Abstract

Objectives

The incidence and prevalence of allergies worldwide has been increasing and allergy services globally are unable to keep up with this increase in demand. This systematic review aims to understand the delivery of allergy services worldwide, challenges faced and future directions for service delivery.

Methods

A systematic scoping review of Ovid, EMBASE, HMIC, CINAHL, Cochrane, DARE, NHS EED and INAHTA databases was carried out using predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Data on the geographical region, study design and treatment pathways described were collected, and the findings were narratively reported. This review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

Results

205 publications were screened and 27 selected for review. Only 3 were prospective studies, and none included a control group. There were no eligible publications identified from North America, Africa, Australia and most parts of Asia. Most publications relate to allergy services in the UK. In general, allergy services globally appear not to have kept pace with increasing demand. The review suggests that primary care practitioners are not being adequately trained in allergy and that there is a paucity of appropriately trained specialists, especially in paediatric allergy. There appear to be considerable barriers to service improvement, including lack of political will and reluctance to allocate funds from local budgets.

Conclusions

Demand for allergy services appears to have significantly outpaced supply. Primary and secondary care pathways in allergy seem inadequate leading to poor referral practices, delays in patient management and consequently poor outcomes. Improvement of services requires strong public and political engagement. There is a need for well-planned, prospective studies in this area and a few are currently underway. There is no evidence to suggest that any given pathway of service provision is better than another although data from a few long-term, prospective studies look very promising.

Keywords: Allergy Services, PRIMARY CARE, Secondary Care, Systematic review, Scoping review

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The literature review was carried out using eight major databases and reporting followed the PRISMA guidelines.

This is comprehensive review of all the published reports and journal articles on allergy services.

No eligible publications were identified from large geographical areas such as North America, Africa, Australia and most of Asia; most publications were UK based.

Service pathways for allergy and eczema were considered in the review.

Introduction

The incidence and prevalence of allergic diseases has been steadily increasing globally.1 It is recognised that there has been an increase in the prevalence of allergies in children and young adults with each passing decade.2 Despite this increasing need, allergy services have not improved worldwide.3 It is now well established that developed countries bear a higher burden of allergic disease.1 4–6 However, services rendered to the affected individuals in these higher income countries remain inadequate with deficiencies in primary and secondary care provision.3 7 The picture is similar across many countries with long waiting times for specialist appointments and wide heterogeneity in provision of primary care and specialist services.7 8 In addition, the growing incidence of serious allergic manifestations such as anaphylaxis9–12 as well as that of individuals with multiple, complex allergies13 has prompted calls for improved services worldwide.3 13

The UK has one of the highest rates of allergy and related diseases in the western hemisphere1 with a steady increase in the prevalence, severity and complexity of allergic disease in the last two to three decades.2 14–17 It is estimated that 30% of all adults and 40% of children in the UK will be affected by allergy-related conditions.18 Nevertheless, allergy services have remained ‘woefully poor’18 with very limited and patchy specialist service availability. This shortfall in service availability and the inherent heterogeneity of limited available services has been the focus of multiple expert body reviews in the UK, which have called for increased investment in allergy management and for reorganisation of allergy services.18–22

One of the major barriers to service planning in allergy is the lack of political engagement and reluctance to allocate funds from the local budget for improving allergy services.23 24 Allergy is not generally perceived as a serious condition with major implications for health and quality of life. There is a growing body of evidence to the contrary, however. It is now established that children with food allergies are more anxious than those with insulin-dependent diabetes and tend to have overprotective and very anxious parents.25 This is also true of adolescents with a history of anaphylaxis.26 In addition, the costs of allergies can be considerable. Allergy and related conditions are estimated to cost the UK NHS about £1 billion per year.27 Productivity losses associated with allergic rhinitis in the USA were higher than those due to stress, migraine and depression.28 Studies have shown that effective allergy services can not only improve quality of life, but can also be cost-saving.29 30 Hence, there is an urgent need to impress on policymakers the importance and wisdom of investing in the improvement of allergy services.

There is currently no agreement on how allergy services should be structured. In the UK and Europe, Primary Care Physicians – known as GPs or General Practitioners in the UK – (PCPs) diagnose and manage the majority of individuals with allergies7 whereas in Australia and the USA, specialist services provide the bulk of allergy care.8 Allergy service delivery by non-clinician practitioners such as pharmacists and dieticians, while possible, is not optimally used.22 Various pathways have been suggested and are being tested.23 31 32 However, it is not yet clear whether any particular model of service delivery may be preferable to the others.

The aim of this systematic review is to assess published approaches to allergy service delivery. The objective is to identify and appraise these publications to gain an understanding of the advantages as well as challenges associated with these service pathways; and also to explore current ideas regarding the future direction for these services.

Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed in conducting this systematic scoping review. The PRISMA checklist is supplied as online supplementary file S1.

bmjopen-2016-012647supp_PRISMA-checklist.pdf (335.6KB, pdf)

Data sources and search strategy

A systematic search of the literature was carried out to identify articles related to allergy service pathways in humans. Search terms included allergy, eczema, care, service and pathway (see online supplementary file S2). MEDLINE, EMBASE, HMIC, CINAHL, Cochrane, DARE, NHS EED and INAHTA websites were searched for the purposes of this review. Searches included publications indexed until the 4th of October 2016. In order for the MEDLINE searches to be relevant, we stipulated that two papers selected a priori3 33 should be identified in the search. References within the publications identified as relevant were individually examined to identify more articles of interest. Publications citing the chosen articles were also carefully examined for relevance.

bmjopen-2016-012647supp_Search-Strategy.pdf (7.8KB, pdf)

Selection of literature

After discarding duplicates, the title and abstract of the articles were examined for relevance. Where these were not informative, the full text of the publication was reviewed. Articles were included for review if they discussed pathways for the delivery of allergy or eczema services. Publications which reported opinions, conference abstracts, case reports or case series were excluded. Non-English language articles were not included in the review. Asthma service pathways were also not considered. One of the researchers (LD) carried out the searches with help and advice from an information specialist from the University of Birmingham. LD screened all the articles as per the predetermined criteria. A total of 50% of the unselected articles (25% each) were reviewed independently by two of the coauthors (TR and CC). Disagreements, if any, were resolved through discussion and consensus.

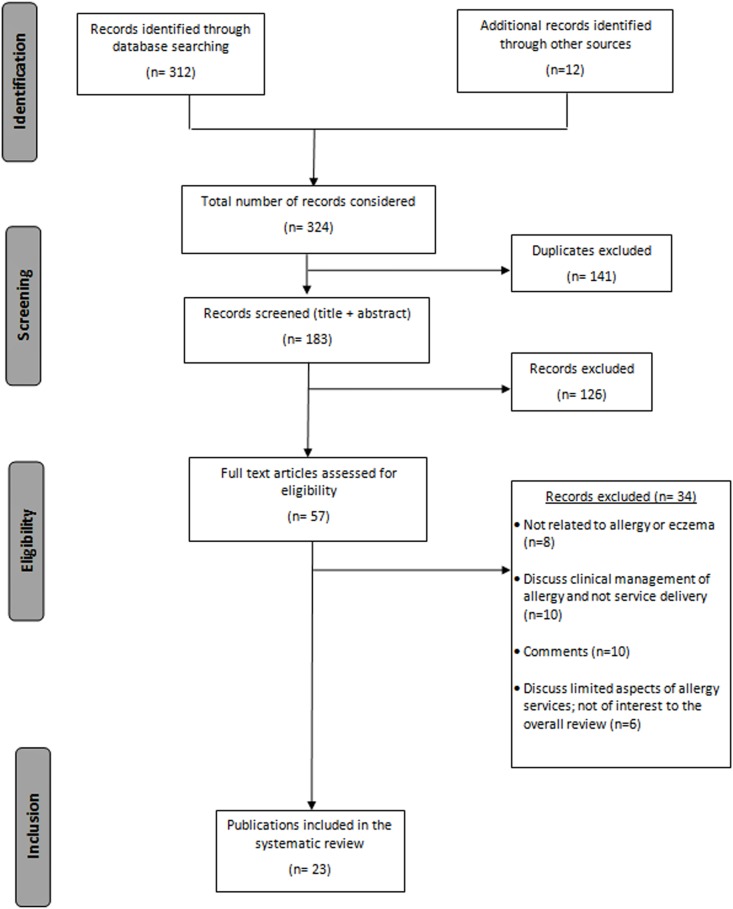

The PRISMA flow chart for selection of articles is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing the stages involved in choosing eligible publications for the systematic review (based on the PRISMA recommendations).

Data extraction and analysis

The data extraction form was piloted initially using a few publications. Appropriate modifications were made before starting the full extraction process.

The data were extracted by LD using extraction table that was previously agreed with the coauthors. Data extraction was scrutinised independently by two other authors (CC and TR).

For each publication, the author, year of publication, geographical region of interest, type of study (report, discussion, consensus, etc), study design (prospective, retrospective, cross section), treatment pathway (primary, secondary or both), principal findings and key recommendations were extracted.

Most of the articles were descriptive; hence the analysis followed a narrative synthesis. This is common in reviews of very heterogeneous studies which aim to describe and scope the area of interest.34 Since the objective of the report was to explore options for service delivery, the review was designed to be inclusive. Publications were, therefore, not excluded based on quality criteria but were described and briefly critiqued as appropriate given the nature of the studies. We aimed to map the current literature and understand the type of evidence available in this area (ie, allergy pathways).

Results

The database search identified 351 articles of which 158 were duplicates. Additional 12 articles were included following reference and citation searches. After consideration of the title and abstract, a further 142 articles were excluded and a total of 63 publications were screened thoroughly for their relevance to the review. Figure 1 shows a flow diagram of the papers screened, identified, retained or excluded at each stage, and the reasons for exclusion of articles as per the PRISMA guidelines.35

Twenty-seven publications were included in the final review which are summarised in table 1. Only three publications describe prospective data collection alongside service reorganisation.23 43 52 There were no eligible prospective, randomised controlled trials identified.

Table 1.

Summary of characteristics of the included publications (arranged in chronological order)

| Author, (year) (ref) | Level |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Type of study | Study aim | 1° | 2° | Salient findings | Key recommendations | Comments | |

| Isinkaye et al (2016)36 | UK | Retrospective cohort study | To ascertain what proportion of referrals to secondary care could be managed a by GP with special interest in allergy | ✓ |

|

|

|

|

| Krishna et al (2016)37 | UK | Report/non-systematic literature review | To discuss the potential use of telemedicine in pathways for diagnosis and management of adult allergies | ✓ | ✓ |

|

|

|

| Bousquet et al (2015)38 | Europe | Introduction of prospective study using Information and communications technology (ICT) methods. | Plan for study with ICT methods in allergy services. | ✓ | ✓ |

|

|

|

| Conlan et al (2015)39 | Ireland | Retrospective cohort study | Review of

|

✓ | ✓ |

|

|

|

| Chan et al (2015)40 | Hong Kong | Report | To discuss the current management of allergic disease in Hong Kong. | ✓ |

|

|

This is a report from the Hong Kong allergy alliance, whose members include patients, clinicians, academics, industry and other stake holders in allergy within Hong Kong. | |

| Jutel et al (2013)24 | Europe | Report/cross-section | To provide a contextual patient-centric framework based on opinion of PCPs, specialists and patients. | ✓ |

|

|

The authors of this publication belong to the EAACI Task Force for Allergy Management in Primary Care. | |

| Jones et al (2013)41 | UK | Survey/retrospective | To assess patients perception of usefulness of the secondary allergy clinic at Plymouth Hospital. | ✓ |

|

|

|

|

| Agache et al (2012)7 | Europe | Survey/cross-section | To assess the actual status of allergy management in primary care across Europe | ✓ |

|

|

|

|

| Sinnott et al (2011)23 | UK | Prospective planning and implementation of care pathways | Description of a pilot project undertaken to improve allergy services in the North of England. | ✓ |

|

|

|

|

| Warner and Lloyd (2011)42 | UK | Discussion/pathway development | Background for the development of paediatric allergy care pathways by the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) | ✓ | ✓ |

|

|

|

| Royal College of Physicians and the Royal College of Pathologists (2010)21 | UK | Report from a publicly funded organisation. | Recommendations to stakeholders in allergy for provision of cost-effective improvements in allergy care. An update on changes to allergy service provision following the House of Lords inquiry (2007) into allergy. |

✓ | ✓ |

|

|

|

| Levy et al (2009)43 | UK | Prospective; no control group. | Evaluation of a PCP with special interest clinic in allergy. | ✓ |

|

|

|

|

| Working group of the Scottish Medical and Scientific Advisory Committee (2009)22 | UK | Report from a publicly funded organisation. | To report on the diagnostic and clinical allergy services within Scotland | ✓ | ✓ |

|

|

|

| Haahtela et al (2008)32 | Finland | Prospective; intervention; no control group. | Nationwide allergy programme being adopted in Finland. Proposed to run between 2008 and 2018. | ✓ | ✓ |

|

|

|

| House of Lords Science and Technology Committee, 6th report of session 2006/7 (2007)18 | UK | Report from a publicly funded organisation | To explore the impact of allergy in the UK upon patients, society and the economy as a whole. | ✓ | ✓ |

|

|

|

| Department of Health (2007)44 | UK | Report from a publicly funded organisation. | Response to the report from the House of Lords Science and Technology Committee 2007. | ✓ | ✓ |

|

|

|

| Warner et al (2006)3 | Worldwide | Cross-section; Questionnaire survey. | To define the current state of allergy training and services in the countries represented within the WAO | ✓ |

|

|

|

|

| Department of Health (2006)45 | UK | Report from a publicly funded organisation. | Review of allergy services undertaken to fulfil Government of UK's commitment to the House of Commons Health Committee. | ✓ | ✓ |

|

|

|

| El-Shanawany et al (2005)46 | UK | Cross-section; Questionnaire Survey | To survey allergy services provided by clinical immunologists in the UK. | ✓ ✓ |

|

|

|

|

| Ryan et al (2005)47 | UK | Discussion | To propose minimum levels of knowledge required for clinicians in order to improve standards of allergy care. | ✓ | ✓ |

|

|

|

| Department of Health (2005)48 | UK | Report from a publicly funded organisation | Government of UK response to the House of Commons Health Committee report. | ✓ | ✓ |

|

|

|

| Levy et al (2004)49 | UK | Cross-section; Questionnaire survey | Understanding the views of PCPs in the UK regarding the quality of primary and secondary care for allergy. | ✓ |

|

|

|

|

| House of Commons Health Committee (2004)19 | UK | Report from a publicly funded organisation | To highlight the need for allergy service improvement in the UK | ✓ | ✓ |

|

|

|

| Royal College of Physicians (2003)20 | UK | Report from a publicly funded organisation. | To ensure that allergy services are prioritised for improvement by commissioners and managers in the NHS. | ✓ | ✓ |

|

|

|

| Ewan and Durham (2002)33 | UK | Discussion | Proposal to improve NHS allergy care in the UK | ✓ |

|

|

|

|

| Ewan (2000)50 | UK | Discussion | An overview of NHS allergy services and suggestions for improvement. | ✓ |

|

|

|

|

| Brydon (1993)51 | UK | Questionnaire; retrospective | A survey to determine the effectiveness of a nurse practitioner service. | ✓ |

|

|

|

|

BAF, British Allergy Foundation; BSACI, British Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology; DoH, Department of Health (UK); EAACI, European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology; MCN, Managed Clinical Network; NHS, National Health Service (UK); NICE, National Institute of Health and Care Excellence, UK; PCP, Primary Care Physician; PROM, Patient Reported Outcome Measures; WTE, Whole Time Equivalent; WAO, World Allergy Organisation.

Level: 1° (primary) refers to care delivered by primary care physicians, nurses and other practitioners who are non-specialist and offer services in the home or community.

2° (secondary) services refer to those provided in hospitals by clinicians (doctors or nurses) deemed to have specialist training and knowledge relevant to the management of the condition.

Seven of the publications discussed allergy services in other parts of the world,3 7 24 32 38–40 whereas the rest are focused specifically on services in the UK. Of the 19 UK papers, 8 are reports published by governmental organisations discussing the state of allergy services in the UK.18–22 44 45 48 One of these reports provides a brief overview on aspects of allergy services in other European countries (Germany and Denmark).18 Another summarises experiences following the establishment of a pilot allergy service in the North West of England.23

Reorganisation of primary care was addressed by seven articles, secondary care services were the focus of six publications, whereas four papers discuss both levels of care. The eight government reports discuss all aspects of service delivery (table 1). Three studies discussed the use of digital technology-based interventions for allergy,37–39 one of these retrospectively evaluated such a service.39 Findings, statements and recommendations about allergy service pathways from the included papers are reported in table 1 and are synthesised thematically.

Primary care services

PCPs in allergy service delivery

PCPs are the first-line providers of healthcare in most countries around Europe.24 They are well placed to provide diagnosis and management of mild and most of the moderate allergic conditions as well as to refer individuals with complex and severe allergies to specialist services.24 Many publications have identified that the training offered to PCPs in allergy currently is inadequate.18–23 47 49 The current inadequacies in training and the need for more information and training for PCPs in allergy were reinforced in studies reported from Scotland, Italy and Spain.7

It was argued in the two European publications that a model of care which is centred on specialists or consultants is untenable in allergy.7 24 In public-funded health systems such as the UK where PCPs assess and manage the majority of patients, the burden placed by allergy and related conditions on primary care could be significant. For example, it was estimated that allergy accounts for 8% of all general practice consultations in the UK and that up to 11% of the total drugs budget is spent on allergy-related medication (including asthma and eczema).18

One particular article mentioned the lack of access to secondary services as allergy's ‘greatest unmet need’.7 Referral times to specialists vary considerably across Europe from over 3 months in some tax-funded health systems7 20 22 40 to as little as 1 week when specialists can be accessed privately.7 Across Europe organ specialists are generally more readily accessible to PCPs than allergists.7 In a UK-based survey of over 480 PCPs, 81.5% of the 240 PCPs who responded felt that the NHS allergy services were poor and 80% felt that secondary care provision was inadequate.49 These practitioners admitted to being especially anxious about treating children with food allergies, although most felt quite confident about managing common allergic conditions such as anaphylaxis, urticaria, allergic rhinitis and drug allergy.49

PCPs with an interest in allergy

Two publications specifically discussed a second tier service for allergy within primary care.7 53 Such an arrangement was also proposed by the House of Lords report.18 In the UK, a prospective evaluation of patients referred to a General Practitioner with Special Interest (GPwSI) in allergy revealed that the services were well received, reduced the levels of secondary care referral and had a potential for cost savings.43 Further, PCPs in this study referred patients more readily to the GPwSI than to secondary care.43 However, establishing these services would need a well-defined process of accreditation and specialist mentorship24 which may be difficult to achieve in most countries given the current severe shortage in the availability of specialists across Europe.3 24

Non-physician services in primary care

Non-physician services for allergy were specifically discussed by six publications in this review.18 20 22 44 47 51 Most of the articles discuss the underusage of these professionals in allergy and suggest that there is a scope for better training of nurses, pharmacists and dieticians in allergy. Depending on the extent of training and the competencies achieved, nurses could be involved with testing, diagnosis and management of patients with allergy.47

Some authors felt that pharmacists could, if adequately trained and sufficiently supervised, provide information to patients regarding techniques for using devices such as nasal sprays, eye drops, epinephrine auto-injectors as well as inhalers for allergy and related conditions.18 47 They could help patients choose over the counter medication for allergy judiciously. They can also be trained to advice individuals on the need for consultation with their PCP, where appropriate.22 The House of Lords committee suggested that pharmacists should be formally trained in allergy to ensure that good quality advice on allergy medication can be provided to all patients.18 This committee also reported concerns from clinicians regarding availability of unvalidated tests over the counter for allergies in some establishments.18 There are, however, no publications to-date formally assessing the role of pharmacists in the diagnosis and management of allergy.

Barriers to providing optimal allergy care in the primary care sector

Several authors were concerned that PCPs do not receive structured instruction in allergy during their training, and very few are familiar with guidelines for the management of allergic disease.7 20–22 33 The House of Commons health committee highlighted the lack of allergy knowledge in primary care as “…one of the principal causes of distress to patients”.19 Some articles have specifically highlighted the significant gaps in allergy training at the undergraduate and postgraduate levels, as well as inadequate continuing medical education programmes for PCPs in allergy.20 21 24 This was identified as leading to inappropriate referrals to a range of specialists,23 lack of engagement with secondary care services for allergy, delays in diagnosis and starting appropriate management20 and, sometimes, to inappropriate management.33 All these issues resulted in poor patient experience and also cause a significant wastage of scarce healthcare resources.20 21 A retrospective review of the patients at a secondary care allergy clinic in Sussex showed that at least 42% of patients were referred for conditions that could have easily been managed in primary care, had the PCPs been appropriately trained.36 An Irish study also suggested that increasing awareness of common allergic conditions among PCPs can significantly reduce referrals to specialists.54 This suggestion was reinforced in UK government reports19–22 and other studies.23

In most countries, the lack of leadership and support offered by a stable, well-staffed specialist service was identified as one of the main barriers to improvement of primary care services.7 18–21

Secondary care services

Availability of specialist services

A publication by the World Allergy Organisation (WAO) has suggested that there is a great degree of heterogeneity in access to specialist allergy services across the world.3 40 Experts point out that while there has been very little increase in availability over the last few years, the demand for specialist allergy services has been steadily increasing.21 For example, the number of certified allergy specialists per head of population range from 1:25 million (in Malaysia) to about 1:2 million (in the UK) and 1:16 000 (in Germany).3

Heterogeneity in specialist training has also been highlighted3 33 with only a few countries providing certified courses to practitioners in allergy. A worldwide study by the WAO showed that paediatric allergy services are particularly underserved and children with allergic problems are often managed by general paediatricians with or without formal allergy training.3 This study also found that in many countries children may be managed by specialist adult physicians without appropriate paediatric training.3 Specialist training pathways for allergy vary markedly worldwide. In countries such as the UK, formal certification procedures in either allergy alone or in a combination of allergy and immunology exist. Similarly, in the USA, allergists/immunologists should have passed a professional examination taken after 2 years of structured specialty training. In other countries, allergy may be included as a subspecialty in general internal medicine or paediatrics training.3 In Germany, for example, allergology is considered a subspecialty of dermatology.18 In the UK, the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology (BSACI) has estimated that 90% of secondary care in the UK is provided by allergists and immunologists.45 A study carried out in the UK has shown that immunologists, who have formal training in allergy, provide allergy care to 32 million individuals in the UK.46 Some authors have pointed out that immunologists are indeed the sole providers of allergy services in parts of the UK.44 46 Other specialists such as those with primary qualifications in ENT, respiratory medicine or dermatology also contribute to the delivery of allergy services in many countries3 including about 10% of the total secondary care for allergy in the UK.45 Even if this broad definition of allergy specialists were to be accepted, many experts feel that allergy services remain inadequate in most countries in the face of increasing demand for these services.3 19 40

Specialist centres for allergy

Some authors propose the ‘hub and spoke’ model18–20 40 which involves the establishment of supraregional tertiary allergy centres (or Hubs) which can support regional secondary and primary care centres (the so-called spokes) for delivery of specialist services. A few suggested that these centres should be manned by consultant adult and paediatric allergists, nurse specialists as well as adult and paediatric dieticians while providing facilities for training at least two specialist registrars in allergy.20 Others felt that these should be multispecialist centres (eg, chest physician, dermatologist, ENT specialist, paediatrician in addition to an allergist or clinical immunologist) that are built on existing expertise of the local area and serve as ‘clusters of expertise’.18 In some countries, these centres would typically be university hospitals which would receive referrals only from specialists.18

Whatever their composition, most agreed that these centres could serve to educate and support primary and secondary care physicians in the region.18–20 It was suggested that they had a potential to serve as centres of excellence for adults and children with complex and severe allergies; establish a good, working network between organ-based specialists, generalists and allergists and serve to improve the overall provision of allergy services in the region.18

Some experts point out that the existing shortage of specialists in allergy would be a barrier to the development of such centres.21 50 A pilot study carried out in the North West region of England found that developing large tertiary centres would not be practical in regions with large cities in close proximity to one another.23 They may not be cost-effective for many regions within the UK21 and perhaps, Europe.

The House of Commons health committee has pointed out that there are no clear data to suggest that specialist centres improve clinical outcomes in allergy management.19 41 Indeed, even in countries like Germany with a relatively high proportion of allergy specialists per 100 000 population, the numbers of emergency admissions for allergy remain high.3 The North East England pilot study found that the lack of confidence among general practitioners while dealing with patients with allergy led to poor referral practices.23 As a consequence, management of simple conditions took up a disproportionate amount of specialist time and resources while individuals with complex allergies faced long waiting lists as well as inappropriate referrals to other specialists.23

Future direction for services

While efforts are being made to improve allergy education at the undergraduate and postgraduate levels, there has been a focus also on the improvement of training of current practitioners. The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child health has developed care pathways for children which define core competencies for all those involved in managing these conditions and are freely accessible online.42 These are UK based but potentially can be modified to suit other countries. Such pathways embrace the current heterogeneity in service delivery while attempting to raise standards.

The ‘Hub and spokes’ model was trialled in the UK with mixed results, which was specifically discussed in a report.23 The authors suggested that new services should be tagged onto existing pathways and also stated that a care model of visiting specialists in secondary centres would be more welcome in some areas than the establishment of large tertiary centres.23 It was also suggested that models of good care can vary from one region to another.21 23

There have been recent publications regarding the use of digital technology in the provision of allergy services.37–39 One addresses the use of telemedicine in improving communications between primary and secondary care in order to improve adult allergy pathways within the NHS;37 whereas another makes a case for clinical trials using information communication and technology (ICT) in management of allergic rhinitis in Europe.38 A publication from Ireland reported on the use of an email communication system, which received an average of only four enquiries per month over a 12-month period. Although it was rated useful by 100% of the responding non-specialists (response rate of 35%), this communication system did not reduce referrals to the specialist allergy services.39

There has been a lot of interest lately in the ‘Finnish model’ of service reorganisation. This re-structuring exercise takes inspiration from the successful interventions for asthma in Finland.32 While acknowledging the differences between asthma and allergy and emphasising the need to understand and improve tolerance to allergens, the architects of this model hope to use the existing asthma infrastructure to improve services for allergy sufferers. They suggest that increased initial outlay aimed at preventing allergies and changing attitudes towards health alongside improving service delivery can reduce the cost and burden of allergic disease in the future.32 The results of this experiment are currently awaited.

Discussion

Principal findings of the review

This systematic review aimed to identify and discuss various pathways that are relevant to the delivery of allergy services. There were large gaps in the literature pertaining to services in countries with high rates of allergy (such as Australia, New Zealand, USA)1 5 as well as very populous regions of the world including China, India, Brazil and the whole of Africa. In addition, there was a lack of well-designed studies in this area with only three prospective studies identified.23 32 43 None of the studies included a control group. Two of these publications23 32 describe service reorganisation on a large scale with direct involvement of the relevant health ministries.

There is clear evidence from the literature that allergy services across the world have not kept up with rising demand. The ‘allergy epidemic’13 has surprised unprepared health systems globally. There has been failure on the part of governments and fund holders to acknowledge the rapid rise in allergies. Given that there are no signs of abatement in the observed increase in allergies worldwide,2 it is conceivable that the demand on services is set to increase even higher over the next few years. The psychosocial impact of these conditions is often overlooked. For example, atopic individuals experience significantly worse memory and cognitive ability during allergy season.55 Children with eczema report higher levels of anxiety and depression.56 In addition, these conditions currently place an inordinate financial burden on healthcare services.29 57 58 Urgent and effective measures are therefore needed to cope with the problem.

About three-quarters of the eligible publications in this review (18/23) are from the UK which suggests that there has been a lot of interest here in investigating the extent of the supply gap in allergy services over the last 15 years. It is striking however, that while most of these reports describe the problems with service delivery and suggest some solutions, none seem to have addressed the problem in a structured manner. There has been no response to the UK Department of Health's request for reliable baseline data on needs of the population; costs involved in service reorganisation; and the skills and competencies of the existing workforce in order that future services can be planned.44 45 48

Primary care services are key to optimal management of allergy. Appropriate management after good history taking and specific testing can easily be achieved in primary care for a majority of patients. Referral to specialist centres can be limited to only complex patients needing multidisciplinary input or those that need desensitisation therapy. However, a UK survey has shown that PCP confidence in managing allergies in children49 and initiating referrals appropriately is limited. While PCPs in this particular survey felt confident about managing adults, studies have shown that most individuals referred to secondary care could have been managed effectively in primary care.23 54 59 This serves to highlight the inadequate training received by PCPs in allergy at undergraduate and postgraduate levels. This leads to not only poor patient experience and outcomes but is also more expensive to the health service providers.

Owing to lack of specialists in allergy, patients are often referred to specialists who can, perhaps, only deal with individual manifestations of allergy (eg, respiratory physicians for allergic asthma; ophthalmologists for allergic eye disease). Organ-based specialists play a very important role in the management of allergic disease. Indeed, in some instances (eg, children with very severe disease), their input is essential. However, specialists in allergy can provide clinically effective and potentially cost-effective services by intervening across several of these conditions for most patients.20

Scarcity and inequity of specialist allergy services is a recurring theme in many articles worldwide. Although numerous publications have made a compelling case for more specialist centres,3 18–21 33 these have not been forthcoming. Many factors appear to contribute to this apparent inertia,21 the important ones being lack of adequate central funding to increase training numbers for specialists, lack of interest in allergy services among fund holders,23 lack of clarity regarding the role of various specialists involved.21 Another important issue is the lack of formal training programmes in allergy in many countries.3 This not only blights the care of individuals with allergy in these countries, but also prevents the specialty being taken seriously by decision makers. In the case of the UK, lack of clinical codes to measure allergy activity and disagreements between the two main specialist groups that provide allergy services (allergists and immunologists) are also important issues.48 Further, in the UK, the lack of specialist services and poor referral practices within primary care have resulted in unreliable waiting list data, which are often used as a surrogate marker for need within the NHS.44 This has proved to be a barrier for further investment in services.48

It should be noted that there are no published data that support the success of large, tertiary centres. Nevertheless, it is conceivable that centres which treat large volumes of individuals will provide better outcomes for complicated patients.60 However, the lack of confidence among general practitioners while dealing with patients with allergy leads to poor referral practices leading to long waiting lists as well as inappropriate referrals to other specialists.23

There have been many encouraging advances in allergy service reorganisation in the UK and beyond. New multiconsultant allergy centres were created in the North West of England as per the recommendations of the House of Lords report into allergy services.18 This service development encountered many barriers including non-engagement of local commissioners, non-availability of appropriately trained staff and poor coding practices.23 Nevertheless, the project was successful in improving networking among specialists across the region, improved clinical governance including audit, better regional education programmes for clinical staff and patients in allergy.23 There was an opportunity during the course of this project to prospectively collect data on patient experiences and outcomes, which was unfortunately missed.

The heterogeneity in specialist training across Europe is also being addressed with the introduction of the European Examination in Allergology and Clinical Immunology since 2008 by the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI). The aim of this examination is to “raise standard of allergology and clinical immunology in Europe” and to “facilitate the exchange of young people trained in Allergology and Clinical Immunology” in Europe.61

The Finnish allergy model is based on the very successful restructuring of asthma care in Finland62 and is now being adapted to the management of other chronic conditions.63 In Finland, the model has been altered to incorporate the complex and heterogeneous nature of allergy but it essentially builds on the existing infrastructure developed for the asthma programme.32 The Finnish allergy plan is an ambitious project that aims to reduce the burden of allergic disease by improving tolerance and reducing the emphasis on allergen avoidance in affected individuals. The objective is to help alleviate the psychosocial aspects of allergy while improving services provided to these persons.32 Aspects of this plan have also been adopted by Norway64 and by a health authority in North West London as well as in Sheffield.65 Preliminary results from the London project are very encouraging.31 66 67 More data are awaited to ascertain whether the project has been successful and also if this success can be emulated in other regions.

Strengths and limitations of the review

The strength of this review is that it provides a systematic and comprehensive look at the reported current provision of allergy services across the world. There are some limitations to this review, mainly due to paucity of information from most countries, including some with relatively high allergy incidence and prevalence, regarding available services. Most of the literature is UK based and hence generalisability of data to other countries, especially those without publicly funded health systems may be limited. In addition, there were very few well-planned prospective studies and no controlled studies in this area. Most of the included studies had little empirical data, and therefore a formal quality assessment of the publications was not carried out. Studies not reported in the English language were excluded.

Strengths and limitations in relation to other studies

This paper is the first to comprehensively review all the published reports and journal articles on allergy services. Our review, in concurrence with a previous UK review,45 found that prospective studies in the area were lacking and that there were no data objectively comparing different levels of service delivery (eg, primary care vs secondary care).

Conclusions

There is a consensus that allergy services across the world are inadequate to meet the rising demand. There is a high degree of heterogeneity and inequity in the availability of services across the world. Untreated or poorly treated allergic conditions can have a high psychosocial impact on individuals and can place a substantial economic burden on healthcare services. Allergy training is not adequately provided in the current undergraduate and postgraduate medical curricula, which is adversely affecting patient care at all levels, especially in primary care. Primary care services are affected by poor training of practitioners and by poor access to specialists. Specialist services are hampered by the non-availability of appropriately trained personnel and poor referral practices from primary care (where applicable) which lead to long waiting lists and poor overall patient care. There is currently no clear consensus on how services should be structured although the Finnish model of service reorganisation has shown significant promise. Political engagement and patient empowerment are important to the success of these projects.

Future research

There is a need for data on service pathways from across the world, especially from countries with a high burden of allergic disease so that the extent of the problem can be identified and lessons may be learnt from successful models. Prospective data aimed at estimating the costs and outcomes of service pathways are especially important. To ensure that a service is successfully re-organised, it is important to understand the needs of the local population, their preferences for services and to estimate costs and benefits of the possible service pathways. This literature review forms part of a wider project which aims to achieve these objectives for the population of the West Midlands region of the UK.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Tracy Roberts @tracyrobertsbham

Contributors: All the authors contributed significantly to the planning, execution of this review and to the preparation of the manuscript. LD carried out the systematic review and wrote the manuscript. CC, RL and TR regularly reviewed the work and provided advice.

Funding: This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust, grant number 100064/Z/12/Z (DD). CC is part supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care West Midlands.

Disclaimer: This paper presents independent research and the views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Beasley R. Worldwide variation in prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and atopic eczema: ISAAC. Lancet 1998;351:1225–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butland BK, Strachan DP, Lewis S et al. Investigation into the increase in hay fever and eczema at age 16 observed between the 1958 and 1970 British birth cohorts. BMJ 1997;315:717–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warner JO, Kaliner MA, Crisci CD et al. Allergy practice worldwide—a report by the World Allergy Organization Specialty and Training Council. Allergy Clin Immunol Int 2006;18:4–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinmayr G, Forastiere F, Weiland SK et al. International variation in prevalence of rhinitis and its relationship with sensitisation to perennial and seasonal allergens. Eur Respir J 2008;32:1250–61. 10.1183/09031936.00157807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aït-Khaled N, Pearce N, Anderson HR et al. Global map of the prevalence of symptoms of rhinoconjunctivitis in children: The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Phase Three. Allergy 2009;64:123–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osborne NJ, Koplin JJ, Martin PE et al. Prevalence of challenge-proven IgE-mediated food allergy using population-based sampling and predetermined challenge criteria in infants. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;127:668–76.e2. 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.01.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agache I, Ryan D, Rodriguez MR et al. Allergy management in primary care across European countries—actual status. Allergy 2013;68:836–43. 10.1111/all.12150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morawetz DY, Hiscock H, Allen KJ et al. Management of food allergy: a survey of Australian paediatricians. J Paediatr Child Health 2014;50:432–7. 10.1111/jpc.12498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibbison B, Sheikh A, McShane P et al. Anaphylaxis admissions to UK critical care units between 2005 and 2009. Anaesthesia 2012;67:833–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2012.07159.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rudders SA, Banerji A, Vassallo MF et al. Trends in pediatric emergency department visits for food-induced anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;126:385–8. 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin RY, Anderson AS, Shah SN et al. Increasing anaphylaxis hospitalizations in the first 2 decades of life: New York State, 1990–2006. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2008;101:387–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poulos LM, Waters AM, Correll PK et al. Trends in hospitalizations for anaphylaxis, angioedema, and urticaria in Australia, 1993–1994 to 2004–2005. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;120:878–84. 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.07.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holgate ST. The epidemic of allergy and asthma. Nature 1999;402:2–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anandan C, Gupta R, Simpson CR et al. Epidemiology and disease burden from allergic disease in Scotland: analyses of national databases. J R Soc Med 2009;102:431–42. 10.1258/jrsm.2009.090027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Punekar YS, Sheikh A. Establishing the sequential progression of multiple allergic diagnoses in a UK birth cohort using the General Practice Research Database. Clin Exp Allergy 2009;39:1889–95. 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03366.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ninan TK, Russell G. Respiratory symptoms and atopy in Aberdeen schoolchildren: evidence from two surveys 25 years apart. BMJ 1992;304:873–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta R, Sheikh A, Strachan DP et al. Time trends in allergic disorders in the UK. Thorax 2007;62:91–6. 10.1136/thx.2004.038844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.House of Lords. Science and Technology Committee: Sixth report: allergy London: House of Lords, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 19.House of Commons Health Committee. The provision of allergy services: sixth report of Session 2003–04: Volume II: Oral and written evidence. House of Commons, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20. The Royal College of Physicians Working Party. Allergy : the unmet need. A blueprint for better patient care. London, UK: The Royal College of Physicians, 2003.

- 21. The Royal College of Physicians and Royal College of Pathologists Working Party. Allergy services: still not meeting the unmet need. London, UK: The Royal College of Physicians and Royal College of Pathologists, 2010.

- 22.Scottish Medical and Scientific Advisory Committee. Immunology and allergy services in Scotland. The Scottish Government, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sinnott L, Dudley-Southern R. Developing allergy services in the North West of England: lessons learnt. North West NHS Specialised Commissioning Group, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jutel M, Angier L, Palkonen S et al. Improving allergy management in the primary care network—a holistic approach. Allergy 2013;68:1362–9. 10.1111/all.12258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cummings AJ, Knibb RC, King RM et al. The psychosocial impact of food allergy and food hypersensitivity in children, adolescents and their families: a review. Allergy 2010;65:933–45. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02342.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akeson N, Worth A, Sheikh A. The psychosocial impact of anaphylaxis on young people and their parents. Clin Exp Allergy 2007;37: 1213–20. 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02758.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gupta R, Sheikh A, Strachan DP et al. Burden of allergic disease in the UK: secondary analyses of national databases. Clin Exp Allergy 2004;34:520–6. 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.1935.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lamb CE, Ratner PH, Johnson CE et al. Economic impact of workplace productivity losses due to allergic rhinitis compared with select medical conditions in the United States from an employer perspective. Curr Med Res Opin 2006;22:1203–10. 10.1185/030079906X112552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zuberbier T, Lötvall J, Simoens S et al. Economic burden of inadequate management of allergic diseases in the European Union: a GA2LEN review. Allergy 2014;69:1275–9. 10.1111/all.12470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hankin CS, Cox L, Bronstone A et al. Allergy immunotherapy: reduced health care costs in adults and children with allergic rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013;131:1084–91. 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.12.662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Griffin R, Gore C, Aston A, Hall S, Warner J, eds. Results of a 12 month children's integrated community allergy pathway project, ‘Itchy-Sneezy-Wheezy’. Clinical and experimental allergy. Hoboken (NJ): Wiley-Blackwell, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haahtela T, von Hertzen L, Makela M et al. Finnish Allergy Programme 2008–2018—time to act and change the course. Allergy 2008;63:634–45. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01712.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ewan P, Durham SR. NHS allergy services in the UK: proposals to improve allergy care. Clin Med 2002;2:122–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H et al. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015;13:141–6. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000100 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Isinkaye T, Gilbert S, Seddon P et al. How many paediatric referrals to an allergist could be managed by a general practitioner with special interest? Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2016;27:195–200. 10.1111/pai.12506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krishna MT, Knibb RC, Huissoon AP. Is there a role for telemedicine in adult allergy services? Clin Exp Allergy 2016;46:668–77. 10.1111/cea.12701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bousquet J, Schunemann HJ, Fonseca J et al. MACVIA-ARIA Sentinel NetworK for allergic rhinitis (MASK-rhinitis): the new generation guideline implementation. Allergy 2015;70:1372–92. 10.1111/all.12686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Conlon NP, Abramovitch A, Murray G et al. Allergy in Irish adults: a survey of referrals and outcomes at a major centre. Ir J Med Sci 2015;184:349–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chan YT, Ho HK, Lai CK et al. Allergy in Hong Kong: an unmet need in service provision and training. Hong Kong Med J 2015;21:52–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jones R, O'Connor A, Kaminski E. Patients’ experience of a regional allergy service. J Public Health Res 2013;2:e13 10.4081/jphr.2013.e13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Warner JO, Lloyd K. Shared learning for chronic conditions: a methodology for developing the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) care pathways for children with allergies. Arch Dis Child 2011;96(Suppl 2):i1–5. 10.1136/adc.2011.212654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levy ML, Walker S, Woods A et al. Service evaluation of a UK primary care-based allergy clinic: quality improvement report. Prim Care Respir J 2009;18:313–9. 10.4104/pcrj.2009.00042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Department of Health. Government response to House of Lords Science and Technology Committee report on Allergy: sixth report of session 2006–07. London, UK: Department of Health, 2007.

- 45.Department of Health Allergy Services Review Team. A review of services for allergy—the epidemiology, demand for and provision of treatment and effectiveness of clinical interventions. London: Department of Health, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 46.El-Shanawany TM, Arnold H, Carne E et al. Survey of clinical allergy services provided by clinical immunologists in the UK. J Clin Pathol 2005;58:1283–9. 10.1136/jcp.2005.027623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ryan D, Levy M, Morris A et al. Management of allergic problems in primary care: time for a rethink? Prim Care Respir J 2005;14:195–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Department of Health. Government response to the House of Commons Health Committee report on the Provision of Allergy Services: Sixth report of session 2003–04. Report. London, UK: Department of Health, 2005.

- 49.Levy ML, Price D, Zheng X et al. Inadequacies in UK primary care allergy services: national survey of current provisions and perceptions of need. Clin Exp Allergy 2004;34:518–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ewan PW. Provision of allergy care for optimal outcome in the UK. Br Med Bull 2000;56:1087–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brydon M. The effectiveness of a peripatetic allergy nurse practitioner service in managing atopic allergy in general practice—a pilot study. Clin Exp Allergy 1993;23:1037–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Haahtela T. A national allergy program 2008–2018. Drugs Today 2008;44(Suppl B):89–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Levy ML, Sheikh A, Walker S et al. Should UK allergy services focus on primary care? BMJ 2006;332:1347–8. 10.1136/bmj.332.7554.1347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Conlon NP, Edgar JDM. Adherence to best practice guidelines in chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) improves patient outcome. Eur J Dermatol 2014;24:385–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blaiss MS. Cognitive, social, and economic costs of allergic rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Proc 2000;21:7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hon KL, Pong NH, Poon TCW et al. Quality of life and psychosocial issues are important outcome measures in eczema treatment. J Dermatolog Treat 2015;26:83–9. 10.3109/09546634.2013.873762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fox M, Mugford M, Voordouw J et al. Health sector costs of self-reported food allergy in Europe: a patient-based cost of illness study. Eur J Public Health 2013;23:757–62. 10.1093/eurpub/ckt010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gupta R, Holdford D, Bilaver L et al. The economic impact of childhood food allergy in the United States. JAMA Pediatr 2013;167:1026–31. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jones RB, Hewson P, Kaminski ER. Referrals to a regional allergy clinic—an eleven year audit. BMC Public Health 2010;10:790 10.1186/1471-2458-10-790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.O'Neill M, Karelas GD, Feller DJ et al. The HIV workforce in New York State: does patient volume correlate with quality? Clin Infect Dis 2015;61:1871–7. 10.1093/cid/civ719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. EAACI knowledge exam 2016 (cited 11 October 2016). http://www.eaaci.org/activities/eaaci-exam/upcoming-exam.html

- 62.Haahtela T, Tuomisto LE, Pietinalho A et al. A 10 year asthma programme in Finland: major change for the better. Thorax 2006;61:663–70. 10.1136/thx.2005.055699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kinnula VL, Vasankari T, Kontula E et al. The 10-year COPD programme in Finland: effects on quality of diagnosis, smoking, prevalence, hospital admissions and mortality. Prim Care Respir J 2011;20:178–83. 10.4104/pcrj.2011.00024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lodrup Carlsen KC, Haahtela T, Carlsen KH et al. Integrated allergy and asthma prevention and care: report of the MeDALL/AIRWAYS ICPs meeting at the ministry of health and care services, Oslo, Norway. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2015;167:57–64. 10.1159/000431359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sheffield Childrens NHS Foundation Trust. Itchy, Sneezy, Wheezy clinic to combat allergies 2014 [9 November 2015]. http://www.sheffieldchildrens.nhs.uk/news/itchy-sneezy-wheezy-clinic-to-combat-allergies.htm

- 66.Taha S, Patel N, Gore C. G388 ‘Itchy-Sneezy-Wheezy’ survey: comparison of GP referral reasons to diagnoses on first allergy clinic letters. Arch Dis Child 2014;99(Suppl 1):A161–A. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Patel N, Warner J, Gore C, eds. Itchy ‘sneezy’ wheezy survey: how do referral reasons to allergy clinic compare to diagnoses made at first allergy clinic visit? Clinical and experimental allergy. Hoboken (NJ): Wiley-Blackwell, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-012647supp_PRISMA-checklist.pdf (335.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-012647supp_Search-Strategy.pdf (7.8KB, pdf)