Abstract

Background and aims

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disorder associated with vascular inflammation, measured by 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (18-FDG PET/CT), and an increased risk of myocardial infarction. Patients with psoriasis are also more likely to suffer from comorbid depression. Whether depression accelerates the development of subclinical atherosclerosis in psoriasis is unknown.

Methods

Patients were selected from within a larger psoriasis cohort. Those who reported a history of depression (N = 36) on survey were matched by age and gender to patients who reported no history of psychiatric illness (N = 36). Target-to-background ratio from FDG PET/CT was used to assess aortic vascular inflammation and coronary CT angiography scans were analyzed to determine coronary plaque burden. Multivariable linear regression was performed to understand the effect of self-reported depression on vascular inflammation and coronary plaque burden after adjustment for Framingham risk (standardized β reported).

Results

In unadjusted analyses, vascular inflammation and coronary plaque burden were significantly increased in patients with self-reported depression as compared to patients with psoriasis alone. After adjustment for Framingham Risk Score, vascular inflammation (β = 0.26, p = 0.02), total plaque burden (β = 0.17, p = 0.03), and non-calcified burden (β = 0.17, p = 0.03) were associated with self-reported depression.

Conclusions

Self-reported depression in psoriasis is associated with increased vascular inflammation and coronary plaque burden. Depression may play an important role in promoting subclinical atherosclerosis beyond traditional cardiovascular risk factors.

Keywords: Psoriasis, Subclinical cardiovascular disease, Depression, Anxiety, Inflammation

1. Introduction

Psychological distress is increasingly recognized as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease [1]. Depression has been associated with cardiovascular events, subclinical atherosclerosis, and all-cause mortality independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors in a number of epidemiologic studies [2,3]. Inflammatory mediators, TNF-α and IL-6, have been shown to associate with depression in multiple investigations [4]. Furthermore, C-reactive protein, which serves as a biomarker for both inflammation and cardiovascular risk, is found to be elevated in depression [5]. These studies suggest that chronic inflammation may provide an important link between depression and cardiovascular disease.

Patients with psoriasis, a chronic inflammatory disorder, are known to experience higher rates of depression [6,7] as well as increased rates of cardiovascular events [8–12]. Recently, it was demonstrated that among patients with psoriasis, depression was associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction, stroke and cardiovascular death [13]. Because psoriasis associates with increased vascular inflammation [14], it provides a strong human clinical model to study inflammatory atherogenesis in vivo. However, whether self-reported history of depression in psoriasis relates to the development of subclinical atherosclerosis before cardiovascular events occur is unknown.

Given that patients with psoriasis have higher rates of depression, understanding the role of psychological distress in promoting inflammation-induced atherosclerotic plaque development may be important to prevent future cardiovascular events. Aortic vascular inflammation as measured by 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (18-FDG PET/CT) has proven useful for predicting cardiovascular outcomes [15], and is elevated in psoriasis [15]. Similarly, coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) provides a validated non-invasive modality for determining coronary plaque burden and composition, is predictive of cardiovascular outcomes [16], and is established for the study of coronary artery disease in psoriasis [17]. Therefore, the goal of this study was to utilize these non-invasive measures of subclinical atherosclerosis to evaluate the extent of vascular inflammation and burden of coronary artery disease associated with self-reported depression in a deeply phenotyped cohort of patients with psoriasis.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Study design

This nested cohort study was conducted using a subset of patients from a larger cohort study examining the relationship between psoriasis and cardiovascular health (NCT01778569). Approval for this research was granted by the Institutional Review Board of the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute prior to patient recruitment in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided informed consent before study participation.

2.2. Selection of study groups

Recruitment of patients via the ongoing NHLBI Protocol 13-H-0065 began January 23, 2013 and continued until October 14, 2015. All patients were over the age of [18] and had a diagnosis of psoriasis made by a dermatologist or collaborating board-certified physician. Patients who were pregnant, lactating or had kidney disease with an estimated glomerular filtration rate <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 were excluded. In a baseline medical questionnaire administered to all study participants, patients were asked to indicate whether they had a history of depression, defined and confirmed by the use of medications and/or counseling. A total of 36 patients reported a history of depression by survey. We then selected 36 age- and gender-matched patients without any reported history of psychiatric illness from the same cohort for comparison to reduce confounding by age and gender and maximize statistical efficiency.

2.3. Clinical assessment

All patients were seen at the NIH Clinical Center for visits. During these visits, patients received a detailed history and physical exam. All patients underwent 18-FDG PET/CT imaging and laboratory testing. CCTA scans were done on all patients who provided consent and lacked contraindications.

2.4. Laboratory analysis

Fasting blood samples were processed in an on-site certified clinical research laboratory. Plasma levels of markers known to associate with cardiometabolic disease and inflammation were measured –including glucose, insulin, total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, triglycerides, apolipoprotein A and apolipoprotein B –using previously published methods [15].

2.5. FDG PET/CT analysis

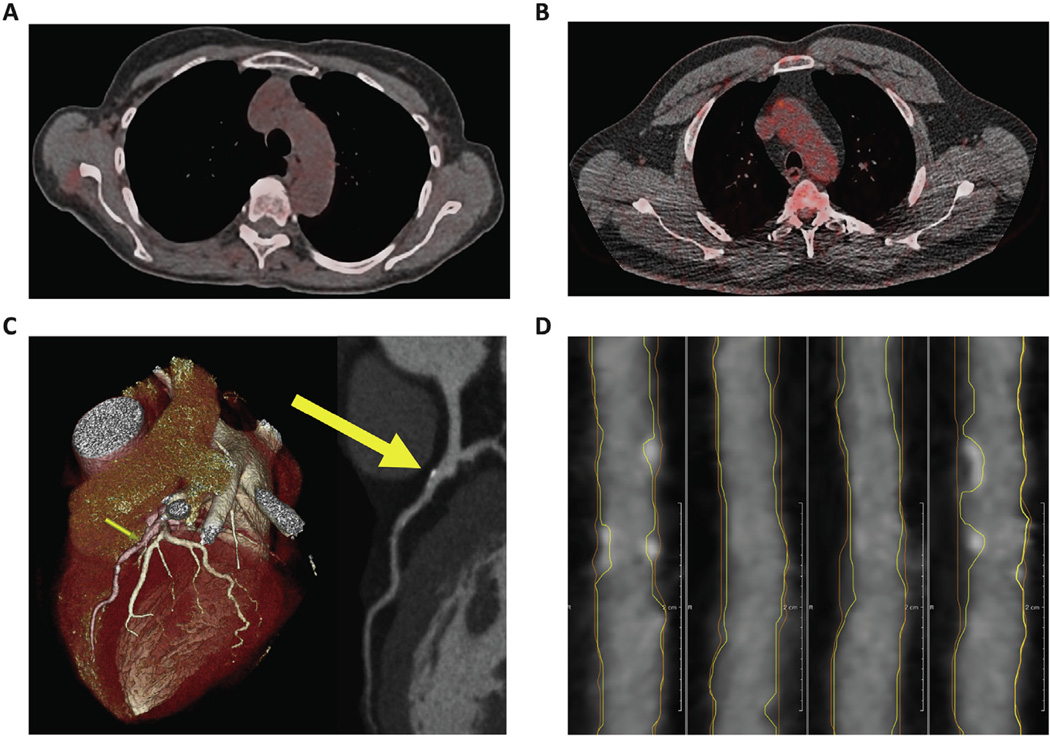

After fasting overnight, patients were given a 10 mCi dose of 18-fluorodeoxyglucose (18-FDG). Approximately 60 min after administration of 18-FDG load, PET/CT images (Fig. 1A and B) were acquired using a Siemens Biograph mCT PET/CT 64-slice scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Malvern, PA, USA). Axial 1.5 mm thick slices of the aorta were analyzed by placing regions of interest (ROIs) around the vessel walls at the level of key anatomical landmarks with careful avoidance of adjacent structures. Mean and maximum standard uptake values (SUVs) were calculated using Extended Brilliance Workspace (Phillips Electronics, NV, USA). To standardize the values, target-to-background ratios (TBR) were calculated by dividing the maximum SUVs of each slice by the 18-FDG uptake measured in the lumen of the vena cava, and we report the average TBR in the aorta for each patient.

Fig. 1. Plaque imaging by coronary CT angiography and aortic vascular inflammation by FDG PET/CT.

(A) FDG PET/CT image of a patient with psoriasis and no psychiatric history. (B) FDG PET/CT image of a patient with psoriasis and comorbid depression showing increased FDG uptake in the aortic arch indicative of higher vascular inflammation. (C) CCTA 3D reconstructed image of the same patient in Panel B showing stenosis of the left anterior descending artery corresponding with plaque on CCTA (yellow arrows). (D) Multiplanar reconstructed CCTA image of the right coronary artery of the same patient. Lines delineate the vessel wall (orange) and lumen (yellow), showing areas of increased wall volume and both calcified and non-calcified plaque. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

2.6. Coronary CT angiography analysis

Eligible patients who consented to receive CCTA were scanned on a 320 detector row unit (Aquilion ONE ViSION Edition; Toshiba Medical Systems, Otawara, Japan) using standard techniques [18,19] during their baseline visits on the same day that fasting blood samples were drawn (Fig. 1C and D). CCTA images were read and interpreted by a collaborating experienced cardiologist (MYC). We evaluated CCTA data in all patients who had analyzable scans and evaluated each coronary artery individually. Plaque morphology and composition were then analyzed for the left main, left anterior descending, left circumflex and right coronary arteries using the dedicated software program, QAngio CT (Medis, The Netherlands). Total, non-calcified, and dense calcified plaque burden were quantified on the basis of pre-defined Hounsfield unit ranges. Indices for total, non-calcified and dense calcified plaque burden were then calculated by dividing the plaque volume of each vessel by its total length, attenuated for luminal intensity. We report total burden, non-calcified and dense calcified burden for each patient.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Summary statistics were reported and data were assessed for normality by skewness and kurtosis. Normally distributed continuous variables were analyzed using the Student’s t-test. Continuous variables that were not normally distributed were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Dichotomous variable comparisons were performed using Fisher’s exact test. Univariable regression analyses were performed using TBR as a primary outcome and depression status as an independent variable. In the same fashion, univariable regression analyses were performed using total and non-calcified plaque burden as secondary outcomes and depression status as the independent variable. Multivariable linear regression analyses were performed between depression status and TBR, and between depression status and total and non-calcified plaque burden, adjusting for established cardiovascular risk factors in the form of Framingham risk scores. We reported beta coefficients and p-values for all of the regression models. All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA 12.1 statistical software (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Patient characteristics

We compared 36 psoriasis patients with a self-reported history of depression to 36 age- and gender-matched controls with psoriasis and no self-reported history of depression or other psychiatric condition (Table 1). Overall, patients in this study were middle-aged (average age of 48.9 years), equally distributed by gender, and had low cardiovascular risk by Framingham scores. Both groups had mild-to-moderate psoriasis by Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score (median 5.8, IQR 2.9–12.8). The groups did not differ significantly by major clinical parameters, namely psoriasis severity and cardiovascular risk factors.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study groups.

| Parameters | Psoriasis with depression N = 36 | Psoriasis without depression N = 36 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics and clinical history | |||

| Age (years) | 48.7 ± 12.4 | 49.0 ± 12.3 | matched |

| Males, N (%) | 18 (50%) | 18 (50%) | matched |

| Body Mass Index | 30.0 ± 6.6 | 28.5 ± 4.7 | 0.13 |

| Metabolic syndrome, N (%) | 12 (33%) | 5 (14%) | 0.05 |

| Hypertension, N (%) | 13 (36%) | 7 (19%) | 0.11 |

| Type 2 diabetes, N (%) | 3 (8%) | 3 (8%) | 1.00 |

| Hyperlipidemia, N (%) | 17 (47%) | 17 (47%) | 1.00 |

| Current tobacco use, N (%) | 7 (19%) | 7 (19%) | 0.17 |

| Personal history of CAD, N (%) | 2 (6%) | 3 (8%) | 0.64 |

| Family history of CAD, N (%) | 11 (31%) | 15 (42%) | 0.33 |

| Exercise frequency ≥ once weekly, N (%)a | 29 (88%) | 29 (94%) | 0.44 |

| Cardiovascular risk profile | |||

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 125.5 ± 19.0 | 120.2 ± 14.7 | 0.10 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 74.1 ± 10.2 | 71.3 ± 10.3 | 0.13 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 4.79 ± 1.03 | 4.57 ± 0.99 | 0.18 |

| LDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 2.75 ± 0.84 | 2.56 ± 0.79 | 0.17 |

| HDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 1.35 ± 0.42 | 1.44 ± 0.43 | 0.17 |

| Framingham Risk score [median (IQR)] | 4 (1–6) | 2.5 (1–5) | 0.56 |

| Hs-CRP, nmol/L [median (IQR)] | 20.95 (9.71–41.43) | 22.86 (6.67–62.86) | 0.84 |

| Psoriasis characteristics | |||

| Disease duration, years | 22.3 ± 15.5 | 20.5 ± 15.3 | 0.31 |

| Body surface area affected, % [median (IQR)] | 4.5 (2.8–17.4) | 3.4 (1.7–13.2) | 0.34 |

| PASI score [median (IQR)] | 6.3 (3.2–13.7) | 4.7 (2.8–12.8) | 0.25 |

| Systemic or biologic therapy, N (%) | 12 (33%) | 14 (39%) | 0.62 |

Continuous variables are expressed as Mean ± Standard Deviation unless specified otherwise.

Hs-CRP = High sensitivity C-reactive protein, PASI = Psoriasis Area and Severity Index.

N = 33 vs. 31.

3.2. Vascular inflammation by FDG PET/CT

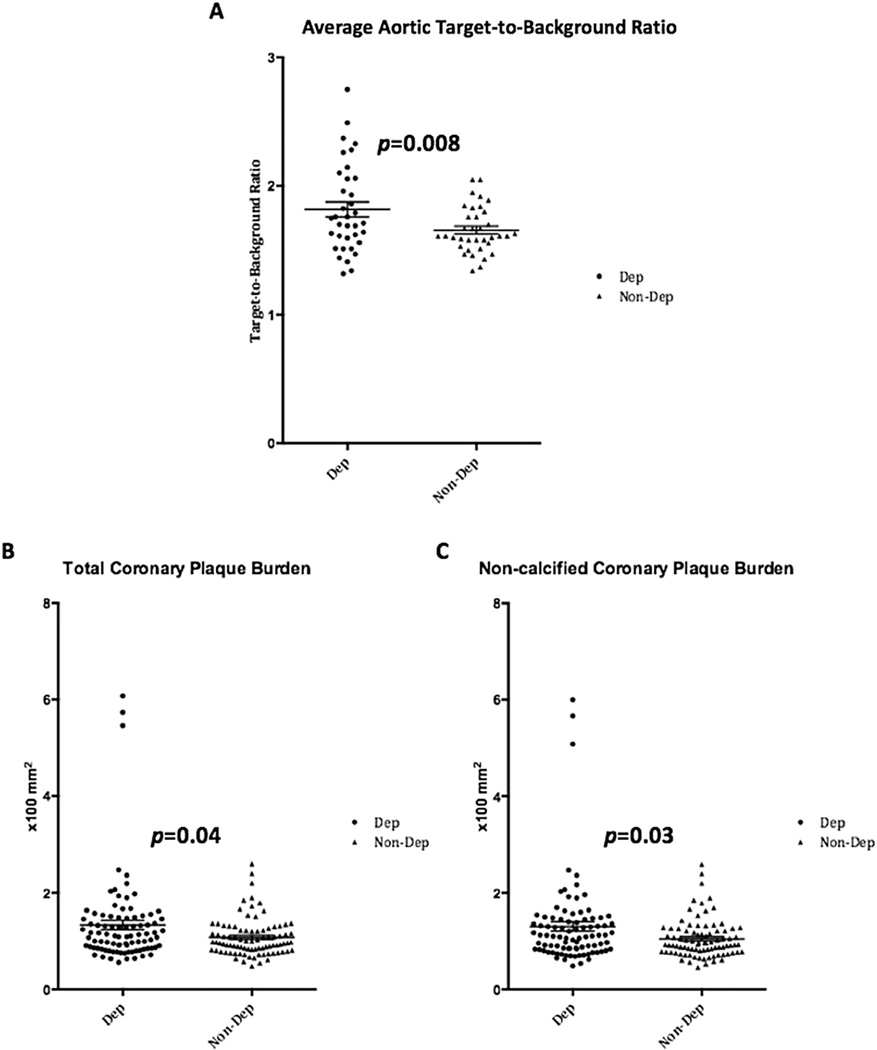

Vascular inflammation (by TBR) was significantly higher in the group with self-reported depression (Fig. 2 & Table 2A). These differences remained significant after adjustment for Framingham risk score (Table 3A). Stratified analysis showed that the use of systemic and biologic therapies eliminated the observed relationship between depression status and vascular inflammation. In the absence of systemic and biologic therapies, a stronger relationship existed between depression status and vascular inflammation (Table 4).

Fig. 2. Aortic vascular inflammation and coronary plaque burden by depression status.

Scatter dot plots of individual participants demonstrate significantly higher (A) average aortic target-to-background ratio, (B) total coronary plaque burden, and (C) non-calcified plaque burden values in participants with self-reported depression (Dep) as compared to those without self-reported depression (Non-Dep).

Table 2. Non-invasive markers of subclinical atherosclerosis.

(A) Vascular inflammation by depression status. (B) Coronary plaque burden by depression status.

| Parameter | Comorbid depression | No psychiatric history | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | |||

| Vascular inflammation by FDG-PET/CT | |||

| Total aortic TBR | 1.82 ± 0.34 | 1.66 ± 0.18 | 0.008 |

| Aortic arch TBR | 1.98 ± 0.36 | 1.84 ± 0.21 | 0.02 |

| Descending aortic TBR | 1.81 ± 0.37 | 1.65 ± 0.18 | 0.01 |

| Suprarenal aortic TBR | 1.90 ± 0.42 | 1.69 ± 0.24 | 0.007 |

| Infrarenal aortic TBR | 1.79 ± 0.40 | 1.59 ± 0.19 | 0.003 |

| B | |||

| Plaque burden adjusted for luminal attenuation | |||

| Total burden (×100), mm2 [median (IQR)] | 1.11 (0.85–1.49) | 0.98 (0.81–1.22) | 0.04 |

| Non-calcified burden (×100), mm2 [median (IQR)] | 1.10 (0.83–1.45) | 0.93 (0.78–1.21) | 0.03 |

| Dense calcified burden (×100), mm2 [median (IQR)] | 0.01 (0.005–0.03) | 0.01 (0.003–0.03) | 0.37 |

TBR = Target-to-Background Ratio.

Table 3. Multivariate analyses of vascular inflammation and coronary plaque burden by depression status.

(A) Relationship between vascular inflammation and depression status. (B) Relationship between coronary plaque burden and depression status.

| Model | β (p value) |

|---|---|

| A | |

| Total aorta | |

| Unadjusted | 0.28 (0.02) |

| Adjusted for FRS | 0.26 (0.02) |

| Aortic arch | |

| Unadjusted | 0.25 (0.04) |

| Adjusted for FRS | 0.23 (0.047) |

| Descending aorta | |

| Unadjusted | 0.27 (0.02) |

| Adjusted for FRS | 0.25 (0.03) |

| Suprarenal aorta | |

| Unadjusted | 0.29 (0.01) |

| Adjusted for FRS | 0.27 (0.02) |

| Infrarenal aorta | |

| Unadjusted | 0.32 (0.007) |

| Adjusted for FRS | 0.30 (0.01) |

| B | |

| Total plaque burden | |

| Unadjusted | 0.18 (0.02) |

| Adjusted for FRS | 0.17 (0.03) |

| Non-calcified burden | |

| Unadjusted | 0.18 (0.02) |

| Adjusted for FRS | 0.17 (0.03) |

Table 4. Stratified analysis of use of systemic/biologic therapies.

(A) Vascular inflammation, coronary plaque burden and depression status relationship stratified by systemic/biologic. (B) Multivariate analyses stratified by systemic/biologic therapy use therapy use.

| A | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | No systemic/biologic (N = 46) | Systemic/biologic (N = 26) | ||||

| Dep (N = 24) | No dep (N = 22) | p value | Dep (N = 12) | No dep (N = 14) | p value | |

| Aortic TBR | 1.85 ± 0.37 | 1.61 ± 0.14 | 0.003 | 1.75 ± 0.28 | 1.73 ± 0.21 | 0.42 |

| Total plaque burden | 1.46 ± 1.12 | 1.05 ± 0.35 | 0.006 | 1.11 ± 0.32 | 1.11 ± 0.46 | 0.49 |

| Non-calcified burden | 1.42 ± 1.10 | 1.02 ± 0.36 | 0.006 | 1.09 ± 0.31 | 1.09 ± 0.46 | 0.49 |

| B | ||

|---|---|---|

| Model | No systemic/biologic | Systemic/biologic |

| β (p value) | β (p value) | |

| Relationship between aortic vascular inflammation and self-reported depression | ||

| Unadjusted | 0.39 (0.007) | 0.04 (0.84) |

| Adjusted for FRS | 0.40 (0.007) | −0.09 (0.64) |

| Adjusted for FRS and PASI score | 0.30 (0.03) | −0.11 (0.57) |

| Relationship between total plaque burden and self-reported depression | ||

| Unadjusted | 0.24 (0.01) | 0.002 (0.98) |

| Adjusted for FRS | 0.23 (0.02) | −0.03 (0.79) |

| Adjusted for FRS and PASI score | 0.23 (0.02) | −0.07 (0.62) |

| Relationship between non-calcified plaque burden and self-reported depression | ||

| Unadjusted | 0.24 (0.01) | 0.002 (0.98) |

| Adjusted for FRS | 0.23 (0.01) | −0.04 (0.78) |

| Adjusted for FRS and PASI score | 0.23 (0.02) | −0.07 (0.61) |

Dep = Self-reported Depression.

FRS = Framingham Risk Score, PASI = Psoriasis Area and Severity Index.

3.3. Coronary plaque burden by coronary CT angiography

Total and non-calcified coronary plaque burden were significantly higher in patients with self-reported depression (Fig. 2 & Table 2B). The relationship of total and non-calcified coronary plaque burden to depression status remained significant after adjustment for Framingham risk score (Table 3B). Stratified analysis showed that the use of systemic and biologic therapies eliminated the observed relationship between depression status and coronary plaque burden. In patients not on systemic or biologic therapies, stronger relationships existed between depression status and total and non-calcified coronary plaque burden (Table 4).

4. Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate: 1) among patients with psoriasis, those with self-reported depression have increased vascular inflammation as quantified by 18-FDG PET/CT; 2) coronary plaque burden, as assessed by CCTA, the gold-standard non-invasive modality for assessing coronary plaque, is significantly higher in patients with psoriasis who report having depression than in those with psoriasis alone, and 3) the observed associations of vascular inflammation and coronary plaque burden with comorbid depression in psoriasis persist beyond adjustment for traditional CVD risk factors, as assessed by Framingham risk. Additionally, using stratified analysis we show that the observed relationships between markers of subclinical atherosclerosis and self-reported depression are stronger in the absence of systemic or biologic treatment and do not retain significance in the presence of such treatments. Thus, our findings suggest that patients with psoriasis –already at increased cardiovascular risk due to chronic inflammation– may have even higher cardiovascular risk associated with self-reported psychiatric comorbidities that is not fully captured by Framingham risk score. These findings suggest that psoriasis patients with a history of depression should be carefully screened for CVD risk factors.

For several decades depression has been studied as a cardiovascular risk factor [20,21]. Studies have correlated the presence of depression with myocardial infarction, stroke and sudden death [2,3]. As both depression and anxiety have been implicated in atherosclerosis, though admittedly with different magnitudes of effect, we chose to include patients who reported both depression and anxiety in this study rather than excluding them. However, it should be noted that causal pathways are complex and proposed mechanisms differ between depression and anxiety with regards to their contribution to atherosclerotic disease.

In recent years, there has been a greater focus on early measures of cardiovascular disease using non-invasive markers, allowing us to better understand the atherosclerotic process before devastating adverse cardiovascular events occur. As a result, validated noninvasive imaging techniques such as FDG PET/CT and CCTA are useful tools that are being increasingly applied to study subclinical atherosclerotic disease. The evidence base for using these imaging modalities to examine the effects of psychological factors on cardiovascular health is small but demonstrates detectable differences which may portend adverse future prognosis. Our findings in a chronic inflammatory cohort show that both vascular inflammation and coronary plaque burden are increased by self-reported depression beyond what can be attributed to traditional cardiovascular risk, providing further support for the link between psychological distress and coronary artery disease.

Our work provides the first study of subclinical atherosclerosis via multimodal imaging in psoriasis patients with depression. We utilize two different validated imaging methods to show that self-reported depression associates with increased aortic vascular inflammation and progression of early coronary artery disease in psoriasis, beyond what is seen to associate with traditional risk factors. Furthermore, this study draws from a large, well-phenotyped cohort of psoriasis patients, allowing for in-depth profiling of cardiovascular risk factors.

Limitations of this study include its small sample size, its cross-sectional nature, and its inability to use inventories for better characterization of depression status in conjunction with baseline scans. For both vascular inflammation by TBR and coronary plaque burden, we observed appreciable overlap in values between groups likely due to the small sample size in our study. Larger, longitudinal studies are warranted to provide more support for the observed association between psychiatric comorbidities and coronary artery disease in patients with chronic inflammation, and to allow for adequate comparison of key inflammatory mediators that have been implicated, such as TNF-α and IL-6 [5], as well as other biomarkers involved in stress-related pathways. We used patient self-reporting at the time of the baseline visit to categorize patients as having or not having comorbid depression. As such, patient categorization is subject to inherent biases associated with self-reporting. Future investigations should incorporate the use of a self-rating depression scale to better expound upon these initial findings. Despite these limitations, our novel FDG PET/CT and CCTA findings merit further investigation.

In conclusion, we show that self-reported depression in psoriasis is associated with increased vascular inflammation and coronary artery disease, as assessed by FDG PET/CT and CCTA, respectively. Our findings suggest a role for depression in the development of subclinical atherosclerosis, beyond what is attributable to traditional cardiovascular risk factors, although causation cannot be determined in this study and future studies are needed. Additionally, our work highlights that patients with psoriasis and self-reported depression may be a particularly vulnerable population for the development of coronary artery disease and consequent cardiovascular events. This risk may not be completely captured by conventional prognostication in the form of Framingham risk score calculation. Patients with chronic inflammatory diseases, such as psoriasis, may benefit from better risk stratification and care that is inclusive of screening for depression in order to reduce cardiovascular diseases.

Acknowledgments

In the previous 12 months, Dr. Gelfand served as a consultant for Abbvie., Astrazeneca, Celgene Corp, Coherus, Eli Lilly, Janssen Biologics (formerly Centocor), Sanofi, Merck, Novartis Corp, Endo, Valeant, and Pfizer Inc., receiving honoraria; and receives research grants (to the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania) from Abbvie, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis Corp, Regeneron, and Pfizer Inc.; and received payment for continuing medical education work related to psoriasis. Dr. Gelfand is a co-patent holder of resiquimod for treatment of cutaneous T cell lymphoma.

Financial support

This study was supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Intramural Research Program (HL006193-02), R01-HL111293, and K24 AR064310 and National Psoriasis Foundation Discovery Grant.

This research was made possible through the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Medical Research Scholars Program, a public-private partnership supported jointly by the NIH and generous contributions to the Foundation for the NIH from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, The American Association for Dental Research, The Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and the Colgate-Palmolive Company, as well as other private donors.

For a complete list, please visit the Foundation website at: http://fnih.org/work/education-training-0/medical-research-scholars-program.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors confirm that there are no other potential conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

All authors had access to the data and meet requirements for authorship of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Brotman DJ, Golden SH, Wittstein IS. The cardiovascular toll of stress. Lancet. 2007;370:1089–1100. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61305-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61305-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alcantara C, Muntner P, Edmondson D, et al. Perfect storm: concurrent stress and depressive symptoms increase risk of myocardial infarction or death. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes. 2015;8:146–154. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.114.001180. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.114.001180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barefoot JC, Schroll M. Symptoms of depression, acute myocardial infarction, and total mortality in a community sample. Circulation. 1996;93:1976–1980. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.11.1976. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.93.11.1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dowlati Y, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, et al. A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biol. Psychiatry. 2010;67:446–457. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.033. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hughes MF, Patterson CC, Appleton KM, et al. Predictive value of depressive symptoms for all-cause mortality: findings from the prime belfast study examining the role of inflammation and cardiovascular risk markers. Psychosom. Med. 2016 doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000289. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jensen P, Ahlehoff O, Egeberg A, Gislason G, Hansen PR, Skov L. Psoriasis and new-onset depression: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2015 doi: 10.2340/00015555-2183. http://dx.doi.org/10.2340/00015555-2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurd SK, Troxel AB, Crits-Christoph P, Gelfand JM. The risk of depression, anxiety, and suicidality in patients with psoriasis: a population-based cohort study. Arch. Dermatol. 2010;146:891–895. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.186. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archdermatol.2010.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Armstrong EJ, Harskamp CT, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis and major adverse cardiovascular events: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000062. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000062. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.113.000062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehta NN, Yu Y, Pinnelas R, et al. Attributable risk estimate of severe psoriasis on major cardiovascular events. Am. J. Med. 2011;124:775, e771–e776. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.03.028. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gelfand JM, Neimann AL, Shin DB, Wang X, Margolis DJ, Troxel AB. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis. Jama. 2006;296:1735–1741. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.14.1735. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.14.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahlehoff O, Gislason GH, Charlot M, et al. Psoriasis is associated with clinically significant cardiovascular risk: a Danish nationwide cohort study. J. Intern. Med. 2011;270:147–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02310.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li WQ, Han JL, Manson JE, et al. Psoriasis and risk of nonfatal cardiovascular disease in U.S. women: a cohort study. Br. J. Dermatol. 2012;166:811–818. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10774.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10774.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egeberg A, Khalid U, Gislason GH, Mallbris L, Skov L, Hansen PR. Impact of depression on risk of myocardial infarction, stroke and cardiovascular death in patients with psoriasis: a Danish nationwide study. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2015 doi: 10.2340/00015555-2218. http://dx.doi.org/10.2340/00015555-2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naik HB, Natarajan B, Stansky E, et al. Severity of psoriasis associates with aortic vascular inflammation detected by FDG PET/CT and neutrophil activation in a prospective observational study. Arteriosclerosis Thrombosis Vasc. Biol. 2015;35:2667–2676. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306460. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Figueroa AL, Abdelbaky A, Truong QA, et al. Measurement of arterial activity on routine FDG PET/CT images improves prediction of risk of future CV events. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2013;6:1250–1259. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.08.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chow BJ, Wells GA, Chen L, et al. Prognostic value of 64-slice cardiac computed tomography severity of coronary artery disease, coronary atherosclerosis, and left ventricular ejection fraction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010;55:1017–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.039. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hjuler KF, Bottcher M, Vestergaard C, et al. Increased prevalence of coronary artery disease in severe psoriasis and severe atopic dermatitis. Am. J. Med. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.05.041. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salahuddin T, Natarajan B, Playford MP, et al. Cholesterol efflux capacity in humans with psoriasis is inversely related to non-calcified burden of coronary atherosclerosis. Eur. heart J. 2015 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv339. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwan AC, May HT, Cater G, et al. Coronary artery plaque volume and obesity in patients with diabetes: the factor-64 study. Radiology. 2014;272:690–699. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14140611. http://dx.doi.org/10.1148/radiol.14140611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anda R, Williamson D, Jones D, et al. Depressed affect, hopelessness, and the risk of ischemic heart disease in a cohort of U.S. adults. Epidemiology. 1993;4:285–294. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199307000-00003. PMID: 8347738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rugulies R. Depression as a predictor for coronary heart disease. a review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2002;23:51–61. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00439-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00439-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]