Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the association between serum complement 5a (C5a) concentration and liver fibrosis and cirrhosis in a large cohort of patients chronically infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV).

Methods

Five hundred and eight patients with chronic HBV infection undergoing liver biopsy were included. Serum concentrations of C5a was measured by Luminex screening system. Ishak histological system was obtained.

Results

C5a levels were negatively associated with liver fibrosis stages and significantly declined in patients with severe fibrosis and cirrhosis (P < 0.001). Multiple analysis showed C5a, AST, laminin, Co-IV, platelet count, albumin, HBsAg associated with liver fibrosis independently. Based on the markers above, we created two scores, Fib-model for significant fibrosis and Cirrh-model for earlier cirrhosis. Fib-model was performing better to differentiate from significant fibrosis, with an AUROC of 0.82 (95 % CI 0.78, 0.86), in comparison to existed models APRI, FIB-4 and Forns’ index with AUROCs of 0.71 (95 % CI 0.66, 0.76), 0.72 (95 % CI 0.67, 0.77), 0.77 (95 % CI 0.72, 0.81), respectively. Although, Cirrh-model showed AUROC of 0.85 (95 % CI 0.80, 0.91) for evaluation of earlier cirrhosis, superior to APRI, and Forns’ index, C5a + FIB-4 performed best with an AUROC of 0.94 (95 % CI 0.90, 0.97).

Conclusion

In patients with chronic HBV infection, serum C5a concentration significantly decreased in severe fibrosis stages and earlier cirrhosis. Fib-model and C5a + FIB-4 performed better than existed models for assessment of significant fibrosis and earlier cirrhosis, respectively.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s15010-016-0942-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Complement 5a, Hepatitis B, Liver fibrosis, Cirrhosis

Introduction

Chronic HBV infection was a serious health problem affecting approximately 5 % of the world’s population, which could further develop cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [1]. Liver fibrosis was part of the natural wound healing response to parenchymal injury and generally considered to be a key event resulting in cirrhosis. The accurate assessment of liver fibrosis staging should enable clinical physicians to determine individual management and monitor the disease progression. Liver biopsy remained the gold standard for assessing fibrosis and cirrhosis, however, up to 2 % of patients develop complications from this procedure [2]. The cost, invasiveness and risks associated with liver biopsy limited its use for disease assessment and monitoring.

In the past decade, non-invasive methods for assessment of liver fibrosis have been developed as surrogates to liver biopsy, based on a “biological” approach (quantifying biomarkers in serum samples) or based on a “physical” approach (measuring liver stiffness) [3, 4]. Compared with liver stiffness measurement, serum biomarkers included such advantages as high applicability (95 %), good inter-laboratory reproducibility and widespread availability [5–7].

Complement 5 (C5), a serum protein that is an integral component of the complement activation cascade, generate two distinct products upon proteolytic leavage: C5b leading to the formation of a lytic membrane attack complex (MAC), and C5a [8]. C5a was first described as an anaphylatoxin and later as a leukocyte chemoattractant, and recently was also implicated in non-immunological functions associated with development biology, neurodegeneration, tissue regeneration, and haematopoiesis [9]. In liver, C5a receptor (C5aR) was shown to be universally expressed on the surface of Rat Kupffer (KC), hepatic stellate cell (HSC) and sinusoidal endothelial cells (SEC), which were known to play a key role in the induction of liver fibrosis [10]. The Study by Xu Ruonan and their colleagues indicated that C5a significantly activated HSCs and up-regulated α-smooth muscle actin, hyaluronic acid and type IV collagen expression [11]. Another study showed up-regulation of fibronectin but not entactin, collagen IV and smooth muscle actin by anaphylatoxin C5a in rat HSCs [10]. It was reported that small molecule inhibitors of the C5a receptor had antifibrotic effects in vivo, and common haplotype-tagging polymorphisms of the human gene C5 were associated with advanced fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C virus infection [12]. Recently, plasma C5a concentration has been reported increasing in 73 chronic hepatitis B patients than in 17 healthy control subjects, particularly in those patients with higher inflammation grade and fibrosis stage [11]. However, the small sample size was the main drawback of the study. Additionally, the cohort contained some patients who were receiving antiviral treatment, which may contribute to inaccurate analysis. In fact, the performance of C5a as an potential biomarker for predicting liver fibrosis stages has not been fully identified.

This study was designed to investigate the association between serum C5a concentration and liver fibrosis and cirrhosis in a large cohort of patients chronically infected with HBV.

Patients and methods

Patients

This study included 508 patients with chronic HBV infection from 24 hospitals described previously [13] in mainland of China between October of 2014 and October of 2015 and 18 patients from Southwest medical University T.C.M hospital. All patients were recruited for China HepB Related Fibrosis Assessment Research supported by China Mega-project for Infectious Diseases. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were previously described [13]. All patients gave written informed consent to entry to the project for use of clinical data and specimens for research purpose. The full, detailed clinical trials protocol was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01962155) and chictr.org (ChiCTR-DDT-13003724). The study was approved by The Ethical Committees of Peking University First Hospital.

Laboratory test

Biochemical and hematological parameters including platelet counts, alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT), albumin, total bilirubin (TBil), prothrombin time (PT), cholesterol were routinely detected by standard assays and methods in local hospitals. Clinical, biochemical, and hematological data were recorded from each patient within 4 weeks prior to liver biopsy. Non-invasive fibrosis scores were calculated according to the following formulae: APRI = ([AST/ULN]/platelet count [×109/L]) × 100; FIB-4 = (age × AST)/(platelet count) [×109/L] × ALT1/2); and Forns’ index = 7.811 − 3.131 × LN (platelet count) + 0.781 × LN (GGT) + 3.467 × LN (age) − 0.014 × LN (cholesterol) [14–16]. The blood sample was taken at the time of liver biopsy and stored at −80 °C.

Serum HBsAg levels (rang of 20–52000 IU/ml) were quantified using the Roche Elecsys HBsAg II assay (Roche Diagnostics, Penzberg, Germany) and HBV-DNA (range 2.0 × 101–1.7 × 108 IU/ml) was measured by COBAS AmpliPrep/COBAS TagMan, Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland.

The serum concentrations of C5a and collagen IV (CO-IV) were measured using the Human Diagnostic Luminex Screening System (LXSAHM-6, R&D Systems, Inc, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Concentrations of laminin (5–900 μg/L), hyaluronic acid (range of 2–200 μg/L), procollagen type III N-terminal peptide (PIIINP) (range from 6 to 1000 μg/L) were detected using a chemiluminescent quantitative immunoassay (The source, biomedical engineering co., LTD, Beijing, China). The coefficient of variation (CV) between the duplicate wells was controlled within 10 % and R-square of the standard curve was at least 0.999.

Histology

Liver biopsy and histopathological examination were performed as previously reported [13]. All biopsies had a minimal length of 20 mm (with at least 11 portal tracts) and were scored according to Ishak system [17]. Nil/mild fibrosis was defined as F0-1, moderate fibrosis as F2, significant fibrosis as F3, severe fibrosis as F4 and cirrhosis as F ≥ 5.

Statistics

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for comparison of multiple groups. Differences of normally and non-normally distributed variables between the groups were analyzed using Student t test, Kruskal–Wallis and Mann–Whitney U tests, respectively. To assess differences in proportions, Chi-square test was used. We performed multiple ordered logistic regression analyses with Ishak fibrosis score as the dependent variable and parameters as the explanatory to compute regression equations. Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves were created for the assessment of non-invasive models for staging liver fibrosis and cirrhosis. The predictive performance expressed as areas under the ROC (AUCROCs), sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV). The classification accuracy of variables for diagnosis was validated via leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV). All data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) or proportions, and P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. SPSS 17.0 was used for data analysis.

Results

Patients characteristics

Twenty two patients were excluded because of liver biopsy length less than 20 mm and/or 11 portal tracts, and 486 cases with chronic HBV infection were analyzed finally. Basic demographic, clinical and biochemical data of patients were presented in Table 1. The mean age of cohort was 38.91 ± 10.63 years and 377 (77.6 %) were male. One hundred and eighty seven (38.5 %) patients were histologically classified as at least significant fibrosis and 31 (6.4 %) ones as cirrhosis. Parameters of age, ALT, AST, ALP, GGT, Total bilitubin, hyaluronic acid, laminin, PIIINP and CO-IV were positively, and platelet count, albumin, Lg HBVDNA, lg HBsAg were negatively associated with fibrosis stages. In the group of cirrhosis, 29 (90.3 %) patients were diagnosed as earlier fibrosis (F = 5). Compared with severe fibrosis, earlier fibrosis did not showed lower platelet count and albumin significantly.

Table 1.

Patients characteristics

| Parameters | F0-1 (n = 148, 30.5 %) | F2 (n = 151, 31.1 %) | F3 (n = 90, 18.5 %) | F4 (n = 66, 13.6 %) | F5–6 (n = 31, 6.4 %) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (≥40 years, n) | 47 (31.8 %) | 66 (43.7 %) | 50 (55.6 %) | 35 (53.0 %) | 18 (58.1 %) | |

| Gender (male, n) | 114 (77.0 %) | 118 (78.1 %) | 65 (72.2 %) | 57 (86.4 %) | 23 (74.2 %) | |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 22.84 ± 2.48 | 23.49 ± 4.46 | 23.53 ± 2.86 | 24.24 ± 2.86 | 23.67 ± 3.43 | 0.073 |

| Platelet count (×109/L) | 192.95 ± 53.92 | 184.65 ± 55.04 | 152.84 ± 49.10 | 138.42 ± 44.56 | 131.00 ± 60.14 | <0.001 |

| ALT (U/L) | 72.27 ± 85.11 | 123.75 ± 143.19 | 119.54 ± 181.15 | 125.79 ± 210.96 | 97.49 ± 76.76 | 0.049 |

| AST (U/L) | 43.73 ± 41.05 | 74.41 ± 79.77 | 89.35 ± 131.05 | 80.51 ± 120.72 | 72.64 ± 40.58 | 0.002 |

| GGT (U/L) | 78.32 ± 25.34 | 80.21 ± 24.77 | 90.97 ± 35.48 | 94.16 ± 27.87 | 100.50 ± 43.17 | <0.001 |

| ALP (U/L) | 35.34 ± 40.21 | 54.66 ± 64.43 | 69.47 ± 63.14 | 83.30 ± 74.81 | 78.21 ± 79.99 | <0.001 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 45.47 ± 5.26 | 44.56 ± 4.53 | 43.47 ± 5.79 | 42.71 ± 6.12 | 39.12 ± 6.77 | <0.001 |

| Total bilirubin (µmol/L) | 16.48 ± 21.06 | 16.30 ± 15.49 | 17.13 ± 9.69 | 18.74 ± 9.59 | 26.54 ± 22.59 | <0.002 |

| PT (s) | 13.62 ± 11.27 | 13.35 ± 6.63 | 13.36 ± 1.53 | 13.27 ± 2.10 | 13.67 ± 1.87 | 0.999 |

| HBV DNA (log10IU/ML) | 6.85 ± 1.97 | 6.26 ± 1.80 | 6.11 ± 1.64 | 5.77 ± 1.93 | 5.97 ± 1.81 | <0.001 |

| HBsAg (log10IU/ML) | 3.98 ± 0.96 | 3.63 ± 0.82 | 3.19 ± 0.92 | 3.24 ± 0.62 | 3.34 ± 0.54 | <0.001 |

| HA (μg/L) | 107.20 ± 56.70 | 118.91 ± 57.06 | 159.62 ± 103.67 | 170.29 ± 90.46 | 218.47 ± 183.39 | <0.001 |

| LN (μg/L) | 44.87 ± 122.13 | 94.51 ± 197.49 | 173.34 ± 243.91 | 288.46 ± 393.37 | 173.00 ± 213.16 | <0.001 |

| PIIINP (μg/L) | 3.21 ± 3.74 | 4.54 ± 7.83 | 6.31 ± 16.13 | 6.34 ± 6.17 | 5.67 ± 4.01 | <0.001 |

| CO-IV (log10pg/ml) | 2.86 ± 0.16 | 2.90 ± 0.23 | 3.02 ± 0.22 | 3.06 ± 0.25 | 3.08 ± 0.21 | <0.001 |

F fibrosis stage, BMI body mass index, ALT alanine transaminase, AST aspartate transaminase, ALP alkaline phosphatase, GGT gamma-glutamyltransferase, PT prothrombin time, HBV hepatitis B virus, HBsAg HBV surface antigen, HA hyaluronic acid, LN laminin, PIIINP procollagen III N-terminal peptide, CO-IV collagen IV

C5a as predictor for fibrosis and earlier cirrhosis

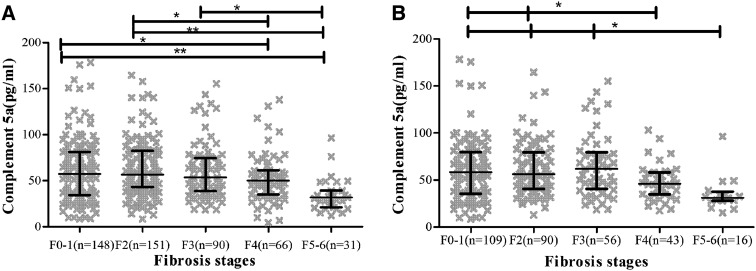

In patients with nil/mild fibrosis, C5a was median 67.83(SD 64.17); in moderate fibrosis stage, 73.97 (SD 74.56); in significant fibrosis stage, 62.23 (SD 41.45); in severe fibrosis stage, 51.85 (SD 27.30); in cirrhotic stage, 34.66 (SD 17.89); P < 0.001. C5a levels significantly decreased in patients with severe fibrosis and cirrhosis. Figure 1 showed C5a levels throughout different fibrosis stages. In patients with ALT less than 2 times of upper limit (ULN), C5a levels were also negatively associated with liver fibrosis stages and significantly declined in patients with severe fibrosis and cirrhosis.

Fig. 1.

Association between complement 5a concentration and liver fibrosis. Dotplots for complement 5a according to fibrosis stage showing mean values and interquartile ranges (IQRs). a Complement 5a in total patients; b complement 5a in patients with ALT ≤ 2 × ULN. P < 0.001 for all fibrosis stags. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05

Development of C5a -based scores for assessing significant fibrosis and earlier cirrhosis

We then performed multiple ordered logistic regression analyses with Ishak fibrosis score as the dependent variable and all possible parameters above as the explanatory, and used the coefficients (β) from the regression equations to compute and examine all possible predictive models. The presence of significant fibrosis (F ≥ 3) was usually used as a determinant for initiating antiviral therapy, and cirrhosis (F ≥ 5) indicated the need for screening HCC. AS the predictive models including C5a, AST, Laminin, Co-IV, Platelet count, Albumin, HBsAg had the highest AUROCs for significant fibrosis and cirrhosis, we choose the two models as the novel C5a-based fibrosis scores in patients chronically infected with HBV. The coefficients and the odds with 95 % confidence interval of such selected parameters from the two regression equation for predicting significant fibrosis and cirrhosis were shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Multiple ordered logistic regression analysis with Ishak fibrosis stages as the dependent variable in patients with chronic hepatitis B

| Variable | Fib-model | Cirrh-model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | OR (95 % CI) | P | β | OR (95 % CI) | P | |

| C5a | −0.013 | 0.987 (0.976, 0.999) | 0.029 | −0.045 | 0.956 (0.932, 0.980) | <0.001 |

| logCO-IV | 1.832 | 6.249 (0.749, 52.159) | 0.091 | 3.686 | 39.900 (2.320, 686.252) | 0.011 |

| logHBsAg | −0.948 | 0.388 (0.243, 0.617) | <0.001 | −0.582 | 0.559 (0.286, 1.091) | 0.088 |

| Albumin | −0.046 | 0.955 (0.884, 1.031) | 0.234 | −0.198 | 0.820 (0.734, 0.917) | <0.001 |

| Platelet count | −0.017 | 0.984 (0.976, 0.991) | <0.001 | −0.016 | 0.984 (0.975, 0.994) | 0.002 |

| AST | 0.006 | 1.006 (0.999, 1.013) | 0.090 | 0.003 | 1.003 (0.994, 1.013) | 0.463 |

| LN | 0.004 | 1.004 (1.001, 1.007) | 0.012 | 0.001 | 1.001 (0.997, 1.004) | 0.699 |

OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, C5a complement 5a, CO-IV collagen IV, HBsAg HBV surface antigen, AST aspartate transaminase, LN laminin

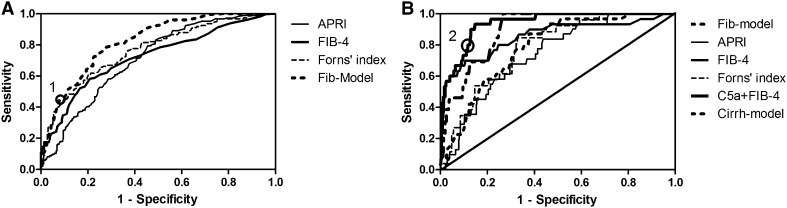

Diagnostic performance of C5a based scores, in comparison to APRI, FIB-4 and Forns’ index

Table 3 showed the diagnostic performance of non-invasive models predicting liver fibrosis. Fib-model was performing best in our group to differentiate from significant fibrosis, with an AUROC of 0.82 (95 % CI 0.78, 0.86), in comparison to existed models APRI, FIB-4 and Forns’ index with AUROCs of 0.71 (95 % CI 0.66, 0.76), 0.72 (95 % CI 0.67, 0.77), 0.77 (95 % CI 0.72, 0.81), respectively. When C5a was combined with APRI, FIB-4 and Forns’ index for assessment of significant fibrosis, AUROCs were not enhanced significantly. We identified cutoff value for Fib-model for the presence or absence of significant fibrosis, based on the ROC-curve (Fig. 2a). The cutoff for significant fibrosis at Fib-model was 0.67 (Marked 1 on Fig. 2a), with a sensitivity of 44.1 %, specificity of 92.3 %, PPV of 82.0 %, NPV of 76.8 %.

Table 3.

Areas under receiver operating characteristics (AUROCs) of non-invasive models for liver fibrosis

| Models | AUROC (95 % CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| F0-2 VS F3-6 | F0-3 VS F4-6 | F0-4 VS F5-6 | |

| APRI | 0.71 (0.66, 0.76) | 0.70 (0.65, 0.77) | 0.74 (0.67, 0.82) |

| FIB4 | 0.72 (0.67, 0.77) | 0.72 (0.65, 0.78) | 0.85 (0.77, 0.94) |

| Forns’ index | 0.77 (0.72, 0.81) | 0.77 (0.71, 0.82) | 0.78 (0.71, 0.86) |

| Fib-model | 0.82 (0.78, 0.86) | 0.82 (0.78, 0.86) | 0.79 (0.72, 0.85) |

| Cirrh-model | 0.78 (0.74, 0.83) | 0.80 (0.75, 0.85) | 0.85 (0.80, 0.91) |

| C5a + APRI | 0.72 (0.65, 0.79) | 0.74 (0.69, 0.79) | 0.81 (0.75, 0.88) |

| C5a + FIB4 | 0.74 (0.69, 0.78) | 0.73 (0.67, 0.79) | 0.94 (0.90, 0.97) |

| C5a + Forns’ index | 0.78 (0.734, 0.826) | 0.79 (0.75, 0.84) | 0.82 (0.76, 0.88) |

CI confidence interval, C5a complement 5a

Fig. 2.

Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) analysis showing the predictive value of non-invasive models for significant fibrosis and cirrhosis. a Area under the ROC curves (AUC) for Fibmodel, ARPI, FIB-4, and Forns’ index in the diagnosis of significant fibrosis (F ≥ 3): AUC Fibmodel = 0.82 (0.78, 0.86), APRI = 0.71 (0.66, 0.76), FIB-4 = 0.72 (0.67, 0.77), Forns’ index = 0.77 (0.72, 0.81). (Marker 1: cut off at 0.67). b Area under the ROC curves (AUC) for Fib-model, ARPI, FIB-4, Forns’ index and C5a + FIB-4 in the diagnosis of cirrhosis (F ≥ 5): AUC Fib-model = 0.79 (0.72, 0.85), APRI = 0.74 (0.67, 0.82), FIB-4 = 0.85 (0.77, 0.94), Forns’ index = 0.78 (0.71, 0.86), C5a + FIB-4 = 0.94 (0.90, 0.97).(Marker 2: cut off at −2.625)

For evaluation of cirrhosis, C5a + FIB-4 performed best with an AUROC of 0.94 (95 % CI 0.90, 0.97). FIB-4 and Cirrh-model with AUROCs of 0.85 (95 % CI 0.77, 0.94) and 0.85 (95 % CI 0.80, 0.91) were performing as the second best (Fig. 2b). The cutoff value of C5a + FIB-4 for cirrhosis was −2.625 (marked 2 on Fig. 2b), with a sensitivity of 80 %, a specificity of 88.2 %, a PPV of 85.8 % and a NPV of 82.9 %. With C5a + FIB-4, we correctly diagnosed 83.8 % of the patients with cirrhosis.

To validate these non-invasive models for predicting significant fibrosis and cirrhosis, LOOCV was performed. For significant fibrosis, LOOCV showed that 73.3 % cross-validation grouped cases were correctly classified by Fib-model and 64.8, 70.4, and 67.1 % classified by APRI, FIB-4 and Forns’ index (Supplemental Table S1). LOOCV also showed that C5a + FIB-4 could correctly classified 89.3 % of cases, and Cirrh-model, APRI,FIB-4 and Forns’ index just showed 71.4, 78.4, 82.6 and 75.1 % correct classification (Supplemental Table S1).

Discussion

Increasing evidence indicated that C5a participated in the pathogenesis of liver disorders, including liver injury, repair, and fibro-genesis. Complement 5, shown earlier to be correlated with liver fibrosis in mice, was found to be elevated in MTX-exposed livers [18]. C5a also could act as a growth factor in regenerating rat hepatoyes under inflammatory conditions [19]. C5-deficient mice showed impairment of liver regeneration and persistent parenchymal necrosis after exposure to CCL4 and reconstitution of C5-deficient mice with C5a significantly restored hepatocyte regeneration in a course of 6–7 days [20]. The above observations highlight C5a as one among essential factors that mediate liver regeneration and that it probably exerted its function in an early stage during this process. In this study including 486 patients, serum concentration of C5a declined significantly in severe fibrosis and earlier cirrhosis stage, which was similar to the change of another complement C4a in liver fibrogenesis. C4a was primarily expressed in liver and could induce in response to acute inflammations or tissue injury [21]. In patients with chronic hepatitis C, C4a and C3 were found to decrease in advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis [22–25]. Additionally, 90 % of complement was synthesized by liver, the significant decreasing of C5a may result from the dysfunction of hepatocyte in severely fibrotic and cirrhotic liver.

Detection of significant fibrosis (Ishak, F ≥ 3) and cirrhosis (Ishak, F ≥ 5) were the most important clinically relevant endpoints in patients with chronic hepatitis B. A diagnosis of significant fibrosis indicated that patients should receive antiviral treatment [26, 27]. However, throughout the articles, serum biomarkers for non-invasive assessment of liver fibrosis were better for detecting cirrhosis than significant fibrosis. Serum biomarkers and TE showed to have equivalent performance for detecting significant fibrosis [28–30]. The most widely validated serum biomarkers in chronic hepatitis B patients were APRI, FIB-4. A meta-analysis for APRI in 1798 HBV patients found mean AUROC values of 0.79 for significant fibrosis. In this study,the performance of C5a based model fib-model was superior to APRI, FIB-4 and Forns’ index for predicting significant fibrosis.

Once diagnosis of cirrhosis has been established, AASLD and EASL guidelines recommended that patients should be monitored for complications related to portal hypertension and regularly screened for HCC [26, 27]. In fact, it is more important to detect earlier cirrhosis than decompensated cirrhosis, which was not easily be found only according to hematologic, biochemical tests or abdominal ultrasound. In this study, decompensated cirrhosis was one of the exclusions, earlier fibrosis (F = 5) diagnosed by histology in 28 (90.3 %) patients in the group of cirrhosis. The concentration of C5a declined in earlier cirrhosis and helped the diagnosis. AUROC of combination of C5a and FIB-4 for predicting earlier cirrhosis was 0.94, significantly superior to APRI, FIB-4 and Forn’s index.

Although transient elastography (TE) more accurately detected cirrhosis (AUROC values 0.88–0.99), it is usually only available in specialized centres and its applicability is not as good as that of serum biomarkers [3, 31]. Besides, TE values have been reported overestimation due to ALT flares [3]. Another limitation for using TE seems the difficulty to obtain from obese patients, and patients with ascites [32].

One clear limitation of this study was the small sample size of cirrhotic patients, the value of C5a for diagnosing earlier cirrhosis should be validated in a large cohort in future study. The second limitation was that a substantial overlap of C5a concentration was observed between adjacent stages of the fibrosis, especially for lower fibrosis stages. In fact, other excellent biomarkers reported in previous study also failed to avoid overlap [31, 33]. Although lack of validation group was another limitation of this study, LOOCV which has the advantages of producing model estimates more easily and with less bias in smaller samples has been used to cover the shortage [34]. Additionally,this study is clinical research. The basic research of the relationship between Angptl2 and liver fibrosis is currently in progress.

In conclusion, C5a declined significantly in severe fibrotic and early cirrhotic stages in patients with chronic HBV infection. Combination of C5a and FIB-4 offered an easy possibility to diagnose early cirrhosis and its performance was superior to existing scores APRI, FIB-4 and Forns’ index.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Members of China HepB Related Fibrosis Assessment Research Group has been described previously [13]. China HepB Related Fibrosis Assessment Research Group: We thank Professor Xin Xu (Nanfang Medical University, China) for his guidance with the statistics.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

None.

Funding

This study was supported by China Mega-Project for Infectious Diseases (Grant Numbers 2013ZX10002005, 2012ZX10002006, 2013ZX10002004, 2012ZX10005005), Project of Beijing Science and Technology Committee (Grant Number D121100003912002).

Footnotes

Y. Deng and H. Zhao contributed equally to this study.

Contributor Information

Yongqiong Deng, Email: dyq831204@vip.126.com.

Hong Zhao, Email: 987047361@126.com.

Jiyuan Zhou, Email: 174435465@qq.com.

Linlin Yan, Email: ouyangyl1981@163.com.

Guiqiang Wang, Phone: 861083572764, Email: john131212@126.com.

References

- 1.Locarnini S, Hatzakis A, Chen DS, Lok A. Strategies to control hepatitis B: public policy, epidemiology, vaccine and drugs. J Hepatol. 2015;62:76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rockey DC, Caldwell SH, Goodman ZD, Nelson RC, Smith AD. Liver biopsy. Hepatology. 2009;49:1017–1044. doi: 10.1002/hep.22742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.European Association for Study of Liver, Association Latinoamericana para el Estudio del Higado EASL-ALEH clinical practice guidelines: non-invasive tests for evaluation of liver disease severity and prognosis. J Hepatol. 2015;63:237–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castera Laurent. Noninvasive methods to assess liver disease in patients with hepatitis B or C. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1293–1302. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poynard T, Munteanu M, Deckmyn O, Ngo Y, Drane F, Messous D, Castille JM, et al. Applicability and precautions of use of liver injury biomarker FibroTest. A reappraisal at 7 years of age. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-11-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imbert-Bismut F, Messous D, Thibaut V, Myers RB, Piton A, Thabut D, Devers L, et al. Intra-laboratory analytical variability of biochemical markers of fibrosis (Fibrotest) and activity (Actitest) and reference ranges in healthy blood donors. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2004;42:323–333. doi: 10.1515/cclm.2004.42.6.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cales P, Veillon P, Konate A, Mathieu E, Ternisien C, Chevailler A, Godon A, et al. Reproducibility of blood tests of liver fibrosis in clinical practice. Clin Biochem. 2008;41:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lambris JD, Sahu A, Wetsel R. The chemistry and biology of C3, C4, and C5. In: Volanakis JE, Frank M, editors. The human complement system in health and disease. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1998. pp. 83–118. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monk PN, Scola AM, Madala P, Fairlie DP. Function, structure and therapeutic potential of complement C5a receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;152:429–448. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schlaf G, Schmitz M, Heine I, Demberg T, Schieferdecker HL, Götze O. Upregulation of fibronectin but not of entactin, collagen IV and smooth muscle actin by anaphylatoxin C5a in rat hepatic stellate cells. Histol Histopathol. 2004;19:1165–1174. doi: 10.14670/HH-19.1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruonan X, Fang L, Jin H, Lei J, Jiyuan Z, Junliang F, Honghong L, et al. Complement 5a stimulates hepatic stellate cells in vitro, and is increased in the plasma of patients with chronic hepatitis B. Immunology. 2013;138:228–234. doi: 10.1111/imm.12024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hillebrandt S, Wasmuth HE, Weiskirchen R, Hellerbrand C, Keppeler H, Werth A, Schirin-Sokhan R, et al. Complement factor 5 is a quantitative trait gene that modifies liver fibrogenesis in mice and humans. Nat Genet. 2005;37:835–843. doi: 10.1038/ng1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deng YQ, Zhao H, Ma AL, Zhou JY, Xie SB, Zhang XQ, Zhang DZ, et al. Selected cytokines serve as potential biomarkers for predicting liver inflammation and fibrosis in chronic hepatitis B patients with normal to mildly elevated aminotransferases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e2003. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wai CT, Greenson JK, Fontana RJ, Kalbfleisch JD, Marrero JA, Conjeevaram HS, et al. A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:518–526. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vallet-Pichard A, Mallet V, Nalpas B, Verkarre V, Nalpas A, Dhalluin-Venier V, et al. FIB-4: an inexpensive and accurate marker of fibrosis in HCV infection. Comparison with liver biopsy and fibrotest. Hepatology. 2007;46:32–36. doi: 10.1002/hep.21669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forns X, Ampurdanès S, Llovet JM, Aponte J, Quintó L, Martínez-Bauer E, et al. Identification of chronic hepatitis C patients without hepatic fibrosis by a simple predictive model. Hepatology. 2002;36:986–992. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishak K, Baptista A, Bianchi L, Callea F, De Groote J, Gudat F, et al. Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1995;22:696–699. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(95)80226-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belinsky GS, Parke AL, Huang Q, Blanchard K, Jayadev S, Stoll R, Rothe M, et al. The contribution of methotrexate exposure and host factors on transcriptional variance in human liver. Toxicol Sci. 2007;97:582–594. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daveau M, Benard M, Scotte M, Schouft MT, Hiron M, Francois A, Salier JP, et al. Expression of a functional C5a receptor in regenerating hepatocytes and its involvement in a proliferative signaling pathway in rat. J Immunol. 2004;173:3418–3424. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mastellos D, Papadimitriou JC, Franchini S, Tsonis PA, Lambris JD. A novel role of complement: mice deficient in the fifth component of complement (C5) exhibit impaired liver regeneration. J Immunol. 2001;166:2479–2486. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galibert MD, Boucontet L, Goding CR, Meo T. Recognition of the E-C4 element from the C4 complement gene promoter by the upstream stimulatory factor-1 transcription factor. J Immunol. 1997;159:6176–6183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.White IR, Patel K, Symonds WT, Dev A, Griffin P, Tsokanas N, Skehel M, Liu C, Zekry A, Cutler P, Gattu M, Rockey DC, Berrey MM, McHutchison JG. Serum proteomic analysis focused on fibrosis in patients with hepatitis C virus infection. J Transl Med. 2007;5:33. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-5-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Behairy BE, El-Mashad GM, Abd-Elghany RS, Ghoneim EM, Sira MM. Serum complement C4a and its relation to liver fibrosis in children with chronic hepatitis C. World J Hepatol. 2013;5:445–451. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v5.i8.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gangadharan B, Antrobus R, Chittenden D, Rossa J, Bapat M, Klenerman P, Barnes E, et al. New approaches for biomarker discovery: the search for liver fibrosis markers in hepatitis C patients. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:2643–2650. doi: 10.1021/pr101077c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang H, Sun F, Owen DM, Li W, Chen Y, et al. Hepatitis C virus production by human hepatocytes dependent on assembly and secretion of very low-density lipoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:5848–5853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700760104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarin SK, Kumar M, Lau GK, Abbas Z, Chan HL, Chen CJ, et al. Asian-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatitis B: a 2015 update. Hepatol Int. 2016;10:1–98. doi: 10.1007/s12072-015-9675-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Terrault NA, Bzowej NH, Chang KM, Hwang JP, Jonas MM, Murad MH. AASLD guidelines for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2016;63:261–283. doi: 10.1002/hep.28156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Degos F, Perez P, Roche B, Mahmoudi A, Asselineau J, Voitot H, Bedossa P, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of FibroScan and comparison to liver fibrosis biomarkers in chronic viral hepatitis: a multicenter prospective study (the FIBROSTIC study) J Hepatol. 2010;53:1013–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zarski JP, Sturm N, Guechot J, Paris A, Zafrani ES, Asselah T, Boisson RC, et al. Comparison of nine blood tests and transient elastography for liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C: the ANRS HCEP-23 study. J Hepatol. 2012;56:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Castera L, Vergniol J, Foucher J, Le Bail B, Chanteloup E, Haaser M, Darriet M, et al. Prospective comparison of transient elastography, Fibrotest, APRI, and liver biopsy for the assessment of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:343–350. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maieron A, Salzl P, Peck-Radosavljevic M, Trauner M, Hametner S, Schöfl R, Ferenci P, et al. Von Willebrand factor as a new marker for non-invasive Assessment of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:331–338. doi: 10.1111/apt.12564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sandrin L, Fourquet B, Hasquenoph JM, Yon S, Fournier C, Mal F, Christidis C, et al. Transient elastography: a new noninvasive method for assessment of hepatic fibrosis. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2003;29:1705–1713. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kazankov K, Barrera F, Møller HJ, Bibby BM, Vilstrup H, George J, Grønbaek H. Soluble CD163, a macrophage activation marker, is independently associated with fibrosis in patients with chronic viral hepatitis B and C. Hepatology. 2014;60:521–530. doi: 10.1002/hep.27129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Molinaro AM, Simon R, Pfeiffer RM. Prediction error estimation: a comparison of resampling methods. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3301–3307. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.