Abstract

Nanoparticle-mediated photothermal therapy for treatment of different types of tumors has attracted tremendous attention in recent years. One major factor that drives this therapy is the ability to carefully control and prevent inadvertent damage to local tissues, while focusing therapeutic heating to specific regions of the tumor tissues. To this end, it is critical to generate efficient heating in the targeted tumors while monitoring the extent and distribution of heating. In our study, we demonstrated the photothermal heating properties of our synthesized branched Au nanoparticles (b-AuNPs) using non-invasive MR thermometry (MRT) techniques to assess its effects both in vitro and in vivo. 75 nm b-AuNPs were synthesized; these b-AuNPs demonstrated strong near infrared (NIR) absorption and high heat transducing efficiency. Proton resonance frequency MRT approaches for monitoring b-AuNPs mediated heating were validated using in vitro agar phantoms and further evaluated during in vivo animal model tumor ablation studies. In vitro phantom studies demonstrated a strong linear correlation between MRT and reference-standard thermocouple measurements of b-AuNPs-mediated heating upon NIR laser irradiation; temperatures increased with both an increase in laser power and increased exposure duration. Localized photothermal heating in regions containing the b-AuNPs was confirmed through MRT generated temperature maps acquired serially at increasing depths during both phantom and in vivo studies. Our results suggested that b-AuNPs exposed to NIR radiation produced highly efficient localized heating that can be accurately monitored dynamically using non-invasive MRT measurements.

Keywords: MRI, Photothermal, cancer therapy, Au nanoparticles, image guided therapy

INTRODUCTION

Tumors can be thermally ablated by the local application of heat, which induces irreversible cell injury and results in tumor apoptosis and coagulative necrosis. The most common techniques for therapeutic heat delivery are radiofrequency,1–3 microwave, 4,5 laser,6–8 and high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU).9–11 These thermal ablation therapies have several potential advantages over surgical resection, such as lower morbidity, increased preservation of surrounding tissues, reduced cost, and shorter duration of hospitalization.12 However, disadvantages include incomplete ablation resulting in recurrence of disease.13,14 If the delivery of heat is not carefully controlled, excessive damage to surrounding normal tissues may occur.

Lasers, delivering electromagnetic radiation, can permit efficient local ablation of tumor tissues. However, because light is easily scattered, this modality has limited tissue penetration (~1–2 cm) and generally ablates tissue non-specifically.2,14 The application of photothermal sensitizers, which can increase the heat generated by incident laser light, may overcome this limitation by focusing the ablation to specific regions (i.e., tumor) thus increasing the local effects of the incident radiation and reducing unwanted ablation of surrounding healthy tissues. Photothermal transducing nanoparticles are mostly designed to have their absorption band at the near infrared (NIR) range, where radiant energy exhibits excellent penetration through water and biological tissues allowing for efficient delivery of energy to the sites of targeted tumor tissues. In particular, gold nanostructures exhibit high heat transduction efficiency due to surface plasmon resonance (SPR), a phenomenon in which the conductive free electrons resonate in response to incoming electromagnetic radiation and dissipate heat.15,16 Gold nanostructures of various geometries have been suggested as photothermal sensitizers, including nanorods,15,17 nanoshells,18,19 nanocages,20–23 and nanostars.24,25 Despite their advantageous optical properties, conventional gold nanostructures have been limited for practical utilization, because their fabrication is both time consuming and difficult, requiring multiple procedures: preparation and dissolution of template materials, 19,23 primary seed preparation for anisotropic crystal growth,26,27 and rigorous washing steps to remove cytotoxic surfactants.28–30

Branched-gold nanoparticles (b-AuNPs), among the various types of Au nanostructures, are powerful candidates for clinical ablation therapy, because they can be easily prepared with a nontoxic surfactant and high-yield, and b-AuNP can have excellent photothermal transduction efficiency in the NIR region.31 However, to ensure the safety and efficacy of b-AuNPs mediated NIR photothermal ablation (PTA) procedures, it will be necessary to monitor the propagation of heat throughout the target volume. Confirmation that cytotoxic temperatures are obtained at the intended ablation zone is crucial to ensure complete tumor treatment and prevent inadvertent damage to local adjacent tissues. Conventionally, multiple thermocouples or IR thermometers have been used to measure the heat distribution of tumors, but it is challenging to obtain accurate intra-tumoral temperature profiles using these techniques. Internal temperature monitoring of tumors as well as tumor surface measurements during PTA is critically needed. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a widely used noninvasive modality diagnostic imaging and for guidance interventional procedures. Several MR parameters can be measured non-invasively for assessment of temperature: proton density, spin-lattice relaxation time (T1), spin-spin relaxation time (T2), relaxation times of water protons, diffusion coefficient, magnetization transfer, and the proton resonance frequency (PRF) of water molecules.32–35 Of the various parameters, the PRF is preferred basis for temperature measurements, due to good temperature sensitivity, near-independence with respect to tissue type, and linear relationship between PRF and temperature change within the range typically encountered during thermal ablation procedures (−15 to 100°C).36 PRF based magnetic resonance thermometry (MRT) for monitoring of thermal ablation has been intensely studied.37–40 However, few papers41,42 reported possible MRT temperature monitoring of AuNPs-mediated NIR photothermal heating.

Herein, we report MRT–monitoring of b-AuNPs mediated NIR photothermal heating within in vitro phantoms and an in vivo human xenograft prostate cancer mouse model. Successful implementation of MRT guided thermal therapy should allow clinicians to accurately visualize target tumors and monitor temperature changes in real-time during b-AuNPs mediated photothermal heating for precise, targeted ablation of tumor tissues.

EXPERIMENTAL

Chemicals

Hydrochloroauric acid (HAuCl4·3H2O), silver nitrate (AgNO3), and L-ascorbic acid were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, USA). Sodium cholate bile acid was purchased from Pierce (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, USA). All the chemicals were analytical grade reagents and used without further purification. Milli-Q water was used during the study.

Synthesis of branched Au Nanoparticles (b-AuNPs)

b-AuNPs were synthesized by Au nanocrystal growth in a solution of HAuCl4·3H2O, L-ascorbic acid, AgNO3, and sodium cholate molecules, as modification of the previously reported.31 To synthesize b-AuNPs, a milliliter of 10 mM HAuCl4·3H2O was added to 10 mL of 0.24 mM sodium cholate acid. After the resulting solution had been thoroughly mixed, 150 μL of 10 mM AgNO3 was added and mixed for 1 min. Next, 150 μL of 100 mM L-ascorbic acid was added and shaken for 1 min. Within a few seconds after the addition of L-ascorbic acid, the color of the mixture changed from yellow to blue, then to dark blue, indicating that the b-AuNPs were generated. The resulting b-AuNP solution was maintained at room temperature for 3 h, then washed and redispersed in Milli-Q water. The synthesized b-AuNPs were modified with thiol-poly(ethylene glycol)-carboxymethyl (SH-PEG-CM, MW 3400. Da) (Laysan Bio Inc, Alabama, USA).

Sample characterization

The crystal structure, morphology and size of the synthesized b-AuNPs were characterized using an X-ray diffractometer (XRD; Scintag XDS-2000), transmission electronic microscope (TEM; FEI Tecnai Spirit G2) operating at 120 kV. The absorption spectra of the samples were recorded on a Lambda 1050 spectrophotometer (Perkin-Elmer, USA). The hydrodynamic size, size-distribution and zetapotential of the samples were investigated with dynamic light scattering (DLS) using a Zetasizer Nano-S (Malvern, Germany) equipped with a 4 mW HeNe laser.

In vitro cytotoxicity evaluation of b-AuNPs

A human prostate cancer cell line (PC-3, Manassas, VA) was cultured and suspended within RPMI media. 100 μL of PC-3 cells at a concentration of 4×104/mL were plated into each well of a 96 well-plate and incubated for 12 h. 20 μL of b-AuNPs were added at concentrations from 0 to 3600 μg/mL and incubated for 4 h. Cell culture media was replaced with fresh media to remove free b-AuNPs. Then, 10 μL of CCK-8 solution was added to each well to evaluate cell viability and incubated with cells for 2 h before measuring absorption at 450 nm with a plate reader (Molecular Devices, USA).

Determination of Photothermal Transduction Efficiency of b-AuNPs

Solutions of 1% agarose with b-AuNPs were prepared at concentrations of 80, 90, and 100 μg/mL, along with a control of 0 μg/mL. Samples of each concentration were pipetted into a 96-well plate (BD Falcon, Franklin Lakes, NJ). The optical density of each sample was determined with a Lambda 1050 spectrophotometer (Perkin-Elmer, USA) using an irradiation wavelength of 808 nm. Lasing and subsequent heating of each sample was performed with an 808 nm laser (B&W Tek Inc., Newark, DE) set to powers ranging from 150 to 500 mW/cm2 with the optical fiber tip placed 1 cm above the center of each sample’s surface. Lasing was performed for 15 minutes, achieving a steady maximum temperature. Heating was quantitatively evaluated with an infrared thermal camera (Infrared Cameras Inc, Beaumont, TX). The power value of laser was measured using an optical power meter (ADC Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Calculation of the photothermal transduction efficiency was performed in a similar manner as previously established in literature.43,44 The total energy balance can be described as:

| (1) |

where m and Cp are the mass and specific heat, respectively, of the solvent (1% agarose). T represents the temperature of the sample. Ein is the energy input based on the heat dissipated by the nanoparticles and the solvent and can be represented as:

| (2) |

where I represents the lasing power, OD is the sample’s optical density at 808 nm, and η is the photothermal transduction efficiency. Eext is the external energy flux between the sample and its surrounding environment, and can be represented as:

| (3) |

where h represents the heat transfer coefficient, A is the sample’s surface area, T(t) is the temperature at time t, and Ta is the ambient temperature. The quantity, hA can be determined by measuring the sample’s cooling once the laser is turned off, Equation 1 then becomes:

| (4) |

where ΔT =T(t)–Ta. Solving for T(t) using T(0)=Tmax, the steady state maximum temperature at which the laser is turned off:

| (5) |

Taking the natural logarithm and rearranging Eq. (5) results in:

| (6) |

the quantity hA can be estimated by determining the slope of the linear relationship depicted in Eq. (6). At the maximum steady state temperature at which the laser is turned off, the rate of heating is equal to the rate of heat flux out of the sample, which can be described as:

| (7) |

As such, the photothermal transduction efficiency can then be directly determined:

| (8) |

MRI temperature measurements in b-AuNPs embedded phantoms upon NIR laser irradiation

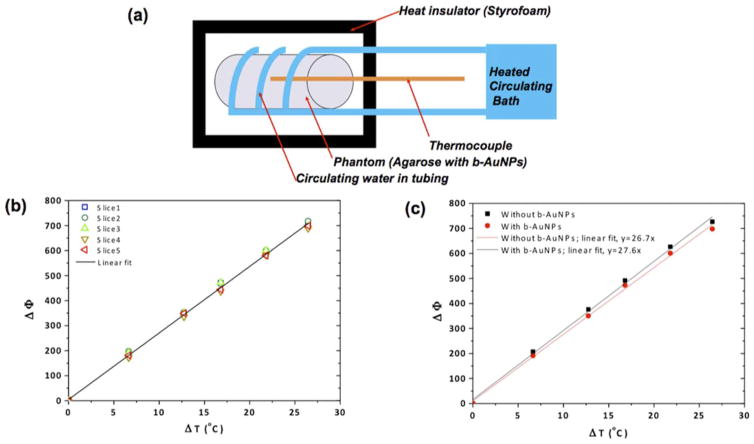

Phantoms were made by filling cylindrical vials and petri dishes with solutions of b-AuNPs (50 μg/mL) in 1% agarose to calibrate temperature versus MR signal phase measurements [Figure 3(a)]. Another cylindrical vial phantom containing one layer of 1% agarose with (25 μg/mL) b-AuNPs and another equally sized layer of 1% agarose without AuNPs was produced to determine if the addition of b-AuNPs affected MR signal phase measurements [Figure 3(c)]. The petri-dish phantoms were used for MR determination of temperature changes during laser irradiation. Once the agarose solution within the petri-dish had cooled and gelled, the phantom was sectioned in half and a thermocouple was inserted for comparative measurements. The optical fiber tip from an 808 nm laser was placed 1 cm from the edge of the hemi-section, and lasing was performed for 5 minutes at 187.6 mW/cm2, 293.6 mW/cm2, 361.2 mW/cm2, and 463.7 mW/cm2. Phase images were obtained during lasing and converted to temperature maps using the initially obtained calibration curve. A 7 Tesla MRI scanner (Clinscan, Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) and a gradient-recalled echo sequence (TE=1.22 ms, TR=80.00 ms, flip angle=40 degrees) were used.

FIGURE 3.

(a) Schematic of experimental setup used to compare MR signal phase changes and thermocouple measured temperature changes. (b) MR signal phase change measurements (ΔΦ) plotted against thermocouple temperature measurements (ΔT) performed at multiple positions (adjacent imaging slices) within laser irradiated region containing of b- AuNPs. (c) MR signal phase change measurements (ΔΦ) compared to thermocouple temperature measurements (ΔT) performed after laser irradiation of phantoms with and without b-AuNPs.

MRI Temperature Measurements and b-AuNPs mediated PTA in PC-3 Xenografts

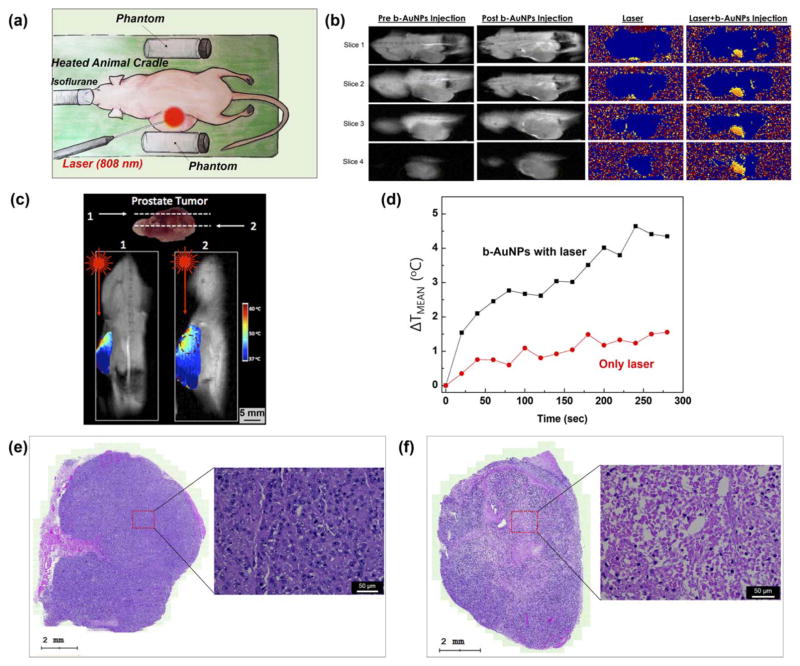

All animal studies were performed in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Northwestern University. PC-3 cells were cultured and suspended within RPMI media and subcutaneously inoculated (0.1 mL; 2 × 105 cells) onto the backs of 2–3 weeks old immune compromised CB17-Prkd c SCID/J mice (n=3). 4 weeks were allowed for tumor growth (< 1 cm diameter). 0.1 mL of b-AuNPs in saline at a concentration of (0.6 mg/mL) was inoculated into the tumor via several small injections of varying locations and depths. Experimental lasing and heating of the tumor was performed using an 808 nm laser with the optical fiber tip directed toward the tumor and placed 1 cm away from the tumor’s surface. The lasing outputs were set to 293.6 mW/cm2 and 361.2 mW/cm2, with continuous lasing for 5 minutes during each trial. MRI phase images were obtained during the lasing. For non-invasive MRT within the mice, we implemented MRI temperature measurements based on the PRF using a 7 Tesla MRI scanner and a gradient-recalled echo sequence (TE=1.22 ms, TR=80.00 ms, flip angle=40 degrees). Images from four coronal slices, each 2 mm apart, were obtained. The mice were sedated with isoflurane and secured upon a heated animal cradle within the MRI scanner bore, maintaining a physiologic temperature of 37°C. Two acrylic vials filled with 1% agarose were also secured upon the heated animal cradle, one directly adjacent to the heating element, and one a small distance away. The mice were promptly euthanized following the experiment, and the tumor tissues were harvested and stained with H&E to assess for evidence of NIR photothermal damages.

Data Analysis

All image processing, including conversion from phase images to temperature maps and calculation of average ROI values were performed in MATLAB (Mathworks Inc, Natick, MA). Plotting of quantitative data and linear regressions were performed in Origin (OriginLab Corp, Northampton, MA).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

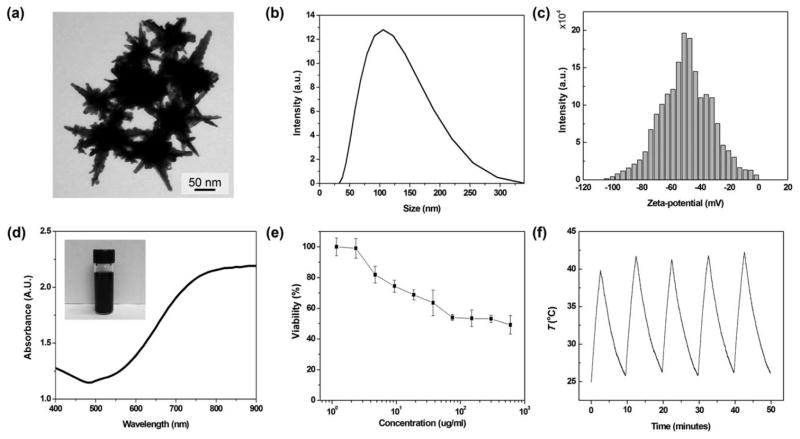

To synthesize b-AuNPs, an aqueous solution of sodium cholate guided the formation of branched gold nanostructures after addition of reducing agent, l-ascorbic acid, in the presence of gold ions.31 The synthesized b-AuNPs that we used for the PTA had a mean size of 78 nm and sharp-tipped branches 21–53 nm in length [Figure 1(a)]. The hydrodynamic size of the PEGylated b-AuNPs in aqueous solution (Milli-Q water) was 113 nm, as shown in Figure 1b. In addition, PEGylated b-AuNPs are physiologically stable with high zeta-potential, −50.4 mV in PBS (pH 7.2) [Figure 1(c)]. Elongation of the Au branches of these AuNPs is associated with a red-shift in the longitudinal plasmon peak. 21–53 nm b-AuNPs showed a significant NIR absorption band at 840 nm [Figure 1(d)]. The extended sharp ends of the b-AuNPs induced a SPR peak at 840 nm with large local electric field.45–47 These NIR absorbing b-AuNPs should be applicable as photothermal transducers for targeted tumor ablation. The NIR region is called the “tissue therapeutic window” because of the relatively low optical attenuation from water and blood within this spectral range (650–900 nm).48 Cytotoxicity studies demonstrated that PC-3 cell viability was>50% upon to PEG coated b-AuNP exposures of up to 700 μg/mL, suggesting suitability for in vivo applications [Figure 1(e)]. Furthermore, thermal stability of b-AuNPs was confirmed by monitoring temperature profile of the solution during five cycles of lasing and cooling. The maximum temperatures in every cycles were stably maintained during 5 cycles [Figure 1(f)].

FIGURE 1.

(a) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image of the synthesized b-AuNPs. Scale bar is 50 nm. (b) Hydrodynamic size of b-AuNPs, measured with DLS. (c) Zeta-potential of b- AuNPs, dispersed in phosphate buffered-saline (PBS). (d) Absorbance spectrum of b-AuNPs in aqueous solution, exhibiting strong absorption of light within the NIR range. The inset digital camera image shows an aqueous suspension of b-AuNPs. (e) Cytotoxicity of b-AuNPs during PC-3 cell exposure studies (no laser irradiation). (f) Temperature profile of b-AuNPs with repetitive cycles of the lasing and cooling (one cycle for 10 minutes). A b-AuNPs solution (0.5 mg/mL) was irradiated with laser density of 293.6 mW/cm2 for 3 minutes.

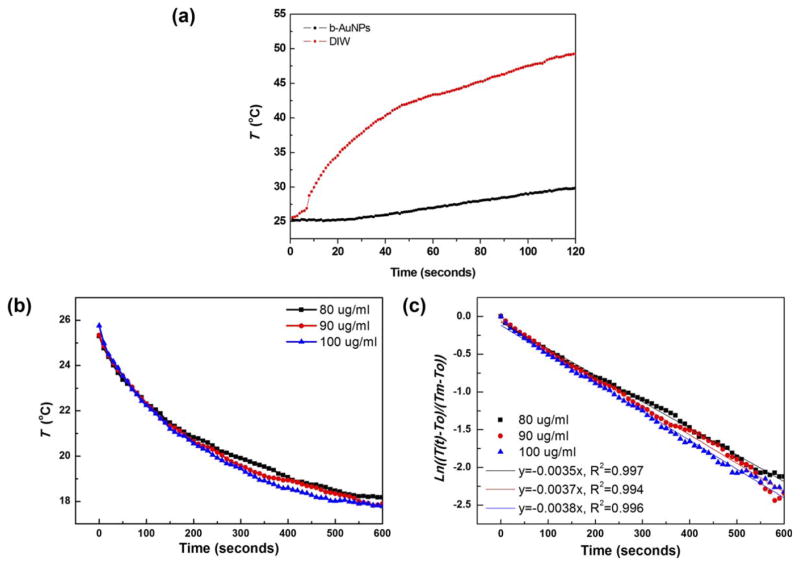

NIR electromagnetic waves (laser) are coupled with electrons upon b-AuNPs and trigger SPR resulting in heat-transduction. 15,49 In our study, laser irradiation of a solution containing 1 mg/mL b-AuNPs laser (power: 293.6 mW/cm2, wavelength 808 nm) achieved temperature increases of up to 50°C (sufficient for irreversible damage to malignant cells12) while a control group (distilled water without b-AuNPs) showed only ~3°C temperature increase [Figure 2(a)]. Next, we evaluated the heating transduction efficiency. The heat transduction efficiency of our b-AuNPs was obtained with the energy balance equation and time–dependent cooling curves in Figure 2b. Firstly, hA (where h is the heat transfer coefficient and A is the surface area of b-AuNPs) was obtained by linearizing the cooling curve with the natural logarithm [Figure 2(c)]. Theoretically and based on the equations we used, the efficiency should not be affected by the concentration of b-AuNPs in solution. This is assuming that the concentration is low enough such that the specific heat of the solution remains that of water. We used three different concentrations to confirm and to have multiple measurements, obtaining transduction efficiencies of 58%, 52%, and 57% for b-AuNPs at a concentration of 100, 90, and 80 μg/mL, respectively. Overall, b-AuNPs transduction efficiency of ~56%, greater than other gold nanostructures such as gold nanoshells and nanorods, with reported efficiencies of 25% and 50%, respectively.43

FIGURE 2.

(a) Time dependent heating curve for b-AuNPs in aqueous solution and distilled water without b-AuNPs during laser irradiation (power: 293.6 mW/cm2, wavelength 808 nm). (b) Cooling curve of b-AuNP suspensions at three different concentrations after irradiation with 808 nm laser for 15 minutes. (c) Linearized cooling curve of b-AuNP suspensions after applying the natural logarithm. From the slope, the quantity hA was calculated with Eq. (6).

MR temperature mapping during laser irradiation was conducted within a petri-dish hemisection phantom, containing b-AuNPs of 50 μg/mL in 1% of agarose gel. Dynamic acquisition of MR images (both magnitude and phase) was performed both before and during exposure to NIR laser (808 nm) which induced heating of the phantom. Temperature changes were monitored with a thermocouple. The setup for this experiment is illustrated in Figure 3a. MR signal phase and reference thermocouple measurements were performed at 5 different positions within the cylindrical phantoms [Figure 3(a)]; a strong linear correlation was observed between temperature changes (ΔT) and MR signal phase change (ΔΦ) at each position (R2 values>0.99), as shown in Figure 3b. PRF–based temperature mapping relies on the principle that temperature changes lead to linearly proportional PRF shifts resulting in phase changes (ΔΦ) in the recorded MR signal. The linear relationship between ΔT and ΔΦ is described as shown below. Temperature change, ΔT can be estimated according to MRI measurements of ΔΦ:

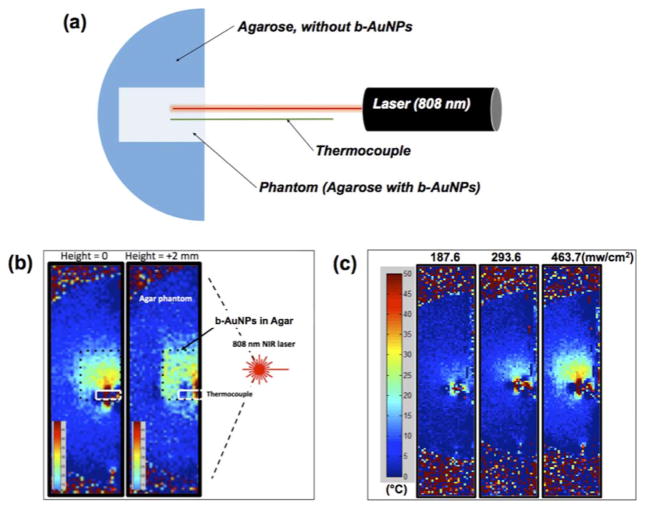

with known parameters of α chemical shift, γ gyromagnetic ratio, β static magnetic field, and TE echo time, respectively. However, it was also critical to evaluate the presence of our b-AuNP alone (independent of laser induced photothermal heating), would impact the accuracy of the MRT measurement. Thus, we compared thermocouple ΔT and MR signal ΔΦ measurements in agarose phantoms with and without b-AuNP [Figure 3(c)]. The addition of b-AuNPs did not significantly impact phase measurements during MRT studies [Figure 3(c)] (strong linear correlation demonstrated between ΔT and ΔΦ independent of b-AuNP, R2 values>0.99 and slopes were differed<0.5%). Phase change images were converted into temperature maps with a baseline calibration according to the thermocouple measurements. Next, in vitro MRT was performed in agarose phantoms that included region containing the b-AuNPs [Figure 4(a)]. Spatial temperature mapping visualized the inner heating distribution in the agarose phantoms. The two temperature maps displayed depict the heat distributions at the center and at a slice positioned 2 mm vertically below [Figure 4(b)]. Well-localized heating in the regions containing the b-AuNPs (enclosed within dashed-box overlays, Figure 4b) was readily observed upon irradiation with the externally positioned laser (808 nm). Finally, laser power dependent heating was also confirmed with MRT. As expected, higher irradiation powers resulted in enlarged regions of temperature change within the b-AuNP containing phantom; as laser power was increased from 187.6 to 463.7 mW/cm2, the heated region was markedly enlarged [Figure 4(c)]. The highest temperature detected was roughly 50°C upon exposure to a 463.7 mW/cm2 laser power for 5 min.

FIGURE 4.

(a) Schematic illustration of experimental set-up for magnetic resonance thermometry (MRT) during irradiation of with NIR laser (λem: 808 nm); temperature of agarose phantom with 50 μg/mL of b-AuNPs, embedded in hemi-sectioned agarose gel is detected with a thermocouple. (b) Temperature maps from inside of agarose phantom [at center (height=0) and 2 mm above the center of phantom (height=2 mm)]. (Irradiation with laser density of 463.7 mW/cm2 for 5 minutes, (c) Measured MRT temperature maps of center slices (height=0) in agarose phantoms at exposed to three different laser densities: 187.6 mW/cm2, 293.6 mW/cm2, and 463.7 mW/cm2 for 5 mins, respectively.

The feasibility of using these methods for in vivo MRT monitoring during b-AuNPs mediated NIR PTA was demonstrated in xenograft PC3 mouse model. A custom-made cradle was used for in vivo temperature mapping in mice during MRT [Figure 5(a)]. The cradle was kept at physiologic temperature, 37°C, and included two agarose phantoms for temperature monitoring and calibration [Figure 5(a)]. One phantom was adjacent to the tumor and the cradle’s heating element, while the other was placed at a distance away from the heating element as a control. A mouse with human PC-3 prostate xenograft tumor was placed on the cradle for PTA therapy. MRI phase images were obtained during laser irradiation of the tumor, both before and after intratumoral injection with b-AuNPs [Figure 5(a)]. During irradiation with NIR laser, both coronal MR magnitude images and phase images at 4 slice positions within the tumor were obtained and converted into temperature maps [Figure 5(b)]. The injected AuNPs did not affect the MR signal and the heat distribution in a tumor was effectively detected with the MRT measurements [Figure 5(b)]. Each coronal slice obtained during irradiation allowed in vivo visualization of the intra-tumoral temperature distributions [Figure 5(b)]. These MRT temperature map measurements demonstrated that b-AuNPs mediated photothermal approaches were able to achieve temperature increases of up to 60°C, more than sufficient to achieve irreversible cytotoxic damage and subsequent cell death [Figure 5(b)]. Furthermore, quantitative analysis of the extent of intratumoral heating was performed by first isolating the portion of the temperature map corresponding to the tumor. A 3 mm diameter ROI was centered over an intratumoral point of maximal heating, and the temperature data within the ROI averaged. Temperature maps with a lower bound of 43°C, the ablation threshold, were generated to visualize of the distribution of heating considered adequate for ablation [Figure 5(c)]. These MRT measurements permitted calculation of the volumetric size of the region that achieved therapeutic ablation temperatures>43°C (51.64% relative to overall tumor volume for example in Figure 5c suggesting complete tumor ablation would require adjustment to laser probe position). To confirm selective b-AuNPs mediated photothermal heating, MRT measurements in b-AuNPs treated animals were compared to MRT measurements in tumor exposed to laser irradiation alone. After 5 minutes of NIR laser irradiation at 293.6 mW/cm2, the laser-only treated tumor reached a ΔTmean of 1.5°C (mean ΔT within 3 mm ROI at tumor position of maximal heating), whereas both of the b-AuNPs and laser treated tumor achieved a ΔTmean of 4.8°C [Figure 5(d)]. Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) stained tumor slices from non-treated control showed negligible damage with healthy extracellular matrix [Figure 5(e)]. However, a tumor treated with b-AuNPs and NIR laser irradiation demonstrated significant damage with shrinkage of cells and eruption of extracellular matrix [Figure 5(f)] consistent anticipated histopathologic signatures of successful PTA in a treated region, as demonstrated in previous PTA results of b-AuNPs.31 This validated b-AuNPs mediated photothermal heating and temperature monitoring by MRT should allow image guiding AuNPs mediated photothermal therapy for precise ablation of tumor tissues minimizing normal tissues damages.

FIGURE 5.

(a) Schematic illustration of mouse cradle for photothermal tumor ablation while imaging with MRT. A mouse with PC-3 prostate xenograft is settled between two phantoms: one is adjacent to tumor and the other is at a distance for calibration purposes. (b) Magnitude MRI images pre (leftmost) and post (second) b-AuNPs injection, and MR temperature map images during laser irradiation pre (third) and post (rightmost) inoculation with b-AuNPs. (c) Temperature maps, obtained after tumor irradiation with lasing density of 361.2 mW/cm2 for 5 minutes (images at two different depths, demonstrating spatial distribution of heating in a tumor). (d) Time dependent mean temperature change measurements (ΔTmean) within tumor ROIs during irradiation with lasing density of 293.6 mW/cm2 (both for b-AuNP treated tumor and tumor exposed only to laser irradiation). (e) Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining histology depicting untreated control tumor and (f) b-AuNPs injected tumor after NIR irradiation (lasing density of 293.6 mW/cm2 for 5 minutes). Scale bar is 50 μm.

CONCLUSION

We developed an approach for dynamic MRT–monitoring of b-AuNPs mediated PTA of solid tumors. The synthesized b-AuNPs had relatively long branched shapes, thereby strong SPR absorbance at NIR wavelengths with heat transduction efficiency of ~56% upon exposure to an 808 nm NIR laser. Our in vitro MRT studies in b-AuNPs embedded agarose phantoms demonstrated that MR phase images collected during irradiation with a NIR laser can be directly converted into temperature maps for non-invasive temperature monitoring. Phase differences at each time lapse were proportional to the temperature dependent PRF changes, enabling the calculation of photothermal heating mediated by the presence of our b-AuNPs. We validated the accuracy of these MRT methods and applied these during initial in vivo feasibility studies to demonstrate the potential to non-invasively monitor photothermal heating in tumor tissues during b-AuNPs mediated PTA. The demonstrated b-AuNPs mediated photothermal local heating and MRT visualization are expected to permit precise and targeted ablation of tumor tissues by clinicians.

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsor: National Cancer Institute and National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering; contract grant numbers: R01CA141047, R21CA173491, R21EB017986, R21CA185274

Contract grant sponsor: Center for Translational Imaging at Northwestern University

References

- 1.Curley SA, Izzo F, Delrio P, Ellis LM, Granchi J, Vallone P, Fiore F, Pignata S, Daniele B, Cremona F. Ann Surg. 1999;230:1–8. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199907000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dupuy DE, Goldberg SN. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12:1135–1148. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61670-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chu KF, Dupuy DE. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:199–208. doi: 10.1038/nrc3672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shibata T, Iimuro Y, Yamamoto Y, Maetani Y, Itoh K, Konishi K. Radiology. 2002;223:331–337. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2232010775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simon CJ, Dupuy DE, Mayo-Smith WW. Radiographics. 2005;25:S69–S84. doi: 10.1148/rg.25si055501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.LeVeen RF. Semin Interv Radiol. 1997;14:313–324. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pacella CM, Bizzarri G, Magnolfi F, Cecconi P, Caspani B, Anelli V, Bianchini A, Valle D, Pacella S, Manenti G, Rossi Z. Radiology. 2001;221:712–720. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2213001501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stern JM, Stanfield J, Kabbani W, Hsieh JT, Cadeddu JRA. J Urol. 2008;179:748–753. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill CR, terHaar GR. Br J Radiol. 1995;68:1296–1303. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-68-816-1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kennedy JE, ter Haar GR, Cranston D. Br J Radiol. 2003;76:590–599. doi: 10.1259/bjr/17150274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kennedy JE. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:321–327. doi: 10.1038/nrc1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chu KF, Dupuy DE. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:199–208. doi: 10.1038/nrc3672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brace C. Ieee Pulse. 2011;2:28–38. doi: 10.1109/MPUL.2011.942603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmed M, Brace CL, Lee FT, Goldberg SN. Radiology. 2011;258:351–369. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10081634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang XH, El-Sayed IH, Qian W, El-Sayed MA. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2115–2120. doi: 10.1021/ja057254a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Link S, El-Sayed MA. Int Rev Phys Chem. 2000;19:409–453. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jana NR, Gearheart L, Murphy CJ. Adv Mater. 2001;13:1389–1393. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gobin AM, Lee MH, Halas NJ, James WD, Drezek RA, West JL. Nano Lett. 2007;7:1929–1934. doi: 10.1021/nl070610y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lal S, Clare SE, Halas NJ. Account Chem Res. 2008;41:1842–1851. doi: 10.1021/ar800150g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen J, Saeki F, Wiley BJ, Cang H, Cobb MJ, Li ZY, Au L, Zhang H, Kimmey MB, Li XD, Xia YN. Nano Lett. 2005;5:473–477. doi: 10.1021/nl047950t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen JY, Wang DL, Xi JF, Au L, Siekkinen A, Warsen A, Li ZY, Zhang H, Xia YN, Li XD. Nano Lett. 2007;7:1318–1322. doi: 10.1021/nl070345g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen JY, Wiley B, Li ZY, Campbell D, Saeki F, Cang H, Au L, Lee J, Li XD, Xia YN. Adv Mater. 2005;17:2255–2261. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skrabalak SE, Chen JY, Sun YG, Lu XM, Au L, Cobley CM, Xia YN. Account Chem Res. 2008;41:1587–1595. doi: 10.1021/ar800018v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang SJ, Huang P, Nie LM, Xing RJ, Liu DB, Wang Z, Lin J, Chen SH, Niu G, Lu GM, Chen XY. Adv Mater. 2013;25:3055–3061. doi: 10.1002/adma.201204623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yuan H, Fales AM, Vo-Dinh T. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:11358–11361. doi: 10.1021/ja304180y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jana NR, Gearheart L, Murphy CJ. J Phys Chem B. 2001;105:4065–4067. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nikoobakht B, El-Sayed MA. Chem Mater. 2003;15:1957–1962. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi BS, Iqbal M, Lee T, Kim YH, Tae G. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2008;8:4670–4674. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2008.ic18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boca SC, Astilean S. Nanotechnology. 2010;21 doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/21/23/235601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leonov AP, Zheng J, Clogston JD, Stern ST, Patri AK, Wei A. Acs Nano. 2008;2:2481–2488. doi: 10.1021/nn800466c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim DH, Larson AC. Biomaterials. 2015;56:154–164. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.03.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen J, Daniel BL, Pauly KB. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;23:430–434. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee JS, Parasoglou P, Xia D, Jerschow A, Regatte RR. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1707. doi: 10.1038/srep01707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McDannold N. Int J Hyperthermia. 2005;21:533–546. doi: 10.1080/02656730500096073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vesanen PT, Zevenhoven KC, Nieminen JO, Dabek J, Parkkonen LT, Ilmoniemi RJ. J Magn Reson. 2013;235:50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quesson B, de Zwart JA, Moonen CT. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2000;12:525–533. doi: 10.1002/1522-2586(200010)12:4<525::aid-jmri3>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ellis DS, Manny TB, Jr, Rewcastle JC. Urology. 2007;70:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lambert EH, Bolte K, Masson P, Katz AE. Urology. 2007;69:1117–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muto S, Yoshii T, Saito K, Kamiyama Y, Ide H, Horie S. Japan J Clin Oncol. 2008;38:192–199. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hym173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Da Rosa MR, Trachtenberg J, Chopra R, Haider MA. Cancer Imaging. 2011;11(Spec No A):S3–8. doi: 10.1102/1470-7330.2011.9003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Melancon MP, Elliott A, Ji X, Shetty A, Yang Z, Tian M, Taylor B, Stafford RJ, Li C. Invest Radiol. 2011;46:132–140. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181f8e7d8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hirsch LR, Stafford RJ, Bankson JA, Sershen SR, Rivera B, Price RE, Hazle JD, Halas NJ, West JL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13549–13554. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2232479100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pattani VP, Tunnell JW. Laser Surg Med. 2012;44:675–684. doi: 10.1002/lsm.22072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang K, Smith DA, Pinchuk A. J Phys Chem C. 2013;117:27073–27080. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao WB, Park J, Caminade AM, Jeong SJ, Jang YH, Kim SO, Majoral JP, Cho J, Kim DH. J Mater Chem. 2009;19:2006–2012. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chithrani BD, Ghazani AA, Chan WCW. Nano Lett. 2006;6:662–668. doi: 10.1021/nl052396o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jain PK, Lee KS, El-Sayed IH, El-Sayed MA. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:7238–7248. doi: 10.1021/jp057170o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weissleder R. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:316–317. doi: 10.1038/86684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kennedy LC, Bickford LR, Lewinski NA, Coughlin AJ, Hu Y, Day ES, West JL, Drezek RA. Small. 2011;7:169–183. doi: 10.1002/smll.201000134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]