Abstract

Metformin-associated lactic acidosis (MALA) is a rare but life-threatening complication. We report a case of MALA in a man aged 71 years who was treated with continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT). The patient was brought to the hospital for prolonged and gradual worsening gastrointestinal symptoms. Although he received intravenous treatment, he developed catecholamine-resistant shock, and blood gas analysis revealed lactic acidosis. Bicarbonate and antibiotics for possible sepsis were initiated, but with no clear benefit. Owing to haemodynamic instability with metabolic acidosis, urgent CRRT was given: it was immediately effective in reducing lactate levels; pH values completely normalised within 18 hours, and he was stabilised. MALA sometimes presents with non-specific symptoms, and is important to consider when treating unexplainable metabolic acidosis. In severe cases, CRRT has potential merit, particularly in haemodynamically unstable patients. It is important to be familiar with MALA as a medical emergency, even for emergency physicians.

Background

Metformin, a biguanide antihyperglycaemic drug, has been widely prescribed for type 2 diabetes mellitus due to its effect in decreasing insulin resistance. Although it is an effective, less expensive and relatively safe drug, it is also known to cause lactic acidosis.1 Metformin-associated lactic acidosis (MALA) is an extremely rare complication, but the mortality rate approaches 30–50%.1 2 Owing to the rarity of MALA, a standard treatment strategy has not been established. Since MALA is characterised by severe acidaemia accompanying catecholamine-resistant circulatory failure, continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) has been suggested as a treatment method. Despite potential advantages, CRRT for the treatment of MALA is poorly documented, with only a few case reports available.2–5 This report describes a case of MALA, which is mimicking septic shock requiring CRRT with favourable outcome.

Case presentation

A man aged 71 years with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and alcoholic liver cirrhosis (Child-Pugh B classification) was admitted to this hospital because of appetite loss and vomiting. He was taking metformin 500 mg/day. The patient was in his usual health until ∼2 weeks before admission, when he reportedly began to feel unwell, with nausea and vomiting. Over the subsequent 4 days, his oral intake decreased and he visited the local clinic where he received supportive measures with a diagnosis of enterocolitis. Approximately 18 hours before presentation, he developed increasing abdominal pain associated with vomiting and shortness of breath. He was brought to our hospital after 2 hours of haematemesis.

Investigations

On arrival, the patient appeared uncomfortable but was alert. Vital signs were as follows: blood pressure, 105/45 mm Hg; pulse, 102 bpm; temperature, 35.9°C; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min; oxygen saturation, 100% on ambient air. The abdomen was soft, without distension, rebound tenderness or guarding. The skin was cool, but the remainder of the general examination was normal. Laboratory investigations revealed the following: white cell count, 28 860/μL; haemoglobin, 9.0 g/dL; platelets, 18.3×104/μL; total bilirubin, 1.5 mg/dL; aspartate aminotransferase, 30 IU/dL; alanine transaminase, 25 IU/dL, blood urea nitrogen, 33 mg/dL; creatinine, 1.52 mg/dL; estimated glomerular filtration rate, 36.1 mL/min/1.73 m2; C reactive protein, 1.01 mg/dL; prothrombin 24.0 s (prothrombin international normalised ratio, 1.99). Although marked leucocytosis and renal insufficiency emerged, other values showed almost no interval change compared with his baseline. His usual renal function was following: blood urea nitrogen, 16 mg/dL; creatinine, 0.95 mg/dL; estimated glomerular filtration rate, 60.4 mL/min/1.73 m2, and he had mild albuminuria. He was admitted to the general ward and received intravenous treatment with increased acetated Ringer's solution with 1% glucose, for possible enterocolitis and dehydration. Within 8 hours of admission, he developed tachypnoea, increased somnolence and hypotension (59/33 mm Hg); blood sampling showed severe anion gap increased lactic acidosis with a pH of 7.06, bicarbonate of 7.4 mmol/L, base excess of −21.2 mmol/L, lactate >20.0 mmol/L and anion gap of 25.6 mEq/L.

Differential diagnosis

Septic shock

Metformin-associated lactic acidosis (MALA)

Treatment

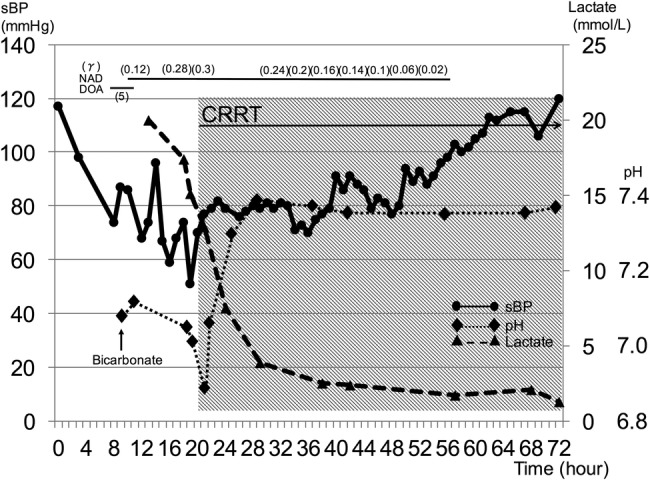

He was moved to the intensive care unit and intubated; bicarbonate and norepinephrine were infused for metabolic acidosis and severe hypotension. CT of the whole body showed liver cirrhosis with mild ascites but no evidence of infection. He received upper endoscopy with suspicion of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, but it showed an oesophageal tear without active bleeding. It was unlikely to become the cause of refractory shock. After collecting two sets of blood cultures, meropenem and daptomycin were administered because of concern for sepsis. Aggressive treatment with fluids, vasopressors and bicarbonate was continued, but with no clear benefit. Owing to haemodynamic instability with metabolic acidosis, urgent CRRT (continuous haemodiafiltration, with a dialysate rate of 2300 mL/hour) was given: it was immediately effective in reducing lactate levels; pH values completely normalised within 18 hours, and he was stabilised (figure 1). Antibiotics were discontinued with negative blood cultures after 7 hospital days.

Figure 1.

The clinical time course of systolic blood pressure, lactate level and pH. Severe acidaemia accompanying vasopressor-resistant hypotension dramatically resolved with continuous renal replacement therapy and the patient was stabilised within 16 hours. sBP, systolic blood pressure; NAD, noradrenalin; DOA, dopamine; CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy.

Outcome and follow-up

He required continuing CRRT and a small amount of norepinephrine administration for fluid management because of his liver cirrhosis; these were discontinued and he was extubated on the 10th hospitalised day and moved back to the general ward on the 14th day.

Discussion

In the setting of chronic metformin use and lactic acidosis accumulation (MALA), the most common symptoms are gastrointestinal, including nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea, followed by altered mental status, shortness of breath and hypotension, but these findings are non-specific.6 In the emergency setting, it is sometimes difficult to obtain a detailed medical history due to altered mental status. As described previously, multiple case series report high mortality rates with MALA,1 2 and we must not skimp on efforts to perform blood gas analysis for accurate determination of acid–base status in patients who show gastrointestinal symptoms of uncertain cause. The development of MALA is most likely due to the presence of concomitant risk factors, rather than metformin alone.7 Clinically significant lactic acid accumulation almost always occurs in the presence of comorbid conditions, such as renal insufficiency, concurrent liver disease or alcohol abuse, heart failure, decreased tissue perfusion or haemodynamic instability and hypoxic states or serious acute illness. Additionally, it has been reported that cardiogenic or hypovolaemic shock, trauma and sepsis are the most common cause of lactic acidosis.7 Since plasma metformin concentration analysis is not usually available, it is particularly important to suspect MALA in patients with metabolic acidosis (eg, pH <7.2) with elevated lactate (eg, >5 mmol/L) in any setting.5 Although there was controversy regarding the relationship between the value of metformin plasma concentration and the severity of lactic acidosis,7 recent studies suggested that metformin accumulation contributes to the pathogenesis and prognosis of lactic acidosis.8 Routine assessment of metformin plasma concentration is not easily available in all laboratories, but it has been reported that plasma metformin concentration measured in the emergency room could ensure the correct diagnosis.9

Concerning treatment, cardiorespiratory supportive care is performed based on the differential diagnosis of metabolic acidosis. Hypotension is initially treated with intravenous fluids followed by vasopressors if needed; however, MALA is difficult to differentiate from sepsis, especially in severe cases.4 In the present case, we had no choice but to treat the patient for septic shock. For patients with severe metformin poisoning require extracorporeal removal, haemodialysis is the preferred approach if the haemodynamics are adequate.10 Although the evidence is limited, the clinical efficacy of CRRT is noted in case reports.2–5 The clearance of drugs by CRRT may be less than that generally reported to occur with conventional haemodialysis, but it is worth considering in patients who are too haemodynamically unstable to tolerate haemodialysis.10

Owing to its infrequency and heterogeneity, large randomised trials for the management of MALA are hardly expected; retrospective series and case reports are needed.

In conclusion, we report a case of MALA, a rare complication of metformin therapy, with CRRT. In the absence of acute overdose, MALA rarely develops in patients without comorbidities such as renal or hepatic insufficiency or acute infection.4 Clinicians must be knowledgeable about the general contraindications of metformin. Additionally, patient education for MALA is also needed. Finally, as a result of the renewed and widespread use of metformin, it is important to correctly understand MALA as a medical emergency, even for emergency physicians.

Learning points.

Metformin-associated lactic acidosis (MALA) sometimes presents with non-specific symptoms, and it is important to consider MALA and provide empiric treatment when examining patients with unexplained metabolic acidosis.

In severe cases of MALA, renal replacement therapy can be considered and continuous renal replacement therapy has potential merit, especially with haemodynamically unstable patients.

There is a need for epidemiological information and the provision of physician education to avoid ‘preventable MALA’.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded in part by a grant under the category, ‘Mie University Hospital Seed Grant Program 2015’, from Mie University Hospital (to HI and KS) and ‘JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 16K20384’ (to KS). The authors thank all the colleagues of the emergency and critical care centre and department of nephrology, Mie University Hospital.

Footnotes

Contributors: KS and AN collected the data and drafted the manuscript. KS, AN and HI were involved in the treatment of the patient. NK revised and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Nguyen HL, Concepcion L. Metformin intoxication requiring dialysis. Hemodial Int 2011;15(Suppl 1):S68–71. 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2011.00605.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guo PY, Storsley LJ, Finkle SN. Severe lactic acidosis treated with prolonged hemodialysis: recovery after massive overdose of metformin. Semin Dial 2006;19:80–3. 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2006.00123.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moioli A, Maresca B, Manzione A et al. Metformin associated lactic (MALA) acidosis clinical profiling and management. J Nephrol 2016;29:783–9. 10.1007/s40620-016-0267-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dichtwald S, Weinbroum AA, Sorkine P et al. Metformin-associated lactic acidosis following acute kidney injury. Efficacious treatment with continuous renal replacement therapy. Diabet Med 2012;29:245–50. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03474.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keller G, Cour M, Hernu R et al. Management of metformin-associated lactic acidosis by continuous renal replacement therapy. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e23200 10.1371/journal.pone.0023200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Uppot RN, Lewandrowski KB. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 23–2013. A 54-year-old woman with abdominal pain, vomiting, and confusion. N Engl J Med 2013;369:374–82. 10.1056/NEJMcpc1208154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang W, Castelino RL, Peterson GM. Lactic acidosis and the relationship with metformin usage: case reports. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e4998 10.1097/MD.0000000000004998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Visconti L, Cernaro V, Ferrara D et al. Metformin-related lactic acidosis: is it a myth or an understimated reality? Ren Fail 2016;38:1560–5. 10.1080/0886022X.2016.1216723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boucaud-Maitre D, Ropers J, Porokhov B et al. Lactic acidosis: relationship between metformin levels, lactate concentration and mortality. Diabet Med 2016;33:1536–43. 10.1111/dme.13098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calello DP, Liu KD, Wiegand TJ et al. , Extracorporeal Treatments in Poisoning Workgroup. Extracorporeal treatment for metformin poisoning: systematic review and recommendations from the extracorporeal treatments in poisoning workgroup. Crit Care Med 2015;43:1716–30. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]