Abstract

The present study investigates the oxidative and thermal stability of flavoured oils developed by incorporating essential oils from black pepper and ginger to coconut oil (CNO) at concentrations of 0.1 and 1.0% (CNOP-0.1, CNOP-1, CNOG-0.1, CNOG-1). The stability of oils were assessed in terms of free fatty acids, peroxide, p-anisidine, conjugated diene and triene values and compared with CNO without any additives and a positive control with synthetic antioxidant TBHQ (CNOT). It was found that the stability of CNOP-1 and CNOG-1 were comparable with CNOT at both study conditions. The possibility of flavoured oil as a table top salad oil was explored by incorporating the same in vegetable salad and was found more acceptable than the control, on sensory evaluation. The synergetic effect of essential oil as a flavour enhancer and a powerful natural antioxidant that can slow down the oxidation of fats was established in the study.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13197-016-2446-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Coconut oil, Flavoured oil, Essential oil, Oxidative stability, Thermal stability, Antioxidant

Introduction

Vegetable oils and fats are important part of our diet as they provide energy; fat soluble vitamins and essential fatty acids required for growth and development of the body. Oils and fats, apart from providing nutrition, are known to play functional roles during product preparation contributing to the palatability of processed foods. Coconut oil is one of the widely used cooking oil in many countries like Indonesia, Srilanka, Philippines, Brazil, Thailand, Malaysia, Vietnam, and some regions of Europe and North America. The highly saturated coconut oil is unique in that it is one of the richest sources of medium chain fatty acids (MCFA) even though several controversies exist with its effect on Low density lipoprotein (LDL) (Che Man and Marina 2006). However some of the recent studies indicate that a favorable alteration in serum lipoprotein balance was achieved when coconut oil was included in the diet of healthy male volunteers (Sundram et al. 1994). Also, studies revealed that vascular disease was uncommon in Polynesian islands, where the majority of the populations consume coconut as the main source of fat (Prior et al. 1981). Beneficial effects of adding coconut kernel to diet was noticed and it was found that there were no statistically significant alterations in the total serum cholesterol level, High Density Lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol/total cholesterol ratio and LDL cholesterol/HDL cholesterol ratio of triglycerides in 64 volunteers who consumed coconut kernel rich diet (Kurup and Rajmohan 1995; Padmakumaran et al. 1998). The MCFA’s in coconut oil are similar to that of human milk and have nutraceutical benefits (Raghavendra and Raghavarao 2010). MCFA’s are important in human diet as they are reported to be inert source of energy that the human body finds it easier to metabolize and do not require energy for absorption, utilization and storage (Hiroyuki et al. 2008). Phenolic compounds namely, ferulicacid, vanillic acid, syringicacid, gallocatechin gallate, p-coumaric acid, sinapic acid and cinnamic acid, were identified from the methanolic extract of CNO (Janu et al. 2014; Marina et al. 2009).

The oxidative stability of vegetable oils is one of the key factors in determining its use in foods and their applicability in industrial situations. Several methods are developed for improving the stability of oils that includes genetic modifications, compositional changes via chemical means, addition of synthetic antioxidants like TBHQ, BHT, etc. Synthetic antioxidants are reported to be carcinogenic and BHT has been removed from GRASS list and TBHQ is banned in many countries. The search for natural antioxidants that can replace synthetic antioxidants has always has been an interesting research area among food scientists. Oleoresins and volatile oils from spices and herbs have attracted lot of attention in this regards (Tugba and Medeni 2012). Spices are considered as the major adjunct in contributing flavor to a large group of foods. Other than imparting characteristic flavor to foods, spices are rich source of antioxidant phytochemicals (Claudia and Florian 2013). The addition of spice extract or essential oil to a vegetable oil can thereby impart a combined effect as a natural antioxidant in extending the shelf life as well as a flavouring agent (Taghvaei and Jafari 2015; Sadeghi et al. 2016).

The preventive effect of cinnamon essential oil on lipid oxidation in vegetable oils was studied by Keshvari et al. (2013). The physico-chemical properties and thermal stability of olive oil flavoured by the addition of aromatic plants were studied by Ayadi et al. (2009). The essential oil of thyme, salvia and rosemary were studied for their oxidative stability towards refined oil (Sana et al. 2012). However, most of these studies were carried out by the addition of aromatic plants or plant extracts directly to vegetable oils that may lead to poor sensory characteristics on storage (Ayadi et al. 2009). Flavoured oils, obtained by the combination of both vegetable oil as well as essential oils, are attaining great importance as innovative product e.g., salad dressing and as a green product.

Essential oil from black pepper and ginger is reported to possess significant antioxidant properties (El-Ghorab et al. 2010; Kapoor et al. 2009). With this background, the present study aims to develop flavored coconut oil by incorporating black pepper and ginger essential oils and to study the shelf life and thermal stability of developed oils. As the flavoured coconut oil can be used as topping for salads, the acceptance of the developed oil as salad dressing by sensory analysis was also evaluated.

Materials and methods

Materials

Coconut oil was procured from authorized manufacturer in Kerala, India, who supply to the local markets. The oils collected were of about two weeks from manufacture date as on experimental schedule and were Agmark certified indicating their quality. Sulfuric acid, glacial acetic acid, hydrochloric acid, hexane, methanol, ethanol, iso-octane, diethyl ether, potassium iodide, sodium bicarbonate, sodium hydroxide, sodium sulphate, sodium thiosulphate, carbon tetrachloride, chloroform and tert-butyl hydroquinone (TBHQ) were obtained from SRL chemicals, India. All the chemicals used were of analytical grade.

Methods

Essential oil extraction and composition

Authenticated samples of black pepper (Panniyur) and ginger (Rajakumari) were dried to a moisture content of 5% and distilled for obtaining the essential oil following ASTA methods (1991). Hydro distillations dried and powdered spices (50 mesh size) were carried out at 100 °C for 4–6 h in a Clevenger trap. After distillation, the essential oil was passed through anhydrous sodium sulphate to remove any traces of moisture and was then collected and stored in graduated vials. The yields of essential oils were expressed as percentage (v/w). The flavor compounds in the essential oils obtained by the distillation of black pepper and ginger were analyzed by mass fragmentation pattern using Gas Chromatograph Mass Spectrophotometer (GC–MS). The GC–MS analysis was performed using GC 17A-GCMS QP 5050A combination (Shimadzu-Japan), equipped with phenyl polysil phenylene-siloxane capillary column (30 m length, 0.25 mm int. dm, 0.25 mm film thickness). The temperature of programming was set from 80 to 200 °C at the rate of 5 °C/min and held at 200 °C for 25 min. The injection temperature of 250 °C, interface temperature of 27 °C, carrier gas helium at a flow rate of 1 mL/min, mass scan range of 900 amu, ionizing electron energy of 70 eV and the inlet pressure of 100 kPa were the parameters set during the analysis. Identification of the components was achieved by comparing the retention time of authentic samples, confirmed by comparing the Kovats indices and the mass spectra of the samples with standard library-NIST-05 and library created in the laboratory (Adams 2001; Davies 1990; Jennings and Shibamoto1980). The retention indices were calculated for all constituents using a homologous series of n-alkanes, C6–C22. The percentage composition of the identified compounds was computed from the GC peak area in methyl silicon column.

Flavoured oil preparation

Black pepper and ginger essential oils were added at two concentrations (0.1 and 1.0% pepper essential oil—CNOP-0.1 and CNOP-1 respectively; 0.1 and 1.0% ginger essential oil—CNOG-0.1 and CNOG-1, respectively w/w) to coconut oil. It was blended thoroughly in a shaking water bath. The oils were then stored in glass bottles and were analyzed for oxidative and thermal stability studies.

Storage stability analysis

The flavoured oils were stored at 60 °C in a hot air oven for a period of seven weeks. A control of pure coconut oil (CNOC) and a positive control of coconut oil with synthetic antioxidant TBHQ at 200 ppm (CNOT) were also kept for study. Samples were withdrawn at intervals of seven days for analysis. Chemical and physical parameters of oils namely free fatty acid (FFA), peroxide (PV), p-anisidine values (p-Av), conjugated diene and triene values and colour were measured according to AOCS methods (1990).

Thermal stability

The thermal stability, to assess the stability of oils during frying, was analyzed by heating the oils at 180 °C for 1 h (Abdulkarim et al. 2007; Ayadi et al. 2009; Murari and Shwetha 2016). The samples were analyzed for their physico-chemical parameters (FFA, PV, p-Av, diene and triene values and colour).

Sensory evaluation

The acceptance of the developed flavoured oils as salad oil was evaluated for its sensory characteristics. The blends of flavoured oil were prepared one week prior to the sensory evaluation and were stored in sealed glass bottles for uniform mixing and stabilization of the samples. Fresh vegetables (carrot and cumber) were sliced into small cubes and salt was added to taste. It was then mixed with oil in the ratio of 10:1 w/w. Sensory evaluation was carried out by 20 panelists (4 fully trained and 16 semi trained), who were non smokers and with an age range of 25–45. The panelists were provided with vegetable salads in numbered closed vessels, so as to retain its maximum flavour. The product was evaluated for its sensory characteristics for flavour, taste, and overall acceptability using a 5-point hedonic scale (like extremely-5, like moderately-4, neither like nor dislike-3, dislike moderately-2, dislike extremely-1). The mean sensory scores for various attributes of the flavoured oils were calculated.

Statistical analysis

All the experiments were carried out in triplicates. The experimental results are expressed as mean ± SD of triplicate measurements and the results were processed using Microsoft Office Excel 2010. One way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and their statistical significance (p ≤ 0.05) carried out by Duncan’s post hoc analysis was ascertained using a computer program package (SPSS 16).

Result and discussion

Yield and composition of essential oil

The yield of essential oil from black pepper and ginger were 2.81 and 2.50%, respectively, on dry weight basis. The components of both black pepper and ginger volatile oils that are responsible for the characteristic aroma and flavor were analysed by Gas Chromatograph (GC) and GC–MS.

Chromatographic profile (Supplementary figures 1 and 2) of black pepper essential oil indicated the presence of 37 compounds contributing to 96.1% of the total essential oil composition and that of ginger oil constituted to 38 compounds which contribute to 95.76% of the total essential oil composition. The flavor compounds in black pepper oil and ginger oil, identified by GC–MS data, and their relative area percentages are presented in Table 1. The major terpene compounds in black pepper oil were found to be β-caryophyllene contributing to 15.03%. Zingiberene was the major compound identified in ginger essential oil contributing to 12.95%.

Table 1.

Components of black pepper and ginger essential oils identified by GC–MS

| Compounds | Black pepper oil | Ginger oil | Kovats index | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | α-Thujene | 0.94 ± 0.04 | 1.21 ± 0.24 | 938 |

| 2 | α-Pinene | 3.15 ± 0.27 | 0.74 ± 0.32 | 940 |

| 3 | Camphene | 4.99 ± 0.25 | 2.22 ± 0.14 | 952 |

| 4 | Sabinene | 8.5 ± 0.31 | 1.26 ± 0.15 | 976 |

| 5 | β-Pinene | 10.01 ± 0.29 | 0.91 ± 0.22 | 980 |

| 6 | β-myrcene | 8.6 ± 0.27 | – | 986 |

| 7 | β-Phellandrene | – | 2.09 ± 0.23 | 1216 |

| 8 | Nerol | – | 1.5 ± 0.15 | 1218 |

| 9 | 1–8 cineole | – | 2.35 ± 0.14 | 1228 |

| 10 | Neral | – | 4.58 ± 0.19 | 1227 |

| 11 | δ-3-carene | 3.02 ± 0.34 | 0.7 ± 0.18 | 1028 |

| 12 | d-Limonene | 5.6 ± 0.22 | – | 1030 |

| 13 | Sabinene hydrate | 1.5 ± 0.28 | – | 1072 |

| 14 | Linalool | – | 1.18 ± 0.12 | 1092 |

| 15 | Limonene oxide | – | – | 1122 |

| 16 | Terpinene 4-ol | 2.10 ± 0.17 | – | 1179 |

| 17 | α-Terpineol | 1.7 ± 0.11 | – | 1185 |

| 18 | Geraniol | – | 1.25 ± 0.21 | 1240 |

| 19 | Linalyl acetate | – | 0.75 ± 0.17 | 1244 |

| 20 | Geranial | – | 6.26 ± 0.14 | 1255 |

| 21 | δ-Elemene | 1.34 ± 0.26 | – | 1277 |

| 22 | 6-Udecanone | – | 1.04 ± 0.2 | 1281 |

| 23 | Neryl acetate | – | 2.9 ± 0.11 | 1342 |

| 24 | Geranylacetate | 0.8 ± 0.016 | – | 1380 |

| 25 | α-Cubebene | 1.1 ± 0.038 | – | 1390 |

| 26 | α-Copaene | 1.26 ± 0.032 | – | 1392 |

| 27 | β-Elemene | 2.44 ± 0.26 | – | 1403 |

| 28 | β-Caryophyllene | 15.65 ± 0.29 | – | 1427 |

| 29 | α-Bergamotene | – | 3.1 ± 0.13 | 1436 |

| 30 | β-Cedrene | – | 0.7 ± 0.15 | 1446 |

| 31 | Thujopsene | – | 0.85 ± 0.2 | 1451 |

| 32 | α-Humulene | 0.71 ± 0.014 | – | 1459 |

| 33 | β-Farnesene | 1.16 ± 0.37 | – | 1465 |

| 34 | γ-Murolene | 2.87 ± 0.18 | 2.14 ± 0.23 | 1477 |

| 35 | ar-curcumene | 1.33 ± 0.24 | 10.32 ± 0.16 | 1484 |

| 36 | Zingiberene | – | 12.95 ± 0.12 | 1487 |

| 37 | α-Farnesene | – | 2.45 ± 0.14 | 1496 |

| 38 | β-Bisabolene | – | 8.47 ± 0.32 | 1504 |

| 39 | β-Sesquiphellandrene | – | 10.28 ± 0.10 | 1515 |

| 40 | γ-Cadinene | – | 1.45 ± 0.17 | 1518 |

| 41 | Nerolidol | – | 1.52 ± 0.25 | 1524 |

| 42 | Elemol | – | 0.75 ± 0.23 | 1540 |

| 43 | Isocaryophyllene | 4.9 ± 0.41 | 2.25 ± 0.17 | 1568 |

| 44 | Eudesma-4(14) 11-diene | 3.2 ± 0.11 | 1.51 ± 0.25 | 1572 |

| 45 | [−]-Spathulenol | 1.02 ± 0.14 | – | 1576 |

| 46 | β-caryophyllene oxide | 1.09 ± 0.35 | 1.23 ± 0.22 | 1582 |

| 47 | Cedrol | 0.78 ± 0.13 | 1609 | |

| 48 | β-Eudesmol | 3.01 ± 0.17 | – | 1641 |

| 49 | β-Bisabolol | 6.04 ± 0.24 | – | 1677 |

| 50 | (Z, E)-Farnesol | 0.95 ± 0.041 | 1.81 ± 0.31 | 1699 |

| 51 | E, E, Farnesol | – | 1.53 ± 0.15 | 1749 |

| 52 | Curcumenyl acetate | – | 0.23 ± 0.11 | 1801 |

| 53 | Cinnamylcinnamate | – | 0.5 ± 0.02 | 2057 |

Results are expressed as mean ± SD of three parallel measurements

Oxidative stability at accelerated storage

Free Fatty Acid

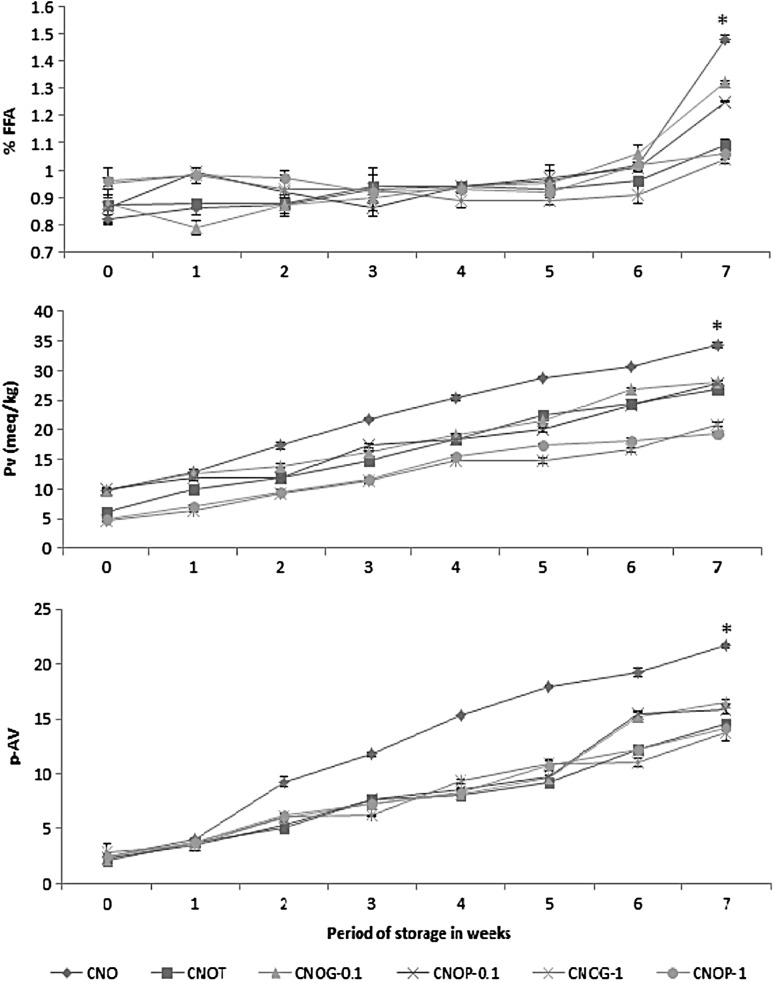

The presence of free fatty acids (FFAs) in oil is an indication of insufficient processing, lipase activity, or other hydrolytic actions. It may be noted that the initial FFA of the trial samples were slightly higher than that of the control. This may be due to the slight oxidation induced by physical blending of the oils or from the essential oil itself. On accelerated storage at 60 °C for 7 weeks, a slow and steady increase in FFA was noted in all the samples. It can be noticed that the samples showed remarkable increase in free fatty acids only after the fourth week. The FFA content increased from 0.82 ± 0.018 to 1.48 ± 0.015% in the control, whereas the control oil with synthetic antioxidant TBHQ showed an increase from 0.87 ± 0.07 to 1.09 ± 0.02 U. CNO blended with essential oil of pepper and ginger showed significantly lesser FFA formation after seven weeks of storage as compared to the control and the positive control. The FFA content increased from 0.96 ± 0.05 to 1.06 ± 0.02% in flavoured oil with 1% pepper essential (CNOP-1). In the case of flavoured oil with 1% ginger oil (CNOG-1) an increase from 0.95 ± 0.02 to 1.04 ± 0.16% was noticed. This decrease in FFA formation in flavoured oils on storage can be attributed to the ability of essential oil to slower the oxidation process. Spice essential oils are very good antioxidants (Saleh et al. 2010; Amorati et al. 2013) and this antioxidant ability of essential oils might be the reason for the lesser FFA formation in flavoured oils compared to the control oil. On a comparative basis it can be concluded that CNOP-1 and CNOG-1 were more stable than the positive control CNOT (Fig. 1a). Even though an increase in FFA was noted in all oils on storage for seven weeks, their values were within the limits of codex standards. Similar pattern was showed in the formation of FFA were garlic extract was used to stabilize sunflower oil (Shahid and Bhanger 2007).

Fig. 1.

a Free fatty acid content; b peroxide values; c p-Anisidiene values of oils on storage. (Results are expressed as mean ± SD of three parallel measurements. Asterisks statistically significant value (p ≤ 0.05) of samples from the control)

Peroxide value

The peroxide value is the most common method of assessing oxidative stability of vegetable oils. The amount of peroxides indicates the degree of primary oxidation and therefore is linked to the rancidity. The steady increase in peroxide indicates the formation of hydroperoxides during oxidation of fat. It can be noted from the Fig. 1b, that the essential oil incorporated samples had the least values for peroxides. The control oil had an initial value of 9.79 ± 0.37, a gradual increase was noted during storage and after the fourth week of storage there was significant increase to 28.86 ± 0.15 U and finally to 34.27 ± 0.44 U at the last week of storage. The peroxide value of oils at the last week of storage were 34.27 ± 0.44, 26.9 ± 0.23, 28.02 ± 0.21, 27.69 ± 0.48, 20.93 ± 0.37, 19.48 ± 0.28, respectively for CNO, CNOT, CNOG-0.1, CNOP-0.1, CNOG-1 and CNOP-1. As can be seen, CNO with essential oils of pepper and ginger at both the levels exhibited better stability as compared to the control. CNOP-0.1 and CNOG-0.1 showed values higher than TBHQ added control indicating that they are less effective than TBHQ (Fig. 1b). However, at 1% level of incorporation, both the essential oils effectively reduced the formation of peroxides indicating better stabilization of the oil, as compared to the control and positive control. This may be attributed to the radical scavenging efficiency of spice oils leading to the decreased peroxide formation. El-Ghorab et al. (2010) have studied the antioxidant activity of ginger oil towards DPPH radicals where dried ginger essential oil contributed to 83.87 ± 0.54% inhibition at a concentration of 240 µg/ml. It has been reported that the addition of spice extracts in vegetable oil reduced the peroxide value during storage (Ramadan and Wahdan 2012).

p-Anisidine value

Lipid oxidation is one of the important causes of spoilage in vegetable oils. Hydroperoxides, the major initial reaction products of lipid oxidation, are not stable and decompose spontaneously to form other compounds such as aldehydes, ketones, alcohols, acids, hydrocarbons, etc. (Rossell and Pritchard 1991). These secondary carbonyl breakdown products causing rancidity are mainly measured by the p-anisidine value. The p-Av of coconut oil blends were studied for seven weeks with control showing the maximum degradation (Fig. 1c). As compared to the control, decomposition of CNO with TBHQ and essential oils followed a similar pattern during storage. The formation of secondary oxidation product followed the order CNO ≥ CNOG-0.1 CNOP-0.1 ≥ CNOT ≥ CNOP-1 ≥ CNOG-1. As can be seen, CNOG-1 showed the maximum stability in terms of anisidine value with an initial p-Av of 2.87 ± 0.76 U and to 13.84 ± 0.88 at the last week of storage studies. The initial p-Av’s for CNOP-1 was 2.47 ± 0.02 and for CNOT was 2.12 ± 0.56 which increased gradually to 14.15 ± 0.23 and 14.60 ± 0.41, respectively, for CNOP-1 and CNOT on the 7th week of analysis. A similar report by Zaborowska et al. (2012) indicated that the p-Av values were lower in sunflower oil added with thyme extracts.

Conjugated diene and triene values

Monitoring diene conjugation emerged as a useful technique for the study of lipid oxidation. During the oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids considerable isomerization of double bonds results in the formation of hydroperoxides and this rearrangement forms conjugated dienes which exhibit an intense absorption at 234 nm (White 1991). Conjugated trienes are produced by the linolenate oxidation products or by dehydration of hydroxyl linoleate (Houhoula et al. 2002). An increase in UV absorption theoretically reflects the formation of primary oxidation products in fats and oils.

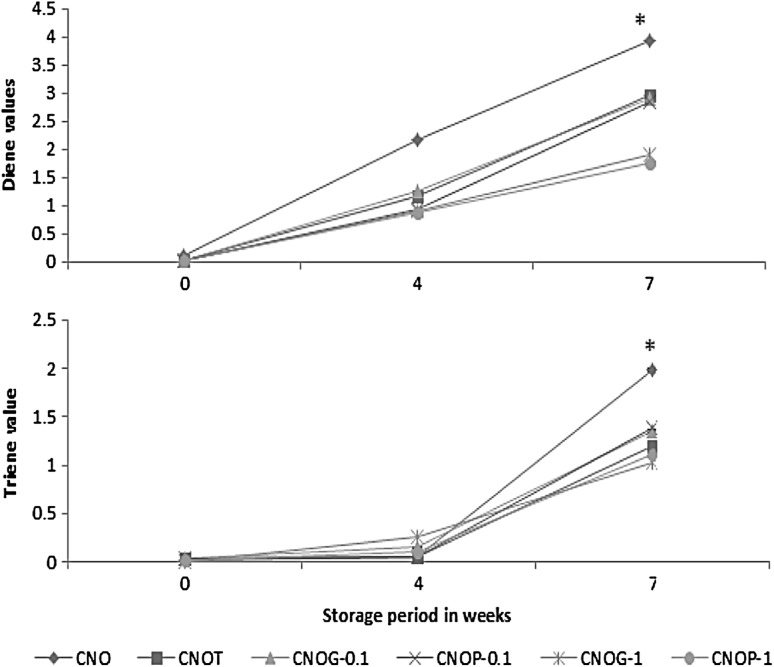

Since the unsaturated fatty acids in CNO accounts only 7–8%, the diene and triene values were less affected during storage. The triene and diene values of flavoured oils were more or less similar to CNOT. The control CNO was found to have the maximum dienes and trienes which changed from 0.098 ± 0.12 to 3.95 ± 0.11 and 0.015 ± 0.1 to 1.978 ± 0.11 (Fig. 2a, b). However in the present study, there was not much increase in dienes and trienes in flavoured oils.

Fig. 2.

a Diene values; b triene values of oils on storage. (Results are expressed as mean ± SD of three parallel measurements. Asterisks statistically significant value (p ≤ 0.05) of samples from the control)

Colour value of oils

Colour plays an important role in the acceptability of a food product. The colour of oils was measured using Lovibond tintometer (Tintometer Ltd., Sallisburry, UK), RYBN scale. The addition of essential oil to CNO resulted in an increase in R and Y values. The ginger oil and pepper oil had distinguished colour and this might have resulted in the increase in colour of oils. Among the oils, the initial colour values of flavoured oil with pepper essential oil were found to be the highest (Table 3). The Y values of both CNOP-1 and CNOG-1 were higher compared to CNO. On storage the R values showed a gradual decrease where as an increase in Y values were noted.

Table 3.

Colour of oils at different storage conditions

| Sample | Initial colour values | Colour values after storage period at 60 °C | Colour values after heating at 180 °C | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | Y | R | Y | R | Y | |

| CNO | 0.2 ± 0.01 | 1.1 ± 0.00 | 0.4 ± 0.01 | 0.8 ± 0.011 | 0.5 ± 0.01 | 2.1 ± 0.011 |

| CNOT | 0.4 ± 0.01 | 1.1 ± 0.01 | 0.1 ± 0.01 | 3.1 ± 0.013 | 0.9 ± 0.02 | 2.7 ± 0.012 |

| CNOG-0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.012 | 1.0 ± 0.01 | 0.2 ± 0.01 | 2.1 ± 0.011 | 0.7 ± 0.01 | 1.8 ± 0.012 |

| CNOP-0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.011 | 1.1 ± 0.012 | 0.1 ± 0.02 | 3.1 ± 0.01 | 0.5 ± 0.01 | 2.2 ± 0.011 |

| CNOG-1 | 0.2 ± 0.01 | 1.7 ± 0.011 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 2.6 ± 0.11 | 0.6 ± 0.02 | 2.1 ± 0.012 |

| CNOP-1 | 0.7 ± 0.01 | 1.9 ± 0.011 | 0.5 ± 0.011 | 2.3 ± 0.13 | 0.5 ± 0.01 | 2.4 ± 0.011 |

Results are expressed as mean ± SD of three parallel measurements

Thermal stability studies at frying temperature

As oils are considered as the medium for frying a large number of food products, it is very important that these oils must be thermally stable at the frying temperatures. Thermal degradation of oils at frying temperature results in a number of chemical reactions which includes hydrolysis, oxidation, thermal decomposition and polymerization (Melton et al. 1994). Prolonged heating also reduces organoleptic and nutritive quality of oils. The thermal stability of the flavoured oils at 180 °C, was evaluated in terms of FFA, PV, p-av, diene and triene values.

Free Fatty Acid

FFA’s are formed by the breakdown of triacyl glycerols on hydrolytic or autoxidation. It has been reported that on thermal processing, hydrolysis occurs more in oil with short chain fatty acids than oil with long chain saturated fatty acids. On heating at 180 °C, the flavoured oils exhibited better stability with very small increase in FFA as compared to the CNO and CNOT. CNOG-1 had the least value of 0.79 ± 0.22% and control, CNO with highest value of 0.98 ± 0.51%. Here, the result again correlated well with the previous results of storage studies, indicating the stability of flavoured oils than the control.

Peroxide value

The peroxide value showed significant change on heating at 180 °C. Among the six samples, control exhibited highest peroxide value (180 ± 0.66 U) and CNOP-1, the least. The peroxide values of the samples were 60.0 ± 0.34, 62.34 ± 0.41, 104.25 ± 0.22, 108.13 ± 0.68 and 67.05 ± 0.5 for CNOP-1, CNOG-1, CNOP-0.1, CNOG-0.1 and CNOT, respectively. The lesser PV of flavoured oil may be due to the presence of antioxidants in the essential oils of pepper and ginger that can quench the initiation and propagation steps of auto oxidation reactions. It can be noted that peroxide values of the oils heated at 180 °C was higher than that of the oils at 60 °C as the chances of formation of decomposition products are more on prolonged heating. Karoui et al. (2011), reported that there was a sharp rise in peroxides value when the temperature was raised from 25 to 180 °C during heating of corn oil. They also reported that corn oil with thyme extract showed the least peroxide value during deep frying.

p-Anisidine value

Oxidation, which is accelerated at the high temperature used in deep frying, creates rancid flavours and reduces the organoleptic characteristics of fried food. The p-Av values of coconut oil samples before and after heating at 180 °C is shown in Table 2. The pepper oil incorporated oil at 1% concentration showed the least value for p-Av, which again correlated with the peroxide value.

Table 2.

Physico-chemical parametersof coconut oil at 180 °C

| Sample | FFA—before heating | FFA—after heating | Pv—before heating | Pv—after heating | p-Av before heating | p-Av—after heating | Diene—before heating | Diene—after heating | Triene—before heating | Triene—after heating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNO | 0.82 ± 0.21 | 0.98 ± 0.51 | 9.79 ± 0.32 | 180 ± 0.66 | 2.52 ± 0.33 | 27.99 ± 0.11 | 0.021 ± 0.01 | 0.032 ± 0.01 | 0.015 ± 0.02 | 0.012 ± 0.01 |

| CNOT | 0.87 ± 0.17 | 0.80 ± 0.25 | 6.13 ± 0.24 | 67.05 ± 0.5 | 2.12 ± 0.24 | 17.23 ± 0.41 | 0.025 ± 0.01 | 0.026 ± 0.01 | 0.014 ± 0.01 | 0.030 ± 0.01 |

| CNOG-0.1 | 0.88 ± 0.29 | 0.91 ± 0.34 | 9.85 ± 0.45 | 108.1 ± 0.2 | 2.19 ± 0.41 | 17.76 ± 0.32 | 0.019 ± 0.03 | 0.020 ± 0.01 | 0.028 ± 0.02 | 0.041 ± 0.02 |

| CNOP-0.1 | 0.86 ± 0.2 | 0.82 ± 0.32 | 9.89 ± 0.61 | 104.3 ± 0.2 | 2.34 ± 0.28 | 18.13 ± 0.16 | 0.019 ± 0.01 | 0.022 ± 0.00 | 0.025 ± 0.01 | 0.021 ± 0.01 |

| CNOG-1 | 0.95 ± 0.18 | 0.79 ± 0.22 | 4.66 ± 0.34 | 62.34 ± 0.4 | 2.87 ± 0.39 | 16.64 ± 0.34 | 0.012 ± 0.02 | 0.028 ± 0.01 | 0.010 ± 0.01 | 0.031 ± 0.01 |

| CNOP-1 | 0.96 ± 0.11 | 0.83 ± 0.47 | 4.92 ± 0.38 | 60.0 ± 0.34 | 2.47 ± 0.21 | 16.52 ± 0.23 | 0.014 ± 0.01 | 0.016 ± 0.01 | 0.018 ± 0.01 | 0.030 ± 0.01 |

Results are expressed as mean ± SD of three parallel measurements

Conjugated diene and triene values at 180 °C

Neither of the samples showed a greater variation on heating indicating not much significant change compared to the control (Table 2). This may be due to the fact that the content of long chain unsaturated fatty acids in coconut oil is only 7–8%. Houhoula et al. (2002) reported that, on heating cottonseed oil, there was an increase in the conjugated dienes with frying time. These values for conjugated diene and triene reported by were much higher than that of CNO samples in the present study. The greater increase of conjugated dienes in their experiments is justified by the high content in linoleic acid (55.5%) of the cottonseed oil.

Colour value

Oil samples after heating had undergone a slight increase in its colour, it may be due to the oils instability during heating that produces many decomposition products. Similar studies in change in colour of oils were reported to the accumulation of non-volatile decomposition products such as oxidized triacyl glycerols and FFA that can lead to colour changes which indicate the extent of oil deterioration (Abdulkarim et al. 2007). The colour values of oils are given in Table 3. Heating at 180 °C, did not show much increase R values from the initial but there was remarkable change in the Y values of oils.

Spice essential oils and some of its components have been reported to possess very good antioxidant activities. The ginger essential oil components β-bisabolene, zingiberene, α-curcumene and β-caryophyllene, d-limonene, β-pinene, sabinene present in black pepper essential oil is reported to exhibit antioxidant potential (Amorati et al. 2013). The better storage and thermal stability of the flavoured oils in the present study may be attributed to the antioxidant activities of these component as well as their synergistic effect in the essential oil.

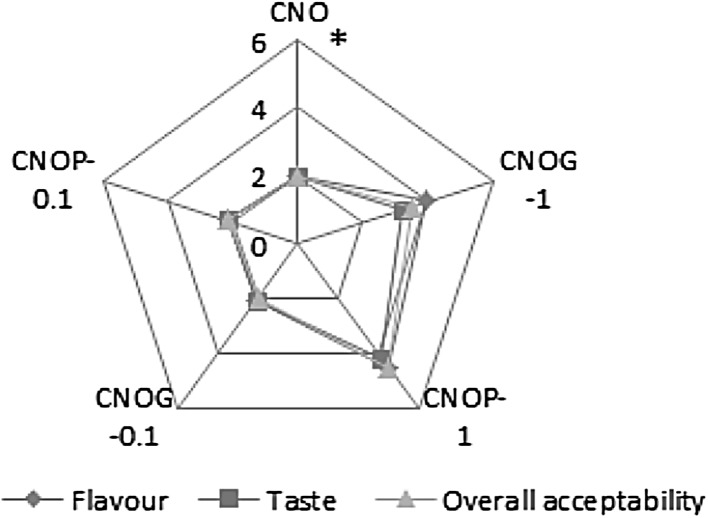

Sensory evaluation

Sensory analysis of the developed flavoured oils was carried out and compared with control by adding the flavored oils to vegetable salad. On sensory evaluation, it was found that salad with flavoured oils was preferred by the panelists. CNOP1 was found to score maximum indicating its better acceptability over other samples (Fig. 3). Among the panelists, 88% liked coconut oil flavoured with pepper essential oil, and 9% liked coconut oil flavoured with ginger oil and there was a group constituting of 3% who stood for the control without any essential oil.

Fig. 3.

Sensory evaluation of oils (Results are expressed as mean ± SD of three parallel measurements. Asterisks statistically significant value (p ≤ 0.05) of samples from the control)

Conclusion

Preservation of foods by replacement of synthetic antioxidants with natural products like essential oils and plant extracts have attained wide spread interest as a green technology deprived from any toxicity. The addition of essential oil to CNO improved its storage stability in terms of its antioxidant potential as well as its characteristic flavour attributing to the better sensory characteristics. Also as flavoured oils can be used as table top oils, the study brings out the potential use of coconut oil in a wider angle as the main source of medium chain fatty acids. The flavoured oils need no further addition of synthetic antioxidant as the study indicates good oxidative stability of CNOP1 when compared with the TBHQ added oil. The sensory analysis of the product was evaluated for colour, taste and overall acceptability. The study reveals that essential oil from black pepper and ginger could be promoted as a natural antioxidant, to improve the shelf stability of oils. The addition of essential oil as a source of natural antioxidant can definitely create an impact in the market as there is no adverse health effect on the usage of natural components. The study may be extendable to other commonly used edible oils and essential from various other spices.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge CSIR-New Delhi, India for providing the funds and facilities for carrying out the research.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Abdulkarim SM, Long K, Lai OM, Muhammad SKS, Ghazali HM. Frying quality and stability of high-oleic Moringa oleifera seed oil in comparison with other vegetable oil. Food Chem. 2007;105:1382–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.05.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adams RP. Identification of essential oil components by gas chromatography/quadrupole mass spectroscopy. Carol Stream: Allured Publishing Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Amorati R, Foti CM, Valgimigli L. Antioxidant activity of essential oils. J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61:10835–10847. doi: 10.1021/jf403496k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AOCS . Official and tentative methods of American Oil Chemist’s Society. 15. Champaign: American Oil Chemists Society Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- ASTA (1991) Official analytical methods of the American Spice Trade Association, 4th edn. Method 5, Englewood cliffs, New Jersey, pp 1–55

- Ayadi MA, Grati Kamoun N, Attia H. Physico-chemical change and heat stability of extra virgin olive oils flavoured by selected Tunisian aromatic plants. Food Chem Toxicol. 2009;47:2613–2619. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2009.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che Man YB, Marina AM. Medium chain triacyl glycerol. In: Shahidi F, editor. Nutraceutical and specialty lipids and their coproducts. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis Group; 2006. pp. 27–56. [Google Scholar]

- Claudia T, Florian CS. Stability of essential oils: a review. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2013;12:40–53. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davies NW. Gas chromatographic retention indices of monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes on methyl silicone and Carbowax 20M phases. J Chromatogr. 1990;503:1–24. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9673(01)81487-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El Ghorab AH, Nauman M, Anjum FM, Hussain S, Nadeem M. A comparative study on chemical composition and antioxidant activity of ginger (Zingiber officinale) and cumin (Cuminum cyminum) J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:8231–8237. doi: 10.1021/jf101202x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiroyuki T, Seiji S, Keiichi K, Toshiaki A. The application of medium-chain fatty acids: edible oil with a suppressing effect on body fat accumulation. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2008;17:320–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houhoula DP, Oreopoulou V, Tzai C. A kinetic study of oil deterioration during frying and a comparison with heating. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2002;79:133–137. doi: 10.1007/s11746-002-0447-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Janu C, Sobankumar DR, Reshma MV, Jayamurthy P, Sundaresan A, Nisha P. Comparative study on the total phenolic content and radical scavenging activity of common edible vegetable oils. J Food Biochem. 2014;38:38–49. doi: 10.1111/jfbc.12023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings W, Shibamoto T. Qualitative analysis of flavour and fragrance volatiles by glass capillary gas chromatography. New York: Academic Press; 1980. pp. 9–465. [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor IPS, Bandana S, Gurdip S, Heluani CSD, Lampasona MPD, Catalan CAN. Chemistry and in vitro antioxidant activity of volatile oil and oleoresins of black pepper (Piper nigrum) J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:5358–5364. doi: 10.1021/jf900642x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karoui IJ, Dhifi W, Jemia MB, Marzouk B. Thermal stability of corn oil flavoured with Thymus capitatus under heating and deep-frying conditions. J Sci Food Agric. 2011;91:927–933. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.4267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshvari M, Asgary S, Jafarian A, Najafi S, Mojtaba G. Preventive effect of cinnamon essential oil on lipid oxidation of vegetable oil. ARYA Atheros. 2013;9:280–286. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurup PA, Rajmohan T (1995) Consumption of coconut oil and coconut kernel and the incidence of atherosclerosis. In: Proceedings symposium on coconut and coconut oil in human nutrition, Coconut Development Board, Kochi, India

- Marina AM, Che Man YB, Nazimah SAH, Amin I. Antioxidant capacity and phenolic acids of virgin coconut oil. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2009;60:114–123. doi: 10.1080/09637480802549127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melton SL, Jafar S, Sykes D, Trigiano MK. Review of stability measurements for frying oils and fried food flavor. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1994;71:1301–1308. doi: 10.1007/BF02541345. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murari SK, Shwetha MV. Effect of antioxidant butylated hydroxyl anisole on the thermal or oxidative stability of sunflower oil (Helianthus Annuus) by ultrasonic. J Food Sci Technol. 2016;53:840–847. doi: 10.1007/s13197-015-2038-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padmakumaran KG, Rajamohan T, Kurup PA. Coconut kernel protein modifies the effect of coconut oil on serum lipids. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 1998;53:133–144. doi: 10.1023/A:1008078103299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prior IA, Davidson F, Salmond CE, Czochanska Z. Cholesterol Coconuts and diet on polynesian atolls: a natural experiment: the Pukapuka and Tokelau island studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 1981;34:1552–1561. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/34.8.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavendra SN, Raghavarao KSMS. Effect of different treatments for the destabilization of coconut milk emulsion. J Food Eng. 2010;97:341–347. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2009.10.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadan MF, Wahdan KMM. Blending of corn oil with black cumin (Nigella sativa) and coriander (Coriandrum sativum) seed oils: impact on functionality, stability and radical scavenging activity. Food Chem. 2012;132:873–879. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.11.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rossell JB, Pritchard JLR, editors. Analysis of oilseeds, fats, and fatty foods. New York, USA: Elsevier Applied Science; 1991. pp. 308–319. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi E, Mahtabani A, Etminan A, Karami F. Stabilization of soybean oil during accelerated storage by essential oil of ferulago angulataboiss. J Food Sci Technol. 2016;53:1199–1204. doi: 10.1007/s13197-015-2078-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh MA, Clark S, Woodard B, Deolu-Sobogun SA. Antioxidant and free radical scavenging activities of essential oils. Ethnic Dis. 2010;20:78–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sana M, Samira S, Nadia C, Ines S, Asma M, Moktar H, Manef A. Antioxidant effect of essential oils of Thymus, Salvia and Rosemarinus on the stability to auxidation of refined oils. Ann Bio Res. 2012;3:4259–4263. [Google Scholar]

- Shahid I, Bhanger MI. Stabilization of sunflower oil by garlic extract during accelerated storage. Food Chem. 2007;100:246–254. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.09.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sundram K, Hayes KC, Siru OH. Dietary palmitic acid results in lower serum cholesterol than does a lauric-myristic acid combination in normolipemic humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;59:841–846. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/59.4.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taghvaei M, Jafari SM. Application and stability of natural antioxidants in edible oils in order to substitute synthetic additives. J Food Sci Technol. 2015;52:1272–1282. doi: 10.1007/s13197-013-1080-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tugba I, Medeni M. The potential application of plant essential oils/extracts as natural preservatives in oils during processing: a review. J Food Sci Eng. 2012;2:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- White PJ. Methods for measuring changes in deep-fat frying oils. Food Technol. 1991;45:75–80. [Google Scholar]

- NIST-05 (National Institute of Standards and Technology) Library: Mass spectral data base parts 5990 ± 90150 Associated with HPGC ± MS

- Zaborowska Z, Przygoński K, Bilska A. Antioxidative effect of thyme (Thymus vulgaris) in sunflower oil. Acta Sci Pol Technol Aliment. 2012;11:283–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.