Abstract

Background

Endovascular therapies (EVTs) are useful for treating cerebrovascular disease. There are few data about the availability of such services at primary stroke centers (PSCs). Our hypothesis was that some of these services may be available at some PSCs.

Methods

We conducted an internet-based survey of hospitals certified as PSCs by the Joint Commission. The survey inquired about EVTs such as intra-arterial (IA) lytics, IA mechanical clot removal, coiling of aneurysms, and cervical arterial stenting, physician training, coverage models, hospital type, and outcomes. Chi-square analyses were used to detect differences between academic and community PSCs.

Results

Data were available from 352 PSCs, of which 75% were community hospitals, 23% academic medical centers, and 80% were non-profit; almost half (48%) see 300 or more patients annually with ischemic stroke. A majority (60%) provided some or all EVTs on site, while 29% had none on site and no plans to add them. Among the respondents offering EVTs, 95% offered stenting of neck vessels, 86% IA lytics, 80% IA mechanical, and 74% aneurysm coiling. The majority (>55%) that did offer such services provided them 24/7/365. Most endovascular coverage was provided by interventional neuroradiologists (60%), fellowship trained endovascular neurosurgeons (42%), and interventional radiologists (41%). The majority of hospitals (81%) did not participate in an audited national registry.

Conclusions

A variety of EVT services are offered at many PSCs by interventionalists with diverse types of training. The availability of such services is clinically relevant now with the proven efficacy of mechanical thrombectomy for ischemic stroke.

Keywords: Acute stroke, endovascular, stroke center

Introduction

Currently in the United States (US) there are almost 1100 primary stroke centers (PSCs) certified by the Joint Commission (JC), and at least 1500 if other certifying agencies are included.1 Other countries also have hundreds of hospitals that operate as PSCs, some of which are certified by various governmental agencies. Some prior reports about care at PSCs have focused on patients with ischemic stroke and the use of intravenous (IV) tissue plasminogen activator (TPA).2,3 Other reports have dealt with processes of care and the utilization of secondary prevention therapies.4

There are many other medical and surgical therapies that may be used at some PSCs for patients with ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes. Among the most important and complex procedures performed at a stroke center, endovascular therapies (EVTs) are of particular importance because of their costs, risks, and outcomes. A number of recent prospective randomized trials have reported the benefits of emergent endovascular clot removal, with or without IV TPA, in patients with acute ischemic strokes due to occlusion of a large intracranial vessel.5–9 These reports have highlighted the need for patient access to EVT for acute ischemic stroke, and focused attention on the availability and location of facilities that can perform such interventions.10

Although many of these patients and interventions are likely to occur at a comprehensive stroke center (CSC), to date there are a limited number of JC-certified CSCs in the US. The distribution of CSCs is uneven and much of the US population does not live close to a CSC.11 Yet it appears that thousands of EVT procedures are performed annually in the US alone, suggesting that the performance of EVTs at PSCs (and other facilities) is a common occurrence of medical significance.12 Yet there is a paucity of data about the availability and use of these interventions at PSCs. This is important for planning patient triage and possible emergency medical services (EMS) diversion of patients in need of EVT for acute stroke.13

To address this issue, we conducted a prospective survey of certified PSCs to determine the availability, operator training, hospital characteristics, and monitoring of outcomes for various EVTs at these facilities. Our hypothesis was that many PSCs were performing a variety of EVTs for various indications, but with unclear monitoring of outcomes.

Methods

The JC sent via email a survey to every hospital that was a certified PSC as of June 2013. The survey inquired about availability of EVTs at the hospital, including the use of intra-arterial (IA) lytics for acute ischemic stroke, endovascular mechanical clot removal, coiling of aneurysms for symptomatic or asymptomatic cerebral aneurysms, and stenting of cervical arteries. Additional questions sought information about hospital type, physician training and specialty, physician coverage paradigms, and how patient outcomes were tracked.

Duplicate responses were either removed or combined to reduce double counting. The number of responding organizations varied for each question. Numbers and percentages were calculated based on the total number of unique responding organizations for each question. Descriptive statistics were used for analysis of most of the respondent data. We used chi-square analysis to examine differences between academic and community PSCs as related to the above parameters and responses.

Results

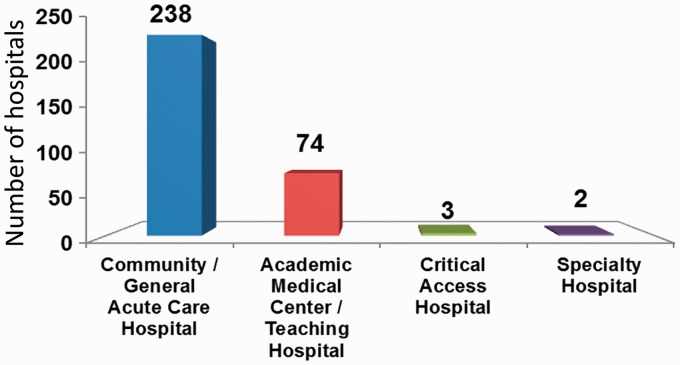

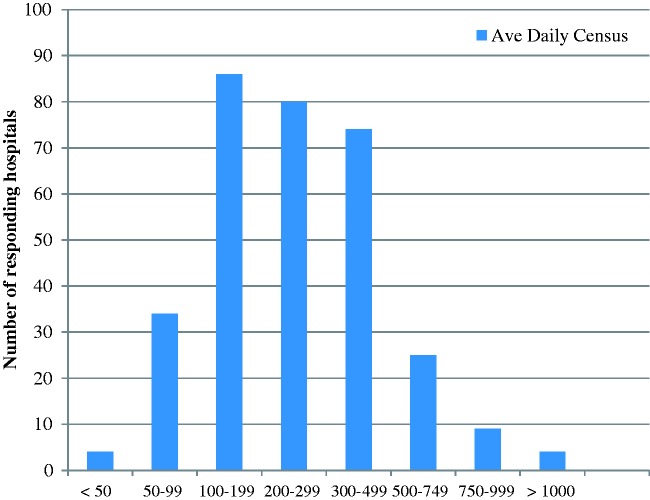

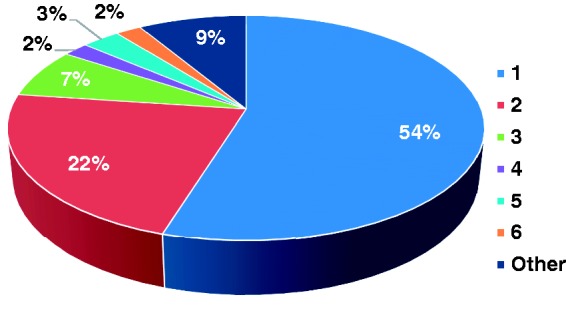

Responses and data were available from 352 certified PSCs (out of 943 surveyed). Among the 317 hospitals that defined their characteristics, 75% were community hospitals, 23% academic centers, and 80% were non-profit organizations (see Figure 1). Hospitals varied significantly in size, with an average daily census of 100–499 for the vast majority of responding organizations. In general, these hospitals saw large numbers of stroke patients, with almost half (48%) seeing 300 or more stroke patients annually with acute ischemic stroke (see Figure 2). A majority (60%) provided some or all EVTs on site, while 29% had none on site and no plans to add them. About 11% of responding PSCs were planning to offer some EVTs at their facilities in the future.

Figure 1.

Hospital characteristics among respondents to the endovascular treatment (EVT) survey. N = 317.

Figure 2.

Average daily hospital census for responding primary stroke centers (PSCs). Y axis is the number of responding hospitals.

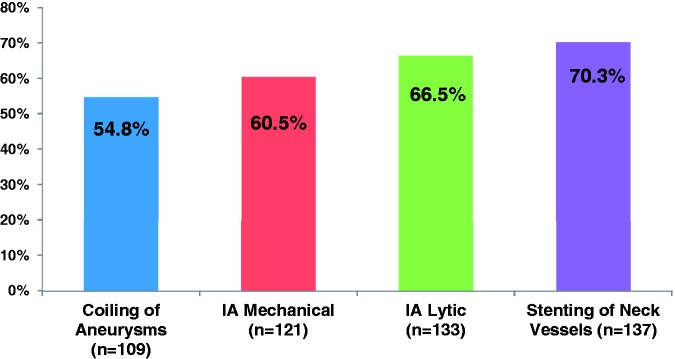

Among the respondents offering EVTs, 95% offered stenting of neck vessels, 86% offered IA lytics, 80% had endovascular mechanical reperfusion techniques for ischemic stroke, and 74% performed coiling of cerebral aneurysms. A slight majority (>55%) of facilities that did offer such services provided them 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and 365 days/year. Such coverage did vary by procedure (see Figure 3), with stenting of neck vessels most often offered 24/7/365 (at 70.3% of responding PSCs), followed by IA lytics (66.5%), IA mechanical reperfusion (60.5%), and coiling of aneurysms (54.8%). There was only one significant difference in EVT service availability between academic and community PSCs, namely IA mechanical interventions, which were available at 84.4% of academic facilities vs 68.1% of community hospitals (p = 0.027).

Figure 3.

Availability of various endovascular treatment (EVT) procedures on a 24/7/365 basis. Y axis is the percentage of responding hospitals offering each procedure. IA: intra-arterial.

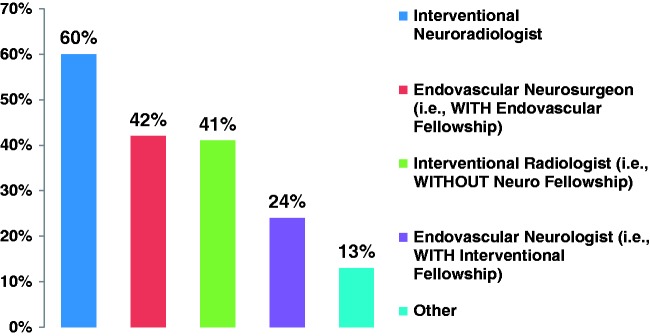

Coverage for EVTs was provided by a variety of specialists with diverse training backgrounds (see Figure 4). Most EVT coverage was provided by interventional neuroradiologists (60%), fellowship-trained endovascular neurosurgeons (42%), and interventional radiologists (41%). Each PSC might have had coverage by a number of different interventionalists with a variety of training backgrounds. About half of treating physicians (53%) cover just one facility, while 22% cover two and 7% cover three (see Figure 5). Different physicians at a specific facility might offer coverage to different numbers of outside facilities depending on their contractual obligations, but we did not collect detailed data in this regard.

Figure 4.

Training of specialists providing endovascular treatment (EVT) services at responding primary stroke centers (PSCs). Numbers are greater than 100% because of multiple training pathways for some respondents.

Figure 5.

Number of hospitals covered by responding physicians performing neuro-interventional procedures.

Most facilities (75%) indicated that they would transfer a patient to a site with endovascular capability if a patient treated with IV TPA at their facility did not show a clinical response. The vast majority of hospitals (81%) did not participate in an audited national registry for EVTs and their outcomes, although 91% of hospitals did indicate that they tracked outcomes locally. Details of how such cases and outcomes were tracked were not collected.

Discussion

This survey study found that among responding PSCs, the majority offer some or most EVTs in either an academic or non-academic setting. There are clearly many patients who require interventional procedures for cerebrovascular disease yet do not have easy access to a CSC because of the small number of such facilities and their uneven distribution.1,14 The fact that a significant proportion of PSCs appear to offer some EVTs might improve patient access to these procedures. The availability of EVT services at some PSCs might also have implications in terms of protocols that promote field triage of patients and by-passing PSCs to reach a CSC.10,15 Such a paradigm might not be appropriate in all circumstances and areas depending on the availability of interventional and support services at a local PSC. Other factors such as local geography, distances, and traffic might further influence triage and diversion decisions.

The availability of EVT services is not required by the JC for certification as a PSC, nor are they required by other certifying agencies or state health departments. Recent trends have shown a significant increase in the use of EVTs for patients with cerebrovascular disease.16 This might be expected to increase even more based on the recently published positive results of the MR CLEAN, ESCAPE, EXTEND-IA, SWIFT-PRIME, and REVASCAT studies of emergent clot removal for patients with acute ischemic large-vessel strokes.5–9 The availability of EVT services also has implications for designing and operating stroke systems of care.10,17

We suspect that some (perhaps many) of the PSCs that offer extensive EVT services are going to become or attempt to become a CSC. Hospitals designated as CSCs are required to offer a variety of EVTs, typically with 24/7/365 coverage.18 In addition, more than a single interventionalist is needed for an organization to be certified by JC as a CSC, since 24/7 coverage cannot be provided by a single person.

Beyond the coverage issue, EVTs cannot be performed in isolation. Typically a multidisciplinary team is required for patient assessment and care before, during, and after such interventions. In many if not most cases the patient would be cared for in a neuroscience intensive care unit (NICU). Cases with complications might require a multidisciplinary care team, including neurosurgeons and neurointensivists in some cases.19 These elements are not present in many PSCs or community hospitals. Since our survey did not collect detailed data about such support services, we are uncertain to what extent they are available in the PSCs offering EVTs.

Our survey found that a variety of specialists were performing EVTs in a number of practice settings. This might in part reflect some flexibility in training requirements and pathways that lead to the expertise and experience needed for a practitioner to perform EVTs. Even with such diversity in specialists who provided EVT services, more than 40% did not offer some or all services on a 24/7/365 basis. Whether this is related to lack of availability of physicians performing EVT or support staff for the interventional suite is unknown.

It was surprising that the vast majority of PSCs that offered EVTs did not participate in an audited registry, although they did track outcomes locally. If such centers performed a small number of EVT procedures, then participating in a national registry would seem to be important to track and compare outcomes. If such centers had larger numbers of patients who underwent EVTs, then contributing to a national registry might affect overall outcomes and be useful for inter-hospital comparisons and benchmarking of results and complications. Tracking outcomes is also important since some medications and devices involved in EVTs are being used off-label.20

There are some potential limitations of our study. We had data only from responding facilities, but our overall response rate was 34%, which is typical if not slightly high for these types of studies. Nonetheless we cannot rule out a response bias in that those facilities that offered EVT services might have been more likely to participate in the survey. In our survey, only 23% of responses were from academic medical centers. Larger surveys of PSCs have found that 30%–60% are academic or teaching hospitals; thus our results may not be representative of all PSCs.21,22

We did not ascertain any data on patient outcomes. A future study might compare characteristics between centers that offer EVT compared to those that do not offer such services. It would have been informative to determine if outcomes for these procedures varied by PSC type, location, or staffing, lastly, the support staff for EVTs is of great importance. The training and experience of the nurses and technicians in the interventional suite can be an important factor in the safety and efficacy of these procedures. Our survey did not include data on these personnel.

In conclusion, our survey found that a variety of important EVT services are offered both in academic and community-based PSCs. These services are typically but not always available 24/7/365. This fact may influence patient triage and EMS protocols for acute stroke patients. Increasing participation in a national registry may be an opportunity to track and validate outcomes. How EVT availability at PSCs will affect the formation and number of CSCs and stroke systems of care is unknown.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions include the following: Mark Alberts: study concept, design, analysis and interpretation of data, writing and revising manuscript, study supervision. Jean Range, V Cantwell, and MJ Hampel: study design, analysis and interpretation of data, revision of manuscript. William Spencer: analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript revision, and statistical analyses.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Mark Alberts—speaker and consultant for Genentech, consultant for Medtronic and The Joint Commission. Jean Range, MJ Hampel, and William Spencer have nothing to declare.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Gorelick PB. Primary and comprehensive stroke centers: History, value and certification criteria. J Stroke 2013; 15: 78–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fonarow GC, Liang L, Smith EE, et al. Comparison of performance achievement award recognition with primary stroke center certification for acute ischemic stroke care. J Am Heart Assoc 2013; 2: e000451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prabhakaran S, McNulty M, O’Neill K, et al. Intravenous thrombolysis for stroke increases over time at primary stroke centers. Stroke 2012; 43: 875–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson AM, Goldstein LB, Bennett P, et al. Compliance with acute stroke care quality measures in hospitals with and without primary stroke center certification: The North Carolina Stroke Care Collaborative. J Am Heart Assoc 2014; 3: e000423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berkhemer OA, Fransen PS, Beumer D, et al. A randomized trial of intraarterial treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell BC, Mitchell PJ, Kleinig TJ, et al. Endovascular therapy for ischemic stroke with perfusion-imaging selection. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1009–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goyal M, Demchuk AM, Menon BK, et al. Randomized assessment of rapid endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1019–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jovin TG, Chamorro A, Cobo E, et al. Thrombectomy within 8 hours after symptom onset in ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 2296–2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saver JL, Goyal M, Bonafé A, et al. Stent-retriever thrombectomy after intravenous t-PA vs. t-PA alone in stroke. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 2285–2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Powers WJ, Derdeyn CP, Biller J, et al. 2015 American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Focused Update of the 2013 Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke Regarding Endovascular Treatment: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2015; 46: 3020–3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alberts M, Hampel M, Cantwell V, et al. Hospital characteristics, distribution, and site reviews of certified comprehensive stroke centers. International Stroke Conference, 2015, Nashville, TN, p.100.

- 12.Choi JH, Bateman BT, Mangla S, et al. Endovascular recanalization therapy in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2006; 37: 419–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanossian N, Liebeskind DS, Eckstein M, et al. Routing ambulances to designated centers increases access to stroke center care and enrollment in prehospital research. Stroke 2015; 46: 2886–2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zaidat OO, Lazzaro M, McGinley E, et al. Demand-supply of neurointerventionalists for endovascular ischemic stroke therapy. Neurology 2012; 79(13 Suppl 1): S35–S41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higashida R, Alberts MJ, Alexander DN, et al. Interactions within stroke systems of care: A policy statement from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2013; 44: 2961–2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hassan AE, Chaudhry SA, Grigoryan M, et al. National trends in utilization and outcomes of endovascular treatment of acute ischemic stroke patients in the mechanical thrombectomy era. Stroke 2012; 43: 3012–3017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith EE, Schwamm LH. Endovascular clot retrieval therapy: Implications for the organization of stroke systems of care in North America. Stroke 2015; 46: 1462–1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alberts MJ, Latchaw RE, Selman WR, et al. Recommendations for comprehensive stroke centers: A consensus statement from the Brain Attack Coalition. Stroke 2005; 36: 1597–1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Varelas PN, Schultz L, Conti M, et al. The impact of a neuro-intensivist on patients with stroke admitted to a neurosciences intensive care unit. Neurocrit Care 2008; 9: 293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdihalim MM, Hassan AE, Qureshi AI. Off-label use of drugs and devices in the neuroendovascular suite. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2013; 34: 2054–2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lichtman JH, Allen NB, Wang Y, et al. Stroke patient outcomes in US hospitals before the start of the Joint Commission Primary Stroke Center certification program. Stroke 2009; 40: 3574–3579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mullen MT, Kasner SE, Kallan MJ, et al. Joint commission primary stroke centers utilize more rt-PA in the nationwide inpatient sample. J Am Heart Assoc 2013; 2: e000071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]