Significance

Autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) comprise a heterogeneous set of neurodevelopmental disorders. Although hundreds of genes have now been identified to be associated with ASD, genetic factors cannot fully explain ASD’s incidence. The early environment is now known to be pivotal in ASD’s etiology too. In the face of this complexity, one aspect of ASD has stood out constantly as a causative biological factor: the sex difference. Approximately 80% of the children diagnosed are boys. This current set of experiments tests, in an animal model, the “three-hit theory of autism,” which states that interactions among (i) being male, (ii) suffering early (especially, prenatal/immunological) stress, and (iii) having certain genetic mutations will predispose to an ASD diagnosis.

Keywords: maternal immune activation, prenatal stress, sex differences, Cntnap2, autism

Abstract

The male bias in the incidence of autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) is one of the most notable characteristics of this group of neurodevelopmental disorders. The etiology of this sex bias is far from known, but pivotal for understanding the etiology of ASDs in general. Here we investigate whether a “three-hit” (genetic load × environmental factor × sex) theory of autism may help explain the male predominance. We found that LPS-induced maternal immune activation caused male-specific deficits in certain social responses in the contactin-associated protein-like 2 (Cntnap2) mouse model for ASD. The three “hits” had cumulative effects on ultrasonic vocalizations at postnatal day 3. Hits synergistically affected social recognition in adulthood: only mice exposed to all three hits showed deficits in this aspect of social behavior. In brains of the same mice we found a significant three-way interaction on corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor-1 (Crhr1) gene expression, in the left hippocampus specifically, which co-occurred with epigenetic alterations in histone H3 N-terminal lysine 4 trimethylation (H3K4me3) over the Crhr1 promoter. Although it is highly likely that multiple (synergistic) interactions may be at work, change in the expression of genes in the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal/stress system (e.g., Crhr1) is one of them. The data provide proof-of-principle that genetic and environmental factors interact to cause sex-specific effects that may help explain the male bias in ASD incidence.

Autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) comprise a heterogeneous group of neurodevelopmental disorders. The core symptoms of ASD are deficits in social communication and social interactions (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders V) and one of the most noticeable biological constants in this group of disorders is the sex difference: ∼80% of the children diagnosed with an ASD are boys (1). Many genes have been implicated in the etiologies underlying ASD in humans and ASD-like behavior in animal models. Some of these genes are located on the sex chromosomes and many of these genes may be able to affect other sex-chromosomal genes or may otherwise indirectly lead to sex-specific effects (reviewed in ref. 2). However, it seems unlikely that these genes can account for the full sex bias in incidence and it is becoming increasingly clear that environmental factors play a very important role as well (3), and that these factors can interact with one another (2, 4). Moreover, prenatal testosterone (an indirect genetic factor) affects human behavior (5, 6) and may increase the risk to develop an ASD (7).

Although today it is commonly proposed that many neurodevelopmental disorders result from interactions between “nature” and “nurture,” studies investigating the gene–environment interaction in the development of ASD are scarce.

In this study we tested whether an interaction between an ASD-related genetic mutation and an environmental factor may be able to explain some of the sex-specific phenotypes of ASD in a mouse model. We used the contactin-associated protein-like 2 (Cntnap2) knockout mouse model for ASD. A homozygous mutation of CNTNAP2 in humans leads to an ASD in approximately two-thirds of the cases (8), and CNTNAP2 is reported to be androgen-sensitive, at least in breast and prostate cancer tissue (9, 10). One of the most well-known environmental factors that may play a role in the etiology of ASD is early stress through maternal immune activation (MIA) (11, 12), especially early during pregnancy (13). Animal models support the notion that MIA plays a pivotal role in ASD’s etiology because experimentally induced MIA leads to deficits that are the key features in ASD: social communication and interactions (14, 15).

Thus, we tested whether MIA may be able to account for some of the sex-specific phenotypes of ASD in a genetic ASD mouse model. To study this “three hit” hypothesis of autism (16), we used the Cntnap2 mouse model (17) in which we induced MIA in half of the subjects and tested Cntnap2−/− and Cntnap2+/+ male and female littermates on social behavior [ultrasonic vocalizations (USVs) during a maternal separation paradigm and social recognition in adulthood], one of the hallmarks of ASD. Additionally, we investigated motor activity and anxiety-like behavior, as hyperactivity and anxiety are common comorbidities in individuals diagnosed with an ASD (18, 19).

In the same animals, we measured mRNAs related to the stress response-regulating neuropeptide corticotropin-releasing hormone (20, 21) (CRH). At least in primates, stress-induced maternal hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA)-axis activation increases CRH levels in the placenta, which leads to increased circulating CRH in the fetus, which can affect the developing hippocampus, likely by activating CRH receptors (22). In rodents, placental CRH mRNA has also been reported (23, 24). It has been shown that neurogenesis, neuron functioning, and cell survival in the hippocampus are affected by MIA (25–27). There are two subtypes of CRH receptors, CRH receptor 1 and 2 (CRHR1 and CRHR2), the first one being the predominant subtype in the mouse hippocampus. Furthermore, increased expression of Crhr1 (but not Crhr2) in response to peripubertal stress in rats was shown to be associated with social deficits, and these effects were prevented by treatment with a CRHR1 antagonist (28). Interestingly, in light of ASD’s strong male bias in incidence, prenatal stress affects the expression of Crhr1 in the paraventricular nucleus in a sex-specific way; only males show Crhr1 up-regulation (29). Prolonged activation of CRHR1 in the hippocampus as a result of early stress affects the structure, synaptic function, and cognition (30, 31), but we are not aware of any studies that have investigated the sex-specific effect of prenatal (immunological) stress on CRH or its receptors in the hippocampus. Because ASD is associated with changes in lateralization [behavioral study (32), MRI studies (33, 34), magnetoencephalography study (35), and references in these studies], and many genes are asymmetrically expressed in the rodent hippocampus (36), we performed Crh, Crhr1, Crhr2, and Crhbp (corticotropin-releasing factor-binding protein) mRNA gene-expression assays on the two hemispheres separately. Because we found the strongest effects on Crhr1 mRNA expression in the left hippocampus, we then continued to investigate histone modifications on the promoter area of the Crhr1 gene in the left hippocampus. The promoter area chosen is thought to bind SRY (re: sex) and NF-κB (re: stress). Because tissue for gene-expression assays originated from the mice used in the behavioral tests, we could investigate the correlates between the behavioral and molecular measures.

Results

Because the three-hit hypothesis revolves around the synergistic effects of several factors, whereby factors that have low or no effect independently can have significant effects when combined, we present the data in a categorical fashion (four categories: zero hits to three hits). The results of the statistical models can be found in Dataset S1. Because the individual hits might give us additional information, we also present the data on the individual hits and their interactions; their statistics and figures are presented in SI Methods.

Ultrasonic Vocalizations.

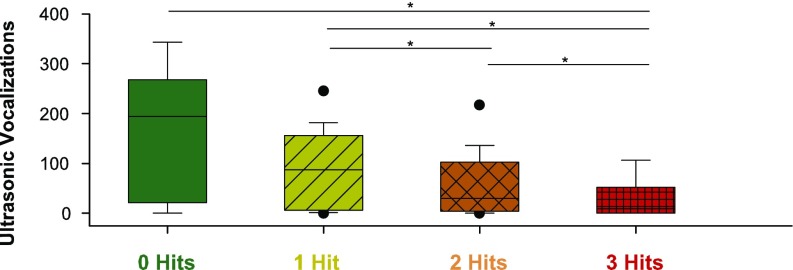

We investigated social communication by means of the number of ultrasonic vocalizations during a 5-min maternal-separation paradigm. Both male and female pups typically emit these calls, which elicit maternal retrieval of the pups. We found a significant effect of number of hits the animals were exposed to on the number of vocalizations on postnatal day (PD) 3, the day featuring the highest amount of calling (Fig. 1). The zero-hit animals (no-MIA female WTs) vocalized significantly more than the three-hit mice (MIA male KOs). In the monotonic increase, animals exposed to one-hit (MIA female WTs or no-MIA male WTs or no-MIA female KOs) vocalized significantly more than animals exposed to two or three hits. Finally, animals exposed to two hits vocalized significantly more than animals exposed to three hits.

Fig. 1.

Box-plot of number of USV emitted by pups at PD3. Number of USV significantly differed between the categories (χ2 = 21.585, df = 3, P < 0.001). Zero-hit mice vocalized more than the three-hit mice (P = 0.009). One-hit mice vocalized more than both the two-hit (P = 0.038) and the three-hit mice (P < 0.001). Two-hit mice vocalized more than three-hit mice (P = 0.017). Outliers are depicted as dots. Boxes represent 25th and 75th percentiles, whiskers are 5th and 95th percentiles. Horizontal line is the median. *P < 0.05.

Of the different hits, MIA had the largest effect and genotype, although still significant, had the lowest effect on number of vocalizations (Fig. S1).

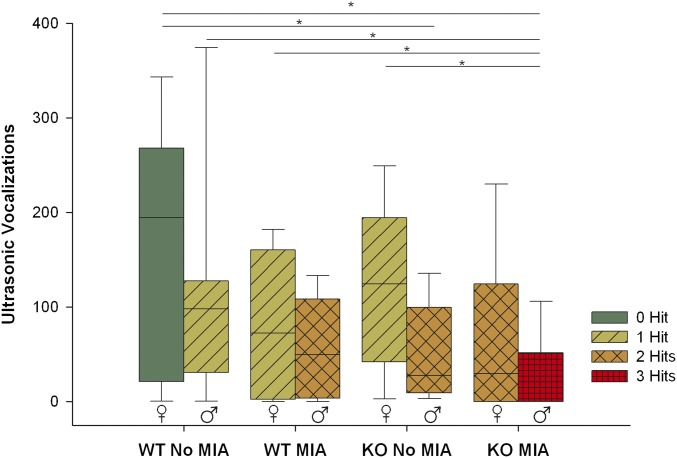

Fig. S1.

Box-plot of number of USVs emitted by pups at PD3 in the eight experimental groups. NS mice vocalized more than MIA mice (χ2 = 8.406, df = 1, P = 0.004). Females vocalized more than males (χ2 = 7.764, df = 1, P = 0.005). WT mice vocalized more than KO mice (χ2 = 4.759, df = 1, P = 0.029). No significant interaction effects were present. Boxes represent 25th and 75th percentiles, whiskers are the 5th and 95th percentiles. Horizontal line is the median. *P < 0.05.

Social Recognition.

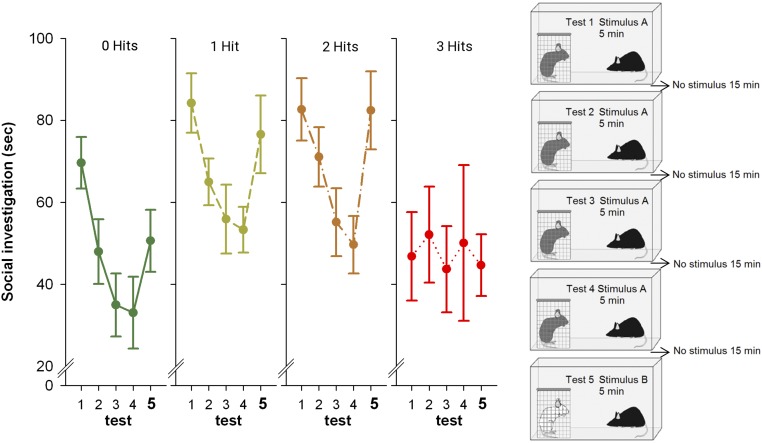

We tested the effects of the three hits on social recognition, which can be defined by reduced time spent investigating a familiar conspecific as a result of social habituation, and subsequent reinstatement of investigation when a novel intruder is introduced (dishabituation). When considering all five trials, we found a significant effect of the number of hits on social recognition (Fig. 2 and Dataset S1). Because habituation may simply reflect loss of the interest in the testing environment, the dishabituation phase (difference in social interest between the fourth and the fifth trial) may be a more important measure for true social recognition. We found significant differences between the categories because the three-hit mice show deficits in both habituation (tests 1–4) and dishabituation (tests 4–5). Strikingly, the three-hit mice were the only experimental group that showed no changes in social behaviors over any of the trials (Fig. 2). The two-hit mice tended to show somewhat increased social recognition: they showed a nonsignificant tendency to show increased habituation compared with the zero-hit mice and a nonsignificant increased dishabituation compared with the zero-hit mice. The two-hit mice were the only category of mice that performed significantly better than the three-hit category (P = 0.045).

Fig. 2.

Social recognition. Seconds socially investigating a conspecific [same conspecific in tests 1–4; novel conspecific in test 5 (marked bold to emphasize that a new stimulus mouse was introduced)]. Social recognition significantly differed between the three-hit categories [F(3, 58) = 2.820, P = 0.047]. Post hoc planned comparisons showed that habituation to the same stimulus conspecific (tests 1–4) was significant in the zero-hit [F(3, 24) = 9.611, P < 0.001], one-hit [F(3, 75) = 7.995, P < 0.001], and two-hit [F(3, 60) = 7.509, P < 0.001], but not in the three-hit category. Dishabituation was significant in the zero-hit category [F(1, 8) = 7.598, P = 0.025], borderline significant in the one-hit category [F(1, 25) = 3.630, P = 0.068], significant in the two-hit category [F(1, 21) = 21.504, P < 0.001], and not significant in the three-hit category. Mean and SEMs are shown.

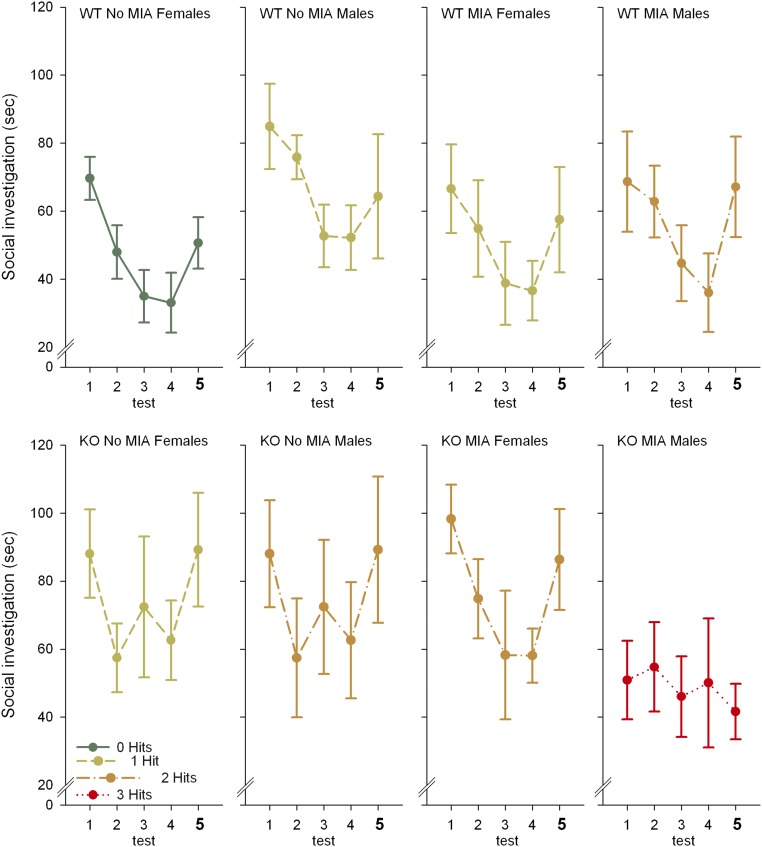

Looking at the individual hits, we found that genotype had an overall negative effect on social recognition, caused by deficits in dishabituation. Additionally, a significant sex × MIA interaction effect was present, as MIA caused deficits in social interaction in males only. This interaction effect was only present in the KOs, not in the WTs, and was again mainly caused by differences in dishabituation (Fig. S2).

Fig. S2.

Seconds socially investigating a conspecific [same conspecific in tests 1–4; novel conspecific in test 5 (marked in bold)] in the eight experimental groups. KOs show deficits in social recognition compared with WTs [F(1, 58) = 4.404, P = 0.040]. Neither sex nor MIA showed an overall main effect. A significant interaction effect of sex and MIA is present [F(1, 55) = 4.635, P = 0.036] because MIA causes deficits in social recognition in males [F(1, 28) = 6.074], but not in females. This interaction effect is only present in the KOs [F(1, 24) = 6.023, P = 0.022], not in the WTs. Overall there is no significant interaction effect between MIA and genotype and between sex and genotype. The significant effects are mainly driven through deficits in dishabituation (tests 4–5). There are no significant main or interaction effects of sex, MIA, or genotype on habituation (tests 1–4). Dishabituation, however, is impaired in KOs [tests 4–5: F(1, 59) = 6.225, P = 0.015]. There is a trend for an interaction effect between MIA and sex [F(1, 56) = 2.884, P = 0.095], which is significant when only KOs are considered [F(1, 25) = 4.527, P = 0.043] because MIA only significantly causes impairments in KO males [F(1, 11) = 7.932, P = 0.017]. Post hoc planned comparisons showed that habituation was significant in the no-MIA WT females [F(3, 24) = 9.611, P < 0.001], in the no-MIA WT males [F(3, 27) = 5.839, P = 0.003], in the MIA WT males [F(3, 21) = 5.875, P = 0.004], and showed a trend in the no-MIA KO females [F(3, 24) = 2.375, P = 0.095], and is not significant in the no-MIA KO males, the MIA WT females, the MIA KO females, and the MIA KO males. Dishabituation was significant in the no-MIA WT females [F(1, 8) = 7.598, P = 0.025], the no-MIA KO males [F(1, 6) = 10.055, P = 0.019], the MIA KO females [F(1, 6) = 8.525, P = 0.027], and showed a trend in the no-MIA KO females [F(1, 8) = 3.909, P = 0.083] and in the MIA WT males [F(1, 7) = 5.404, P = 0.053], and is not significant in the no-MIA WR males, the MIA WT females, and the MIA KO males. Mean and SEMs are shown.

Open Field.

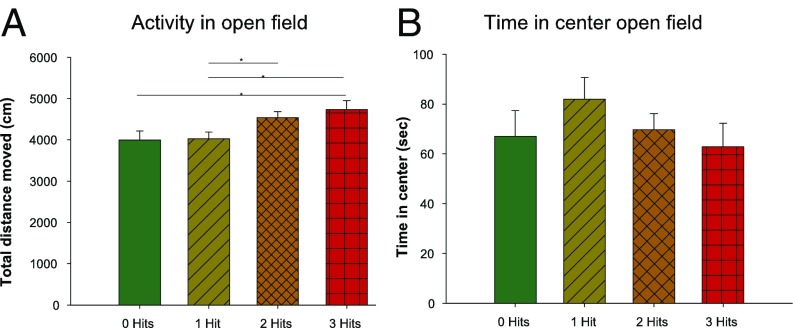

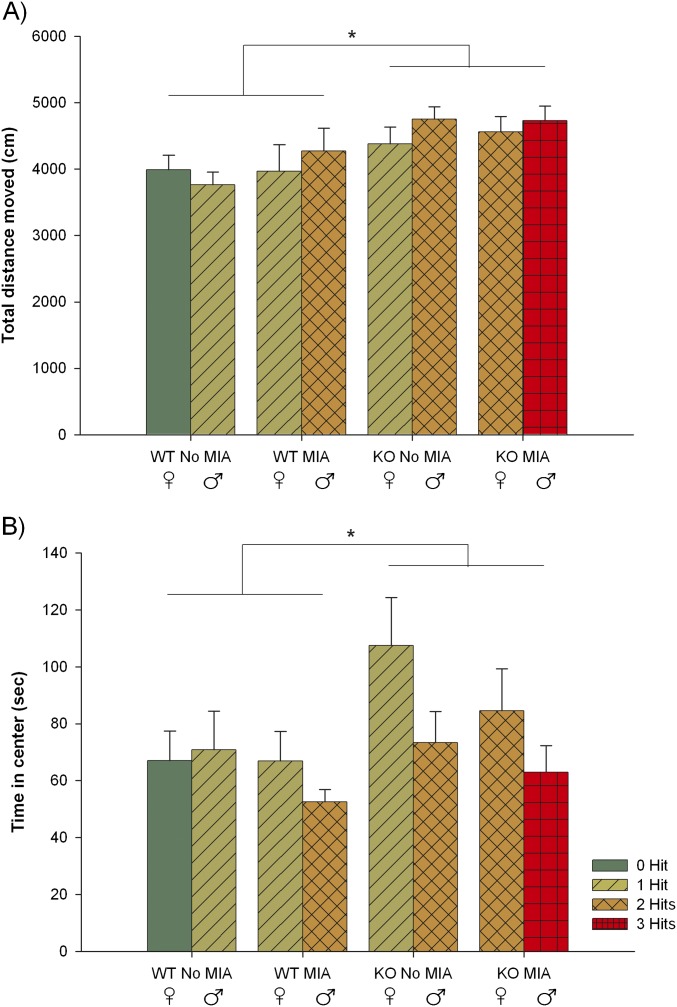

Because ASD symptoms often co-occur with hyperactivity and anxiety, and to investigate whether increased activity or anxiety could account for the differences observed in the social-recognition test, we measured hyperactivity and anxiety in an open-field apparatus. We found that there are significant differences between groups in the distance traveled during the 10 min of free exploration in the open-field arena (Fig. 3A). The three-hit mice covered greater distance than the zero-hit and the one-hit mice. The two-hit mice covered more distance than the one-hit mice. No significant differences were found in time spent in the middle of the apparatus, a measure for anxiety (Fig. 3B). Looking at the individual hits, we found that only genotype resulted in significant differences, with WT mice covering less distance and spending less time in the middle of the apparatus than KO mice (Fig. S3).

Fig. 3.

Open field. (A) Bar graph of the total distance (centimeters) moved during a 10-min open field. Total distance moved significantly differed between the categories [F(3, 64) = 3.262, P = 0.027]. Zero-hit mice moved less than three-hit mice (P = 0.049), one-hit mice moved less than two-hit mice (P = 0.020) and three-hit mice (P = 0.026). (B) Bar graph of the time spent in the middle of the open field (seconds). No significant differences between the categories were found. Mean and SEMs are shown. *P < 0.05.

Fig. S3.

Open field. (A) Total distance moved in the eight experimental groups. KO mice covered a greater distance compared with WT mice [F(1, 64) = 11.642, P = 0.001]. MIA and sex had no effect on the distance moved, nor were any interaction effects present. (B) Time spent in center in the eight experimental groups. KO mice spent longer periods of time in the center of the open-field apparatus than WT [F(1, 64) = 4.058, P = 0.048]. Males tended to spend less time in the middle of the apparatus [F(1, 31) =3.758, P = 0.057]. MIA had no significant effect on time spent in the middle, nor were any interaction effects present. Means and SEMs are displayed. *P < 0.05.

Gene Expression.

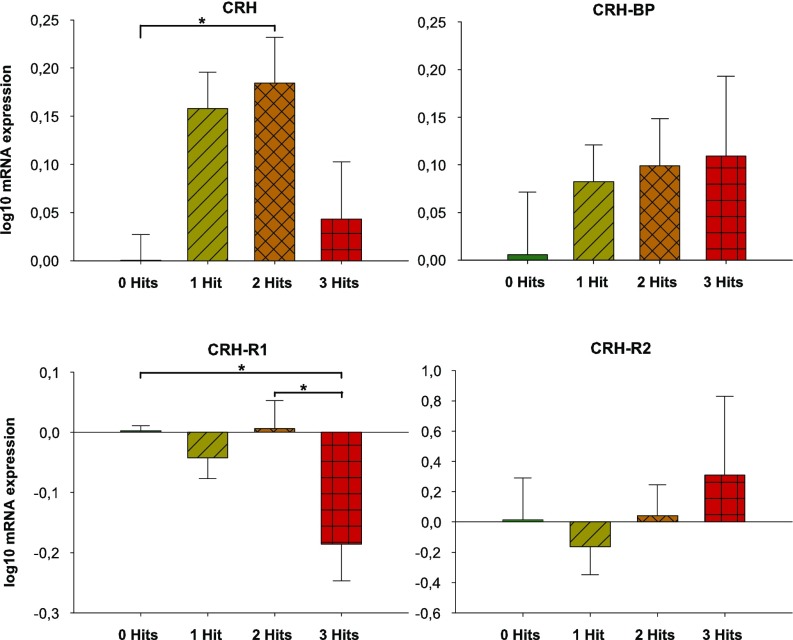

Next, in the same animals, we investigated the Crh system in the hippocampus. In the left hippocampus we found a trend for the effect of the number of hits on Crh expression (Fig. 4). The two-hit category expressed significantly more Crh mRNA than the zero-hit category. To investigate whether Crh expression was related to social recognition, we checked for a correlation between the total time spent sniffing the stimulus during the habituation phase (trials 1–4) and Crh expression. We found a positive correlation between Crh mRNA and habituation (Pearson’s r = 0.335, P = 0.040). The correlation is absent during the last trial (trial 5) of the social-recognition test. No correlations between Crh mRNA expression in the hippocampus and the number of USVs emitted or anxiety and mobility measures were found.

Fig. 4.

Bar graphs of log-transformed mRNA expression in adult mice. There was a trend for an overall effect of number of hits on Crh expression [F(3, 55) = 2.371, P = 0.080] and on Crhr1 expression [F(3, 53) = 2.532, P = 0.067]. Post hoc tests showed that the two-hit category expressed significantly more Crh mRNA than the zero-hit category (P = 0.028) and that three-hit category expressed significantly less Crhr1 mRNA than the zero-hit group (P = 0.043) and the two-hit group (P = 0.012). No significant effects of number of hits on Crhbp and Crhr2 were found. *P < 0.05.

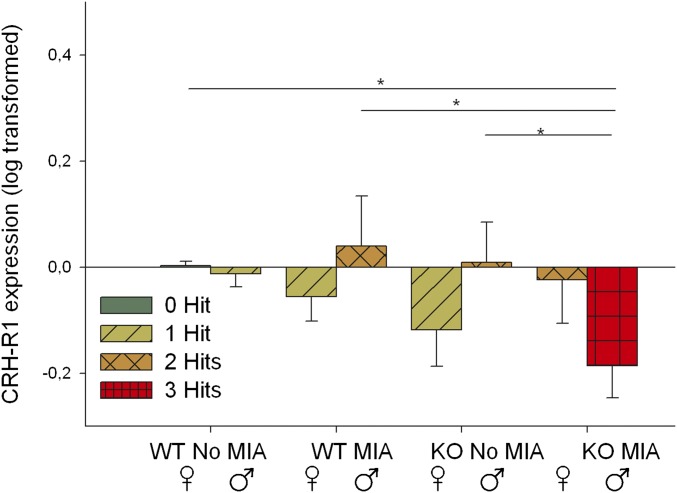

We also found a trend for the effect of the number of hits on Crhr1 expression in the left hippocampus (Fig. 4). Both the two-hit and the three-hit category expressed significantly less Crhr1 mRNA than the zero-hit category. Looking at individual hits, we found that in the left hippocampus Crhr1 shows a significant three-way interaction. Only in the KOs (not the WTs) there is a trend for a sex × MIA interaction effect: MIA tends to affect males, but does not affect females (Fig. S4). Additionally, we found a positive and significant correlation between Crhr1 expression and social behavior over the five trials (Pearson’s r = 0.347, P = 0.035). During the habituation phase (trials 1–4), this correlation with Crhr1 mRNA is significant (Pearson’s r = 0.376, P = 0.022). The correlation is absent during the last trial (trial 5) of the social-recognition test. No correlation between Crhr1 mRNA expression in the hippocampus and the number of USVs emitted or anxiety and mobility measures were found.

Fig. S4.

Bar graphs of log-transformed Crhr1 mRNA expression in adult mice in the eight experimental groups. There is a significant three-way interaction between sex, MIA, and genotype [F(1, 49) = 4.741, P = 0.034]. In the KOs there is a trend for a sex × MIA interaction effect [F(1, 25) = 3.810, P = 0.062], whereas this effect is not present in the WTs. Similarly, in the MIA group there is a trend for a genotype × MIA interaction effect [F(1, 25) = 3.027, P = 0.094], whereas this is not present in the no stress group. Finally, in males there is a trend for a genotype × MIA interaction effect [F(1, 24) = 3.164, P = 0.088], whereas this is not present in females. Post hoc tests showed that KO MIA males expressed lower levels of Crhr1 than the KO no-MIA males (P = 0.043), WT MIA males (P = 0.018), and than the WT no-MIA females (P = 0.047). The individual factors (sex, MIA, or genotype; main effects) do not affect Crhr1 mRNA expression.*P < 0.05.

No effects were found on Crhbp or Crhr2 expression, nor did we find effects in the right hippocampus.

Histone N-Terminus Modifications.

Histone modifications can be induced by environmental factors, such as stress (37). For potential explanations of the mRNA data, we studied alterations of lysine modifications on the histone H3 N terminus, as well as global acetylation levels of H3 over the Crhr1 promoter. We chose a primer pair that amplifies a genomic region −560 to −461 bp relative to Crhr1’s transcriptional start site, which contains the promoter area that, according to TFSEARCH prediction (www.cbrc.jp/), is very likely to include transcription factor binding sites for testis-determining SRY, as well as for the cellular stress-related signal NF-κB1, and may therefore be especially important in the underlying mechanisms of sex-specific effects of gene–environment interactions.

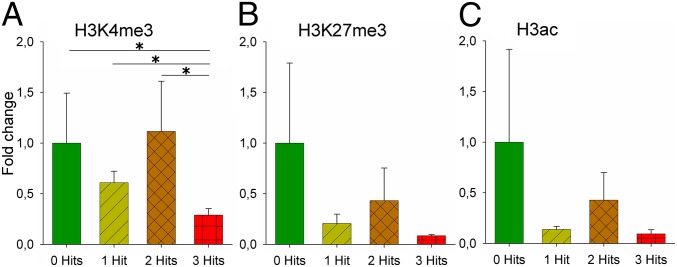

The number of hits significantly affected H3 trimethylation on lysine 4 (H3K4me3) at the promoter area of Crhr1 in the left hippocampus (Fig. 5). Post hoc tests showed that the three-hit category had the lowest levels of H3K4me3. H3K4me3 is associated with transcriptionally active genes. The low levels of H3K4me3 in the three-hit category can therefore (partly) explain the low levels of Crhr1 mRNA in the same group. H3 acetylation (H3Ac, an activation mark) or H3 trimethylation on lysine 27 (H3K27me3, a repressive mark) were not affected.

Fig. 5.

Epigenetic alterations in the left hippocampus of adult animals. (A) H3K4me3. Number of hits significantly affected H3K4me3 (χ2 = 11.122, df = 3, P = 0.011). The three-hit group had significantly lower levels of H3K4me3 than all other groups (zero-hit P = 0.033; one-hit: P = 0.007; two-hit: P = 0.001) on Prom3. (B) H3K27me3. Number of hits did not affect H3K27me3. (C) Pan-acetylation on H3 (H3Ac). Number of hits did not affect H3Ac. Levels are relative to the zero-hit group. Mean and SEMs are shown. *P < 0.05.

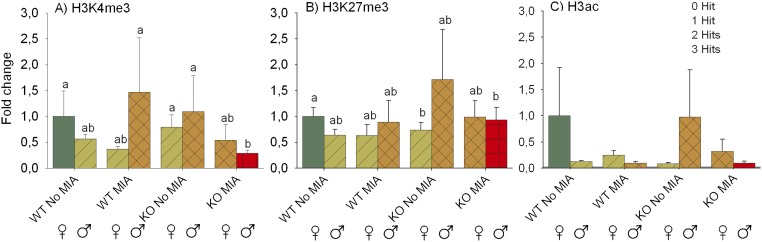

Looking at the individual hits, we found a significant three-way interaction between genotype, MIA, and sex on H3K4me3 levels in the left hippocampus. Further investigation revealed that this three-way interaction was caused by a two-way interaction between MIA and genotype in males only: only in KO males did MIA cause a decrease in H3K4me3 levels. There was no significant three-way interaction between the factors on H3Ac or H3K27me3 (Fig. S5).

Fig. S5.

Bar graph of epigenetic alterations in the left hippocampus of adult animals. Levels are relative to the WT no-stress females. (A) H3K4me3. There is a significant three-way interaction between genotype, MIA, and sex (χ2 = 6.330, df = 1, P = 0.012), caused by a two-way interaction between MIA and genotype that is only present in males (χ2 = 7.220, df = 1, P = 0.007): in WT males, MIA has no significant effect, whereas in KO males MIA causes a decrease in H3K4me3 levels (males χ2 = 9.241, df = 1, P = 0.002). Therefore, a genotype difference is observed in MIA males (χ2 = 6.633, df = 1, P = 0.010), and a sex difference is observed in MIA KO males (χ2 = 4.956, df = 1, P = 0.026). (B) H3K27me3. There is no significant three-way interaction between genotype, MIA, and sex. There is a significant genotype × sex effect (χ2 = 6.132, df = 1, P = 0.013). In females only there is a significant difference between WTs and KOs (χ2 = 7.306, df = 1, P = 0.007; KOs show lower levels of H3K27me3). In males only there is a MIA effect (χ2 = 26.560, df = 1, P < 0.001; prenatally stressed males show lower levels of H3K27me3 than control males). (C) H3 Acetylation (H3ac). There are no main effects of sex, MIA, or genotype on levels of H3Ac. No interaction effects are present either. Mean and SEMs are shown.

SI Methods

All experimental protocols were conducted according to US National Institutes of Health guidelines for animal research and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at The Rockefeller University (protocol #11456).

Subjects.

Cntnap2 heterozygous females on a C57BL/6J background were obtained from the Peles laboratory (Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel) via the Abrahams laboratory (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York). Cntnap2 KO and WT mice were obtained from heterozygous crossings. The discovery of a vaginal plug was marked as GD1. The date of birth was set as PD0. The mice were held in clear polypropylene cages containing corncob bedding and Enviro-Dri and Nestlets as enrichment.

At gestational day GD7, the pregnant females were randomly assigned to a MIA and a control group. We chose to induce MIA in the first trimester, because stressors during this period may have detrimental effects on brain and behavior in males specifically (61, 62). The MIA group received 0.30 mg/kg LPS in saline by subcutaneous injections—a dose found to not cause reabsorption of the litter (63)—whereas the control females received saline only. In animal models, MIA is often induced through LPS exposure. LPS evokes a strong and reliable fetal systemic, amniotic, and placental inflammatory response. It produces an elevated inflammatory cytokine production in the amniotic fluid and an elevated IL-17A response in liver CD4+ Th17 cells after stimulation (64). Th17 cells and the associated IL-17a were recently shown to be required for MIA-induced behavioral deficits (65).

At GD16, the pregnant females were separated and housed individually under a reversed 12-h:12-h light:dark cycle (lights on at 10:00 PM). The animal rooms were maintained at 21 ± 1 °C. Food and water were available ad libitum, except for 4 h immediately after the subcutaneous injection, during which food was taken away to standardize food intake (63). Bedding material was available and nesting material (Nestlets) was offered through the wire mesh lid (together with the food in the food compartment). Nesting material used (an indicator of maternal behavior) was measured for four LPS and four saline litters. There was no significant effect of LPS on the amount of nesting material used [average: 15.35 g (saline) vs. 18.95 g (LPS); one-way ANOVA: F = 0.957, P = 0.366]. At PD7, the pups were individually marked with one toe clip, of which the tissue was used for genotyping. At PD21 the pups were weaned and housed in same sex groups (maximum five per cage). To avoid litter effects, we never used more than two mice per experimental group from each litter. All experiments were performed between 1:00 PM and 6:00 PM. At PD50 ± 1 the mice were killed, brains removed, the left and right hippocampus dissected and stored either in RNAlater to facilitate gene expression assays or frozen and stored at −70 °C until processed to study epigenetic modifications.

General Statistical Methods.

Data organized to investigate the three-hit hypothesis (four categories: zero hits to three hits) are analyzed either with an ANOVA (on raw or on transformed data) or with a generalized linear model depending on the distribution of the data and the best fit to the model (Dataset S1). Generalized linear models are able to handle a wider variety of distributions, such as the negative binomial regression model, which is developed for modeling count data (used on the number of USVs). When the overall test showed at least a trend-level effect of the number of hits (P < 0.1), the data were analyzed further by means of least-significant difference post hoc tests.

Data organized to investigate the individual hits (genotype, MIA, and sex) were analyzed using the same models as used for the three-hit hypothesis. For all measures (Dataset S1) we performed at least three tests: (i) one analysis to investigate the main effects; (ii) one analysis to investigate the two-way interactions (all main effects were included in the model); and (iii) one analysis to investigate the three-way interaction (all lower-level interactions and the main effect were included in the model). When the analyses concerning the interaction effects showed at least a trend-level effect (P < 0.1) the data were analyzed further (post hoc) by splitting the data on one of the factors that were involved in the interaction effect and repeating the analysis for the other factor (e.g., if we found a sex × MIA effect, we would analyze the effect of MIA in males and females separately).

All analyses were performed in SPSS 17.0 (SPSS Inc.).

Ultrasonic Vocalizations.

At PD3, the pups were removed from the dam and placed under a heat lamp. Subsequently, the pups were removed from the rest of the litter and placed in an individual heated box in a soundproof environment to record USVs for 5 min using the Avisoft-UltraSoundGate 116 Hb with a high-quality condenser microphone CM16/CMPA. Sample size was 10 per group (80 pups in total). Data transformation on the number of USVs did not lead to normalization of the data. Therefore, the data were analyzed using a generalized linear model with a negative binomial distribution and a log-link function, which resulted in good model fits (Pearson χ2/df were between 1.066 and 1.092).

Open Field.

Locomotor activity in a novel environment was tested on PD40 ± 1. The animals were removed from their home cage and placed individually in the Plexiglas open-field arena (42 cm × 42 cm) for 10 min under red light. The experimenter exited the room and the mouse’s behavior was recorded. The videos were analyzed using Noldus’ EthoVision XT (Noldus Information Technology BV). The measures obtained were time spent in the middle of the apparatus (14 cm × 14 cm middle area) and total distance traveled. Sample sizes were as follows: WT no-MIA females: 9; WT no-MIA males: 9; WT MIA females: 7; WT MIA males: 9; KO no-MIA females: 8; KO no-MIA males: 10; KO MIA females: 8; KO MIA males: 8. Total distance traveled was normally distributed and time spent in the middle of the apparatus was normally distributed after a square root transformation.

Social Recognition.

At PD41 ± 1, the animals were individually housed with bedding and Enviro-Dri enrichment and left undisturbed for at least 3 d, at which time they were tested on social recognition under red light. Unfamiliar age- and sex-matched intact stimulus mice were placed in wire mesh containers (8.2-cm diameter, 10 cm high), for which clear Plexiglas lids were manufactured. Olfactory cues thus readily passed, whereas direct interactions between the focal and stimulus mice were prevented (66, 67). Before the test, the stimulus mice were gently habituated to being in the container and focal mice were habituated to having an empty container in their home cage, as well as having a Plexiglas top covering their cage instead of a wire top. Each focal mouse was tested five times (tests 1–5) in their home cage, in which a container with a stimulus mouse was introduced. A clean container was used for each test, so that the novelty of the container was maintained constant over tests. Each test lasted 5 min and the tests were repeated with a 15-min interval. During the 15-min interval the same empty container was placed back in the home cage of the focal mouse. In the first four tests the same stimulus mouse was used, whereas for the fifth test, the stimulus mouse was replaced with another unfamiliar sex- and age-matched conspecific. The placement of the containers over the five tests was kept constant. During the tests the mice were left undisturbed and their behavior was videotaped and subsequently scored using the software program JWatcher (www.JWatcher.UCLA.edu). Social investigation was defined as sniffing the wire mesh part of the container. Two focal mice were tested simultaneously with a visual barrier in between the tests to prevent interactions between the focal mice. After the test, vaginal smears of both focal females and the female stimulus mice were obtained to determine their estrous cycle (68). In both groups the distribution of estrous stage was not significantly different from chance levels. Because of mice escaping from the test box, six mice had to be excluded from analyses. Additionally, three mice were excluded because of technical difficulties with the camera. Sample sizes were as follows: WT no MIA females: 9; WT no MIA males: 10; WT MIA females: 7; WT MIA males: 8; KO no MIA females: 9; KO no MIA males: 7; KO MIA females: 7; KO MIA males: 7. The data were square root-transformed to satisfy assumptions of normality and analyzed using repeated-measures ANOVA [five levels (trials 1–5); between-subject factor: number of hits or MIA, genotype, and sex). Repeated-measures ANOVA were also used as post hoc analyses on the three-hit categories regarding habituation [four levels (trials 1–4); no between-subject factor, for each hit executed separately] or dishabituation [two levels (trials 4–5); no between-subject factor, for each hit executed separately]. Similarly, repeated-measures ANOVA were used as post hoc analyses on the effect of the individual hits regarding habituation [four levels (trials 1–4); between-subject factor: MIA, genotype, and sex] or dishabituation [two levels (trials 4–5); between-subject factor: MIA, genotype, and sex].

RNA Isolation and Gene Expression.

Total RNA was isolated from whole left hippocampus using TriZol reagent (Life Technologies) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Only RNA with an A260/280 value higher than 1.8 was used for further analyses. An equal amount (100 ng) of total RNA was reverse-transcribed using a High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Life Technologies) and the resultant cDNA was used as template for qPCR. TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Life Technologies) were used to amplify mRNA for the Crhr1 gene, ID: Mm00432670_m1. Eukaryotic 18S rRNA (4352930E) was used as internal control. The relative ratio of the expression of the gene was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method (60). Sample sizes of RNA samples originating from the left hippocampus was seven for each of the eight groups, except for KO MIA females, which consisted of eight mice. Sample sizes of RNA samples originating from the right hippocampus was eight for each of the eight groups, except for WT no MIA females, which consisted of five mice and KO MIA females, which consisted of six mice. Plates held equal numbers of each treatment group as much as possible. Data were log-transformed to meet the assumptions of normality. An ANOVA was used with plate number as random factor. Least-significant difference post hoc tests were used to test the planned comparisons.

To investigate whether Crh or Crhr1 was related to social recognition we used the log-transformed gene-expression data (data followed a normal distribution after transformation) and the total time the focal animal socially sniffed the conspecific mouse over the first four trials [sum of the total time socially sniffing in trials 1–4 (habituation phase); this followed a normal distribution]. Additionally, we repeated the test, now only using the time socially sniffing in the last trial (during the dishabituation phase).

ChIP and qPCR.

ChIP assays were performed using EZ-Magna ChIP kit (Millipore) in three batches following the manufacturer’s instructions. In short, mouse hippocampi were dissected (using protease inhibitor mixture), snap frozen, and stored at −70 °C until use. At time of use the hippocampi of two mice were combined, minced into ∼1-mm pieces, and cross-linked in 1% formaldehyde at room temperature for 15 min. After quenching and washing out the formaldehyde, tissue was homogenized and cells were lysed in cold lysis buffer. Nuclei were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in nuclear lysis buffer. Before sonication, the nuclei were incubated on ice for 1 h. Next, 300 μL was transferred to a glass sonication vial and sonicated in a Covaris S2 Focused Ultrasonicator 3 × 2 min with a 1-min break in between sonication bouts, optimized to produce ∼500-bp fragments. Samples were diluted in ChIP dilution buffer and incubated overnight at 4 °C with magnetic protein A beads and antitrimethyl histone 3 lysine 4 (H3K4me3 from Millipore; activation mark), antitrimethyl-histone 3 lysine 27 (H3K27me3 from Cell Signaling; repression mark), pan-acetylated H3 (H3Acetyl, from Millipore), or mouse IgG as negative control (from Millipore). Ten percent of each sample was saved as input. After several washes the pulled-down protein–DNA complexes were reverse cross-linked at 65 °C with rotation for 2 h and at 95 °C for 10 min, after which the samples were cooled down to room temperature and the genomic DNA was purified. qPCR was used to measure the amount of immunoprecipitated DNA on the promoter area of the mouse Crhr1 gene (accession no. NM_007762). The forward primer sequence used was (5′→3′) GGGAACCACCCAAATGTAGT and the reverse primer sequence used was (5′→3′) GCGGGATTTAGAAGGCTAGT. Primers were designed using PrimerQuest (Integrated DNA Technologies). Ct values were normalized to those from the input and statistically controlled for batch number. In each ChIP and qPCR assay, all experimental groups were evenly represented as much as possible. Sample sizes were as follows: for H3Acetylation: WT no MIA females: 5; WT no MIA males: 4; WT MIA females: 3; WT MIA males: 4; KO no MIA females: 5; KO no MIA males: 3; KO MIA females: 3; KO MIA males: 5. For H3K4me3: WT no MIA females: 5; WT no MIA males: 4; WT MIA females: 3; WT MIA males: 5; KO no MIA females: 5; KO no MIA males: 3; KO MIA females: 3; KO MIA males: 4. For H3K27me3: WT no MIA females: 5; WT no MIA males: 4; WT MIA females: 3; WT MIA males: 3; KO no MIA females: 5; KO no MIA males: 3; KO MIA females: 3; KO MIA males: 4. Data were analyzed using a generalized linear model with a γ distribution and a log-link function.

Discussion

ASD, one of the most severe of the childhood psychiatric disorders, is likely to often be a result of the interplay between genetic and environmental factors. However, because of the complexity of the potentially relevant studies, this interplay is often neglected in the literature. Here, we have demonstrated that a genetic and an environmental factor show a complex interplay with each other as well as with the sex of the organism in a subset of the autism behavioral domains.

Besides our study’s relevance in the ASD field, the current study may be of interest to the general field of neurodevelopmental disorders. First, CNTNAP2 functioning is associated to a wide variety of developmental disorders, such as childhood apraxia of speech and language impairments (38), epilepsy, and schizophrenia (39). Second, our finding that MIA can have male-specific effects (social recognition and histone modifications) may also be of interest to the general field of neurodevelopmental disorders because of the growing body of evidence showing a male-specific vulnerability to develop a wide variety of neurodevelopmental disorders, such as attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, dyslexia, specific language impairment, and Tourette syndrome (reviewed in ref. 40).

Our data corroborate earlier studies that have shown that the number of USVs is reduced because of the Cntnap2 mutation (17), following MIA (14, 41), and because of being male (42). Our study suggests that these factors do not synergistically interact with each other to affect the number of USVs at PD3; instead, we showed a cumulative effect, such that the more hits a subject was exposed to, the fewer USVs it emitted.

Similarly, studies have shown that, in agreement with the present results, social recognition is affected by the Cntnap2 mutation (43). We did not replicate the finding that social recognition in males is higher compared with females (44). Although studies have investigated the effect of MIA on social behavior in rodents (e.g., refs. 45 and 46), we are not aware of studies that have investigated the effect of MIA on social recognition. Our study exposed a sex-specific effect of MIA; social recognition was affected in males only. The Connors et al. (45) study in rats also found a male-specific effect of MIA, but they observed an overall decrease in social interactions, which we only see in the MIA-exposed male KO mice, not in the WT mice, possibly accounted for by a species-specific effect of MIA.

Our data suggest that the three hits have some synergistic effects on social recognition. Surprisingly, mice that were exposed to two hits performed somewhat better (trend level) than the zero-hit category. Mice exposed to three hits performed significantly worse than mice exposed to two-hits. In contrast to all other groups, the three-hit mice showed no habituation to the same animal in the four trials of the test and they showed no dishabituation to a new stimulus mouse in trial 5 of the test (with the exception of only a borderline dishabituation of the two-hit mice). This result suggests that the Cntnap2 mutation leaves males vulnerable to the effect of MIA. Whether the lack of apparent social recognition in the three-hit mice can be entirely attributed to a lack of true social recognition, or whether these mice just show a total lack of social interest, cannot be distinguished. However, it is clear that these mice do show clear deficits in social behavior in the social-recognition test.

The decreased social behavior and social recognition of the three-hit mice is not likely to be mediated by a decrease in overall locomotor activity or increased anxiety, as the open-field data showed increased locomotor activity in the two-hit and three-hit mice compared with the zero-hit mice and no differences in anxiety. The analyses on the individual hits showed that the Cntnap2 mutation was responsible for differences between the groups in locomotor activity, in agreement with previous work (17).

Furthermore, the effects of MIA are not likely to be mediated by differences in maternal behavior, as we found no effect of MIA on the amount of nesting material (a measure for maternal behavior) used.

MIA can result in increased levels of inflammatory cytokines in the fetal environment and can activate the fetal HPA axis (47). Upon activation of the HPA axis, the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus releases CRH, which leads to release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) by the anterior pituitary, which in turn leads again to release of cortisol by the cortex of the adrenal glands. Cortisol inhibits both CRH and ACTH release, which results in a negative feedback mechanism. Prenatal HPA axis activation has long-lasting effects on brain and behavior (48). Several studies suggest that the HPA axis may be altered in ASD (see ref. 49 and references therein). The HPA axis alterations can have wide effects on behaviors and has been attributed as being one of the main correlates of social deficits in patients with fragile X syndrome (50). Prenatal LPS exposure, which activates the fetal HPA axis (47), causes structural, neurophysiological, and functional changes in the hippocampus (e.g., refs. 51–53) and the hippocampus has been repeatedly shown to be affected in ASD (refs. 54–56; because many studies do not consider lateralization, some studies may find no or smaller effects if they only consider one side of the brain, or combine the results from the left and right hemisphere). We investigated the CRH system in the hippocampus by means of gene-expression assays and found trend-level differences between the three-hit categories, both for Crh and Crhr1. Surprisingly, post hoc tests showed that Crh mRNA levels were increased in the two-hit mice. Notably, the two-hit mice tended to perform better in the social-recognition task. Because we also found a trend for a positive correlation between Crh mRNA expression in the hippocampus and social behavior in the social-recognition data, it may be worthwhile to look further into this link in the future.

Post hoc tests further showed that Crhr1 mRNA expression was lower in the hippocampi of mice exposed to all three hits. The analyses on the separate hits showed a significant three-way interaction, whereas the individual hits did not show a significant effect, indicating a possible synergetic effect of the MIA, the Cntnap2 mutation, and being male on Crhr1 mRNA expression. These changes in mRNA expression may underlie the effects seen in the social-recognition test, as we found a significant positive correlation between Crhr1 mRNA expression and social behavior in the social-recognition task. These correlations corroborate studies that show that HPA-axis disturbances can cause deficits in social behavior later in life (reviewed in ref. 57) and that social behavior is (co)regulated by the hippocampus (58).

Subsequently, we showed that the down-regulated Crhr1 gene expression in the hippocampus of the three-hit category may possibly be mediated by a decrease in the protranscriptional H3K4 trimethylation of the promoter area of the Crhr1 gene. However, we do note that the down-regulation of Crh and Crhr1 gene expression was only changed at a trend level. The possible changes in Crh and Crhr1 are therefore not likely to be the only factors underlying the changes observed in social-recognition behavior. Furthermore, they do not seem to underlie the changes observed in USVs during the maternal separation paradigm and in hyperactivity.

Limitations.

Our data highlight one line of evidence showing that an environmental and genetic factor can interact to cause sex-specific effects; a line of evidence that leads from Crhr1 promoter function to Crhr1 mRNA levels, arguably leading to behavioral changes in this mouse model of ASD. However, the exact mechanism underlying the effect of the Cntnap2 mutation (in concert with MIA) on Crhr1 functioning remains elusive. The sample sizes in this study—especially concerning the histone modification (because of the fact that samples from individuals had to be pooled to have adequate material)—are low and thus limit interpretation until a new, larger study is completed.

The MIA and the Cntnap2 data held up despite potential subtleties. That is, to just give one of many examples, even within a species the effect of MIA can be widespread as different mouse strains react differently to MIA (59). Furthermore, the extent of the contribution of the interaction with the Cntnap2 gene may be limited, as heterozygous single-nuclueotide variants in the CNTNAP2 gene do not seem to be associated with ASD to a high level (60).

We realize that this line of research is just one of many possible pathways of how the environment can interact with the genetic background of an individual. Our data show a proof-of-principle that such a pathway can cause sex-specific effects, but it is more than likely that many of such synergistic interactions will be at work.

Methods

Subjects.

Cntnap2 heterozygous females on a C57BL/6J background were obtained from the Peles laboratory (Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel) via the Abrahams laboratory (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York). Cntnap2 KO and WT mice were obtained from heterozygous crossings. The discovery of a vaginal plug was marked as gestational day 1 (GD1). At GD7, the pregnant females were randomly assigned to a MIA and a control group. The MIA group received 0.30 mg/kg LPS in saline by subcutaneous injections, whereas the control females received saline only. The date of birth was set as PD0. At PD21 the pups were weaned and housed in same sex groups (maximum five per cage). To avoid litter effects, we never used more than two mice per experimental group from each litter. At PD50 ± 1, the mice were killed and hippocampi isolated for gene expression or ChIP assays.

All experimental protocols were conducted according to US National Institutes of Health guidelines for animal research and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at The Rockefeller University (protocol #11456).

Behavioral Tests.

At PD3, pups were removed from the dam and USVs were recorded for each individual separately for 5 min using the Avisoft-UltraSoundGate 116 Hb with high-quality condenser microphone CM16/CMPA. At PD40 ± 1, locomotor activity in a novel environment was tested using an open-field set-up. The measures obtained were time spent in the middle of the apparatus (14 cm × 14 cm middle area) and total distance traveled. At PD45 ± 2 social recognition was tested. Each focal mouse was tested five times (tests 1–5) in their home cage in which a container with an age- and sex-matched stimulus mouse was introduced. Each test lasted 5 min and the tests were repeated with a 15-min interval. In the first four tests the same stimulus mouse was used, whereas for the fifth test the stimulus mouse was replaced with another unfamiliar sex- and age-matched conspecific. During the tests the mice were left undisturbed and their behavior was videotaped and subsequently scored using the software program JWatcher (www.JWatcher.UCLA.edu).

Gene-Expression Assays.

Total RNA was isolated from whole left hippocampus using TriZol reagent (Life Technologies) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Equal amount (100 ng) of total RNA was reverse-transcribed using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Life Technologies) and the resultant cDNA was used as template for quantitative PCR (qPCR). TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Life Technologies) were used to amplify mRNA for the Crhr1 gene, ID: Mm00432670_m1. Eukaryotic 18S rRNA (4352930E) was used as internal control. The relative ratio of the expression of the gene was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method (59).

ChIP and qPCR.

ChIP assays were performed using EZ-Magna ChIP kit (Millipore) in three batches following the manufacturer’s instructions. To have enough material, the hippocampi of two mice were combined. qPCR was used to measure the amount of immunoprecipitated DNA on the promoter area of the mouse Crhr1 gene (accession no. NM_007762). Primers were designed using PrimerQuest (Integrated DNA Technologies).

General Statistical Methods.

Data organized to investigate the three-hit hypothesis (four categories: zero hits to three hits) are analyzed either with an ANOVA (on raw or on transformed data) or with a generalized linear model depending on the distribution of the data and the best fit to the model (Dataset S1). Data organized to investigate the individual hits (genotype, MIA, and sex) were analyzed using the same models as used for the three-hit hypothesis. For all measures (Dataset S1) we performed at least three tests: (i) one analysis to investigate the main effects, (ii) one analysis to investigate the two-way interactions (all main effects were included in the model), and (iii) one analysis to investigate the three-way interaction (all lower level interactions and the main effect were included in the model). All analyses were performed in SPSS 17.0 (SPSS Inc.).

Additional details are available in SI Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by an Autism Science Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship 13-1002 (to S.M.S.) and Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative Explorer Award 230933 (to D.W.P.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1619312114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Fombonne E. Epidemiological surveys of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders: An update. J Autism Dev Disord. 2003;33(4):365–382. doi: 10.1023/a:1025054610557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schaafsma SM, Pfaff D. Frontiers in neuroendocrinology etiologies underlying sex differences in autism spectrum disorders. 2014;35(3):255–251. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hallmayer J, et al. Genetic heritability and shared environmental factors among twin pairs with autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(11):1095–1102. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DiCicco-Bloom E, et al. The developmental neurobiology of autism spectrum disorder. J Neurosci. 2006;26(26):6897–6906. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1712-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breedlove SM. Minireview: Organizational hypothesis: Instances of the fingerpost. Endocrinology. 2010;151(9):4116–4122. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris JA, Jordan CL, Breedlove SM. Sexual differentiation of the vertebrate nervous system. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(10):1034–1039. doi: 10.1038/nn1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baron-Cohen S, et al. Elevated fetal steroidogenic activity in autism. Mol Psychiatr. 2014;20(3):1–8. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strauss KA, et al. Recessive symptomatic focal epilepsy and mutant contactin-associated protein-like 2. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(13):1370–1377. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doane AS, et al. An estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer subset characterized by a hormonally regulated transcriptional program and response to androgen. Oncogene. 2006;25(28):3994–4008. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heemers HV, et al. Identification of a clinically relevant androgen-dependent gene signature in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71(5):1978–1988. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patterson PH. Immune involvement in schizophrenia and autism: Etiology, pathology and animal models. Behav Brain Res. 2009;204(2):313–321. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gardener H, Spiegelman D, Buka SL. Perinatal and neonatal risk factors for autism: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2011;128(2):344–355. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arndt TL, Stodgell CJ, Rodier PM. The teratology of autism. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2005;23(2–3):189–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malkova NV, Yu CZ, Hsiao EY, Moore MJ, Patterson PH. Maternal immune activation yields offspring displaying mouse versions of the three core symptoms of autism. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26(4):607–616. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirsten TB, et al. Hypoactivity of the central dopaminergic system and autistic-like behavior induced by a single early prenatal exposure to lipopolysaccharide. J Neurosci Res. 2012;90(10):1903–1912. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pfaff DW, Rapin I, Goldman S. Male predominance in autism: Neuroendocrine influences on arousal and social anxiety. Autism Res. 2011;4(3):163–176. doi: 10.1002/aur.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peñagarikano O, et al. Absence of CNTNAP2 leads to epilepsy, neuronal migration abnormalities, and core autism-related deficits. Cell. 2011;147(1):235–246. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stevens T, Peng L, Barnard-Brak L. The comorbidity of ADHD in children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2016;31:11–18. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kerns CM, et al. Not to be overshadowed or overlooked: Functional impairments associated with comorbid anxiety disorders in youth with ASD. Behav Ther. 2015;46(1):29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sztainberg Y, Kuperman Y, Tsoory M, Lebow M, Chen A. The anxiolytic effect of environmental enrichment is mediated via amygdalar CRF receptor type 1. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15(9):905–917. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elliott E, Ezra-Nevo G, Regev L, Neufeld-Cohen A, Chen A. Resilience to social stress coincides with functional DNA methylation of the Crf gene in adult mice. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13(11):1351–1353. doi: 10.1038/nn.2642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charil A, Laplante DP, Vaillancourt C, King S. Prenatal stress and brain development. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2010;65(1):56–79. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan W, et al. Bisphenol A differentially activates protein kinase C isoforms in murine placental tissue. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2013;269(2):163–168. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2013.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang H, et al. Genistein upregulates placental corticotropin-releasing hormone expression in lipopolysaccharide-sensitized mice. Placenta. 2011;32(10):757–762. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2011.07.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Z, van Praag H. Maternal immune activation differentially impacts mature and adult-born hippocampal neurons in male mice. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;45:60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mattei D, et al. Minocycline rescues decrease in neurogenesis, increase in microglia cytokines and deficits in sensorimotor gating in an animal model of schizophrenia. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;38:175–184. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cui K, Ashdown H, Luheshi GN, Boksa P. Effects of prenatal immune activation on hippocampal neurogenesis in the rat. Schizophr Res. 2009;113(2-3):288–297. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Veenit V, Riccio O, Sandi C. CRHR1 links peripuberty stress with deficits in social and stress-coping behaviors. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;53:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fan J-M, et al. Upregulation of PVN CRHR1 by gestational intermittent hypoxia selectively triggers a male-specific anxiogenic effect in rat offspring. Horm Behav. 2013;63(1):25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fenoglio KA, Brunson KL, Baram TZ. Hippocampal neuroplasticity induced by early-life stress: Functional and molecular aspects. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2006;27(2):180–192. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cottrell EC, Seckl JR. Prenatal stress, glucocorticoids and the programming of adult disease. Front Behav Neurosci. 2009;3(15):19. doi: 10.3389/neuro.08.019.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shamay-Tsoory SG, Gev E, Aharon-Peretz J, Adler N. Brain asymmetry in emotional processing in Asperger syndrome. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2010;23(2):74–84. doi: 10.1097/WNN.0b013e3181d748ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conturo TE, et al. Neuronal fiber pathway abnormalities in autism: An initial MRI diffusion tensor tracking study of hippocampo-fusiform and amygdalo-fusiform pathways. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2008;14(6):933–946. doi: 10.1017/S1355617708081381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Conti E, et al. Lateralization of brain networks and clinical severity in toddlers with autism spectrum disorder: A HARDI diffusion MRI study. Autism Res. 2016;9(3):382–392. doi: 10.1002/aur.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoshimura Y, et al. Atypical brain lateralisation in the auditory cortex and language performance in 3- to 7-year-old children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder: A child-customised magnetoencephalography (MEG) study. Mol Autism. 2013;4(1):38. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-4-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moskal JR, Kroes RA, Otto NJ, Rahimi O, Claiborne BJ. Distinct patterns of gene expression in the left and right hippocampal formation of developing rats. Hippocampus. 2006;634:629–634. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hunter RG, McCarthy KJ, Milne TA, Pfaff DW, McEwen BS. Regulation of hippocampal H3 histone methylation by acute and chronic stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(49):20912–20917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911143106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Centanni TM, et al. The role of candidate-gene CNTNAP2 in childhood apraxia of speech and specific language impairment. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2015;168(7):536–543. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Friedman JI, et al. CNTNAP2 gene dosage variation is associated with schizophrenia and epilepsy. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13(3):261–266. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baron-Cohen S, et al. Why are autism spectrum conditions more prevalent in males? PLoS Biol. 2011;9(6):e1001081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coiro P, et al. Impaired synaptic development in a maternal immune activation mouse model of neurodevelopmental disorders. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;50:249–258. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wright SL, Brown RE. Sex differences in ultrasonic vocalizations and coordinated movement in the California mouse (Peromyscus californicus) Behav Processes. 2004;65(2):155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brunner D, et al. Comprehensive analysis of the 16p11.2 deletion and null cntnap2 mouse models of autism spectrum disorder. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0134572. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karlsson SA, Haziri K, Hansson E, Kettunen P, Westberg L. Effects of sex and gonadectomy on social investigation and social recognition in mice. BMC Neurosci. 2015;16(1):83. doi: 10.1186/s12868-015-0221-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Connors EJ, Shaik AN, Migliore MM, Kentner AC. Environmental enrichment mitigates the sex-specific effects of gestational inflammation on social engagement and the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis-feedback system. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;42:178–190. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ibi D, et al. Combined effect of neonatal immune activation and mutant DISC1 on phenotypic changes in adulthood. Behav Brain Res. 2010;206(1):32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gayle DA, et al. Maternal LPS induces cytokines in the amniotic fluid and corticotropin releasing hormone in the fetal rat brain. Am J Physiol Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;286(6):R1024–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00664.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Darnaudéry M, Maccari S. Epigenetic programming of the stress response in male and female rats by prenatal restraint stress. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2008;57(2):571–585. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Corbett BA, Mendoza S, Wegelin JA, Carmean V, Levine S. Variable cortisol circadian rhythms in children with autism and anticipatory stress. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2008;33(3):227–234. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hessl D, Rivera SM, Reiss AL. The neuroanatomy and neuroendocrinology of fragile X syndrome. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2004;10(1):17–24. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baharnoori M, Brake WG, Srivastava LK. Prenatal immune challenge induces developmental changes in the morphology of pyramidal neurons of the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus in rats. Schizophr Res. 2009;107(1):99–109. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lowe GC, Luheshi GN, Williams S. Maternal infection and fever during late gestation are associated with altered synaptic transmission in the hippocampus of juvenile offspring rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295(5):R1563–R1571. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90350.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Golan HM, Lev V, Hallak M, Sorokin Y, Huleihel M. Specific neurodevelopmental damage in mice offspring following maternal inflammation during pregnancy. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48(6):903–917. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Endo T, et al. Altered chemical metabolites in the amygdala-hippocampus region contribute to autistic symptoms of autism spectrum disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(9):1030–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schumann CM, et al. The amygdala is enlarged in children but not adolescents with autism; the hippocampus is enlarged at all ages. J Neurosci. 2004;24(28):6392–6401. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1297-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.DeLong GR. Autism, amnesia, hippocampus, and learning. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1992;16(1):63–70. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(05)80052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sandi C, Haller J. Stress and the social brain: Behavioural effects and neurobiological mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16(5):290–304. doi: 10.1038/nrn3918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kogan JH, Frankland PW, Silva AJ. Long-term memory underlying hippocampus-dependent social recognition in mice. Hippocampus. 2000;10(1):47–56. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(2000)10:1<47::AID-HIPO5>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(6):1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Murdoch JD, et al. No evidence for association of autism with rare heterozygous point mutations in contactin-associated protein-like 2 (CNTNAP2), or in other contactin-associated proteins or contactins. PLoS Genet. 2015;11(1):e1004852. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mueller BR, Bale TL. Early prenatal stress impact on coping strategies and learning performance is sex dependent. Physiol Behav. 2007;91(1):55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mueller BR, Bale TL. Sex-specific programming of offspring emotionality after stress early in pregnancy. J Neurosci. 2008;28(36):9055–9065. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1424-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Coyle P, Tran N, Fung JNT, Summers BL, Rofe AM. Maternal dietary zinc supplementation prevents aberrant behaviour in an object recognition task in mice offspring exposed to LPS in early pregnancy. Behav Brain Res. 2009;197(1):210–218. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Luan R, et al. Maternal lipopolysaccharide exposure promotes immunological functional changes in adult offspring CD4+ T cells. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2015;73(6):522–535. doi: 10.1111/aji.12364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Choi GB, et al. The maternal interleukin-17a pathway in mice promotes autismlike phenotypes in offspring. 2016;351(6276):933–940. doi: 10.1126/science.aad0314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Choleris E, et al. An estrogen-dependent four-gene micronet regulating social recognition: A study with oxytocin and estrogen receptor-alpha and -beta knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(10):6192–6197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0631699100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Choleris E, et al. Involvement of estrogen receptor alpha, beta and oxytocin in social discrimination: A detailed behavioral analysis with knockout female mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2006;5(7):528–539. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Byers SL, Wiles MV, Dunn SL, Taft RA. Mouse estrous cycle identification tool and images. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35538. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.