Significance

Widespread use of solid fuels for cooking results in a significant source of anthropogenic emissions. Of foremost concern for indoor air quality, reductions to these emissions could also impact both climate and ambient air quality. These potential cobenefits are appealing to efforts aimed at reducing cookstove emissions on national to urban scales, but have yet to be comprehensively evaluated at these scales. We thus estimate the per cookstove impacts on ambient air quality and global mean surface temperature for every individual country with significant cookstove use, considering reductions to both aerosols and long-lived greenhouse gases over the next century. This estimation provides information for policy makers evaluating climate and ambient air quality cobenefits of cookstove intervention programs worldwide.

Keywords: aerosols, climate, human health, cookstoves, atmospheric modeling

Abstract

Residential solid fuel use contributes to degraded indoor and ambient air quality and may affect global surface temperature. However, the potential for national-scale cookstove intervention programs to mitigate the latter issues is not yet well known, owing to the spatial heterogeneity of aerosol emissions and impacts, along with coemitted species. Here we use a combination of atmospheric modeling, remote sensing, and adjoint sensitivity analysis to individually evaluate consequences of a 20-y linear phase-out of cookstove emissions in each country with greater than 5% of the population using solid fuel for cooking. Emissions reductions in China, India, and Ethiopia contribute to the largest global surface temperature change in 2050 [combined impact of −37 mK (11 mK to −85 mK)], whereas interventions in countries less commonly targeted for cookstove mitigation such as Azerbaijan, Ukraine, and Kazakhstan have the largest per cookstove climate benefits. Abatement in China, India, and Bangladesh contributes to the largest reduction of premature deaths from ambient air pollution, preventing 198,000 (102,000–204,000) of the 260,000 (137,000–268,000) global annual avoided deaths in 2050, whereas again emissions in Ukraine and Azerbaijan have the largest per cookstove impacts, along with Romania. Global cookstove emissions abatement results in an average surface temperature cooling of −77 mK (20 mK to −278 mK) in 2050, which increases to −118 mK (−11 mK to −335 mK) by 2100 due to delayed CO2 response. Health impacts owing to changes in ambient particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of 2.5 μm or less (PM2.5) amount to ∼22.5 million premature deaths prevented between 2000 and 2100.

Globally over 3 billion people presently use solid fuel for meal preparation (1). The extent of this activity and the associated air quality pollutant emissions have led to numerous cookstove intervention studies and programs, such as the Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves work to implement 60 million clean cookstoves by 2017 (cleancookstoves.org/about/news/11-20-2014-market-enabling-roadmap-phase-2-2015-2017.html). A primary goal of these efforts is to improve indoor air quality, estimated to cause ∼4.3 million premature deaths annually, along with enhancing livelihood of woman and children via reprieval from fuel collection and other solid fuel cooking-related tasks (2).

The magnitude of the emissions of aerosols, aerosol precursors, and greenhouse gases from solid fuel use has also motivated studies of the impact of these emissions on climate and ambient air quality. An estimated 370,000–500,000 global premature deaths in adults occur annually owing to ambient exposure to fine particulate matter associated with residential cookstoves (3–5), and there are as many as 1.0 million global annual premature deaths of adults and children under the age of 5 y from combined residential and commercial energy generation (which includes solid fuel use for cooking) (6). This is a significant fraction of the 2.9 million premature deaths owing to degraded ambient air quality from all sources (5). These emissions’ climate impacts have also been quantified to some extent; for example, Bailis et al. (7) estimate that 1.9–2.3 of the global CO2 emissions are from wood fuel, enough to cause a radiative forcing (RF) of 25–47 mW m−2 (8), whereas the aerosol RF ranges from −20 mW·m−2 to 80 mW·m−2 (9, 10). The large range of uncertainty in the aerosol climate impact of cookstoves stems from uncertainties regarding fuel characterization given coemissions of absorbing or reflective species, compounded by uncertainties in the interactions of aerosols with clouds (11, 12).

Although these previous studies have highlighted the potential cobenefits of reducing cookstove emissions globally, such findings are limited in terms of their relevance for evaluating domestic-scale mitigation efforts. First, the impacts of aerosols on climate and ambient air quality are highly spatially variable owing to several factors, and thus global-scale assessments may not well represent the consequences of national-scale action plans. Unlike long-lived greenhouse gases, which are well mixed in the atmosphere and have a constant impact per ton of emission globally, aerosols have atmospheric residences times on the order of 1 wk; their spatial distributions thus contain sharp gradients that lead to order of magnitude regional variances in their health and climate impacts per ton of emission, depending on factors such as their proximity to populated areas (e.g., ref. 13), their impact on RF in different regions (14), and the regional climate sensitivity to forcing (15). Second, integrated assessment of cookstove interventions must account for both greenhouse gas (GHG) and aerosols, which is a challenge owing to the disparate timescale of the climate impacts of aerosols (decades) compared with that of long-lived GHGs (centuries). Finally, modeling studies of aerosol health impacts are often detailed yet limited to a single region or are global yet suffer from errors in exposure estimation at coarse model scales (16).

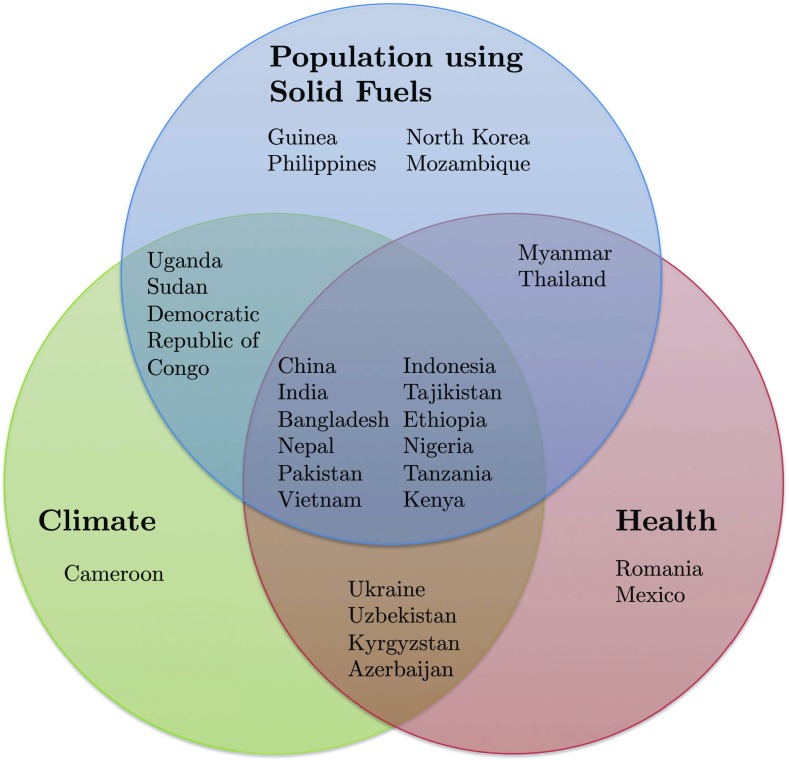

To address these limitations, here we estimate the transient (present day to 2100) climate and ambient health impacts of national-scale coemissions of aerosols, aerosol precursors, and GHGs resulting from a 20-y phase-out of cookstove emissions in each country with greater than 5 of the population using solid fuels for cooking (101 countries in total). Attribution of these impacts to emissions from individual countries and species is made possible through the use of adjoint sensitivity analysis, building on our earlier work evaluating climate impacts of carbonaceous aerosols (11) and of source attribution of exposure to ambient particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of 2.5 μm or less (PM2.5) resolved throughout the globe using remote sensing observations (13).

Methods

Transient climate and health impacts are calculated for a scenario in which emissions of aerosols, aerosol precursors, and GHGs from solid fuel cooking are linearly eliminated over a 20-y horizon. Details of the emissions, models, and methods summarized here are provided in Supporting Information.

Transient climate impacts are estimated as follows. Adjoint model calculations (14) are used to calculate the sensitivities of regional RF in four different latitude bands with respect to grid-scale emissions of aerosols and aerosol precursors. Regional RF values are combined with absolute regional temperature potentials (15, 17) to estimate surface temperature response. This approach, introduced in Lacey and Henze (11), is expanded here by including GHGs and transient temperature responses. GHG emissions are modeled using transient functions for species-specific radiative impacts (18, 19), which relate the timescale of emissions to the resulting transient RF impacts (Tables S1 and S2). These GHG RF impacts are then combined with the aerosol RF to estimate the total RF as a transient function. This net RF is multiplied by the transient global mean sensitivities and integrated for all prior years to estimate the temperature response of an emissions perturbation as a function of time. To account for uncertainties in RF, ranges of radiative efficiencies of short-lived climate pollutants (SLCPs) from multimodel ensemble estimates (8, 20, 21) are applied (Table S3). Whereas the climate responses to these ranges of RF estimates are calculated using absolute regional temperature potentials (ARTPs) derived from a single climate model [Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS)], other studies have found consistency between ARTP-based projections and mean surface temperature responses across models (SI Methods, Temperature Response). Further uncertainties in climate impacts are derived from ranges of emissions factors based on fuel characterizations (22, 23). The uncertainties in climate impacts from GHGs are estimated as 10 of their total impact and are combined with the species-specific SLCP errors in quadrature.

Table S1.

CO2 IRF coefficients from Joos et al. (18)

| Parameter | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 0.2173 | 0.2240 | 0.2824 | 0.2763 | |

| N/A | 394.4 | 36.54 | 4.304 |

N/A, not applicable.

Table S2.

Species-specific lifetimes from Myhre et al. (8)

| Species | |

| CH4 | 8.4 |

| N2O | 114 |

Table S3.

Scaling factors for direct RF () and various secondary radiative effects () for BC, OC, and secondary inorganic aerosol (SIA)

| Type | Species | Lower | Central | Upper |

| BC | 1.840 | 2.761 | 3.681 | |

| OC | 0.695 | 1.595 | 2.394 | |

| SIA | 0.256 | 0.567 | 1.001 | |

| BC | −0.143 | 1.000 | 1.471 | |

| OC | 1.019 | 1.560 | 1.740 | |

| SIA | 1.446 | 2.214 | 2.470 |

We also estimate global premature mortality due to chronic exposure to ambient concentrations of PM2.5. To mitigate uncertainties in exposure estimates owing to model resolution (e.g., ref. 16), satellite-derived PM2.5 concentrations (24) are used to redistribute GEOS-Chem PM2.5 concentrations from the to the scale following Lee et al. (13). Population-weighted PM2.5 exposure is calculated using population estimates at the same resolution (25), which have been rescaled to 2050 national-scale population based on 2010 United Nations World Population Prospects (https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/).

The modeled exposure estimates are combined with disease-specific relative risk (RR) parameters for disease-specific integrated exposure responses (IER) (26) for all people over the age of 30 y and country-level baseline mortality rates (27) to estimate premature deaths from exposure to ambient PM2.5. The causes of premature mortality considered are ischemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, cerebro-vascular disease, and lung cancer. The adjoint model is used to calculate the sensitivities of global premature deaths with respect to grid-scale speciated emissions perturbations (13). Transient health impacts are estimated by linear interpolation of sensitivities calculated for the present day and the year 2050 [using Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) 4.5 emissions] and are assumed to increase post-2050 following the same rate of change as 2020–2050 to approximate sustained changes in population. Uncertainties in the health response are calculated following Lee et al. (13), in which the model was run with perturbed IER responses and baseline mortality rates corresponding to 1 SD for each impact. These are combined with a comparison of results obtained using different satellite-derived PM2.5 surfaces (24, 28) to estimate the range of annual premature deaths attributed to ambient PM2.5 exposure from solid fuel cookstove use; our central estimate uses the Global Burden of Disease 2013 exposure dataset (24) for consistency with other health impacts studies.

SI Methods

This study evaluates the transient climate and ambient health impacts of a reduction in emissions of aerosols, aerosol precursors, and GHGs from solid fuel cooking. Present-day solid fuel cooking emissions are estimated by combining inventories for carbonaceous aerosols (42) and SO2 (43) with the national-scale population percentage using solid fuels (1). Emissions of CO2 and CH4 are estimated using emissions factors for carbonaceous aerosols (23, 34), accounting for the spatially variable fraction of nonrenewable solid biomass fuel (7). Results are calculated for a linear reduction in cookstove solid fuel use from year 2000 emissions to complete removal of emissions in 2020. These impacts are calculated using multiple GEOS-Chem adjoint model simulations corresponding to different timescales and impacts as described below.

GEOS-Chem.

The model used for this work is GEOS-Chem (44), a global chemical transport model, run at the 2° 2.5° resolution. Simulations use assimilated meteorology from the Goddard Earth Observing System (GEOS-5). Base anthropogenic emissions are the historical year 2000 RCP emissions from Lamarque et al. (43) and include aerosols such as BC and OC, along with aerosol precursors such as SO2, NOx, and NH3. Natural emissions from volcanoes, oceanic dimethyl sulfide, lightning, soil, and biogenic sources are the same as described in Lacey and Henze (11). We also refer the reader to Lacey and Henze (11) for description of aerosol processes, heterogenous chemistry, and depositional losses. The species modeled in this work include primary OC, primary BC, sulfate, and nitrate. When considering PM2.5, aerosol is calculated at a 35 relative humidity fraction and spatially variable ratio of organic matter to OC (45). Although SOA is not explicitly treated in the model, we consider the climate and health impacts from SOA to be 18 of the overall OC impacts, which is based on emissions factors of nonmethane volatile organic compounds (NMVOCs) from solid fuel use (34, 46) and the speciation and potential formation rates of NMVOCs from residential emissions (35).

The adjoint of the GEOS-Chem model (47) is also used for calculating cost function-specific sensitivities, in this case both regional RF (11, 14) and premature mortality due to exposure of ambient PM2.5 (13). Adjoint models allow for the efficient calculation of sensitivities with respect to gird-scale emissions that would take the equivalent of forward model runs. The GEOS-Chem adjoint model has been verified compared with traditional finite-difference techniques (47) and has been used as a tool in a number of previously published works.

Climate Impacts.

Temperature response.

In this work, the climate response for a change in emissions is calculated by combining adjoint model estimates of regional aerosol radiative forcing, following Lacey and Henze (11), with GHG RF parameterizations. Whereas the base version of the forward GEOS-Chem model calculates aerosol mass concentration, the model used here combines these estimates of grid-cell aerosol mass with an offline Mie theory calculation and the LIDORT radiative transfer model (48) to estimate the change in upward radiative flux from a base preindustrial atmosphere (14). The adjoint model then considers an infinitesimal perturbation in the cost function, in this case radiative forcing, and tracks that perturbation backward in time through the model processes to calculate the grid-scale model sensitivities,

| [S1] |

where RF is the regional radiative forcing for some base atmospheric condition, , and is the species ()-, year ()-, and grid cell ()-specific emissions. These sensitivities take into account all of the model processes and are used to calculate the RF for an emissions perturbation as

| [S2] |

where is an annual emissions perturbation of species , is the direct RF scaling factor, and is the semi- and indirect RF scaling factor (11), both of which are derived in Lacey and Henze (11) from multimodel estimates of global radiative forcing (8, 20, 49). These scaling factors, shown in Table S3, are used to bound estimates of radiative forcing and generally span the range of uncertainties in aerosol radiative impacts that have been pointed out in recent studies (e.g., refs. 39 and 50). For this work, the base atmosphere is 1850 and the perturbed cases are both the present-day case modeled around the year 2000 historical emissions (43) and a future case for the year 2050 anthropogenic emissions following the RCP 4.5 (51, 52). This paper also takes into account the latitudinal effects of radiative forcing following Lacey and Henze (11), therefore calculating a weighted RF based on four different latitude bands through the use of ARTPs (17, 49).

ARTPs were developed in Shindell and Faluvegi (15), using the Goddard Institute for Space Studies Earth system model, GISS-E, and represent a parameterization of the regional and global climate response based on changes in latitudinal RF. Shindell (17), Sand et al. (53), and Stohl et al. (54) have compared the regional and global mean surface temperature response from changes in short-lived climate pollutants calculated using ARTPs to those from fully coupled earth system models (ESMs) and find that there is agreement between the ARTP parameterization and the ESM calculated temperature response. Shindell (17) has compared the historical response calculated using ARTPs to three of the Atmospheric Chemistry and Climate Model Intercomparison Project (ACCMIP) models and found an approximate 20 error between all of the modeled outputs. When evaluating the Arctic temperature response to Northern Hemisphere emissions of BC, Sand et al. (53) found a 15% difference between the ARTP method and the NorESM model. The work of Stohl et al. (54) reports nearly identical multimodel mean responses following future emissions scenarios for four ESMs compared with ARTP-based estimates of global surface temperature responses, although the regional temperature responses varied by 20% in the polar regions and 5–10% in the northern midlatitudes and tropics.

To include the impacts of GHGs, RF is calculated by first estimating the concentration response, using impulse response functions (), which calculate the response to an emissions pulse. The form of the IRF for CO2 is

| [S3] |

where is the base year, is the year of interest, and and are constants derived from model calculations in Joos et al. (18) and shown in Table S1. Similarly, for non-CO2 GHG species, specific IRFs from Aamaas et al. (19) are

| [S4] |

where is the species’ atmospheric lifetime (8) shown in Table S2. These IRFs are then used to estimate the concentration response to a perturbation in annual emissions (), yielding

| [S5] |

where is response year, is the year of the emissions perturbation, and is a base year concentration of each species. is the unit conversion from global annual emissions (in gigatons) to parts per million for CO2 and parts per billion for CH4 and N2O.

The radiative impacts of this change in concentration are calculated following Aamaas et al. (19) to give the change in RF between two scenarios for a given year. For CO2, this is purely a function of CO2 concentrations (Eq. S6) whereas the CH4 impacts are a function of both base and present-year CH4 and N2O concentrations, although the estimated RF does not account for methane feedbacks on ozone formation, which have been shown to increase the RF by ∼20 (55, 56). The full equations are shown in Eqs S7 and S8 for each species, respectively:

| [S6] |

| [S7] |

| [S8] |

Given the transient RFs calculated in year from the equations above, the transient climate responses in subsequent years () are calculated as

| [S9] |

is the transient global mean climate sensitivity for temperature change in year calculated as (57)

| [S10] |

where is the equilibrium global mean sensitivity, here estimated as 1.06 K (W·m−2)−1. The first exponential correspondsto the response of the surface and shallow seas and the second exponential represents the thermal inertia of the deep ocean.

Health Impacts.

This work also considers the health impacts due to changes in the ambient concentrations of PM2.5 caused by anthropogenic emissions from solid fuel cooking. As explained in Lee et al. (13), the GEOS-Chem adjoint model uses estimated aerosol mass concentrations, satellite-derived PM2.5 concentrations, and integrated exposure response functions to calculate sensitivities of premature deaths due to ambient PM2.5 exposure with respect to grid-cell emissions. The model has been updated to include spatially variable organic matter to OC ratios from Philip et al. (45) instead of the constant value of 1.8 used in Lee et al. (13). To reduce errors associated with model resolution and exposure scale mismatch (16, 58) the model estimates population-weighted PM2.5, using satellite-derived global estimates of surface PM2.5 concentrations for 2010 at the resolution (24). These satellite datasets are used in two ways. First, they are used to redistribute aerosol mass concentrations within a modeled grid cell (model grid, ) to scales more appropriate for population-based metrics (subgrid, ) as shown in Eq. S11,

| [S11] |

where is the model-estimated PM2.5 concentrations, is the number of nonzero subgrid cells within the modeled grid cell , is the satellite-derived PM2.5 in subgrid cell , and is the model grid average satellite-derived PM2.5 concentrations. Second, for present-day calculations, the satellite data are also used to correct for model bias by rescaling the modeled grid cell aerosol mass concentrations to the satellite-derived values at the scale, as shown in Eq. S12,

| [S12] |

The satellite-corrected PM2.5 concentrations are then used in the model IER functions of Burnett et al. (26) to calculate the premature deaths () from exposure to ambient population-weighted PM2.5 as

| [S13] |

where is the mortality rate for different diseases (), specifically, ischemic heart disease (IHD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD), cerebro-vascular disease (CEV), and lung cancer. is the disease-specific relative risk parameters for a change in PM2.5 exposure and is grid-cell () population in the model year (). The factors for are derived in Lozano et al. (27) and are functions of a region’s mortality rate that make them difficult to predict for future cases because the uncertainties in health resource allocation and demographics are large. has been estimated for future cases by scaling the present-day population (25) to 2050 national-scale population based on 2010 United Nations World Population Prospects (https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/). Finally, is derived from Burnett et al. (26) and represents the health impact from a change in exposure to population-weighted PM2.5 due to different diseases.

The adjoint model is then used to estimate sensitivities for with respect to all model inputs as

| [S14] |

where is the model resolution-speciated emissions (13). These sensitivities are calculated around the atmospheric conditions, emissions, and population used in the model year (). This change in global premature deaths for a given change in grid-cell emissions is then calculated as

| [S15] |

where is a gridded change in emissions of a species for a given change in anthropogenic activity under that model year. This first-order approximation of the response of to emissions perturbations for individual species in individual grid cells has been validated in Lee et al. (13), using finite difference calculations of the actual response to 10% perturbations, which have a regression slope of 0.8, 0.95, 0.93, and 1.01 for NOx, SO2, NH3, and BC,respectively.

To account for the difference between satellite reanalysis methods in the bounds of our health impacts we have compared the model results using Brauer et al. (24) as the central estimate and using the dataset from van Donkelaar et al. (28) as a bound for the health impacts. The upper and lower bounds are calculated by running the full model with each dataset independently and then using the maximum and minimum exposure estimates for each grid cell, along with the corresponding adjoint sensitivities to calculate the bounds of premature deaths from a given change in emissions. In general, the model using the satellite-derived product from van Donkelaar et al. (28) tends to estimate lower population-weighted PM2.5 due to the differences in the subgrid spatial distributions of surface PM2.5, but in regions that this is not the case, these results are used as the upper bound instead.

Results

Climate.

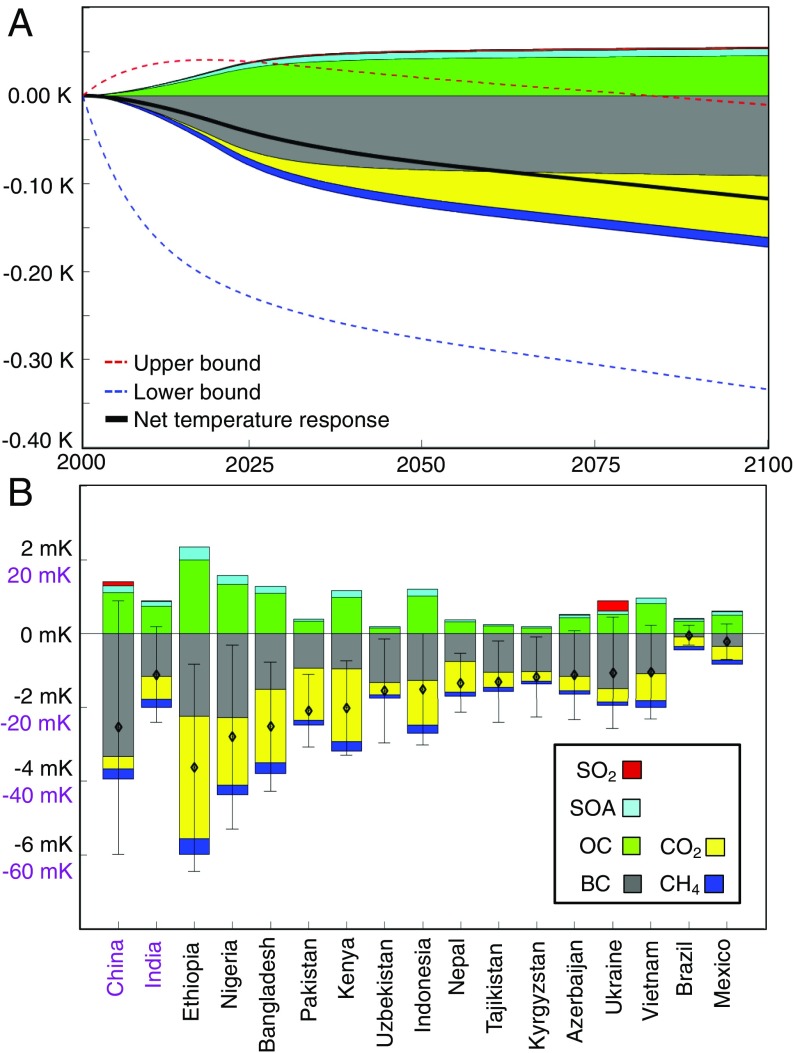

Transient global climate impacts for removal of cookstove emissions, from each emitted species, are shown in Fig. 1. For aerosols, we present impacts of emissions of sulfur dioxide (SO2), primary black carbon (BC), and primary organic carbon (OC), as well as additional secondary organic aerosol (SOA) formed from volatile organic carbon emissions. Fig. 1A shows these contributions to the net transient temperature response. SLCP impacts dominate the response for the first half of the century, whereas the GHG impacts, particularly CO2, become increasingly important by 2100, consistent with previous studies of other types of mitigation (29–31). Cooling caused by removal of the absorptive species (BC, CO2, and CH4) outweighs the warming from removal of reflective aerosols (OC and sulfate, the latter from coal), with BC contributing the most to the surface temperature impact.

Fig. 1.

The global transient surface temperature response to a phasing out of solid fuel cookstove emissions by 2020. Individual colors represent each emitted species’ contribution to the global response. (A) The global mean surface temperature response (net impact shown as solid black line). (B) National contributions to global surface temperature response in 2050 for the countries with the largest contribution, along with Brazil and Mexico for comparison. China’s and India’s contributions are shown in purple on the axis.

The use of adjoint sensitivities allows us to identify the contribution of each country’s emissions to global climate change. Fig. 1B shows countries with the largest contributions of national-scale emissions to the global average surface temperature response in 2050, with the breakdown of each species’ contribution to that impact, along with Brazil and Mexico for comparison. Note that countries with large GHG contributions will have relatively larger overall impacts in later decades than are shown in Fig. 1B, as GHG effects increase, consistent with global-scale trends shown in Fig. 1A; the tabulated transient national-scale contributions for all countries with larger than 5 solid fuel use can be found in Dataset S1. Considering only carbonaceous aerosols, Lacey and Henze (11) highlighted the value of mitigating BC emissions in high-latitude countries, which incur the largest-magnitude cooling response per kilogram of abated BC emission, whereas the removal of coemitted OC in many countries (e.g., Central and South America and parts of Africa) leads to a net warming. Accounting for coemitted GHGs, here we find that in regions wherein residential solid fuel emissions have a large OC component, the climate impact from CO2 and CH4 counteracts the cooling impact of these reflective aerosols. This occurs in African countries that use large amounts of nonrenewable solid fuels (7), as shown by the larger percentage of contribution of CO2 to the net temperature impact in countries such as Ethiopia and Kenya. Fig. 1B also shows the uncertainties in the net global surface temperature response. For several countries (e.g., Ethiopia, Bangladesh, Kenya), the range of temperature impacts spans zero, meaning that removal of these countries’ emissions may have a net warming.

Health.

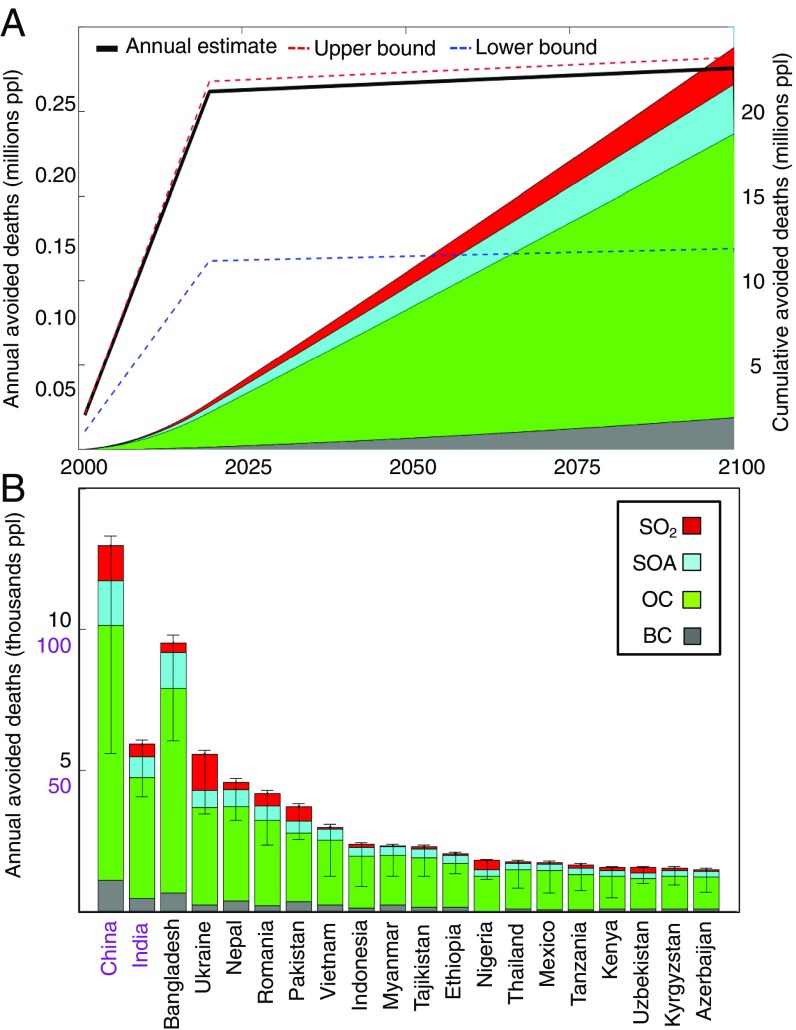

Fig. 2A shows each species’ contribution to cumulative and annual global premature deaths avoided due to changes in ambient PM2.5 from the removal of cookstove emissions. The large increase in annual avoided deaths from 2000 to 2020 is due to the phased emissions reduction. The change in annual avoided premature death from 2020 to 2100 is due to increases in population and changes in the formation of sulfate aerosol caused by shifts in anthropogenic emissions.

Fig. 2.

The global transient premature deaths avoided due to changes in ambient PM2.5 from a phased removal of solid fuel cookstove emissions by 2020. Colors show the species’ contributions to the global response. (A) The annual (solid black line) and speciated cumulative health impact response (colored wedges). (B) National contributions to annual avoided premature deaths in 2050 from changes in ambient PM2.5. China’s and India’s impacts are shown in purple on the axis.

The health impacts in Fig. 2B show that OC is the largest contributor to ambient PM2.5 exposure from cookstove emissions throughout all countries. This plot also highlights the importance of SO2 emissions in countries that use a combination of traditional wood and herbaceous fuels along with coal. The countries with the largest contribution to global premature deaths from exposure to ambient PM2.5 from cookstoves are not necessarily the countries with the highest solid fuel use or number of cookstoves (i.e., Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Kenya). Large ambient health impacts from emissions in countries such as Nepal, Pakistan, and Vietnam are due to transport of PM2.5 over populated regions. In contrast, emissions in countries such as Ukraine and Romania contribute to a large percentage of the global health impact owing to high baseline mortality rates (13).

Cobenefits.

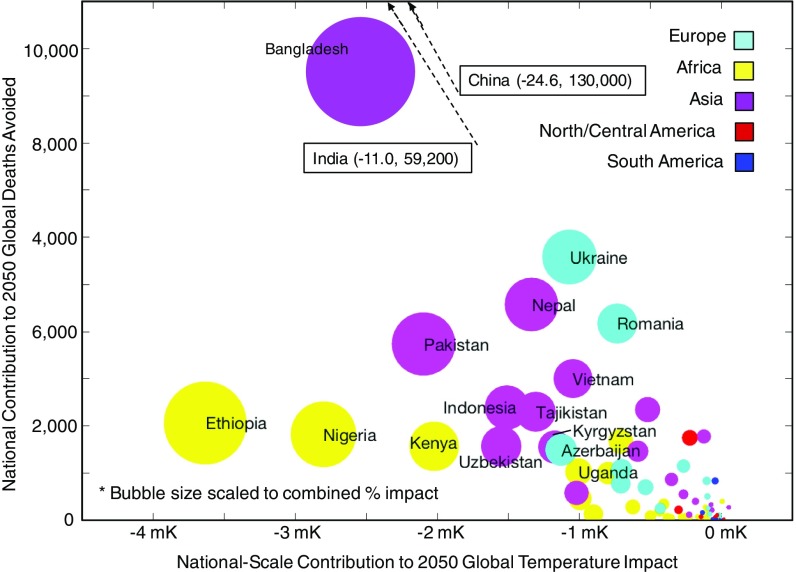

To directly compare climate and ambient air quality impacts, we have calculated each country’s percentage of contribution to global climate and health impacts and plotted these in Fig. 3 on the and axes, respectively. Other studies have compared health and air quality impacts by monetizing both climate and health (e.g., ref. 32). To avoid confounding the estimated transient global impacts with the changing social costs of emissions and statistical values of life, we present both as separate objectives and recognize that country-specific impacts could be monetized in future studies. To illustrate, the impacts plotted here are calculated for 2050, but values for each decade between 2000 and 2050 for 101 countries are provided in Dataset S2. Countries are color coded by continent to highlight differences between regions in terms of the net coimpacts that they exhibit as a response to the phased removal of cookstove emissions. In general, African countries tend to contribute to a larger temperature response due to large amounts of cookstove use and the cooling potential from the removal of the associated GHG emissions. In contrast, the ambient health impacts of emissions from African countries are smaller than in other regions due to the lower population densities. Countries in Southeast Asia tend to contribute to more balanced climate and ambient health impacts in part due to higher population densities and transport of primary aerosol emissions over populated areas, as well as significant solid fuel use and high aerosol radiative efficiencies. The large ambient health impacts from Eastern European emissions reductions are a function of higher baseline mortality rates (13). Also note that impacts of emissions from China and India lie outside the plot axes.

Fig. 3.

National-scale contributions to total global climate and health impacts in 2050 for complete phase-out of cookstove emissions by 2020. The axis shows the change in global surface temperature (relative to 2050 following RCP 4.5). The axis shows the number of premature deaths from the change in ambient PM2.5 concentrations attributed to a country’s individual emission reduction. The bubble size of each country is scaled to the combined percentage of contribution of health and climate impacts for that country.

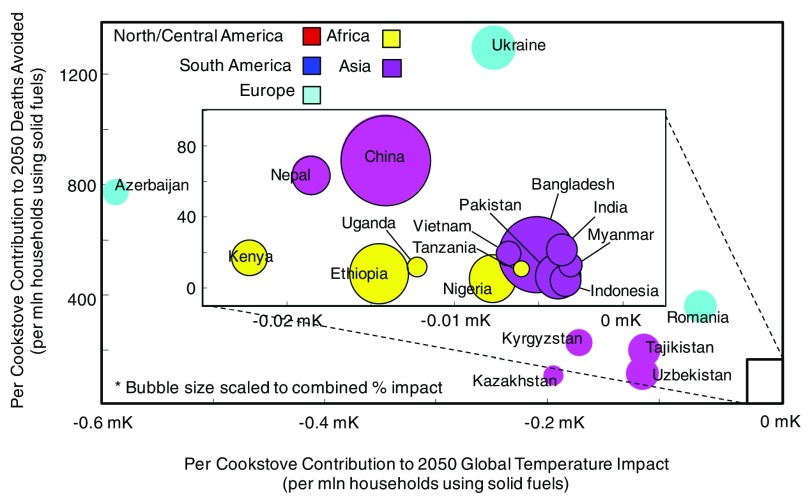

Whereas the overall magnitude of the impacts is important in understanding the drivers of global climate and ambient air quality, of more value with regard to policy, specifically cookstove interventions, are the impacts on a per cookstove basis. We thus next consider (Fig. 4) the national-scale contributions to global climate and air quality impacts divided by the national-scale number of cookstoves, which is estimated using the number of people using solid fuels in 2010 (1) and the household size from the Global Burden of Disease Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Per cookstove (i.e., marginal) impacts are largest for cookstoves in certain regions not typically targeted for cookstove interventions (30), such as those in Central Asia and Eastern Europe, with emissions from Azerbaijan ranking the highest in terms of climate and second highest in terms of health.

Fig. 4.

National-scale per cookstove contributions to climate and health impacts. Inset shows the countries at the lower end of the scale. Individual bubble sizes are colored by continent and scaled to the combined percentage of contribution of net health and climate impacts (China and India bubble size scaled by 1/10 due to the overall magnitude of their impacts).

Discussion and Conclusions

The results presented here show that for the year 2050, the impacts from the phased removal of global solid fuel cookstove emissions are a global average surface temperature cooling of 77 mK (ranging from a 20-mK warming to a 278-mK cooling) and an avoidance of 260,000 (137,00–268,000) annual premature deaths due to ambient PM2.5 exposure, cumulatively avoiding 10.5 (5.55–10.80) million premature deaths from 2000 to 2050. Aerosols contribute 41 to the central estimate of net global cookstove climate impacts by 2050 and alone may be cooling or warming with large uncertainties based on fuel type and aerosol’s climate impacts. However, net climate impacts of cookstove emissions reductions are likely cooling, when considering benefits of curbed GHG emissions, which become increasingly prominent on longer time horizons. National-scale contributions of cookstove emissions to global premature deaths due to ambient PM2.5 exposure are driven by primary organic carbonaceous aerosol.

Emissions from cookstoves in China and India are the largest, and they contribute the most to ambient air quality and climate impacts; however, the role of other countries does not in general always correspond to the magnitude of their emissions. Fig. 5 depicts how ambient air quality and climate benefits of cookstove interventions are modulated by the role of transport of aerosols over populated regions, the combined impacts of absorbing and reflective components of aerosols, the ratio of GHG to aerosol emissions as a function of fuel type, and the magnitude of semi- and indirect climate effects of opposite sign. Several countries (Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Ukraine) rank in the top 20 in terms of their coimpacts without being ranked highly in terms of total population using solid fuels. Despite a smaller amount of cookstove use, intervention programs in these countries are estimated to result in the highest cobenefit per cookstove replaced owing to increased climate impacts of BC due to transport to the Arctic and over snow and the increased number of premature deaths due to high baseline mortality rate in these regions.

Fig. 5.

The top 20 countries ranked in terms of three variables: population using solid fuels for cooking (blue), total net contribution to the global surface temperature change from the emissions from cookstove solid fuel emissions (green), and the total net contribution to global premature deaths from exposure to ambient PM2.5 from cookstove solid fuel emissions (red).

Although this study uses state-of-the-art modeling techniques to estimate climate and health impacts, several assumptions must be made to allow for efficient model calculations. We consider a range of emissions factors for BC to OC, but our estimates do not explicitly consider uncertainties in total carbonaceous emissions (although marginal impacts, to first order, are less sensitive to this type of uncertainty). We attempt to account for this when estimating health impacts by considering a range of satellite-derived PM2.5 datasets (24, 28), but additional assessment of cookstove emissions inventories and resulting PM2.5 concentrations would be valuable (33). Our work only crudely treats SOA formation and is sensitive to uncertainties in emission factors of nonmethane organic compounds (34, 35). New understandings in the roles of SO2 and NOx emissions on SOA formation (e.g., ref. 36) may indicate our SOA estimates are lower bounds. Our methods also use global estimates of aerosol semi- and indirect climate impacts (37) and assume a central BC radiative forcing from Bond et al. (38) that has been suggested to be 27 too large (39). Our adjoint sensitivities were calculated using a single year of meteorology (2009) that may not reflect a climatological mean, although error bounds of our radiative forcing estimates do draw from comparisons of multiyear modeling studies. Future work may be able to extend the source attribution techniques used in our study for direct RF to indirect effects and account for future changes in meteorology. For the health impacts, our assumption that present-day mortality rates persist throughout the scenarios may lead to overestimates, as recent work predicts that baseline mortality rates in the top countries impacted by changes in solid fuel use may decrease by 30 in 2050 (40). Finally, we have focused on the impact of cookstove emissions under an illustrative yet simplistic phase-out scenario. If instead cookstoves were replaced with tier 1 or tier 2 solid-fuel cookstoves, we would expect a 28 and 56 reduction, respectively, in health and climate impacts from this replacement, given the emissions factors for these stoves (41). Tier 3 and tier 4 stoves require access to different fuel sources and a more comprehensive integrated assessment of life-cycle impacts. Nonetheless, despite the stated uncertainties and assumptions, this work provides information to decision makers to evaluate climate and ambient health impacts of current and ongoing cookstove interventions (cleancookstoves.org/about/news/11-20-2014-market-enabling-roadmap-phase-2-2015-2017.html).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The research described in the article has been funded wholly or in part by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)’s STAR program through Grant 83521101, although it has not been subjected to any EPA review and therefore does not necessarily reflect the views of the Agency, and no official endorsement should be inferred. This work is possible through National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Air Quality Applied Sciences Team (NNX11AI54G), NASA Health and Air Quality Applied Sciences Team (NNX16AQ26G), and support from NASA High-End Computing Capability facilities.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. D.T.S. is a Guest Editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1612430114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Bonjour S, et al. Solid fuel use for household cooking: Country and regional estimates for 1980–2010. Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121(7):784–790. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adair-Rohani H, et al. Burning Opportunity: Clean Household Energy for Health, Sustainable Development, and Wellbeing of Women and Children. WHO; Geneva: 2016. Tech Rep. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anenberg SC, et al. Cleaner cooking solutions to achieve health, climate, and economic cobenefits. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47(9):3944–3952. doi: 10.1021/es304942e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chafe ZA, et al. Household cooking with solid fuels contributes to ambient PM2.5 air pollution and the burden of disease. Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122(12):1314–1320. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1206340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forouzanfar MH, et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks in 188 countries, 1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386(10010):2287–2323. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00128-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lelieveld J, Evans JS, Fnais M, Giannadaki D, Pozzer A. The contribution of outdoor air pollution sources to premature mortality on a global scale. Nature. 2015;525(7569):367–371. doi: 10.1038/nature15371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bailis R, Drigo R, Ghilardi A, Masera O. The carbon footprint of traditional woodfuels. Nat Clim Change. 2015;5(3):266–272. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Myhre G, et al. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge Univ Press; United Kingdom: 2013. Anthropogenic and natural radiative forcing. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Unger N, et al. Attribution of climate forcing to economic sectors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(8):3382–3387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906548107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kodros JK, et al. Uncertainties in global aerosols and climate effects due to biofuel emissions. Atmos Chem Phys Discuss. 2015;15(7):10199–10256. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lacey F, Henze D. Global climate impacts of country-level primary carbonaceous aerosol from solid-fuel cookstove emissions. Environ Res Lett. 2015;10(11):114003. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Butt EW, et al. The impact of residential combustion emissions on atmospheric aerosol, human health and climate. Atmos Chem Phys Discuss. 2015;15(14):20449–20520. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee CJ, et al. Response of global particulate-matter-related mortality to changes in local precursor emissions. Environ Sci Technol. 2015;49(7):4335–4344. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b00873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henze DK, et al. Spatially refined aerosol direct radiative forcing efficiencies. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46(17):9511–9518. doi: 10.1021/es301993s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shindell D, Faluvegi G. Climate response to regional radiative forcing during the twentieth century. Nat Geosci. 2009;2(4):294–300. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Punger EM, West JJ. The effect of grid resolution on estimates of the burden of ozone and fine particulate matter on premature mortality in the USA. Air Qual Atmos Health. 2013;6(3):563–573. doi: 10.1007/s11869-013-0197-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shindell DT. Evaluation of the absolute regional temperature potential. Atmos Chem Phys. 2012;12(17):7955–7960. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joos F, et al. Carbon dioxide and climate impulse response functions for the computation of greenhouse gas metrics: A multi-model analysis. Atmos Chem Phys. 2013;13(5):2793–2825. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aamaas B, Peters GP, Fuglestvedt JS. Simple emission metrics for climate impacts. Earth Syst Dynam. 2013;4(1):145–170. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boucher O, et al. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge Univ Press; Cambridge, United Kingdom: 2013. Clouds and aerosols. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lamarque JF, et al. The Atmospheric Chemistry and Climate Model Intercomparison Project (ACCMIP): Overview and description of models, simulations and climate diagnostics. Geosci Model Dev. 2013;6(1):179–206. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roden CA, et al. Laboratory and field investigations of particulate and carbon monoxide emissions from traditional and improved cookstoves. Atmos Environ. 2009;43(6):1170–1181. [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacCarty N, Still D, Ogle D. Fuel use and emissions performance of fifty cooking stoves in the laboratory and related benchmarks of performance. Energy Sustainable Dev. 2010;14(3):161–171. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brauer M, et al. Ambient air pollution exposure estimation for the global burden of disease 2013. Environ Sci Technol. 2016;50(1):79–88. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b03709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN), Columbia University, and Centro Internacional de Agricultura Tropical (CIAT) 2005. Gridded Population of the World, Version 3 (GPWv3): Population Density Grid, Future Estimates [NASA Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center (SEDAC), Palisades, NY]

- 26.Burnett RT, et al. An integrated risk function for estimating the global burden of disease attributable to ambient fine particulate matter exposure. Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122(4):397–403. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1307049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lozano R, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2095–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Donkelaar A, et al. Global estimates of fine particulate matter using a combined geophysical-statistical method with information from satellites, models, and monitors. Environ Sci Technol. 2016;50(7):3762–3772. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b05833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramanathan V, Xu Y. The Copenhagen Accord for limiting global warming: Criteria, constraints, and available avenues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:8055–8062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002293107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) 2011. Near-Term Climate Protection and Clean Air Benefits Actions for Controlling Short-Lived Climate Forcers: A UNEP Synthesis Report. [United Nations Office at Nairboi (UNON) Publishing ServicesSection, Nairobi]

- 31.Smith SJ, Mizrahi A. Near-term climate mitigation by short-lived forcers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(35):14202–14206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308470110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shindell DT, Lee Y, Faluvegi G. Climate and health impacts of US emissions reductions consistent with 2 °C. Nat Clim Change. 2016;6(5):503–507. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Winijkul E, Fierce L, Bond TC. Emissions from residential combustion considering end-uses and spatial constraints: Part I, methods and spatial distribution. Atmos Environ. 2015;125(A):126–139. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grieshop AP, Marshall JD, Kandlikar M. Health and climate benefits of cookstove replacement options. Energy Policy. 2011;39(12):7530–7542. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Streets DG, et al. An inventory of gaseous and primary aerosol emissions in Asia in the year 2000. J Geophys Res Atmos. 2003;108(D21):8809. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu L, et al. Effects of anthropogenic emissions on aerosol formation from isoprene and monoterpenes in the southeastern United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(1):37–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1417609112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.UNEP, WMO . Integrated Assessment of Black Carbon and Tropospheric Ozone. UNEP; 2011. Tech Rep. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bond TC, et al. Bounding the role of black carbon in the climate system: A scientific assessment. J Geophys Res Atmos. 2013;118(11):5380–5552. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang R, et al. Estimation of global black carbon direct radiative forcing and its uncertainty constrained by observations. J Geophys Res Atmos. 2016;121(10):5948–5971. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Frederick S. Pardee Center for International Futures (2015) International Futures (IFs) Modeling System, Version 7.24 (Josef Korbel School of International Studies, University of Denver, Denver)

- 41.Jetter J, et al. Pollutant emissions and energy efficiency under controlled conditions for household biomass cookstoves and implications for metrics useful in setting international test standards. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46(19):10827–10834. doi: 10.1021/es301693f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bond TC, et al. Historical emissions of black and organic carbon aerosol from energy-related combustion, 1850–2000. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2007;21(2):GB2018. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lamarque J-F, et al. Historical (1850–2000) gridded anthropogenic and biomass burning emissions of reactive gases and aerosols: Methodology and application. Atmos Chem Phys. 2010;10(15):7017–7039. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bey I, et al. Global modeling of tropospheric chemistry with assimilated meteorology: Model description and evaluation. J Geophys Res Atmos. 2001;106(D19):23073–23095. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Philip S, et al. Spatially and seasonally resolved estimate of the ratio of organic mass to organic carbon. Atmos Environ. 2014;87:34–40. [Google Scholar]

- 46.MacCarty N, Ogle D, Still D, Bond T, Roden C. A laboratory comparison of the global warming impact of five major types of biomass cooking stoves. Energy Sustainable Dev. 2008;12(2):56–65. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Henze D, Seinfeld J. Development of the adjoint of GEOS-Chem. Atmos Chem Phys. 2007;6(5):10591–10648. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spurr RJD, Kurosu TP, Chance KV. A linearized discrete ordinate radiative transfer model for atmospheric remote-sensing retrieval. J Quant Spectrosc Radiat Transf. 2001;68(6):689–735. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shindell DT, et al. Radiative forcing in the ACCMIP historical and future climate simulations. Atmos Chem Phys. 2013;13(6):2939–2974. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kasoar M, et al. Regional and global temperature response to anthropogenic SO2 emissions from China in three climate models. Atmos Chem Phys. 2016;16(15):9785–9804. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith SJ, Wigley TML. Multi-gas forcing stabilization with the MiniCAM. Energy J. 2006;3(Special Issue):373–391. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moss RH, et al. The next generation of scenarios for climate change research and assessment. Nature. 2010;463(7282):747–756. doi: 10.1038/nature08823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sand M, et al. The Arctic response to remote and local forcing of black carbon. Atmos Chem Phys. 2013;13(1):211–224. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stohl A, et al. Evaluating the climate and air quality impacts of short-lived pollutants. Atmos Chem Phys. 2015;15(18):10529–10566. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dentener F, et al. The impact of air pollutant and methane emission controls on tropospheric ozone and radiative forcing: CTM calculations for the period 1990-2030. Atmos Chem Phys. 2005;5(7):1731–1755. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fiore A, West J, Horowitz L, Naik V, Schwarzkopf M. Characterizing the tropospheric ozone response to methane emission controls and the benefits to climate and air quality. J Geophys Res. 2008;113:D08307. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boucher O, Reddy MS. Climate trade-off between black carbon and carbon dioxide emissions. Energy Policy. 2008;36(1):193–200. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang R, et al. Exposure to ambient black carbon derived from a unique inventory and high-resolution model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(7):2459–2463. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318763111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.