Abstract

Background

This paper presents the first quantitative ethnobotanical study of the flora in Toli Peer National Park of Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan. Being a remote area, there is a strong dependence by local people on ethnobotanical practices. Thus, we attempted to record the folk uses of the native plants of the area with a view to acknowledging and documenting the ethnobotanical knowledge. The aims of the study were to compile an inventory of the medicinal plants in the study area and to record the methods by which herbal drugs were prepared and administered.

Materials and methods

Information on the therapeutic properties of medicinal plants was collected from 64 local inhabitants and herbalists using open ended and semi-structured questionnaires over the period Aug 2013-Jul 2014. The data were recorded into a synoptic table comprising an ethnobotanical inventory of plants, the parts used, therapeutic indications and modes of application or administration. Different ethnobotanical indices i.e. relative frequencies of citation (RFC), relative importance (RI), use value (UV) and informant consensus factor (Fic), were calculated for each of the recorded medicinal plants. In addition, a correlation analysis was performed using SPSS ver. 16 to check the level of association between use value and relative frequency of citation.

Results

A total of 121 species of medicinal plants belonging to 57 families and 98 genera were recorded. The study area was dominated by herbaceous species (48%) with leaves (41%) as the most exploited plant part. The Lamiaceae and Rosaceae (9% each) were the dominant families in the study area. Among different methods of preparation, the most frequently used method was decoction (26 species) of different plant parts followed by use as juice and powder (24 species each), paste (22 species), chewing (16 species), extract (11 species), infusion (10 species) and poultice (8 species). The maximum Informant consensus factor (Fic) value was for gastro-intestinal, parasitic and hepatobiliary complaints (0.90). Berberis lycium Ajuga bracteosa, Prunella vulgaris, Adiantum capillus-veneris, Desmodium polycarpum, Pinus roxburgii, Albizia lebbeck, Cedrella serrata, Rosa brunonii, Punica granatum, Jasminum mesnyi and Zanthoxylum armatum were the most valuable plants with the highest UV, RFC and relative importance values. The Pearson correlation coefficient between UV and RFC (0.881) reflects a significant positive correlation between the use value and relative frequency of citation. The coefficient of determination indicated that 77% of the variability in UV could be explained in terms of RFC.

Conclusion

Systematic documentation of the medicinal plants in the Toli Peer National Park shows that the area is rich in plants with ethnomedicinal value and that the inhabitants of the area have significant knowledge about the use of such plants with herbal drugs commonly used to cure infirmities. The results of this study indicate that carrying out subsequent pharmacological and phytochemical investigations in this part of Pakistan could lead to new drug discoveries.

Introduction

Ethnobotany describes the complete relationship between people and plants and explores both the traditional botanical knowledge of local people and how they exploit plants for a variety of purposes [1–2]. Ethnobotanical studies emphasize the dynamic relationships between botanical diversity and social and cultural systems [3–4] and ethnobotanists are increasingly focusing on the application of different quantitative and statistical approaches to understand and accumulate knowledge on valuable plants in certain communities [5].

Medicinal knowledge about plants is receiving increasing attention and is recognized as a valuable asset worldwide for health care practices and as a driver of the conservation of medicinal plants [6]. For example, ethnobotany and ethno-pharmacological knowledge is considered to be an integral part of the knowledge required for drug development. ‘Ethnomedicine’ deals with cultural interpretations of health, disease and illness with a focus on different healing practices or processes concerned with gaining good health [7]. Based on traditional reports about the use and efficacy of plant-derived medicines, various plants are being screened in order to search for their active ingredients which may be employed in the development of novel drugs. According to the FAO, in the last few decades the number of known medicinal plants now reaches up to 50,000 different species which is 18.9% of the total world flora [8]. Despite the fact that traditional ethnomedicinal approaches may be considered to be outdated in comparison with modern westernised approaches to health care, the WHO report estimates that about 80% of the population in developing countries depend upon herbal medicines for curing aliments [9].

In Pakistan, the remote mountainous regions support a diversity of flora, with about 1572 plant genera and 5521 species [10]. In the mid-1990s, about 84% of the Pakistani population was reliant on herbal medication but now this traditional knowledge is confined only to remote areas of the country, particularly the mountainous regions. As indigenous knowledge is dynamic and changes with time, generation, culture and resources the accurate documentation of this knowledge is both timely and necessary [11]. The indigenous knowledge about medicinal plants among indigenous communities has been reported from various parts of the world [12–17] including Pakistan [18–27]. However, all these studies adapted qualitative approaches to document ethnobotanical information [28–29], while the use of quantitative approaches can lead to better interpretation of ethnobotanical data.

Azad Jammu and Kashmir is a lush mountainous area characterized by its diverse climate, soil and habitat types. A number of endemic medicinal plants of Pakistan are restricted to this area, while previous studies in different parts of Azad Jammu and Kashmir have revealed that the people possess a unique culture and have rich traditional knowledge [1, 30–32]. Toli Peer National Park supports some of the richest biodiversity in Kashmir. Most of the population in this area is rural with a low literacy rate. People lack modern health facilities and hence are dependent upon natural resources, especially plants, for healthcare and to compensate for low incomes. However, ethno-pharmacological studies specifically targeting the Toli Peer National Park are lacking, as is the validation of traditional uses of this area’s native plant species. This may be because the area is topographically challenging, comprising hills and steep slopes which make it difficult to access for research studies. In order to address this information gap, we undertook the present study with the aims of (i) compiling a complete inventory of the flora of the study area, and (ii) documenting the indigenous medicinal knowledge of these plants along with their methods of preparation and the folk recipes used by local herbalists. In addition, we also undertook various quantitative analyses in order to produce and compare relevant ethnobotanical indices in order to explore relationships between plant frequency of occurrence and ethnomedicinal use.

Materials and methods

Study area (climate, geo-ethnography and socio-economic conditions)

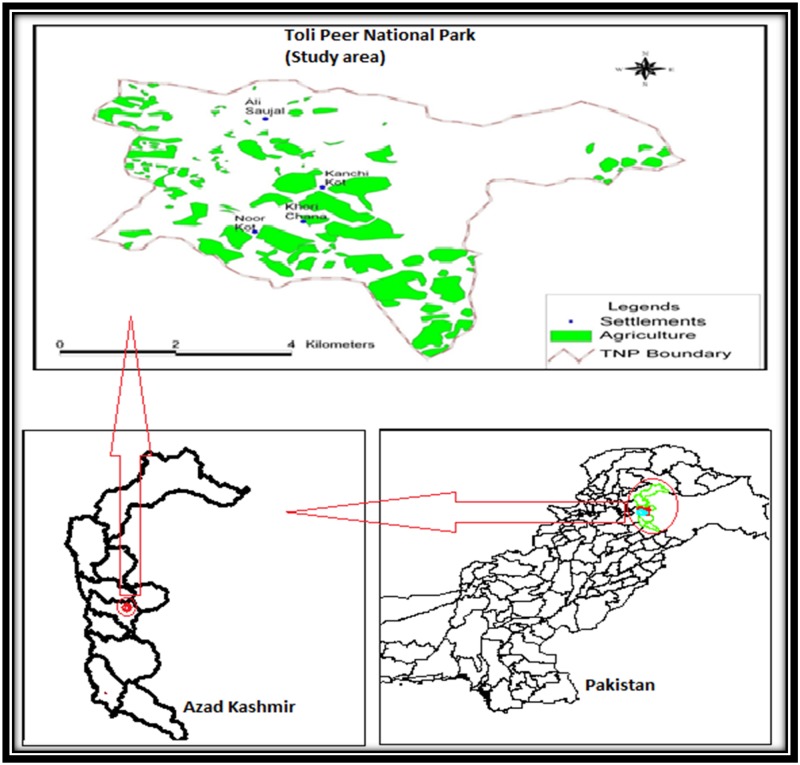

Toli Peer National Park is located in one of the world’s biodiversity hotspots. It is a mountainous area in Tehsil Rawalakot, District Poonch of Azad Kashmir, Pakistan. It lies at an altitude of 2546 m, with latitude 33.89°N and longitude 73.91°E. The climate of this region is of the moist temperate type. The maximum rainfall recorded is 1018 mm while the minimum is 3 mm during the summer monsoon in August and in October respectively. The average lowest temperatures are recorded in January (11C°) with temperature rising to maxima in June (average 34C°) [33–34]. There is heavy snow between November and March especially at higher elevations. The vegetation in the area comprises a wide variety of trees, shrubs, herbs, grasses and climbers with ground cover comprising a diversity of angiosperms along with ferns and mosses [33–34]. (A map of the study area is given in Fig 1).

Fig 1. Map showing location of Toli Peer National Park within Pakistan and Azad Kashmir.

A high proportion of the indigenous people of this hilly district are nomads. During the early summer months, they move their livestock herds from the plains to the higher mountainous areas of the National Park, and stay there for the whole of the summer season. Prior to the onset of winter, they make their way back down to the plains. A number of the main occupations are associated with summer tourism, including rest house managers, tour guides, shop keepers, restaurant workers and jeep drivers. However, many are full or part-time farmers and shepherds.

There is no formal marketing of medicinal plant in Toli Peer which by implication benefits home grown agents (middle man). Thus poor collectors have no share in high profit earning business. The study area was badly affected by an earthquake in 2005 which had a negative socioeconomic impact on the local population, including a rapid decline in the population sizes of some of the villages inside the National Park. The region is characterized by its remoteness, long distance from urban centers, difficult mountainous terrain, and a lack of government services, including modern health care facilities. As a result there is relatively high percentage of deaths among the more elderly members of the population as well as migration of many of the younger people away from the area to other safer and better developed centers. In the light of these demographic changes, it is vital to document the local knowledge of medicinal plant usage in this area before such information declines or is lost completely.

Data collection

Field trips were conducted during Aug 2014-Jul 2015 in four seasons following the method of Heinrich and coworker [35]. During the study, 64 informants were selected randomly via convenience sampling of which 39 were males and 25 females. For the collection of ethnobotanical data, a semi-structured questionnaire was used to undertake one-on-one interviews in addition to group discussions [36–37] with some key informants as reported by Ghorbani et al. [19] The questionnaire was developed following the method of Edwards et al. [38] and required the informants to provide information regarding the local names of the medicinal plants, the diseases treated by herbal remedies, the plant parts used, the methods of preparation and the mode of administration. These discussions comprised both mixed as well as single gender discussions and were conducted in the local language, Pharari (Pothohari). The age of the informants ranged from 35 to 70 years. They included several Hakeems (traditional doctors) who were interviewed in order to record the local household recipes for the preparation of medicinal plants. Detailed demographic data are provided in Table 1. The informed consent from participants is also obtained to participate in this research before obtaining information. The permission for conducting research, field surveys and plant collection in Toli Peer national park was taken from chief conservator forest Department, Azad Jammu & Kashmir, Pakistan.

Table 1. Demographic data of informants in Toli Peer National park.

| Variable | Categories | No. of Persons | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Informant category | Traditional healer | 11 | 17.19 |

| Indigenous people | 58 | 90.63 | |

| Gender | Female | 25 | 39.06 |

| Male | 39 | 60.94 | |

| Age | 35–50 years | 23 | 35.94 |

| 50–65 years | 28 | 43.75 | |

| More than 65 years | 18 | 28.13 | |

| Education Level | Illiterate | 21 | 32.81 |

| Completed five years of education | 16 | 25.00 | |

| Completed eight years of education | 11 | 17.19 | |

| Completed 10 years of education | 8 | 12.50 | |

| Completed 12 years of education | 7 | 10.94 | |

| Some undergraduate (16 year education) | 4 | 6.25 | |

| Graduate (Higher education) | 2 | 3.13 | |

| Experience of the traditional health practitioners | Less than 2 years | 2 | 18.18 |

| 2–5 years | 4 | 36.36 | |

| 5–10 years | 3 | 27.27 | |

| More than 20 years | 2 | 18.18 |

Collection and identification of plants

Those plants in the study area that were identified as having a medicinal value were collected, pressed until dry, sprayed with a preservative 1% HgCl2 solution and mounted on to herbarium sheets. Voucher specimens were gathered and prepared according to standard taxonomic methods recommended by Jain and Rao [39]. For taxonomic identification, the Flora of Pakistan (www.eflora.com) was followed [40–41], whereas the International Plant Name Index (IPNI) (www.ipni.org) was used to obtain botanical names. The confirmation of identified plant was done in the Herbarium of Pakistan (ISL) Quaid—i–Azam University Islamabad, Pakistan. The fully determined vouchers were deposited in the herbarium of the Department of Botany, PMAS- Arid Agriculture University Rawalpindi, Pakistan.

Quantitative ethnobotanical data analysis

For the validation and to test the homogeneity of the collected ethnobotanical data various quantitative indices were applied including use value (UV), relative frequency of citation (RFC), the informant consensus factor (Fic), and relative importance (RI). Association between indices was tested using correlation analysis.

Informant consensus factor (Fic)

The informant consensus factor was derived in order to seek an agreement between the informants on the reported cures for each group of diseases [42].

Where Nur is the number of use-reports in each disease category; Nt is number of species used.

Relative frequency of citation (RFC)

The index of relative frequency of citation (RFC) was determined by using the following formula [43]

Where FC is the number of informants reporting use of a particular species and N is the total number of informants.

Use value index

The use value was calculated by using the following formula [43].

where Ui is the number of uses mentioned by each informant for a given species and N is the total number of informants.

Relative importance

The relative importance was calculated by applying the following formula [44].

where PH is the pharmacological property of the given plant and Rel PH is the relative number of pharmacological properties ascribed to a single plant.

BS is the number of body systems treated by a single species and Rel BS is the relative number of body systems treated by a single species

Jaccard index (JI)

To compare the study with already published work and to access similarity of knowledge among different communities, the Jaccard index [45] was calculated using the following formula

Where “a” is the number of species of the area A (our study area); “b” is the number of species of the neighboring area B; and “c” is the number of species common to both A and B.

Pearson correlation

Pearson Correlation analysis was carried out between the RFC and UV using SPSS ver. 16, the r2 was also calculated to measure cross species variability in RFC explained by variance in UV.

Results and discussion

Family contribution and habit of ethnomedicinal flora

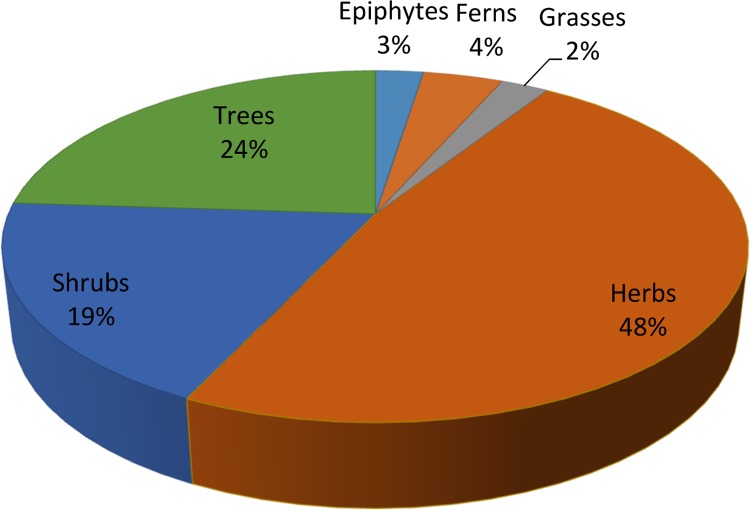

Altogether 121 medicinal plant species belonging to 98 genera and 57 families are reported (Table 2). Lamiaceae and Rosaceae (11 species each) are the dominant families of the study area followed by Asteraceae (10 species), Papilionaceae (6 species) and Ranunculaceae (6 species). The remaining families contribute ≤5 species in the ethnomedicinal flora of the study area. The dominance of these families is attributed to the fact that they are abundant in the area and easily available to the local people. In addition, people of the area have a high knowledge about plants from these families, i.e. they have been using these plants for many generations and hence the members of these plant families are well known to them. This is probably due to the presence of secondary metabolites in important plant species of these families. A similar report was presented earlier by [46] where Lamiaceae, Moraceae, Astraceae, Mimosaceae, Apocyanaceae and Liliaceae were documented as dominant ethnomedicinal plant families among a total of 25 families from Darra Adam Khel NWFP, Pakistan. The majority of the medicinal plant species identified in the study area are reportedly utilized to treat respiratory disorders, followed by gastrointestinal and other complaints (Tables 3 and 4). This result is also in agreement with previous studies. For example, Abbasi et al. [47] reported 89 ethnomedicinal plant species in 46 families from the Lesser Himalayas of Pakistan with the highest informant consensus factor reported for pathologies related to respiratory and reproductive disorders. Similarly, Kiyani et al. [48] reported use of 120 plant species from 51 plant families that were applied in the treatment of 25 different respiratory problems by the inhabitants of Gallies-Abbottaba in northern Pakistan. There is a particular prevalence of respiratory diseases in the study area due to the high altitude combined with low barometric pressure which limits the supply of oxygen (O2) thereby impacting on lung function [49]. Most of the plant species in the area identified as having an ethnomedicinal value were herbaceous (58%), followed by trees (29%), shrubs (23%), ferns (5%), grasses (3%) and climbers (3%) (Fig 2). These results reflect the high altitude of the study area where the herbaceous flora is dominant with fewer shrubs and trees.

Table 2. Distribution of medicinal plant species according to their family.

| Family | No. of Species | %age contribution | Family | No. of Species | %age contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lamiaceae | 11 | 9.09 | Borangniceae | 1 | 0.83 |

| Rosaceae | 11 | 9.09 | Buxaceae | 1 | 0.83 |

| Asterceae | 10 | 8.26 | Companulaceae | 1 | 0.83 |

| Paplionaceae | 6 | 4.96 | Cucurbitaceae | 1 | 0.83 |

| Ranunculaceae | 6 | 4.96 | Dryopteridaceae | 1 | 0.83 |

| Fragaceae | 5 | 4.13 | Fumaricaceae | 1 | 0.83 |

| Adiantaceae | 3 | 2.48 | Gentianaceae | 1 | 0.83 |

| Apiaceae | 3 | 2.48 | Guttiferae | 1 | 0.83 |

| Caprifoliaceae | 3 | 2.48 | Hippocotanaceae | 1 | 0.83 |

| Pinaceae | 3 | 2.48 | Juglandaceae | 1 | 0.83 |

| Poaceae | 3 | 2.48 | Malvaceae | 1 | 0.83 |

| Dioscoreaceae | 2 | 1.65 | Melliaceae | 1 | 0.83 |

| Elaeagnaceae | 2 | 1.65 | Mimoaceae | 1 | 0.83 |

| Euphorbiaceae | 2 | 1.65 | Myrsinaceae | 1 | 0.83 |

| Liliaceae | 2 | 1.65 | Onagraceae | 1 | 0.83 |

| Moraceae | 2 | 1.65 | Plantaginaceae | 1 | 0.83 |

| Oleaceae | 2 | 1.65 | Podophyllaceae | 1 | 0.83 |

| Polygonoceae | 2 | 1.65 | Primulaceae | 1 | 0.83 |

| Rubicaceae | 2 | 1.65 | Pteridaceae | 1 | 0.83 |

| Rutaceae | 2 | 1.65 | Punicacea | 1 | 0.83 |

| Salicaceae | 2 | 1.65 | Rhamnaceae | 1 | 0.83 |

| Violaceae | 2 | 1.65 | Sambucaceae | 1 | 0.83 |

| Acanthaceae | 1 | 0.83 | Sapindaceae | 1 | 0.83 |

| Alliaceae | 1 | 0.83 | Saxifragaceae | 1 | 0.83 |

| Anacardiaceae | 1 | 0.83 | Smilicaceae | 1 | 0.83 |

| Apocynaceae | 1 | 0.83 | Ulmaceae | 1 | 0.83 |

| Araliaceae | 1 | 0.83 | Urticaceae | 1 | 0.83 |

| Asclepidaceae | 1 | 0.83 | Valerianaceae | 1 | 0.83 |

| Berberidaceae | 1 | 0.83 |

Table 3. Medicinal flora of Toli Peer National Park, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan.

| S# | Binomial /Voucher number | Local name | Habit | Part used | Method of preparation/property | Mode of application | Disease treated | Rel BS | Rel PH | RI | FC | RFC | UV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthaceae | |||||||||||||

| 1 | Dicliptera bupleuroides Nees in Wall./mh-03 | Kirch, somni, herb | Herb | Leaves | Paste | External | Wounds, eczema. | 0.29 | 0.5 | 39.29 | 52 | 0.81 | 0.86 |

| Leaves | Decoction | External | Tonic, cough. | ||||||||||

| Adiantaceae | |||||||||||||

| 2 | Adiantum capillus-veneris L./mh-04 | Hansraj, Sraj fern | Fern | Leaves | Decoction | Internal | Boils, cough, asthma, jaundice, cold, diabetes, skin diseases, measles, eczema, chest pain | 0.71 | 0.83 | 77.38 | 57 | 0.89 | 0.97 |

| 3 | Adiantum incisum Foressk/mh-06 | Sumbul, Hansraj fern | Fern | Leaves | Juice | Internal | Scabies, cough, fever, skin diseases | 0.29 | 0.5 | 39.29 | 44 | 0.69 | 0.64 |

| 4 | Athyrium tenuifrons Wall.apud Moore ex. R. Sim./mh– 07 | Fern | Fern | Root | Tea | Internal | Body pain | 0.14 | 0.33 | 23.81 | 32 | 0.5 | 0.58 |

| Root | Powder | External | Wounds | ||||||||||

| Alliaceae | |||||||||||||

| 5 | Allium griffithianum Boiss./mh– 09 | Piazi | Herb | Aerial parts | Cooked | Internal | Carminative, used in dyspepsia, flatulance and colic | 0.29 | 0.17 | 22.62 | 29 | 0.45 | 0.53 |

| Anacardiaceae | |||||||||||||

| 6 | Pistacia chinensis Bunge/mh -11 | Kangar | Tree | Stem gum | Powder | Internal | Dysentery | 0.21 | 0.33 | 27.38 | 43 | 0.67 | 0.91 |

| Bark | Paste | External | Wounds, cracked heels | ||||||||||

| 7 | Heracleum candicans Wall ex. DC/mh -12 | ---- | Herb | Aerial parts | Tea | Internal | Nerve disorders | 0.07 | 0.17 | 11.9 | 12 | 0.19 | 0.14 |

| 8 | Pimpinella stewartii Dunn. E. Nasir/mh-13 | Tarpakki | Herb | Fruit | Eaten | Internal | Stomach disorder | 0.07 | 0.17 | 11.9 | 12 | 0.19 | 0.3 |

| Apiaceae | |||||||||||||

| 9 | Heracleum cachemirica C.B. Clarke/mh -14 | Shrub | Shrub | Aerial parts | Juice | Internal | Nerve disorders | 0.07 | 0.17 | 11.9 | 18 | 0.28 | 0.19 |

| Apocyanaceae | |||||||||||||

| 10 | Nerium oleander Linn./mh -15 | Kanair | Tree | Leave | Paste | External | Cutaneous eruption | 0.57 | 0.67 | 61.9 | 46 | 0.72 | 0.98 |

| Leave | Decoction | Internal | Wounds and swelling | ||||||||||

| Bark | Decoction | Internal | Skin diseases, leprosy | ||||||||||

| Roots | Powder | Internal | Abortion | ||||||||||

| Roots | Paste | External | Scorpion sting, snake bite | ||||||||||

| Araliaceae | |||||||||||||

| 11 | Hedera nepalensis K. Koch/mh -16 | Harbumbal epiphyte | Epiphyte | Leaves | Decoction | Internal | Diabetes | 0.07 | 0.17 | 11.9 | 11 | 0.17 | 0.13 |

| Asclepidaceae | |||||||||||||

| 12 | Vincetoxicum hirundinaria Medicres/mh-17 | ---- | Herb | Aerial parts | Decoction | Internal | Boils, pimples | 0.14 | 0.17 | 15.48 | 48 | 0.75 | 0.8 |

| Asteraceae | |||||||||||||

| 13 | Anaphalis adnata D.C/mh-18 | ---- | Herb | Leaves | Powder | External | Bleeding cuts and wounds | 0.14 | 0.17 | 15.48 | 19 | 0.3 | 0.42 |

| 14 | Artemisia absinthium L./mh -19 | Afsanthene | Herb | Leaves | Infusion, paste | Internal | Anthelmintic, stomach disorders, wounds and cuts | 0.29 | 0.5 | 39.29 | 51 | 0.8 | 0.98 |

| 15 | Artemisia maritime L./mh -21 | Afsanthene | Herb | Leaves | Paste | External | Skin infections | 0.14 | 0.33 | 23.81 | 41 | 0.64 | 0.77 |

| Leaf and stem | Powder | Internal | Intestinal parasites | ||||||||||

| 16 | Artemisia dubia Wall./mh-22 | Asfanthene | Herb | Seeds | Cooked | Internal | Weakness after delivery | 0.36 | 0.67 | 51.19 | 23 | 0.36 | 0.52 |

| Leaves | Paste | External | Cuts and wounds, ear diseases | ||||||||||

| Aerial parts | Extract | External | Vermicide | ||||||||||

| 17 | Conyza bonariensis L Cronquist/mh-24 | Buti | Herb | Aerial parts | Infusion | Internal | Diarrhea and dysentery, bleeding piles | 0.21 | 0.17 | 19.05 | 41 | 0.64 | 0.77 |

| 18 | Gerbera gossypina (Royle) Beauverd/mh-25 | Put potula | Herb | Aerial parts | Tea | Internal | Nerve disorders | 0.07 | 0.17 | 11.9 | 12 | 0.19 | 0.14 |

| 19 | Parthenium hysterophorus L./mh-27 | Herb | Herb | Root | Decoction | Internal | Skin disorders, dysentery | 0.14 | 0.33 | 23.81 | 35 | 0.55 | 0.59 |

| 20 | Saussurea candolleana Wall. Ex. D.C Clarke/mh-29 | Herb | Herb | Roots | Extract | Internal | Tonic | 0.07 | 0.17 | 11.9 | 23 | 0.36 | 0.28 |

| 21 | Taraxacum officinale F. H. Wigg/mh-31 | Handh | Herb | Roots | Decoction | Internal | Jaundice | 0.29 | 0.67 | 47.62 | 56 | 0.88 | 0.92 |

| Leaves | Cooked | Internal | Swellings, diuretic, tonic | ||||||||||

| 22 | Achillea millefolium L./mh-32 | Yarrow | Herb | Flower | Extract | Internal | Soft drinks | 0.14 | 0.33 | 23.81 | 24 | 0.38 | 0.33 |

| Leaves | Powder | External | Toothache | ||||||||||

| 23 | Berberis lycium Royl/mh-33 | Sumblu | Shrub | Roots | Extract | Internal | Tonic, eye lotion, skin disease, chronic diarrhea, piles, blood purifier, diabetes, pustules, scabies | 0.64 | 1.33 | 98.81 | 59 | 0.92 | 0.98 |

| Roots | Paste | External | Bone fracture | ||||||||||

| Boraginaceae | |||||||||||||

| 24 | Trichodesma indicum L. R. Br/mh-35 | Handusi booti | Herb | Leaves | Boiling | Internal | Flu and cough | 0.14 | 0.17 | 15.48 | 31 | 0.48 | 0.48 |

| Buxaceae | |||||||||||||

| 25 | Sarcococca saligna D. Don Muell/mh-37 | Bansathra | Shrub | Leaves and shoots | Decoction | Internal | Joint pain, laxative, blood purifier | 0.36 | 0.83 | 59.52 | 23 | 0.36 | 0.23 |

| Leaves | Powder | External | Burns | ||||||||||

| Root | Juice | Internal | Gonorrhoea | ||||||||||

| Caprifoliaceae | |||||||||||||

| 26 | Vibernum nervosum D. Don/mh-39 | Taliana | Shrub | Fruit | Eaten | Internal | Stomach ache, anemia | 0.14 | 0.33 | 23.81 | 15 | 0.23 | 0.3 |

| 27 | Viburnum grandiflorum Wall.ex DC/mh-40 | Guch, shrub | Shrub | Seed | Juice | Internal | Typhoid, whooping cough | 0.14 | 0.33 | 23.81 | 25 | 0.39 | 0.2 |

| 28 | Viburnum cotinifolium D. Don/mh-41 | Taliana | Shrub | Fruit | Eaten | Internal | Laxative, blood purifier | 0.21 | 0.5 | 35.71 | 31 | 0.48 | 0.33 |

| Leaves | Extract | Internal | Menorrhagia | ||||||||||

| Companulaceae | |||||||||||||

| 29 | Campanula benthamii Wall./mh-42 | Herb | Herb | Root | Chewing, earache | External | Strengthen heart, earache | 0.14 | 0.33 | 23.81 | 19 | 0.3 | 0.36 |

| Cucurbitaceae | |||||||||||||

| 30 | Momordica dioica Roxb. ex Willd/mh-43 | Epiphyte | Epiphyte | Roots | Cooked | Internal | Piles, urinary problem | 0.14 | 0.33 | 23.81 | 15 | 0.23 | 0.17 |

| Dioscoreaceae | |||||||||||||

| 31 | Dioscorea bulbifera L./mh-45 | Herb | Herb | Aerial parts | Juice | Internal | Contraceptive | 0.07 | 0.17 | 11.9 | 41 | 0.64 | 0.81 |

| 32 | Dioscorea deltoidea Wall. ex Kunth/mh-47 | Herb | Herb | Rhizome | Eaten | Internal | Insect killer, snake bite | 0.14 | 0.33 | 23.81 | 36 | 0.56 | 0.48 |

| Dryopteridaceae | |||||||||||||

| 33 | Polystichum squarrosum Don Fee/mh-49 | Fern | Fern | Root | Decoction | Internal | Pyloric disease | 0.07 | 0.17 | 11.9 | 13 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| Elaeagnaceae | |||||||||||||

| 34 | Elaeagnus angustifolia Linn./mh-50 | Ripe fruits | Boiled | Internal | Sore throat, high fever | 0.29 | 0.5 | 39.29 | 29 | 0.45 | 0.66 | ||

| Fruit | Eaten | Internal | Cough and cold | ||||||||||

| 35 | Elaeagnus umbellata Thunb./mh-51 | Russian olive, Tree | Leaves | Decoction | Internal | Cough | 0.29 | 0.67 | 47.62 | 33 | 0.52 | 0.73 | |

| Flowers | Decoction | Internal | Heart disease | ||||||||||

| Seeds | Eaten | Internal | Immunity | ||||||||||

| Branch | Exude | External | Toothache | ||||||||||

| Euphorbiaceae | |||||||||||||

| 36 | Euphorbia helioscopia Linn./mh-53 | Dhodhal, dandlion | Herb | Seeds | Juice | Internal | Cholera | 0.14 | 0.17 | 15.48 | 49 | 0.77 | 0.72 |

| Roots | Paste | Internal | Anthelmintic | ||||||||||

| 37 | Euphorbia wallichii Hk. f./mh-54 | Dhodhal dandlion | Herb | Aerial parts | Latex | Internal | Laxative, purgative, digestive | 0.36 | 0.33 | 34.52 | 42 | 0.66 | 0.91 |

| Aerial parts | Juice | Internal | Warts, skin infections | ||||||||||

| Fagaceae | |||||||||||||

| 38 | Castanea sativa Mill./mh-56 | Chest nut | Tree | Leaves | Infusion | Internal | Fevers | 0.14 | 0.33 | 23.81 | 21 | 0.33 | 0.38 |

| Leaves | Decoction | Internal | Sore throats | ||||||||||

| Fabaceae | |||||||||||||

| 39 | Dalbergia sissoo Roxb./mh-57 | Tahli | Tree | Stem bark | Juice | External | Skin allergy | 0.21 | 0.5 | 35.71 | 39 | 0.61 | 0.77 |

| Crushed leaves | Juice | Internal | Blood purifier | ||||||||||

| Leaves | Washing | External | Increase hair length | ||||||||||

| Fragaceae | |||||||||||||

| 40 | Quercus baloot Griff/mh-59 | Rein, Shah baloot, Oak | Tree | Bark | Powder | Internal | Asthma | 0.29 | 0.33 | 30.95 | 43 | 0.67 | 0.86 |

| Nut | Decoction | Internal | Urinary problems, cough, cold | ||||||||||

| 41 | Quercus dilatata Royle/mh-62 | Oak, barungi | Tree | Fruit | Powder | Internal | Tonic | 0.14 | 0.33 | 23.81 | 47 | 0.73 | 0.36 |

| Bark | Decoction | Internal | Dysentery | ||||||||||

| 42 | Quercus incana Roxb./mh-64 | Rein, ban, rinji | Tree | Bark | Powder | Internal | Asthma, cough, fever, rheumatism and backache | 0.36 | 0.5 | 42.86 | 41 | 0.64 | 0.95 |

| Fumaricaceae | |||||||||||||

| 43 | Fumaria indica (Hausskan) Pugsley/mh-66 | Papra | Herb | Aerial parts | Juice, paste | Internal | Fever, constipation, pimples, eruption, skin infections, purify blood | 0.43 | 0.67 | 54.76 | 48 | 0.75 | 0.84 |

| Gentianaceae | |||||||||||||

| 44 | Swertia ciliate G. Don B. L. Burtt/mh-67 | Herb | Herb | Aerial part | Decoction | Internal | Cough cold and fever | 0.21 | 0.33 | 27.38 | 48 | 0.75 | 0.88 |

| Guttiferae | |||||||||||||

| 45 | Hypericum perforatum L./mh-68 | Herb | Herb | Flowers | Infusion | Internal | Snake bite wounds, sores, swellings, ulcers, rheumatism | 0.36 | 0.5 | 42.86 | 47 | 0.73 | 0.61 |

| Hippocotanaceae | |||||||||||||

| 46 | Aesculus indica (Wall. Ex Camb.) Hook.f.)/mh-69 | Bankhore, horsechestnut | Tree | Bark | Infusion | Internal | Tonic | 0.29 | 0.67 | 47.62 | 33 | 0.52 | 0.5 |

| Fruits | Eaten | Internal | Colic, rheumatic pains | ||||||||||

| Seed | Powder | Internal | Leucorrhoea | ||||||||||

| Juglandaceae | |||||||||||||

| 47 | Juglans regia L./mh-70 | Akhrot, khore | Tree | Leave | Decoction | External | Antispasmodic | 0.36 | 0.67 | 51.19 | 51 | 0.8 | 0.92 |

| Bark | Rubbing | External | Gums and cleaning teeth, make lips and gums dye | ||||||||||

| Seeds | Oil | External | Rheumatic pain | ||||||||||

| Roots and leaves | Powder | External | Antiseptic | ||||||||||

| Lamiaceae | |||||||||||||

| 48 | Isodon rugosus Wall. ex Benth. Codd./mh-72 | Khwangere | Shrub | Leaves | Decoction | Internal | Blood pressure, toothache, body temperature, rheumatism | 0.29 | 0.67 | 47.62 | 37 | 0.58 | 0.75 |

| 49 | Ajuga bracteosa Wall, ex Benth/mh-73 | Ratti booti | Herb | Aerial parts | Extract | Internal | Blood purification, body inflammation, eruption, pimples | 0.64 | 1 | 82.14 | 58 | 0.91 | 1 |

| Leaves | Extract | Internal | Earache, eye ache, boils, mouth gums, throat pain | ||||||||||

| 50 | Nepeta erecta Royle ex. Benth Benth/mh-75 | Herb | Herb | Flowers | Juice | Internal | Cough | 0.43 | 0.67 | 54.76 | 53 | 0.83 | 0.78 |

| Leaves | Juice | Internal | Blood pressure, cold, fever, influenza, toothache | ||||||||||

| 51 | Nepeta laevigata D. Don Hand/mh-77 | Herb | Herb | Fruit | Infusion | Internal | Dysentery | 0.07 | 0.17 | 11.9 | 17 | 0.27 | 0.22 |

| 52 | Mentha royleana subsp. hymalaiensis Briq./mh-79 | Podina | Herb | Leaves | Juice, Powder to make chattni | Internal | Stomach disorder, gas trouble, indigestion, vomiting, cholera, fever and cough | 0.5 | 0.5 | 50 | 58 | 0.91 | 0.97 |

| 53 | Prunella vulgaris L./mh-81 | Herb | Herb | Seeds | Eaten | Internal | Laxative, antipyretic, tonic, diuretic, inflammation, heart disease difficult breathing, eye sight weakness | 0.57 | 1 | 78.57 | 58 | 0.91 | 0.98 |

| 54 | Salvia hians Royle/mh-82 | Herb | Herb | Leaves | Juice | Internal | Cough, colds, anxiety | 0.21 | 0.33 | 27.38 | 31 | 0.48 | 0.66 |

| 55 | Salvia lanata Roxb./mh-83 | Herb | Herb | Leaves | Poultice | External | Skin problems, wounds | 0.14 | 0.33 | 23.81 | 27 | 0.42 | 0.48 |

| 56 | Salvia moorcroftiana Wall. Ex Benth/mh-84 | Kaljari | Herb | Aerial parts | Juice | Internal | Diarrhea, gas trouble, stomach disorders, cough | 0.29 | 0.33 | 30.95 | 51 | 0.8 | 0.89 |

| 57 | Thymus liniaris Benth. ex Beth./mh/85 | Herb | Herb | Leaves and flowers | Powder | Internal | Strengthen teeth, gum infection, bleeding | 0.29 | 0.5 | 39.29 | 32 | 0.5 | 0.64 |

| Flower | Along ground seeds of Carum carvi | Internal | Improve digestion | ||||||||||

| Liliaceae | |||||||||||||

| 58 | Asparagus filicinus Ham. in D. Don/mh-87 | Herb | Herb | Root | Decoction | Internal | Diuretic, antipyretic, stomachic, nervous stimulant | 0.29 | 0.5 | 39.29 | 38 | 0.59 | 0.66 |

| 59 | Polygonatum multiflorum L. Smith/mh-88 | Herb | Herb | Leave | Paste | External | Wounds | 0.07 | 0.17 | 11.9 | 17 | 0.27 | 0.19 |

| Meliaceae | |||||||||||||

| 60 | Cedrella serrata Royle/mh-89 | Drawa | Tree | Stem and root bark | Paste | External | Round worms | 0.5 | 1 | 75 | 54 | 0.84 | 0.83 |

| Leaves | Juice | Internal | Digestive problems, diabetes | ||||||||||

| Leaves | Decoction | External | Cooling agent, excellent hair washing | ||||||||||

| Bark | Poultice | Internal | Ulcers, | ||||||||||

| Bark | Powder | Internal | Chronic infantile dysentery | ||||||||||

| Mimosaceae | |||||||||||||

| 61 | Albizia lebbeck Linn. (Benth)./mh-90 | Shirin | Tree | Seeds | Powder | External | Inflammation, skin diseases, leprosy, leukoderma | 1 | 0.5 | 75 | 57 | 0.89 | 0.83 |

| Bark | Powder | External | Strengthen spongy gums | ||||||||||

| Bark and seeds | Extract | Internal | Piles, diarrhea and dysentery | ||||||||||

| Flowers | Paste | External | Carbuncles, boils, swelling and other skin diseases | ||||||||||

| Seed | Oil | External | Snake bite, breathing problems | ||||||||||

| Malvaceae | |||||||||||||

| 62 | Malvastrum coromandelianum Linn. (Garcke)/mh-91 | Herb | Herb | Aerial parts | Decoction | Internal | Kill worms, dysentery | 0.14 | 0.33 | 23.81 | 38 | 0.59 | 0.41 |

| Moraceae | |||||||||||||

| 63 | Ficus palmate Forssk./mh-92 | Phaghwar, anjir | Tree | Fruit | Eaten | Internal | Demulcent laxative, diseases of the lungs and the bladder, cooling agent, laxative | 0.43 | 0.5 | 46.43 | 37 | 0.58 | 0.84 |

| Aerial parts | Paste | External | Freckles | ||||||||||

| Latex | External | Skin problem | |||||||||||

| 64 | Ficus carica L/mh-94. | Phagwar | Tree | Fruit | Eaten | Internal | Constipation, piles, urinary bladder problems, anemia, constipation | 0.57 | 0.67 | 61.9 | 52 | 0.81 | 0.95 |

| Leaves | Latex | External | Nail wound. | ||||||||||

| Latex | Rubbing | External | Extract spines from feet or other body organs | ||||||||||

| Myrsinaceae | |||||||||||||

| 65 | Myrsine africana Linn./mh-95 | Gorkhan, chapra, bebrang | Shrub | Fruits | Powder | Internal | Anthelmintic, carminative, stomach tonic, laxative | 0.36 | 0.5 | 42.86 | 49 | 0.77 | 0.84 |

| Leaves | Decoction | Internal | Blood purifier | ||||||||||

| Oleaceae | |||||||||||||

| 66 | Jasminum mesnyi Hance/mh-97 | Pili chambali | Shrub | Leaves | Powder | External | Dandruff, muscular pains | 0.5 | 0.83 | 66.67 | 51 | 0.8 | 0.67 |

| Leaves | Chewing | Internal | Mouth ulcers | ||||||||||

| Leaves | Decoction | Internal | Pyorrhea | ||||||||||

| Branches | Ash | External | Migraine and small joint pain | ||||||||||

| Dried flower | Powder | Internal | Hepatic disorders | ||||||||||

| 67 | Ligustrum lucidum W. T. Aiton/mh-99 | Guliston | Shrub | Aerial parts | Extracts | Internal | Antitumor | 0.07 | 0.17 | 11.9 | 23 | 0.36 | 0.5 |

| Onagraceae | |||||||||||||

| 68 | Oenothera rosea L.Her. ex Ait/mh-100 | Buti | Herb | Leaves | Infusion | Internal | Hepatic pain, kidney disorders | 0.14 | 0.33 | 23.81 | 45 | 0.7 | 0.64 |

| Paplionaceae | |||||||||||||

| 69 | Sophora mollis Royle Baker/mh-101 | Shrub | Shrub | Flowers | Powder | External | Pimples, sun burns, swellings, wounds | 0.29 | 0.5 | 39.29 | 21 | 0.33 | 0.36 |

| 70 | Alysicarpus bupleurifolius L. D.C/mh-102 | Herb | Herb | Leaves | Juice | Internal | Blood purification. | 0.07 | 0.17 | 11.9 | 15 | 0.23 | 0.22 |

| 71 | Melilotus alba Desr/mh-104 | Herb | Herb | Leaves | Paste | External | Joint inflammation | 0.07 | 0.17 | 11.9 | 15 | 0.23 | 0.3 |

| 72 | Robinia pseudo-acacia L./mh-105 | Kikar | Tree | Bark | Chewing | External | Toothache | 0.07 | 0.17 | 11.9 | 31 | 0.48 | 0.8 |

| 73 | Desmodium polycarpum DC./mh-107 | Shrub | Shrub | Roots | Juice | Internal | Fever, cardiac tonic, diuretic, loss of appetite, flatulence, diarrhea, dysentery, nausea, piles, helminthiasis, cough, fever | 0.86 | 0.67 | 76.19 | 34 | 0.53 | 0.88 |

| 74 | Lespedeza juncea Linn.f./mh-108 | Herb | Herb | Root | Juice | Internal | Diarrhorea and dysentery | 0.14 | 0.17 | 15.48 | 26 | 0.41 | 0.38 |

| Pinaceae | |||||||||||||

| 75 | Abies pindrow Royle/mh-109 | Partal, Paluder silver fir | Tree | Leaf | Paste | External | Swelling | 0.57 | 0.67 | 61.9 | 48 | 0.75 | 1.03 |

| Juice | Internal | Fever | |||||||||||

| Bark | Powder | Internal | Cough, Chronic asthma | ||||||||||

| Bark | Tea | Internal | Rheumatism | ||||||||||

| Resin | External | Cuts and wounds | |||||||||||

| Root | Decoction | Internal | Cough, bronchitis | ||||||||||

| 76 | Pinus roxburgii Roxb/mh-111 | Chir | Tree | Leaves bark Powder | Juice | Internal | Dysentery | 0.5 | 1 | 75 | 58 | 0.91 | 1.13 |

| Resin | Poultice | Internal | Ulcer, tumors, bleeding, wounds, severe cough, snake bite | ||||||||||

| 77 | Pinus wallichiana A.B. Jackson/mh-112 | Biar, blue pine | Tree | Resin | Poultice | External | Cuts and wounds | 0.14 | 0.17 | 15.48 | 42 | 0.66 | 0.84 |

| Poaceae | |||||||||||||

| 78 | Desmostachya bipinnata L. Stapf./ mh-115 | Grass | Grass | Roots | Tea | Internal | Hypertension | 0.07 | 0.17 | 11.9 | 14 | 0.22 | 0.17 |

| 79 | Poa nepalensis Walls ex. Duthie./mh-117 | Grass | Grass | Leaves | Decoction mixed with water | External | Anti lice | 0.07 | 0.17 | 11.9 | 29 | 0.45 | 0.42 |

| 80 | Themeda ananthra Nees ex Steud. Anderss./mh-118 | Grass | Grass | Aerial parts | Poultice | External | Lumbago | 0.14 | 0.33 | 23.81 | 41 | 0.64 | 0.5 |

| Leaves | Decoction | Internal | Blood purifier | ||||||||||

| Plantaginaceae | |||||||||||||

| 81 | Plantago lanceolata L./mh-119 | Ispgol | Herb | Leaves | Paste | External | Wounds | 0.36 | 0.5 | 42.86 | 53 | 0.83 | 0.91 |

| Seeds | Extract | Internal | Tooth ache, dysentery, purgative, haemostatic | ||||||||||

| Podophyllaceae | |||||||||||||

| 82 | Podophyllum emodi Wall ex Royle/mh-122 | Banhakri | Herb | Root | Extract | Internal | Purgative, stomach diseases, liver and bile diseases | 0.36 | 0.5 | 42.86 | 48 | 0.75 | 0.83 |

| Polygonoceae | |||||||||||||

| 83 | Rumex hastatus L./mh-124 | Khatimal | Shrub | Roots | Juice | Internal | Asthma, cough, and fever, weakness in cattle | 0.29 | 0.5 | 39.29 | 32 | 0.5 | 0.64 |

| 84 | Rumex dentatus L./mh-125 | Jangli palak | Herb | Leaves | Paste | External | Wounds | 0.14 | 0.33 | 23.81 | 41 | 0.64 | 0.59 |

| Roots | Paste | External | Skin problems | ||||||||||

| Primulaceae | |||||||||||||

| 85 | Androsace rotundifolia Hardwicke/mh-128 | Herb | Herb | Rhizome | Extract | Internal | Ophthalmic diseases | 0.21 | 0.5 | 35.71 | 25 | 0.39 | 0.67 |

| Leaves | Infusion | Internal | Stomach problems, skin diseases | ||||||||||

| Punicacea | |||||||||||||

| 86 | Punica granatum Linn./mh-129 | Druna | Tree | Fruit | Eaten | Internal | Cough, tonic | 0.5 | 0.83 | 66.67 | 52 | 0.81 | 1 |

| Leaves | Juice | Internal | Dysentery | ||||||||||

| Bark stem and root | Decoction | Internal | Anthelmintic, especially for tapeworms, mouthwash, expectorant | ||||||||||

| Pteridaceae | |||||||||||||

| 87 | Pteris cretica L./mh-131 | Fern | Fern | Leaves | Paste | External | Wounds | 0.07 | 0.17 | 11.9 | 9 | 0.14 | 0.17 |

| Ranunculaceae | |||||||||||||

| 88 | Anemone tetrasepala Royle/mh-132 | Herb | Herb | Roots | Juice | External | Boils | 0.07 | 0.17 | 11.9 | 12 | 0.19 | 0.34 |

| 89 | Aquilegia pubiflora Wall ex Royle./mh-133 | Herb | Herb | Root | Paste | External | Snake bite, emetic, toothache | 0.36 | 0.5 | 42.86 | 37 | 0.58 | 0.45 |

| Flower | Paste | External | Skin burns, wound | ||||||||||

| 90 | Caltha alba Camb. var. alba/mh-136 | Herb | Herb | Aerial parts | Juice | Internal | Antispasmodic, sedative | 0.14 | 0.33 | 23.81 | 29 | 0.45 | 0.28 |

| 91 | Clematis buchananiana DC./mh-138 | Langi | Shrub | Leaves | Paste | External | Skin infection, chambal wounds | 0.36 | 0.5 | 42.86 | 43 | 0.67 | 0.75 |

| Roots | Crushing and wrapping | External | Bleeding from nose | ||||||||||

| Roots | Poultice | External | Swellings, inflammation | ||||||||||

| Roots | Juice | Internal | Peptic ulcers | ||||||||||

| 92 | Clematis montana Buch./mh-139 | Langi, shrub | Shrub | Leaves | Extract | Internal | Diabetes | 0.14 | 0.33 | 23.81 | 27 | 0.42 | 0.33 |

| Flowers | Decoction | Internal | Cough | ||||||||||

| 93 | Ranunculus muricatus L./mh-140 | Herb | Herb | Aerial parts | Cooked | Internal | Asthma | 0.07 | 0.17 | 11.9 | 14 | 0.22 | 0.19 |

| Rhamnaceae | |||||||||||||

| 94 | Ziziphus nummularia (Burm.f.) Wight & Arn./mh-141 | Ber | Tree | Fruit | Decoction | External | Dandruff | 0.21 | 0.33 | 27.38 | 51 | 0.8 | 0.98 |

| Bark | Mixed with Milk and honey | Internal | Diarrhea and dysentery | ||||||||||

| Rosaceae | |||||||||||||

| 95 | Eriobotrya japonica Thumb. Lindler/mh-142 | Loquat | Tree | Leaves | Poultice | External | Swellings | 0.36 | 0.5 | 42.86 | 44 | 0.69 | 0.89 |

| Fruits | Eaten | Internal | Sedative, vomiting | ||||||||||

| Leaves | Infusion | Internal | Relieve diarrhea | ||||||||||

| Flowers | Infusion | Internal | Tea | ||||||||||

| 96 | Prunus armeniaca Linn./mh-144 | Hari, khubani, apricot | Tree | Fruit | Eaten | Internal | Laxative | 0.14 | 0.33 | 23.81 | 31 | 0.48 | 0.39 |

| Seed | Oil | External | Softening effect on the skin | ||||||||||

| 97 | Prunus domestica Linn./mh-145 | Lucha, Alu bukhara | Tree | Fruit | Eaten | Internal | Irregular menstruation, debility, miscarriage, used for alcoholic beverages and liqueurs | 0.43 | 0.33 | 38.1 | 34 | 0.53 | 0.84 |

| 98 | Prunus persica Linn. Batch/mh-146 | Aru, peach | Tree | Leaves | Juice | Internal | Gastritis, whooping cough and bronchitis, kill intestinal worms, remove maggots from wounds in cattle and dogs | 0.36 | 0.5 | 42.86 | 44 | 0.69 | 0.88 |

| 99 | Pyrus malus L./mh-147 | Saib | Tree | Fruit | Juice, paste | Internal | Rheumatism, hypertension, tonic for vigorous body, strengthen bones, face spots | 0.36 | 0.5 | 42.86 | 46 | 0.72 | 0.81 |

| 100 | Pyrus pashia Ham.ex D. Don/mh-148 | Butangi | Tree | Fruit | Eaten | Internal | Dark circles around the eyes, constipation | 0.14 | 0.33 | 23.81 | 49 | 0.77 | 0.95 |

| 101 | Rosa brunonii Lindl./mh-151 | Chal, tarni, musk rose | Shrub | Flower | Decoction | Internal | Constipation | 0.5 | 0.83 | 66.67 | 57 | 0.89 | 0.98 |

| Flowers | Powder | Internal | Diarrhea, heart tonic, skin and eye diseases | ||||||||||

| Leaf | Juice | External | Cuts, wounds | ||||||||||

| 102 | Rubus fruticosus Hk f. non L/mh-153 | Garachey | Shrub | Leaves | Infusion | Internal | Diarrhea, fever | 0.21 | 0.5 | 35.71 | 32 | 0.5 | 0.59 |

| Bark | Soaking | Internal | Diabetes | ||||||||||

| 103 | Rubus niveus Thunb./mh-154 | Garachey | Shrub | Leaves | Extract | External | Urticaria | 0.5 | 0.67 | 58.33 | 41 | 0.64 | 0.69 |

| Leaves | Powder | Internal | Diarrhea, fever, and diuretic | ||||||||||

| Root | Decoction | Internal | Dysentery, colic pains, whooping coughs | ||||||||||

| 104 | Duchesnea indica (Andrews) Teschem/mh-155 | Budimewa | Herb | Fruit | Juice | Internal | Eye infection, tonic | 0.14 | 0.33 | 23.81 | 33 | 0.52 | 0.61 |

| 105 | Fragaria nubicola Lindl. ex Lacaita/mh-157 | Budi meva, Wild Straberry | Herb | Fruit | Chewed | Internal | Laxative, purgative, mouth infection | 0.21 | 0.33 | 27.38 | 35 | 0.55 | 0.5 |

| Rubicaceae | |||||||||||||

| 106 | Galium aparine L./mh-158 | Lainda | Herb | Aerial parts | Powder | External | Bleeding | 0.07 | 0.17 | 11.9 | 15 | 0.23 | 0.31 |

| 107 | Galium asperifolium Wall/mh-159 | Lainda | Herb | Aerial parts | Juice | Internal | Diuretic, kidney infections | 0.14 | 0.33 | 23.81 | 22 | 0.34 | 0.38 |

| Rutaceae | |||||||||||||

| 108 | Skimmia laureola DC. Sieb/mh-161 | Tree | Tree | Leaves | Powdered | External | Smallpox, worm problems, colic | 0.21 | 0.5 | 35.71 | 48 | 0.75 | 0.59 |

| 109 | Zanthoxylum armatum DC. Prodr/mh-162 | Timbar | Shrub | Fruit, branches | Juice | Internal | Gas trouble, cholera, stomach disorder, piles, gum, toothache, indigestion | 0.64 | 0.67 | 65.48 | 60 | 0.94 | 1.13 |

| Seed | Powder, chewed | Internal | Stomach problems, toothache | ||||||||||

| Salicaceae | |||||||||||||

| 110 | Salix acmophylla Boiss./mh-164 | Beens, bed, gaith | Tree | Leaves | Paste, boiled with Robinia pseudoacacia and Cotula anthemoids | Internal | Boils, hernia, fever and swelling of joints | 0.36 | 0.67 | 51.19 | 51 | 0.8 | 0.98 |

| Branch | Chewing | Internal | Stomach problems | ||||||||||

| 111 | Salix denticulate Andersson/mh-166 | Beens | Tree | Stem and root bark | Boiled | Internal | Fever, headache and paralysis | 0.29 | 0.67 | 47.62 | 34 | 0.53 | 0.39 |

| Leaves, branches | Paste | External | Itching and allergy | ||||||||||

| Sambucaceae | |||||||||||||

| 112 | Sambucus wightiana Wall. ex Wight & Arn./mh-167 | Gandala | Herb | Fruit | Eaten | Internal | Stomach problems, expel worms | 0.14 | 0.33 | 23.81 | 19 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Sapindaceae | |||||||||||||

| 113 | Sapindus mukorossi Gaertn./mh-168 | Ritha, Soap nut | Tree | Seeds | Powdered | External | Insect killer | 0.14 | 0.33 | 23.81 | 47 | 0.73 | 0.77 |

| Fruits | Rubbing | External | Burns | ||||||||||

| Saxifragaceae | |||||||||||||

| 114 | Bergenia ciliate Haw. Sternb./mh-170 | Zakhm-e-Hayat | Herb | Aerial parts | Powder | Internal | Urinary tract troubles | 0.36 | 0.5 | 42.86 | 29 | 0.45 | 0.39 |

| Leaves | Juice | External | Earache | ||||||||||

| Root | Juice | Internal | Cough and cold, kidney stones | ||||||||||

| Scorphulariaceae | |||||||||||||

| 115 | Verbascum thapsus L./mh-172 | Gider tabacoo | Herb | Roots | Decoction | Internal | Toothache, cramps, convulsions | 0.21 | 0.33 | 27.38 | 17 | 0.27 | 0.25 |

| Smilicaceae | |||||||||||||

| 116 | Smilax glaucophylla Klotroch/mh-174 | Epiphyte | Epiphyte | Aerial parts | Infusion | Internal | Flatulence, fever, dog bite and spasm | 0.29 | 0.67 | 47.62 | 32 | 0.5 | 0.55 |

| Ulmaceae | |||||||||||||

| 117 | Celtis caucasica Willd/mh-175 | Batkaral | Tree | Aerial parts | Juice | Internal | Colic and amenorrhea | 0.14 | 0.33 | 23.81 | 17 | 0.27 | 0.45 |

| Urticaceae | |||||||||||||

| 118 | Debregeasia salicifolia D. Don Rendle/mh-178 | Sandari | Shrub | Aerial parts | Paste | External | Skin rashes, dermatitis and eczema | 0.21 | 0.17 | 19.05 | 15 | 0.23 | 0.41 |

| Valerianaceae | |||||||||||||

| 119 | Valeraina jatamansi Joes./mh-179 | Herb | Herb | Aerial parts | Oil | Internal | Constipation | 0.07 | 0.17 | 11.9 | 19 | 0.3 | 0.41 |

| Violaceae | |||||||||||||

| 120 | Viola canescens Wall.ex Roxb./mh-181 | Banafsha | Herb | Leaves | Juice | Internal | Cough, cold, fever, jaundice | 0.29 | 0.5 | 39.29 | 51 | 0.8 | 0.84 |

| 121 | Viola pilosa Blume./mh-182 | Banafsha | Herb | Leaves | Decoction | Internal | Pain, fever, stomach ulcer | 0.21 | 0.5 | 35.71 | 47 | 0.73 | 0.81 |

Key words: Rel BS = Relative number of body system treated by a single species; Rel PH = Relative number of pharmacological properties for a single plant; RI = Relative importance, FC = Frequency of citation; RFC = relative frequency of citation; UV = Use Value

Table 4. Informant consensus factor for different disease categories.

| Disease Categories | Symptoms | Ntax | Nur | Fic | Most Commonly Used Plants | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Musculoskeletal and nervous system | Nervous problem, weakness, muscular pains, sedative, cramps, colic, depression, paralysis | 22 | 197 | 0.89 | Hypericum perforatum, Juglans regia, Pyrus malus, Heracleum cachemirica, Heracleum candicans, |

| 2 | Gastro-intestinal, parasitic and hepatobiliary | Liver and bile diseases, jaundice, vomiting, dyspepsia, hepatic pain, dysentery, loss of appetite, anthelmintic, improve digestion, nausea, piles, intestinal parasites, stomach ache, constipation, flatulence, diarrhea, hernia, cholera, gas trouble | 114 | 1162 | 0.90 | Mentha royleana, Zanthoxylum armatum, Berberis lycium, Eriobotrya japonica, Punica granatum, Ziziphus numelaria, Artemisia absinthium |

| 3 | External injuries, bleeding | Swellings, wounds, rheumatism, nail wound, inflammations, Joints pain, pain, burns, cuts and wounds, body inflammation, bone fracture, boils, burns, back pain, bleeding | 65 | 552 | 0.88 | Hypericum perforatum, Berberis lycium, Sapindus mukorossi, Adiantum venustum, Rumex dentatus |

| 4 | Urinogenital and venereal | Urinary problems, menorrhagia, miscarriage, abortion, amenorrhea, irregular menstruation, leucorrhoea, kidney stones, gonorrhea, contraceptive, debility | 16 | 91 | 0.83 | Aesculus indica, Prunus domestica, Bergenia ciliata, Galium asperifolium, Oenothera rosea, Eriobotrya japonica, |

| 5 | Blood and lymphatic system | Anemia, Hypertension, blood purifier. | 15 | 76 | 0.81 | Dalbergia sissoo, Rosa brunonii, Berberis lycium, Vibernum nervosum, |

| 6 | Cardiovascular disease | Heart tonic | 6 | 25 | 0.79 | Rosa brunonii, Oenothera rosea, Viola canscens, Adiantum capillus-veneris |

| 7 | Pulmonary disease | Respiratory problem, cough, difficult breathing, diseases of the lungs, chest pain, asthma, bronchitis, Flue | 41 | 236 | 0.83 | Mentha royleana, Polygonatum multiflorum, Punica granatum, Pyrus pashia, Salvia moorcroftiana, Prunella vulgaris |

| 8 | Dermatological | Skin problems, scabies, leukoderma, smallpox, warts, ulcers, urticaria, pimples, itching and allergy, freckles, cracked heels, measles, leprosy, dark circles around the eyes | 47 | 306 | 0.85 | Fumaria indica, Adiantum incisum, Euphorbia wallichii, Gallium asperifolium, Rosa brunonii |

| 9 | Oral, dental, Hair and ENT | Toothache, strengthen spongy gums, mouth infection, eye sight weakness, earache, flue and cough, sore throats, gum infection, pyorrhea, dandruff, hair tonic, headache | 38 | 186 | 0.80 | Rosa brunonii, Androsace rotundifolia, Bergenia ciliata |

| 10 | Other (fever, tonic, cold, tumors) | Tonic, sun burns, tumors, typhoid, fevers, colds, tumors, cooling agent, demulcent laxative, soft drinks. | 45 | 258 | 0.83 | Fumaria indica, Adiantum incisum, Asparagus filicinus, Castanea sativa, Viola canscens, Trichodesma indicum, Punica granatum, Berberis lycium, Lagustrum lucidam |

| 11 | Antidote | Snake bite, scorpion sting, dog bite | 8 | 31 | 0.77 | Nerium oleander, Dioscorea deltoidea, Hypericum perforatum |

| 12 | Insectiside | Anti lice, antiseptic, helminthiasis | 9 | 27 | 0.69 | Juglans regia, Poa nepalensis, Desmodium polycarpum |

| 13 | Diabetes | Diabetes | 6 | 36 | 0.86 | Berberis lycium, Clematis montana, Rubus fruticosus, |

Fig 2. Life form contribution of ethnomedicinal-flora.

Plant part(s) used

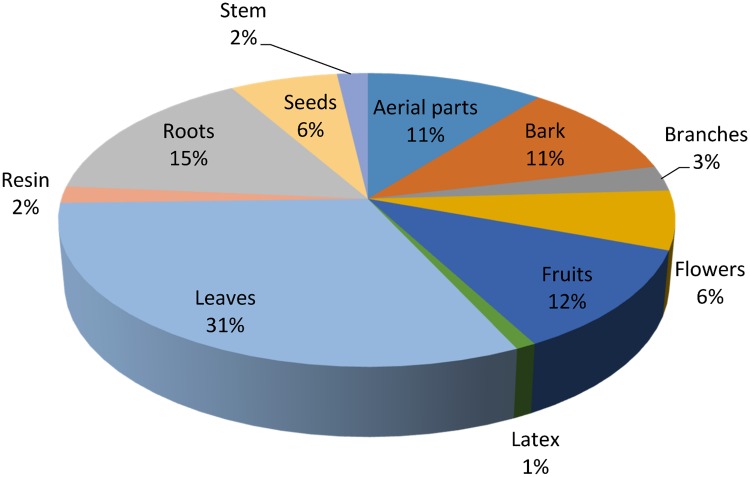

Different plant parts are used differently in herbal medicines depending upon the cultural knowledge and availability of those parts to local inhabitants. In the present study, leaves (31%) were the most commonly used plant part utilized in herbal preparations followed by roots (15%), fruits (12%), bark and other aerial parts (11% each), and flowers and seeds (6% each) (Fig 3). Leaves are frequently used in herbal preparations due to their active secondary constituents. It is thought that leaves contain more easily extractable phytochemicals, crude drugs and many other mixtures which may be proven as valuable in phytotherapy [5, 50–51]. This may be the reason for several studies, including this one, reporting leaves as the most highly exploited plant part for medicinal uses [26, 52]. Besides leaves, roots are also favored parts in many cases possibly because they also contain higher concentrations of bioactive compounds than other plant parts [53–56]. In a few cases, the same plant parts are used to treat different diseases, for example, the roots of Berberis lycium are used internally for the treatment of chronic diarrhea, piles, diabetes, pustules and scabies while externally they are used to cure fractured bones and swellings. Similar uses of many other plants were also recorded (presented in Table 3).

Fig 3. Plant parts used in herbal recipes.

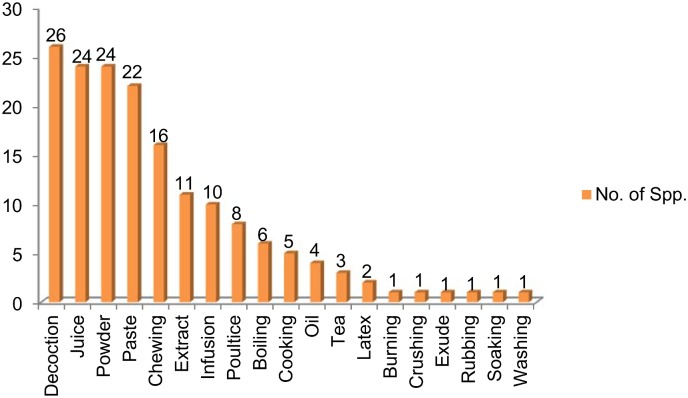

Method of preparation and administration

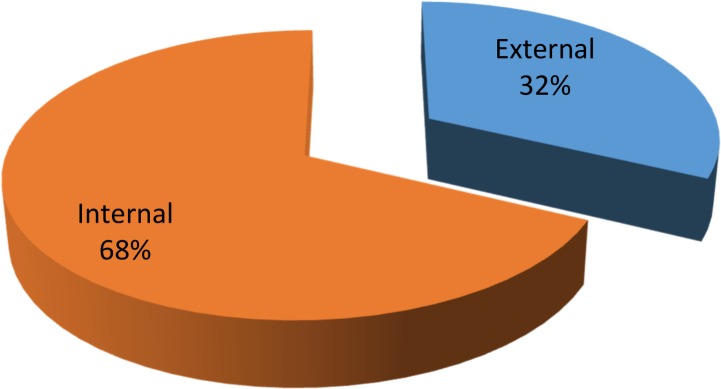

The various plant parts were mostly used in decoctions (26 species) during herbal preparations, followed by juice and powder (24 species each), paste (22), chewing (16 species), extract (11 species), infusion (10 species) and poultice (8 species) (Fig 4), while considering the method of preparation and administration of herbal medicines, reports included decoction, paste, juice, powder or freshly taken. Decoctions are often found to be one of the major forms of preparation in ethnobotanical practice as they are easy to prepare by mixing with water, tea or soup [57]. The most frequent use of decoction might also be due to the fact that heating can cause acceleration of biological reactions resulting in the increased availability of many active compound [58–60]. Similar findings have also been reported by other studies. For example, among major forms of preparation in Madhupur forest area, Bangladesh, decoction was the most frequent (33%), followed by juice (24%), paste (18%), fruit (8%), oil (6%), vegetable (4%), latex (2%), powder (2%) and others (3%) [61]. Similar results are reported also from other parts of the world. Nondo et al. [62], for example, reported medicinal plants to treat malaria in the Kagera and Lindi regions of Tanzania. Among 108 plants most were taken orally or in the form of a decoction. Similarly Siew et al. [63] reported decoction as the main preparation method while documenting traditional uses of 104 plants from Singapore. The quantity and dosage of medicinal drugs is not fixed and differs with age, state of health of the patient and the severity of the disease. Most of the plants were used on their own, but in some herbal preparations specific plant parts were mixed with other ingredients in order to treat an ailment, including milk, honey, oil or butter. A few species were used in combination with other herbs, for example, the leaves of Salix acmophylla were boiled with Robinia pseudoacacia and Cotula anthemoids to treat fever and hernia. Most of the herbal preparations were taken internally (68%) with a smaller number used externally (32%) (Fig 5).

Fig 4. Methods of prepration of herbal recipes.

Fig 5. Mode of application of folk recipes.

Informant consensus factor

The Informant consensus factor (Fic) depends upon the availability of plants within the study area to treat diseases. In the present study, the Fic values ranged from 0.90 to 0.69 with an average of 0.82 which reflects a high consensus among the informants about the use of plants to treat ailments. The ailments are classified into 13 different categories and the maximum Fic value is for gastro-intestinal, parasitic and hepatobiliary complaints and the most cited plants used under this category are Mentha royleana, Zanthoxylum armatum, Berberis lycium, Eriobotrya japonica, Punica granatum, Ziziphus numelaria and Artemisia absinthium. A plant with insecticidal properties has the lowest Fic value of 0.69 which indicates that there is less awareness of people in the study area to use plants as insecticides (Table 4). Gastro-intestinal disorders were prevalent in the study area which can be attributed to limited availability of hygienic food and drinking water [64–65]. The plants frequently used to treat these disorders might contain active ingredients and thus were well known by locals. Among various classes of indigenous uses across the globe, various types of gastrointestinal disorders are predominant and a significant number of plant species have been discovered to cure such illnesses across different ethnic communities [66–67]. Ethnopharmaecological studies have shown that in some parts of the world, gastrointestinal disorder is a first use category [37, 42, 68–70]. A high Fic for gastrointestinal disorders has also been reported by other studies [9, 71–72] although there had previously been no study conducted in our study region. Our findings generally agree with previous results [16, 19, 46] while particularly supporting the results of Bibi et al. [73] who reported that digestive problems were the dominant diseases in the Mastung district of Balochistan, Pakistan.

The high ICF values obtained in this study indicate a reasonably high reliability of informants on the uses of medicinal plant species [74], particularly for gastrointestinal complaints, while low ICF values for cardiovascular diseases and antidotes indicate less uniformity of informants' knowledge. Frequently, a high ICF value is allied with a few specific plants with high use reports for treating a single disease category [75], while low values are associated with many plant species with an almost equal or high use reports suggesting a lower level of agreement among the informants on the use of these plant species to treat a particular disease category.

Relative frequency of citation and use value

The RFC shows the local importance of every species with reference to the informants who cited uses of these plant species [76]. In our work, RFC ranges from 0.94 to 0.14 (Table 3). Berberis lycium, Ajuga bracteosa, Prunella vulgaris, Adiantum capillus-veneris, Desmodium polycarpum, Pinus roxburgii, Albizia lebbeck, Cedrella serrata, Rosa brunonii, Punica granatum, Jasminum mesnyi and Zanthoxylum armatum were the most cited ethnomedicinal plant species. These plants are dominant in the study area and the people are, therefore, very familiar with them. Moreover, these species are native to the area and have been known to local cultures over a long time period. Thus their specific properties for curing different diseases have become popularized and well-established among the indigenous people. These results are important as they could form an important research baseline for subsequent evaluation of plant-derived medicinal compounds, potentially resulting in future drug discoveries [77]. The plant species having high RFC values should be subjected to pharmacological, phytochemical and biological studies to evaluate and prove their authenticity for development of marketable products [78]. These species should also be prioritized for conservation as their preferred uses may place their populations under threat due to over harvesting.

The use value (UV) is a measure of the types of uses attributed to a particular plant species. In the present study Berberis lyceum, Ajuga bracteosa, Abies pindrow, Prunella vulgaris, Adiantum capillus-veneris, Desmodium polycarpum and Pinus roxburgii were ascribed UV values of 1.13, 1.13, 1.03, 1.00, 1.00, 0.98, and 0.98 respectively. UV determines the extent to which a species can be used; thus species with a high UV are more exploited in the study area to cure a particular ailment than those with a low UV. It is found that plants having more use reports (UR) always have high UVs while those plants having fewer URs reported by informants have lower UV. It is also observed that plants which are used in some repetitive manner are more likely to be biologically active [79].

As the values for the UV and RFC are dynamic and change with location and with the knowledge of the people, so the values of UV and RFC may vary from area to area and even within the same area. Plants with lower UV and RFC values are not necessarily unimportant, but their low values may indicate that the young people of the area are not aware about the uses of these plants and, therefore that the understanding of their use is at risk of not being transmitted to future generations, thus this knowledge may eventually disappear [80].

This was the first quantitative ethnobotanical investigation to be carried out in the study area; therefore we compared our results with similar quantitative studies carried out in other parts of the country [26, 50, 51]. This revealed that there were differences in most of the cited species and their quantitative values. In a study carried out by Abbasi et al. [26], Ficus carica and Ficus palmata were the most cited species, while Bano et al. [51] reported that Hippophae rhamnoides had the highest use value (1.64) followed by Rosa brunonii (1.47). These differences can be mostly likely accounted for by variations in the vegetation and geo-climate of the study areas and emphasizes the need for more quantitative studies in a wider range of locations, but particularly in the more remote, mountainous regions where there is still a strong reservoir of ethnomedicinal knowledge amongst the indigenous communities.

Relative importance

The species with high RI values are highly versatile and used to treat a number of diseases. The highest RI values were obtained for Berberis lyceum, Ajuga bracteosa, Prunella vulgaris, Adiantum capillus-veneris, Desmodium polycarpum, Pinus roxburgii, Albizia lebbeck, Cedrella serrata and Rosa brunonii, indicating that these plants are widely used in the study area. These plants have high RI values because they are used in treating various body systems, i.e. local people have considerable knowledge about these plants. The importance of a plant increases as it is used to treat more infirmities [81].

Jaccard index (Novelty index)

Due to differences in their origins and cultures, indigenous communities differ greatly in their ethno-botanical knowledge. Documenting and comparing this knowledge can reveal the considerable depth of knowledge among communities which can result in novel sources of drug development [82]. Such studies also point out the importance of indigenous knowledge on medicinal plants, with differences between regions arising as a result of historical [83], ecological [84], phytochemical and even organoleptic [85] differences. The results of the present study were compared with those from twelve national and international studies conducted in areas similar in terms of their cultural values and climatic conditions to the study area (Table 5). The data show that across 121 plant species, the similarity percentage ranges 16.5 from 0 while the dissimilarity percentage ranges from 22.5 to 1.05. The highest degree of similarity index was with studies by Khan et al. 2010 [86], Amjad et al. 2015 [30], Ahmed et al. 2013 [87] and Shaheen et al. 2012 [88] with JI values of 32.88, 26.19, 19.12, 18.70 respectively. These studies are all from areas in the vicinity of the study area where ethnic values, historical and ecological factors are similar. In addition, there are similar vegetation types and it is also possible that cross cultural exchange of knowledge could have occurred between indigenous communities, either recently or in the past, which also might provide a reason for the high similarity index values. The lowest JI values were for the studies conducted by Kichu et al. 2015 [89] and Bahar et al. 2013 [90]. These studies were carried out at a greater distance from our study location, and thereby reflect a greater difference in ethno-botanical knowledge due to differences in population size, species diversity and habitat structure. Furthermore there would be less chance of the exchange of cultural knowledge between the areas were these studies were conducted and our study location as the areas are isolated by mountain ranges and cultural variations. These findings are in agreement with studies carried out by Kyani and coworker [91] and Ijaz and his coworker [29]. This comparative analysis strengthens the value of the ethnobotanical knowledge from our study location by emphasizing the novelty of our findings, whilst also providing a basis for future studies.

Table 5. Jaccard index comparing the present study with previous reports at regional, national and global scales.

| Area | Study year | Number of recorded plant species | Plants with similar use | Plants with dissimilar use | Total species common in both area | Species enlisted only in aligned areas | Species enlisted only in study area | % of plant with similar uses | % of dissimilar uses | JI | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poonch Valley, Azad Kashmir, Pakistan | 2010 | 169 | 28 | 20 | 48 | 121 | 73 | 16.6 | 11.8 | 32.9 | [86] |

| Pir Nasoora National Park Azad Kashmir, Pakistan | 2015 | 104 | 10 | 23 | 33 | 71 | 88 | 9.62 | 22.1 | 26.2 | [12] |

| 30Bana Valley, Azad Kashmir, Pakistan | 2015 | 86 | 5 | 15 | 20 | 66 | 101 | 5.81 | 17.4 | 13.6 | [92] |

| Bagh, Azad Kashmir, Pakistan | 2012 | 71 | 7 | 16 | 23 | 48 | 98 | 9.86 | 22.5 | 18.7 | [88] |

| Neelum valley, Azad Kashmir, Pakistan | 2011 | 40 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 33 | 114 | 5 | 12.5 | 5 | [93] |

| Leepa valley, Azad Kashmir Pakistan | 2012 | 36 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 29 | 114 | 11.1 | 8.33 | 5.15 | [94] |

| Patriata, New Muree, Pakistan | 2013 | 93 | 8 | 18 | 26 | 67 | 95 | 8.6 | 19.4 | 19.1 | [87] |

| Abbottabad, KPK, Pakistan | 2016 | 74 | 6 | 8 | 14 | 60 | 107 | 8.11 | 10.8 | 9.15 | [26] |

| Alpine and Subalpine region of Pakistan | 2015 | 125 | 6 | 11 | 17 | 108 | 104 | 4.8 | 8.8 | 8.72 | [22] |

| Naran valley, Paksitan | 2013 | 101 | 9 | 18 | 27 | 74 | 94 | 8.91 | 14.87 | 13.85 | [95] |

| Nagaland, India | 2015 | 135 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 132 | 118 | 0 | 2.22 | 1.21 | [89] |

| Madonie Regional Park, Italy | 2013 | 174 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 171 | 118 | 0 | 1.72 | 1.05 | [11] |

| Marmaris, Turkey | 2013 | 64 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 61 | 118 | 0 | 4.69 | 1.7 | [90] |

Statistical analysis

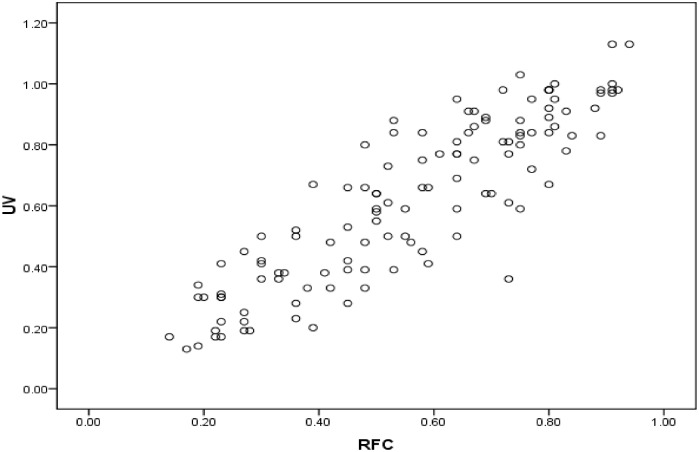

The Pearson correlation coefficient between UV and RFC is 0.881 which reflects that there is a significant and positive correlation between the proportion of uses of a plant species within a sample of interviewed people and the number of times that a particular use of a species is mentioned by the informant (Table 6). This shows that with an increase in the number of informants the knowledge of the uses of a particular species also increases. These results indicate that the study can make a significant contribution to folk knowledge on the use of medicinal plants and further laboratory-based investigations could help in identifying the active ingredients of the most commonly exploited plants. The coefficient of determination defined as r2 determines the degree of variation among the data. In the present study the value of R2 is 0.77 which means that 77% of the variability in UV can be explained in terms of the RFC [25, 59]. Fig 6 illustrates the positive correlation between the values of RFC and UV.

Table 6. Relationship between Use value (UV) and Relative frequency of citation (RFC).

| Correlations | UV | RFC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| UV | Pearson Correlation | 1 | .881** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | ||

| N | 121 | 121 | |

| RFC | Pearson Correlation | .881** | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | ||

| N | 121 | 121 |

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2 -tailed).

R2 = 0.77

Fig 6. Association between use value and relative frequency of citation.

Conclusions

This paper reviews 121 species which are identified as being exploited by local people for their recognized importance in indigenous health care in the Toli Peer National Park. The most common plants in the study area with an ethnomedicinal value are Berberis lycium, Ajuga bracteosa, Prunella vulgaris, Adiantum capillus-veneris, Desmodium polycarpum, Pinus roxburgii, Albizia lebbeck, Cedrella serrata, Rosa brunonii, Punica granatum, Jasminum mesnyi and Zanthoxylum armatum, all of which have high UV, RFC and relative importance values. The Pearson correlation coefficient between UV and RFC is 0.881, with a p value <1, which reflects a significant positive correlation between the use value and relative frequency of citation. The coefficient of determination value is 0.77 which means that 77% of the variability in the UV can be explained in terms of the RFC. The wild plant diversity in this remote National Park provides an effective and cheap source of health care for the local people. The plants employed in their indigenous herbal preparations could have great potential and should be subject to pharmacological screening, chemical analysis for bioactive ingredients and potential formulation as standard drug preparations to cure a range of ailments. The flora of the National Park is currently threatened by overgrazing, deforestation, and soil erosion which are the main causes of reduction of medicinal and other plants in the area. It is therefore essential to have a conservation strategy for the flora of the National Park, with special emphasis on species that are valued as medicinal plants.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to people of Toli Peer National Park who share their value able information during the study. Taxonomic assistance provided by Dr. Mushtaq Ahmed and Muhammad Ilyas are also greatly acknowledged.

Data Availability

All the data is provided in the manuscript.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the The IDEA WILD USA (http://www.ideawild.org/). The IDEA WILD of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (http://www.sare.org/) provided research instrument and funding to carry out field survey. None of the current authors were PIs on the initial grants and the authors do not have a record of the grant numbers. Funding to support student research collaborators was received from Women University of Azad Jammu & Kashmir and PMAS- University of Arid Agriculture Rawalpindi, Pakistan. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Amjad M.S., Arshad M., 2014. Ethnobotanical inventory and medicinal uses of some important woody plant species of Kotli, Azad Kashmir, Pakistan. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine 4, 952–958. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arshad M., Ahmad M., Ahmed E., Saboor A., Abbas A., Sadiq S., 2014. An ethnobiological study in Kala Chitta hills of Pothwar region, Pakistan: multinomial logit specification. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 10, 13 10.1186/1746-4269-10-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Husain S.Z., Malik R.N., Javaid M., Bibi S., 2008. Ethonobotanical properties and uses of medicinal plants of Morgah biodiversity park, Rawalpindi. Pakistan Journal of Botany 40, 1897–1911. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahmood A., Mahmood A., Tabassum A., 2011a. Ethnomedicinal survey of plants from District Sialkot, Pakistan. Journal of Applied Pharmacy 2, 212–220. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmad M., Sultana S., Fazl-i-Hadi S., Ben Hadda T., Rashid S., Zafar, et al. 2014. An Ethnobotanical study of Medicinal Plants in high mountainous region of Chail valley (District Swat-Pakistan). Journal of Ethnobiolgy and Ethnomedicine 10, 4269–4210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balick M.J., 1996. Transforming ethnobotany for the new millennium. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thirumalai T., Beverly C.D., Sathiyaraj K., Senthilkumar B., David E., 2012. Ethnobotanical Study of Anti-diabetic medicinal plants used by the local people in Javadhu hills Tamilnadu, India. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine 2, S910–S913. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baydoun S., Chalak L., Dalleh H., Arnold N., 2015. Ethnopharmacological survey of medicinal plants used in traditional medicine by the communities of Mount Hermon, Lebanon. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 173, 139–156. 10.1016/j.jep.2015.06.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tangjitman K., Wongsawad C., Kamwong K., Sukkho T., Trisonthi C., 2015. Ethnomedicinal plants used for digestive system disorders by the Karen of northern Thailand. Journal of ethnobiology and ethnomedicine 11, 27 10.1186/s13002-015-0011-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ali H., Qaiser M., 2009. The ethnobotany of Chitral valley, Pakistan with particular reference to medicinal plants. Pakistan Journal of Botany 41, 2009–2041. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alam N., Shinwari Z., Ilyas M., Ullah Z., 2011. Indigenous knowledge of medicinal plants of Chagharzai valley, District Buner, Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Botany 43, 773–780. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kargoglu M., Cenkci S., Serteser A., Evliyaoglu N., Konuk M., Kok M.S., et al. 2008. An Ethnobotanical Survey of Inner-West Anatolia, Turkey. Human Ecology 36, 763–777. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ratnam F., Raju I., 2008. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by the Nandi people in Kenya. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 116, 370–376. 10.1016/j.jep.2007.11.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jamila F., Mostafa E., 2014. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used by people in Oriental Morocco to manage various ailments. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 154, 76 87. 10.1016/j.jep.2014.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Safa O., Soltanipoor M.A., Rastegar S., Kazami M., Dehkord K.N., Ghannadi A., 2012. An ethnobotanical survey on Harmozgan Province, Iran. Avicenna Journal of Phytomedicine 3 (1), 64–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nasab K.F., Khosravi A.R., 2014. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants of Sirjan in Kerman Province, Iran. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 154, 190–197. 10.1016/j.jep.2014.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh H., Husain T., Agnihotri P., Pande P.C., Khatoon S., 2014. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used in sacred groves of Kumaon Himalaya, Uttarakhand. Indian Journal of Ethnopharmacology 154, 98–108. 10.1016/j.jep.2014.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhatti G.R., Qureshi R., Shah M., 2001. Ethnobotany of Qadanwari of Nara Desert. Pakistan Journal of Botany, 801–812 (Special issue). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qureshi R., 2002. Ethnobotany of Rohri Hills, Sindh, Pakistan. Hamdard Medicus 45 (3), 86–94. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khan S.W., Khatoon S., 2004. Ethnobotanical studies in Haramosh and Bugrote Valleys (Gilgit). International Journal of Biotechnology 1 (4), 584–589. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qureshi R., Bhatti G.R., 2008. Ethnobotany of plants used by the Thari people of Nara Desert, Pakistan. Fitoterapia 79, 468–473. 10.1016/j.fitote.2008.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shinwari Z.K., 2010. Medicinal plants research in Pakistan. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research 4 (3), 161–176. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farooq S., Barki A., Yousaf Khan M., Fazall H., 2012. Ethnobotanical studies of the flora of Tehsil Birmal in South Wazirestan Agency, Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Weed Science Research 18, 277–291. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abbasi A.M., Mir A.K., Munir H.S., Mohammad M.S., Mushtaq A., 2013. Ethnobotanical appraisal and cultural values of medicinally important wild edible vegetables of Lesser Himalayas-Pakistan. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 9, 84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmad M., Sultana S., Fazl-i-Hadi S., Ben Hadda T., Rashid S., Zafar, et al. 2014. An Ethnobotanical study of Medicinal Plants in high mountainous region of Chail valley (District Swat-Pakistan). Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 10, 4269–4210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khan M.P.Z., Ahmad M., Zafar M., Sultana S., Ali M.I., Sun H., 2015. Ethnomedicinal uses of Edible Wild Fruits (EWFs) in Swat Valley, Northern Pakistan. Journal of ethnopharmacology 173, 191–203. 10.1016/j.jep.2015.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ijaz F., Iqbal Z., UrRahman I., Alam J., Khan S.M., Shah G.M., et al. 2016. Investigation of traditional medicinal floral knowledge of Sarban Hills, Abbottabad, KP, Pakistan. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 179: 208–233. 10.1016/j.jep.2015.12.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamayun, M., Khan, M. A. and Hayat, T., 2005. Ethnobotanical profile of Utror and Gabral Valleys, District Swat, Pakistan. www.ethnoleaflets.com/leaflets/swat.

- 29.Sadeghi Z., Kuhestani K., Abdollahi V., Mahmood A., 2014. Ethnopharmacological studies of indigenous medicinal plants of Saravan region, Baluchistan. Iranian Journal of Ethnopharmacology 153, 111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amjad M.S., Arshad M., Qureshi R., 2015. Ethnobotanical inventory and folk uses of indigenous plants from Pir Nasoora National Park, Azad Jammu and Kashmir. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine 5, 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahmood A., Qureshi R.A., Mahmood A., Sangi Y., Shaheen H., Ahmad I., et al. 2011b. Ethnobotanical survey of common medicinal plants used by people of district Mirpur, AJK, Pakistan. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research 5, 4493–4498. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khan M.A., Khan M.A., Hussain M., 2012. Ethnoveterinary medicinal uses of plants of Poonch valley Azad Kashmir. Pakistan Journal of Weed Science Research 18, 495–507. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khan, M. A. 2008. Biodiversity and Ethnobotany of Himalayan Region Poonch Valley, Azad Kashmir Pakistan. Ph.D Thesis. Quaid-iAzam University Islamabad, Pakistan. 241pp.

- 34.Faiz A. H., Ghufarn M.A., Mian A., Akhtar T. 2014. Floral Diversity of Tolipir National Park (TNP), Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan. Biologia (Pakistan) 60 (1), 43–55. [Google Scholar]