Abstract

The sensory analysis of new products is essential for subsequent acceptance by consumers, moreover in the functional food market. The acceptance and food neophobia of cooked sausages formulated with cactus pear fiber or pineapple pear fiber, as functional ingredient, was complemented with a sensory characterization by R-index and qualitative descriptive analysis (QDA). Female consumers aged between 40 and 50 years showed greater interest in the consumption of healthy foods, with a higher level of food neophobia towards pineapple fiber sausages. R-index for taste was higher in pineapple fiber samples. Cactus pear fiber samples presented higher R-index score for texture. In QDA, color, sweet, astringent and bitter flavors, pork meat smell and a firm and plastic texture were significant, with a good relationship (38%) between the evaluated attributes. Sensory attributes are important on the acceptance and neophobia of functional foods like cooked sausages with fruit peel fiber as functional ingredient.

Keywords: Functional foods, Food neophobia, Healthy foods, R-index, QDA

Introduction

Meat products play an important role in human nutrition, due to protein, fat and other nutrients content. However, excess intake of these products has been linked to various diseases such as hypertension and obesity (Weiss et al. 2010). Dietary fiber is a compound derived mainly from fruit peels, vegetables and cereals with different functional properties depending on the source and type of processing (Cáprita et al. 2010). The peel of cactus pear fruit contains functional and bio-active compounds, such as total dietary fiber of 64.15%, higher than the fruit peels of banana, apple, mango, carrot, maguey leaf and grapefruit albedo (Chávez-Zepeda et al. 2009), in addition to having good antioxidant activity (89%) (Díaz-Vela et al. 2013). Pineapple, a fruit of the Bromeliaceae family, is one of the most produced fruits worldwide, and peel contains a high level of total dietary fiber (62.54%) (Chávez-Zepeda et al. 2009). The dietary fiber present in the peel of the fruit has been considered a functional ingredient in the formulation of meat products due to its water holding capacity and decreased cooking loss (Garcia et al. 2002).

There are several approaches to determine the level of acceptance of new food products, such as determining the level of food neophobia, R-index and quantitative descriptive analysis. The study of food neophobia has been developed to quantify and classify the level of fear among consumers in their tendency to approach or avoid new foods (Pliner 1994). This analysis has been used in recent years to determine the degree of acceptance of new foods before processing and consumption (Schnettler et al. 2013). The R-Index parameter is a measure of sensitivity indicating the probability that a judge can distinguish between an experimental condition (the presence of the signal) and another (the absence of this signal or the presence of another). The R-Index estimates the percentage of pairwise comparisons that are correctly evaluated by the judges according to the desired signal (O’Mahony 1979, 1983). In same manner, quantitative descriptive analysis is considered a way of characterizing a product, where the defined terminology is obtained through the appropriate analysis of the sensory attributes of the food (Stone and Sidel 1985).

The understanding of sensory responses on the acceptance of fiber-enriched foods validates the promotion of the healthy effect of these types of foods (Grigor et al. 2016). In this view, in the development of healthier foods (this is, added fiber) the consumers perception and the sensory characteristics are important features to determinate in order to ensure the consumers’ acceptance of healthy foods. The aim of this study was to determine the effect of cactus pear (Opuntia ficus indica) or pineapple (Ananas comosus) fiber as techno-functional ingredient, fiber source, on the acceptability, neophobia and sensory characteristics of cooked sausages.

Materials and methods

Cooked sausages preparation with added fiber

Cactus pear fiber and pineapple fiber were obtained according to the method reported by Díaz-Vela et al. (2013). Cactus pear (Opuntia ficus) peel and pineapple (Ananas comosus) peel were recovered from local fresh fruit establishments located in Ecatepec, north of Mexico City, from May to August, 2011. The cactus pear season runs from April to September, and pineapple is produced all year in Mexico. Peels were collected weekly and transported to university campus in plastic boxes (approximately 2 kg each), washed in cold tap water and stored under refrigeration (5 ± 1 °C) until processing. Fruit peels were equilibrated at room temperature for 2 h before being cut into 2 × 2 cm pieces and dried at 60 °C for approximately 24 h in an air convection oven (Craft Instrumentos Científicos, México City). The dried peels were ground in a mill and sieved consecutively with mesh sizes Nos. 100, 80, 50 and 20 sieves to obtain a regular and homogeneous powder named fiber. Cactus pear and pineapple fibers were stored in dark containers until use.

The sausages were prepared with added fiber adapting the formulation and procedure reported by Diaz-Vela et al. (2015). Lean pork and lard were purchased in local abattoirs, and visible fat and connective tissue were removed. The meat (50% w/w) was ground through a 0.42-cm plate in a meat grinder and mixed with salt (2% w/w), Hamine® commercial phosphate mixture (McCormick-Pesa, Mexico City, Mexico, 0.8% w/w) curing salt (0.3% w/w) with half of the total ice for one min in a Moulinex DPA2 Food Processor (Moulinex, Ecully, France). Frozen lard (pork back fat) was added and emulsified for two more min. Frozen temperature was −4 °C, the commercial temperature obtained in domestic freezers, the lard was previously cut in small cubes before be frozen. Firm pork fats with high melting point are the most adequate for sausage production. Raw meats and fats are chopped and comminuted in a grinder under cold temperatures. The size of lean and fat particles will depend on the plate size during grinding (Toldrá and Reig 2007). The rest of the ice was added and emulsified for 2–3 min, adding wheat flour (5% w/w) until total ingredient incorporation. Cactus pear fiber or pineapple fiber was added (2%, w/w) for different treatments; where there was no added fiber the treatment was considered as control. Batters were stuffed into 20-mm diameter cellulose casings and cooked in a water bath until reaching an internal temperature of 70 ± 2 °C (about 15 min) and cooled in an ice bath. The sausages were vacuum packed and stored at 4 °C until subsequent analysis.

Consumer attitude to healthy foods and food neophobia

Consumer interest for healthy food and food neophobia were determined for the same group of consumers (278 people, 214 women and 64 men aged 30–50 years). Their interest for nutritional healthy eating was determined using the General Health Interest Questionnaire (Roininen et al. 1999, 2001). A card was provided with information about the benefits of fiber, how fruit peels are a source of fiber, and functional food (dietary fiber: vegetable or fruit substance that improves health by promoting the growth of beneficial bacteria, in addition to helping cholesterol and blood glucose reduction. Cactus pear peel/pineapple peel: Important source of dietary fiber and antioxidant. Functional food: food that contains a nutrient with beneficial health effects). The food neophobia scale consisted of 10 statements about eating habits with five graded responses from “completely disagree” (5 points) to “completely agree” (1 point). Half of the statements were written in reverse relationship to food neophobia, considering responses in the reverse value (“completely disagree” 1 point, “completely agree” 5 points). The food neophobia score was calculated as the sum of the responses with a theoretical range from 10 to 50.

R-index

A total of thirty judges, who consume sausages frequently, were recruited at the university campus. Differences in sausage firmness after incorporation of the fiber were evaluated by R-index ranking. The control (sausage formulated with no cactus pear fiber or pineapple fiber) and tested sausages with fiber (cactus pear fiber or pineapple fiber) were randomly coded with a random three digit number (two of each one) and presented to judges (at room temperature) who were asked to order the samples according to the perceived firmness from 1 (less firm) to 4 (more firm), and whether they were ‘sure’ or ‘unsure’ about their decision. Differences in sausage taste due to fiber incorporation were evaluated by R-index rating. Two different standard samples (one control without added fiber and another one with added fiber) were presented to judges as reference. Six randomly encoded samples (3 control, 3 with added fiber) were provided and judges were asked to classify the samples as control (no added fiber) or samples with added fiber, and whether they were ‘sure’ or ‘unsure’ about their decision. The presentation also should be random by using a compilation of random numbers, where assign three-digit random code numbers to each sample ensure mask the samples identity (Stone and Sidel 1985, 2004). Responses in both tests were computed and simplified calculating the signal detection index (O’Mahony 1992). The category “Different from control, sure (S)” was created from the combined “Sure” responses for ‘lesser and ‘higher’ firmness than control. The category “Different, unsure (S?)” was created from the combined “Unsure” responses for ‘lesser and ‘higher’ firmness than control. The number of evaluations for each sample for firmness or taste was the total number of judges (30). The level of significance was determined using tables of critical values for one-tailed tests (Bi and O’Mahony 1995).

Quantitative descriptive analysis

Complete sensory attributes descriptors of the added fiber sausages were obtained using the quantitative descriptive analysis (QDA) (Stone and Sidel 2004). Twelve panelists were recruited to participate in the sensitivity screening tests based on the consumption of cooked sausages, interest in the test, and verbal/social skills. The group of twelve was given a discrimination test and the ten highest performers were selected to continue with the QDA training. In a posterior session, with a QDA moderator, the panelists developed 29 sensory terms (attributes) to describe cooked sausages. The different attributes and their respective descriptors used for the evaluation of the samples were: appearance: color, shiny, homogeneous, compact; odor: chicken soup, smoked, sweet, cooked, pork meat, fermented, rancid; taste: salty, sweet, smoked, rancid, spicy, cooked, fatty, pork meat, astringent, bitter, chicken soup; and texture: firm, plasticky, greasy, fibrous, rubbery, moist. The QDA was performed in two sessions. Each panelist received three randomly coded sausage samples (approx. 2 × 2 cm) of each treatment: control, cactus pear flour and pineapple flour. Each panelist rated the attributes of each sample on a 15 cm semi-structured line scale Compusense® five sensory evaluation software (Compusense, Ontario, Canada). A skillful moderator working with a well/designed guide can rapidly elicit much information and many descriptive terms about the product. A professional moderator is responsible for managing the process, starting from a general introduction and then directing the participants’ conversation to a particular topic, eventually to discuss the specific idea, type of product, or specific features that might be incorporated into a product. During the course of 2 h discussion on frankfurters consumers came with a variety of descriptive terms and phrases dealing with such diverse topics as “heritage” of the frankfurters, and sensory terms which emerged from the group discussions (Stone and Sidel 2004).

Statistical analysis

In determining the rate of consumption of healthy food and neophobia level, comparisons between different categories were performed using goodness of fit tests. For general behavior and tests of independence in the case of behavior by sex and age, we used the Chi square (χ2) procedure, using the statistics package WinSTAT add-in for Microsoft® Excel. A quantitative descriptive analysis, ANOVA was performed for each of the descriptors, using sample and judge factors and their interaction. An analysis of averages for each of the descriptors was performed using Duncan’s test (P < 0.05). A multivariate analysis was also performed with the data obtained in the quantitative descriptive analysis, using principal component analysis and product analysis. Data analysis was performed using the XLSTAT® statistics package.

Results and discussion

Consumption of healthy foods

According to the consumer profiles there was a significant (P < 0.05) difference with a 68.3% interest in the consumption of healthy food (Table 1). Despite the predominance of females on the panel, a significant (P < 0.05) difference was obtained between men and women preferences on healthier foods. According to an analysis of the distribution of population by Chi square values, a difference between the levels of interest was observed for all the tested groups. Women presented a higher interest for healthier food as compared to men (69.5% for women against 63.5% for men). This is, that women were more interested than men with respect to healthier food consumption. Gender has a great influence on the acceptability of healthier foods, moreover when the food contains elements for good health, going beyond mere novelty (Young et al. 2009). In general, women were more likely than men to report avoid high fat content foods, preferring to consume more fiber and fruits and lesser salt (Wardle et al. 2004), besides that adverse impact of high awareness to functional foods decreases with increasing consumer age (Verbeke 2005). In this view, the tendency to consume healthier foods, like cooked sausages containing fiber, is promising according to this study.

Table 1.

Profile of consumers according to gender and age to the consumption of novel foods

| Type of consumers | χ2 | P | Low interest (%) | High interest (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General consumers | 39.73 | 0.000 | 31.7 | 68.3 |

| Gender | ||||

| Men | 4.58 | 0.032 | 36.5 | 63.5 |

| Women | 35.86 | 0.000 | 30.5 | 69.5 |

| Age | ||||

| 30–40 years old | 15.69 | 0.000 | 35.2 | 64.8 |

| 40–50 years old | 21.87 | 0.000 | 26.7 | 73.3 |

The age of consumers was reflected in a high interest in the consumption of healthy foods, with a very high participation of younger people (30–40 years old), increasing to 73.3% in ages between 40 and 50 years.

Food neophobia

The results obtained for healthy foods reflected the degree of neophobia in making a decision between both fibers. Information provided to respondents during the poll increased the acceptance for cooked sausages containing pineapple fiber as compared to same product with cactus pear peel fiber (Table 2). Although food neophobia was influenced by factors such as age, socioeconomic status, marital status and gender, acceptance of functional foods depends on socio-demographic, cognitive and attitudinal factors, simultaneously if the food tastes better or worse than its conventional counterpart (Pliner et al. 1993; Pelchat and Pliner 1995; Martins et al. 1997). When nutritional information was provided for a new product the response from consumers leaned towards acceptance (Villegas et al. 2008).

Table 2.

Chi square for the level of neophobia by fiber source

| Fiber type | χ2 | P | Neophilic (%) | Neophobic (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pineapple peel fiber | 80.880 | 0.000 | 83.4 | 16.6 |

| Cactus pear peel fiber | 0.005 | 0.940 | 50.0 | 50.0 |

R-index

According to the critical values (Bi and O’Mahony 1995), samples with cactus pear fiber presented a significant effect (90.29 and 71.24%, respectively) in both firmness and flavor tests (Table 3). In meat products, R-index values greater than 50% indicate a higher hedonic rating (Pasin et al. 1989). Added pineapple fiber had no effect on sausage firmness (R-index = 50%), whereas the higher R-index value close to 100% (90.29%) indicated that samples formulated with cactus pear fiber were clearly preferred by judges (Lee and Van Hout 2009). For taste, R-index values were slightly higher for pineapple fiber samples than for cactus pear fiber (83.75 and 71.24%, respectively), with a slight preference for sausages containing pineapple fiber. Although the consumers reported a higher neophobia for cooked sausages containing cactus pear fiber, these samples were preferred by the panel. The use of fiber from agro-industrial co-products modified R-index values affecting flavor due the added functional ingredient, but with a positive impact on sausage firmness (Chaparro-Hernández et al. 2013).

Table 3.

R-index by different samples (n = 30, α = 0.05)

| Attribute | IR calculated (%) | IR tabulate + 50%* |

|---|---|---|

| Pineapple fiber | ||

| Firmness | 50.00 | 61.92 |

| Taste | 83.75** | 61.92 |

| Cactus pear fiber | ||

| Firmness | 90.29** | 61.92 |

| Taste | 71.24** | 61.92 |

* Critical values (Bi y O’Mahony 1995)

** Significant (P < 0.05)

Quantitative descriptive analysis

Sample factor analysis showed that judges were highly discriminative (P < 0.05) in appearance: bright/dark; odors: chicken soup and cooked pork; taste: sweet, spicy, pork meat and fibrous; and texture: plasticity and hardness. The factor judge revealed significant (P < 0.05) differences in the use of the scale to assess the attributes of bright/dark, shiny and compact appearance, and in all odor, flavor and texture attributes, meaning that the judges ranked the samples differently on the scale used to perceive different sausage attributes (Sinesio et al. 1990; Sulmont et al. 1997). The use of extenders like legume flours had no effect on color rating (Babatunde et al. 2013). The sample×judge interaction showed no significant (P > 0.05) difference in texture parameters. But a significant (P < 0.05) difference was found in chicken soup, cooked pork, and salty, sweet, cooked and astringent attributes, which indicates consistency in the use of the scale for the product assessment, finding no significant differences (P > 0.05) for most attributes (Pagés et al. 2007).

For odor attributes the different treatments were only significant (P < 0.05) for pork meat, with lower intensity for samples with pineapple fiber. In the evaluation of taste attributes, control formulation showed significantly (P < 0.05) higher levels of intensity in pork meat flavor in cactus pear fiber samples, and the remaining attributes were not significantly (P > 0.05) different. The cooked pork flavor attribute was evaluated as more intense in relation to the rest of the attributes, and similar flavor intensity of fiber was detected for all three formulations. For appearance attributes (Fig. 1a), only the color (light/dark) was significantly (P < 0.05) different, where judges evaluated pineapple fiber sausages as the darkest, followed by the cactus pear fiber sausages and control. Added fiber doesn’t seem to affect other attributes related to sausages appreciation. In odor attributes (Fig. 1b), the different treatments only had significantly (P < 0.05) effect on pork meat odor, being more intense in control samples, followed by the cactus fiber samples. Attributes with lower intensity were smoky, rancid and fermented. In taste attributes (Fig. 1c) sweet was the most intense attribute, with no significantly (P > 0.05) difference among the rest of the attributes. The added fruit fiber was not reflected in the intensity of bitter and fibrous attributes, but the astringent attribute was not significantly (Fig. 1c) detected. Finally, in texture attributes (Fig. 1d), significantly (P < 0.05) differences were observed in hardness and plasticity with cactus pear fruit peel flour and pineapple flour but not significantly (P > 0.05) differences were perceived in intensity of hardness and plasticity (P < 0.05) with the control formulations. Although no significantly (P > 0.05) difference was observed in the moisture attribute, this was also one of the attributes with highest intensity, which could be due to water retention by the fruit peel flour. Likewise, the fibrous texture was detected with a low intensity when added to the formulation of sausages, with similar behavior in flavor (Fig. 1d) fiber.

Fig. 1.

Evaluation of different attributes of sausage formulations: a appearance, b odor, c taste and d texture

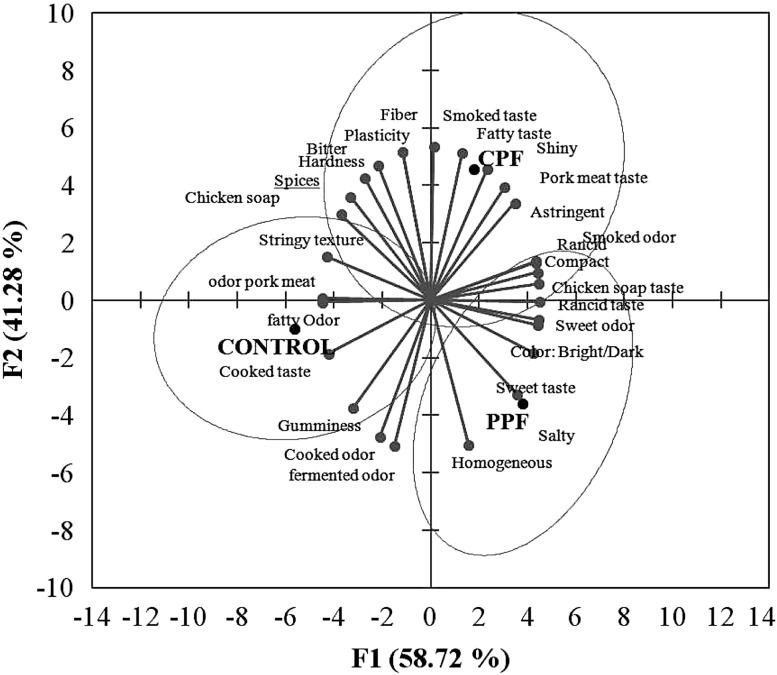

Principal components analysis

In the principal component analysis (Fig. 2), two factors presented a higher explanation of the relationship of analyzed data (41.28 and 58.72%). The incorporation of cactus pear fiber was positively correlated with a shiny appearance, pork meat, smoked and fatty taste. For samples with pineapple fiber, the descriptors negatively correlated were sweet taste and odor, color and salty, besides the homogeneous appearance. Interestingly, both samples with added fiber were positively correlated (positive cluster in both factors) on a compact appearance, rancidity and chicken soup taste. Since the length of the vector indicates the importance of the attributes assigned by the judges (Waichungo et al. 1998), the most negative attributes were cooked and fermented odor. In added fiber samples, fatty taste seems to be the most important one. Employing PCA as well, Szczepaniak et al. (2005) reported that the variability in sensory attributes was connected primarily with the type of dietary fiber, where the higher degree of sensory profiles turned out to be taste (fatty) and aroma. In this research, also the main attributes were related to taste and aroma. The incorporation of fiber enhanced texture and taste of the cooked sausages, since in Control samples the cooked taste and gumminess were negatively correlated along both factors.

Fig. 2.

Biplot of principal component analysis for descriptors in product characterization (PPF pineapple fiber, CPF cactus pear fiber)

Conclusion

The study of acceptance for healthy foods and food neophobia showed that there is potential for the consumption of cooked sausages as formulated with functional ingredients, regardless of the type of dietary fiber (cactus pear fiber or pineapple fiber). The different methodologies used in sensory analysis enable us to identify the sectors where functional meat products with added dietary fiber were acceptable, mainly middle-age women. Although the apparent neophobia to cooked sausage with fiber, in the sensory evaluation sausages with added fiber were evaluated acceptably. Cactus pear fiber samples presented higher R-index score for texture, whereas for taste the R-index for pineapple fiber samples were higher. QDA determined that the attributes of greatest significance were color, sweet, astringent and bitter flavors, pork meat smell and a firm and plastic texture. There was a relationship between the appearance, odor, taste and texture attributes evaluated, according to PCA, demonstrating the importance of sensory attributes on the acceptance and neophobia for added-fiber cooked sausages, as food with functional ingredients.

References

- Babatunde OA, Adetunji VA, Olusola OO. Quality of breakfast sausage containing legume flours as binders. J Biol Life Sci. 2013;4:310–319. doi: 10.5296/jbls.v4i2.3701. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bi J, O’Mahony M. Table for testing the significance of the R-index. J Sensory Stud. 1995;10:431–437. [Google Scholar]

- Cáprita A, Cáprita R, Gianet-Simulescu VO, Raluca-Madalina D. Dietary fiber: chemical and functional properties. J Agroaliment Proc Technol. 2010;16:406–416. [Google Scholar]

- Chaparro-Hernández J, Castillejos-Gómez BI, Carmona-Escutia RP, Escalona-Buendía HB, Pérez-Chabela ML. Evaluación sensorial de salchichas con harina de cáscara de naranja y/o penca de maguey. Nacameh. 2013;7(23):40. [Google Scholar]

- Chávez-Zepeda LP, Cruz-Méndez G, Gracia de Caza L, Díaz-Vela J, Pérez-Chabela ML. Utilización de subproductos agroindustriales como fuente de fibra para productos cárnicos. Nacameh. 2009;3:71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Vela J, Totosaus A, Cruz-Guerrero AE, Pérez-Chabela ML. In vitro evaluation of the fermentation of added-value agroindustrial by-products: cactus pear (Opuntia ficus-indica L.) peel and pineapple (Ananas comosus) peel as functional ingredients. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2013;48:1460–1467. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.12113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Vela J, Totosaus A, Pérez-Chabela ML. Integration of agroindustrial co-products as functional food ingredients: cactus pear (Opuntia ficus indica) flour and pineapple (Ananas comosus) peel flour as fiber source in cooked sausages inoculated with lactic acid bacteria. J Food Process Preserv. 2015;39:2630–2638. doi: 10.1111/jfpp.12513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- García ML, Dominguez R, Gálvez MD, Casas C, Selgas MD. Utilization of cereal of fruit fibres in low fat dry fermented sausages. Meat Sci. 2002;60:227–236. doi: 10.1016/S0309-1740(01)00125-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigor JM, Brennan CS, Hutchings SC, Rowlands DS. The sensory acceptance of fibre-enriched cereal foods: a meta-analysis. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2016;51:3–13. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.13005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HS, van Hout D. Quantification of sensory and food quality: the R-index analysis. J Food Sci. 2009;74:57–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2009.01204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins Y, Pelchat ML, Pliner P. Try it; it´s good and it´s good for you: effects of taste and nutrition information on willingness to try novel foods. Appetite. 1997;28:89–102. doi: 10.1006/appe.1996.0064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O´Mahony M. Adapting short cut signal detection measure to the problem of multiple differential: R index. In: Williams AA, Atkin RK, editors. Sensorial qualities of foods and beverages. Berlin: VCH Publishing; 1983. pp. 69–81. [Google Scholar]

- O’Mahony M. Short-cut signal detection measures for sensory analysis. J Food Sci. 1979;44:302–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1979.tb10071.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Mahony M. Understanding discrimination tests: a user-friendly treatment of response bias, rating and ranking R-index tests and their relationship to signal detection. J Sens Stud. 1992;7:1–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-459X.1992.tb00519.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pagés JC, Bertrand C, Ali R, Husson F, Lé S. Sensory analysis comparison of eight biscuit by French and Pakistani panels. J Sens Stud. 2007;22:665–686. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-459X.2007.00130.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pasin G, O’Mahony M, York G, Weitzel B, Gabriel L, Zeidler G. Replacement of sodium chloride by modified potassium chloride (cocrystalized disodium-5’4nosinate and disodium-5’-guanylate with potassium chloride) in fresh pork sausages: acceptability testing using signal detection measures. J Food Sci. 1989;54:553–555. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1989.tb04648.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pelchat ML, Pliner P. Try it. You´ll like it. Effects of information on willingness to try novel foods. Appetite. 1995;24:153–165. doi: 10.1016/S0195-6663(95)99373-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliner P. Development of measures of food neophobia in children. Appetite. 1994;23:147–163. doi: 10.1006/appe.1994.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliner P, Pelchat M, Grabski M. Reduction of neophobia in humans by exposure to novel foods. Appetite. 1993;20:111–123. doi: 10.1006/appe.1993.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roininen K, Lähteenmäki L, Tuorila H. Quantification of consumer attitudes to health and hedonic characteristics of foods. Appetite. 1999;33:71–88. doi: 10.1006/appe.1999.0232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roininen K, Tuorila H, Zandstra EH, de Graaf C, Vehkalahti K, Stubenitsky K, Mela DJ. Differences in health and taste attitudes and reported behaviour among Finnish, Dutch and British consumers: a cross-national validation of the Health and Taste Attitude Scales (HTAS) Appetite. 2001;37:33–45. doi: 10.1006/appe.2001.0414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnettler B, Crisóstomo G, Sepúlveda J, Mora M, Lobos G, Miranda H, Grunert KG. Food neophobia, nanotechnology and satisfaction with life. Appetite. 2013;69:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinesio F, Risvik E, Rodbotten M. Evaluation of panelist performance in descriptive profiling of rancid sausage. A multivariate study. J Sens Stud. 1990;5:32–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-459X.1990.tb00480.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stone H, Sidel J. Sensory evaluation practices. 2. New York: Academic Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Stone H, Sidel J. Sensory evaluation practices. 3. New York: Academic Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sulmont C, Lesschaeve I, Sauvegeot F, Issanchou S. Comparative training procedures to learn odor descriptors: effects on profiling performance. J Sens Stud. 1997;14:467–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-459X.1999.tb00128.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Szczepaniak B, Piotrowska E, Dolata W, Zawirska-Wojtasiak R. Effect of partial fat substitution with dietary fiber on sensory properties of finely comminuted sausages part I. Wheat and oat fiber. Pol J Food Nutr Sci. 2005;14:309–314. [Google Scholar]

- Toldrá F, Reig M. Sausages. In: Hui YH, editor. Handbook of food products manufacturing. New York: Wiley Interscience; 2007. pp. 252–264. [Google Scholar]

- Verbeke W. Consumer acceptance of functional foods: socio-demographic, cognitive and attitudinal determinants. Food Qual Pref. 2005;16:45–57. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2004.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Villegas B, Carbonell I, Costell E. Effect of product information and consumer attitudes on responses to milk and soybean vanilla beverages. J Sci Food Agric. 2008;88:2426–2434. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.3347. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waichungo WW, Heymann H, Heldman DR. Using descriptive analysis to characterize the effects of moisture sorption on the texture of low moisture foods. J Sens Stud. 1998;15:35–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-459X.2000.tb00408.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle J, Haase AM, Steptoe A, Nillapun M, Jonwutiwes K, Bellisle F. Gender differences in food choice: the contribution of health beliefs and dieting. Ann Behav Med. 2004;27:107–116. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2702_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss J, Gibis M, Schuh V, Salminen H. Advances in ingredient and processing systems for meat and meat products. Meat Sci. 2010;86:196–213. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young ME, Mizzau M, Mai NT, Sirisegaram A, Wilson M. Food for thought. What you eat depends on your sex and eating companions. Appetite. 2009;53:268–271. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]