secretory granule biogenesis and trafficking of membrane secretory granule proteins. Traffic. 2014;15(10):1099–1121. doi: 10.1111/tra.12194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bonnemaison ML, Bäck N, Duffy ME, et al. Adaptor Protein-1 Complex Affects the Endocytic Trafficking and Function of Peptidylglycine α-Amidating Monooxygenase, a Luminal Cuproenzyme. J Biol Chem. 2015 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.641027. jbc.M115.641027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferraro F, Kriston-Vizi J, Metcalf DJ, et al. A two-tier Golgi-based control of organelle size underpins the functional plasticity of endothelial cells. Dev Cell. 2014;29(3):292–304. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richardson M, Tinlin S, De Reske M, Webster S, Senis Y, Giles AR. Morphological alterations in endothelial cells associated with the release of von Willebrand factor after thrombin generation in vivo. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994;14(6):990–999. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.6.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dong JF, Moake JL, Nolasco L, et al. ADAMTS-13 rapidly cleaves newly secreted ultralarge von Willebrand factor multimers on the endothelial surface under flowing conditions. Blood. 2002;100(12):4033–4039. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shang D, Zheng XW, Niiya M, Zheng XL. Apical sorting of ADAMTS13 in vascular endothelial cells and Madin-Darby canine kidney cells depends on the CUB domains and their association with lipid rafts. Blood. 2006;108(7):2207–2215. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-002139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bernardo A, Ball C, Nolasco L, Moake JF, Dong JF. Effects of inflammatory cytokines on the release and cleavage of the endothelial cell-derived ultralarge von Willebrand factor multimers under flow. Blood. 2004;104(1):100–106. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang J, Roth R, Heuser JE, Sadler JE. Integrin α(v)β(3) on human endothelial cells binds von Willebrand factor strings under fluid shear stress. Blood. 2009;113(7):1589–1597. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-158584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Springer TA. von Willebrand factor, Jedi knight of the bloodstream. Blood. 2014;124(9):1412–1425. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-378638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paczkowski JE, Richardson BC, Fromme JC. Cargo adaptors: structures illuminate mechanisms regulating vesicle biogenesis. Trends Cell Biol. 2015;25(7):408–416. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hannah MJ, Williams R, Kaur J, Hewlett LJ, Cutler DF. Biogenesis of Weibel-Palade bodies. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2002;13(4):313–324. doi: 10.1016/s1084-9521(02)00061-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Savage B, Sixma JJ, Ruggeri ZM. Functional self-association of von Willebrand factor during platelet adhesion under flow. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(1):425–430. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012459599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barg A, Ossig R, Goerge T, et al. Soluble plasma-derived von Willebrand factor assembles to a haemostatically active filamentous network. Thromb Haemost. 2007;97(4):514–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sakariassen KS, Bolhuis PA, Sixma JJ. Human blood platelet adhesion to artery subendothelium is mediated by factor VIII-Von Willebrand factor bound to the subendothelium. Nature. 1979;279(5714):636–638. doi: 10.1038/279636a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]