Abstract

Purpose

To compare on-road driving performance of patients with moderate or advanced glaucoma to controls and evaluate factors associated with unsafe driving.

Design

Case-control pilot study.

Methods

A consecutive sample of 21 patients with bilateral moderate or advanced glaucoma from Washington University, St. Louis, MO and 38 community-dwelling controls were enrolled. Participants, ages 55–90 years, underwent a comprehensive clinical evaluation by a trained occupational therapist and an on-road driving evaluation by a masked driver rehabilitation specialist. Overall driving performance of pass vs. marginal/fail and number of wheel and/or brake interventions were recorded.

Results

Fifty-two percent of glaucoma participants scored a marginal/fail compared to 21% of controls (odds ratio [OR], 4.1; 95% CI, 1.30–13.14;p=.02). Glaucoma participants had a higher risk of wheel interventions than controls (OR, 4.67; 95% CI, 1.03–21.17;p=.046). There were no differences detected between glaucoma participants who scored a pass vs. marginal/fail for visual field mean deviation of the better (p=.62) or worse (p=.88) eye, binocular distance (p=.15) or near (p=.23) visual acuity, contrast sensitivity (p=.28) or glare (p=.88). However, glaucoma participants with a marginal/fail score performed worse on Trail Making Tests A (p=.03) and B (p=.05), right-sided Jamar grip strength (p=.02), Rapid Pace Walk (p=.03), Braking Response Time (p=.03), and identifying traffic signs (p=.05).

Conclusions and Relevance

Patients with bilateral moderate or advanced glaucoma are at risk for unsafe driving – particularly those with impairments on psychometric and mobility tests. A comprehensive clinical assessment and on-road driving evaluation is recommended to effectively evaluate driving safety of these patients.

Introduction

Glaucoma patients, particularly those with more advanced disease, have a greater risk of a motor vehicle collision1–4 and being at fault or injured in a motor vehicle collision1,2 than drivers without glaucoma. Many of these unsafe drivers pass state licensing examinations and continue to drive, possibly posing a significant public health risk and financial burden to society and themselves. Conversely, potentially safe drivers with glaucoma not meeting the state-mandated vision requirements for driving may be forced to relinquish their license and unduly suffer from the negative sequelae of driving cessation.5–7 A better understanding of factors associated with driving safety in glaucoma patients, particularly those with more advanced disease, is clearly needed.

An on-road driving assessment provides a valid,8–10 objective, and standardized method of assessing driving performance. Although it’s considered the gold standard in driving assessment, relatively few on-road driving studies have been conducted in patients with glaucoma.11–14 To our knowledge, there are no studies that have comprehensively evaluated clinical factors and on-road driving performance in a high-risk sample of patients with bilateral moderate and advanced glaucoma. The purpose of this pilot study is to compare driving performance of patients with moderate or advanced glaucoma to age-matched controls using a validated on-road driving evaluation. This study also investigates the association between a comprehensive panel of vision and non-vision factors and unsafe driving.

Methods

This is a case-control pilot study in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Human Research Protection Office at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri. A written informed consent was obtained from all eligible participants prior to study participation.

Participants

Patients, ages 55–90 years, with bilateral moderate or advanced glaucoma and age-range matched individuals with no ocular disease participated in this study. Glaucoma patients were recruited during their regularly scheduled clinic visits at Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO. Individuals with no ocular disease were recruited from the volunteer database of healthy community-dwelling older adults maintained by Washington University Medical School and community centers and were screened for any major co-morbidities. All participants completed their visits between March 2010 and August 2011.

Patients with glaucoma were determined based on glaucomatous optic nerve cupping and reproducible visual field defects on the Humphrey Visual Field (VF) Analyzer II (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA, USA) equipped with the Swedish Interactive Threshold Algorithm (SITA) obtained within six months of the study. All glaucoma patients were required to have visual field defects in both eyes that met the criteria for the Glaucoma Staging System15 for stage 2 or worse (criteria including mean deviation of −6.01 or lower). Normal participants had no self-reported ocular disease. All study participants were required to be currently driving with a valid drivers license, have a visual acuity of 20/70 or better in at least one eye in compliance with Missouri and Illinois licensure requirements for visual acuity, speak English, and have at least 10 years of driving experience.

Glaucoma patients and controls were excluded if they had a driving evaluation within 12 months prior to the study or co-morbidities or conditions that may affect driving including advanced cardiopulmonary disease, severe orthopedic or neuromuscular impairments, clinically diagnosed dementia, psychiatric illness, substance abuse, use of potentially sedating medications (e.g. narcotics, anxiolytics), visually significant non-glaucomatous ocular conditions (e.g. macular degeneration, cataracts) or neovascular, uveitic, or acute angle closure glaucoma. Visually significant cataracts for the glaucoma patients were based on chart review and defined as the presence of a posterior subcapsular or nuclear sclerotic cataract graded 2 or greater. Glaucoma patients were excluded if they used a low vision driving aid or underwent ocular incisional surgery within 3 months prior to the study visit.

Study eligibility for glaucoma patients was determined by chart review of consecutive patients from selected glaucoma clinics. Potentially eligible patients were approached and, if currently driving, asked to participate. Individuals with no ocular disease (i.e. controls) were contacted by telephone to confirm study eligibility. All potential participants underwent a telephone interview in which they were screened for dementia using the Alzheimer Disease-8 questionnaire16 and Short Blessed Test.17 Patients declining participation for the on-road driving study were asked the reason and later contacted for participation in the questionnaire-only part of the study.

Driving Evaluation

All consenting glaucoma patients and controls completed a comprehensive clinical assessment and an on-road driving evalution based at the DrivingConnections outpatient clinic located in The Rehabilitation Institute of St. Louis at Washington University Medical Center. Clinical assessments were conducted on the same day and just prior to the on-road evaluation.

Clinical Assessments

The clinical assessments took approximately 90 minutes to complete and were administered by a registered occupational therapist who was not masked to the vision status of the participant. The following measures, except for visual field testing, were administered by the occuptional therapist in the DrivingConnections clinic:

Vision

All vision measures were assessed with the participant’s normal corrective lenses. Monocular and binocular distance and near visual acuity (VA) was measured with the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study and Sloane near VA tests, respectively, and recorded with per-letter scoring.18 Contrast sensitivity (CS) and glare testing were measured binocularly with per-letter scoring using the Pelli-Robson CS chart19,20 and the Vector Vision chart, respectively. Visual field tests were conducted by trained ophthalmic technicians in the eye clinic using standard automated perimetry (Humphrey VF 24-2 with SITA standard program). Mean deviation (MD) was used as the main global index of visual field impairment. Two glaucoma participants (n=3 eyes) completed Goldmann VF tests for their most recent visit, therefore, the mean deviation of their last Humphrey VF test (obtained within one year prior to the study visit) was recorded. Two participants (n=2 eyes) were unable to perform a VF test in their worse eye due to poor vision and were assigned a −30 decibel MD value.

Psychometrics

The Short Blessed Test was administered to screen for cognitive impairment and the Clock Drawing Test21 and the Snellgrove Maze Task measured executive function and visuospatial abilities. Additional assessments included the Trail Making Test-A22 (attention, psychomotor speed, and visual scanning) and B (alternating attention and executive function). Two subtests from the DrivingHealth Inventory were administered: Subtest 2 of the Useful Field of View23 (divided visual attention, visual memory, and processing speed) and the Motor-Free Visual Perceptual Test24 (visual closure). For all psychometric tests, except for the Clock Drawing Test, higher scores indicate greater impairment.

Mobility

Standard goniometric techniques were used to measure cervical range of motion. The Jamar grip dynamometer25 measured grip strength for each hand in pounds, averaging the sum of three trials. Motor speed and coordination were evaluated in seconds using the 9-hole Peg Test26 and The Rapid Pace Walk.27 The Braking Response Time Monitor measured brake reaction time of the right lower extremity.

Medical and Driving Questionnaires

Additional assessments included the Geriatric Depression Scale,28 the Epworth Sleepiness Scale,29 a written driving test and road sign recognition test (i.e. sign name and function),30 and the Driving Habits Questionnaire.31 In order to assess the potential effect of familiarity of the driving course on driving performance, participants were grouped as “familiar with driving area” if their zip code of residence was within or adjacent to the zip code of the on-road driving course.

On-road Driving Evaluation

Modified Washington University Road Test

The road test, a modified version of the valid and reliable Washington University Road Test,32 has been utilized in prior studies.33,34 It is a 13-mile on-road driving test conducted in a predetermined area in St. Louis. The course takes approximately 50–60 minutes to complete and consists of 14 right-hand turns, 11 left-hand turns, 33 traffic lights and 10 stop signs in low and high traffic areas. All tests were conducted in the same, standard sedan (Chevy Impala) equipped with dual brakes. Tests were scheduled during weekdays between 11 AM and 4 PM and were not performed in inclement weather such as severe rain, snow, or icy road conditions.

The driving instructor, a certified driver rehabilitation specialist with over 5 years of experience, sat in the passenger seat and provided directional assistance and safety monitoring. The driving evaluator, a driver rehabilitation specialist with over 15 years of experience of on-road driving evaluations, sat in the back seat and rated the participant’s driving performance. The driving evaluator was masked to the participant’s vision status and performance on the clinical assessments while the driving instructor was not masked due to safety precautions. The same driving instructor and evaluator performed all on-road evaluations and were different from the evaluators in the clinic.

Outcome measures

Overall driving performance was scored as pass, marginal, or fail. A pass score indicated no safety concern, a marginal score indicated low to moderate safety concern (e.g. rolling a stop sign), and a fail indicated major safety concern (e.g. failing to yield to a pedestrian). In order to capture at-risk driving we combined participants that received a marginal or fail score into one group (i.e. marginal/fail group). The number of wheel and brake interventions required by the driving instructor to prevent a potentially unsafe situation was also recorded.

Questionnaire-only study

To address potential selection bias in the glaucoma group undergoing the on-road assessment, glaucoma patients declining the on-road study were asked to partake in a questionnaire-only study. Patients agreeing were contacted by phone and completed the Short Blessed Test, Geriatric Depression Scale, and Driving Habits Questionnaire. Demographic data, ocular and systemic co-morbidities and medications were obtained by phone interview and confirmed by medical chart review.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were reported for demographic data, clinical assessments, and driving performance. Comparisons between the control and glaucoma groups were made using Kruskal-Wallis tests for continuous outcomes and chi-square tests for categorical outcomes. Univariate, unadjusted logistic regression models were used to estimate the association between predictors and driving performance. Driving performance was dichotomized as pass or marginal/fail. Odds ratios were used to express the magnitude of the association between predictors and driving performance. Univariate, unadjusted logistic regression models were used to identify potential candidate variables using p< 0.10 as the selection criteria for inclusion in multivariate prediction models. The final regression model for overall driving performance retained variables with an adjusted p-value of <0.05. All data analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3; SAS Inc, Cary, North Carolina.

Results

A total of 132 patients with glaucoma met criteria for study participation through medical chart review. After further interview, 40% (53 of 132) of patients were not currently driving and thus excluded. Of the 79 eligible patients, 73% (n=58) declined or later withdrew from the study due to stated reasons of scheduling issues (n=14), concern of driving environment (n=12), fear of losing license (n=7), lack of interest (n=9), distance from home (n=8), or provided no reason (n=8). Twenty-one glaucoma patients (27% of those eligible) and 38 controls completed both the clinical and on-road driving assessments.

There were no statistically significant differences in baseline demographics between the control and glaucoma groups (Table 1). Compared to controls, the glaucoma group performed significantly worse on contrast sensitivity (p<.001), Snellgrove Maze Task (p=.002), Trail Making Tests A (p=.009) and B (p=.02) and the UFOV (p=.004).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics and Measures of Vision, Psychometrics, Mobility, and Self-reported Questionnaires in Controls and Patients with Bilateral Moderate and Advanced Glaucoma.

| Characteristic | Controls (n = 38) | Glaucoma (n = 21) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 70.2 (8.4) | 71.5 (8.5) | 0.56 |

| Women, % | 47.4 | 28.6 | 0.16 |

| Caucasian, % | 50.0 | 47.6 | 0.86 |

| Married, % | 47.4 | 71.4 | 0.07 |

| Years of education, mean (SD) | 15.0 (3.3) | 14.4 (2.4) | 0.55 |

|

| |||

| Medical | |||

| Number of co-morbidities, mean (SD) | 1.9 (1.4) | 2.2 (1.6) | 0.48 |

| Geriatric Depression Scale, mean (SD) | 0.4 (0.8) | 0.5 (0.8) | 0.77 |

| Epworth Sleepiness Scale, mean (SD) | 5.0 (2.5) | 5.8 (3.6) | 0.42 |

|

| |||

| Vision | |||

| ETDRS Distance Visual Acuity, mean (SD) | |||

| Better Eye | 53.3 (4.7) | 51.4 (6.0) | 0.16 |

| Worse Eye | 43.7 (10.9) | 35.7 (19.6) | 0.22 |

| Binocular | 55.1 (4.8) | 52.4 (6.5) | 0.06 |

| Sloan Near Visual Acuity, mean (SD) | |||

| Better Eye | 64.8 (6.9) | 61.6 (7.1) | 0.08 |

| Worse Eye | 54.7 (12.5) | 46.4 (20.7) | 0.33 |

| Binocular | 64.4 (10.4) | 64.9 (6.6) | 0.95 |

| Binocular Contrast sensitivity, logCS (SD) | 1.7 (0.2) | 1.4 (0.2) | <0.0001 |

| Binocular Glare, Cd/m2 (SD) | 108.1 (54.1) | 98.1 (59.2) | 0.38 |

|

| |||

| Psychometrics | |||

| Short Blessed Test, mean (SD) | 1.8 (2.3) | 2.4 (2.9) | 0.47 |

| Clock Drawing Test, Freund score, mean (SD) | 6.5 (1.0) | 6.3 (0.9) | 0.25 |

| Snellgrove Maze Task completion, mean (SD), s | 35.2 (11.6) | 48.1 (18.9) | 0.002 |

| Trail Making Test A, mean (SD), s | 43.5 (14.6) | 61.9 (27.7) | 0.009 |

| Trail Making Test B, mean (SD), s | 115.4 (51.3) | 160.5 (77.5) | 0.02 |

| Useful Field of View, mean (SD), ms | 180.5 (106.7) | 298.9 (143.1) | 0.004 |

| Motor-Free Visual Perception Test, mean (SD), no. incorrect | 2.2 (1.6) | 2.1 (1.8) | 0.67 |

|

| |||

| Mobility | |||

| Cervical range of motion, mean (SD), degree | |||

| Right | 61.0 (10.5) | 61.2 (7.3) | 0.49 |

| Left | 61.8 (11.5) | 63.0 (7.3) | 0.75 |

| Jamar grip strength, mean (SD), lb | |||

| Right | 56.6 (23.3) | 62.2 (15.9) | 0.28 |

| Left | 54.3 (23.0) | 59.7 (14.6) | 0.26 |

| Nine-Hole Peg Test, mean (SD), s | |||

| Right | 22.7 (3.5) | 24.7 (5.8) | 0.31 |

| Left | 23.4 (2.8) | 24.6 (4.0) | 0.29 |

| Rapid Pace Walk, mean (SD), s | 6.0 (1.5) | 6.4 (1.9) | 0.46 |

| Braking Response Time, mean (SD), s | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.69 |

|

| |||

| Driving Experience and Knowledge | |||

| Familiar with driving area, % | 18.4 | 23.8 | 0.62 |

| Miles driven per day, mean (SD), mi | 23.7 (19.4) | 22.3 (18.8) | 0.72 |

| Written driving test, mean (SD), no. correct | 11.2 (1.7) | 10.9 (1.8) | 0.52 |

| Sign names, mean (SD), no. correct | 9.2 (2.2) | 9.6 (2.3) | 0.38 |

| Sign function, mean (SD), no. correct | 9.6 (2.0) | 9.8 (2.2) | 0.61 |

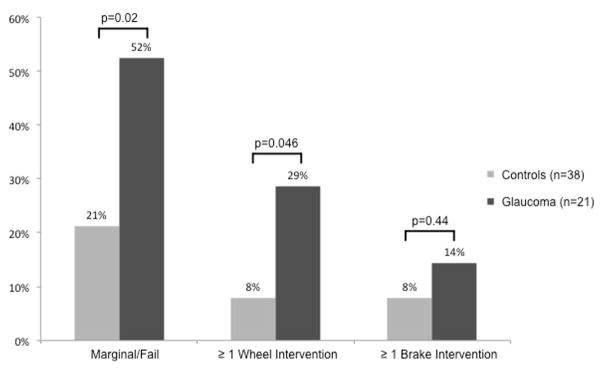

Fifty-two percent (11 of 21) of glaucoma participants received a marginal/fail score on the on-road driving evaluation compared to 21% (8 of 38) of controls (p=.02, Figure 1). Glaucoma participants were 4.13 times more likely to score a marginal/fail than controls (95% CI,1.30–13.14;p=.02). A higher proportion of glaucoma participants required ≥1 wheel intervention compared to controls (29% vs. 8%, p=.03) with a 4.7 times greater risk (95% CI,1.03–21.17;p=.046). Although a higher proportion of glaucoma participants required ≥1 brake intervention compared to controls (14% vs. 8%), no statistically significant difference was detected (Odds Ratio [OR] 1.94;95% CI,0.36–10.63;p=.44).

Figure 1.

Proportion of participants with bilateral moderate and advanced glaucoma and controls receiving a marginal or fail score, requiring ≥1 wheel intervention and requiring ≥1 brake intervention on the on-road driving evaluation.

Table 2 compares baseline characteristics and clinical assessments of participants who passed to those with a margin/fail score. In the total sample, participants with a marginal/fail score were older (OR,3.41 per decade; 95% CI,1.46–7.96;p=.005), more likely to be Caucasian (OR,3.25;95% CI,1.02–10.32;p=.046), have a diagnosis of glaucoma (OR,4.13;95% CI,1.30–13.14;p=.02), and performed worse on contrast sensitivity (OR,0.73 per tenth logCS;95% CI,0.55–0.97;p=.03), Snellgrove Maze Task (OR,1.45 per 10 seconds;95% CI,1.00–2.11;p=.048), Trail Making Tests A (OR,1.82 per 10 seconds;95% CI,1.26–2.62;p=.001) and B (OR,1.26 per 25 seconds;95% CI,1.01–1.56;p=.04), right-sided 9-hole peg test (OR,2.35 per 5 seconds;95% CI,1.12–4.95;p=.02), Rapid Pace Walk (OR,1.46 per second;95% CI,1.00–2.12;p=.048), and recognizing sign functions (OR,0.73;95% CI,0.55–0.96;p=.03). In the final model for the total sample, performance on Trail Making Test A was significantly associated with a marginal/fail score (p=.001). There was a strong correlation between Trails A and contrast sensitivity (r=−0.54, p<0.001), EDTRS (r=−0.47, p=0.0002), and near visual acuity (r=0.29, p=0.02).

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics and Measures of Vision, Psychometrics, Mobility, and Self-reported Questionnaires by Performance on On-Road Driving Evaluation for All Participants and Participants with Bilateral Moderate and Advanced Glaucoma.

| All Participants | Glaucoma Participants | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Characteristic | Pass (n=40) | Marginal/Fail (n=19) | P value | Pass (n=10) | Marginal/Fail (n=11) | P value |

| Demographic | ||||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 68.3 (7.6) | 75.5 (8.0) | 0.005 | 67.2 (5.7) | 75.4 (8.9) | 0.045 |

| Women, % | 37.5 | 47.4 | 0.47 | 10.0 | 45.5 | 0.097 |

| Caucasian, % | 40.0 | 68.4 | 0.046 | 50.0 | 45.5 | 0.84 |

| Married, % | 62.5 | 42.1 | 0.14 | 100.0 | 45.5 | 0.01 |

| Years of education, mean (SD) | 14.8 (3.3) | 14.7 (2.4) | 0.90 | 15.0 (3.0) | 13.9 (1.8) | 0.31 |

|

| ||||||

| Medical | ||||||

| Glaucoma (%) | 25.0 | 57.9 | 0.02 | 100.0 | 100.0 | -- |

| Pseudophakia in at least one eye (%) | -- | -- | -- | 30.0 | 81.8 | 0.02 |

| Co-morbidities, mean (SD), no. | 2.0 (1.3) | 1.9 (1.7) | 0.84 | 2.3 (1.3) | 2.1 (1.9) | 0.76 |

| Geriatric Depression Score, mean (SD) | 0.3 (0.6) | 0.6 (1.1) | 0.29 | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.7 (1.1) | 0.21 |

| Epworth Sleepiness Score, mean (SD) | 5.5 (2.9) | 4.9 (3.0) | 0.48 | 6.1 (3.8) | 5.5 (3.5) | 0.72 |

|

| ||||||

| Vision | ||||||

| ETDRS Distance Visual Acuity, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Better Eye | 53.3 (4.7) | 51.2 (6.2) | 0.15 | 53.6 (5.1) | 49.5 (6.3) | 0.13 |

| Worse Eye | 42.3 (13.4) | 38.0 (17.8) | 0.31 | 39.0 (19.3) | 32.7 (20.3) | 0.46 |

| Binocular | 54.9 (5.4) | 52.4 (5.6) | 0.11 | 54.7 (6.6) | 50.4 (6.0) | 0.15 |

| Sloan Near Visual Acuity, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Better Eye | 63.8 (7.2) | 63.5 (7.0) | 0.89 | 60.7 (7.0) | 62.5 (7.5) | 0.57 |

| Worse Eye | 53.4 (14.4) | 48.3 (19.6) | 0.27 | 49.4 (16.9) | 43.7 (24.1) | 0.52 |

| Binocular | 64.7 (10.1) | 64.2 (7.0) | 0.82 | 66.7 (4.8) | 63.2 (7.6) | 0.23 |

| Binocular Contrast sensitivity, logCS (SD) | 1.7 (0.2) | 1.5 (0.3) | 0.03 | 1.5 (0.2) | 1.4 (0.2) | 0.28 |

| Binocular Glare, Cd/m2 (SD) | 111.8 (52.1) | 89.3 (61.2) | 0.15 | 100.2 (49.8) | 96.3 (69.1) | 0.88 |

| Humphrey Visual Field Mean Deviation, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Better Eye | -- | -- | -- | −12.1 (5.7) | −13.4 (6.7) | 0.62 |

| Worse Eye | -- | -- | -- | −21.2 (5.1) | −21.6 (5.5) | 0.88 |

|

| ||||||

| Psychometrics | ||||||

| Short Blessed Test, mean (SD) | 1.9 (2.7) | 2.4 (2.3) | 0.29 | 1.9 (3.3) | 2.9 (2.4) | 0.42 |

| Clock Drawing Test, Freund score, mean (SD) | 6.5 (0.8) | 6.3 (1.2) | 0.38 | 6.5 (0.5) | 6.2 (1.2) | 0.44 |

| Snellgrove Maze Task completion, mean (SD), s | 36.8 (12.3) | 46.0 (20.3) | 0.048 | 39.2 (12.2) | 56.2 (20.6) | 0.07 |

| Trail Making Test A, mean (SD), s | 42.5 (12.5) | 65.8 (28.6) | 0.001 | 41.8 (10.6) | 80.1 (25.8) | 0.03 |

| Trail Making Test B, mean (SD), s | 119.0 (48.6) | 157.7 (86.1) | 0.04 | 122.5 (42.4) | 195.1 (87.3) | 0.051 |

| Useful Field of View, mean (SD), ms | 206.0 (124.2) | 273.9 (148.4) | 0.10 | 259.0 (148.4) | 338.8 (133.0) | 0.21 |

| Motor-Free Visual Perception Test, no. incorrect, mean (SD) | 2.3 (1.8) | 1.6 (1.1) | 0.16 | 2.3 (2.3) | 1.8 (1.1) | 0.52 |

|

| ||||||

| Mobility | ||||||

| Cervical range of motion, mean (SD), degree | ||||||

| Right | 61.4 (9.2) | 60.4 (10.0) | 0.69 | 60.3 (5.6) | 62.0 (8.8) | 0.59 |

| Left | 62.1 (10.8) | 62.6 (9.0) | 0.86 | 63.3 (8.2) | 62.7 (6.9) | 0.86 |

| Jamar grip strength, mean (SD), lb | ||||||

| Right | 62.2 (21.5) | 50.9 (18.0) | 0.06 | 73.0 (9.5) | 52.3 (14.2) | 0.02 |

| Left | 58.2 (21.2) | 52.0 (18.5) | 0.28 | 66.0 (11.7) | 53.9 (15.0) | 0.08 |

| Nine-Hole Peg Test, mean (SD), s | ||||||

| Right | 22.4 (3.6) | 25.6 (5.6) | 0.02 | 22.2 (4.4) | 27.0 (6.2) | 0.09 |

| Left | 23.5 (2.8) | 24.6 (4.1) | 0.24 | 23.4 (3.1) | 25.7 (4.5) | 0.21 |

| Rapid Pace Walk, mean (SD), s | 5.8 (1.5) | 6.8 (1.8) | 0.048 | 5.3 (1.3) | 7.4 (1.8) | 0.03 |

| Braking Response Time, mean (SD), s | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.07 | 0.5 (0.1) | 0.7 (0.1) | 0.03 |

|

| ||||||

| Driving Experience and Knowledge | ||||||

| Familiar with driving area, % | 22.5 | 15.8 | 0.55 | 30.0 | 18.2 | 0.53 |

| Miles driven per day, mean (SD), min; | 26.3 (21.9) | 16.9 (9.0) | 0.09 | 28.7 (25.1) | 17.0 (10.0) | 0.19 |

| Written driving test, mean (SD), no. correct | 11.3 (1.6) | 10.6 (1.8) | 0.17 | 11.5 (1.6) | 10.3 (1.8) | 0.13 |

| Sign names, mean (SD), no. correct | 9.7 (2.0) | 8.6 (2.4) | 0.07 | 10.8 (1.0) | 8.5 (2.6) | 0.048 |

| Sign function, mean (SD), no. correct | 10.1 (1.8) | 8.8 (2.3) | 0.03 | 10.9 (1.3) | 8.7 (2.5) | 0.06 |

In the glaucoma group, participants with a marginal/fail score were older (OR,4.55 per decade;95% CI,1.03–20.04;p=.045), less likely to be married (OR,24.82;95% CI,1.17–527.10;p=.01), more likely to be pseudophakic in at least one eye (OR,10.50;95%CI,1.36–81.05;p=.02), and performed worse on Trail Making Test A (OR,4.43 per 10 seconds;95% CI,1.12–17.57;p=0.03), right-sided Jamar grip strength(OR,0.23 per 10 pounds;95% CI, 0.07–0.75;p=.02), Rapid Pace Walk (OR,2.69 per second;95% CI,1.13–6.42;p=.03), Brake Response Time (OR,10.95 per tenth of a second;95% CI,1.24–96.66;p=.03), and identifying traffic sign names (OR,0.52;95% CI,0.27–0.99;p=.048). There were no differences detected between glaucoma participants who passed vs. marginal/fail for mean deviation on VF tests in the better eye (i.e. less visual field loss) (OR,1.04 per −1 decibels;95% CI,0.90–1.20;p=.62) or worse eye (OR,1.01 per −1 decibel;95% CI, 0.85–1.20;p=.88), binocular distance visual acuity (OR,0.53 per 5 letters;95% CI,0.23–1.26;p=.15), near visual acuity (OR,0.61 per 5 letters; 95% CI,0.27–1.38;p=0.23), contrast sensitivity (OR,0.77 per tenth logCS;95% CI,0.48–1.24;p=.28), or glare (OR,0.94 per 50 Cd/M2; 95% CI,0.45–1.98;p=.88) testing. In the final model for the glaucoma group, Trail Making Test A was the only predictor significantly associated with a marginal/fail score (p=.03).

In the normal group, participants with a marginal/fail score (n=8 of 38) were slightly older (p=.051) and more likely to be Caucasian (p=.003) than those that passed (n=30 of 38) the on-road driving evaluation. There were no statistically significant differences in clinical assessments between normals who passed and those with a marginal/fail score.

Of the 58 eligible glaucoma patients declining the on-road driving evaluation, 23 (40%) completed the questionnaire-only study. Compared to the on-road driving group, the questionnaire-only group scored higher for depressive symptoms (p=.001). There were no differences between the 2 groups for age (p=.92), gender (p=.19), race (p=.07), education (p=.86), Short Blessed Test score (p=.39), pseudophakic status (p=.39), mean deviation of VF test in the better (p=.77) or worse (p=.52) eye, number of days (p=.08) or miles (p=.18) driven per week or accidents over the past year (p=.16).

Discussion

This study comprehensively evaluated a sample at high risk for driving safety –patients with bilateral moderate or advanced glaucoma. Glaucoma patients performed worse, overall, compared to controls on the on-road driving evaluation. Patients at greatest risk for unsafe driving were those with slower performance on psychometric and mobility testing.

In our pilot study, moderate/advanced glaucoma patients had a 4.1× greater risk of unsafe driving (i.e. marginal or fail score) and a 4.7× greater risk of requiring a wheel intervention compared to controls. These results were only slightly higher than the 3.6× increased risk of a reported motor vehicle collision for glaucoma patients with severe visual field defects (in worse eye) compared to no defects.4 A prior on-road driving study, however, found that glaucoma patients (n=20) had no difference in overall driving performance compared to controls (n=20) but a 6× increased risk of a wheel/brake intervention.11 These results may differ from ours due to a milder glaucoma severity in their sample (−1.7 vs. −12.7 decibels, better eye) and differences in overall scoring criteria and thresholds for a wheel/brake intervention.

The glaucoma sample in our study had a higher risk of unsafe driving compared to controls, however, there were baseline differences between the two groups on certain psychometric tests (Snellgrove Maze Task, Trail Making Tests A and B, and Useful Field of View). It is possible that slower performance on these tests by the glaucoma group may be due to early cognitive impairment. However, we believe that slower performance by the glaucoma group on these vision-dependent tests may be due to their vision impairment, and not early cognitive decline. The lack of a significant difference between the glaucoma and control groups for the vision-independent cognitive test (Short Blessed Test) supports this theory. In a prior study, visually impaired patients performed successfully, yet slower, on psychometric tests compared to normal-sighted individuals.35 A visual acuity of even 20/40 affected performance on nonverbal tests.36 Slower reading has been reported in glaucoma patients,37,38 thus slower performance on certain psychometric tests may be due to poor vision and not cognitive impairment. Future studies would benefit from a more in-depth clinical evaluation using the Clinical Dementia Rating, Montreal Cognitive Assessment and non-vision dependent cognitive tests to better screen for cognitive impairment in glaucoma patients.

The only significant predictor detected for unsafe driving on multivariate analysis was performance on Trail Making Test A, and not a diagnosis of glaucoma. One plausible explanation for the analysis with the entire sample is that glaucoma was represented by a dichotomous variable (glaucoma vs. no glaucoma) as opposed to a preferable continuous variable (i.e. mean deviation on visual field testing) as is Trail Making Test A. This was due to the lack of VF testing in the control group. Interestingly, there was a strong correlation between Trail Making Test A and vision tests with continuous variables (contrast sensitivity, distance and near visual acuity) suggesting a possible confounding effect between Trail Making Test A and vision measures that may be associated with glaucoma. Within the glaucoma group, there were no significant differences detected in vision tests, including visual field mean deviation, between safe and unsafe drivers. This may be due to the truncated range of vision and visual field defects in this sample of patients with more advanced disease. A larger study which incudes patients with mild glaucoma as well as controls undergoing VF testing may help clarify associations between vision factors and driving performance.

While the glaucoma group performed overall worse on the driving evaluation than controls, glaucoma is likely not the only risk factor affecting driving. Increased age, Caucasian race, and poor performance on contrast sensitivity and certain psychometric and mobility tests were also associated with unsafe driving. Furthermore, in our glaucoma sample, worse driving performance occurred in patients with additional impairments in psychometric and mobility testing. It is possible that a diagnosis of glaucoma in combination with increased age and impairments in cognition, mobility, and likely other factors, impact the ability to drive safely.

An unexpected result of our study was that approximately half of the moderate/advanced glaucoma group passed the on-road test with no major driving concerns. These safe drivers, who performed better on psychometric and mobility tests than similar-sighted unsafe drivers, may be using strategies to compensate for their vision impairment while driving. Compensatory driving strategies such as saccadic eye movements and head movements have been associated with safer driving in patients with visual field loss.12,14,39 Further knowledge of compensatory strategies used by safe drivers with glaucoma can be used to improve driving safety for patients who are currently driving and enable some patients with glaucoma who are not driving (i.e. 40% in our study) the opportunity to continue to drive safely.

Limitations of this study are those inherent to on-road driving studies and include variations in traffic and weather between participants, the presence of two evaluators in an unfamiliar car, and potential fatigue for the on-road test after the 90-minute clinical assessment. In addition, glaucoma patients often restrict their driving,40 thus study results may not reflect a patient’s driving in their normal driving environment. While these factors may affect driving, on-road testing has been found to be a good proxy to naturalistic driving.10 Due to safety precautions, the driving instructor (in the front seat) was not masked to the vision status of the driver, potentially inducing a measurement bias for wheel and brake interventions. Normal controls had self-reported ocular conditions and did not undergo visual field testing to confirm an absence of a glaucoma diagnosis. A potential selection bias may have occurred for glaucoma patients who are safe drivers. However, in our comparison of patients completing the on-road driving evaluation to those who declined (i.e. questionnaire-only group) there were no differences detected for demographics, glaucoma severity, Short Blessed test, driving experience, or number of motor vehicle collisions - suggesting a low likelihood of selection bias. Lastly, the results of this study may not necessarily be generalizable to patients with other significant co-morbidities or vision disorders that further affect driving risk.

This study was able to overcome multiple challenges to successfully recruit patients with bilateral moderate/advanced glaucoma to complete a comprehensive on-road driving evaluation. Additional strengths include the validated on-road driving evaluation, the masking of the driving evaluator (in the back seat) to the vision status of the participant, the control group for comparative analysis, and the questionnaire-only group to evaluate potential selection bias.

Patients with moderate or advanced glaucoma are at risk for unsafe driving – particularly those with slower performance on psychometric and mobility tests. Some glaucoma patients, however, may be safe drivers. In order to effectively evaluate driving safety, select glaucoma patients should undergo a multifaceted exam including a comprehensive clinical and on-road driving assessment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support:

This work was supported by awards from the Missouri Department of Transportation Traffic and Highway Safety Division, Jefferson City, Missouri; National Eye Institute, Bethesda, Maryland (1K23EY017616-01): American Glaucoma Society, San Francisco, California; Grace Nelson Lacey Grant, St. Louis, Missouri; donations from the Schnuck and Wolff foundations, St. Louis, Missouri; unrestricted grants from Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, New York; National Institutes of Health Vision Core Grant P30 EY02687, Bethesda, Maryland; and the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grants UL1 TR000448 and TL1 TR000449 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland. The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Other Acknowledgements:

The authors thank Ann M. Johnson, Kathy Dolan OTR/L (The Rehabilitation Institute of St. Louis) and Steven Ice MOT, OTR/L, CDRS (Independent Drivers, LLC) for their assistance in patient recruitment and driving evaluations, Jenna Kim and Harrison Gammon for assistance in data collection, and Dr. Carol Snellgrove for use of the Snellgrove Maze Task. Drs. Anjali Bhorade and Mae Gordon had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Funding Disclosures:

Dr. Bhorade has no additional disclosures outside the submitted work. Dr. Yom reports no financial disclosures in medicine. Dr. Barco reports funding from the Missouri Department of Transportation during the conduct of the study. Mr. Wilson reports no financial disclosures in medicine. Dr. Gordon reports no additional disclosures. Dr. Carr reports funding from the National Institute of Health, Missouri Department of Transportation, Traffic Injury Research Foundation, Medscape, American Automotive Association Foundation Traffic Safety and State Farm Insurance.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Haymes SA, Leblanc RP, Nicolela MT, Chiasson LA, Chauhan BC. Risk of falls and motor vehicle collisions in glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(3):1149–1155. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Owsley C, McGwin G, Jr, Ball K. Vision impairment, eye disease, and injurious motor vehicle crashes in the elderly. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 1998;5(2):101–113. doi: 10.1076/opep.5.2.101.1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Owsley C, McGwin G, Searcey K. A Population-Based Examination of the Visual and Ophthalmological Characteristics of Licensed Drivers Aged 70 and Older. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(5):567–573. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGwin G, Jr, Xie A, Mays A, et al. Visual field defects and the risk of motor vehicle collisions among patients with glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(12):4437–4441. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marottoli RA, Mendes de Leon CF, Glass TA, et al. Driving cessation and increased depressive symptoms: prospective evidence from the New Haven EPESE. Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45(2):202–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb04508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Owsley C, McGwin G, Scilley K, Girkin CA, Phillips JM, Searcey K. Perceived barriers to care and attitudes about vision and eye care: focus groups with older African Americans and eye care providers. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(7):2797–2802. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freeman EE, Gange SJ, Muñoz B, West SK. Driving status and risk of entry into long-term care in older adults. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(7):1254–1259. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.069146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emerson JL, Johnson AM, Dawson JD, Uc EY, Anderson SW, Rizzo M. Predictors of driving outcomes in advancing age. Psychol Aging. 2012;27(3):550–559. doi: 10.1037/a0026359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Classen S, Shechtman O, Awadzi KD, Joo Y, Lanford DN. Traffic violations versus driving errors of older adults: informing clinical practice. Am J Occup Ther. 2010;64(2):233–241. doi: 10.5014/ajot.64.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis JD, Papandonatos GD, Miller LA, et al. Road test and naturalistic driving performance in healthy and cognitively impaired older adults: does environment matter? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(11):2056–2062. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04206.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haymes SA, Leblanc RP, Nicolela MT, Chiasson LA, Chauhan BC. Glaucoma and on-road driving performance. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49(7):3035–3041. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coeckelbergh TM, Brouwer WH, Cornelissen FW, van Wolffelaar P, Kooijman AC. The effect of visual field defects on driving performance: A driving simulator study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120(11):1509–1516. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.11.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bowers A, Peli ELI, Elgin JOL, McGwin GJMS, Owsley CM. On-Road Driving with Moderate Visual Field Loss. Optom & Vis. 2005;82(8):657–667. doi: 10.1097/01.opx.0000175558.33268.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kasneci E, Sippel K, Aehling K, et al. Driving with binocular visual field loss? A study on a supervised on-road parcours with simultaneous eye and head tracking. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e87470. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mills RP, Budenz DL, Lee PP, et al. Categorizing the Stage of Glaucoma From Pre-Diagnosis to End-Stage Disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141(1):24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galvin JE, Roe CM, Powlishta KK, et al. The AD8: a brief informant interview to detect dementia. Neurology. 2005;65(4):559–564. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000172958.95282.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P, Peck A, Schechter R, Schimmel H. Validation of a short Orientation-Memory-Concentration Test of cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140(6):734–739. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.6.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferris FL, Kassoff A, Bresnick GH, Bailey I. New visual acuity charts for clinical research. Am J Ophthalmol. 1982;94(1):91–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pelli DG, Robson JG, Wilkins AJ. The Design of a New Letter Chart for Measuring Contrast Sensitivity. Clin Vision Sci. 1988;2(3):187–199. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elliott D, Bullimore M, Bailey I. Improving the reliability of the Pelli-Robson contrast sensitivity test. Clin Vision Sci. 1991;6:471–475. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freund B, Gravenstein S, Ferris R, Burke BL, Shaheen E. Drawing clocks and driving cars. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(3):240–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40069.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reitan R. Validity of the Trail Making Test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Percept Mot Skills. 1958;(8):271–276. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ball K. Attentional problems and older drivers. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1997;11(Suppl 1):42–47. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199706001-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Staplin L, Gish KW, Wagner EK. MaryPODS revisited: Updated crash analysis and implications for screening program implementation. J Safety Res. 2003;34:389–397. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bohannon RW, Peolsson A, Massy-Westropp N, Desrosiers J, Bear-Lehman JB. Reference values for adult grip strength measured with a Jamar dynamometer: A descriptive meta-analysis. Physiotherapy. 2006;(92):11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oxford GK, Vogel KA, Le V, Mitchell A, Muniz S, Vollmer MA. Adult norms for a commercially available Nine Hole Peg Test for finger dexterity. Am J Occup Ther. 2003;(57):570–573. doi: 10.5014/ajot.57.5.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ball KK, Roenker DL, Wadley VG, et al. Can High-Risk Older Drivers Be Identified Through Performance-Based Measures in a Department of Motor Vehicles Setting? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(1):77–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoyl MT, Alessi CA, Harker JO, et al. Development and testing of a five-item version of the Geriatric Depression Scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(7):873–878. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb03848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14(6):540–545. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carr DB, LaBarge E, Dunnigan K, Storandt M. Differentiating Drivers With Dementia of the Alzheimer Type From Healthy Older Persons With a Traffic Sign Naming Test. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1998;53A(2):M135–M139. doi: 10.1093/gerona/53a.2.m135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Owsley C, Stalvey B, Wells J, Sloane ME. Older Drivers and Cataract: Driving Habits and Crash Risk. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54(4):M203–M211. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.4.m203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hunt LA, Murphy CF, Carr D, Duchek JM, Buckles V, Morris JC. Environmental cueing may effect performance on a road test for drivers with dementia of the Alzheimer type. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1997;11(Suppl 1):13–16. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199706001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carr DB, Barco PP, Wallendorf MJ, Snellgrove CA, Ott BR. Predicting road test performance in drivers with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(11):2112–2117. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03657.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barco PP, Wallendorf MJ, Snellgrove CA, Ott BR, Carr DB. Predicting road test performance in drivers with stroke. Am J Occup Ther. 2014;68(2):221–229. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2014.008938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hunt LA, Bassi CJ. Near-vision acuity levels and performance on neuropsychological assessments used in occupational therapy. Am J Occup Ther. 2010;64(1):105–113. doi: 10.5014/ajot.64.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bertone A, Bettinelli L, Faubert J. The impact of blurred vision on cognitive assessment. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2007;29(5):467–476. doi: 10.1080/13803390600770793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramulu PY, Swenor BK, Jefferys JL, Friedman DS, Rubin GS. Difficulty with out-loud and silent reading in glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(1):666–672. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mathews PM, Rubin GS, McCloskey M, Salek S, Ramulu PY. Severity of vision loss interacts with word-specific features to impact out-loud reading in glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(3):1537–1545. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-15462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wood JM, McGwin GJ, Elgin J, et al. Hemianopic and quadrantanopic field loss, eye and head movements, and driving. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(3) doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Landingham SW, Hochberg C, Massof RW, Chan E, Friedman DS, Ramulu PY. Driving patterns in older adults with glaucoma. BMC Ophthalmol. 2013;13:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-13-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.