Abstract

Endometrial polyps are frequently seen in subfertile women, and there is some evidence suggesting a detrimental effect on fertility. How polyps contribute to subfertility and pregnancy loss is uncertain and possible mechanisms are poorly understood. It may be related to mechanical interference with sperm transport, embryo implantation or through intrauterine inflammation or altered production of endometrial receptivity factors. Different diagnostic modalities such as two- or three-dimensional transvaginal ultrasound, saline infusion sonography or hysteroscopy are commonly used to evaluate endometrial polyps with good detection rates. The approach of clinicians towards polyps detected during infertility investigations is not clearly known, and it is quite likely that there is wide variation amongst different groups. Most clinicians suggest hysteroscopy and polyp removal if a polyp is suspected before stimulation for in vitro fertilisation or a frozen embryo transfer cycle. However, the clinical evidence and benefit of different management options during assisted reproduction technology cycles are conflicting. Currently, there is insufficient evidence to recommend one particular option over others when a polyp is suspected during stimulation for in vitro fertilisation. A properly designed randomized controlled trial is needed to determine the best treatment option. In this article, we present the available evidence and our practice related to different diagnostic modalities and management options. We also discuss the available literature relevant to the management of endometrial polyps in relation to natural conception, intrauterine insemination and in vitro fertilisation.

Keywords: Endometrial polyps, Infertility, Ultrasound, Hysteroscopy, In vitro fertilisation

Endometrial polyps are focal growths of the uterine mucosa and consist of endometrial glands, stroma and blood vessels. It is estimated that uterine polyps are found in 10 % of general female population [1]. Whilst they may be asymptomatic, polyps are commonly identified during investigations for abnormal uterine bleeding and infertility. Abnormal uterine bleeding is the most common symptom of endometrial polyps, and in women with such bleeding, the prevalence of endometrial polyps is thought to be between 20 and 30 % [2–4].

In subfertility patients, the diagnosis of endometrial polyps is frequently an incidental finding. The association between endometrial polyps and subfertility is controversial, as many women with polyps have successful pregnancies. However, recently there has been an accumulation of publications in the literature, suggesting that the polyps are indeed relevant to fertility and fertility treatment outcome. In this article, we give an overview of epidemiology, diagnosis and management of polyps in subfertile population and discuss possible mechanisms how polyps may affect fertility.

Prevalence of Endometrial Polyps in Infertile Women

Since transvaginal ultrasound examination (TVUS) has become a standard part of the gynaecological assessment, and saline infusion sonography or hysteroscopy are often performed if intrauterine mass lesions are suspected, polyps are more frequently detected. This approach has led to an increase in the diagnosis of endometrial polyps in subfertile and otherwise asymptomatic patients.

Polyps are considered amongst factors that might contribute to infertility and recurrent pregnancy loss. It has been postulated that congenital uterine anomalies and acquired structural cavitary defects such as leiomyomas, polyps and synechiae might have negative impact on endometrial receptivity and thus implantation failure. This presents a major clinical challenge and is a cause of considerable stress to patients.

The prevalence of such unsuspected intrauterine abnormalities, diagnosed by hysteroscopy prior to in vitro fertilisation (IVF), has been described to be between 11 and 45 % [5–7]. Endometrial polyps are the most commonly reported uterine structural abnormalities. Whilst one study [5] identified polyps in 32 % of patients (323/1000) undergoing IVF, another [6] showed 41 (6 %) patients with polyps in a similar patient population of 678 asymptomatic IVF patients. Endometrial polyps also appear to be the most commonly detected abnormality (16.7 %) in patients with recurrent implantation failures after IVF [6]. It is suggested that polyps have higher incidence in women with endometriosis (46.7 %), although this high figure has not been reported by other groups [8].

Possible Mechanisms of Polyp–Subfertility Association

How polyps contribute to subfertility and pregnancy loss is uncertain and the mechanism is poorly understood. It may be related to mechanical interference with sperm transport, embryo implantation or through intrauterine inflammation or increased production of inhibitory factors such as glycodelin.

In a retrospective study involving 230 subfertile women undergoing hysteroscopy and polypectomy, Yanaihara et al. concluded that the location of the endometrial polyp may influence spontaneous pregnancy rates and fertility outcome. The pregnancy rate within 6 months after surgery was 57.4 % for polyps located at the uterotubal junction, 40.3 % for multiple polyps, 28.5 % for posterior wall polyps, 18.8 % for lateral wall polyps and 14.8 % for anterior uterine wall polyps [9]. These results suggest that the mass of polyps may interfere with the reproductive processes such as sperm transport, embryo implantation or early pregnancy development. Conversely, in another retrospective study 83 subfertile women with a history of menstrual disorder, hysteroscopic polypectomy appeared to improve fertility and pregnancy rates irrespective of the size or number of the polyps. In particular, there was no difference in pregnancy or miscarriage rates between women who had polypectomy for a small (≤1 cm) and those who had surgery for a bigger or multiple polyps [10]. Lack of association between the size of polyps and fertility outcomes goes against a mechanical effect, as a bigger effect would be expected in the presence of larger polyps.

Glycodelin, a glycoprotein, has been shown to inhibit sperm-oocyte binding and NK cell activity. In ovulatory human endometrium, glycodelin levels are very low between 6 days before and 5 days after ovulation (peri-ovulatory period). Low glycodelin levels may facilitate fertilisation, and then, the levels increase significantly 6 days after ovulation to suppress NK cell activity and render the endometrium receptive to implantation. It is speculated that fertilisation and endometrial receptivity may be altered by increased glycodelin production in the uterine cavity of patients with leiomyomas and polyps at the time (peri-ovulatory) when uterine glycodelin levels should be absent or low [11].

It is also suggested that the presence of polyps may alter HOXA10 and HOXA11 gene expression, established molecular markers of endometrial receptivity, and thus impair endometrial receptivity in uteri with polyps [12].

Diagnosis

The diagnostic modalities that are commonly used to evaluate endometrial polyps include a two- or three-dimensional transvaginal ultrasound, best performed in the early proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle, saline infusion sonography and hysteroscopy. The diagnostic accuracy of 2D TVUS is relatively poor compared with other diagnostic modalities such as saline infusion sonography (SIS) or hysteroscopy. An endometrial polyp is suspected by the presence of a hyperechogenic endometrial mass (Fig. 1).

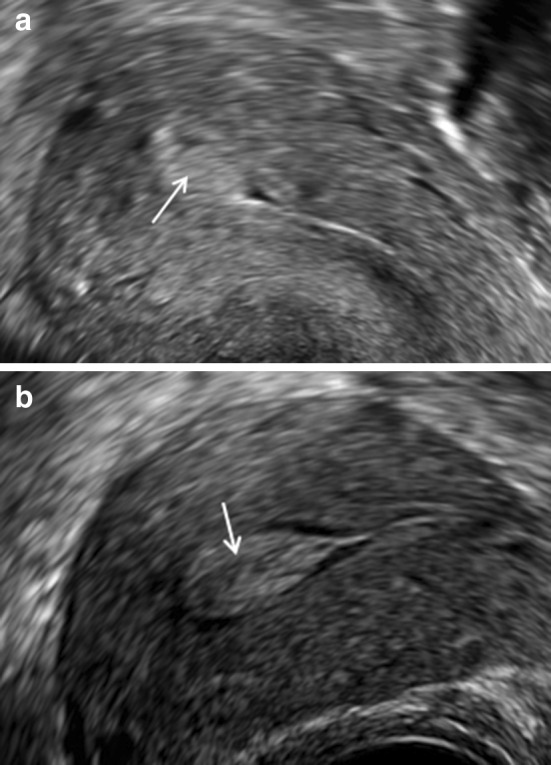

Fig. 1.

a Transvaginal ultrasound scan 2D image showing a fundal polyp (arrow), b a polyp filling the cavity (arrow)

Performing the ultrasound examination in early proliferative phase, when the endometrium is thin, makes it easier to see the polyp. Sessile polyps can be confused by submucous fibroids. It might also be difficult to distinguish between a true polyp and polypoid endometrium by ultrasound, especially after superovulation, which tends to cause a thick proliferative endometrium.

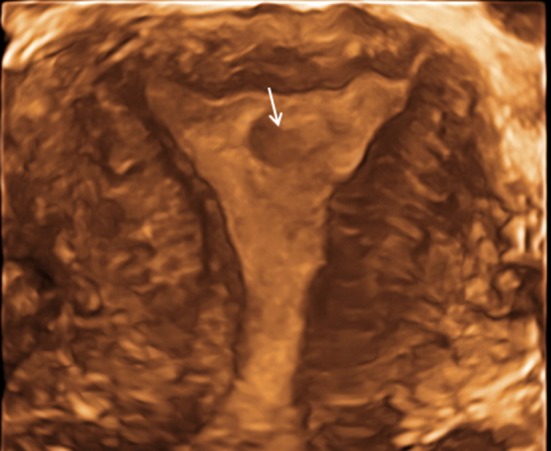

In one study, hysteroscopy confirmed the ultrasound findings in 90 % of cases [13]. Fatemi et al. [6] identified polyps hysteroscopically in 41 out of 678 unselected, asymptomatic, infertile women with a normal transvaginal scan. In our practice, we perform 3D imaging (Fig. 2) of the uterus as a routine during baseline ultrasound scans with the aim of improving diagnostic accuracy [14].

Fig. 2.

Three-dimensional US appearance of an endometrial polyp (arrow)

A systematic review and meta-analysis suggested that saline infusion sonography has a high degree of diagnostic accuracy in the detection of all types of intrauterine abnormalities with a sensitivity and specificity of 88 and 94 %, respectively. The diagnostic accuracy of SIS remained high when analysed separately for individual pathologies such as endometrial polyps, submucous myomas, intrauterine adhesions and congenital uterine anomalies. It is also suggested that SIS can be considered as an alternative to hysteroscopy as the specificity reaches close to 100 % in detecting intrauterine adhesions, uterine anomalies, endometrial polyps and submucous myomas [15].

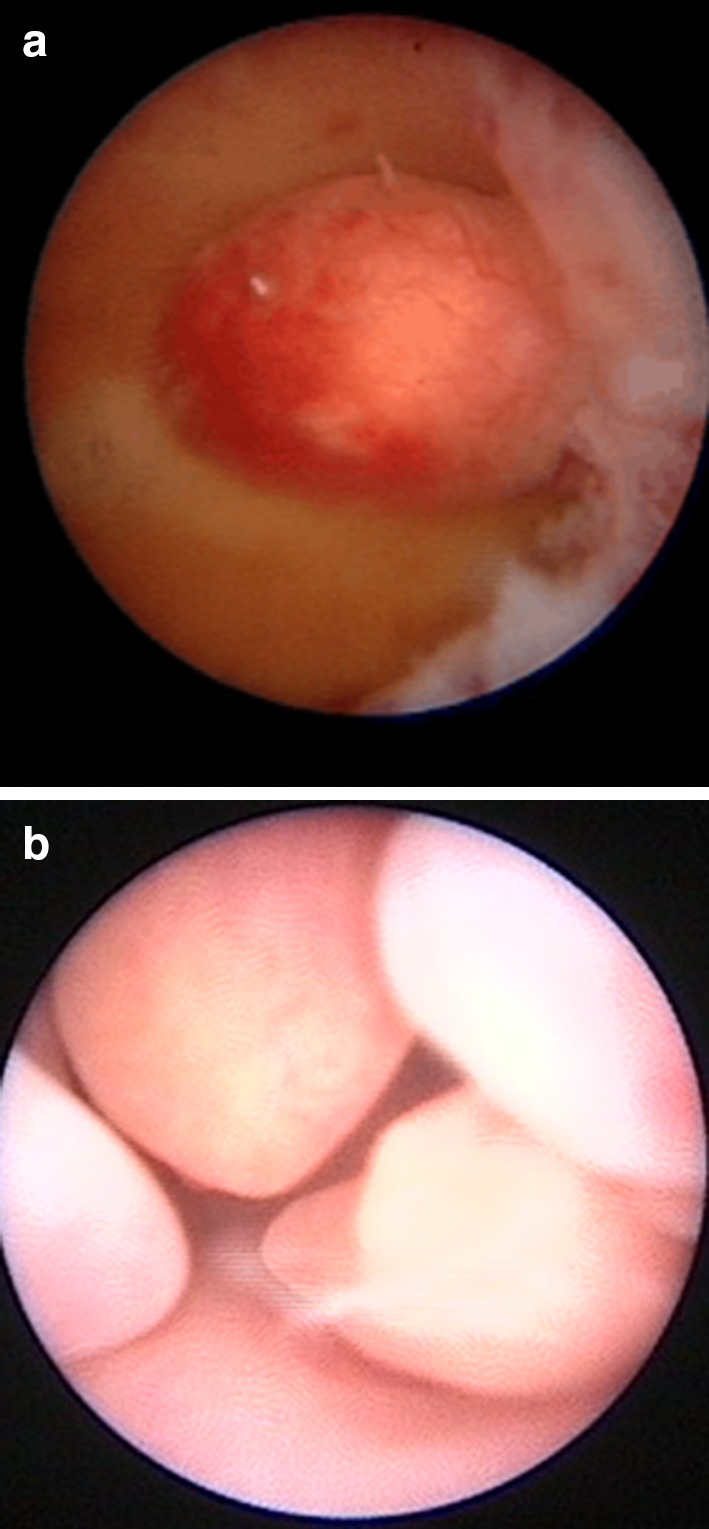

Hysteroscopy remains the gold standard in the diagnosis of endometrial polyps (Fig. 3). Besides, hysteroscopy allows simultaneous treatment in the form of removal of the endometrial lesions such as polyps and small submucous fibroids.

Fig. 3.

a Hysteroscopy image showing a left lateral wall polyp, b multiple polyps within the uterine cavity

In our practice, we carry out a 2D and 3D TVUS as a baseline investigation. If TVUS is suggestive of endometrial polyps, we perform a hysteroscopy, usually as an outpatient procedure, depending on the patient’s preference. If the TVUS is inconclusive in an infertile and otherwise asymptomatic woman, we perform 3D saline infusion sonography (3D SIS).

Management

The approach of clinicians towards polyps detected during infertility investigations is not clearly known, and it is quite likely that there is wide variation amongst different groups. The majority of published data recommend removal of polyps, but this may be due to publication bias, as groups who do not routinely look for polyps may be less likely to publish data on impact of polyps or polyp removal. Some endometrial polyps may resolve spontaneously, as regression has been observed in 27 % of cases [16].

Endometrial polyps are usually removed as part of a hysteroscopic procedure; removal may be either a blind procedure using a curette or polyp forceps after hysteroscopic diagnosis, or may be under direct vision using operative minihysteroscopes or resectoscopes. Published surveys suggest differences of practice in different countries. In the Netherlands, the majority of clinicians appear to remove polyps under direct vision either in the outpatients or under general anaesthesia [17, 18]. In contrast, the preference of clinicians in the UK was blind avulsion or curettage after hysteroscopic location [19]. These surveys also indicated that the clinicians were more likely to perform these procedures in the outpatient setting at university teaching hospitals, whereas general anaesthetic procedures were more likely in general hospitals.

Historically, it is believed that 10 % of intrauterine lesions, mainly polyps, are missed during ‘blind’ curettage [20]. For this reason, hysteroscopy-directed polypectomy using scissors, a loop electrode, electric probe or a morcellator is recommended to minimize damage to the surrounding endometrium and to ensure the polyp has been removed in its entirety. The resectoscope appears to be the method of choice and with least recurrence rate compared to electric probe, microscissors and grasping forceps [21].

Our practice is to carry out the majority of polyp removals in the outpatients as ‘see and treat’ procedures under direct vision using bipolar electrodes and/or mechanical biopsy forceps [22]. An economic analysis of this approach suggests that this is more cost-effective to the health service compared to routine general anaesthetic procedures [23].

Outcome

A number of publications indicate that removal of endometrial polyps is beneficial for natural conceptions [24], intrauterine insemination (IUI) [25] and assisted reproduction technologies (ART).

Natural Conception

Three nonrandomized studies found an association between polypectomy and improved spontaneous pregnancy rates. Varasteh et al. [24] studied infertile women with and without endometrial polyps and found a pregnancy rate of 78.3 % after polypectomy compared with 42.1 % in those with normal uterine cavity. Spiewankiewicz et al. [26] reported a pregnancy rate of 76 % where 19 out of 25 infertile patients conceived within 12 months after polypectomy, whereas Shokeir et al. [27] reported a 50 % pregnancy rate after polypectomy in such patients. These studies suggest women with otherwise unexplained infertility may benefit from polypectomy.

Intrauterine Insemination

Perez-Medina et al. randomized 215 infertile women, with ultrasonographically diagnosed endometrial polyps undergoing IUI, to either hysteroscopic polypectomy in the study group or diagnostic hysteroscopy and polyp biopsy in the control group. Patients who underwent hysteroscopic polypectomy had a better possibility of becoming pregnant after polypectomy, with a relative risk of 2.1 (95 % confidence interval 1.5–2.9) [25].

In another study, 120 infertile patients planned to have IUI and diagnosed with endometrial polyps were randomly allocated either to hysteroscopic polypectomy or no intervention. All patients were scheduled to receive four cycles of IUI. The cumulative pregnancy rates were significantly higher in the study group (38.3 vs 18.3 %; p = 0.015), suggesting that hysteroscopic polypectomy prior to IUI is an effective measure and improves pregnancy rates [28].

Endometrial Polyp Management and IVF

When suspected by ultrasound prior to commencement of stimulation for IVF or prior to frozen embryo transfer (FET), polyps are usually further investigated and treated. However, the management of polyps found incidentally during the course of stimulation for IVF is controversial. Treatment options include continuation of ovarian stimulation followed by fresh transfer, freezing all embryos and replacement of frozen–thawed embryos after removal of the polyp, or cancellation of the treatment cycle and removal of the polyp. The factors that affect decision-making include the number of embryos created, previous reproductive history and the success rate of the FET programme, as well as the clinicians’ preference.

Lass et al. examined the effect of polyps on 83 women with ultrasonographically identified polyps <2 cm and divided them in two groups before oocyte retrieval during IVF. Forty-nine women completed the standard IVF and embryo transfer treatment, and 34 women underwent hysteroscopic polypectomy immediately after oocyte retrieval and the embryos were cryopreserved and transferred in a subsequent cycle. No statistically significant difference was observed in pregnancy rates between the two groups and compared with the overall pregnancy rate for their clinic during the same period of time. There was a trend towards increased pregnancy loss in the fresh embryo transfer group [13].

Another study assessed the effect of endometrial polyps <1.5 cm in size on intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) cycles. Patients were divided into three groups: patients with endometrial polyps discovered during ovarian stimulation (n = 15), patients who underwent hysteroscopic polyp resection prior to ICSI cycle (n = 20) and patients without polyps (n = 956). The pregnancy rates were 53.3, 45.0 and 40.1 %, respectively. There was no statistical difference in pregnancy and implantation rates between the three groups [29].

The effect of hysteroscopic polypectomy on IVF outcome without cycle cancellation was assessed in a case series of six patients who underwent hysteroscopic polypectomy on days 7 and 9 with a wire loop without use of electric current during an IVF cycle. A 50 % pregnancy rate was observed, suggesting that hysteroscopic polypectomy may not be detrimental to IVF cycle outcome [30].

Tiras et al. assessed the effect of polyps, <1.5 cm in size, diagnosed before or during ICSI. Group 1 (n = 47) were patients diagnosed with an endometrial polyp and had hysteroscopic polypectomy before stimulation. These were compared with 47 matched control patients without endometrial polyps who underwent standard ICSI cycle (Group 2). Group 1 patients had live birth rates similar to their controls (Group 2) (25.5 vs 31.9 %). This study also examined 128 patients (Group 3) diagnosed with an endometrial polyp during stimulation in their ICSI cycle. Group 3 was compared with 128 match control patients without endometrial polyps who underwent standard ICSI cycle (Group 4). Groups 3 and 4 also had similar live birth rates (40.6 vs 39.8). This retrospective study suggests that patients with an endometrial polyp detected and resected before ICSI cycle had similar pregnancy rates compared with patients with no endometrial polyps. It also proposes that for endometrial polyps diagnosed during stimulation and <1.4 cm in size, it is not necessary to intervene or cancel the embryo transfer [31].

In our practice, we usually perform 3D SIS routinely before IVF cycles with fresh or frozen embryo transfer. This makes it very unlikely to diagnose polyps during stimulation. In general, we recommend hysteroscopic polypectomy for polyps diagnosed before stimulation. If we diagnose a polyp during stimulation we counsel our patients and discuss different options of treatment based on available evidence. We do not usually consider polypectomy during stimulation taking into consideration the potential harmful effect of such a procedure just before embryo transfer. With the current advances in embryo freezing and the frozen embryo transfer cycles outcome, which is higher than fresh embryo transfer in our unit, we tend to freeze all embryos after egg collection and plan for a hysteroscopic polypectomy followed by a frozen embryo transfer cycle.

Conclusion

Endometrial polyps are commonly seen in subfertile women, and there is some evidence suggesting a detrimental effect of polyps on fertility. Use of appropriate and sensitive diagnostic tests for subfertility and prior to fertility treatment is commonly performed with good detection rates. The limited data available on removal of polyps on spontaneous pregnancy and intrauterine insemination success rates suggest a potential benefit. Most clinicians suggest hysteroscopy and polyp removal if a polyp is suspected before stimulation for IVF or a frozen embryo transfer cycle. However, the clinical evidence and benefit of different management options during ART cycles are conflicting. Currently, there is insufficient evidence to recommend one particular option over others when a polyp is suspected during stimulation for IVF. A properly designed randomized controlled trial is needed to determine the best treatment option.

Ali Al Chami

graduated as a medical doctor in 2006. He received obstetrics and gynaecology specialty training between 2006 and 2011 at the American University of Beirut Medical Centre. His current position is clinical research fellow in reproductive medicine and assisted conception at the Reproductive Medicine Unit, University College London Hospital. Ali Al Chami has also conducted research on IVF and infertility. He is especially interested in fertility preservation, pre-implantation genetic diagnosis and reproductive surgery.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

Ertan Saridogan and Ali Al Chami have no conflict of interest.

Statement of human and animal rights

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Footnotes

Dr. Ali Al Chami is a Clinical Research Fellow; Dr. Ertan Saridogan is a Consultant in Reproductive Medicine and Minimal Access Surgery.

References

- 1.Clark TJ, Middleton L, Cooper N, et al. A randomised controlled trial of outpatient versus inpatient polyp treatment (OPT) for abnormal uterine bleeding. Health Technol Assess. 2015;19(61). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Bakour SH, Khan KS, Gupta JK. The risk of premalignant and malignant pathology in endometrial polyps. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;8:182–183. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2002.810220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clevenger-Hoeft M, Syrop CH, Stovall DW, et al. Sonohysterography in premenopausal women with and without abnormal bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:516–520. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00345-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elfayomy AK, Habib FA, Alkabalawy MA. Role of hysteroscopy in the detection of endometrial pathologies in women presenting with postmenopausal bleeding and thickened endometrium. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;285:839–843. doi: 10.1007/s00404-011-2068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hinckley MD, Milki AA. 1000 office-based hysteroscopies prior to in vitro fertilization: feasibility and findings. JSLS. 2004;8:103–107. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fatemi HM, Kasius JC, Timmermans A, et al. Prevalence of unsuspected uterine cavity abnormalities diagnosed by office hysteroscopy prior to in vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:1959–1965. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Makrakis E, Hassiakos D, Stathis D, et al. Hysteroscopy in women with implantation failures after in vitro fertilization: findings and effect on subsequent pregnancy rates. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16:181–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim MR, Kim YA, Jo MY, et al. High frequency of endometrial polyps in endometriosis. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10:46–48. doi: 10.1016/S1074-3804(05)60233-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yanaihara A, Yorimitsu T, Motoyama H, et al. Location of endometrial polyp and pregnancy rate in infertility patients. Fertil Steril. 2008;90(1):180–182. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.05.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stamatellos I, Apostolides A, Stamatopoulos P, et al. Pregnancy rates after hysteroscopic polypectomy depending on the size or number of the polyps. Arch Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;277:395–399. doi: 10.1007/s00404-007-0460-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rrichlin S, Ramachandran S, Shanti A, et al. Glycodelin levels in uterine flushings and in plasma of patients with leiomyomas and polyps: implications and implantation. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:2742–2747. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.10.2742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rackow BW, Jorgensen E, Taylor H. Endometrial polyps affect uterine receptivity. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:2690–2692. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lass A, Williams G, Abusheikha N, et al. The effect of endometrial polyps on outcomes of in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycles. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1999;16:410–415. doi: 10.1023/A:1020513423948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Momtaz M, Marzouk A, Ebrashy A. Three-dimensional ultrasonography in the evaluation of the uterine cavity. Middle East Fertil Soc J. 2007;12(1).

- 15.Seshadri S, El-Toukhy T, Douiri A, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of saline infusion sonography in the evaluation of uterine cavity abnormalities prior to assisted reproductive techniques: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21:262–74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Leing M, Istre O, Sandvik L, et al. Prevalence 1-year regression rate, and clinical significance of asymptomatic endometrial polyps: cross-sectional study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16:465–471. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Timmermans A, Van Dongen H, Mol BW, et al. Hysteroscopy and removal of endometrial polyps: a Dutch survey. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008;138:76–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Dijk L, Breijer MC, Veersema S, et al. Current practice in the removal of benign endometrial polyps: a Dutch survey. Gynecol Surg. 2012;9:163–168. doi: 10.1007/s10397-011-0707-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark TJ, Khan KS, Gupta JK. Current practice for the treatment of benign intrauterine polyps: a national questionnaire survey of consultant gynaecologists in UK. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2002;103:65–67. doi: 10.1016/S0301-2115(02)00011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Word B, Gravlee LC, Wideman GL. The fallacy of simple uterine curettage. Obstet Gynecol. 1958;12:642–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prutthipan S, Herabutya Y. Hysteroscopic polypectomy in 240 premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2005;83:705–709. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gulumser C, Narvekar N, Pathak M, et al.. See-and-treat outpatient hysteroscopy: an analysis of 1109 examinations. Reprod. BioMed. Online 20(3), 423–429. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Saridogan E, Tilden D, Sykes D, et al. Cost-analysis comparison of outpatient see-and-treat hysteroscopy service with other hysteroscopy service models. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17(4):518–525. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Varasteh NN, Neuwirth RS, Levin B, Keltz MD. Pregnancy rates after hysteroscopic polypectomy and myomectomy in infertile women. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:168–171. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00278-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perez-Medina T, Bajo-Arenas J, Salazar F, et al. Endometrial polyps and their implication in the pregnancy rates of patients undergoing intrauterine insemination: a prospective, randomized study. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:1632–1635. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spiewankiewicz B, Stelmachow J, Sawicki W, et al. The effectiveness of hysteroscopic polypectomy in cases of female infertility. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2003;30:23–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shokeir TA, Shalan HM, El-Shafei MM. Significance of endometrial polyps detected hysteroscopically in eumenorrheic infertile women. J Obstet Gynecol Res. 2004;30:84–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2003.00163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shohayeb A, Shaltout A. Persistent endometrial polyps may affect the pregnancy rate in patients undergoing intrauterine insemination. Middle East Fertil Soc J. 2011;16:259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.mefs.2011.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Isikoglu M, Berkkanoglu M, Senturk Z, et al. Endometrial polyps smaller than 1.5 cm do not affect ICSI outcome. Reprod Biomed Online. 2006;12:199–204. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60861-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Batioglu S, Kaymak O. Does hysterocopic polypectomy without cycle cancellation affect IVF? Reprod Biomed Online. 2005;10:767–769. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)61121-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tiras B, Korucuoglu U, Polat M, et al. Management of endometrial polyps diagnosed before or during ICSI cycles. Reprod Biomed Online. 2012;24:123–128. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]