Abstract

Facial paralysis is a rare complication of acute suppurative otitis media which requires early detection and appropriate care. We hereby report a case which we managed conservatively with good outcome. Following our experience and review of literature on the subject, antibiotic therapy and corticosteroid therapy, with or without myringotomy were found to be the first-line procedures. Surgery should be employed in case of acute or coalescent mastoiditis, suppurative complications and lack of clinical regression.

Keywords: Acute suppurative otitis media (ASOM), Corticosteroid, Lower motor neuron (LMN), Facial nerve palsy, Electro neuro myography (ENMG)

Introduction

Facial nerve palsy has become an uncommon complication of acute otitis media in the recent era, with an estimated incidence of about 0.005% [1]. It was a very common complication in the pre-antibiotic era, with an estimated incidence of around 0.5–0.7% [1]. Facial nerve paralysis secondary to ASOM is thought to be mediated by intrafallopian inflammatory edema and consequent ischemia with neuropraxia The possible factors causing the facial nerve paralysis in ASOM are likely to be alterations in the middle ear microenvironments, such as elevated pressure, osteitis, or acute inflammation, retrograde infection or due to reactivation of viruses within bony facial canal wherein facial nerve physiology may be directly affected [2]. Facial nerve palsy secondary to acute otitis media requires proper care with appropriate antibiotics, so that the requirement of any surgical intervention can be minimised.

Case Report

A 25 year old lady presented to our outpatient department with the history of right ear discharge since 2 days, watery in nature, blood tinged associated with pain in right ear and in the right half of the face aggravating on exposure to cold with no relief from oral analgesics. She also complained of drooling of saliva from right side of the mouth while drinking water and eating food, along with an asymmetry of the face and inability to close her right eye since 2 days.

On facial examination, she was found to have right sided facial palsy of lower motor neurone type, grade 2 House Brackmann scale as seen in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Patient at presentation

Local examination of the right external ear done to rule out Herpes zoster. Otoscopic examination showed congested tympanic membrane with pin hole perforation in anteroinferior quadrant with active discharge of purulent material which was blood tinged. Hearing tests revealed mild conductive hearing loss on the right ear.

Right ear swab which was taken for culture and sensitivity, revealed the growth of Staphylococcus coagulase positive organisms. Routine blood tests were performed, which showed an increase in the neutrophilic inflammatory cells and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, about 30 mm/h.

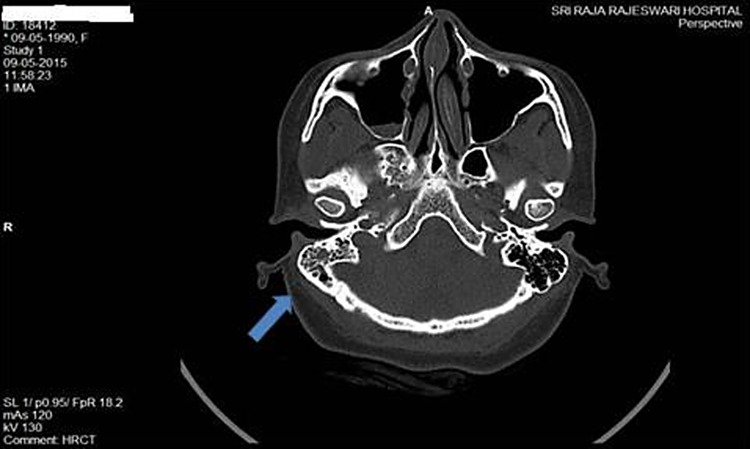

Considering the onset of facial weakness, high resolution computed tomography of temporal bone was performed with 0.7 mm cuts (Fig. 2) to detect any dehiscence in the facial canal but revealed only the soft tissue attenuation involving the right middle ear and right mastoid air cells suggestive of right otomastoiditis.

Fig. 2.

HRCT temporal bone showing acute mastoiditis

Electroneuronography was done it showed 80% degeneration.

With a suspected diagnosis of right acute suppurative otitis media with right facial nerve palsy of LMN type, patient was planned for conservative management.

Patient was treated with intravenous antibiotics (ceftazidime 1 g twice a day), intravenous corticosteroids (dexamethasone 8 mg in tapering doses) and rehabilitative measures for facial palsy in the form of eye lubricants and physiotherapy.

A gradual and significant improvement of both signs and symptoms was noted in the patient after 1 week with recovery to grade 0, as in Fig. 3, objectively confirmed by electroneuronography. Symptoms were reduced; signs of pain and discharge were decreased.

Fig. 3.

Patient post therapy

Discussion

Acute inflammation of the middle ear is one of the most common diseases seen in childhood and in early adulthood. It is usually confined within tympanic cavity and mastoid, but when the disease is severe the inflammation spreads to the structures neighbouring the middle ear cleft [1].

Fallopian canal can be involved in persistent inflammation of the middle ear, causing peripheral facial paralysis as one of the complication as was seen in our patient.

As reported by Kvestad and colleagues the rate of sequelae described in patients with peripheral facial nerve paralysis secondary to otitis media varies from 0 to 30% [7].

The possible factors causing the facial nerve paralysis in acute suppurative otitis media are likely to be alterations in the middle ear microenvironments, such as elevated pressure, osteitis, or acute inflammation, wherein facial nerve physiology may be directly affected [2].

It has also been opined that retrograde infection within facial nerve bony canal or retrograde infection within tympanic cavity can ascend via the chorda tympani nerve to facial nerve [3].

Reactivation of latent virus infection caused by middle ear suppuration has also been postulated as the cause in patients with reduced immunity [4]. Demyelination of facial nerve secondary to the presence of bacterial toxins has also been hypothesized to be a leading cause of 7th nerve paralysis in infection [5]. Rarely ASOM is known to cause acute neuritis with venous thrombosis leading to inflamatory edema of the nerve [6].

Joseph and Sperling [1], analyzed the existing theories to explain its physiopathology, and concluded that the main mechanism was a direct involvement of the nerve, being by bacterial or viral toxins [8].

However, Tschiassny’s theory described by Zinis et al. [10] explained that the infectious involvement of the facial nerve happens through the bony dehiscence and neurovascular communication between the middle ear and facial nerve [9].

Nager et al. [11] reviewing anatomical variations of the facial nerve, found 55% Fallopian canal dehiscence; this leads us to think about other physiopathological mechanisms, since peripheral paralysis as a complication of AOM is very rare [10].

Another theory suggests that the infection causes compression to the vessels that nourish the facial nerve and this could cause local ischemia and nerve infarction, and consequent paralysis.

When facial palsy appears late in the course of disease, it seems to be caused by direct extension of middle ear inflammation to the fallopian canal and poor vascular perfusion caused by inflammation [12]. During this stage it depends on silent or masked mastoiditis, a complication of acute middle ear infection which is due to inadequate antibiotic therapy [13] and aggressiveness of infectious agents.

The most common organisms recovered from cultures of patients with supparative complications of acute otitis media have been Gram positive cocci (S. Pneumonia and Staphylococcal series) [14].

Electroneuronography is also useful in patients who have poor functional outcome [16]. It has been recommended that it should be performed 3–4 days after development of complete facial nerve palsy because wallerian degeneration does not become apparent until 48–72 h after acute injury to the nerve [17]. Patients with more than 95% degeneration documented on ENog, performed no more than 14 days after appearance of the palsy, require surgical decompression of the facial nerve canal [18]. Decompression has been discouraged in the earlier phase, because of the risk of damage to the inflamed and friable nerve [4].

Electromyography is only helpful after degeneration of the nerve has occurred, since the fibrillation potentials appear 10–21 days after deterioration [3]. Electromyography at 21 days can indicate whether there is any reinnervation [18] and is thus, useful in detecting reappearance of facial nerve electrical potential.

Broad spectrum intravenous 3rd generation cephalosporins with good meningeal penetration (cefotaxime or ceftazidime 100 mg/kg per day) [15] is widely followed and hence, it was followed in our patient as well.

Conclusion

The treatment for facial nerve palsy that is secondary to acute otitis media should be treated on an emergency basis with conservative measures that includes appropriate Intravenous antibiotics and with intravenous corticosteroids for complete recovery.

Myringotomy and grommet insertion should be considered when there is a bulging tympanic membrane, collection of fluid in the middle ear or if the spontaneous perforation of the tympanic membrane does not occur.

Surgery is indicated when there is suspected silent or masked mastoiditis, a complication of acute middle ear infection which is due to inadequate antibiotic therapy and aggressiveness of infectious agents.

In our patient, the recovery was optimized due to early diagnosis, appropriate antibiotics and corticosteroids and also due to strict adherence to follow up and rehabilitation.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in this study.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participant were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient included in the study.

References

- 1.Ellefsen B, Bonding P. Facial palsy in acute otitis media. Clin Otolaryngol. 1996;21:393–395. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.1996.00810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.House JW, Brackmann DE. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1985;93:146–147. doi: 10.1177/019459988509300202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamitsuka M, Feldman K, Richardson M. Facial paralysis associated with otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1985;4:682–684. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198511000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joseph EM, Sperling NM. Facial nerve paralysis in acute otitis media: cause and management revisited. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;118:694–696. doi: 10.1177/019459989811800525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elliott CA, Zalzaal GH, Gottlieb WR. Acute otitis media and facial paralysis in children. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1996;105:58–62. doi: 10.1177/000348949610500110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobsson M, Nylen O, Tjellstrom A. Acute otitis media and facial palsy in children. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1990;79:118–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1990.tb11344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan CY, Cass SP. Management of facial nerve injury due to temporal bone trauma. Am J Otol. 1999;20:96–114. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0709(99)90018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kvestad E, Kvaerner KJ, Mair IWS. Otologic facial palsy: etiology, onset, and symptom duration. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2002;111:598–602. doi: 10.1177/000348940211100706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joseph EM, Sperling NM. Facial nerve paralysis in acute otitis media: cause and management revisited. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;118:694–696. doi: 10.1177/019459989811800525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nager GT, Proctor B. Anatomic variations and anomalies involving the facial canal. Otolaryngol Clin N Am. 1991;24:531–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zinis LOR, Gamba P, Balzanelli C. Acute otitis media and facial nerve paralysis in adults. Otol Neurotol. 2003;24:113–117. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200301000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukuda T, Sugie H, Masataka I, Kikawada T. Bilateral facial palsy caused by bilateral masked mastoiditis. Pediatr Neurol. 1998;18:351–353. doi: 10.1016/S0887-8994(97)00197-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tovi F, Leibermann A. Silent mastoiditis and bilateral simultaneous facial palsy. Int J Pediatric Otorhinolaryngol. 1983;5:303–307. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5876(83)80043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zapalac JS, Billings KR, Schwade ND, Roland PS. Suppurative complications of acute otitis media in the era of antibiotic resistance. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:660–663. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.6.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spratley J, Silveria H, Alvarez I, Pais-Clemente M. Acute mastoiditis in children: review of the current status. Int J Pediatric Otorhinolaryngol. 2000;56:33–40. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5876(00)00406-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qiu WW, Yin SS, Stucker FJ, Hoasjoe DK. Neurophysiological evaluation of acute facial paralysis in children. Int J Pediatric Otorhinolaryngol. 1997;39:223–236. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5876(97)01498-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knox GW. Treatment controversies in Bell’s palsy. Arch Otilaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124:821–823. doi: 10.1001/archotol.124.7.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan CY, Cass SP. Management of facial nerve injury due to temporal bone trauma. Am J Otol. 1999;20:96–114. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0709(99)90018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]