Abstract

Objectives

This review aims to understand what elements of psychosocial interventions are associated with improved outcomes for people with dementia to inform implementation in care homes.

Design

A systematic review of qualitative and quantitative intervention studies was undertaken.

Eligibility criteria for included studies

We included primary research studies evaluating psychosocial interventions that trained care home staff to deliver a specific intervention or that sought to change how staff delivered care to residents with dementia and reported staff and resident qualitative or quantitative outcomes.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE, PsychINFO and EMBASE electronic databases and hand-searched references up to May 2016. Quality of included papers was rated independently by 2 authors, using operationalised checklists derived from standard criteria. We discussed discrepancies and reached consensus. We conducted a narrative synthesis of quantitative and a thematic synthesis of qualitative findings to find what was effective immediately and in sustaining change.

Results

We identified 49 papers fulfilling predetermined criteria. We found a lack of higher quality quantitative evidence that effects could be sustained after psychosocial interventions finished with no evidence that interventions continued to work after 6 months. Qualitative findings suggest that staff valued interventions focusing on getting to know, understand and connect with residents with dementia. Successful elements of interventions included interactive training, post-training support, aiming to train most staff, retaining written materials afterwards and building interventions into routine care.

Conclusions

Psychosocial interventions can improve outcomes for staff and residents with dementia in care homes; however, many trial results are limited. Synthesis of qualitative findings highlight core components of interventions that staff value and feel improve care. These findings provide useful evidence to inform the development of sustainable, effective psychosocial interventions in care homes.

Trial registration number

CRD42015017621.

Keywords: QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to systematically review qualitative and quantitative studies which consider the impact of psychosocial interventions on care home staff and residents with dementia.

By focusing on psychosocial interventions delivered either by training care staff to change their practices or interventions directly delivered by care home staff, our review informs development of sustainable interventions in ‘real-world’ care home settings.

In reviewing such heterogeneous research studies, it was not possible to meta-analyse the quantitative findings.

The qualitative papers report mainly on different interventions to those in the quantitative studies reviewed; therefore, we cannot conclude whether the intervention components staff reported as working well in qualitative studies were also associated with positive outcomes in the quantitative studies.

Background

There are 850 000 people living with dementia in the UK and the numbers are increasing, as they are globally.1 Around 300 000 people in the UK live in care homes, about 70% of whom have dementia.1 Many have complex needs with high levels of neuropsychiatric symptoms2 associated with lower quality of life and higher care costs.3 4 Public policy calls for high quality, evidence-based psychological interventions and an ‘informed and effective workforce’ to support people with dementia.5 6 However, care home staff are often poorly trained and paid little with high staff turnover.7–9

Reviews considering the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions in care homes have drawn mixed conclusions, reflecting the diversity of interventions, objectives and outcomes.10–14 A recent systematic review of non-pharmacological management of agitation concluded that supervised interventions which promote better communication, interaction and understanding between care home staff and people with dementia, including dementia care mapping (DCM) and person-centred care (PCC), can reduce agitation immediately and for up to 6 months afterwards.12

Authors of a recent review of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of non-pharmacological interventions for agitation and aggression in dementia, which included a narrower range of study designs, reported, in contrast, that overall, neither patient-level interventions (delivered directly to residents) nor care-delivery-level interventions (targeting how or the environment in which staff deliver care) were better than usual care in managing agitation and aggression.10 They concluded that existing evidence has troubling conceptual and methodological weaknesses, and that where individual studies show significant reductions in agitation, effect sizes are unlikely to be clinically meaningful.

Overall, although some psychosocial interventions are efficacious in managing specific neuropsychiatric symptoms in care home residents with dementia,12–14 positive effects are not sustained10–12 and rely on access to highly specialist external support.13 Additionally, there is little or no evidence of efficacy of stand-alone care home staff training unless ‘reinforcing’ (eg, additional supervision or individual skills training) or ‘enabling’ (time and help to put learning into practice) strategies are incorporated.15–17

To develop effective interventions for people with dementia living in care homes, we need to understand what works and how intervention effects can be sustained and embedded (ie, implementation) into practice after training. Quantitative reviews of efficacy in relation to defined outcomes can inform the former but have not until now informed the latter. Qualitative syntheses can inform implementation and translation of interventions from research into practice.18 Two existing studies have reviewed how psychosocial interventions for people with dementia in care homes have been implemented. The first (up to 2011)19 only reviewed qualitative studies, and the second (up to 2012)20 reviewed the effect of the interventions on staff knowledge, attitudes and skills but not resident outcomes.

Interventions are rarely implemented in the way they were carried out in trials, and findings of overall efficacy are generally conflicting.10 11 13 There is thus a need to understand which intervention components work, to inform real-world implementation. We have therefore (1) reviewed the evidence in quantitative intervention studies delineating what works immediately and where there is evidence of sustained effects on outcomes for people with dementia and care staff; and (2) synthesised qualitative research exploring what intervention components were considered to have worked by care home staff and other stakeholders and to have been practicable to implement. We intend that findings will inform the future development and implementation of sustainable psychosocial interventions.

Methods

Search strategy

We searched MEDLINE, PsychINFO and EMBASE with no restrictions on date or language of publication on 6 June 2014 and updated the search on 20 May 2016. We used the terms ‘care home’, ‘institution’, ‘24 hour care’, ‘residential home’, ‘nursing home’, ‘assisted living residence’ or ‘long-term care’ together with ‘staff’, ‘care worker*’, ‘nursing staff’, ‘care staff’, ‘care assistant*’ or ‘paid carer*’ and ‘intervention’, ‘training’, ‘staff training’, ‘staff education’ or ‘staff training intervention*’ combined with ‘dementia’, ‘Alzheimer’ or ‘vascular dementia’. References of included papers and relevant systematic reviews were hand searched for further papers (see online supplementary appendix 1 for a full search strategy).

bmjopen-2016-014177supp_appendix1.pdf (179.6KB, pdf)

Inclusion criteria

We included studies that fulfilled all the following criteria:

Primary research.

Quantitative with a control group (either individual or cluster RCTs or pre–post test studies with control conditions) or qualitative studies.

Evaluating psychosocial interventions without significant medical or drug care element, for example, review by pharmacists or physicians.

Either interventions that trained care home staff to deliver a specific intervention or that sought to change how care home staff delivered care to residents with dementia.

Reporting staff and resident outcomes.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded studies if:

The intervention was delivered directly to older people by external health or social care professionals.

Reporting on single-case studies and meeting abstracts.

PR read and screened titles and abstracts of studies. PR and CC independently read all retained papers. The decision to include or exclude papers was agreed by consensus.

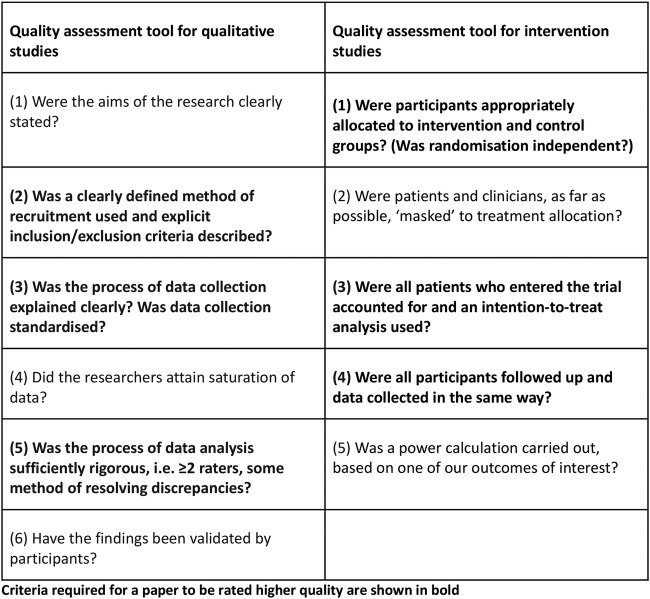

Assessment of quality

PR, CC and AM rated the quality of papers independently, using operationalised checklists and criteria for defining higher quality studies developed by our group21–23 from standard quality criteria24 (described in figure 1). Each quality checklist item scored 1 point; possible scores ranged from 0 to 6, with higher scores indicating better quality. We discussed discrepancies and reached consensus. For quantitative studies, we categorised papers as higher quality (ie, with a low risk of bias) if they: allocated participants to the intervention and control groups through independent randomisation, accounted for all participants who entered the trial and collected data and followed up participants in the same way (table 1, validity criteria 1, 3 and 4). For qualitative studies, we categorised papers as higher quality if they: used a clearly defined recruitment method, clearly stated inclusion and exclusion criteria, standardised data collection and involved two or more independent raters in data analysis (table 2, validity criteria 2, 3 and 5).

Figure 1.

Tools used to rate validity of qualitative and quantitative studies. Adapted from Mukadam et al,23 Cooper et al21 and Lord et al.22

Table 1.

Characteristics and quality ratings of high-quality quantitative studies

| n |

Control | n |

Validity criteria (see figure 1) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Recruitment source | Group training intervention | Staff | Resident | Staff | Resident | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| McCallion et al39 | Residents with ≥1 problem behaviour and nursing assistants on two US nursing facilities | NA Communication Skills Programme; 5x 45 min didactic and interactive group (3–6 NAs) sessions, manual and videos; 4× 30 min individual, personalised training, practice and feedback. Individual make-up sessions offered. Monthly follow-up sessions with facilitator for 3 months. Delivered by Masters social worker | 39 | 49 | WLC crossover at 6 months (followed up at 9 months) | 49 | 56 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Pellfolk et al51 | 40 group-dwelling dementia units with high levels of restraint use | Restraint minimisation education. 1 person per unit attended 2 days training. 6× 30 min video lectures for all staff with units facilitating group discussion of 3 vignettes | 156 | 149 | WLC | 133 | 139 | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Chenoweth et al;55 Jeon et al56 |

Staff and residents with needs-driven compromised behaviour in 15 Australian care homes using task-focused, not person-centred, care | PCC—2 days of training for 2 staff/site by experienced researchers+training manuals. Trained staff supported to develop and implement resident care plans. Regular telephone contact+2 visits during intervention. DCM—2 staff at each site, trained by expert, did DCM with researchers for 6 hours/day for 2 days; developed care plans and helped staff to implement them with regular phone support |

56 45 |

77 95 |

TAU | 23 | 64 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| van de Ven et al66 van de Ven et al63 |

Nursing staff and residents with ≥1 NPS in 34 units in 11 Dutch nursing homes | Training staff to implement DCM. Managers selected 2 staff per home to train and each home had a DCM briefing day with specialists. The trained mappers then completed at least 2 DCM cycles | 119 | 74 | TAU | 161 | 102 | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

CG, control group; DCM, Dementia Care Mapping; IG, intervention group; NA, nursing assistant; PCC, person-centred care; TAU, treatment as usual; WLC, wait list control.

Table 2.

Characteristics and quality ratings of high-quality qualitative studies

| Study | Recruitment Source | Method | N | Type of intervention | Focus of analysis/key themes | Validity criteria (see figure 1) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||||||

| Alnes et al72 Alnes et al73 | Staff in 4 Norwegian dementia care units | Focus groups, semistructured interviews, analysis of recorded intervention sessions and log kept by trainer | 24 staff participated in focus groups. 12 staff participated in semistructured interviews | MMC—a video-based counselling method to improve interaction skills. Staff received seven 1.5 hour weekly sessions over 2 months with an MMC trainer | Alnes et al—Nurses’ perception of learning from MMC. 2 overall themes were staff gaining new knowledge about themselves and the residents. Alnes et al—Factors that impact on learning outcomes of MMC intervention. Identified: (1) Establishing a common understanding of the content and form of MMC. (2) Ensuring that staff want to participate in and have the opportunity to do so. (3) Creating an arena for discussion and interactions during and after MMC |

Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N |

| Figueiredo et al75 Marques et al76 | Day staff in 1 Portuguese long-term care home | Pilot evaluation of staff training intervention included analysis of recorded morning care and postintervention focus group | 6 staff took part in training and 5 participated in the focus group | 8 psycho-educational sessions with staff with between session individual support. Intervention included staff support, multisensory stimulation and motor stimulation. Delivered by a multidisciplinary team and included homework and handouts | Figueiredo et al—Staff perspectives on structure and organisation and of benefits of the programme: (1) Acquisition of new knowledge and competencies. (2) Demystification of pre-existing beliefs. (3) Group cohesion. (4) Self-worth feelings. (5) Positive coping strategies. Marques et al—The impact of the motor and multisensory care-based approach on care practices, suggestions for future programmes, and difficulties putting into practice |

Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N |

| Kontos et al77 | Staff in 2 Canadian nursing homes | Postintervention focus groups and semistructured interviews. | 14 staff participated in 2 focus groups and 10 staff were individually interviewed | 12 week (2 hours each week) arts/drama informed educational intervention to improve person centred care. Used dialogue, critical reflection, role-play and dramatised vignettes | Staff perspectives on intervention. 2 main themes described: (1) Meaning beyond dementia—focused on how understanding behaviour facilitated care. (2) The influence of the approach to care—focused on how staff responses facilitate or inhibit person-centred care | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N |

| Veraik et al67 | Staff in 9 wards in Dutch nursing homes from an RCT intervention group | Semistructured interviews, questionnaire data and analysis of minutes, session reports and observations | 98 CNAs were trained. 20 CNAs were interviewed including 10 most and 10 least positive about the intervention | Guidelines for managing depression in dementia. Included: Printed educational materials, three interactive team training sessions and setting up promotion group on each ward | Analysed data from successful, moderately successful and unsuccessful implementation sites and analysed at multiple levels, nursing home, ward, CNA and resident levels. Presented case studies of successful/unsuccessful implementation and factors influencing successful introduction and application of the guideline intervention | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N |

CNS, certified nursing aides; MMC, Marte Meo counselling.

Synthesis and analysis of data

In our narrative synthesis of quantitative studies, we prioritised results from higher quality studies and findings on primary outcome measures. Results from lower quality quantitative studies are included in online supplementary table S1. As in our previous work,12 we decided a priori to meta-analyse when there were three or more RCTs investigating sufficiently homogeneous interventions and outcomes. No intervention met these criteria. There are no commonly agreed criteria for excluding qualitative studies based on quality;25–28 therefore, we included all qualitative studies in our ‘thematic synthesis’ of qualitative findings, in line with previous similar reviews19 28 and accepted methods.26 29 PR extracted data from the qualitative papers' results sections into NVIVO 9 software and inductively coded it in an open-ended, exploratory manner. CC reviewed the data and the coding frame; differences were discussed and codes refined. We then related our descriptive themes to our question of what components of interventions were considered to have worked and to have been practical to implement.30 31 PR developed overarching themes that synthesised the evidence and CC further refined emergent themes.

Results

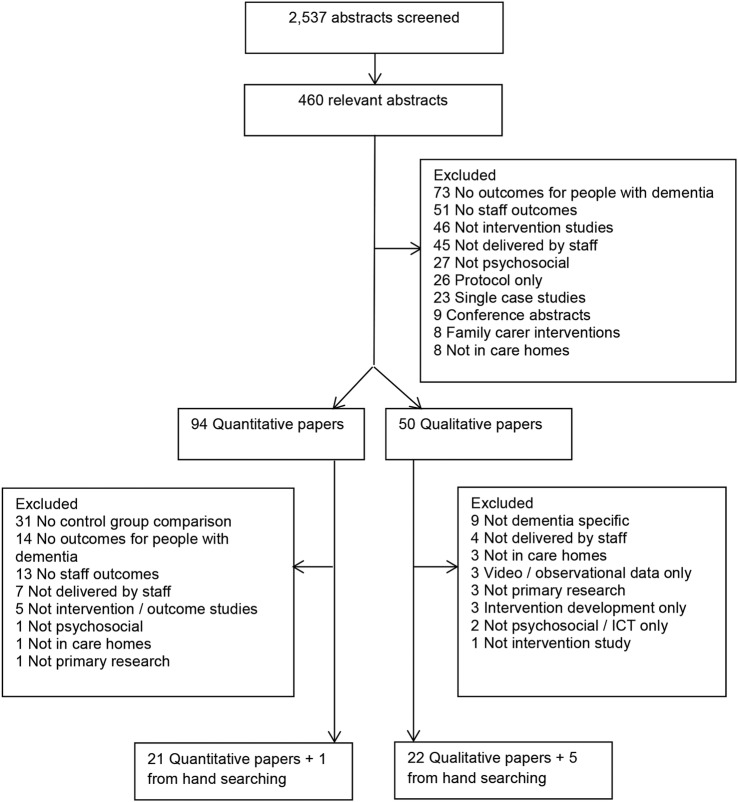

We identified 2537 unique, potentially eligible studies and included 49 relevant papers (see Prisma diagram figure 2 and online supplementary appendix 2 for the PRISMA checklist). We categorised 6 of the 27 qualitative papers and 6 of the 22 quantitative papers as higher quality. The relevant studies took place in the USA,32–43 Sweden,44–52 Australia,53–60 the Netherlands,61–67 the UK,68–70 Norway,71–74 Portugal,75 76 Canada,77 78 Ireland79 and Germany.80 They describe diverse interventions, including training and delivery of person-centred and relationship-focused care and DCM,36 37 40 43 44 52 53 55–57 59 63 66 68 72–74 78 79 training in dementia and managing difficult behaviour,41 42 58 60 80 communication skills and awareness training,32–34 38 39 62 64 69 creative and sensory interventions,45–47 61 65 70 71 75–77 staff supervision interventions,35 48–50 restraint minimisation51 and behavioural therapy interventions.67

Figure 2.

PRISMA diagram.

bmjopen-2016-014177supp_appendix2.pdf (198.7KB, pdf)

Findings from high-quality quantitative studies

The higher quality quantitative papers are described in table 1, and the lower quality quantitative papers are described in online supplementary table S1.

bmjopen-2016-014177supp_tables.pdf (795.2KB, pdf)

Group training interventions for care home staff with additional individual supervision

We identified one high-quality study that included individual skills training in addition to group training for nursing assistants.39 The training was designed to increase knowledge of dementia, communication and management of problem behaviours. It was tested in two US nursing homes in a crossover RCT. Resident physically aggressive behaviour in the intervention group decreased 3 months postintervention (F=17.59, p<0.001) relative to the control group, but this was not maintained at 6 months. However, verbally aggressive (F=14.23, p<0.001) and depressive symptoms (p<0.05) were significantly lower in the intervention group than the control group 6 months postintervention.

DCM interventions

Four papers described two high-quality RCTs55 56 63 66 evaluating DCM, a multicomponent, person-centred intervention. CADRES (Caring for Aged Dementia Care Resident Study)55 56 compared PCC and DCM with usual care in a three-arm RCT in 15 Australian care homes providing task-focused care. The DCM intervention included systematic observations of the well-being of people with dementia categorised and fed back to staff to support PCC. The mapping was completed by study experts and by trained care home staff. At the 4 month follow-up, resident agitation was lower in the DCM (10.1, 95% CI 0.7 to 21.1; p=0.04) and PCC (13.6, 95% CI 3.3 to 23.9; p=0.01) groups compared with the intervention group. Among staff, at the 4 month follow-up on three subscales of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), emotional exhaustion was lower in the DCM group than in the PCC and control groups (F=2.77, p=0.03), but there was no significant difference in depersonalisation or personal accomplishment. In another high-quality study which tested DCM in less tightly controlled settings, with care home staff delivering more of the intervention and without recruiting task-focused homes, no significant differences were identified between the intervention and control groups on primary staff or resident outcomes.63 66

Group training interventions for care home staff without additional supervision

A cluster RCT evaluated51 a restraint minimisation group training programme without additional supervision in 40 Swedish dementia units. Immediately postintervention, residents in the intervention group were restrained less than those in the control group (OR=0.35, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.83, p=0.02). Among staff who received the intervention, knowledge of restraint use (p=0.02) and dementia (p=0.01) increased significantly compared with staff in the control group, but there was no difference in staff attitudes towards restraint use. Longer term outcomes were not reported.

Findings from qualitative studies

We have synthesised findings from all included qualitative papers with at least one higher quality paper contributing to each main theme, with higher quality studies contributing to more subthemes than lower quality studies. The findings from the high-quality studies are presented in table 2 and findings from lower quality qualitative papers are presented in online supplementary table S2.

What works? Beneficial components of interventions

Improving communication

Staff across diverse studies described practices that improved interaction and communication with residents with dementia.37 44–49 52 53 59 65 68 70–72 75 76 78 79 These included interventions that focused on: initiating ‘meaningful conversation’ with residents during care;52 53 68 75 the emotional content of interactions,44–48 52 68 71 touch and physical contact,49 52 53 71 72 78 maintaining eye contact and using simple clear instruction.44 47 72 76 78 In addition to improvements in their own communication, staff described positive changes in residents' responses, noticing they were more responsive, happier and more cooperative.45 47 52 53 79 Giving residents time and space to respond was perceived as beneficial.48 49 52 53 65 71 72 78 Staff observed that by taking time to understand residents' responses, residents seemed more able to make decisions and actively participate in their care. Staff who participated in singing interventions45–47 found themselves talking and instructing less with residents understanding and expressing themselves more effectively.

Enhanced understanding of the residents

Staff reported that interventions enhanced their understanding of the residents.37 44–50 52 53 57 59 61 65 67 68 70–73 75–79 They felt more able to put themselves ‘in the client's shoes’78 and empathise with people with dementia,48–50 52 53 57 59 68 72–75 77–79 which was intrinsically rewarding.48 59 Staff reflected that this extended to understanding relatives' perspectives,48 53 59 resulting in improved relationships between staff and relatives.53 59 79

Staff across a range of studies recognised the importance of getting to know the person with dementia in order to provide more individualised and ‘person-centred’ care.45 48 49 52 53 59 68 70 71 77–79 This was achieved both by engaging people with dementia in activities where they could express their individuality such as dancing, singing and sensory activity;45–47 70 71 and through interventions which encouraged staff through training, supervision and experiential learning to find out more about care recipients.48 50 53 59 68 77 Developing staff knowledge of residents facilitated their understanding of the potential meaning of residents' behaviours, enabling them to alter their responses accordingly.37 44 52 53 59 68 71–73 77 79 Staff identified this as important for identifying residents' strengths and weaknesses48 49 53 57 59 72 75–77 79 and promoting independence when providing care.45–48 52 53 61 70 71 77–79

Reflection facilitates good practice

A common process underlying improved communication and understanding is an emphasis within interventions on staff reflecting on their practices. Staff appreciated the opportunity to consider their own and residents' interactions within experiential learning,77 interactive training,59 75 76 formal supervision48–50 71 or video feedback.37 41 44 46 48–50 52 71 72 75–78 This enabled them to identify patterns in their own and residents' behaviours,44 48 49 59 71 72 consider alternative reactions,44 48 49 71 72 77 and feel validated about helpful practices while recognising unhelpful practices and assumptions.41 59 67 76 78 79

Barriers and facilitators: individual factors

What gets in the way?

Staff across studies described the negative impact of providing care, particularly personal care, to people with dementia on themselves and their feelings about work.46 49 50 52 71 When faced with resistance and verbal and physical aggression, staff described frustration and distress.41 46 47 49 One carer described this struggle: “I wonder how long you can do this. … It is hard to fight every morning and only get anger back. … What should we do, we just have to live with it, right? I hide in the laundry room to catch my breath before caring for her.”46

Staff were sometimes reluctant to engage with interventions. For some, interventions promoting emotional and physical closeness led to fears of becoming attached to residents.44 52 70 Staff expressed doubts about their own ability to implement interventions,37 44 45 49 53 61 70 73 74 either in terms of having specific skills, such as being able to sing,45 61 or having the confidence to take on new roles, such as approaching relatives37 53 or coordinating care.74 There was initial scepticism from staff about engaging with interventions, especially if they were perceived to involve additional work, changes to existing ways of working45 49 53 59 65 67 or unfamiliar techniques.44 49 61 73 Negative responses towards interventions were more apparent when staff felt they did not accommodate the varying levels of education and experience within a team49 53 67 72 73 or the complex needs of those they cared for.52 61 67 74

What makes it easier?

A key facilitator of staff engagement was seeing benefits for staff and residents rather than being told of potential benefits by trainers, especially when staff saw positive changes in residents.37 45 46 48 52 53 57 59 61 65 67 70 72 75 76 79 In numerous studies, staff observed decreased agitation and aggressive behaviours, which they associated with the interventions.45 47 52 53 65 70 79 Staff identified a link between the impact of interventions on residents, and fewer difficulties providing care, a calmer and more relaxed atmosphere and improved relationships with residents and relatives.37 44–46 48–50 52 53 57 59 61 65 68 70 71 75–79

Having the opportunity to reflect on and adapt practices, using active and interactive learning methods was central to a number of interventions. Staff reported that group-based activities facilitated discussion and shared learning within teams57 67 75 and that role-play, the use of vignettes and analysis of filmed interactions supported understanding.44 49 61 75 77 Access to written materials including manuals, tip-sheets and hand-outs was valued when clearly written to accommodate the educational level of the staff.52 57 74 75

Barriers and facilitators: social and team factors

What gets in the way?

Lack of cooperation within teams was cited as a barrier to implementation, with staff identifying colleagues' unwillingness to help each other and poor communication as obstacles.65 67 76 78 Staff reported difficulties sharing new approaches with staff who had not attended training, especially those who had opted not to participate or held negative attitudes.44 53 59 67 73 74 Staff did not wish to be seen as telling colleagues what to do or felt that they lacked authority to do so.59 67 73 74 Lack of ownership of new interventions within the care team was cited as a barrier to initial implementation44 53 61 65 67 74 78 and maintaining positive changes after research trials.53 59 61 This was noted when staff felt that changes were imposed in a top-down way by managers or external professionals.53 67

What makes it easier?

Participants suggested that all staff should be included in training or new interventions to promote learning and help sustain practices.44 52 53 59 67 73 76 78 Staff also valued the opportunity to share learning within teams.44 53 57 61 65 67 73–75 77 Some interventions included formal structures, such as a ‘digital database’ for sharing ideas,61 or structured ‘consensus meetings’ led by team members, while others built discussion into existing forums or had informal discussions during routine care.65 67 74

Common across studies was the importance of on-site support to put skills into practice.53 57 61 65 67 73 75 This reinforced learning and gave staff opportunities to refine strategies and troubleshoot. Most studies included some support outside of formal training either as supervision and direct feedback on care37 41 44 48–50 52 61 71–76 or through on-site mentoring.37 53 57 59 65 67 78 Having on-site mentors trained as part of the intervention has the benefit of being sustainable postintervention but relies on committed individuals within the home who require additional support.37 53 59 65 67

Barriers and facilitators: organisational factors

What gets in the way?

Lack of time was raised as a barrier across most studies in relation to finding time to attend training and supervision and put learning into practice.44 52 65 73 74 79 When interventions required staff to set up additional project meetings, it was noted that these happened infrequently65 74 and more intensive interventions, requiring additional activities, such as detailed care plans and indepth observation, were difficult to sustain,44 52 53 61 65 67 74 particularly when staff felt that research teams were unclear about the time commitment required.44 61 Staff identified incompatibility between their busy, pressurised shifts and interventions that required them to engage with residents at a slower pace, shifting from a task-focused to a relationship-centred approach.44 59 78 79 High staff turnover and low staffing ratios were also barriers. In addition to an increased workload, lack of consistency in staffing resulted in less opportunity for shared learning, less coordination within teams and less familiarity with residents.48 53 61 65 67 73 76 78

Parallel change, such as organisational restructuring, new IT systems or new training initiatives were seen to hinder implementation.59 67 78 Although management and care home policy promoted a ‘person-centred’ approach, in practice staff felt that task completion remained a priority for managers and peers.41 44 53 59 67 70 One staff member commented: “I would rather be doing my care plans…because that is probably judged by others, whereas the project is not judged.”59 When staff felt unsupported by management, they found it difficult to prioritise new ways of working53 57 59 61 65 70 76 and teams were unmotivated when they felt they lacked the power to implement changes.67 73 74

What makes it easier?

Staff noted that management engagement with new interventions through attending training, contributing to project meetings or arranging cover for staff participation had positive effects,53 65 67 73 74 but in most studies, this was not the case. Being able to build the interventions into routine care was reported as central.44–46 48 61 65 68 70 75 78 79 Spending time talking to residents about their interests, reminiscing, singing to them or putting on a resident’s jewellery did not require additional time or resources and often made care provision more enjoyable for all.41 45 48 68 Sharing information via booklets left in a resident's room or in team discussions resulted in new strategies being sustained without requiring major changes to existing practices.48 65 68 Interventions consistent with existing approaches were valued.41 49 59 61 65 67 75 78 79 Benefits were reinforced when staff felt that giving more time to engage residents, rather than rushing to complete tasks, saved time overall as residents were more engaged, cooperative and less distressed.41 49 52 53 61 65 72 77 78

Discussion and conclusions

Key findings

We found a paucity of higher quality evidence that effects could be sustained after care home psychosocial interventions finished and there was no evidence that any interventions continued to work after 6 months. In one higher quality study, an individual and group programme with monthly follow-up sessions39 decreased resident physical aggression after 3 months and resident depressive symptoms and verbal aggression up to 6 months later. This may relate to their inclusion of monthly top-up sessions in addition to group and individual skills training, highlighting the benefits of ‘reinforcing’ strategies.15 This is consistent with our qualitative findings. Staff found individualised support to put new approaches into practice and to sustain beneficial interventions. In one higher quality trial,51 training staff champions to implement a video case vignette training programme increased staff knowledge and decreased restraint use immediately; while evidence for DCM and PCC was mixed, with positive findings from an Australian study55 56 not replicated in a more pragmatic, real-world care home environment.63 66

The findings from the lower quality studies were consistent with our conclusions from higher quality studies. They were, however, more heterogeneous in terms of outcomes, type and intensity of interventions and study designs. Lower quality interventions offering no follow-up supervision or support demonstrated no effect on resident symptoms. Interventions which included individual skills training or supervision in addition to didactic group-based training were associated with reduced resident neuropsychiatric symptoms and improved care delivery skills among staff. In our qualitative synthesis, consistent with previous reviews,14 19 we found that staff valued interventions that encouraged staff to get to know, understand and connect with residents with dementia. Interventions perceived as too intensive and complex for staff to put into practice, or as separate from rather than building on existing practices, were difficult to sustain. Staff described a number of beneficial ‘enabling’ practices such as having on-site mentors and opportunities to share new learning.

Implications for clinical practice

Sustaining effects of psychosocial interventions in real-world care home environments after research teams move on is challenging and rarely accomplished. Our qualitative synthesis highlighted the components and characteristics of interventions that staff considered important for achieving this. Interventions should be interactive and staff should retain materials after the groups are finished. Focusing on the benefits of the interventions for staff, residents and their relatives within training and giving staff opportunities to experience the impact of interventions by practising skills between sessions and reflecting on what works may motivate staff to continue to use and embed skills in routine care. Interventions need to fit into day-to-day care, avoid lengthy record-keeping or intensive observations and should save more time than they take. Including management in training and holding separate sessions with management and senior staff can support implementation. Having management support to train all staff is likely to make the role of on-site mentors more achievable, increasing shared responsibility across teams.

Strengths and limitations of this review

We reviewed studies testing a broad range of interventions, using qualitative and quantitative methods. This heterogeneity meant that it was not possible to meta-analyse quantitative data. By only including quantitative studies that report outcomes for staff and residents, we have excluded high-quality RCTs that may have provided further insights into the questions being addressed. However, without considering the effects of interventions on residents and staff, it is difficult to understand how altering staff practices impacts on care home residents.

The included qualitative papers report on interventions that were largely different from those in the quantitative studies reviewed, although there was overlap in the nature of the interventions. We cannot therefore conclude whether the intervention components staff reported in qualitative studies to work well were also associated with positive outcomes in the quantitative studies. However, staff training and support interventions would only be expected to ‘work’ if staff or home management change practice, and managers and staff generally only adopt new ways of working if they believe they make life better for the home, the staff or the residents. Consequently, qualitative studies that ask care home staff what components of interventions improved care delivery and how, provide useful evidence in an area where many trial results have been disappointing.

Future research

Within this review, we have highlighted some of the beneficial intervention components and the potential barriers and facilitators to implementing psychosocial interventions in care homes. To fully understand what works in dementia care, studies need to report fully on the process of implementation, including full reporting on adherence and treatment fidelity, using a combination of qualitative and quantitative measures.81 82 Very few of the quantitative studies gave details on attendance at sessions, how accurately staff were picking up new skills or how much staff were applying new learning or included any qualitative exploration of the process. Future RCTs in this area should consider implementation strategy from the outset and can draw on these findings to address the inherent challenges of embedding psychosocial interventions into care home settings.82

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors made a substantial contribution to this work. PR, GL, JM and CC all contributed to the conception and design of the review and PR drafted the paper. All authors critically revised it and gave final approval for this version to be published. PR read and screened titles and abstracts of studies and PR and CC independently read all retained papers. PR, CC and AM rated the quality of the quantitative papers and PR and CC rated the quality of the qualitative papers.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. PR's salary is part funded from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) funded programme grant MARQUE: Managing agitation and raising quality of life for people with moderate/severe dementia (ES/L001780/1).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Details of excluded papers and the qualitative data synthesis are available from the first author on request.

References

- 1.Prince M, Knapp M, Guerchet M et al. Dementia UK: update. London: Alzheimer's Society, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballard CG, Margallo-Lana M, Fossey J et al. A 1-year follow-up study of behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia among people in care environments. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62:631–6. 10.4088/JCP.v62n0810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okura T, Plassman BL, Steffens DC et al. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms and their association with functional limitations in older adults in the United States: the aging, demographics, and memory study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:330–7. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02680.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morris S, Patel N, Baio G et al. Monetary costs of agitation in older adults with Alzheimer's disease in the UK: prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007382 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Health. Living well with Dementia: A National Dementia Strategy. London: Department of Health, 2009.

- 6.Department of Health. Prime Minister's challenge on dementia 2020. London: Department of Health, 2015.

- 7.Franklin B. The future care workforce. London: ILC-UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pitfield C, Shahriyarmolki K, Livingston G. A systematic review of stress in staff caring for people with dementia living in 24-hour care settings. Int Psychogeriatr 2011;23:4–9. 10.1017/S1041610210000542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Testad I, Mikkelsen A, Ballard C et al. Health and well-being in care staff and their relations to organizational and psychosocial factors, care staff and resident factors in nursing homes. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2010;25:789–97. 10.1002/gps.2419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brasure M, Jutkowitz E, Fuchs E et al. Nonpharmacologic interventions for agitation and aggression in dementia. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jutkowitz E, Brasure M, Fuchs E et al. Care-delivery interventions to manage agitation and aggression in dementia nursing home and assisted living residents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016;64:477–88. 10.1111/jgs.13936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Livingston G, Kelly L, Lewis-Holmes E et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for agitation in dementia: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Br J Psychiatry 2014;205:436–42. 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.141119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seitz DP, Brisbin S, Herrmann N et al. Efficacy and feasibility of nonpharmacological interventions for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia in long term care: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2012;13:503–06.e2. 10.1016/j.jamda.2011.12.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Testad I, Corbett A, Aarsland D et al. The value of personalized psychosocial interventions to address behavioral and psychological symptoms in people with dementia living in care home settings: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr 2014;26:1083–98. 10.1017/S1041610214000131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuske B, Hanns S, Luck T et al. Nursing home staff training in dementia care: a systematic review of evaluated programs. Int Psychogeriatr 2007;19:818–41. 10.1017/S1041610206004352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fossey J, Masson S, Stafford J et al. The disconnect between evidence and practice: a systematic review of person-centred interventions and training manuals for care home staff working with people with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2014;29:797–807. 10.1002/gps.4072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spector A, Orrell M, Goyder J. A systematic review of staff training interventions to reduce the behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. Ageing Res Rev 2013;12:354–64. 10.1016/j.arr.2012.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orrell M. The new generation of psychosocial interventions for dementia care. Br J Psychiatry 2012;201:342–3. 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.107771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawrence V, Fossey J, Ballard C et al. Improving quality of life for people with dementia in care homes: making psychosocial interventions work. Br J Psychiatry 2012;201:344–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boersma P, van Weert JC, Lakerveld J et al. The art of successful implementation of psychosocial interventions in residential dementia care: a systematic review of the literature based on the RE-AIM framework. Int Psychogeriatr 2015;27:19–35. 10.1017/S1041610214001409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooper C, Ketley D, Livingston G. Systematic review and meta-analysis to estimate potential recruitment to dementia intervention studies. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2014;29:515–25. 10.1002/gps.4034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lord K, Livingston G, Cooper C. A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to and interventions for proxy decision-making by family carers of people with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr 2015;27:1301–12. 10.1017/S1041610215000411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mukadam N, Cooper C, Livingston G. A systematic review of ethnicity and pathways to care in dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2011;26:12–20. 10.1002/gps.2484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Programme.2006 CAS. 10 questions to help you make sense of qualitative research. England: Public Health Resource Unit, 2016. [updated 2016]. http://www.phru.nhs.uk/Doc_Links/Qualitative%20Appraisal%20Tool. pdf [Google Scholar]

- 25.Campbell R, Pound P, Morgan M et al. Evaluating meta-ethnography: systematic analysis and synthesis of qualitative research. Health Technol Assess 2011;15:1–164. 10.3310/hta15430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D et al. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10:45–53. 10.1258/1355819052801804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pope C, Mays N, Popay J. How can we synthesize qualitative and quantitative evidence for healthcare policy-makers and managers?. Healthc Manage Forum 2006;19:27–31. 10.1016/S0840-4704(10)60079-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychology 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grol RP, Bosch MC, Hulscher ME et al. Planning and studying improvement in patient care: the use of theoretical perspectives. Milbank Q 2007;85:93–138. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00478.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.French SD, Green SE, O'Connor DA et al. Developing theory-informed behaviour change interventions to implement evidence into practice: a systematic approach using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Implement Sci 2012;7:38 10.1186/1748-5908-7-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bourgeois MS, Dijkstra K, Burgio LD et al. Communication skills training for nursing aides of residents with dementia: the impact of measuring performance. Clin Gerontol 2004;27:2004–138. 10.1300/J018v27n01_10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bourgeois MS, Dijkstra K, Burgio L et al. Memory aids as an augmentative and alternative communication strategy for nursing home residents with dementia. Augment Altern Comm 2001;17:196–210. 10.1080/aac.17.3.196.210 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burgio LD, Allen-Burge R, Roth DL et al. Come talk with me: improving communication between nursing assistants and nursing home residents during care routines. Gerontologist 2001;41:2001–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burgio LD, Stevens A, Burgio KL et al. Teaching and maintaining behavior management skills in the nursing home. Gerontologist 2002;42:487–96. 10.1093/geront/42.4.487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoeffer B, Talerico KA, Rasin J et al. Assisting cognitively impaired nursing home residents with bathing: effects of two bathing interventions on caregiving. Gerontologist 2006;46:524–32. 10.1093/geront/46.4.524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kemeny B, Boettcher IF, Deshon RP et al. Postintervention focus groups: toward sustaining care. J Gerontol Nurs 2004;30:4–9. 10.3928/0098-9134-20040801-04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Magai C, Cohen CI, Gomberg D. Impact of training dementia caregivers in sensitivity to nonverbal emotion signals. Int Psychogeriatr 2002;14:2002–38. 10.1017/S1041610202008256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCallion P, Toseland RW, Lacey D et al. Educating nursing assistants to communicate more effectively with nursing home residents with dementia. Gerontologist 1999;39:546–58. 10.1093/geront/39.5.546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sloane PD, Hoeffer B, Mitchell CM et al. Effect of person-centered showering and the towel bath on bathing-associated aggression, agitation, and discomfort in nursing home residents with dementia: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52:1795–804. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52501.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Teri L, McKenzie GL, LaFazia D et al. Improving dementia care in assisted living residences: addressing staff reactions to training. GeriatrNurs 2009;30:153–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Teri L, Huda P, Gibbons L et al. STAR: a dementia-specific training program for staff in assisted living residences. Gerontologist 2005;45:686–93. 10.1093/geront/45.5.686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wells DL, Dawson P, Sidani S et al. Effects of an abilities-focused program of morning care on residents who have dementia and on caregivers. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000;48:442–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Söderlund M, Norberg A, Hansebo G. Validation method training: nurses’ experiences and ratings of work climate. Int J Older People Nurs 2014;9:79–89. 10.1111/opn.12027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gotell E, Thunborg C, Soderlund A et al. Can caregiver singing improve person transfer situations in dementia care? Music Med 2012;4:237–44. 10.1177/1943862112457947 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hammar LM, Emami A, Engstrom G et al. Finding the key to communion—caregivers’ experience of ‘music therapeutic caregiving’ in dementia care: a qualitative analysis. Dementia (London) 2010;10:98–111. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hammar LM, Emami A, Engstrom G et al. Reactions of persons with dementia to caregivers singing in morning care situations. Open Nurs J 2010;4:35–41. 10.2174/1874434601004010035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hansebo G, Kihlgren M. Patient life stories and current situation as told by carers in nursing home wards. Clin Nurs Res 2000;9:260–79. 10.1177/10547730022158582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hansebo G, Kihlgren M. Carers’ reflections about their video-recorded interactions with patients suffering from severe dementia. J Clin Nurs 2001;10:737–47. 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2001.00558.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hansebo G, Kihlgren M. Nursing home care: changes after supervision. J Adv Nurs 2004;45:269–79. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02888.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pellfolk TJ, Gustafson Y, Bucht G et al. Effects of a restraint minimization program on staff knowledge, attitudes, and practice: a cluster randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:62–9. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02629.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Soderlund M, Norberg A, Hansebo G. Implementation of the validation method: nurses’ descriptions of caring relationships with residents with dementia disease. Dementia (London) 2012;11:569–87. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chenoweth L, Jeon YH, Stein-Parbury J et al. PerCEN trial participant perspectives on the implementation and outcomes of person-centered dementia care and environments. Int Psychogeriatr 2015;27:2045–57. 10.1017/S1041610215001350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moyle W, Venturato L, Cooke M et al. Evaluating the capabilities model of dementia care: a non-randomized controlled trial exploring resident quality of life and care staff attitudes and experiences. Int Psychogeriatr 2016;28:1091–100. 10.1017/S1041610216000296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chenoweth L, King MT, Jeon YH et al. Caring for Aged Dementia Care Resident Study (CADRES) of person-centred care, dementia-care mapping, and usual care in dementia: a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Neurol 2009;8:317–25. 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70045-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jeon YH, Luscombe G, Chenoweth L et al. Staff outcomes from the Caring for Aged Dementia Care REsident Study (CADRES): a cluster randomised trial. Int J Nurs Stud 2012;49:508–18. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cooke M, Moyle W, Venturato L et al. Evaluation of an education intervention to implement a capability model of dementia care. Dementia (London) 2014;13:613–25. 10.1177/1471301213480158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Davison TE, McCabe MP, Visser S et al. Controlled trial of dementia training with a peer support group for aged care staff. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007;22:868–73. 10.1002/gps.1754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moyle W, Venturato L, Cooke M et al. Promoting value in dementia care: staff, resident and family experience of the capabilities model of dementia care. Aging Ment Health 2013;17:587–94. 10.1080/13607863.2012.758233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Visser SM, McCabe MP, Hudgson C et al. Managing behavioural symptoms of dementia: effectiveness of staff education and peer support. Aging Ment Health 2008;12:47–55. 10.1080/13607860701366012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van Haeften-van Dijk AM, van Weert JC, Dröes RM. Implementing living room theatre activities for people with dementia on nursing home wards: a process evaluation study. Aging Ment Health 2015;19:536–47. 10.1080/13607863.2014.955459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sprangers S, Dijkstra K, Romijn-Luijten A. Communication skills training in a nursing home: effects of a brief intervention on residents and nursing aides. Clin Interv Aging 2015;10:311–19. 10.2147/CIA.S73053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van de Ven G, Draskovic I, van Herpen E et al. The economics of dementia-care mapping in nursing homes: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e86662 10.1371/journal.pone.0086662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Finnema E, Droes RM, Ettema T et al. The effect of integrated emotion-oriented care versus usual care on elderly persons with dementia in the nursing home and on nursing assistants: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005;20: 330–43. 10.1002/gps.1286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Van Weert JC, Kerkstra A, Van Dulmen AM et al. The implementation of snoezelen in psychogeriatric care: an evaluation through the eyes of caregivers. Int J Nurs Stud 2004;41:397–409. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2003.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van de Ven G, Draskovic I, Adang EM et al. Effects of dementia-care mapping on residents and staff of care homes: a pragmatic cluster-randomised controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e67325 10.1371/journal.pone.0067325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Verkaik R, Francke AL, van Meijel B et al. Introducing a nursing guideline on depression in dementia: a multiple case study on influencing factors. Int J Nurs Stud 2011;48:1129–39. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brown WC, Swarbrick C, Pilling M et al. The senses in practice: enhancing the quality of care for residents with dementia in care homes. J Adv Nurs 2013;69:77–90. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06067.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Clare L, Whitaker R, Woods RT et al. AwareCare: a pilot randomized controlled trial of an awareness-based staff training intervention to improve quality of life for residents with severe dementia in long-term care settings. Int Psychogeriatr 2013;25:128–39. 10.1017/S1041610212001226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Guzman-Garcia A, Mukaetova-Ladinska E, James I. Introducing a Latin ballroom dance class to people with dementia living in care homes, benefits and concerns: a pilot study. Dementia (London) 2013;12:523–35. 10.1177/1471301211429753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lykkeslet E, Gjengedal E, Skrondal T et al. Sensory stimulation—a way of creating mutual relations in dementia care. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 2014;9:23888 10.3402/qhw.v9.23888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Alnes RE, Kirkevold M, Skovdahl K. Insights gained through Marte Meo counselling: experiences of nurses in dementia specific care units. Int J Older People Nurs 2011;6:123–32. 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2010.00229.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Alnes RE, Kirkevold M, Skovdahl K. The influence of the learning climate on learning outcomes from Marte Meo counselling in dementia care. J Nurs Manag 2013;21:130–40. 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2012.01436.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Røsvik J, Kirkevold M, Engedal K et al. A model for using the VIPS framework for person-centred care for persons with dementia in nursing homes: a qualitative evaluative study. Int J Older People Nurs 2011;6:227–36. 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2011.00290.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Figueiredo D, Barbosa A, Cruz J et al. Empowering staff in dementia long-term care: towards a more supportive approach to interventions. Educ Gerontol 2013;39:413–27. 10.1080/03601277.2012.701105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Marques A, Cruz J, Barbosa A et al. Motor and multisensory care-based approach in dementia: long-term effects of a pilot study. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2013;28:24–34. 10.1177/1533317512466691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kontos PC, Mitchell GJ, Mistry B et al. Using drama to improve person-centred dementia care. Int J Older People Nurs 2010;5:159–68. 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2010.00221.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Viau-Guay A, Bellemare M, Feillou I et al. Person-centered care training in long-term care settings: usefulness and facility of transfer into practice. Can J Aging 2013;32:57–72. 10.1017/S0714980812000426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cooney A, Hunter A, Murphy K et al. ‘Seeing me through my memories’: a grounded theory study on using reminiscence with people with dementia living in long-term care. J Clin Nurs 2014;23:3564–74. 10.1111/jocn.12645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kuske B, Luck T, Hanns S et al. Training in dementia care: a cluster-randomized controlled trial of a training program for nursing home staff in Germany. Int Psychogeriatr 2009;21:295–308. 10.1017/S1041610208008387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Holle D, Roes M, Buscher I et al. Process evaluation of the implementation of dementia-specific case conferences in nursing homes (FallDem): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2014;15:485 10.1186/1745-6215-15-485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vernooij-Dassen M, Moniz-Cook E. Raising the standard of applied dementia care research: addressing the implementation error. Aging Ment Health 2014;18:809–14. 10.1080/13607863.2014.899977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-014177supp_appendix1.pdf (179.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-014177supp_appendix2.pdf (198.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-014177supp_tables.pdf (795.2KB, pdf)