Abstract

Objective

This study was to evaluate the safety and efficiency of endovascular treatment of unruptured basilar tip aneurysms.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed consecutive 79 cases of unruptured basilar tip aneurysms in our center between 2009 and 2014. The patients’ clinical and imaging information were recorded. Complications, initial occlusion rate, clinical outcomes and the predictors were retrospectively analyzed.

Results

Thirty-five cases received conservative treatment and 44 cases were treated by endovascular embolization. In the conservative treatment group, six (19.4%) of 31 basilar tip aneurysms ruptured and resulted in five deaths (16.1%) during the mean 18.1-month follow-up (range from 1 to 60 months). Among the endovascularly treated cases, 24 (54.5%) achieved initial complete occlusion and no delayed hemorrhagic events occurred during the mean 33.6-month follow-up (range from 10 to 68 months). For 20 (45.5%) incompletely occluded cases, five postoperative or delayed hemorrhagic events and two mass effect events resulted in six deaths. There were no statistical significant differences in hemorrhagic events (p = 0.732) and mortality (p = 0.502) between the incomplete occlusion group and untreated group. Large aneurysm size (≥10 mm) was an independent predictor for incomplete occlusion (p = 0.002), which had a potential risk of postoperative or delayed hemorrhage. On univariate analysis, initial occlusion rate and aneurysm size were found to be associated with clinical outcomes (p = 0.042 and 0.015).

Conclusion

Complete occlusion for unruptured basilar tip aneurysm proved to be a safe and effective therapeutic method that could eliminate the potential risk of postoperative or delayed hemorrhage.

Keywords: Unruptured basilar tip aneurysm, incomplete occlusion, delayed hemorrhage, clinical outcome

Introduction

Ruptured basilar tip aneurysms may result in fatal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) and mortality could be as high as 23%.1,2 Owing to the proximity of the brainstem, difficulty in obtaining adequate exposure and crowding of arteries in this region, surgical clipping for basilar tip aneurysms remains a challenge and the procedure-related mortality and morbidity could be 9% and 19.4%.3–6 Endovascular coiling with or without stent has become an important option for treating these aneurysms.7,8 However, there was no sufficient experience referring to the long-term clinical outcomes of unruptured basilar tip aneurysms that were occluded completely or incompletely. In this study, we retrospectively reviewed these aneurysms, endovascularly treated and untreated, to evaluate the safety and efficacy of endovascular embolization.

Patients and methods

From January 2009 to August 2014, 79 consecutive cases of unruptured basilar tip aneurysms were retrospectively reviewed. All patients signed the informed consents to participate in this study before they received endovascular treatment, and the study was approved by the ethics committee of Beijing Tiantan Hospital. Patient demographics and characteristics of aneurysms are summarized in Table 1. There were 52 (65.8%) females and 27 (34.2%) males, and patient ages ranged from 13 to 78 years (mean 57.3 ± 10.6 years). All of these cases had no SAH history. Demographic characteristics, computed tomography angiography (CTA), magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), digital subtracted angiography (DSA) and medical reports were collected. Sixteen cases (20.3%) were asymptomatic; 26 (32.9%) cases complained of slight headache or transient dizziness; and 37 (46.8%) cases presented with neurological deficits caused by transient ischemic attack (TIA), ischemic stroke and mass effect. Aneurysmal dome and neck, the parent artery, and the origin and trajectory of nearby arterial branches were identified by cerebral DSA with three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction. Of the 79 unruptured basilar tip aneurysms, diameter ranged from 1.5 mm to 30 mm and mean size was 8.2 mm ± 4.4 mm.

Table 1.

Baseline characters of the patients and aneurysms.

| Characters | Aneurysms (n) (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 57.3 ± 10.6a |

| Gender (female/male) | 52/27(65.8%/34.2%) |

| Asymptomatic | 16(20.3%) |

| Headache or dizziness | 26(32.9%) |

| Neurological disorders | 37(46.8%) |

| Treatment strategy | |

| Stent-assisted coiling | 25(31.6%) |

| Conventional coiling | 19(24.1%) |

| Observed | 35(44.3%) |

| Occlusion rate | |

| Complete(≥95%) | 24(54.5%) |

| Incomplete(<95%) | 20(45.5%) |

| Aneurysm size | |

| <5mm | 15(19.0%) |

| 5∼10 mm | 46(58.2%) |

| 10∼25 mm | 17(21.5%) |

| >25 mm | 1(1.3%) |

| Dome-to-neck ratio | |

| ≥2 | 26(32.9%) |

| <2 | 53(67.1%) |

SD: standard deviation; data in parentheses are percentages.

The refusal of endovascular treatment (common considering the high risk of the lesion or perforating vessels) and technical difficulties (one case failed to navigate the guiding catheter into the vertebral artery and one case could not deliver the stent microcatheter across the neck of the aneurysms) resulted in conservative treatment.

Endovascular treatment included conventional simple coiling and stent-assisted coiling. Stents were used for wide-neck aneurysms that were defined as having a dome-to-neck ratio <2 and irregularly shaped aneurysms. Antiplatelet therapy consisted of clopidogrel 75 mg/day and aspirin 100 mg/day for at least three days before implantation of stents. During procedures, a bolus of heparin was administered using 3000 IU, and then 1000 IU per hour. After procedures, patients who were treated by stent-assisted coiling received clopidogrel therapy (75 mg/d) for four to six weeks and aspirin therapy (100 mg/d) for at least six months. For treated cases, occlusion rates were assessed by the three-point Roy-Raymond scale (complete occlusion, neck remnant, and residual sac). We considered the slight residual neck or 95% to 100% occlusion rate as complete occlusion and the residual part of the aneurysmal sac as incomplete occlusion.

Clinical follow-up was supplemented by telephone interview or outpatient interview. Angiographic follow-up was obtained for endovascularly treated patients. A modified Rankin Score (mRS) ≤ 2 was defined as good clinical outcome.

Statistical analysis

Normally distributed continuous data were presented as mean ± SD and categorical data as frequency and percentage. Univariate logistic regression analysis was used to identify the predictors of incomplete occlusion and long-term clinical outcomes. The Fisher exact test, x2 test, independent-sample t-test and Kaplan-Meier analysis were performed to compare the complications, postoperative or delayed hemorrhagic events and mortality among the complete occlusion, incomplete occlusion and untreated groups. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was carried out with SPSS version 17.0.

Results

Angiographic results

Thirty-five cases received conservative treatment and 44 cases were treated by endovascular embolization. In treated cases, initial complete occlusion rate was 54.5% (24 of 44) and incomplete occlusion rate was 45.5% (20 of 44). Stent-assisted coiling procedures were performed in 25 (56.8%) cases (14 incomplete occlusion and 11 complete occlusion) and conventional simple coiling in 19 (43.2%) cases (six incomplete occlusion and 13 complete occlusion). Angiographic follow-up was obtained in 23 (52.3%) cases. Fourteen aneurysms that were occluded completely remained stable and no recurrence was detected. For nine incompletely occluded aneurysms, no significant enlargement of the residual sac was detected.

Complications and follow-up

In the untreated group, technical difficulties did not cause significant procedure-related complications for two cases. One untreated case suffered paralysis, which was caused by thrombosis during the diagnosing angiogram and was relieved in a few days. In 44 treated cases, two (4.5%) intraprocedural rupture events resulted in one permanent neurological deficit; two (4.5%) patients who were occluded incompletely died of mass effect that was caused by the compression of large and giant aneurysms (diameters were 22 mm and 30 mm) after treatment within seven days. Two (4.5%) TIA complications that were caused by occlusion of critical perforating arteries and thrombosis formation of the posterior cerebral artery (PCA) within 72 hours were detected (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of clinical outcomes in different initial occlusion ratio.

| Complete occlusion (n,%)a | Incomplete occlusion (n,%) | p valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 16 (66.7) | 10 (50.0) | 0.359 |

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 57.12 ± 12.90 | 53.30 ± 10.84 | 0.299 |

| Small aneurysm (<10 mm) | 23 (95.8) | 11 (55.0) | 0.002 |

| Treatment strategy | 0.135 | ||

| Stent-assisted coiling | 11 (45.8) | 14 (70.0) | |

| Conventional coiling | 13 (54.2) | 6 (30.0) | |

| Intraprocedural rupture | 1 (4.2) | 1 (5.0) | 1.000 |

| Ischemic | 2 (8.3) | 0 (0) | 0.493 |

| Hemorrhagic events | 0 (0) | 5 (20.0) | 0.014 |

| Deaths | 0 (0) | 6 (30.0) | 0.005 |

SD: standard deviation; data in parentheses are percentages.

Fisher exact test or chi-square test.

Clinical follow-up was available during the mean 18.1-month follow-up (range 1 to 60 months) in 31 untreated cases and mean 29.5-month follow-up (range 1 to 76 months) in 42 treated cases (excluding two cases of mass effect). In the untreated group, SAH occurred in six (19.4%) patients at one month, six months, seven months, 10 months, 26 months and 45 months, and resulted in five deaths (16.1%). There was one patient who died of severe myocardial infarction 10 months later. A total of 25 (80.6%) cases had good clinical outcomes (mRS ≤ 2) during the follow-up.

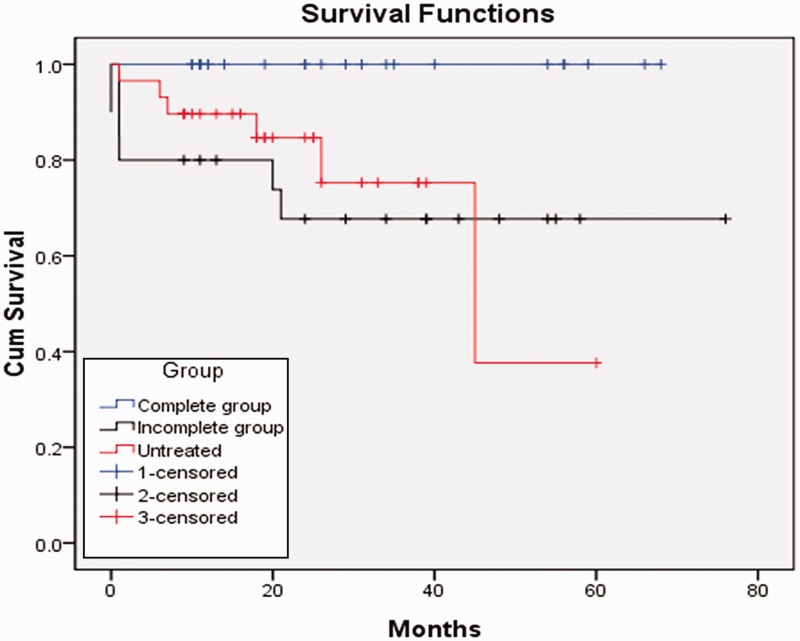

For the 42 treated cases, the overall mortality was 9.5% (four cases) during follow-up. Among the incomplete occlusion group, postoperative or delayed hemorrhagic events occurred in five (27.8%, 5/18) cases at four days, seven days, one month, 20 months and 21 months, and resulted in four deaths and one permanent neurological deficit. The other 13 cases that had mRS scores less than 2 initially had good clinical outcomes. In the complete occlusion group, all 24 cases received a clinical interview and no delayed hemorrhagic events occurred during the follow-up (10 to 68 months, mean 33.6 months). These cases had an mRS score of 2 or less (Figure 1). Figure 2 shows that SAH occurred in a case with incomplete occlusion. Figure 3 shows a case that was occluded completely and had no recurrence according to the angiographic follow-up.

Figure 1.

Graph shows the long-term survival conditions of unruptured basilar tip aneurysms that were treated and not treated. The blue line is the complete occlusion group; the black line is the incomplete occlusion group; the red line means the untreated cases. There is no significant difference in long-term good clinical outcomes between the incomplete occlusion group and untreated group.

Figure 2.

A 60-year-old female presented with headache and numbness. (a) Left vertebral artery angiogram (frontal views) showed an aneurysm at the basilar artery tip location with fenestration. (b) The aneurysm was treated by conventional coiling technology. Postoperative angiogram in frontal views: basilar tip aneurysm was embolized incompletely (white arrow). (c) Emergency postoperative computed tomography (CT) scan showed delayed subarachnoid hemorrhage (white arrow).

Figure 3.

A 61-year-old female presented with left limb numbness and was treated by stent-assist coiling. (a) Right vertebral artery angiogram (frontal views) showed an aneurysm at the basilar artery tip location. (b) After the procedure, the aneurysm was completely obliterated by immediate postoperative angiography. (c) During the eight-month follow-up, cerebral angiography showed the compaction of coils and no recurrence of aneurysm was found.

Statistics analysis

Compared with the untreated cases, endovascular treatment did not improve the clinical outcomes (p = 1.000) excepted for the poor outcomes of incomplete occlusion group during follow-up. In addition, there were no significant differences referring to the intracranial hemorrhagic rate (p = 0.732) and mortality (p = 0.502) between the incomplete occlusion group and untreated group. All cases in the complete occlusion group survived and had significant lower mortality than the incomplete occlusion group (p = 0.005, 0% vs 30%) and untreated group (p = 0.03, 0% vs 19.4%). Large aneurysmal size (Table 3) was an independent predictor for incomplete occlusion (p = 0.002) but wide neck (p = 0.227) and stents (p = 0.135) were not (Table 3). Additionally, according to the univariate regression analysis results, initial incomplete occlusion (p = 0.042) and large aneurysm size (p = 0.015) were associated with poor clinical outcomes (Table 4).

Table 3.

Predictors of aneurysm occlusion rate (univariate analysis).

| Predictors of aneurysm occlusion rate (univariate analysis) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | p value | |

| Aneurysm size | 18.818 | 2.112–167.701 | 0.002 |

| Dome-to-neck ratio | 2.333 | 0.671–8.119 | 0.227 |

| Utilize of stents | 2.758 | 0.791–9.613 | 0.135 |

Table 4.

Predictors for clinical outcomes of endovascularly treated cases.

| Predictors for clinical outcomes of endovascularly treated cases (univariate analysis) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | p value | |

| Age | 1.333 | 0.285–6.232 | 0.715 |

| Sex | 0.833 | 0.190–3.655 | 0.809 |

| Aneurysm size | 0.133 | 0.026–0.674 | 0.015 |

| Hypertension | 2.369 | 0.541–10.615 | 0.25 |

| Occlusion rate | 5.923 | 1.066–32.897 | 0.042 |

| Stents | 1.067 | 0.244–4.664 | 0.932 |

Discussion

Owing to the straight course of the basilar artery, the apex position of artery and the development of embolization techniques, basilar tip aneurysms could be favorable to endovascular navigation and catheterization.9 A previous study reported that occlusion with the Guglielmi detachable coil (GDC) was achieved in 52 (95%) of 55 basilar tip aneurysms and failed in only two (4%) aneurysms.10 Eskridge and Song found that errant coil placement occurred in only three patients (2%, 3/150).2 However, wide-necked aneurysms that were challenging to occlude accounted for approximately 60% in basilar tip aneurysms.11 Several studies have reported various initial angiographic results. In a retrospective study that included 226 coiled basilar tip aneurysms, Lozier et al. reported that the initial complete or near-complete aneurysm occlusion rate was 87.7%.11 Henkes et al. showed a 58% initial complete occlusion rate of basilar tip aneurysm treated by endovascular coiling.12Chalouhi and colleagues treated 235 patients with basilar tip aneurysms, and 206 (87.7%) patients achieved complete or near-complete occlusion.13Galal et al. reported on 43 patients with unruptured or ruptured aneurysms treated with stent placement, and overall complete or near-complete embolization was achieved initially in 60.4% and in 82.1% during the angiographic follow-up.14 In addition, in their study, nine unruptured basilar tip aneurysms were recruited, and the initial complete or near-complete occlusion rate was 66.6%.

Owing to the unfavorable anatomic features such as wide necks, the incorporation of PCAs or superior cerebellar arteries, it is more difficult to achieve satisfactory occlusion for basilar tip aneurysms.12,15 Standhardt and colleagues demonstrated the initial or follow-up complete occlusion rate decreased as the size of dome and neck increased.16 Ferns et al. concluded that aneurysms that were larger than 10 mm and located at the basilar tip usually did not benefit from endovascular treatment.17 Our results were consistent with these previous studies, and we also regarded large aneurysmal size as a predictor of incomplete occlusion. Incomplete occlusion had the potential of loose packing of the aneurysmal sac or neck and could not prevent blood flowing into the residual sac, which increased the risk of recanalization or hemorrhage.18 Byrne et al. reported 11 hemorrhagic events after incomplete coiling occlusion and confirmed this alarming process.19 However, few studies focused on the postoperative or delayed hemorrhage of unruptured basilar tip aneurysms treated with incomplete occlusion.16,20 In our study, the postoperative or delayed hemorrhagic events occurring in the incomplete occlusion group were considered to have no statistical difference compared with the bleeding rate of the untreated group. In addition, incomplete occlusion was associated with poor clinical outcomes. Thus, incompletely occluded unruptured basilar tip aneurysms should be considered as cases of treatment failure as long as they are not re-treated.10

The previous mass effect of giant aneurysms located at the basilar artery tip may result in fatal clinical outcomes.21 Complete occlusion for giant aneurysms, especially posterior circulation aneurysms, was difficult to perform.10 Although endovascular embolization changed the hemodynamics and induced the formation of intra-aneurysm thrombosis, this technique increased the hardness of the aneurysm substantially and did not release the initial compression of brainstem in a short time.22 In our study, two patients with giant basilar tip aneurysms died of mass effect a few days after receiving incomplete occlusion. For the bifurcation aneurysms, especially basilar tip aneurysms, new and advanced treatment techniques or devices are needed. Uncommon endovascular constructs including Y-stent placement and placement across the entire aneurysm neck from PCA to PCA may provide satisfactory occlusion and reconstruction effect. The PulseRider device could also offer an alternative means for stent-assisted coiling that allows for tight coil packing without the need to catheterize the branch vessels.23,24 More data and experience are needed.

Limitations of the study

There are several limitations of our study. First, the quantity of patients was insufficient. Second, not all patients accepted the imaging examination during the follow-up. Third, the comparisons between groups that are not similar or randomized are prone to error.

Conclusion

It is difficult to achieving satisfactory occlusion in large basilar tip aneurysms, and incomplete occlusion is not superior to conservative treatment in preventing aneurysm rupture. The long-term clinical outcomes of patients who embolized completely in our study confirmed the efficacy and safety of this treatment modality.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr Xinjian Yang, Dr Chuhan Jiang and Dr Yuhua Jiang for the data collection.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: this article is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 81471166).

References

- 1.Schievink WI, Wijdicks EF, Piepgras DG, et al. The poor prognosis of ruptured intracranial aneurysms of the posterior circulation. J Neurosurg 1995; 82: 791–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eskridge JM, Song JK. Endovascular embolization of 150 basilar tip aneurysms with Guglielmi detachable coils: Results of the Food and Drug Administration multicenter clinical trial. J Neurosurg 1998; 89: 81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawton MT. Basilar apex aneurysms: Surgical results and perspectives from an initial experience. Neurosurgery 2002; 50: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abla AA, Lawton MT, Spetzler RF. The art of basilar apex aneurysm surgery: Is it sustainable in the future? World Neurosurg 2014; 82: 1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lozier AP, Kim GH, Sciacca RR, et al. Microsurgical treatment of basilar apex aneurysms: Perioperative and long-term clinical outcome. Neurosurgery 2004; 54: 286–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lv X, Li Y, Liu A, et al. Endovascular management of multiple cerebral aneurysms in acute subarachnoid hemorrhage associated with fenestrated basilar artery. A case report and literature review. Neuroradiol J 2008; 21: 137–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henkes H, Fischer S, Weber W, et al. Endovascular coil occlusion of 1811 intracranial aneurysms: Early angiographic and clinical results. Neurosurgery 2004; 54: 268–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peluso JP, van Rooij WJ, Sluzewski M, et al. Coiling of basilar tip aneurysms: Results in 154 consecutive patients with emphasis on recurrent haemorrhage and re-treatment during mid- and long-term follow-up. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2008; 79: 706–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geyik S, Yavuz K, Yurttutan N, et al. Stent-assisted coiling in endovascular treatment of 500 consecutive cerebral aneurysms with long-term follow-up. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2013; 34: 2157–2162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vallee JN, Aymard A, Vicaut E, et al. Endovascular treatment of basilar tip aneurysms with Guglielmi detachable coils: Predictors of immediate and long-term results with multivariate analysis 6-year experience. Radiology 2003; 226: 867–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lozier AP, Connolly ES, Jr, Lavine SD, et al. Guglielmi detachable coil embolization of posterior circulation aneurysms: A systematic review of the literature. Stroke 2002; 33: 2509–2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henkes H, Fischer S, Mariushi W, et al. Angiographic and clinical results in 316 coil-treated basilar artery bifurcation aneurysms. J Neurosurg 2005; 103: 990–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chalouhi N, Jabbour P, Gonzalez LF, et al. Safety and efficacy of endovascular treatment of basilar tip aneurysms by coiling with and without stent assistance: A review of 235 cases. Neurosurgery 2012; 71: 785–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galal A, Bahrassa F, Dalfino JC, et al. Stent-assisted treatment of unruptured and ruptured intracranial aneurysms: Clinical and angiographic outcome. Br J Neurosurg 2013; 27: 607–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jayaraman MV, Do HM, Versnick EJ, et al. Morphologic assessment of middle cerebral artery aneurysms for endovascular treatment. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2007; 16: 52–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Standhardt H, Boecher-Schwarz H, Gruber A, et al. Endovascular treatment of unruptured intracranial aneurysms with Guglielmi detachable coils. Short-and long-term results of a single-centre series. Stroke 2008; 39: 899–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferns SP, Sprengers ME, van Rooij WJ, et al. Late reopening of adequately coiled intracranial aneurysms: Frequency and risk factors in 400 patients with 440 aneurysms. Stroke 2011; 42: 1331–1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tateshima S, Murayama Y, Gobin YP, et al. Endovascular treatment of basilar tip aneurysms using Guglielmi detachable coils: Anatomic and clinical outcomes in 73 patients from a single institution. Neurosurgery 2000; 47: 1332–1339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Byrne JV, Sohn MJ, Molyneux AJ, et al. Five-year experience in using coil embolization for ruptured intracranial aneurysms: Outcomes and incidence of late rebleeding. J Neurosurg 1999; 90: 656–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Apsimon T, Khangure M, Ives J, et al. The Guglielmi coil for transarterial occlusion of intracranial aneurysm: Preliminary Western Australian experience. J Clin Neurosci 1995; 2: 26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Darsaut TE, Darsaut NM, Chang SD, et al. Predictors of clinical and angiographic outcome after surgical or endovascular therapy of very large and giant intracranial aneurysms. Neurosurgery 2011; 68: 903–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lv X, Jiang C, Li Y, et al. Treatment of giant intracranial aneurysms. Interv Neuroradiol 2009; 15: 135–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vasquez C, Hubbard M, Jagadeesan BD, et al. Transfundal stent placement for treatment of complex basilar tip aneurysm: Technical note. J Neurointerv Surg 2015; 7: e33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheth SA, Patel NS, Ismail AF, et al. Treatment of wide-necked basilar tip aneurysm not amenable to Y-stenting using the PulseRider device. J Neurointerv Surg. Epub ahead of print 23 July 2015. DOI: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2015-011836.rep. [DOI] [PubMed]