Abstract

Blindness afflicts ~39 million people worldwide. Retinal ganglion cells are unable to regenerate, making this condition irreversible in many cases. Whole-eye transplantation (WET) provides the opportunity to replace diseased retinal ganglion cells, as well as the entire optical system and surrounding facial tissue, if necessary. Recent success in face transplantation demonstrates that this may be a promising treatment for what has been to this time an incurable condition. An animal model for WET must be established to further enhance our knowledge of nerve regeneration, immunosuppression, and technical aspects of surgery. A systematic review of the literature was performed to evaluate studies describing animal models for WET. Only articles in which the eye was completely enucleated and reimplanted were included. Study methods and results were compared. In the majority of published literature, WET can result in recovery of vision in cold-blooded vertebrates. There are a few instances in which mammalian WET models demonstrate survival of the transplanted tissue following neurovascular anastomosis and the ability to maintain brief electroretinogram activity in the new host. In this study we review in cold-blooded vertebrates and mammalian animal models for WET and discuss prospects for future research for translation to human eye transplantation.

Introduction

Blindness afflicts 39 million people worldwide.1 Loss of vision causes significant disability as well as a deleterious impact on quality of life and independence. There is currently no treatment available for loss of vision due to optic nerve atrophy or retinal ganglion cell loss, which can be caused by end-stage glaucoma, traumatic optic atrophy,2 and other diseases. Whole-eye transplantation (WET) may be a viable treatment option. The Advisory Council for the National Eye Institute called for limited and thoughtful laboratory effort in the area of eye transplantation in 1977.3 Successful face and partial face transplantation have become more common and have proven to be safer and more effective than initially anticipated,4 which may help pave the way for successful WET.

When blindness is caused by trauma, it is often accompanied by severe facial disfigurement. Fifty-eight percent of US wartime ocular injuries have concomitant severe facial injury, thus there is a population that would potentially benefit from combined face and WET.4 With continued improvements in nerve regeneration and immunosuppression, transplantation has become an increasingly viable option for treatment of otherwise extremely complex and debilitating disease processes.

Materials and methods

A review was completed of PubMed database using the search terms 'eye transplantation', 'animal model transplantation', 'optic nerve regeneration', 'circulatory revascularization of the eye', and 'face transplantation'. Abstracts were reviewed to identify articles pertaining to eye transplantation models. Additional references were obtained by using commercial internet search engines and looking through the bibliographies of included papers. Abstracts were scanned and if the manuscript potentially met inclusion criteria the complete article was reviewed. Inclusion criteria necessitated that the full article be available in the English language and the eye must have been completely enucleated and reimplanted.

Results

Cold-blooded vertebrate models

One of the first successful models for eye transplantation was the salamander. In 1930, Stone5 exchanged the right eye of 41 pairs of larvae of Amblystoma punctatum and A. tigrinum. He tested vision in the transplanted eyes in three of the pairs by removing the contralateral normal eye and observing if the animals would respond to visual cues. All six of the animals tested demonstrated functional return of vision in the transplanted eye.5 Similarly, Stone and Cole6 investigated 104 young and old adult A. punctum (78 reimplanted in the same animal and 26 transplanted into a new host). Return of vision by behavioral response was demonstrated in five reimplanted eyes and four transplanted eyes.6 In 1937, Stone7 continued his experiments with both transplantation and replantation of 186 A. punctum larvae. Twenty-six of the transplanted and nine of the replanted animals were tested for return of vision via behavioral response. Thirty-one of the 35 salamanders tested had successful visual response to stimuli.7 Similar success was demonstrated in adult Triturus viridescens. Following transplantation of 59 eyes and enucleation followed by reimplantation of 33 animals, 13 were tested for return of vision using behavioral response to visual cues. Six of the nine animals with reimplanted globes tested for return of vision demonstrated a positive behavioral response, the number of animals with return of vision following transplantation was not recorded.8 Interspecies eye transplantation was performed between A. punctatum and T. viridescens. Thirty-four Amblystoma hosts with Triturus eyes and 46 Triturus hosts with Amblystoma eyes were investigated. All Triturus eyes on Amblystoma hosts degenerated, however Amblystoma eyes on Triturus hosts recovered and eight demonstrated return of vision as verified by snapping at a red rubber moved outside their cage.9 Differently, exchanging eyes between Typhlotriton spelaeus and A. punctatum species resulted in return of vision in both species. Thirteen pairs of animals had eyes exchanged across species. Vision was demonstrated in five of 10 Amblystoma and four of seven Typhlotriton transplantations.10 Reimplantation of nine T. spelaeus and one T. nereus resulted in return in vision in one of one T. nereus and seven of nine T. Spelaeus.11 Ambystoma larvae adapt their skin coloration for camouflage. Bilateral enucleation immediately and irreversibly cancels this ability. Pietsch et al12 enucleated 22 Amblystoma larvae and then proceeded with eye transplantation. Eighteen of 22 animals recovered skin camouflage reaction to their environment demonstrating successful return of vision.12

Frogs and toads have been used successfully in eye transplantation studies. In 1924, Koppanyi and Baker13 excised the eyes of European (Bombinator) toads and replanted them into the same eye socket. Skin color adaptation, which is visually stimulated, returned after 8 weeks thus indicating the return of vision.13 Between 1924 and 1928, Keeler replanted 60 eyes of Rana pipiens. He, however, found no evidence for return of vision in all cases. Differently, Sperry14 transplanted eyes to the contralateral side in 30 anurans tadpoles and 21 full-grown adult urodele amphibians. He noted a return in vision in two of the 30 tadpoles as determined by jumping at a lure after they had undergone metamorphosis into frogs. Twelve of the 21 urodele regained vision.14 Adding a level of complexity, Sedohara et al,15 successfully induced the formation of eyes from the African frog (Xenopus) early gastrulae in vitro and transplanted these organs into Xenopus tadpoles. Three of the 15 tadpoles retained the eyes after metamorphosis and these animals were noted to adapt the color of their skin based on background light intensity, an adaptation that requires visual stimuli, suggesting the return of vision.15 Xenopus were not only able to demonstrate a return of vision after transplantation of eyes developed in vitro, but are able to establish visual pathways after ectopic eye transplantation to the tails of tadpoles. Six of 31 animals with ectopic eye transplantation demonstrated light-mediated learning and the ectopic eyes were shown to develop innervation pathways to the trunk and spine of the host.16 All cold-blooded vertebrate eye transplantation studies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Cold-blooded invertebrate eye transplantation animal models.

| Article | First author | Ref. | Model | Number of eyes transplanted | Number of eyes replanted | Vision analysis method | Number of eyes tested/return of vision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heteroplastic transplantation of the eyes between the larvae of two species of Amblystoma | Stone | 5 | Salamander, larvae | 82 | 0 | Behavioral response | Transplanted: 6/6 |

| Grafted eyes of young and old adult salamanders (Amblystoma punctum) showing return of vision | Stone | 6 | Salamander, adults (1–3 years) | 26 | 78 | Behavioral response | Transplanted: 4/26 Reimplanted: 5/78 |

| Reimplantation and transplantation of larval eyes in the salamander A. punctum | Stone | 7 | Salamander, larvae | 126 | 59 | Behavioral response | Transplanted: 25/26 Reimplanted: 6/9 |

| Reimplantation and transplantation of adult salamander (Triturus viridescens) with return of vision | Stone | 8 | Salamander, adult | 59 | 33 | Behavior response | Reimplanted:6/9 Transplanted: NA/4 |

| Return of vision in eyes exchanged between adult salamanders of different species | Stone | 9 | Salamander, adult, across species | 80 | 0 | Behavioral response | Transplanted: 8/80 |

| Return of vision in larval eyes exchanged between A. punctum and the cave salamander, Typhlotriton spelaeus | Stone | 10,11 | Salamander, larvae, across species | 26 | 0 | Behavioral response | Transplanted: 9/17 |

| Return of vision in transplanted larval eyes of cave salamanders | Stone | 10,11 | Salamander, larvae | 0 | 10 | Behavioral response | Reimplanted: 8/10 |

| Transplanted eyes of foreign donors can reinstate the optically activated skin camouflage reactions in bilaterally enucleated salamanders (Ambystoma) | Pietsch | 12 | Salamander, larvae | 22 | 0 | Skin camouflage | Transplanted: 18/22 |

| Further studies on eye transplantation in the spotted rat | Koppanyi | 13 | Toad, adult | 0 | NA | Skin camouflage | NA |

| The functional capacity of transplanted adult frog eyes | Keeler | 28 | Frog, adult | 0 | 60 | Action current | Reimplanted: 0/60 |

| Restoration of vision after crossing of optic nerves and after contralateral transplantation of eye | Sperry | 14 | Frog, adult | 0 | 51 | Behavioral response | Reimplanted: 12/21 (adult) 2/30 (tadpoles) |

| In vitro induction and transplantation of eye during early Xenopus development | Sedohara | 15 | Frog, tadpole | 15 (eyes developed in vitro) | 0 | Skin camouflage | Implanted: 3/15 |

| Ectopic eyes outside the head in Xenopus tadpoles provide sensory data for light-mediated learning | Blackiston | 16 | Frog, tadpole | 31 (ectopic) | 0 | Behavioral response | Tranplanted: 6/31 |

Abbreviation: NA, not available. Information not recorded in manuscript referenced.

Mammalian models

Mammals provide the closest animal model for human eye transplantation. Successful re-establishment of perfusion and in some cases electroretinogram activity have been demonstrated, however full return of vision in a mammalian model has proved difficult. Mammalian animal models for eye transplantation are summarized in Table 2. In 1886, May17 performed whole-eye replantation and transplantation in 24 rabbits. None of the animals regained vision and 18 of the 24 eyes were lost. The author did not have the technical innovation to anastomose blood vessels and believed the survival of the eye was dependent on the security of the post-operative bandage and length of time it remained in place.17 In 1924, Koppanyi and Baker13 extended their experiments from cold-blooded animals to the rat. They enucleated and replanted the eyes of 25 animals and noted the return of the corneal reflex in two animals.13 No microvascular anastomoses or optic nerve coaptations were performed in these animals. Freed and Wyatt18 utilized the Sprague–Dawley rat in examining the ability of fetal eyes transplanted into the brains of blinded adults to develop light sensitivity. Twelve rat eyes were examined histologically and in two cases organized retinae were observed. Evoked responses to light flashes were recorded in three of nine, suggesting the development of sensitivity to light.18 Larger animals such as canines, ovine, and swine have been used to demonstrate revascularization after eye transplantation to various sites. Twenty-five canine eyes were enucleated and the ciliary artery and internal ophthalmic vein anastomosed to the rat femoral artery and vein. All eyes demonstrated active circulation via microscopic appearance of the vessels and active bleeding from the cut surfaces of the insertions of the extraocular muscles. In three cases sodium fluorescein was injected into the rat circulation and was subsequently noted to fill the major retinal arteries and veins in two of these animals, the third angiogram was not technically satisfactory for interpretation.19 Sher20 was the first to successfully demonstrate reperfusion following autotransplantation of mammalian eyes in an ovine model. Twenty sheep had eyes transplanted to the contralateral orbit. The ciliary and internal ophthalmic arteries and six venous outflow channels (the two superior and two inferior cortex veins, and the ciliary and internal ophthalmic veins) were anastomosed. The re-establishment of active circulation was noted by microscopic appearance of the vessels on the optic nerve and sclera, as well as scleral injection and bleeding from the cut edges of the insertions of the extraocular muscles. Five animals underwent fluorescein angiography and all cases demonstrated sequential filling of the major retinal arteries and veins. Sher20 did not evaluate retinal function in these experiments. Shi et al21 exenterated swine eyes and anastomosed the ophthalmic artery to the carotid artery. Slit lamp examination revealed no abnormalities in the exenterated eyes. Electroretinogram and optic nerve responses were partially recovered and remained stable for 3 h at which point the experiment was terminated. Restoration of reperfusion was confirmed with histology by the presence of FITC lectin-stained retinal vessels imaged with confocal microscopy.21

Table 2. Mammalian eye transplantation animal models.

| Article | First author | Ref. | Model | Number of eyes transplanted | Analysis method and outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enucleation with transplantation and reimplantation of eyes | May | 17 | Rabbit | 24 transplanted | 0 of 24 regained vision 6 of 24 eyes survived |

| Transplantation of eyes to the adult rat brain: histological findings and light-evoked potential response | Freed | 18 | Rat | Fetal eyes transplanted onto adult brains | Light-evoked potential in 3 of 9 retinal cells on histology 2 of 12 |

| Further studies on eye transplantation in the spotted rat | Koppanyi | 13 | Rat | 25 reimplanted | Corneal reflex 2 of 25 |

| Revascularization of isolated extracorporal canine eyes by direct microsurgical anastomosis | Sher | 19 | Canine, rat | 25 canine eyes anastomosed ectopically to rat femoral vessels | Active circulation in 25 of 25 |

| Revascularization of autotransplanted ovine eyes by microsurgical anastomosis | Sher | 20 | Sheep | 20 reimplanted on contralateral side | Active circulation in 20 of 20 |

| Restoration of electroretinogram activity in exenterated swine eyes following ophthalmic artery anastomosis | Shi | 21 | Swine | 20 reimplanted ectopically | Electroretinogram activity 20 of 20 |

Discussion

Human WET holds promise to restore vision to patients suffering from blindness. Significant research has been conducted with the aim of achieving this goal. The first mention of eye transplantation in humans occurred as early as 1885 in Revue Gènèrale d' Ophthalmologie. Dr Chibret removed the staphylomatous and buphthalmic eye of a 17-year-old girl and placed a rabbit eye into the empty conjunctival sac. The transplanted eye was then sutured in place through the patient's conjunctiva to the transplanted cornea. The transplanted organ perished by the fifteenth post-operative day.17 Later that year, Dr Terrier reported in the Sociètè de Cirurgie of Paris a similar operation in which the cornea sloughed on post-operative day three. The third recorded xenograft was described by M Rohmer and similarly, the cornea sloughed 7 days post procedure. Bradford22 reported his experience with the operation in September of that year in Boston Medical and Surgical Journal. He anastomosed the transplanted optic nerve to the remaining nerve stump of the recipient, and the extraocular muscles were sutured to the remaining subconjunctival tissue. Recorded follow-up was only 18 days at which point the eye appeared viable but did not demonstrate evidence of reestablished vision.22 Terrier attempted to repeat Bradford's22 reported success, but this operation led to demise of the transplanted organ.17 Cadaveric donor human WET was attempted in 1969 at Methodist Hospital in Houston. The cornea, lens, and iris were transplanted but failed to restore vision.23 Substantial progress is needed before human whole-eye allotransplantation with successful return of vision will be accomplished.24

Challenges to successful WET are three-fold: developing effective and benign immunosuppression, improved nerve regeneration capability, and optimizing surgical technique. An immunosuppressive protocol that hinders immune rejection with a minimal side effect profile remains elusive despite significant advances in the field. The capability of nerves to regenerate after ligation and coaptation continues to be slow, unpredictable, and incomplete. However, certain drugs, such as FK506, have neuroregenerative properties in addition to their immunosuppressive effects. Thus, it might be an ideal starting point for immunosuppressive therapy for WET. The optic nerve must regenerate and allow for the conduction of light stimuli to the appropriate visual centers of the brain, and correct interpretation of those signals, for eye transplantation to be effective. The optimal surgical technique must be developed to ensure an efficient operation with short ischemia time and high rates of success. Animal models are needed to advance our knowledge in these three areas and to progress toward the goal of successful WET in humans.

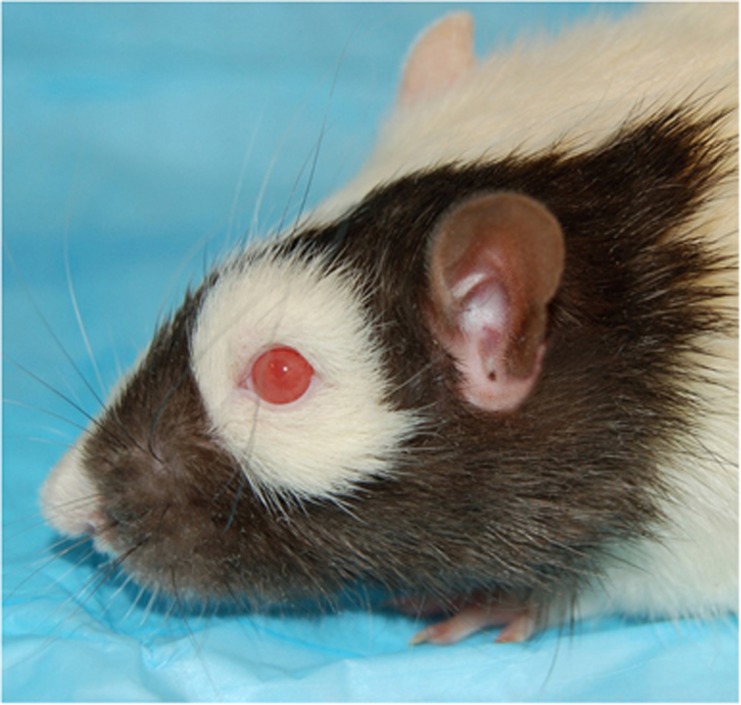

The ideal approach for advancing the future of WET would be separated into phases. Early phases of research should focus on high-throughput studies to develop and hone the transplantation technique and perform basic science research. The rat model is a good option for large volume studies and has been used successfully as a prototype for face and hemi-face transplantation. It is easily reproducible and from a technical standpoint the optic nerve and vascular anastomosis can be performed using an operating microscope. Importantly, the anatomy of the microvasculature of the optic nerve head in rats is similar to primates.25 The rat animal model has been used successfully to help develop the knowledge needed to make face and partial face transplantation a reality and will serve a similar role in the development of WET. Figure 1 demonstrates a rat hemi-face model developed by our group. Strains of rats with pigmented eyes, such as the Brown–Norway, might be better fit for studying WET once functional testing becomes the goal because the pigment protects the sensitive nocturnal retina from photopic retinopathy due to light exposure.26 Testing such as non-invasive ocular imaging, electrophysiology, and slit lamp examination can be easily performed in the rodent. In addition, behavior studies to assess function are well established in the rodent. Our group has established a viable orthotopic model for vascularized eye transplantation in the rat. This model is ideal for examining viability, functional return, and immunology in WET.27

Figure 1.

Brown–Norway rat donor with Lewis rat recipient hemifacial transplantation model previously described by Washington et al.24

Non-human primates are an ideal next step in the research after rodent studies, in addition to human cadaveric studies. Non-human primate research may have the benefit of a wider array of techniques available to test and showcase functional return. Behavioral tests, as well as electroretinography would be valuable tools in evaluating visual function and its impact on the animal. This step, along with cadaveric studies, in the pursuit of WET would be crucial in determining the surgical feasibility of the procedure as well as if the potential patient would receive any clinically important return of visual function. The road to making WET a clinical reality for those who have lost their sight is long and fraught with complex scientific hurdles. However, the required knowledge, surgical skill, technology, and medicine has advanced to the point where overcoming these difficulties may be within reach.

References

- WHO. Global Data on Visual Impairment. Available at: http://www.who.int/blindness/publications/globaldata/en/ (accessed on 2 October 2014).

- Ellenberg D, Shi J, Jain S, Chang JH, Brady S, Melhem E et al. Impediments to eye transplantation: ocular viability following optic nerve transection or enucleation. Br J Ophthalmol 2009; 93: 1134–1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scientists urged to hold firm to eye transplant goal. JAMA 1978; 240(12)1227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carty MJ, Bueno EM, Soleymani Lehmann L, Pomahac B. A position paper in support of face transplantation in the blind. Plast Reconstr Surg 2012; 130: 319–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone LS. Heteroplastic transplantation of the eyes between the larvae of two species of Amblystoma. J Exp Zool 1930; 55: 193–261. [Google Scholar]

- Stone LS, Cole HS. Grafted eyes of young and old adult salamanders (amblystoma punctatum showing return of vision. Yale J Biol Med 1943; 15: 735–755. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone L, Ussher N, Beers D. Reimplantation and transplantation of larval eyes into the salamander Amblystoma punctum. J Exp Zool 1937; 77: 13–47. [Google Scholar]

- Stone L, Zaur L. Reimplantation and transplantation of adult eyes in the salamander (triturus viridescens with return of vision. J Exp Zool 1940; 85: 243–269. [Google Scholar]

- Stone L, Ellison F. Return of vision in eyes exchanged between adult salamanders of different species. J Exp Zool 1945; 100: 217–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone LS. Return of vision in larval eyes exchanged between Amblystoma punctatum and the cave salamander, Typhlotriton spelaeus. Investig Ophthalmol 1964; 3(6): 555–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone LS. Return of vision in transplanted larval eyes of cave salamanders. J Exp Zool 1964; 156: 219–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietsch P, Schneider C. Transplanted eyes of foreign donors can reinstate the optically activated skin camouflage reactions in bilaterally enucleated salamanders (Ambystoma). Brain Behav Evol 1988; 32(6): 364–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppányi T, Baker C. Further studies on eye transplantation in the spotted rat. Am J Physiol 2014; 71: 344–348. [Google Scholar]

- Sperry R. Restoration of vision after crossing of optic nerves and after contralateral transplantation of eye. J Neurophysiol 1945; 8: 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sedohara A, Komazaki S, Asashima M. In vitro induction and transplantation of eye during early Xenopus development. Dev Growth Differ 2003; 45(5-6): 463–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackiston DJ, Levin M. Ectopic eyes outside the head in Xenopus tadpoles provide sensory data for light-mediated learning. J Exp Biol 2013; 216(Pt 6): 1031–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May C. Enucleation with transplantation and reimplantation of eyes. Med Rec 1886; 29(22): 613–621. [Google Scholar]

- Freed W, Wyatt RJ. Transplantation of eyes to the adult rat brain: histological findings and light-evoked potential response. Life Sci 1980; 27(6): 503–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher H, Cohen RJ. Revascularization of isolated extracorporeal canine eyes by direct microsurgical anastomosis. J Microsurg 1981; 1(5): 399–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher H. Revascularization of autotransplanted ovine eyes by microsurgical anastomosis. J Microsurg 1981; 2(4): 269–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Ellenberg D, Kim JY, Qian H, Ripps H, Jain S et al. Restoration of electroretinogram activity in exenterated swine eyes following ophthalmic artery anastomosis. Restor Neurol Neurosci 2009; 27(4): 351–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford H. A case of enucleation with replacement of the human globe by that of a rabbit. Bost Med Surg J 1885; 113(12): 269–270. [Google Scholar]

- O'Brian S. Science and Technology Milestones in 1969. Available at: seniorliving.about.com/od/boomernostalgia/tp/1969-milestones-science.htm (accessed on 3 September 2016).

- Washington KM, Solari MG, Sacks JM, Horibe EK, Unadkat JV, Carvell GE et al. A model for functional recovery and cortical reintegration after hemifacial composite tissue allotransplantation. Plast Reconstr Surg 2009; 123(2 Suppl): 26S–33S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison JC, Johnson EC, Cepurna WO, Funk RHW. Microvasculature of the rat optic nerve head. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1999; 40(8): 1702–1709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council (US) Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. National Academies Press (US): Washington (DC), 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiaki K, Bo W, Maxine RM, Hongkun W, Yolandi van der M, Leon CH et al. Evaluation of viability, structural integrity and functional outcome after whole eye transplantation. Plastic Reconstr Surg 2015; 135: 82. [Google Scholar]

- Keeler C. The functional capacity of transplanted adult frog eyes. J Exp Zool 1929; 54(3): 461–472. [Google Scholar]