Abstract

SWEET (Sugars Will Eventually be Exported Transporter) proteins, a novel family of sugar transporters, mediate the diffusion of sugars across cell membranes and acts as key players in sucrose phloem loading. Manipulation of SWEET genes in plants leads to various effects on resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses due to disruption of sugar efflux and changes in sugar distribution. In this study, a member of the SWEET gene family, IbSWEET10, was cloned from the sweet potato line ND98. mRNA expression analysis in sweet potato and promoter β-Glucuronidase analysis in Arabidopsis showed that IbSWEET10 is highly expressed in leaves, especially in vascular tissue. Transient expression in tobacco epidermal cells revealed plasma membrane localization of IbSWEET10, and heterologous expression assays in yeast indicated that IbSWEET10 encodes a sucrose transporter. The expression level of IbSWEET10 was significantly up-regulated in sweet potato infected with Fusarium oxysporum Schlecht. f. sp. batatas. Further characterization revealed IbSWEET10-overexpressing sweet potato lines to be more resistant to F. oxysporum, exhibiting better growth after infection compared with the control; conversely, RNA interference (RNAi) lines showed the opposite results. Additionally, the sugar content of IbSWEET10-overexpression sweet potato was significantly reduced, whereas that in RNAi plants was significantly increased compared with the control. Therefore, we suggest that the reduction in sugar content caused by IbSWEET10 overexpression is the major reason for the enhanced F. oxysporum resistance of the transgenic plants. This is the first report that the IbSWEET10 transporter contributes to the resistance of sweet potato to F. oxysporum. The IbSWEET10 gene has the great potential to be used for improving the resistance to F. oxysporum in sweet potato and other plants.

Keywords: IbSWEET10, plasma membrane, sucrose transporter, Fusarium oxysporum, sweet potato

Introduction

Sugars are essential substrates for the fundamental processes of plant growth, the major energy sources for generating adenosine triphosphate (ATP), and the main precursor for various storage carbohydrates (Eveland and Jackson, 2012; Guo et al., 2014). In addition, sugars have important roles in signal transduction in higher plants and can regulate many developmental and physiological processes by influencing expression of different sets of genes in various pathways (Koch, 1996; Gibson, 2000; Rolland et al., 2006). The responses of plants to sugar levels also help to integrate metabolism, growth, development and environmental stress responses (Huang et al., 2014). In plants, carbohydrates are synthesized in source leaves, mainly in the form of sucrose and are translocated to sink tissues to sustain heterotrophic metabolism and growth (Roitsch and Gonzalez, 2004). Indeed, sucrose metabolism, partitioning and sensing are proven to be pivotal for many plant processes such as flowering (Roldán et al., 1999), seed germination (Finkelstein and Lynch, 2000), tuber formation (Mullerrober et al., 1992), nutrient synthesis (Forde, 2002) and responses to biotic stresses (Lemoine et al., 2013).

Long-distance transport of sugar to sink organs occurs via the vascular system, which begins with sucrose loading through the sieve element-companion cell complex (SE/CC) by plant sugar transporters, such as SUTs /SUCs (disaccharide transporters, DSTs) and MSTs (monosaccharide transporters). Functioning as sugar/proton symporters, both DSTs and MSTs belong to the major facilitator superfamily (MFS), the members of which possess 12 transmembrane (TM) helices (Sauer et al., 1990; Marger and Saier, 1993; Sauer and Stolz, 1994; Boorer et al., 1996; Zhou et al., 1997). At least nine DSTs and 53 MSTs are encoded by the Arabidopsis genome, with most being localized to the plasma membrane (Williams et al., 2000; Lalonde et al., 2004; Büttner, 2007). AtSUC2 and -4 are involved in sucrose phloem loading in source leaves; AtSUC2 is mainly expressed in collection and transport phloem and AtSUC4 in minor veins (Weise et al., 2000; Srivastava et al., 2008). Tissue-specific expression of AtSUCs plays key roles in the sugar partitioning of different organs, eventually affecting their development, some examples are AtSUC1 in pollen (Sivitz et al., 2008), AtSUC5 in endosperm (Baud et al., 2005) and AtSUC9 in flowers (Sivitz et al., 2007). In addition to roles in plant development, SUTs respond to abiotic stresses and therefore contribute to the environmental tolerance of plants. The transcript levels of certain genes, such as AgSUT1 in celery (Noiraud et al., 2000) and OsSUT2 in rice (Ibraheem et al., 2011), are significantly altered in response to salt or drought stress. Furthermore, RNA interference (RNAi) of PtaSUT4 in Populus tremula resulted in delayed wilting during acute drought stress (Frost et al., 2012). Although the role of the SUT family in plant abiotic tolerance is generally attributed to their functions in sugar transport and compartmentalization, further investigation of the detailed mechanisms is needed.

The SWEET (Sugars Will Eventually be Exported Transporter) family comprises a newly described family of sugar transporters that are ubiquitous in prokaryotes, plants and animals. As uniporters, SWEET proteins mediate uptake or efflux of various mono- and disaccharides across the plasma membrane or the tonoplast and exhibit low sugar affinity (Chen et al., 2010). Usually, SWEET proteins are classified into three major types based on the number of 3-TM domains, semiSWEET (bacteria) with a single 3-TM domain, SWEET (eucaryotes) with a linker in the middle of two 3-TM domains (7-TM) and extraSWEET (Vv14G09070) with the duplication of 7-TM (Xuan et al., 2013; Patil et al., 2015). In addition, Hu et al. (2016) identified a fusion of archaeal and bacterial SemiSWEETs to form eukaryotic SWEETs in Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. Members of the SWEET family underwent expansion during plant evolution. For example, the genomes of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and Physcomitrella patens harbor 5 and 6 SWEET genes, respectively, whereas 8 are present in Amborella trichopoda, the earliest divergent angiosperm, 47 and 52 are found in the dicotyledon Eucalyptus grandis and soybean (Eom et al., 2015; Patil et al., 2015). The Arabidopsis genome contains 17 members of the SWEET family, which can be grouped into four phylogenetic subclades, and 21 members have been identified in rice (Chen et al., 2010).

Variation among SWEETs in different subclades in Arabidopsis may indicate their sugar transport preferences. Clade I SWEETs mainly transport 2-deoxyglucose, whereas clade II prefers glucose. All members in clade III utilize sucrose as a substrate, and AtSWEET16 and -17 in clade IV act as fructose uniporters (Chen L.Q. et al., 2015). The functions of AtSWEETs have been studied extensively. AtSWEET1, -5, -8, and -9 are involved in the development of reproductive organs such as pollen (tube) and nectar (Engel et al., 2005; Guan et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2010; Lin et al., 2014). AtSWEET4, -11, -12, -16, and -17, have essential roles in the growth of aerial parts or roots as well as abiotic resistance by influencing sugar partitioning (Chen et al., 2012; Klemens et al., 2013; Guo et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2016). Overexpression of OsSWEET5 led to growth retardation and precocious senescence of seedlings by regulating auxin signaling pathway in rice (Zhou et al., 2014). ZmSWEET4c and OsSWEET4 are key players for hexose transport across the basal endosperm transfer layer during seed filling in maize and rice, respectively (Sosso et al., 2015). Kanno et al. (2016) found that AtSWEET13 and AtSWEET14 mediated cellular gibberellin (GA) uptake, suggesting they might modulate GA responses in Arabidopsis. The PsSWEET genes were actively expressed during seed development and germination in pea (Jameson et al., 2016). The interactions of SWEET and CWINV genes and cytokinins led to the loss of apical dominance and the appearance of multiple shoots after infection by Rhodococcus fascians in pea (Dhandapani et al., 2016). OsSWEET11 (Os8N3) and OsSWEET14 (Os11N3) which were characterized to be the susceptibility (S) genes mediated the resistance to Xanthomonas oryzae pv. Oryzae in rice (Yang et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2011; Yuan and Wang, 2013). AtSWEET2 encodes a vacuolar glucose transporter that prevents sugar loss from roots and thus contributes to resistance to Pythium irregulare (Chen H.Y. et al., 2015). These findings indicate that the SWEET genes have multiple functions and play important roles in the processes of plant growth and development and resistance to biotic/abiotic stresses.

Sweet potato [Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.] is the seventh most important staple crop (Zhai et al., 2016) and one of the most important root crops in the world, grown on at least 8 million hectares in 114 countries worldwide (Khoury et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2016); however, its yield is severely limited by pathogens (Feng et al., 2011). As biotic pathogens obtain nutrients from their hosts for growth and reproduction and cause diseases, the nutritional relationship between pathogens and hosts is an important aspect of infection (Hancock and Huisman, 1981). Fusarium, a soil-borne fungus, which infects plant roots through wounds (Keane, 2012), typically acquires nutrients from the host for spore germination, and carbon is a major nutrient in this process (Baker, 1968). One species, Fusarium oxysporum Schlecht. f. sp. batatas causes fusarium wilt or stem rot of sweet potato, a major disease that limits the production of this crop (Clark et al., 1998). It has become one of the most serious diseases threatening sweet potato production in southern China. This pathogen can persist in soil for many years, invading plants through the seedling base, wounded roots or seeds, resulting in wilt disease or even death (Clark, 1994). Developing disease-resistant varieties is an important objective of sweet potato breeding. However, little work has been performed on the cloning of F. oxysporum resistance-associated genes in sweet potato and the mechanism of disease resistance is not clear. In sweet potato, the SWEET genes have not been reported and their functions remain to be elucidated.

In this study, we cloned a member of the SWEET family from sweet potato, IbSWEET10, a gene that encodes a sugar transporter protein involved in sucrose transport. β-Glucuronidase (GUS) analysis revealed its leaf-dominant expression, particularly in vascular tissue in Arabidopsis. IbSWEET10-GFP analysis indicated plasma membrane localization of the IbSWEET10 protein in tobacco and yeast, respectively. Moreover, we developed IbSWEET10-overexpressing and RNA-interference sweet potato lines and analyzed its contribution to the resistance to F. oxysporum in sweet potato. The findings will contribute to the improvement of disease resistance in sweet potato through molecular breeding.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials

Sweet potato line ND98 and cv. Lizixiang were cultivated in a greenhouse under a regime of 16 h light and 8 h darkness (28°C). ND98 is resistant to F. oxysporum and Lizixiang is susceptible to this disease. ND98 was used for gene cloning in this study. One expressed sequence tag (EST) selected from the ND98 EST library constructed at our laboratory was up-regulated after the infection of F. oxysporum in ND98 and was used for gene cloning. The cloned gene was further introduced into Lizixiang for function characterization. Arabidopsis thaliana plants (Col-0) were grown in a 16-h light/8-h dark climate-controlled chamber at 22°C for analyzing the promoter of this gene.

Cloning and Sequence Analysis of IbSWEET10 and the 5′-Promoter Region

Total RNA was extracted from the fresh leaves of 4-week-old in vitro-grown plants of ND98 using RNAprep Pure Plant Kit (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China). The RNA samples were reverse-transcribed according to the instructions of PrimeScriptTM II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (TaKaRa, Beijing, China). Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends (RACE) was then applied to amplify the full-length sequence of IbSWEET10 using SMARTer RACE 5′/3′ Kit (TaKaRa, Beijing, China). Gene-specific primers (GSPs) were used for 5′ RACE (5GSP1 and -2) and 3′ RACE (3GSP1 and -2). Amplification of the genomic sequence of IbSWEET10 with GS-F/R primers was performed using genomic DNA extracted from the fresh leaves of 4-week-old in vitro-grown ND98 plants, and the 5′-promoter region of IbSWEET10 was isolated using the GSPs (GW1 and -2) and Genome Walking Kit (TaKaRa, Beijing, China). All polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products were subcloned into the pMD19-T vector (TaKaRa, Beijing, China) and then transformed into competent Escherichia coli strain DH5α cells and sequenced. The primers used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

The open reading frame (ORF) of IbSWEET10 was predicted using ORF Finder1. The molecular weight and isoelectric point (pI) of the IbSWEET10 protein were calculated at http://web.expasy.org/compute_pi/. Multiple sequence alignment of the IbSWEET10 protein with other SWEET10 proteins was performed using DNAMAN software. MEGA 6.0 software was used to construct the phylogenetic tree with the neighbour-joining (NJ) method.

Expression Analysis of IbSWEET10 in Sweet Potato and Arabidopsis

Total RNA was isolated from roots, stems, leaves and petioles of 4-week-old in vitro-grown ND98 plants and storage roots, fibrous roots, stems, leaves and petioles of 3-month-old ND98 plants in the field. Total RNA was extracted as described above, and first-strand cDNA was synthesized using the PrimeScriptTM RT Reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Perfect Real Time; TaKaRa, Beijing, China). Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed to determine the transcript levels of IbSWEET10 using SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Tli RNaseH Plus; TaKaRa, Beijing, China) and the 7500 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The primers used to amplify IbSWEET10 and IbActin (internal control, AY905538) are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

To generate the PIbsweet10-GUS construct, the IbSWEET10 promoter fragment containing the 5′ untranslated region (5′UTR) was amplified from the ND98 genomic DNA and subcloned into the expression vector pMDC162 at PacI and AscI sites. The reconstructed plasmid was introduced into the GV3101 strain of A. tumefaciens. Arabidopsis plants were transformed using the floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998), and transformants were identified on 1/2 MS medium containing 60 mg L-1 hygromycin.

The response of IbSWEET10 to Fusarium infection was investigated in ND98 plants. F. oxysporum was inoculated onto solid potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium at 28°C and cultured for 1 week in the dark. When the mycelium was fully expanded on the plate, the medium was minced, and the agar plugs were transferred to sterile distilled water and shaken for 2 h to loosen the spores from the mycelium surface. The resulting spore suspension was filtered through a nylon mesh to remove solid material; the spore concentration was determined using a haemocytometer and adjusted to ∼107 spores per mL. Before being grown in 19-cm-diameter pots containing sterile sandy loam, 20-cm-cuttings of ND98 with an apical bud from the field were soaked in spore suspension for 30 min. Each pot contained three cuttings as one treatment. All leaves of each treatment were collected at 0, 3, 5, 7, and 9 days post-inoculation (dpi), and expression of IbSWEET10 was assessed by qRT-PCR.

Subcellular Localization of IbSWEET10

The ORF of IbSWEET10 (stop codon deleted) was amplified using primers 83S-F/R and subcloned into a modified pMDC83 vector at SpeI and AscI restriction sites. The fusion construct (IbSWEET10-GFP) and the empty vector (GFP) were separately transformed into the EHA105 strain of Agrobacterium tumefaciens, and each transformant was co-infiltrated with a plasma membrane-localized marker (CD3-1007; Nelson et al., 2007) into the leaves of Nicotiana benthamiana, as previously described by Strasser et al. (2007). Furthermore, the sequence of IbSWEET10 with GFP was amplified from IbSWEET10-GFP fusion construct using primers SG-F/R and subcloned into the pDR196 vector at SmaI and XhoI restriction sites (Rentsch et al., 1995). The constructed vector was transformed into the sucrose transport deficient Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutant SUSY7/ura3 (Riesmeier et al., 1992) for subcellular localization assay. To select positive transformants, the transformed yeast cells were grown on yeast culture medium containing 6.7 g L-1 yeast nitrogen base, 2 g L-1 amino acid (uracil) drop out mix and 20 g L-1 glucose as the sole carbon source. The agroinfiltrated tobacco leaves and the yeast transformants were visualized with a laser scanning confocal microscope (Nikon Inc., Melville, NY, USA).

Functional Analysis of IbSWEET10 in Yeast

The ORF of IbSWEET10 was amplified using primers 196-F/R and then subcloned into the yeast expression vector pDR196 at SmaI and XhoI restriction sites (Rentsch et al., 1995). As a positive control, the AtSUT4 gene was also cloned into pDR196 (Weise et al., 2000). The constructed vectors and the empty vector were transformed into the sucrose transport deficient S. cerevisiae mutant SUSY7/ura3 (Riesmeier et al., 1992) for complementation assays. The positive transformants were selected as described above and were then cultured on medium containing 20 g L-1 sucrose to assess the function of IbSWEET10. The average diameters of yeast colonies were measured after 1 week using the ImageJ software. In addition, the hexose transport-deficient S. cerevisiae mutant EBY.VW4000 (Wieczorke et al., 1999) and drop tests were used to examine whether IbSWEET10 transports hexose. The transformants were grown overnight to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.6 in liquid medium containing 20 g L-1 maltose as the sole carbon source, and serial dilutions (OD600 = 0.6, 0.06, 0.006, 0.0006, and 0.00006) were plated on solid media containing different carbon sources (glucose, fructose, galactose, and mannose) for 1 week at 30°C.

Production of Transgenic Plants

To explore the function of IbSWEET10, the expression cassette P35S-IbSWEET10-TNOS was inserted into the plant binary vector pCAMBIA3301 at SacI and XbaI sites to generate the overexpression plasmid pCIbSWEET10. To construct the RNAi plasmid pFIbSWEET10, two fragments (FF and RF) were amplified from the coding sequence of IbSWEET10 using the primers Si-UF/R and Si-DF/R and inserted into the vector pFGC5941 at XhoI/SwaI and BamHI/XbaI sites, respectively. The sequence-verified plasmids pCIbSWEET10 and pFIbSWEET10 and the empty vector were separately transfected into A. tumefaciens strain EHA105. The transformation, regeneration, and overexpression lines (OX) identification of sweet potato cv. Lizixiang plants were performed as described by Wang et al. (2016). To identify IbSWEET10 RNAi lines, genomic DNA was extracted from the leaves of putative transgenic plants, and PCR was performed using the primers int-F/R. The transformants with the empty vector pCAMBIA3301 (VCo) and ones with the empty vector pFGC5941 (VCi) were used as the controls for the OX and RNAi lines, respectively.

Histochemical Analysis of GUS Activity

β-Glucuronidase reporter gene activity in transgenic Arabidopsis was examined by histochemical staining as described by Guo et al. (2014). The incubation time for whole seedlings, roots, and flowers was 2 h; 6 h was used for leaves, stems, siliques, and seeds.

In vitro Assay for Sucrose Tolerance

Transgenic and control sweet potato plants were cultured on solid MS medium with different sucrose concentrations (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6%) at 28±1°C under 16 h of cool-white fluorescent light at 54 μmol m-2 s-1. The standard sucrose concentration of MS medium is 3%. The growth status was observed after 4 weeks, and the fresh weight (FW) was measured immediately.

Inoculation of Transgenic Sweet Potato with F. oxysporum

Transgenic and control sweet potato plants were transferred to the soil in a greenhouse and a field and their 20-cm-cuttings were inoculated with F. oxysporum using the same methods described above to evaluate the resistance to F. oxysporum. Growth of the transgenic and control lines was evaluated at 9 or 7 dpi, and stem samples were collected for histological examination according to the method of Zhang et al. (2014).

Analysis of Sugar Content

To determine changes in sugar composition during Fusarium infection, leaves of transgenic and control plants were harvested at 0 and 9 dpi (or 7 dpi) for quantification of sucrose, glucose, and fructose using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC; Goodall et al., 1995). Briefly, leaves (0.5 g) were dissolved in 10 mL 80% ethanol, vortexed thoroughly and incubated at 70°C for 30 min. The mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 min, and the supernatant was collected into a new tube. The centrifugation step was repeated twice to remove any debris. The supernatant was dried at 70°C and redissolved into 5 mL distilled water, and 1 mL was filtered through a membrane (0.22 μm) and transferred to a glass tube for HPLC analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Three biological replicates were performed and the data were presented as the mean ± SE. Data difference analysis was carried out based on Student’s t-test (two-tailed analysis) at P < 0.01 or P < 0.05.

Results

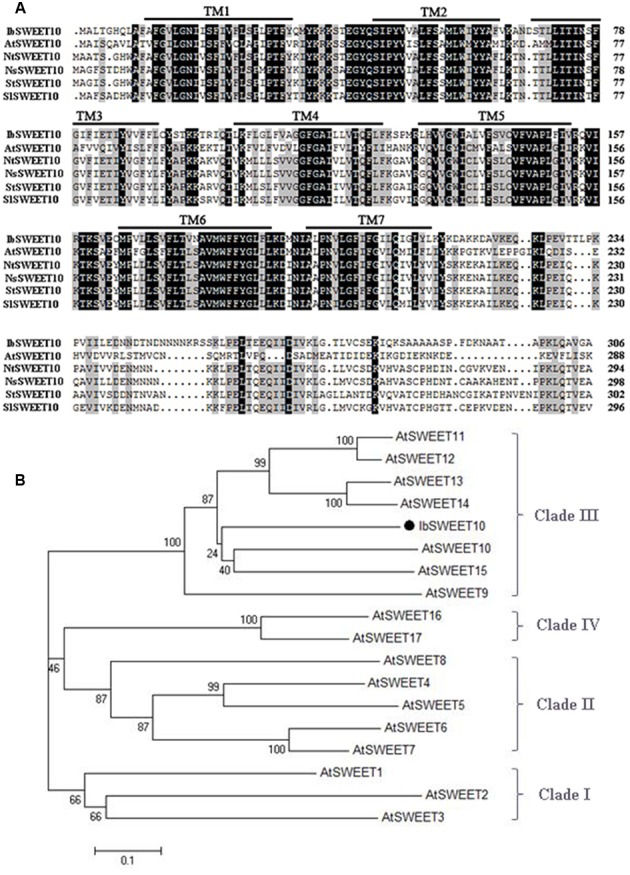

IbSWEET10 Encodes a Clade III SWEET Protein

A SWEET gene was cloned using the RACE method and we named it as IbSWEET10 based on its closest phylogenetic relationship with AtSWEET10 from A. thaliana (Eom et al., 2015). The cloned 1250-bp full-length IbSWEET10 cDNA contains a 921-bp ORF that encodes a 306-amino acid polypeptide with a molecular weight of 34.1 kDa and a pI of 9.34. A search of the IbSWEET10 protein sequence in NCBI revealed two conserved MtN3 domains. The genomic sequence of IbSWEET10 is 3269 bp long and contains six exons and five introns. The results of multiple sequence alignment show that the IbSWEET10 protein is a typical 7-TM SWEET (Figure 1A). Based on phylogenetic analysis, IbSWEET10 has the closest relationship with AtSWEET10 (Figure 1B), both belong to clade III of the SWEET family (Chen et al., 2010).

FIGURE 1.

Sequence analysis of IbSWEET10. (A) Multiple sequence alignment of sugar transporters from Ipomoea batatas (IbSWEET10), Arabidopsis thaliana (AtSWEET10, Q9LUE3.1), Nicotiana tabacum (NtSWEET10, XP_016465379), Nicotiana sylvestris (NsSWEET10, XP_009762335), Solanum tuberosum (StSWEET10, XP_015164326) and Solanum lycopersicum (SlSWEET10, XP_004235333). Identical amino acids are denoted by dark shading, and conserved amino acids are indicated by a gray background. The seven transmembrane (TM) domains are outlined. (B) Phylogenetic analysis of SWEET proteins from Ipomoea batatas (IbSWEET10) and Arabidopsis thaliana.

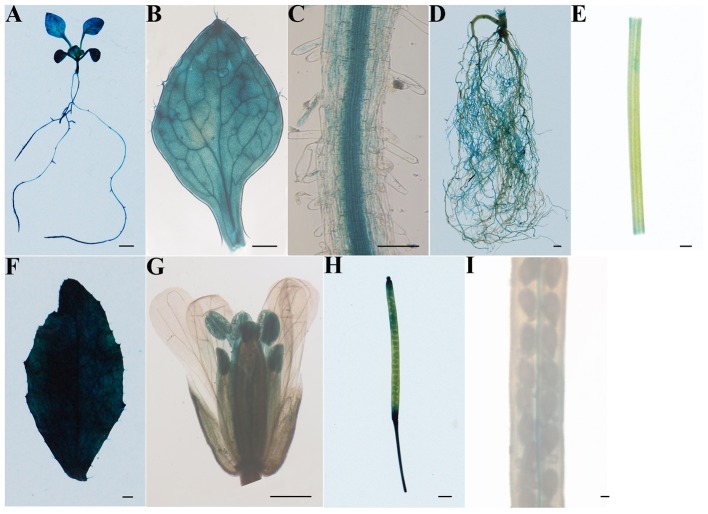

IbSWEET10 is Highly Expressed in Leaves

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis revealed expression level of IbSWEET10 was highest in leaves of 4-week-old in vitro-grown ND98 plants (Supplementary Figure S1A). High expression was also observed in leaves of 3-month-old ND98 plants from the field (Supplementary Figure S1B). As previously reported in sweet potato, the spatial expression pattern of a gene was correlated with its promoter activity in a heterologous system such as Arabidopsis (Noh et al., 2010, 2012; Tanabe et al., 2015). Therefore, the activity of the 1842 bp promoter including 5′UTR of IbSWEET10 was investigated in different tissues of Arabidopsis using gusA gene as a reporter gene. In 2-week-old seedlings of Arabidopsis, GUS activity driven by PIbSWEET10 was found in all of the tissues (Figure 2A), especially in the vascular tissues of leaves and roots (Figures 2B,C). In soil-grown mature Arabidopsis plants, the leaves showed the high GUS activity, but the reduced GUS activity was detected in roots, stems, flowers, siliques, and seeds (Figures 2D–I), which are consistent with IbSWEET10 expression in sweet potato.

FIGURE 2.

Tissue-specific localization of the IbSWEET10 protein in transgenic Arabidopsis identified by histochemical analysis of β-Glucuronidase (GUS) activity driven by the IbSWEET10 promoter. (A) 2-week-old seedling. (B,C) Leaf and root of a 2-week-old seedling. (D) Mature root. (E) Stem. (F) Leaf. (G) Flower. (H) Silique. (I) Seed. Bars = 1 mm (A,D–H), 0.05 mm (C), 0.1 mm (B,I).

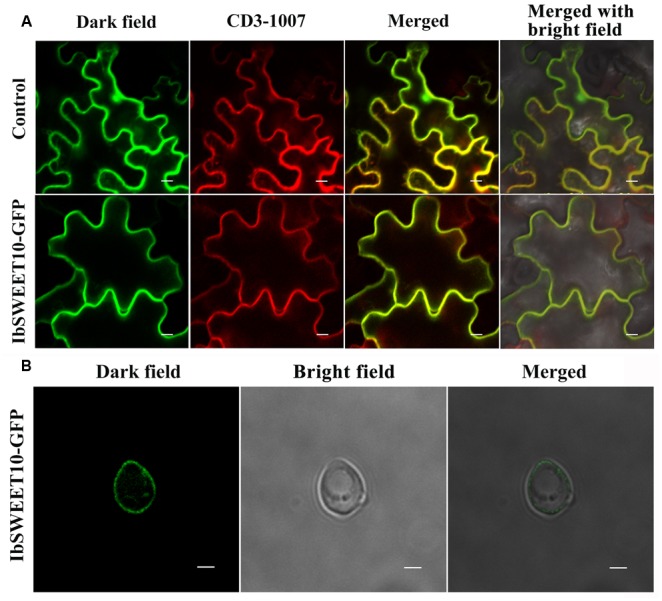

IbSWEET10 is Localized to the Plasma Membrane

In Arabidopsis, different SWEET proteins are localized to different cellular sites, and to date, four of the seven clade III AtSWEETs have been functionally shown to encode plasma membrane proteins (Seo et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2014; Chen L.Q. et al., 2015). Because IbSWEET10 is phylogenetically a clade III SWEET, we investigated whether it is also located in the plasma membrane by generating 2 × 35Spro-IbSWEET10-GFP construct and transient expression in N. benthamiana epidermal cells. As shown in Figure 3A, the green fluorescence emitted by the IbSWEET10-GFP fusion protein is coincident with the red fluorescence of the plasma membrane-localized marker CD3-1007, indicating that IbSWEET10 was localized to the plasma membrane. The subcellular localization in yeast further revealed that IbSWEET10 is a plasma membrane protein (Figure 3B).

FIGURE 3.

Subcellular localization of the IbSWEET10 protein. (A) The vector as a control (Upper row) and IbSWEET10-GFP (Lower row) protein were transiently expressed in N. benthamiana leaf hypodermal cells. The CD3-1007 marker was co-transformed to label the plasma membrane. Bars = 10 μm. (B) IbSWEET10-GFP protein was expressed in yeast cells. Bars = 2 μm.

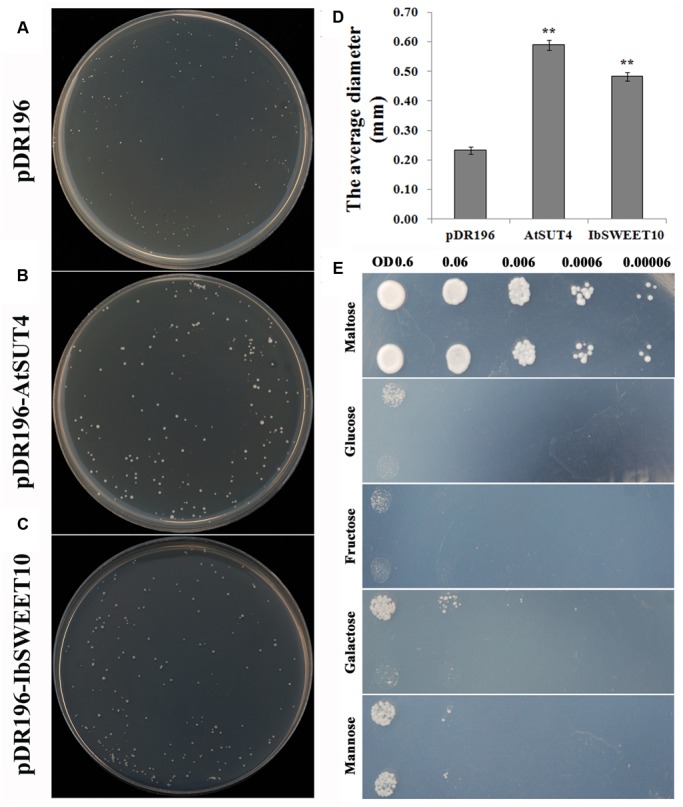

IbSWEET10 Transports Sucrose in Yeast

To investigate whether IbSWEET10 encodes a sugar transporter, the gene was expressed in the yeast mutant SUSY7/ura3, which is deficient in sucrose transport (Riesmeier et al., 1992). As shown in Figures 4A–C, SUSY7/ura3 cells expressing either AtSUT4 or IbSWEET10 grew better on sucrose media than the cells transformed with the empty pDR196 vector. The colonies transformed with IbSWEET10 were 2.09-folds of ones transformed with the empty pDR196 vector in size (Figure 4D). This was a strong indication that IbSWEET10 encodes a sucrose transporter. To examine whether IbSWEET10 transports hexose (glucose, fructose, galactose, and mannose), the yeast mutant EBY.VW4000 (Wieczorke et al., 1999), which is impaired in hexose transport, was transformed with IbSWEET10. However, no obvious signs of growth on media containing different hexoses as the main carbon source were observed (Figure 4E). These results revealed that IbSWEET10 is a sucrose transporter rather than a hexose transporter.

FIGURE 4.

Functional analysis of IbSWEET10 in the yeast mutant strain SUSY7/ura3 using sucrose as the main carbon source (A–D). Yeast mutant strain EBY.VW4000 growth on media with different carbon sources (E). (A) SUSY7/ura3 transformed with the empty pDR196 vector. (B) SUSY7/ura3 transformed with pDR196-AtSUT4 as the positive control. (C) SUSY7/ura3 transformed with pDR196-IbSWEET10. (D) The average diameters of yeast colonies grown after 1 week. (E) Growth complementation test of EBY.VW4000 transformed with the 614 empty pDR196 vector (Upper row) and pDR196-IbSWEET10 (Lower row) using different sugars as 615 carbon sources at degraded yeast OD value. Data are presented as the mean ± SE (n = 3). ∗∗ indicates a significant difference versus WT at P < 0.01 based on Student’s t-test.

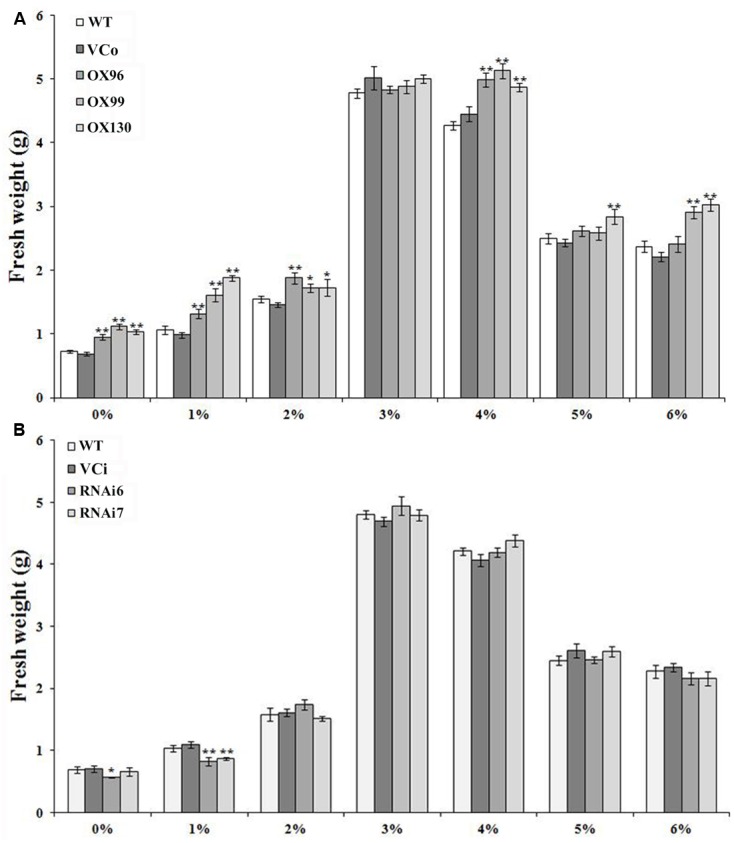

IbSWEET10 Affects Sucrose Tolerance of Sweet Potato Plants

Transgenic Lizixiang lines were generated as described by Wang et al. (2016) (Supplementary Figure S2). At last, the 11 OX, 8 RNAi, 5 VCo and 5 VCi transgenic lines were obtained in this study. qRT-PCR analysis showed significant increases in the transcript level of IbSWEET10 in three OX lines (OX96, OX99, and OX130; Supplementary Figure S3A) and dramatic decreases in two RNAi lines (RNAi6 and RNAi7; Supplementary Figure S3B) compared with WT and VCo/VCi. Under in vitro conditions, the sucrose concentration of the growth medium has an impact on the growth of plantlets (Jo et al., 2009). Because IbSWEET10 functions as a sucrose transporter, altered IbSWEET10 expression could affect sucrose transport and thereby alter plant growth. To examine this possibility, IbSWEET10 transgenic lines were grown on media containing different sucrose concentrations. Under a normal sucrose concentration (3%), both the OX and RNAi lines showed no difference in FW from WT and VCo/VCi. However, the OX lines exhibited enhanced tolerance to low (0–2%) or high (4%) sucrose concentrations compared with WT and VCo (Figure 5A). In contrast, low sucrose concentrations resulted in decreased FW in RNAi lines, whereas high sucrose concentrations caused little change compared with WT and VCi (Figure 5B).

FIGURE 5.

Responses of transgenic Lizixiang plants and control plants cultured on MS media supplemented with different sucrose concentrations. Fresh weights (FWs) were measured after 4 weeks of growth. (A) FWs of OX lines. (B) FWs of RNAi lines. Data are presented as the mean ± SE (n = 3). ∗ and ∗∗ indicate a significant difference versus WT at P < 0.05 or P < 0.01, respectively, based on Student’s t-test.

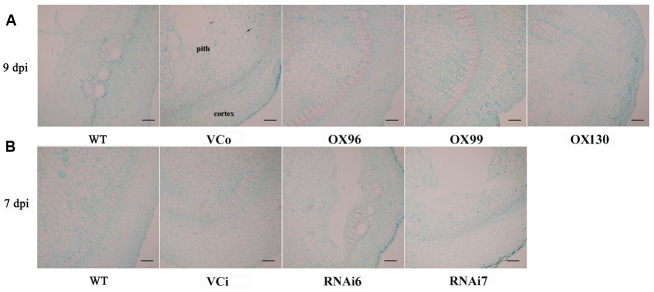

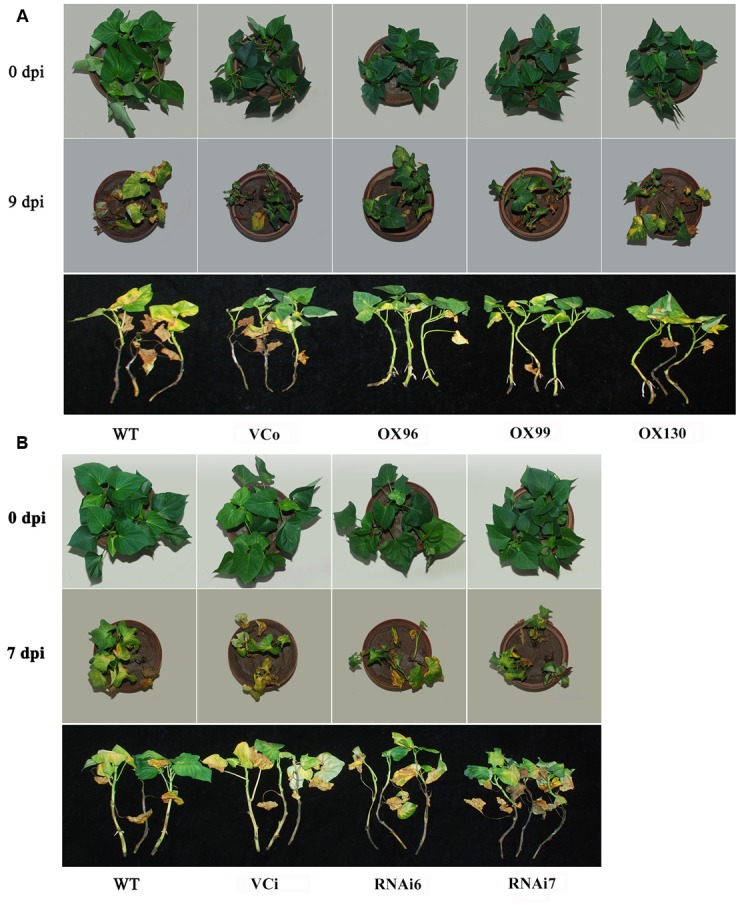

IbSWEET10 Plays a Positive Role in Resistance to F. oxysporum

To verify whether IbSWEET10 contributes to pathogen resistance, we first examined the changes in IbSWEET10 expression in ND98 plants infected by F. oxysporum. qRT-PCR analysis indicated that IbSWEET10 expression was significantly induced by the pathogen. The highest expression level was detected at 7 dpi: 3.46-fold of that at 0 dpi (Supplementary Figure S4). We further examined the severity of fusarium wilt in OX or RNAi lines at 9 or 7 dpi, respectively. At 9 dpi, almost half of the WT and VCo leaves were withered and yellow, whereas only a few OX leaves showed this symptom. The length of stem browning of the OX lines was also shorter than that of WT and VCo. Some new roots were formed on the OX stems, but no root formation was observed in WT and VCo (Figure 6A). Furthermore, RNAi lines exhibited more severe symptoms compared with WT and VCi, most of the leaves became wilted and yellow, the stems turned brown to black, and no root formation was found on the stems (Figure 6B). Histological observation of stems showed that the cells in the pith of WT and VCo were deformed and became loosely arranged, whereas the stem structure of OX lines remained intact, with compact cells in the pith and cortex (Figure 7A). Cross-sectional observation of the stems of RNAi lines exhibited a destroyed pith structure and distortion of cortex cells, which were not serious in WT and VCi (Figure 7B). These results indicate that IbSWEET10 plays a positive role in enhancing sweet potato resistance to F. oxysporum.

FIGURE 6.

Growth conditions of OX lines (A) and RNAi lines of Lizixiang (B) versus control plants at 0 and 9 dpi of F. oxysporum infection.

FIGURE 7.

Histological examination of transverse sections of stems of OX Lizixiang lines infected with F. oxysporum at 9 dpi (A) and the RNAi lines at 7 dpi (B). Black arrow indicated compact cells and red arrow indicated loose cells.

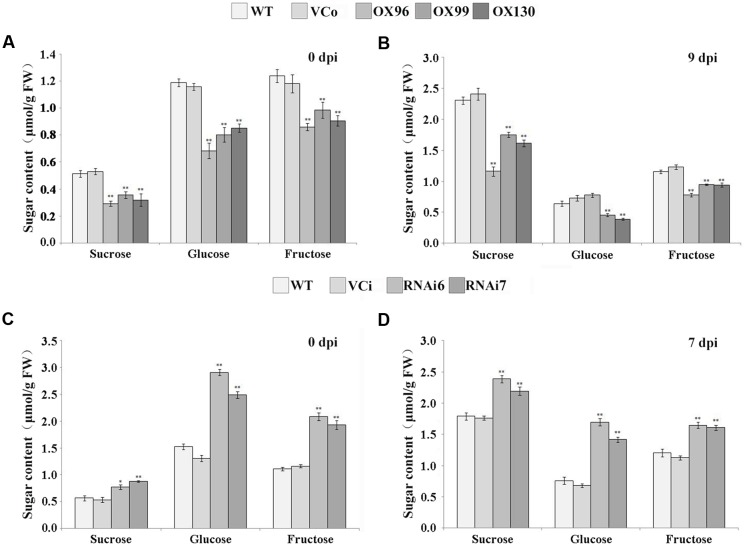

IbSWEET10 Is Associated with Sugar Contents in Sweet Potato

The carbohydrate status of plants affects the development/resistance of disease and vice versa (Berger et al., 2007; Gamm et al., 2011; Li et al., 2014). Because we identified the sucrose transporter activity of IbSWEET10, the altered resistance of transgenic plants to F. oxysporum was most likely caused by an uneven distribution of sucrose and other soluble sugars. Therefore, the sucrose, glucose and fructose contents in the leaves of transgenic and control plants were examined. For OX lines, a significant decrease in each of these three sugars was observed at both 0 and 9 dpi compared with WT and VCo (Figures 8A,B). However, RNAi lines contained higher levels of each sugar at 0 and 7 dpi compared with WT and VCi (Figures 8C,D). We also noticed that compared with 0 dpi, the sucrose content in each plant line was increased at 9 or 7 dpi.

FIGURE 8.

Sugar content in leaves of OX lines (A,B) and RNAi lines (C,D) of Lizixiang at 0 and 9 dpi of F. oxysporum infection, respectively. Data are presented as the mean ± SE (n = 3). ∗ and ∗∗ indicate a significant difference versus WT at P < 0.05 or P < 0.01, respectively, based on Student’s t-test.

Discussion

The Plasma Membrane Protein IbSWEET10 Is a Sucrose Transporter

Sugars Will Eventually be Exported Transporters have been demonstrated to have sugar transport capacity, mainly transporting sucrose and glucose in many plants (Chen et al., 2010; Chen L.Q. et al., 2015). In the present study, assays using sucrose transport-deficient yeast SUSY7/ura3 cells revealed that IbSWEET10 is a sucrose transporter (Figure 4). Based on expression in hexose transport-deficient yeast EBY.VW4000 cells, IbSWEET10 did not transport glucose, fructose, galactose or mannose (Figure 4D). This result is consistent with other reported SWEETs that belong to clade III (Chen L.Q. et al., 2015).

It is reported that the physiological role of sucrose transporters can be predicted through analysis of their tissue-specific expression and subcellular localization. The most possible route of sucrose transport into the SE/CC might begin directly from its production site in mesophyll cells through the apoplasm and into phloem parenchyma cells (Chen et al., 2012). Analysis of the GUS expression patterns of PIbSWEET10-GUS-transgenic Arabidopsis revealed that IbSWEET10 is more abundantly expressed in leaves of mature plants, especially in vascular tissues (Figure 2F). This finding indicates that IbSWEET10 functions to export sucrose from source leaves and participates in phloem loading. A two-step model of sucrose apoplasmic phloem loading shows that sucrose is exported by SWEETs residing in the plasma membrane of phloem parenchyma cells and feeds the sucrose transporter SUT in the SE/CC (Chen et al., 2012). Our study reveals that IbSWEET10 is located in the plasma membrane (Figure 3). Thus, we suggest that IbSWEET10 participates in the first step of sucrose apoplasmic phloem loading across the plasma membrane.

Overexpression of IbSWEET10 Increases Tolerance of Sweet Potato to Sucrose

Plants growing under tissue culture conditions are semiautotrophic, and supplementation of sucrose in the medium meets the energy demand for growth and physiological functions (Hazarika, 2003). The atsweet11;12 mutants show reduced root length when germinated on sugar-free media (Chen et al., 2012) and atsuc2 mutant seedlings are smaller than wild-type under the same conditions (Gottwald et al., 2000). In this study, a significant increase in fresh weigh of the OX plants was observed compared with the controls under low sucrose concentration (0–2%), suggesting that overexpression of IbSWEET10 increases the efflux of sucrose from leaves and promotes the plant growth (Figure 5A). Under high sucrose concentration (4%), the OX plants also exhibited the increased FW compared with the controls, thinking that its overexpression might facilitate sucrose transport into the OX plant roots from leaves and medium, which induces osmotic stress balance in the rhizosphere (Jo et al., 2009; Chen L.Q. et al., 2015). However, when expression of IbSWEET10 was suppressed, low sucrose concentrations in the medium caused the decreased FW in RNAi plants. No significant difference in FW was observed between RNAi plants and controls at high sucrose concentrations (Figure 5B). One possible explanation for this result is that reduced expression of IbSWEET10 might lead to impaired export of sucrose from leaves and thus negatively affect the plant growth (Burkle et al., 1998). When the sucrose supply was sufficient, the RNAi plants were able to acquire sucrose from the medium for growth.

Overexpression of IbSWEET10 Enhances Resistance of Sweet Potato to F. oxysporum

Access to nutrients from hosts for reproduction is the primary objective of infection (Chen et al., 2010), and sugars are among the most important nutrients providing energy for pathogen growth. For many diseases caused by soil pathogens, the nutrients provided by the host are considered to be a main factor in deciding the success or failure of symptomatic development (Hancock and Huisman, 1981). The observed high incidence of Fusarium with the shrunken-2 mutation was proposed to result from the elevated sugar content in kernels (Headrick et al., 1990). Additionally, AtSWEET2 activity reduced sugar availability in the rhizosphere, thus contributing to Pythium resistance (Chen H.Y. et al., 2015). Thus, lack of carbohydrates will limit the growth of a pathogenic fungus and reduce the ability of the pathogen to infect plants.

Alteration of the expression levels of sucrose transporter genes might cause changes in the sugar content in plants. Leaves of atsweet11:12 double mutants accumulate high levels of sugars, indicating an impaired ability to export sugar from the leaves (Chen et al., 2012). In addition, disruption of AtSUC4 or AtSUC2 caused sucrose accumulation in source leaves possibly by interfering with phloem loading (Gong et al., 2015), and the sucrose concentration in the vacuole of PatSUT4-RNAi lines was higher than in WT under well-watered conditions (Frost et al., 2012). In our study, overexpression of IbSWEET10 might enhance sugar export from leaves, which can explain the lower sugar contents in the leaves of OX plants. The opposite was observed for RNAi plants (Figure 8A). Long-distance transport of sucrose between leaves and roots occurs in the phloem sieve elements of the stem vascular system (Williams et al., 2000), and blocked phloem loading causes more accumulation of sugars in leaves (Chen et al., 2012). After F. oxysporum infection, the stems of OX plants displayed only slight damage and phloem loading block, which facilitated the transport of sugars from the leaves compared with WT, VCo, VCi and RNAi plants which showed serious damage and phloem loading block (Figure 7). As a result, the sucrose content was significantly decreased in the OX leaves than in others after F. oxysporum infection (Figures 8B,D). These results indicated that IbSWEET10 plays an important role in sugar transport in sweet potato plants.

The soil-borne F. oxysporum proliferates in the vascular of sweet potato stems and then spreads to the leaves, which causes wilting of stems and leaves. Therefore, the lower level of sugars in the OX stems and leaves might limit the proliferation of the pathogen. Meanwhile, closely arranged cell structure of OX stems might prevent the invasion and spread of F. oxysporum. As a result, the OX plants exhibited the enhanced resistance to F. oxysporum (Figure 6).

In addition, the overexpression of OsSWEET11, -13, and -14 enhanced the pathogenicity of X. oryzae in rice (Yang et al., 2006; Antony et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2011). The AtSWEET2-overexpressing Arabidopsis plants showed the increased resistance to P. irregulare (Chen H.Y. et al., 2015). Our results revealed that overexpression of IbSWEET10 enhanced the resistance of sweet potato to F. oxysporum. Therefore, it is thought that different members of the SWEET gene family differentially function in the responses to plant pathogens.

Conclusion

A member of the SWEET gene family named IbSWEET10, a sucrose transporter gene, was cloned from the sweet potato line ND98. Its overexpression significantly enhanced resistance to F. oxysporum in transgenic sweet potato plants. We suggest that the reduced sugar levels caused by overexpression of IbSWEET10 may decrease the carbohydrate supply for the pathogen and thus contribute to enhanced resistance to F. oxysporum in sweet potato. The IbSWEET10 gene has the great potential to be used for improving the resistance to F. oxysporum in sweet potato and other plants.

Author Contributions

SH, QL, and YL conceived and designed the experiments. YL, YW, HuZ, and QZ performed the experiments. YL, SH, YW, and HoZ analyzed the data and wrote the paper. SH and QL revised the paper. All authors read and approved the final version of the paper.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to professor Eckhard Boles for providing yeast strain EBY.VW4000 and to Professor Wolf B. Frommer for providing yeast strain SUSY7/ura3 and the vector pDR196.

Funding. This research was financially supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 31371680), the Beijing Food Crops Innovation Consortium Program (BAIC09-2016) and the China Agriculture Research System (CARS-11).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2017.00197/full#supplementary-material

References

- Antony G., Zhou J., Huang S., Li T., Liu B., White F., et al. (2010). Rice xa13 recessive resistance to bacterial blight is defeated by induction of the disease susceptibility gene Os-11N3. Plant Cell 22 3864–3876. 10.1105/tpc.110.078964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker R. (1968). Mechanisms of biological control of soil-borne pathogens. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 6 263–294. 10.1146/annurev.py.06.090168.001403 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baud S., Wuilleme S., Lemoine R., Kronenberger J., Caboche M., Lepiniec L. (2005). The AtSUC5 sucrose transporter specifically expressed in the endosperm is involved in early seed development in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 43 824–836. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02496.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger S., Sinha A. K., Roitsch T. (2007). Plant physiology meets phytopathology: plant primary metabolism and plant-pathogen interactions. J. Exp. Bot. 58 4019–4026. 10.1093/jxb/erm298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boorer K. J., Loo D. D., Frommer W. B., Wright E. M. (1996). Transport mechanism of the cloned potato H+/sucrose cotransporter StSUT1. J. Biol. Chem. 271 25139–25144. 10.1074/jbc.271.41.25139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkle L., Hibberd J. M., Quick W. P., Kuhn C., Hirner B., Frommer W. B. (1998). The H+-sucrose cotransporter NtSUT1 is essential for sugar export from tobacco leaves. Plant Physiol. 118 59–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büttner M. (2007). The monosaccharide transporter (-like) gene family in Arabidopsis. FEBS Lett. 581 2318–2324. 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H. Y., Huh J. H., Yu Y. C., Ho L. H., Chen L. Q., Tholl D., et al. (2015). The Arabidopsis vacuolar sugar transporter SWEET2 limits carbon sequestration from roots and restricts Pythium infection. Plant J. 83 1046–1058. 10.1111/tpj.12948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L. Q., Cheung L. S., Feng L., Tanner W., Frommer W. B. (2015). Transport of sugars. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 84 865–894. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-033904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L. Q., Hou B. H., Lalonde S., Takanaga H., Hartung M. L., Qu X. Q., et al. (2010). Sugar transporters for intercellular exchange and nutrition of pathogens. Nature 468 527–532. 10.1038/nature09606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L. Q., Qu X. Q., Hou B. H., Sosso D., Osorio S., Fernie A. R., et al. (2012). Sucrose efflux mediated by SWEET proteins as a key step for phloem transport. Science 335 207–211. 10.1126/science.1213351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark C. A. (1994). The chlorotic leaf distortion pathogen, Fusarium lateritium, cross protects sweetpotato against fusarium wilt caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. batatas. Biol. Control 4 59–66. 10.1006/bcon.1994.1011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark C. A., Hyun J. W., Hoy M. W. (1998). Relationships among wilt-inducing isolates of Fusarium oxysporum from sweetpotato and tobacco. Plant Dis. 82 530–536. 10.1094/pdis.1998.82.5.530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough S. J., Bent A. F. (1998). Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16 735–743. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhandapani P., Song J. C., Novak O., Jameson P. E. (2016). Infection by Rhodococcus fascians maintains cotyledons as a sink tissue for the pathogen. Ann. Bot. 10.1093/aob/mcw202 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel M. L., Davis R. H., McCormick S. (2005). Green sperm. Identification of male gamete promoters in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 138 2124–2133. 10.1104/pp.104.054213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eom J. S., Chen L. Q., Sosso D., Julius B. T., Lin I. W., Qu X. Q., et al. (2015). SWEETs, transporters for intracellular and intercellular sugar translocation. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 25 53–62. 10.1016/j.pbi.2015.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eveland A. L., Jackson D. P. (2012). Sugars, signalling, and plant development. J. Exp. Bot. 63 3367–3377. 10.1093/jxb/err379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng C. H., Yin Z. F., Ma Y. L., Zhang Z. B., Chen L., Wang B. A., et al. (2011). Cryopreservation of sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas) and its pathogen eradication by cryotherapy. Biotechnol. Adv. 29 84–93. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2010.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein R. R., Lynch T. J. (2000). Abscisic acid inhibition of radicle emergence but not seedling growth is suppressed by sugars. Plant Physiol. 122 1179–1186. 10.1104/pp.122.4.1179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forde B. G. (2002). The role of long-distance signalling in plant responses to nitrate and other nutrients. J. Exp. Bot. 53 39–43. 10.1093/jexbot/53.366.39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost C. J., Nyamdari B., Tsai C. J., Harding S. A. (2012). The tonoplast-localized sucrose transporter in Populus (PtaSUT4) regulates whole-plant water relations, responses to water stress, and photosynthesis. PLoS ONE 7:e44467 10.1371/journal.pone.0044467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamm M., Heloir M. C., Bligny R., Vaillant-Gaveau N., Trouvelot S., Alcaraz G., et al. (2011). Changes in carbohydrate metabolism in Plasmopara viticola-infected grapevine leaves. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 24 1061–1073. 10.1094/mpmi-02-11-0040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson S. I. (2000). Plant sugar-response pathways. Part of a complex regulatory web. Plant Physiol. 124 1532–1539. 10.1104/pp.124.4.1532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong X., Liu M. L., Zhang L. J., Ruan Y. Y., Ding R., Ji Y. Q., et al. (2015). Arabidopsis AtSUC2 and AtSUC4, encoding sucrose transporters, are required for abiotic stress tolerance in an ABA-dependent pathway. Physiol. Plant. 153 119–136. 10.1111/ppl.12225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodall I., Dennis M. J., Parker I., Sharman M. (1995). Contribution of high-performance liquid chromatographic analysis of carbohydrates to authenticity testing of honey. J. Chromatogr. A 706 353–359. 10.1016/0021-9673(94)01074-O [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gottwald J. R., Krysan P. J., Young J. C., Evert R. F., Sussman M. R. (2000). Genetic evidence for the in planta role of phloem-specific plasma membrane sucrose transporters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 13979–13984. 10.1073/pnas.250473797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y. F., Huang X. Y., Zhu J., Gao J. F., Zhang H. X., Yang Z. N. (2008). RUPTURED POLLEN GRAIN1, a member of the MtN3/saliva gene family, is crucial for exine pattern formation and cell integrity of microspores in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 147 852–863. 10.1104/pp.108.118026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W. J., Nagy R., Chen H. Y., Pfrunder S., Yu Y. C., Santelia D., et al. (2014). SWEET17, a facilitative transporter, mediates fructose transport across the tonoplast of Arabidopsis roots and leaves. Plant Physiol. 164 777–789. 10.1104/pp.113.232751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock J. G., Huisman O. C. (1981). Nutrient movement in host-pathogen systems. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 19 309–331. 10.1146/annurev.py.19.090181.001521 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hazarika B. N. (2003). Acclimatization of tissue-cultured plants. Curr. Sci. India 85 1704–1712. [Google Scholar]

- Headrick J. M., Pataky J. K., Juvik J. A. (1990). Relationships among carbohydrate content of kernels, condition of silks after pollination, and the response of sweet corn inbred lines to infection of kernels by Fusarium moniliforme. Phytopathology 80 487–494. 10.1094/Phyto-80-487 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y. B., Sosso D., Qu X. Q., Chen L. Q., Ma L., Chermak D., et al. (2016). Phylogenetic evidence for a fusion of archaeal and bacterial SemiSWEETs to form eukaryotic SWEETs and identification of SWEET hexose transporters in the amphibian chytrid pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. FASEB J. 30 3644–3654. 10.1096/fj.201600576R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y. D., Li C. Y., Qi Y. P., Park S., Gibson S. I. (2014). SIS8, a putative mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase, regulates sugar-resistant seedling development in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 77 577–588. 10.1111/tpj.12404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibraheem O., Dealtry G., Roux S., Bradley G. (2011). The effect of drought and salinity on the expressional levels of sucrose transporters in rice (Oryza sativa Nipponbare) cultivar plants. Plant Omics 4 68–74. [Google Scholar]

- Jameson P. E., Dhandapani P., Novak O., Song J. C. (2016). Cytokinins and expression of SWEET, SUT, CWINV and AAP genes increases as pea seeds germinate. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17:2013 10.3390/ijms17122013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo E. A., Tewari R. K., Hahn E. J., Paek K. Y. (2009). In vitro sucrose concentration affects growth and acclimatization of Alocasia amazonica plantlets. Plant Cell Tiss. Org. Cult. 96 307–315. 10.1007/s11240-008-9488-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanno Y., Oikawa T., Chiba Y., Ishimaru Y., Shimizu T., Sano N., et al. (2016). AtSWEET13 and AtSWEET14 regulate gibberellin-mediated physiological processes. Nat. Commun. 7:13245 10.1038/ncomms13245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane P. (2012). How pathogens attack plants. Microbiol. Aust. 33 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Khoury C. K., Heider B., Castañeda-Álvarez N. P., Achicanoy H. A., Sosa C. C., Miller R. E., et al. (2015). Distributions, ex situ conservation priorities, and genetic resource potential of crop wild relatives of sweetpotato [Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam., I. series Batatas]. Front. Plant Sci. 6:251 10.3389/fpls.2015.00251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemens P. A. W., Patzke K., Deitmer J., Spinner L., Le Hir R., Bellini C., et al. (2013). Overexpression of the vacuolar sugar carrier AtSWEET16 modifies germination, growth, and stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 163 1338–1352. 10.1104/pp.113.224972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch K. E. (1996). Carbohydrate-modulated gene expression in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 47 509–540. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.47.1.509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalonde S., Wipf D., Frommer W. B. (2004). Transport mechanisms for organic forms of carbon and nitrogen between source and sink. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 55 341–372. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemoine R., La Camera S., Atanassova R., Dédaldéchamp F., Allario T., Pourtau N., et al. (2013). Source-to-sink transport of sugar and regulation by environmental factors. Front. Plant Sci. 4:272 10.3389/Fpls.2013.00272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Gao L., Wang Y. T., Zhu W., Ye J. L., Li G. H. (2014). Carbohydrate metabolism changes in Prunus persica gummosis infected with Lasiodiplodia theobromae. Phytopathology 104 445–452. 10.1094/Phyto-01-13-0025-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin I. W., Sosso D., Chen L. Q., Gase K., Kim S. G., Kessler D., et al. (2014). Nectar secretion requires sucrose phosphate synthases and the sugar transporter SWEET9. Nature 508 546–549. 10.1038/nature13082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q. S., Yuan M., Zhou Y., Li X. H., Xiao J. H., Wang S. P. (2011). A paralog of the MtN3/saliva family recessively confers rece-specific resistance to Xanthomonas oryzae in rice. Plant Cell Environ. 34 1958–1969. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02391.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. Z., Zhang Y., Yang C., Tian Z. H., Li J. X. (2016). AtSWEET4, a hexose facilitator, mediates sugar transport to axial sinks and affects plant development. Sci. Rep. 6:24563 10.1038/Srep24563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marger M. D., Saier M. H. (1993). A major superfamily of transmembrane facilitators that catalyze uniport, symport and antiport. Trends Biochem. Sci. 18 13–20. 10.1016/0968-0004(93)90081-W [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullerrober B., Sonnewald U., Willmitzer L. (1992). Inhibition of the ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase in transgenic potatoes leads to sugar-storing tubers and influences tuber formation and expression of tuber storage protein genes. EMBO J. 11 1229–1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson B. K., Cai X., Nebenführ A. (2007). A multicolored set of in vivo organelle markers for co-localization studies in Arabidopsis and other plants. Plant J. 51 1126–1136. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03212.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noh S. A., Lee H.-S., Huh E. J., Huh G. H., Paek K.-H., Shin J. S., et al. (2010). SRD1 is involved in the auxin-mediated initial thickening growth of storage root by enhancing proliferation of metaxylem and cambium cells in sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas). J. Exp. Bot. 61 1337–1349. 10.1093/jxb/erp399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noh S. A., Lee H.-S., Huh G. H., Oh M.-J., Paek K.-H., Shin J. S., et al. (2012). A sweetpotato SRD1 promoter confers strong root-, taproot-, and tuber-specific expression in Arabidopsis, carrot, and potato. Transgenic Res. 21 265–278. 10.1007/s11248-011-9528-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noiraud N., Delrot S., Lemoine R. (2000). The sucrose transporter of celery. Identification and expression during salt stress. Plant Physiol. 122 1447–1455. 10.1104/pp.122.4.1447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil G., Valliyodan B., Deshmukh R., Prince S., Nicander B., Zhao M. Z., et al. (2015). Soybean (Glycine max) SWEET gene family: insights through comparative genomics, transcriptome profiling and whole genome re-sequence analysis. BMC Genomics 16:520 10.1186/s12864-015-1730-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rentsch D., Laloi M., Rouhara I., Schmelzer E., Delrot S., Frommer W. B. (1995). NTR1 encodes a high affinity oligopeptide transporter in Arabidopsis. FEBS Lett. 370 264–268. 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00853-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riesmeier J. W., Willmitzer L., Frommer W. B. (1992). Isolation and characterization of a sucrose carrier cDNA from spinach by functional expression in yeast. EMBO J. 11 4705–4713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roitsch T., Gonzalez M. C. (2004). Function and regulation of plant invertases: sweet sensations. Trends Plant Sci. 9 606–613. 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roldán M., Gómez-Mena C., Ruiz-García L., Salinas J., Martínez-Zapater J. M. (1999). Sucrose availability on the aerial part of the plant promotes morphogenesis and flowering of Arabidopsis in the dark. Plant J. 20 581–590. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1999.00632.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolland F., Baena-Gonzalez E., Sheen J. (2006). Sugar sensing and signaling in plants: conserved and novel mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 57 675–709. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer N., Friedlander K., Gramlwicke U. (1990). Primary structure, genomic organization and heterologous expression of a glucose transporter from Arabidopsis thaliana. EMBO J. 9 3045–3050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer N., Stolz J. (1994). SUC1 and SUC2: two sucrose transporters from Arabidopsis thaliana; expression and characterization in baker’s yeast and identification of the histidine-tagged protein. Plant J. 6 67–77. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1994.6010067.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo P. J., Park J. M., Kang S. K., Kim S. G., Park C. M. (2011). An Arabidopsis senescence-associated protein SAG29 regulates cell viability under high salinity. Planta 233 189–200. 10.1007/s00425-010-1293-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivitz A. B., Reinders A., Johnson M. E., Krentz A. D., Grof C. P. L., Perroux J. M., et al. (2007). Arabidopsis sucrose transporter AtSUC9. High-affinity transport activity, intragenic control of expression, and early flowering mutant phenotype. Plant Physiol. 143 188–198. 10.1104/pp.106.089003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivitz A. B., Reinders A., Ward J. M. (2008). Arabidopsis sucrose transporter AtSUC1 is important for pollen germination and sucrose-induced anthocyanin accumulation. Plant Physiol. 147 92–100. 10.1104/pp.108.118992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosso D., Luo D. P., Li Q.-B., Sasse J., Yang J. L., Gendrot G., et al. (2015). Seed filling in domesticated maize and rice depends on SWEET-mediated hexose transport. Nat. Genet. 47 1489–1493. 10.1038/ng.3422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava A. C., Ganesan S., Ismail I. O., Ayre B. G. (2008). Functional characterization of the Arabidopsis AtSUC2 sucrose/H+ symporter by tissue-specific complementation reveals an essential role in phloem loading but not in long-distance transport. Plant Physiol. 148 200–211. 10.1104/pp.108.124776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser R., Singh J., Bondili J. S., Schoberer J., Svoboda B., Liebminger E., et al. (2007). Enzymatic properties and subcellular localization of Arabidopsisβ-N-acetylhexosaminidases. Plant Physiol. 145 5–16. 10.1104/pp.107.101162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe N., Tamoi M., Shigeoka S. (2015). The sweet potato RbcS gene (IbRbcS1) promoter confers high-level and green tissue-specific expression of the GUS reporter gene in transgenic Arabidopsis. Gene 567 244–250. 10.1016/j.gene.2015.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. N., Li Y., Zhang H., Zhai H., Liu Q. C., He S. Z. (2016). A plastidic ATP/ADP transporter gene, IbAATP, increases starch and amylose contents and alters starch structure in transgenic sweetpotato. J. Integr. Agric. 15 1968–1982. 10.1016/s2095-3119(15)61192-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weise A., Barker L., Kuhn C., Lalonde S., Buschmann H., Frommer W. B., et al. (2000). A new subfamily of sucrose transporters. SUT4, with low affinity/high capacity localized in enucleate sieve elements of plants. Plant Cell 12 1345–1355. 10.1105/tpc.12.8.1345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieczorke R., Krampe S., Weierstall T., Freidel K., Hollenberg C. P., Boles E. (1999). Concurrent knock-out of at least 20 transporter genes is required to block uptake of hexoses in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 464 123–128. 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)01698-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams L. E., Lemoine R., Sauer N. (2000). Sugar transporters in higher plants - a diversity of roles and complex regulation. Trends Plant Sci. 5 283–290. 10.1016/S1360-1385(00)01681-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xuan Y. H., Hu Y. B., Chen L. Q., Sosso D., Ducat D. C., Hou B.-H., et al. (2013). Functional role of oligomerization for bacterial and plant SWEET sugar transporter family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 E3685–E3694. 10.1073/pnas.1311244110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B., Sugio A., White F. F. (2006). Os8N3 is a host disease-susceptibility gene for bacterial blight of rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103 10503–10508. 10.1073/pnas.0604088103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan M., Wang S. P. (2013). Rice MtN3/Saliva/SWEET family genes and their homologs in cellular organisms. Mol. Plant 6 665–674. 10.1093/mp/sst035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai H., Wang F. B., Si Z. Z., Huo J. X., Xing L., An Y. Y., et al. (2016). A myo-inositol-1-phosphate synthase gene. IbMIPS1, enhances salt and drought tolerance and stem nematode resistance in transgenic sweet potato. Plant Biotechnol. J. 14 592–602. 10.1111/pbi.12402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G. H., Li S. Y., Wang L., Ye W. J., Zeng D. L., Rao Y. C., et al. (2014). LSCHL4 from Japonica cultivar, which is allelic to NAL1, increases yield of Indica super rice 93-11. Mol. Plant 7 1350–1364. 10.1093/mp/ssu055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K., Wu Z. D., Tang D. B., Lv C. W., Luo K., Zhao Y., et al. (2016). Development and identification of SSR markers associated with starch properties and β-carotene content in the storage root of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.). Front. Plant Sci. 7:223 10.3389/fpls.2016.00223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., Theodoulou F., Sauer N., Sanders D., Miller A. J. (1997). A kinetic model with ordered cytoplasmic dissociation for SUC1, an Arabidopsis H+/sucrose cotransporter expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J. Membrane Biol. 159 113–125. 10.1007/s002329900275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Liu L., Huang W. F., Yuan M., Zhou F., Li X. H., et al. (2014). Overexpression of OsSWEET5 in rice causes growth retardation and precocious senescence. PLoS ONE 9:e94210 10.1371/journal.pone.0094210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.