Abstract

The storage of potato tuber (Solanum tuberosum L.) at low temperatures minimizes sprouting and disease but can cause cold-induced sweetening (CIS), which leads to the production of the cancerogenic substance acrylamide during the frying processing. The aim of this research was to investigate the effects of UV-C treatment on CIS in cold stored potato tuber. ‘Atlantic’ potatoes were treated with UV-C for an hour and then stored at 4 °C up to 28 days. The UV-C treatment significantly prevented the increase of malondialdehyde content (an indicator of the prevention of oxidative injury) in potato cells during storage. The accumulation of reducing sugars, particularly fructose and glucose, was significantly reduced by UV-C treatment possibly due to the regulation of the gene cascade, sucrose phosphate synthase, invertase inhibitor 1/3, and invertase 1 in potato tuber, which were observed to be differently expressed between treated and untreated potatoes during low temperature storage. In summary, UV-C treatment prevented the existence of oxidative injury in potato cells, thus, lowered the amount of reducing sugar accumulation during low temperature storage of potato tubers.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13197-016-2433-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: UV-C, Cold-induced sweetening, Potato tuber, Storage, Gene expression

Introduction

Low temperature storage is an effective and convenient way to prolong the processing period of potato tubers, by inhibiting sprouting and decay. However, low temperature storage has been shown to accelerate the cold-induced sweetening (CIS) of potato during storage, an important element determining the frying quality of potato tubers (Dale and Bradshaw 2003; Vijay et al. 2016). This is mainly because of the occurrence of Maillard reaction, which generates dark colored products as well as the probable carcinogen- acrylamide during frying processing, is increased in susceptible potatoes (Mottram et al. 2002; Shallenberger et al. 2002). To alleviate the problem, research has been focused on decreasing the content of total reducing sugars in potato tubers as the most effective method to decrease acrylamide content in fried potatoes (Muttucumaru et al. 2008).

CIS has been widely studied in potato tubers (Foukaraki et al. 2016; Mehdi et al. 2013; Wiberley-Bradford et al. 2016), and it has been reported that CIS occurs due to an imbalance between the metabolism of starch and sugar (Ezekiel et al. 2010). The degradation pathway from starch to hexoses is complex, and several enzymes are involved in this progress, including sucrose synthase (SuSy), sucrose phosphate synthase (SPS), ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase small subunit (AGPase), granule-bound starch synthase (GBSS) (Wiberley-Bradford et al. 2014). Researchers proposed that the sucrose enters into the vacuole, where it can be cleaved to glucose and fructose, which was catalyzed by acid invertase (INV) (Sowokinos 2001). However, the activity of INV, which can be reversely regulated by invertase inhibitor (INH), has been reported to be the most important factor in regulating the contents of reducing sugars (Mckenzie et al. 2005, 2013). The regulation of sugar metabolism was clearly understood in potato tubers, but how this process was regulated under different stress conditions or treatments remains poorly studied.

UV-C treatment is a cheap, safe and convenient technique for postharvest storage, which has been widely used in controlling microorganism in many fresh products during storage (Allende and Artes 2003). UV-C is also an effective measure to maintain the quality of fresh fruit and vegetables, such as strawberry (Xie et al. 2015). Researches have reported that UV-C treatment may increase the contents of nutritional metabolites in fresh fruits and vegetables (Cisneros-Zevallos 2003). However, a previous report indicated that the content of vitamin C was decreased by UV-C treatment in fresh-cut fruits (Alothman et al. 2009). Several researches have been conducted on potato tubers, for example, UV-C reduced sprout growth in potato with no deleterious effects on tuber quality (Cools et al. 2014). Little research has been conducted on the effect of UV-C treatment on CIS of potato tuber.

In the present study, ‘Atlantic’ potatoes were treated with UV-C for an hour on each side, and then stored at 4 °C for up to 28 days. The variation of weight loss, respiration intensity, sugars and expressions of starch-sugar metabolism related genes were analyzed. The objective is to investigate the effects of UV-C treatment on physiological response of potato during low temperature storage.

Materials and methods

Plant material and treatments

Tubers of ‘Atlantic’ potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) with uniform size were harvested from orchards in Zhangjiakou, Beijing. After curing for seven days under room temperature, potatoes were placed at 20 cm below UV-C lamps, with 254 nm UV photons, and irradiated for 1 h on each side. After irradiation, both the treated and untreated potatoes were stored at 4 °C with 85–95% relative humidity (RH) and sampled at 0, 3, 7, 14 and 28 days after treatment. Each sample consisted of twelve potatoes, which were divided into three replicates. The peeled flesh of potatoes at each sampling point was stored at −80 °C.

Weight loss analysis

The weight for each potato was recorded at each sampling point. The weight loss rate was calculated according to the following algorithm: Weight loss (%) = (m0 − m)/m0 × 100%, where ‘m0’ represents the potato weight at the first day, ‘m’ represents weight of potato at each sampling point of both control and treatments.

CO2 production analysis

Three potatoes were sealed in one bottle. The gas constituents of each treatment were analyzed by gas analyzer (checkmate 3, PBI-DanSenser, Denmark) after an incubation of 2 h at 4 °C on each sampling day. The respiration rate was calculated based on the gas constituent variation. Four replicates were used in this analysis.

Sugar content analysis

A total of 0.2 g (dry weight) sample powder was homogenized with 4 mL of 80% ethanol. The mixture was extracted with ultrasonic for 30 min at room temperature, and centrifuged at 10,000×g for 15 min. Aliquots of 1 mL of the upper phase were dried under pure nitrogen. The residue was dissolved in 1 mL ddH2O and filtered through a membrane with 0.22 μm pore size.

A volume of 10 μL for each sample was injected into the ion chromatograph (ICS-3000, Dionex, USA) fitted with Carbo PacTMPA20 column (3 mm × 150 mm). The column temperature was 35 °C, and the flow rate was 0.5 mL min−1. The gradient elution buffer was used as follows: A, ddH2O; B, 250 mmol L−1 NaOH; Equal gradient of 92.5% A and 7.5% B were used for elution. A pulsed amperometric detector with gold electrode was used. Identification of the substances was according to the retention time (RT) of standard compounds. The contents of glucose, fructose, sucrose and galactose were calculated by comparison with standard curves. Total reducing sugar was calculated as total amount of glucose, fructose and galactose.

MDA content analysis

Malondialdehyde (MDA) content was determined based on the method described by Heath and Packer 1968 with modifications. One gram (dry weight) of each sample was homogenized in 10 mL 10% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid, and then centrifuged at 10,000×g for 10 min. Thiobarbituric acid (3 mL 0.67%) were added into 3 mL of supernatant. The mixture was incubated in a boiling water bath for 15 min, and then centrifuged. The MDA content was calculated based on the absorbencies at 450, 532 and 600 nm, according to the following formula: MDA (mol L−1) = [6.45 × (A532 − A600) − 0.56 × A450] × 10−6. The MDA contents in the samples were calculated and used for analysis.

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA of the potato tuber was extracted using RNA prep Pure Plant Kit (Tiangen, China). First strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg RNA, after digestion of genomic DNA, using iScriptTM cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad). Three biological replicates were included in this analysis.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Primers used in the research were included in supplementary Table 1. The β-tubulin2 gene was included as an internal control, and was shown to be stable in the conditions used (data not shown). The SuSy, SPS, AGPase, GBSS, INV and INH gene expression studies were conducted on Power SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix kit (Applied Biosystems) and ABI 7500 instrument (Applied Biosystems).

Data analysis

The figures were drawn using Origin 8.6 software (Microcal Software Inc., Northampton, MA, USA). Least significant difference (LSD) at the 0.05 level was calculated by SPSS Statistics 22 Software.

Results

Physiological response of potato under UV-C treatment

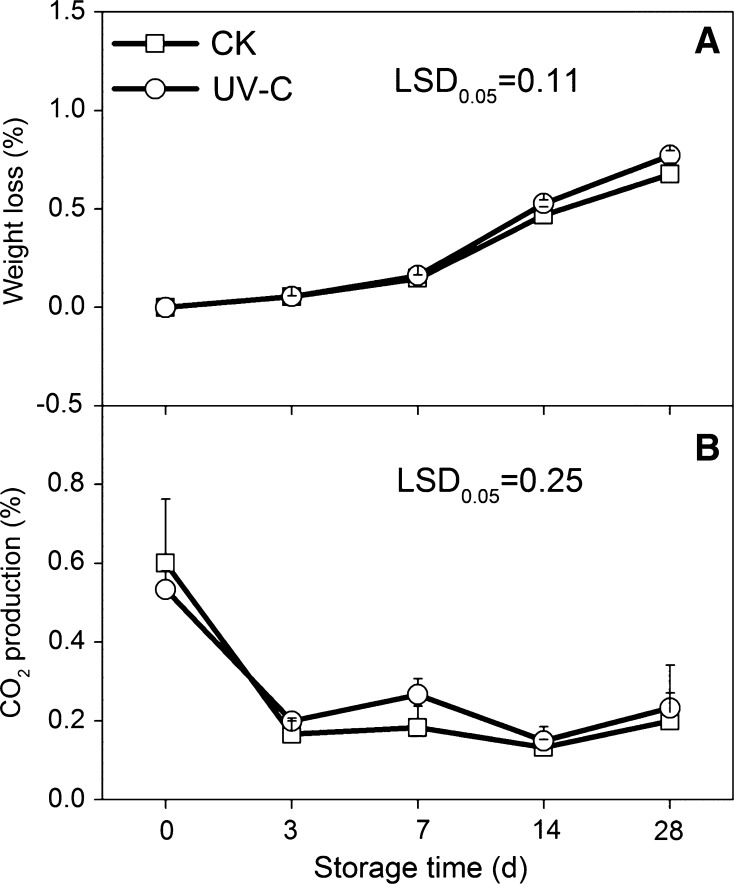

Weight loss rate was observed to increase continuously in both the control and the UV-C treated potatoes during the whole storage period, with 0.67 and 0.77% weight loss on 28 days storage in control (CK) and UV-C treated potatoes, respectively. No significant difference was observed between the control and the UV-C treated potatoes during storage (Fig. 1a). A rapid drop of CO2 production (3.6- and 2.6-fold in CK and UV-C treated potatoes, respectively) occurred on 3 days storage and was relatively remained stable during the subsequent low temperature storage. No significant difference was observed between the control and UV-C treated potatoes (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Effects of UV-C treatment on weight loss (a) and CO2 production (b) in potato tubers during low temperature storage. The error bars represent the standard errors. LSDs represent least significant differences at the 0.05 level

Resistance response of potato under UV-C treatment

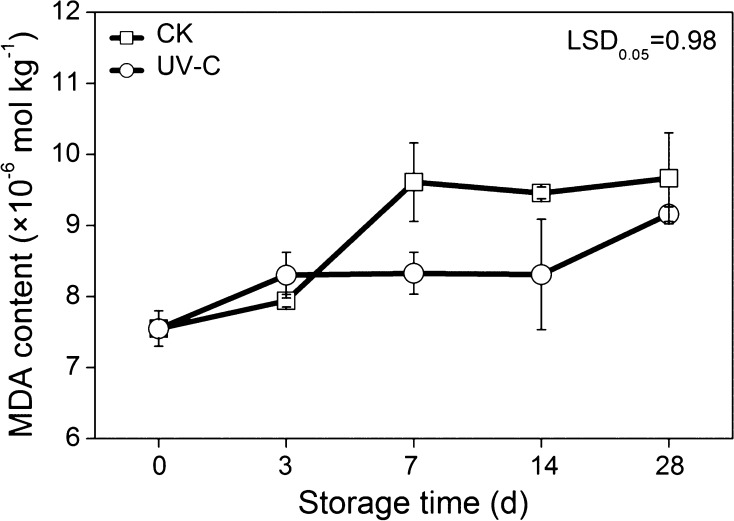

Malondialdehyde is the main product of cell membrane lipid peroxidation. Throughout the storage period, MDA content increased in both the control and the treated samples. Compared with the UV-C treated potatoes, the MDA content in the CK samples increased more rapidly. Significant differences were observed between the treatments at 7 and 14 days storage, with 1.28 × 10−6 and 1.48 × 10−6 mol kg−1 higher MDA content than control, respectively (Fig. 2). These results indicated that UV-C treatment could prevent the existence of the potato oxidative injury during storage.

Fig. 2.

Effects of UV-C treatment on MDA content in potato tubers during low temperature storage. The error bars represent the standard errors. LSDs represent least significant differences at the 0.05 level

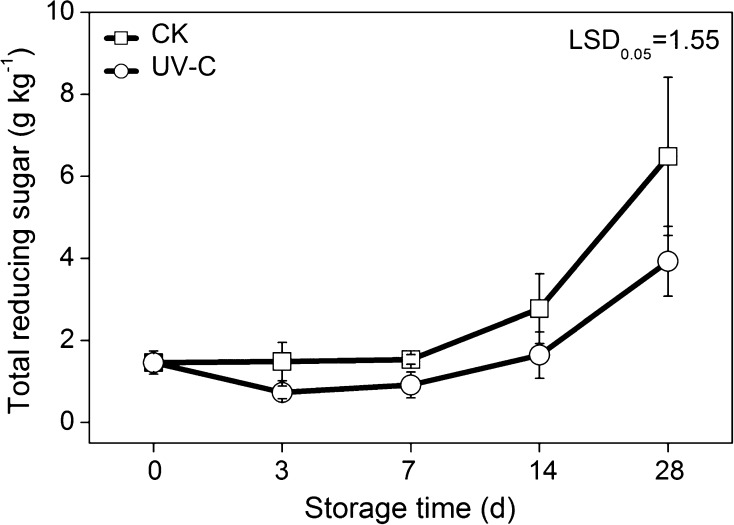

Total reducing sugar levels increased in the potato tubers of both the control and the UV-C treatment during storage. Compared with UV-C treated potatoes, total reducing sugar in control potatoes increased more rapidly, reaching a content of 6.48 g kg−1 on 28 days storage, which was 1.65 times higher than that in UV-C treated potatoes at the same stage. Total reducing sugar in control samples was constantly higher than that of the UV-C treated samples, by 1.65–2.02-fold, during the whole storage period. Thus, UV-C treatment was observed to be effective in alleviating the reducing sugar accumulation in potato tubers during low temperature storage (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Effects of UV-C treatment on total reducing sugar content in potato tubers during low temperature storage. The error bars represent the standard errors. LSDs represent least significant differences at the 0.05 level

Individual sugar contents variation

Four soluble sugar compounds were measured in present research, including fructose, glucose, sucrose and galactose, with sucrose being considered as the predominant soluble sugar in the mature potato tuber. Fructose and glucose contents during postharvest storage of potato increased continuously in both CK and UV-C treated samples. The fructose and glucose contents in the CK samples increased more rapidly than UV-C treated samples, and significant differences were observed between the CK and the UV-C treated potatoes. After 28 days storage, fructose and glucose in CK potatoes were 0.92 and 1.62 g kg−1 higher than that in UV-C treated potatoes, respectively (Fig. 4a, b). Sucrose content increased continuously during the whole storage period in both samples, while galactose decreased slightly and then increased during the later storage stages. No significant difference was observed in sucrose and galactose contents between CK and UV-C treated potatoes (Fig. 4c, d).

Fig. 4.

Effects of UV-C treatment on fructose (a), glucose (b), sucrose (c) and galactose (d) contents variation in potato tubers during low temperature storage. The error bars represent the standard errors. LSDs represent least significant differences at the 0.05 level

Expressions of sugar metabolism related genes

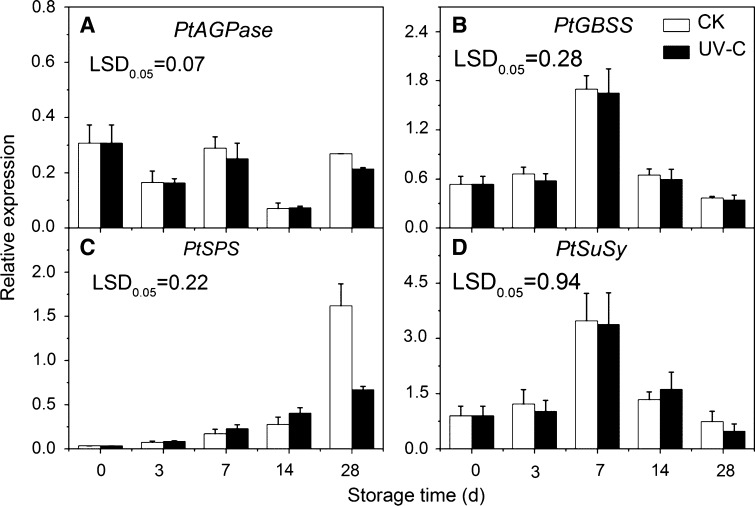

Expression of PtAGPase was irregular in both control and UV-C treated potatoes during storage, no significant difference was observed between two treatments (Fig. 5a). PtGBSS expression increased rapidly during the early storage stage and dropped rapidly during the later stage, no significant difference was investigated between CK and UV-C treated samples (Fig. 5b). The expression of PtSPS increased continuously during the whole storage period in both control and treatment. Significant differences between CK and UV-C treated samples were observed on 28 days storage, where expression of PtSPS in the CK was 2.41 times higher than that in the UV-C treated samples (Fig. 5c). The expression of PtSuSy was similar with PtGBSS (Fig. 5d).

Fig. 5.

Expressions of PtAGPase (a), PtGBSS (b), PtSPS (c) and PtSuSy (d) in control and UV-C treated potato tubers during low temperature storage. The error bars represent the standard errors. LSDs represent least significant differences at the 0.05 level

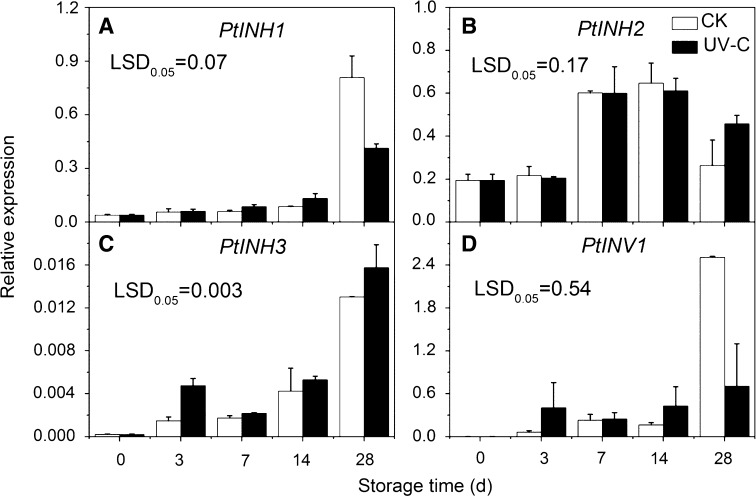

PtINH1 increased continuously during the postharvest storage in both potato samples, significant differences in PtINH1 expression were observed at 28 days storage, where PtINH1 expression in the CK was 1.95 times higher than that in UV-C treated potatoes (Fig. 6a). PtINH2 expression increased during the later storage, but no significant difference was observed between samples (Fig. 6b). Significant differences in PtINH3 expression were observed on 3 and 28 days storage, which showed 68 and 20% higher expressions in UV-C treated potatoes than control samples 3 and 28 days storage, respectively (Fig. 6c). The expression of PtINV1 was induced, by 6.3-fold, by UV-C treatment at 3 days storage, but showed a relatively constant trend during later storage period in the UV-C treatment. Significant difference was observed between samples at 28 days storage (Fig. 6d).

Fig. 6.

Expressions of PtINH1 (a), PtINH2 (b), PtINH3 (c) and PtINV1 (d) in control and UV-C treated potato tubers during low temperature storage. The error bars represent the standard errors. LSDs represent least significant differences at the 0.05 level

Discussion

UV-C significantly decreased the MDA content in potato tubers during cold storage. Such a response could indicate a reduction in membrane injury by UV-C pretreatment. Previously it has been reported that UV-C could increase the ability of stress resistance in various products. For example, UV-C treatment has been shown to modify the cell structure in tomato fruit surface and thereby could play an important role in the resistance of infection (Charles et al. 2008). UV-C has also been shown to increase the levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in both eukaryotic and prokaryotic organisms (Salma et al. 2016), change the membrane fatty acid composition of cells (Ghorbal et al. 2013), and enhance the antioxidant activity of products (Wu et al. 2016). Thus, it can be concluded that UV-C pretreatment promotes the ability of stress resistance in potato tuber during cold storage.

Sugar accumulation is a response phenomenon under different stresses, such as cold stress (Malone et al. 2006), osmotic and salinity stress (Watanabe et al. 2012), and water stress (Kameli and Lösel 1996). This may related to the fact that the sugars are effective in the regulation of osmotic pressure in plant cells. Researchers have also shown that over-expression of vacuole sugar transporter AtSWEET16 may modify the process of stress tolerance in Arabidopsis (Klemens et al. 2013). Sugar-induced tolerance to the herbicide atrazine in Arabidopsis seedlings has also been shown to be related to the oxidative and xenobiotic stress responses (Sulmon et al. 2006). Our results suggested that the reducing sugars, particular glucose and fructose, were significantly decreased under UV-C pretreatment. There is a possibility that the UV-C treatment promotes the ability of stress resistance in potato tuber, thus, leading to alleviated reducing sugar accumulation during cold storage.

CIS is a consequence of an imbalance between metabolism of starch and sugars, and may be closely regulated by gene expression. The results of this paper illustrate a trend for the increased expression of PtSPS in control potatoes, which was significantly induced in UV-C treatment potatoes at 28 days storage. Previously it has been reported that transcriptional activation occurred after three weeks of cold storage in potato plants (Reimholz et al. 2008). From our results, PtINH3 and PtINV1 were induced immediately after the UV-C treatment, while PtINH1 was differently expressed during late storage period. Researchers have also shown a close correlation among INH, INV and reducing sugars. For instance, it has been reported that the vacuolar invertase gene was strongly induced by low temperature storage in potato tuber (Liu et al. 2011); the suppression of invertase activity by silencing INV1 caused a significant reduction of sugar accumulation in cold-stored potato tubers (Bhaskar et al. 2010); overexpression of INH in transgenic potato tubers significantly reduced INV activity and the accumulation of reducing sugars (Greiner et al. 1999). Thus, our results suggested PtINH1/3 and PtINV1 could be important regulators in determining the extent of CIS during storage of potato tubers under UV-C pretreatment.

In summary, UV-C treatment significantly alleviated the membrane injury and promoted the ability of stress resistance in potato tuber during cold storage, which led to decreased accumulation of reducing sugars, particularly fructose and glucose, and was probably through the regulation of the gene cascade, PtSPS-PtINH1/3-PtINV1, during cold storage of potato tubers.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Young Scientist’s Fund of National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (No. 31601527) and the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program (ASTIP) from the Chinese Central Government.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

Q.L., Z.W. and W.G. conceived and designed the experiments; Q.L. and Y.X. performed the experiments; Q.L., Y.X. and S.C. analyzed the data; W.L., J.Z. and X.X. contributed materials and analysis tools; Q.L. wrote the paper.

Footnotes

Qiong Lin and Yajing Xie contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Qiong Lin, Email: linqiong@caas.cn.

Yajing Xie, Email: xieyajing@caas.cn.

Wei Liu, Email: liuwei@caas.cn.

Jie Zhang, Email: zhangjie@caas.cn.

Shuzhen Cheng, Email: chengshuzhen@caas.cn.

Xinfang Xie, Email: xiexinfang@caas.cn.

Wenqiang Guan, Email: gwq18@163.com.

Zhidong Wang, Phone: +86-10-62815877, Email: wangzhidong@caas.cn.

References

- Allende A, Artes F. UV-C radiation as a novel technique for keeping quality of fresh processed ‘Lollo Rosso’ lettuce. Food Res Int. 2003;36:739–746. doi: 10.1016/S0963-9969(03)00054-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alothman M, Kaur B, Fazilah A, Bhat R, Karim AA. Ozone-induced changes of antioxidant capacity of fresh-cut tropical fruits. Innov Food Sci Emerg. 2009;10:512–516. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2009.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskar PB, et al. Suppression of the vacuolar invertase gene prevents cold-induced sweetening in potato. Plant Physiol. 2010;154:939–948. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.162545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles MT, Makhlouf J, Arul J. Physiological basis of UV-C induced resistance to Botrytis cinerea in tomato fruit: II. Modification of fruit surface and changes in fungal colonization. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2008;47:27–40. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2007.05.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cisneros-Zevallos L. The use of controlled postharvest abiotic stresses as a tool for enhancing the nutraceutical content and adding-value of fresh fruits and vegetables. J Food Sci. 2003;68:1560–1565. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2003.tb12291.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cools K, Alamar MDC, Terry LA. Controlling sprouting in potato tubers using ultraviolet-C irradiance. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2014;98:106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2014.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dale MFB, Bradshaw JE. Progress in improving processing attributes in potato. Trends Plant Sci. 2003;8:310–312. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(03)00130-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezekiel R, Rana G, Singh N, Singh S. Physico-chemical and pasting properties of starch from stored potato tubers. J Food Sci Technol. 2010;47:195–201. doi: 10.1007/s13197-010-0025-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foukaraki SG, Cools K, Chope GA, Terry LA. Impact of ethylene and 1-MCP on sprouting and sugar accumulation in stored potatoes. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2016;114:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2015.11.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbal SKB, et al. Changes in membrane fatty acid composition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in response to UV-C radiations. Curr Microbiol. 2013;67:112–117. doi: 10.1007/s00284-013-0342-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greiner S, Rausch T, Sonnewald U, Herbers K. Ectopic expression of a tobacco invertase inhibitor homolog prevents cold-induced sweetening of potato tubers. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:708–711. doi: 10.1038/10924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath RL, Packer L. Photoperoxidation in isolated chloroplasts: I. Kinetics and stoichiometry of fatty acid peroxidation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1968;125:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(68)90654-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kameli AK, Lösel DM. Growth and sugar accumulation in durum wheat plants under water stress. New Phytol. 1996;132:57–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1996.tb04508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemens PAW, et al. Overexpression of the vacuolar sugar carrier AtSWEET16 modifies germination, growth, and stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2013;163:1338–1352. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.224972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, et al. Systematic analysis of potato acid invertase genes reveals that a cold-responsive member, StvacINV1, regulates cold-induced sweetening of tubers. Mol Genet Genomics. 2011;286:109–118. doi: 10.1007/s00438-011-0632-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone JG, Mittova V, Ratcliffe RG, Kruger NJ. The response of carbohydrate metabolism in potato tubers to low temperature. Plant Cell Physiol. 2006;47:1309–1322. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcj101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mckenzie MJ, Sowokinos JR, Shea IM, Gupta SK, Lindlauf RR, Anderson JAD. Investigations on the role of acid invertase and UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase in potato clones with varying resistance to cold-induced sweetening. Am J Potato Res. 2005;82:231–239. doi: 10.1007/BF02853589. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mckenzie MJ, Chen RKY, Harris JC, Ashworth MJ, Brummell DA. Post-translational regulation of acid invertase activity by vacuolar invertase inhibitor affects resistance to cold-induced sweetening of potato tubers. Plant Cell Environ. 2013;36:176–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehdi R, Morteza A, Saeed M, Farzad P. Impact of post-harvest radiation treatment timing on shelf life and quality characteristics of potatoes. J Food Sci Technol. 2013;50:339–345. doi: 10.1007/s13197-011-0337-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mottram DS, Wedzicha BL, Dodson AT. Acrylamide is formed in the maillard reaction. Nature. 2002;419:448–449. doi: 10.1038/419448a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muttucumaru N, Elmore JS, Curtis T, Mottram DS, Parry MA, Halford NG. Reducing acrylamide precursors in raw materials derived from wheat and potato. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:6167–6172. doi: 10.1021/jf800279d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimholz R, Geiger M, Haake V, Deiting U, Krause KP, Sonnewald U, Stitt M. Potato plants contain multiple forms of sucrose phosphate synthase, which differ in their tissue distributions, their levels during development, and their responses to low temperature. Plant Cell Environ. 2008;20:291–305. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.1997.d01-83.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salma KBG, Lobna M, Sana K, Kalthoum C, Imene O, Abdelwaheb C. Antioxidant enzymes expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa exposed to UV-C radiation. J Basic Microb. 2016;56:736–740. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201500753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shallenberger RS, Smith O, Treadway RH. Food color changes, role of the sugars in the browning reaction in potato chips. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;7:274–277. doi: 10.1021/jf60098a010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sowokinos JR. Biochemical and molecular control of cold-induced sweetening in potatoes. Am J Potato Res. 2001;78:221–236. doi: 10.1007/BF02883548. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sulmon C, Gouesbet G, Amrani AE, Couée I. Sugar-induced tolerance to the herbicide atrazine in Arabidopsis seedlings involves activation of oxidative and xenobiotic stress responses. Plant Cell Rep. 2006;25:489–498. doi: 10.1007/s00299-005-0062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijay P, Ezekiel R, Rakesh P. Sprout suppression on potato: need to look beyond CIPC for more effective and safer alternatives. J Food Sci Technol. 2016;53:1–18. doi: 10.1007/s13197-015-1980-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe S, Kojima K, Ide Y, Sasaki S. Effects of saline and osmotic stress on proline and sugar accumulation in Populus euphratica in vitro. Plant Cell Tissue Organ. 2012;63:199–206. doi: 10.1023/A:1010619503680. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiberley-Bradford AE, Busse JS, Jiang J, Bethke PC. Sugar metabolism, chip color, invertase activity, and gene expression during long-term cold storage of potato (Solanum tuberosum) tubers from wild-type and vacuolar invertase silencing lines of Katahdin. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiberley-Bradford AE, Busse JS, Bethke PC. Temperature-dependent regulation of sugar metabolism in wild-type and low-invertase transgenic chipping potatoes during and after cooling for low-temperature storage. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2016;115:60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2015.12.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Guan W, Yan R, Lei J, Xu L, Wang Z. Effects of UV-C on antioxidant activity, total phenolics and main phenolic compounds of the melanin biosynthesis pathway in different tissues of button mushroom. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2016;118:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2016.03.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z, et al. Preharvest exposure to UV-C radiation: impact on strawberry fruit quality. Acta Hort. 2015;1079:589–592. doi: 10.17660/ActaHortic.2015.1079.79. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.