Abstract

Importance

Recent studies found that the concentration of amyloid-β (Aβ) fluctuates with the sleep-wake cycle. Although the amplitude of this day/night pattern attenuates with age and amyloid deposition, the relationship of Aβ kinetics (production, turnover, and clearance) to this oscillation has not been studied.

Objective

To determine the relationships between Aβ kinetics, age, amyloid, and the Aβ day/night pattern in humans, we measured Aβ concentrations and kinetics in 77 adults 60-87 years old by a novel precise mass spectrometry (MS) method.

Design

We compared findings of two orthogonal methods, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and MS, to validate the day/night patterns and determine more precise estimates of the cosinor parameters. In vivo labeling of central nervous system (CNS) proteins with stable isotopically labeled leucine was performed and kinetics of Aβ40 and Aβ42 measured.

Setting

Washington University School of Medicine in St Louis, Missouri.

Participants

Participants sixty years old or greater without and with amyloid deposition.

Interventions

Serial CSF collection via indwelling lumbar catheter over 36-48 hours before, during, and after in vivo labeling with a 9-hour primed constant infusion of 13C6-leucine.

Main outcome and measures

We determined the amplitude, linear increase, and other cosinor measures of each participants' serial CSF Aβ concentrations and Aβ turnover rates.

Results

Day/night patterns in Aβ concentrations were more sharply defined by the precise MS method than by ELISA. Amyloid deposition diminished Aβ42 day/night amplitude and linear increase, but not Aβ40. Increased age diminished both Aβ40 and Aβ42 day/night amplitude. After controlling for amyloid deposition, Aβ40 amplitude positively correlated with production rates, while the linear rise correlated with turnover rates. Aβ42 amplitude and linear rise were both correlated with turnover and production rates.

Conclusion and Relevance

Amyloid deposition is associated with premature loss of normal Aβ42day/night patterns in aging suggesting the previously reported effects of age and amyloid on Aβ42 amplitude at least partially affect each other. Production and turnover rates suggest that day/night Aβ patterns are modulated by both production and clearance mechanisms active in sleep-wake cycles and amyloid deposition may impair normal circadian patterns. These findings may have importance in Alzheimer's disease secondary prevention trial design.

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized pathologically by the extracellular deposition of amyloid-β (Aβ) in senile plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles of tau leading to neuronal loss and progressive cognitive impairment. AD represents a current and growing public health threat with the worldwide prevalence of the disease projected to increase from 46.8 million people in 2015 to 131.5 million in 2050 (1). Age and Aβ deposition are major risk factors for AD. Age slows the half-life and clearance of soluble Aβ while Aβ deposition causes irreversible loss of soluble Aβ42 clearance (2). Since aggregation and deposition of Aβ into insoluble extracellular plaques is concentration-dependent (3), factors that affect Aβ concentration through changes in production and clearance are potential therapeutic targets for AD prevention.

Recent studies in animal models and humans have found that 1) the concentration of central nervous system (CNS) Aβ fluctuates with the sleep-wake cycle as a day/night (i.e. diurnal) pattern, 2) the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) Aβ concentration increases linearly with serial sampling which is mitigated with amyloid deposition, and 3) the amplitude of this day/night pattern attenuates with age and amyloid deposition (4-6). The findings of the diurnal pattern and linear increases of Aβ in human CSF have been replicated across multiple studies (7). Decreased Aβ production and increased clearance during sleep have been hypothesized to drive the day/night oscillation (8, 9). Sleep has been linked to a mechanistic ‘flushing’ of extracellular components such as Aβ that appears to be a normal ‘glymphatic’ clearance mechanism (9, 10). The relationship of sleep, the day/night pattern, and clearance of Aβ (potentially by this glymphatic system) is not well-understood. In this study, we assessed the relationships between Aβ production, clearance, day/night patterns, and the linear rise as it relates to normal and abnormal Aβ production and clearance mechanisms. These findings will inform the design of future studies, and may lead to approaches to maintain normal physiological control of Aβ concentrations through sleep-mediated changes in the day/night pattern.

Methods

Participants

Seventy-seven participants serving as research volunteers in the longitudinal studies of the Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center (ADRC) and its affiliated studies at Washington University were recruited to participate in this study. These 77 individuals ranged in age from 60 to 87 years; 46 were men (mean 72.6 years, aged 60.4 to 87.7) and 31 were women (mean 72.6 years, aged 63.8 to 85.2). All 77 participants were assessed clinically with a standard protocol that includes the Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB) score that ranges from 0 (no impairment) to 18 (maximal impairment) (11, 12). Thirty-three participants had a CDR-SB of 0 and forty-four participants had a CDR-SB >0. Participant demographics are shown in eTable 1. The study protocol was approved by the Washington University Institutional Review Board and the General Clinical Research Center Advisory Committee. All participants completed written informed consent and were compensated for their participation in the study.

Determining Amyloid Status

Amyloid status was established for each participant as previous described (2). For the 44 participants with PET [11C]PIB (PET: Positron Emission Tomography; PIB: Pittsburgh Compound B) scans, amyloid deposition (amyloid-positive) was established if the mean cortical binding potential (MCBP) was >0.18 (13). For the 33 participants without PET PIB scans, a CSF [Aβ42]: [Aβ40] ratio <0.12 defined amyloid-positive.

Aβ Concentration

Previous studies of the Aβ concentrations measured in day/night patterns used Aβ concentrations determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), which has a relatively high variance of measurement (typical %CV of 10 to 20%). Recent advances in mass spectrometry (MS) allow for the precise simultaneous quantitation of CSF Aβ isoform concentrations and Aβ stable isotope labeling kinetics (SILK).

From each time point collected, Aβ40 and Aβ42 were measured using ELISA as previously described (5). All samples from each participant were measured together on the same ELISA plate to avoid interplate variation and each sample was assessed in duplicate. MS Aβ SILK and absolute quantitation of Aβ were performed simultaneously. All samples were processed and measured as previously described (2, 14).

Aβ SILK

The procedure for stable isotope amino acid tracer administration, sample collection, Aβ SILK tracer protocol, and compartmental modeling analysis of Aβ kinetics for all 77 participants were previously reported (2, 15). Analysis of Aβ SILK kinetics generated three key measures of Aβ kinetics representing the fractional turnover rates (directly related to the half-life), absolute production rates, and an exchange process or delay component.

Cosinor Analysis

Cosinor analysis was used to fit a cosine wave to each individual's serial CSFAβ values measured by both ELISA and MS; as previously described, a 24-hour period was set as the default circadian cycle(7). The y-intercept (equivalent to the mesor or midline of the Aβ oscillation), amplitude (distance between the peak and mesor), acrophase (time corresponding to the peak of the curve), and slope of the linear rise were calculated for each participant.

Comparison of Cosinor Analysis Between ELISA and MS

To measure the uncertainty of cosine fit between the ELISA and MS measurements, we converted all 77 participants' serial CSF Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations to percent of the mean to control for differences between the assays. The data transformation was calculated separately for Aβ40 and Aβ42. Then, we calculated the standard deviation of the residuals (SDR) for each cosine fit to determine how well the fitted cosine wave compared between ELISA and MS data. Cosinor analysis determines the curve that minimizes the sum of squares of the distances between individual data points and the best-fit line. SDR is equal to the square root of the sum of squares divided by degrees of freedom and is expressed in the same units as Y (i.e. percent of the mean). Degrees of freedom in this case equals the number of data points minus the number of parameters fit. The greater the SDR, the greater the uncertainty of the true best-fit curve. Cosine fit SDRs was also compared to the SDRs of a straight-line fit.

Statistics

SPSS v. 23 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. Graphpad Prism version 6.0b for Mac (Graphpad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to calculate the parameters of the cosinor analysis for Aβ40 and Aβ42. Statistical significant was set at p<0.05.

Results

Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations measured by MS and ELISA for all 77 participants were transformed to percent of the mean. The average correlation coefficients between MS and ELISA for both isoforms were 0.3. Serial Aβ concentrations were fitted to a straight-line and a cosine wave. Cosinor analysis fit both the MS and ELISA data with lower SDRs than a straight-line (two-tailed t-test, p<0.0001) indicating a day/night pattern in Aβ concentrations by both methods (eTable 2).

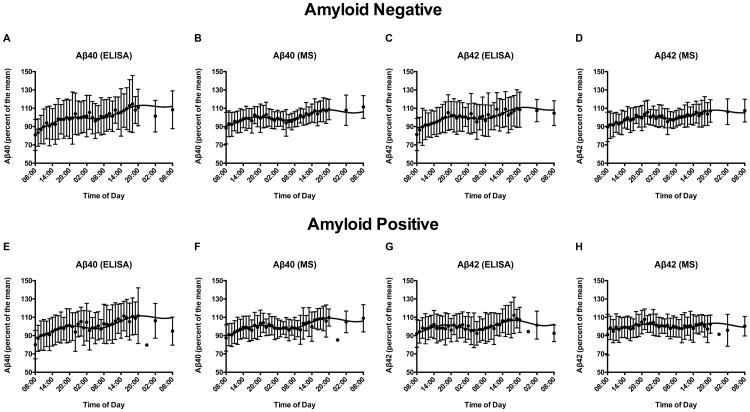

All 77 participants were separated into amyloid-negative (N=39) and amyloid-positive (N=38) groups. Aβ40 and Aβ42 percent of the mean values for both assays were averaged for each time point. The cosine wave fitted the MS group-averaged data with significantly narrower standard deviations than ELISA for both Aβ40 and Aβ42 (Figure 1A-H, all p≤0.001). We compared the individual cosinor parameters for each group. Aβ40 and Aβ42 day/night amplitude and acrophase did not differ significantly between assays in either group (all p>0.05). Aβ42 amplitude and linear rise calculated by MS was significantly decreased in amyloid-positive individuals compared to amyloid-negative (Figure 1D and 1H, p<0.002), replicating previous findings (5). However, the linear increase of Aβ40 and Aβ42 determined by the MS data was not as high compared to ELISA in both amyloid-negative and amyloid-positive groups (Figure 1A-H, p≤0.01).

Figure 1.

Cosinor analysis of percent of the mean for Aβ40 and Aβ42 measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and mass spectrometry. Group-averaged Aβ40 and Aβ42 measured in serial cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and mass spectrometry (MS) in 39 amyloid-negative (A-D) and 38 amyloid-positive (E-H) individuals over 48 hours. Concentration values were converted to percent of the mean for all participants and then averaged for each group. The cosinor fit and standard deviations are shown. MS quantitation resulted in narrower standard deviations (all p≤0.001) and therefore more precise fit to the cosine wave compared to ELISA. Amyloid-negative individuals: A. Aβ40 measured by ELISA. B. Aβ40 measured by MS. C. Aβ42 measured by ELISA. D. Aβ42 measured by MS. Amyloid-positive individuals: E. Aβ40 measured by ELISA. F. Aβ40 measured by MS. G. Aβ42 measured by ELISA. H. Aβ42 measured by MS.

Based on these findings, we conclude that MS more precisely fit the day/night oscillation of Aβ40 and Aβ42 using cosinor analysis compared to ELISA. Only Aβ concentrations measured by MS are analyzed throughout the remainder of this paper. The cosine fitted data for Aβ40 and Aβ42 measured by MS and ELISA is shown for all participants in the supplement (eFigures 1-77).

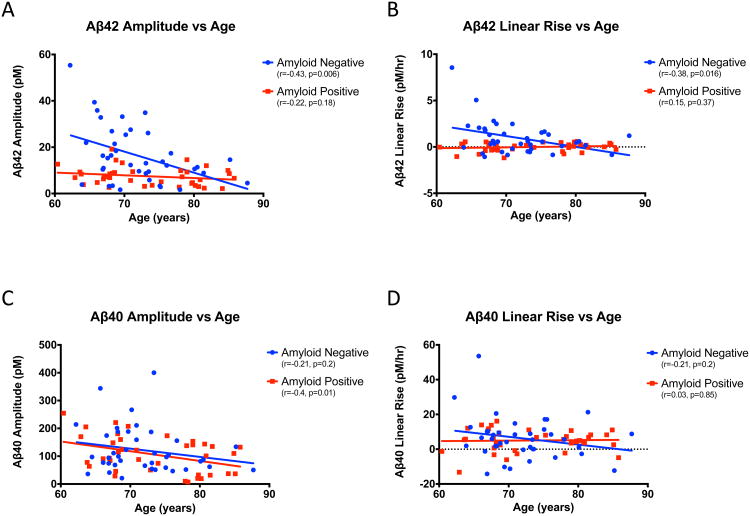

Aβ42 day/night amplitude and linear increase decline with age

Aβ40 and Aβ42 day/night amplitude and linear increase were compared to age for both amyloid-negative and amyloid-positive individuals. Aβ42 amplitude declined 0.91 pM/year in amyloid-negative subjects while Aβ42 day/night amplitudes in the amyloid-positive group did not vary significantly with age (Figure 2A). The magnitude of the Aβ42 rise with serial CSF sampling significantly declined with age in the amyloid-negative group (-0.12 pM/hour each year, Figure 2B). In contrast, there was no linear rise for Aβ42 with serial CSF sampling in amyloid-positive individuals regardless of age (0.01 pM/year, Figure 2B). After approximately 73 years old, there were no significant differences between the two amyloid groups in the average day/night amplitude or linear increase of Aβ42 (eTable 3).

Figure 2.

Relationship between Aβ amplitude and linear rise to age. A. Aβ42 amplitude (pM) vs. age (years). B. Aβ42 linear rise (pM/hr) vs. age (years). C. Aβ40 amplitude (pM) vs. age (years). D. Aβ40 linear rise (pM/hr) vs. age (years). Amyloid-negative (blue) and amyloid-positive (red) participants are shown. r- and p-values are shown. Aβ: amyloid-beta; pM: picomolar; hr: hour.

For Aβ40, both amyloid-negative and amyloid-positive groups suggested a decrease in day/night amplitude with age of 3.0-3.5 pM/year although the decline was only significant in the amyloid-positive individuals (Figure 2C). There was no age-related change in Aβ40 linear increase in either amyloid-negative or amyloid-positive participants (Figure 2D).

Relationship of amyloid burden to Aβ day/night amplitude and linear rise

Amyloid deposition decreases Aβ linear increases but has less effect on Aβ day/night amplitude (5). To assess the effect of amyloid burden, we compared the Aβ day/night amplitude and linear increase to MCBP and CSF [Aβ42]: [Aβ40] concentration ratios. Aβ42 amplitude and linear increase showed a sudden discontinuous “step-change” between amyloid-negative and amyloid-positive individuals measured by PET PIB. All amyloid-positive participants had a significant loss of amplitude variability (p=0.0003) and linear increase (p=0.02) compared to amyloid-negative individuals (eFigure 78A and 78B). Only Aβ42 amplitude was significantly correlated with MCBP (r=-0.41, p=0.006). This finding is similar to that seen with CSF [Aβ42] and MCBP in the setting of amyloid deposition (16). In contrast, Aβ40 amplitude and linear rise did not show this loss of variability with amyloid deposition (p>0.05, eFigure 78C and 78D).

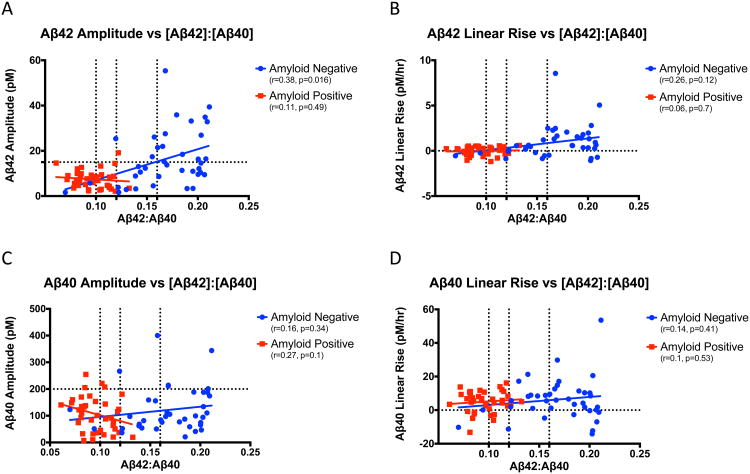

Similar relationships were observed when comparing Aβ amplitude and linear increase to [Aβ42]:[Aβ40]. For all 77 participants, Aβ42 day/night amplitude (r=-0.53, p<0.0001) and linear increase (r=-0.41, p<0.0002) correlated with [Aβ42]: [Aβ40], but Aβ40 was not (p>0.05). After separating participants into amyloid-negative and amyloid-positive groups, only Aβ42 amplitude in amyloid-negative individuals remained significant (Figure 3A). Then, we divided participants into three groups based on [Aβ42]:[Aβ40] as previously described (2): [Aβ42]:[Aβ40]<0.1, [Aβ42]:[Aβ40] 0.1-0.16, and [Aβ42]:[Aβ40]>0.16. The [Aβ42]:[Aβ40] cutoff for amyloid-positive was <0.12. When participants' [Aβ42]:[Aβ40] was 0.12-0.16, both the amplitude and linear rise of Aβ42 declined rapidly to levels similar to amyloid-positive individuals (Figure 3A and 3B). Aβ40 amplitude and linear rise do not show the same pattern (Figure 3C and 3D).

Figure 3.

Relationship between Aβ amplitude and linear rise to [Aβ42]:[Aβ40]. A. Aβ42 amplitude (pM) vs. [Aβ42]:[Aβ40] ratio. The horizontal dashed line is at 15 pM. B. Aβ42 linear rise (pM/hr) vs. [Aβ42]:[Aβ40] ratio. C. Aβ40 amplitude (pM) vs. [Aβ42]:[Aβ40] ratio. The horizontal dashed line is at 200 pM. D. Aβ40 linear rise (pM/hr) vs. [Aβ42]:[Aβ40] ratio. For all panels, the vertical dashes lines are at [Aβ42]:[Aβ40]=0.1, [Aβ42]:[Aβ40]=0.12, and [Aβ42]:[Aβ40]=0.16. Participants with the highest CSF [Aβ42]:[Aβ40] ratios (>0.16) were previously reported to have normal Aβ stable isotope labeling kinetics. Aβ SILK alterations become progressively more pronounced as the CSF [Aβ42]:[Aβ40] ratio decreases from 0.16 to 0.1 and then <0.1. For this reason, these cutoffs were used in the figures with [Aβ42]:[Aβ40] ratio. Amyloid-negative (blue) and amyloid-positive (red) participants are shown. Aβ: amyloid-beta; pM: picomolar; hr: hour.

Relationship of Aβ kinetics to Aβ day/night amplitude and linear rise

The half-life of Aβ increases by 250% between 30 to 80 years of age and the fractional turnover rate (FTR) of Aβ42 is specifically increased relative to Aβ40 in the presence of amyloid deposits, consistent with active deposition of Aβ42 relative to Aβ40 (2, 17). To assess how changes in Aβ kinetics (e.g. FTR) are associated with the day/night oscillation of Aβ, we assessed the Spearman correlations of FTR Aβ40, FTR Aβ42, FTR Aβ42/40 (elevated in amyloid-positive subjects), CSF [Aβ40], CSF [Aβ42], and Aβ production rates to Aβ40 and Aβ42 day/night amplitude and linear rise with partial correlations controlling for age and amyloid (Table 1). Complementary associations between Aβ FTRs, concentrations, production rates, and cosinor parameters are expected since the kinetic parameters are interrelated (eMethods1)(18). In this study, CSF Aβ concentration was highly correlated with the production rate but weakly with FTR (eTable 4).

Table 1. Correlations between Aβ amplitude and linear rise with age, amyloid status, and Aβ kinetics.

| Age | Amyloid | [Aβ42] | FTR Aβ42 | FTR Aβ42/40 | Aβ42 PR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aβ42 Amplitude | rs = -0.26* | rs = -0.43**** | rs = 0.53**** | rs = -0.12 | rs = -0.47**** | rs = 0.38*** |

| Control for age | rs = -0.42*** | rs = 0.515**** | rs = -0.21 | rs = -0.45**** | rs = 0.36*** | |

| Control for amyloid | rs = -0.24* | rs = 0.36*** | rs = -0.01 | rs = -0.29** | rs = 0.238* | |

| Aβ42 Linear Rise | rs = -0.11 | rs = -0.36*** | rs = 0.16 | rs = -0.18 | rs = -0.5**** | rs = -0.194 |

| Control for age | rs = -0.35** | rs = 0.15 | rs = -0.22 | rs = -0.49**** | rs = -0.21 | |

| Control for amyloid | rs = -0.07 | rs = -0.12 | rs = -0.1 | rs = -0.38*** | rs = -0.41*** | |

| Age | Amyloid | [Aβ40] | FTR Aβ40 | FTR Aβ42/40 | Aβ40 PR | |

| Aβ40 Amplitude | rs = -0.27* | rs = -0.06 | rs = 0.38*** | rs = 0.11 | rs = -0.08 | rs = 0.42*** |

| Control for age | rs = 0.04 | rs = 0.39*** | rs = -0.003 | rs = -0.03 | rs = 0.41*** | |

| Control for amyloid | rs = -0.27* | rs = 0.38*** | rs = 0.1 | rs = -0.05 | rs = 0.42*** | |

| Aβ40 Linear Rise | rs = -0.1 | rs = -0.01 | rs = -0.25* | rs = 0.28* | rs = -0.1 | rs = -0.18 |

| Control for age | rs = -0.001 | rs = -0.25* | rs = 0.26* | rs = -0.08 | rs = -0.19 | |

| Control for amyloid | rs = -0.1 | rs = -0.25* | rs = 0.28* | rs = -0.12 | rs = -0.18 |

Spearman partial correlations; Two-tailed significance

Amyloid refers to “amyloid status” as defined in the methods

FTR: Fractional Turnover Rate; PR: Production Rate; Aβ: Amyloid-β; rs=Spearman correlation

p<0.05

p≤0.01

p≤0.001

p≤0.0001

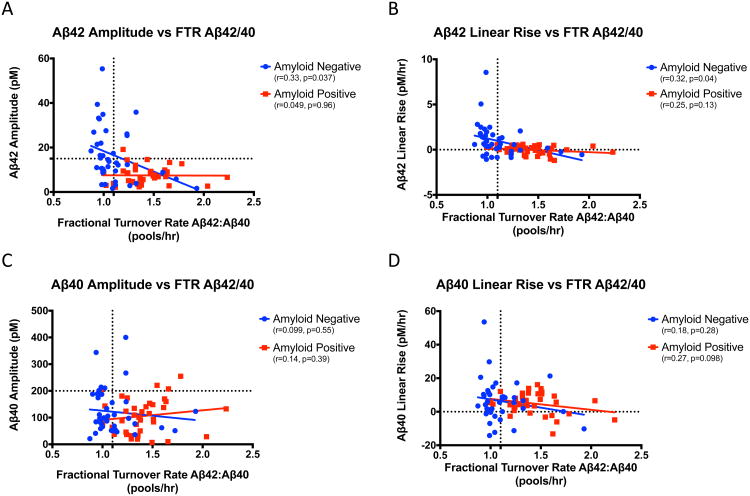

We compared CSF Aβ day/night and linear concentrations to SILK kinetic parameters of production and clearance rates, in order to determine the relationships between hypothesized mechanisms of production and clearance active during sleep and wakefulness. The FTR is the turnover rate or soluble clearance rate of Aβ. As expected, markers of amyloid deposition such as amyloid status, increased Aβ42/40 turnover rate, lower CSF [Aβ42], and increased Aβ42 production strongly correlated with low Aβ42 day/night amplitudes and linear increases regardless of age. The turnover rate of Aβ42 was not significantly associated with Aβ42 amplitude or linear rise (p>0.05). The clearance of Aβ42as measured by FTR Aβ42/40 was correlated with both Aβ42 day/night amplitude and linear rise in the amyloid-negative group, but not in the amyloid-positive group (Figure 4A and 4B). In contrast, Aβ40 day/night amplitude and linear rise were not correlated with FTR Aβ42/40 for either amyloid group (Figures 4C and 4D).

Figure 4.

Relationship between Aβ amplitude and linear rise to FTR Aβ42/40. A. Aβ42 amplitude (pM) vs. FTR Aβ42/40 ratio (pools/hr). The horizontal dashed line is at 15 pM. B. Aβ42 linear rise (pM/hr) vs. FTR Aβ42/40 ratio (pools/hr). C. Aβ40 amplitude (pM) vs. FTR Aβ42/40 (pools/hr). The horizontal dashed line is at 200 pM. D. Aβ40 linear rise (pM/hr) vs. FTR Aβ42/40 ratio (pools/hr). The vertical dashes line marks FTR Aβ42/40=1.1. Amyloid-negative (blue) and amyloid-positive (red) participants are shown. Aβ: amyloid-beta; FTR: fractional turnover rate; pM: picomolar; hr: hour.

Different relationships were found for Aβ40. Aβ40 day/night amplitude and linear increase were not changed by markers of amyloid deposition (Table 1, all p>0.05). Aβ40 amplitude was associated with age, Aβ40 production rate, and CSF [Aβ40], while Aβ40 linear rise was associated with CSF [Aβ40] and Aβ40 turnover rate. The correlations remained significant even after controlling for age and amyloid status. These findings suggest that production and clearance mechanisms affect two relatively similar peptides, Aβ42 and Aβ40, differently.

Discussion

We report the first comparison of the relationships between Aβ production and clearance rates with CSF Aβ day/night amplitude and linear increases and account for aging and amyloid deposition effects. Although longitudinal follow-up studies are needed, our results suggest that amyloid deposition leads to premature loss of Aβ42 day/night patterns associated with aging, in contrast to Aβ40 which is largely driven by production rates. These results may have implications for the design of AD prevention trials targeting Aβ production (i.e. BACE inhibitors) and using CSF Aβ as a marker of target engagement. First, these results may affect the timing of therapeutic intervention. In amyloid-negative individuals, timing of anti-amyloid intervention and age of participants may be critical factors. Adults <73 years old may benefit from anti-amyloid therapy during the day or waking hours when production and concentrations are highest. For amyloid-positive individuals, the timing of anti-amyloid therapy may be irrelevant because there are no significant time-of-day differences for Aβ are no significant most prone to aggregate into insoluble plaque. Second, sleep disturbances have been implicated in AD pathogenesis (8), potentially exacerbating amyloidosis with impaired clearance mechanisms. Improving sleep quality or treating sleep disorders to reduce Aβ production and increase clearance could decrease growth of amyloid and may prevent AD. However, this approach may not be effective in adults >73 years old or in amyloid-positive individuals of any age. Third, CSF sampling frequency and volume need to be carefully controlled in studies to avoid sampling effects that may be due to concentration gradients that give rise to linear rise, especially in those without amyloidosis.

The FTR includes a process of irreversible loss of Aβ. The strong correlations between amyloid status, FTR Aβ42/40, Aβ42 day/night amplitude and linear increase suggest that loss of Aβ42 is to amyloid plaques. The changes in Aβ42 amplitude and linear rise associated with amyloid deposition were seen at borderline [Aβ42:Aβ40] ratios between 0.12-0.16 when participants were classified as amyloid-negative. This finding complements recently published work showing that CSF Aβ42 levels are tightly correlated with cortical amyloid load and decrease markedly prior to passing the threshold for “amyloid-positive” on PET PIB (19). For Aβ40, the linear rise correlated with FTR Aβ40, but not to FTR Aβ42/40 or amyloid status. The etiology of Aβ40 loss is unclear and may be due to clearance across the blood-brain barrier, degradation, formation of higher order Aβ structures, or other causes including clearance by more frequent sampling of higher volumes of CSF. It is possible that collecting 6 ml/hour would substantially increase the clearance of Aβ species which can diffuse into the CSF and may represent the mechanism for the linear rise in Aβ seen in many CSF catheter studies.

In the last 10-15 years, multiple lumbar catheter studies have measured the effect of CSF sampling and time-of-day on CSF Aβ concentration ((5-7, 20-26), eTable 5). Several of these prior studies reported that the linear increase and day/night variability in CSF Aβ levels during serial collection depends on the sampling frequency and/or volume (7, 21, 26), possibly due to shifting CSF flow toward the lumbar space with repeated draws. However, none of these studies controlled for amyloid deposition. Our group previously reported that the amplitude of CSF Aβ oscillation decreased with age, while amyloid deposition markedly decreased linear rise (5). We have extended these findings to show that the linear rise of CSF Aβ also demonstrates an age-dependent effect and amplitude is decreased in individuals with amyloid deposition regardless of age when the draw frequency and volume is uniform. Further, these amyloid effects were observed in Aβ42 rather than Aβ40. This finding has important implications in study designs using lumbar catheters in order to control for these effects.

A major weakness of our study is the lack of sleep-wake monitoring. Decreased Aβ production from neuronal activity and increased clearance via bulk fluid flow during sleep are two mechanisms hypothesized to drive the Aβ day/night pattern. We hypothesize that both Aβ amplitude and linear increase in amyloid-negative individuals are likely dependent on the sleep-wake cycle and other factors. However, deposition into amyloid plaques acts as a “sink” and is the dominant factor affecting the Aβ42 amplitude and linear rise in amyloid-positive individuals; since Aβ42 is more likely to aggregate into insoluble plaques than Aβ40, Aβ40 amplitude and linear rise are not significantly changed. Without concurrent sleep studies, we cannot determine if variability of Aβ amplitude and linear rise in individuals less than 73 years old is affected by alterations in total sleep time or other sleep parameters.

MS is a novel assay that simultaneously measures absolute Aβ concentration and Aβ SILK. The profound age-dependent effect of amyloid on Aβ amplitude and linear rise, particularly for Aβ42, was not previously appreciated until the more precise MS method was used. We also found novel associations between Aβ concentration and production rates to Aβ amplitude and linear rise, as well as Aβ turnover and linear rise, independent of age and amyloid deposition. Further Aβ SILK studies in participants under different sleep conditions are needed to determine the sleep parameters that can manipulate Aβ production, clearance and concentrations. Understanding the factors which influence Aβ physiology throughout the sleep/wake cycle could establish potential approaches and targets for the prevention or treatment of AD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Drs. Lucey and Bateman had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Chengjie Xiong and Matt Jasielec helped with statistical analyses. Alison Goate and Carlos Cruchaga performed ApoE determination. Tammie Benzinger interpreted the PET PIB studies.

Dr. Lucey has consulted for AbbVie, Inc. and Neurim Pharmaceuticals. He owns <$5,000 of stock in Cardinal Health. Dr. Lucey receives research support from the NIH, the BrightFocus Foundation, and the McDonnell Center for Systems Neuroscience.

Dr. Mawuenyega may receive royalty income based on a patent: Methods for simultaneously measuring the in vivo metabolism of two or more isoforms of a biomolecule licensed by Washington University to C2N Diagnostics.

Dr. Patterson has provided consultations on Aβ peptide turnover kinetics for C2N Diagnostics.

Mr. Ovod may receive royalty income based on technology licensed by Washington University and tied to AGREEMENT 010395-0001.

Dr. Kasten receives a royalty from C2N for the CSF Aβ patent/protocol.

Neither Dr. Morris nor his family owns stock or has equity interest (outside of mutual funds or other externally directed accounts) in any pharmaceutical or biotechnology company. Dr. Morris has participated or is currently participating in clinical trials of antidementia drugs sponsored by the following company: A4 (The Anti-Amyloid Treatment in Asymptomatic Alzheimer's Disease) trial. Dr. Morris has served as a consultant for Lilly USA and Takeda Pharmaceuticals. He receives research support from Eli Lilly/Avid Radiopharmaceuticals and is funded by NIH grants # P50AG005681; P01AG003991; P01AG026276 and UF01AG032438.

Dr. Bateman receives research funding from the NIH, Alzheimer's Association, and an anonymous foundation. He also receives grants from the DIAN Pharma Consortium (Amgen, AstraZeneca, Biogen, Eisai, Eli Lilly and Co, FORUM, Hoffman La-Roche, Pfizer, and Sanofi) and a tau consortium (AbbVie and Biogen), has received honoraria from Roche, OECD, and Merck as a speaker, and from IMI, Sanofi, and Boehringer Ingelheim as a consultant. Dr. Bateman, Dr. Holtzman, the Chair of Neurology, and Washington University in St. Louis have equity ownership interest in C2N Diagnostics and may receive royalty income based on technology licensed by Washington University to C2N Diagnostics. In addition, Dr. Bateman and Dr. Holtzman receive income from C2N Diagnostics for serving on the Scientific Advisory Board. Washington University, with R.J.B. and D.M.H. as co-inventors, has also submitted the U.S. nonprovisional patent application “Methods for measuring the metabolism of CNS derived biomolecules in vivo,” serial #12/267,974.

This study was supported by the following: 1) NIH R01NS065667, P50AG05681, P01AG03991, UL1 RR024992, P30DK056341, P41RR000954, P41GM103422, P60DK020579, and P30 DK020579; 2) Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grants UL1 TR000448 and KL2 TR000450 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (The funding source had no role in the study design, data collection, management, analysis, interpretation of the data, or manuscript preparation); 3) the Adler Foundation (PI: RJB); 4) an anonymous foundation (PI: RJB).

Footnotes

Dr. Elbert reports no conflicts.

References

- 1.Prince M, Wimo A, Guerchet M, Ali GC, Wu YT, Prina M. World Alzheimer Report 2015: The Global Impact of Dementia: An Analysis of Prevalence, Incidence, Cost and Trends. London: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patterson BW, Elbert DL, Mawuenyega KG, Kasten T, Ovod V, Ma S, et al. Age and amyloid effects on human CNS amyloid-beta kinetics. Ann Neurol. 2015;78(3):439–53. doi: 10.1002/ana.24454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meyer-Luehmann M, Stalder M, Herzig MC, Kaeser SA, Kohler E, Pfeifer M, et al. Extracellular amyloid formation and associated pathology in neural grafts. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6(4):370–7. doi: 10.1038/nn1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang JE, Lim MM, Bateman RJ, Lee JJ, Smyth LP, Cirrito JR, et al. Amyloid-β dynamics are regulated by orexin and the sleep-wake cycle. Science. 2009;326(5955):1005–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1180962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang Y, Potter R, Sigurdson W, Santacruz A, Shih S, Ju YE, et al. Effects of age and amyloid deposition on Aβ dynamics in the human central nervous system. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(1):51–8. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roh JH, Huang Y, Bero AW, Kasten T, Stewart FR, Bateman RJ, et al. Disruption of the sleep-wake cycle and diurnal fluctuation of amyloid-β in mice with Alzheimer's disease pathology. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(150):150ra22. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lucey BP, Gonzales C, Das U, Li J, Siemers ER, Slemmon JR, et al. An integrated multi-study analysis of intra-subject variability in cerebrospinal fluid amyloid-β concentrations collected by lumbar puncture and indwelling lumbar catheter. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2015;7:53. doi: 10.1186/s13195-015-0136-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lucey BP, Bateman RJ. Amyloid-β diurnal pattern: possible role of sleep in Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35:S29–S34. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xie L, Kang H, Xu Q, Chen MJ, Liao Y, Thiyagarajan M, et al. Sleep drives metabolite clearance from the adult brain. Science. 2013;342:373–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1241224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kress BT, Iliff JJ, Xia M, Wang M, Wei HS, Zeppenfeld D, et al. Impairment of paravascular clearance pathways in the aging brain. Ann Neurol. 2014;76:845–61. doi: 10.1002/ana.24271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris JC. The clinical dementia rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–4. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berg L, Miller JP, Storandt M, Duchek J, Morris JC, Rubin EH, et al. Mild senile dementia of the Alzheimer type: 2. Longitudinal assessment. Ann Neurol. 1988;23:477–84. doi: 10.1002/ana.410230509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mintun MA, LaRossa GN, Sheline YI, Dence C, Lee S, Mach R, et al. [11C]PIB in a nondemented population: potential antecedent marker of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67:446–52. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000228230.26044.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mawuenyega KG, Kasten T, Ovod V, Lucey B, Sigurdson W, Bateman RJ. Immuno-based-LC/SRM as a Diagnostic tool for Protein Dynamics of Amyloid β Isoforms Instead of ELISA in the Clinical Laboratory. 62nd Conference on Mass Spectrometry and Allied Topics; June 15-19, 2014; Baltimore, MD. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bateman RJ, Munsell LY, Morris JC, Swarm R, Yarasheski KE, Holtzman DM. Human amyloid-β synthesis and clearance rates as measured in cerebrospinal fluid in vivo. Nat Med. 2006;12(7):856–61. doi: 10.1038/nm1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fagan AM, Mintun MA, Mach RH, Lee SY, Dence CS, Shah AR, et al. Inverse relation between in vivo amyloid imaging load and cerebrospinal fluid Amyloid-beta-42 in humans. Ann Neurol. 2006;59(3):512–9. doi: 10.1002/ana.20730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Potter R, Patterson BW, Elbert DL, Ovod V, Kasten T, Sigurdson W, et al. Increased in vivo amyloid-β 42 production, exchange, and loss in presenilin mutation carriers Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(189):189ra77. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elbert DL, Patterson BW, Bateman RJ. Analysis of a compartmental model of amyloid beta production, irreversible loss and exchange in humans. Mathematical biosciences. 2015 Mar;261:48–61. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2014.11.004. Epub 2014/12/17. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vlassenko AG, McCue L, Jasielec MS, Su Y, Gordon BA, Xiong C, et al. Imaging and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in early preclinical Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2016 doi: 10.1002/ana.24719. Epub July 11, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bateman RJ, Wen G, Morris JC, Holtzman DM. Fluctuations of CSF amyloid-β levels: implications for a diagnostic and therapeutic biomarker. Neurology. 2007;68:666–9. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000256043.50901.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li J, Llano DA, Ellis T, LeBlond D, Bhathena A, Jhee SS, et al. Effect of human cerebrospinal fluid sampling frequency on amyloid-β levels. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2012;8:295–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.05.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moghekar A, Goh J, Li M, Albert M, O'Brien RJ. Cerebrospinal fluid Aβ and tau level fluctuation in an older clinical cohort. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(2):246–50. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Slats D, Claassen JA, Spies PE, Borm G, Besse KT, Aalst Wv, et al. Hourly variability of cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in Alzheimer's disease subjects and healthy older volunteers. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33(4):831.e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dobrowolska JA, Kasten T, Huang Y, Benzinger TL, Sigurdson W, Ovod V, et al. Diurnal patterns of soluble amyloid precursor protein metabolites in the human central nervous system. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):e89998. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ooms S, Overeem S, Besse K, Rikkert MO, Verbeek M, Claassen JA. Effect of 1 night of total sleep deprivation on cerebrospinal fluid β-amyloid 42 in healthy middle-aged men: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(8):971–7. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Broeck BV, Timmers M, Ramael S, Bogert J, Shaw LM, Mercken M, et al. Impact of frequent cerebrospinal fluid sampling on Aβ levels: systematic approach to elucidate influencing factors. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2016;8(1):21. doi: 10.1186/s13195-016-0184-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.