Significance

Hybrid seed lethality has been recognized and addressed by a long-standing tradition of plant-breeding research. Nevertheless, its role in evolution and speciation has been underestimated. In this study, hybrid seed lethality between Arabidopsis lyrata and Arabidopsis arenosa, two model species of growing interest in the scientific community, was investigated. This study shows that endosperm defects are sufficient to explain the direction of gene flow between the two wild species, suggesting an important role of this hybridization barrier in plant speciation. In addition, we show that natural polyploidization is involved in breaking down hybridization barriers, not only establishing them, as implied by the traditional “triploid block” concept. Our data suggest that polyploidy-mediated hybrid seed rescue, long known in artificial crosses, could play an important role in plant evolution.

Keywords: interspecies hybrid seed failure, Arabidopsis, reproductive isolation, endosperm cellularization, EBN

Abstract

Based on the biological species concept, two species are considered distinct if reproductive barriers prevent gene flow between them. In Central Europe, the diploid species Arabidopsis lyrata and Arabidopsis arenosa are genetically isolated, thus fitting this concept as “good species.” Nonetheless, interspecific gene flow involving their tetraploid forms has been described. The reasons for this ploidy-dependent reproductive isolation remain unknown. Here, we show that hybridization between diploid A. lyrata and A. arenosa causes mainly inviable seed formation, revealing a strong postzygotic reproductive barrier separating these two species. Although viability of hybrid seeds was impaired in both directions of hybridization, the cause for seed arrest differed. Hybridization of A. lyrata seed parents with A. arenosa pollen donors resulted in failure of endosperm cellularization, whereas the endosperm of reciprocal hybrids cellularized precociously. Endosperm cellularization failure in both hybridization directions is likely causal for the embryo arrest. Importantly, natural tetraploid A. lyrata was able to form viable hybrid seeds with diploid and tetraploid A. arenosa, associated with the reestablishment of normal endosperm cellularization. Conversely, the defects of hybrid seeds between tetraploid A. arenosa and diploid A. lyrata were aggravated. According to these results, we hypothesize that a tetraploidization event in A. lyrata allowed the production of viable hybrid seeds with A. arenosa, enabling gene flow between the two species.

According to the biological species concept, reproductive isolation is a major criterion for defining two distinct species (1). Nevertheless, hybridization has long been recognized to play an important role in plant evolution, with many reported cases of related species that, either punctually or continuously in their life history, have experienced gene flow, leading to introgression of adaptive traits or hybrid speciation (2–9). Thus, the “tree of life” is considered more as a complex network than an actual tree (10, 11). Whereas gene flow between previously isolated species can occur after a secondary contact (5, 12), the mechanisms contributing to this gene flow are largely unknown.

The evolutionary relationships of the Arabidopsis genus may also be depicted as a network rather than a dichotomizing tree (9). For example, the two tetraploid species Arabidopsis suecica and Arabidopsis kamchatica both have a hybrid (allopolyploid) origin involving Arabidopsis thaliana and Arabidopsis arenosa as parental species in A. suecica and Arabidopsis lyrata and Arabidopsis halleri ssp. gemmifera in A. kamchatica (13, 14). Gene flow has also been observed between A. lyrata and A. arenosa (15, 16). These two species, which are believed to have originated and radiated in Central Europe around 2 Mya (17), both exist in a diploid and tetraploid form. Diploid A. lyrata colonized central and northern Europe as well as northern America, whereas the tetraploid form is limited to eastern Austria (15). For A. arenosa, the diploids are mainly found in the Carpathians and southeastern Europe, whereas the tetraploids occupy central and northern Europe (15, 18, 19). Diploid A. lyrata and A. arenosa are considered “good species” because they are genetically and phenotypically distinct and no past or recent gene flow can be detected between them (15, 16). Although the geographical separation between these species can partly explain this observation, it is likely that other reproductive barriers also contributed to the divergence between diploid A. lyrata and A. arenosa. In contrast, two main hybridization zones between tetraploid A. lyrata and tetraploid A. arenosa have been described in Austria (15, 16). It has been suggested that the gene flow between tetraploid A. lyrata and A. arenosa is bidirectional (16). Another study, however, found that, although tetraploid A. lyrata was highly introgressed by A. arenosa in the contact zones, the tetraploid A. arenosa populations showed a low hybrid index in the same region (15). Based on these data, unidirectional gene flow from A. arenosa to tetraploid A. lyrata was proposed, and the authors concluded that tetraploid A. lyrata originated and spread in Austria as a consequence of an original hybridization of A. arenosa with A. lyrata (15). Whether this original hybridization event occurred between diploids, tetraploids, or in an interploidy manner remains unresolved.

The presence of interspecific gene flow involving tetraploid, but not diploid A. lyrata, raises the question whether polyploidization of A. lyrata actually facilitated the hybridization success with A. arenosa. Indeed, even though new polyploids are often reproductively isolated from their diploid congeners, referred as the “triploid block” (20), polyploidization is also associated with the bypass of interspecific reproductive barriers (21–25). Postzygotic interspecific reproductive barriers rely on similar mechanisms as the triploid block; both affect hybrid seed survival as a consequence of endosperm developmental failure. The endosperm of most angiosperms is a triploid tissue that develops after fertilization of the homodiploid central cell to support embryo growth (26). It is a dosage-sensitive tissue, which strictly requires a relative maternal:paternal genome ratio of 2:1 to develop correctly (27, 28). Interploidy hybridizations disrupt the 2:1 ratio in the endosperm, leading to asymmetric endosperm developmental failure depending on the direction of hybridization. Increased ploidy of the paternal parent causes delayed or failed endosperm cellularization, whereas increased maternal ploidy induces precocious endosperm cellularization (29–31). Endosperm cellularization is a major developmental transition that, if impaired, leads to embryo arrest and seed lethality (32–34). As a consequence, interploidy hybrid seeds are usually inviable (29–31, 35, 36). Interestingly, very similar nonreciprocal seed phenotypes are also observed in interspecies hybrid seeds, even between species of same ploidy levels (36–39). This finding suggests that species, despite having the same ploidy level, differ in their relative genome dosage, resulting in unbalanced contributions of cellularization factors leading to cellularization failure. Increasing the ploidy level of the species with predicted lower genome dosage leads to increased hybrid seed viability, confirming the quantitative character of the interspecies hybridization barrier (21, 25).

According to the endosperm balance number (EBN) hypothesis, the effective ploidy of a species must be in a 2:1 maternal to paternal ratio in the endosperm to allow normal endosperm development (21–23, 40). It has been proposed that species can have different effective ploidies, explaining the quantitative nature of hybrid seed failure. In the Solanum genus (21) and in several other genera, like Impatiens (22) and Trifolium (23), each species was assigned a numerical effective ploidy (or EBN). Using this concept, the hybridization success between related species can be predicted; species with similar effective ploidy or EBN can successfully hybridize, whereas species with different EBN give inviable hybrid seeds, unless the ploidy of the lower EBN species is increased to match the EBN of the other species (21, 40). Based on the assigned EBNs, these studies were accurately able to predict the viability of artificial interspecific crosses. It remains unresolved, however, whether EBN divergence and its bypass by polyploidization is important for hybrid seed viability in the wild and whether it regulates gene flow between wild species.

Reciprocal crosses between diploid A. lyrata and diploid A. arenosa exhibit impaired hybrid seed viability in a nonreciprocal manner (41); however, the cause for this barrier has not been identified. In this work, we tested the hypothesis that both species are reproductively isolated by an endosperm-based reproductive barrier and thus differ in their EBN. Our data add strong support to this hypothesis; in incompatible hybrid cross combinations, endosperm cellularization is either precocious, delayed, or does not occur at all. Increasing the ploidy of A. lyrata is sufficient to overcome this hybridization barrier, assigning A. lyrata a lower EBN compared with A. arenosa. Our data let us to propose that the tetraploidization of A. lyrata initiated the gene flow between A. lyrata and A. arenosa observed in Central Europe.

Results

Hybridizations of Diploid A. lyrata and A. arenosa Lead to Mostly Inviable Seeds.

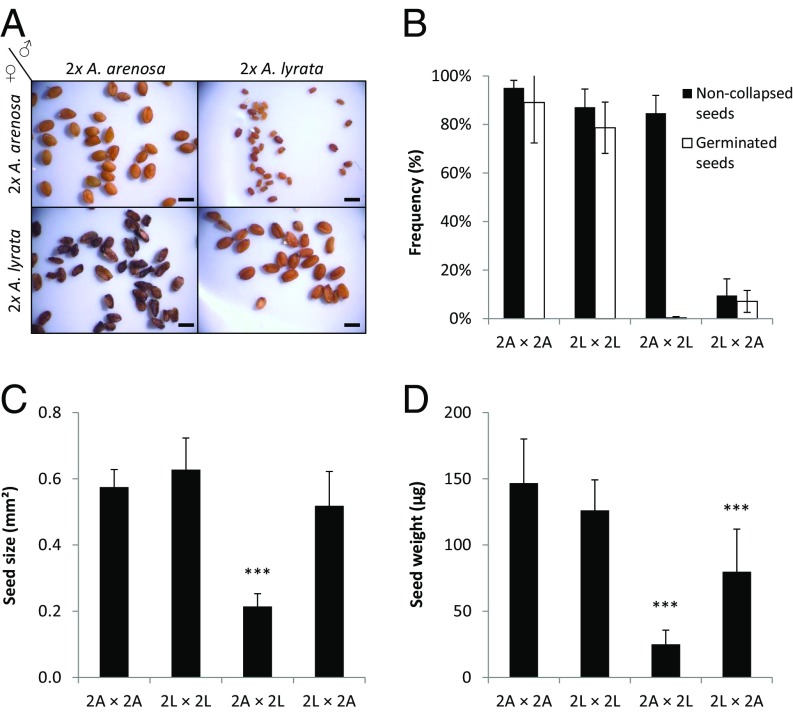

To test the hypothesis that the central European diploid populations of A. lyrata and A. arenosa are reproductively isolated by a postzygotic barrier acting in the endosperm, we performed manual reciprocal crosses between these two diploid species (for population details, Materials and Methods and Fig. S1). Seeds derived after hybridizations of A. lyrata seed parents with A. arenosa pollen donors (denoted A. lyrata × A. arenosa) were dark and shriveled, whereas the reciprocal hybrid seeds were severely reduced in size but appeared normally shaped compared with nonhybrid seeds (Fig. 1A). However, independent of the seed phenotype, hybrid seeds of both cross directions largely failed to germinate (Fig. 1B). A. lyrata × A. arenosa seeds were of similar size compared with the average of parental seeds (Fig. 1C, midparent value) (42), but weighed significantly less (Fig. 1D). In the reciprocal A. arenosa × A. lyrata cross, seeds were significantly smaller and weighed significantly less compared with the midparent value (Fig. 1 C and D).

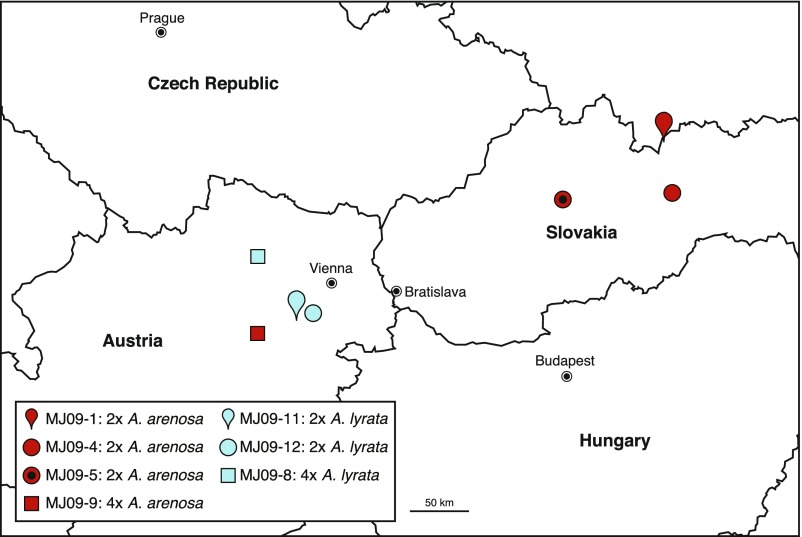

Fig. S1.

Locations of populations used in this study. Red and blue symbols represent populations of diploid and tetraploid Arabidopsis arenosa and diploid and tetraploid Arabidopsis lyrata, respectively. For more information, see Table S2. The map was modified from Google Maps.

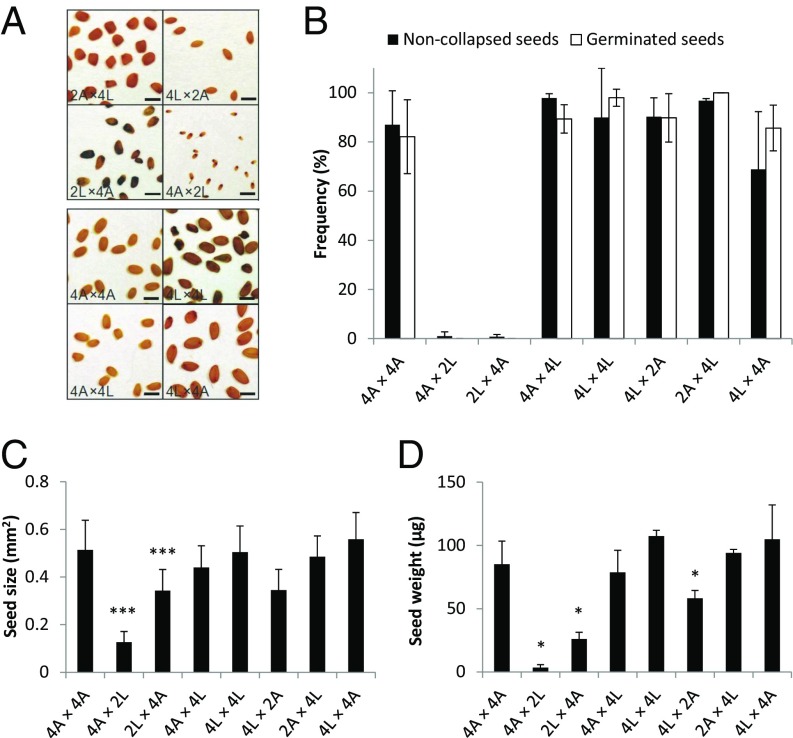

Fig. 1.

Asymmetric defects in diploid A. lyrata × A. arenosa reciprocal hybrid seeds cause impaired viability. (A) Pictures of seeds obtained from intra- and interspecific controlled crosses between 2x A. lyrata and 2x A. arenosa. Seed parents are indicated; (Left) seed parent (♀); (Upper) pollen donor (♂). (Scale bars, 1 mm.) (B) Seed viability of indicated crosses given as the rate of noncollapsed and germinated seeds. The directionality of the cross is indicated as seed parent (♀) × pollen donor (♂). The germination rate for 2x A. arenosa × 2x A. lyrata seeds is 0%. (C) Seed size for indicated crosses. (D) Seed weight for indicated crosses. 2A: 2x A. arenosa; 2L: 2x A. lyrata. Error bars represent SD between cross replicates (>5 replicates for each sample). ***P < 0.001 compared with the midparent value, as identified by a t test.

Nonreciprocal Endosperm Defects Cause Diploid A. lyrata/A. arenosa Hybrid Seed Inviability.

The cross-direction–dependent phenotype of these hybrid seeds resembles those observed in interploidy crosses (29–31) as well as other interspecies crosses (36, 38, 43). Delayed or absence of endosperm cellularization or precocious cellularization has been linked to the inviability of interploidy and interspecific hybrid seeds (36, 38, 43). We therefore performed a detailed analysis of seed development and the endosperm cellularization phenotype in A. lyrata × A. arenosa reciprocal hybrids.

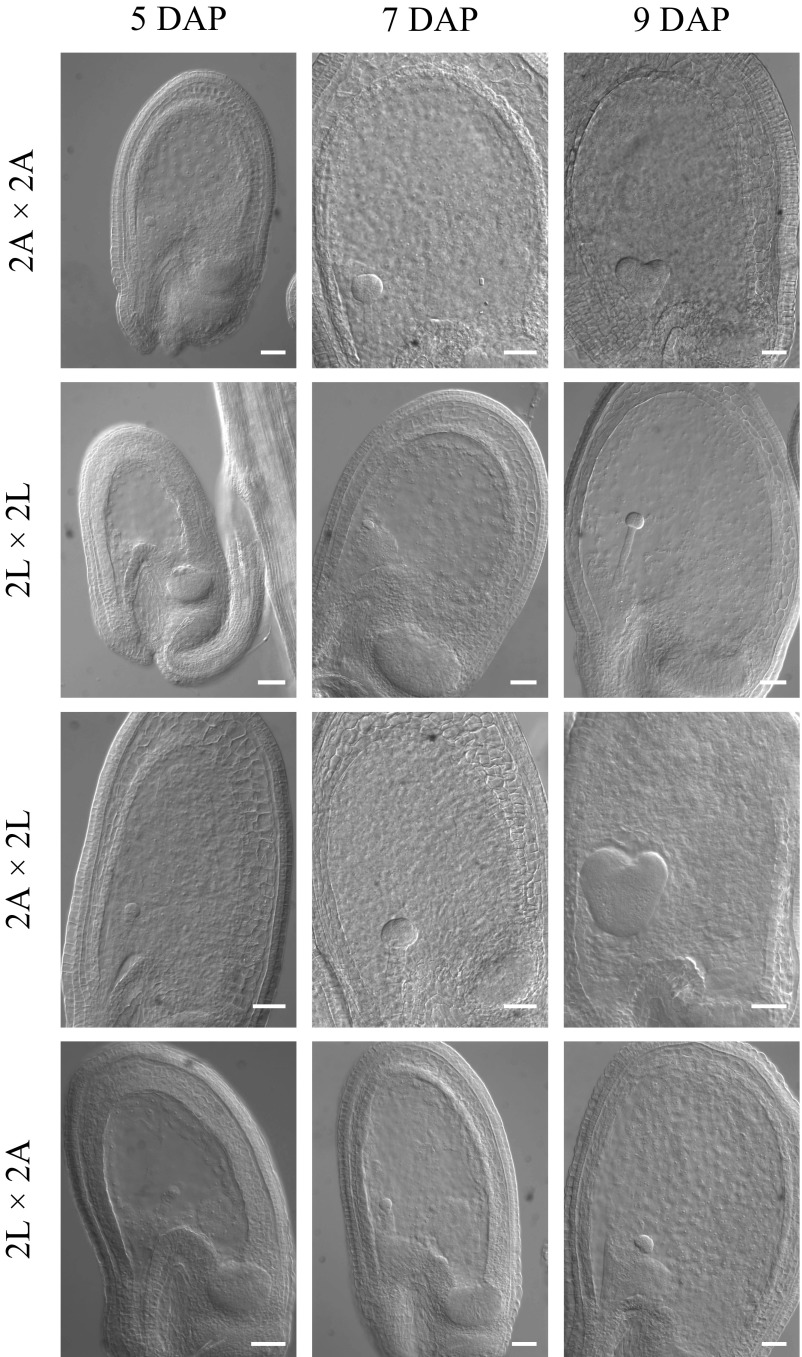

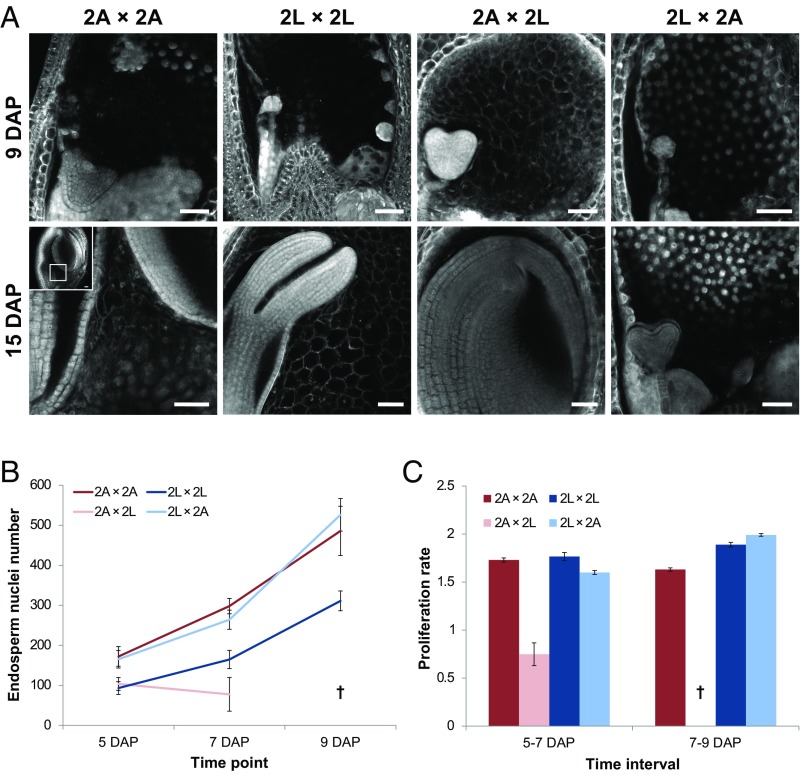

Diploid (2x) A. lyrata seeds developed at a slower pace compared with 2x A. arenosa seeds, as revealed by monitoring embryo development at defined time points (Fig. S2). However, the endosperm of both species was still syncytial at 9 d after pollination (DAP) (Fig. 2A). In contrast, at 9 DAP the A. arenosa × A. lyrata hybrid endosperm was fully cellularized, suggesting a shortened syncytial phase and an earlier onset of cellularization (Fig. 2A). In contrast, the endosperm of A. lyrata × A. arenosa hybrid seeds was still syncytial at 15 DAP, when the endosperms of both parents were cellularized. Cellularization failure correlated with a delay in embryo development: when the embryo of the parents had reached at least the early bent cotyledon stage, the A. lyrata × A. arenosa hybrid embryos were still at the heart stage.

Fig. S2.

Early seed development in diploid A. lyrata, A. arenosa, and reciprocal hybrids. The microscopy pictures show cleared seeds where the embryo and endosperm nuclei are visible. The directionality of the cross is indicated seed parent (♀) × pollen donor (♂). 2A: 2x A. arenosa; 2L: 2x A. lyrata. (Scale bars, 50 µm.)

Fig. 2.

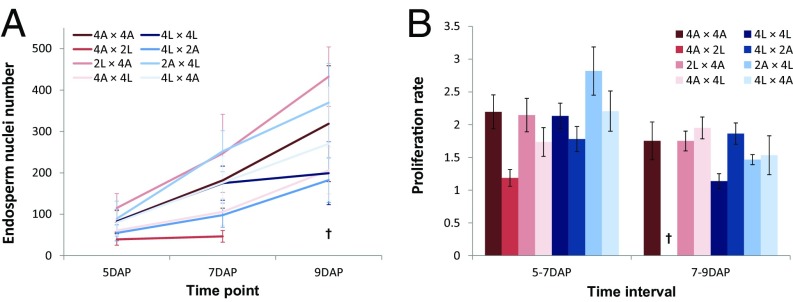

Impaired viability of diploid A. lyrata × A. arenosa reciprocal hybrid seeds is correlated with asymmetric endosperm cellularization defects, but not with endosperm proliferation. (A) Feulgen-stained seeds of A. lyrata, A. arenosa, and reciprocal hybrids are depicted. Early (9 DAP) and late (15 DAP) time points are displayed. At 15 DAP, A. arenosa seeds (2A × 2A) are very large and mostly occupied by the embryo. For a better display of the remaining endosperm, the larger inlay represents the entire seed and the smaller inlay represents the zoomed-in endosperm region. Images shown in this figure are representative for a total number of observed seeds of at least 20 per biological replicate (three replicates). (Scale bars, 50 µm.) (B) Endosperm proliferation was assessed by measuring endosperm nuclei number at 5, 7, and 9 DAP, represented as absolute endosperm nuclei number. (C) Proliferation rate was calculated as the ratio of nuclei number between 5 and 7 DAP and between 7 and 9 DAP. 2A: 2x A. arenosa; 2L: 2x A. lyrata. Parental species are represented by dark red (A. arenosa) and dark blue (A. lyrata) colors and reciprocal hybrids by light shades (light red and light blue for A. arenosa × A. lyrata and A. lyrata × A. arenosa, respectively). The cross (†) at 9 DAP indicates that endosperm nuclei for A. arenosa × A. lyrata were not detectable. In B, error bars represent SD between three biological replicates (n = 5 seeds per sample). In C, the error bars were calculated as follows: ratio value × [(coefficient of variationtime22)+(coefficient of variationtime12)]/2.

To test whether differences in endosperm cellularization were connected to differences in endosperm proliferation, we assessed endosperm proliferation in parental seeds by counting endosperm nuclei at 5, 7, and 9 DAP. Consistent with phenotypic observations, A. lyrata had fewer endosperm nuclei, corresponding to one cycle of endosperm nuclear division less at 5 DAP in A. lyrata compared with A. arenosa (Fig. 2B). However, after 5 DAP the rate of proliferation was similar between the two species (Fig. 2C), suggesting that the initial endosperm proliferation in A. lyrata is either delayed or slower than in A. arenosa. In contrast, the number of endosperm nuclei in A. lyrata × A. arenosa hybrid seeds was substantially higher than that of the maternal A. lyrata parent at all analyzed time points (Fig. 2B), whereas the proliferation rate in hybrid seeds was similar to the maternal parent (Fig. 2C), suggesting that the difference in nuclei number is a consequence of a delayed or slower onset of endosperm proliferation in the maternal A. lyrata parent compared with the hybrid. In contrast, A. arenosa × A. lyrata hybrid endosperm started to degenerate after 5 DAP and proliferation could thus not be observed. The total nuclei number at 5 DAP was comparable to the paternal A. lyrata parent. Taken together, these data suggest that hybrid endosperm cellularization timing is not coupled to endosperm proliferation, and that both processes are independently genetically controlled.

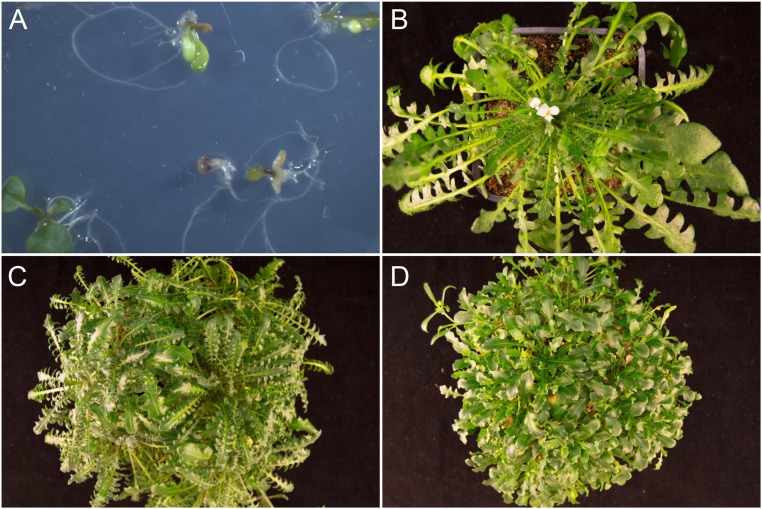

Previous studies have implicated endosperm cellularization failure as a primary cause for hybrid embryo and seed arrest (29–31, 37, 38, 43). To test the hypothesis that A. lyrata × A. arenosa hybrid embryo arrest is causally connected to abnormal endosperm cellularization, we rescued hybrid embryos by dissecting them from the seeds and growing them in vitro in embryo-supporting culture. Dissected embryos survived at a higher rate than when germinated from seeds (54% vs. <10%, respectively; n = 29 dissected embryos). Seedlings regenerated from this experiment were viable and developed into healthy adult hybrids (Fig. S3 A and B) with a phenotype that was intermediate between the dark green, waxy serrate leaves of the parental A. arenosa accession and the lighter green, lobed leaves of the A. lyrata accession used for this cross (Fig. S3 B–D). In vitro survival of hybrid embryos strongly supports the hypothesis that endosperm failure is the primary cause for hybrid seed lethality.

Fig. S3.

Viable A. lyrata × A. arenosa hybrid plants obtained from in vitro embryo rescue. (A) Three-week-old A. lyrata × A. arenosa seedlings grown on MS plate. (B) Fully grown A. lyrata × A. arenosa plant transferred to soil. (C) Fully grown A. arenosa plant. (D) Fully grown A. lyrata plant.

We thus conclude that endosperm cellularization defects are responsible for the failure of 2x A. lyrata × 2x A. arenosa reciprocal hybrid seeds and that endosperm cellularization and endosperm proliferation can be uncoupled.

Increased Ploidy of A. lyrata and A. arenosa Impacts Postzygotic Reproductive Barrier Strength.

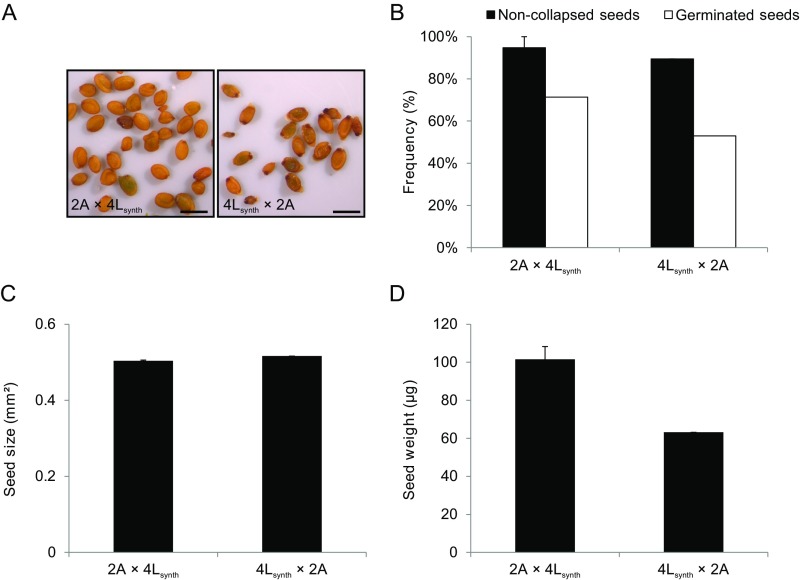

In contrast to diploid populations, natural populations of tetraploid A. lyrata and A. arenosa hybridize (15, 16). We aimed to test the hypothesis that polyploidization impacts the postzygotic hybridization barrier and thus may explain gene flow between the two species. We therefore performed reciprocal crosses between diploids and natural tetraploids of the two species in all possible combinations (Fig. 3A and Fig. S4).

Fig. 3.

Increased ploidy of A. lyrata yields viable hybrid seeds. (A) Pictures of seeds obtained from intra- and interspecific controlled crosses between 2x, 4x A. lyrata and 2x, 4x A. arenosa. The directionality of the cross is indicated seed parent (♀) × pollen donor (♂). (Scale bars, 1 mm.) (B) Seed viability of interploidy interspecific crosses was measured by the rate of noncollapsed and germinated seeds. (C) Seed size for indicated crosses. (D) Seed weight for indicated crosses. Error bars represent SD between cross replicates (≥3 replicates for each cross except 2A × 4L, 2 replicates). Significant differences (*P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001) compared with the midparent value, as identified by a t test. 2A: 2x A. arenosa; 2L: 2x A. lyrata; 4A: 4x A. arenosa; 4L: 4x A. lyrata.

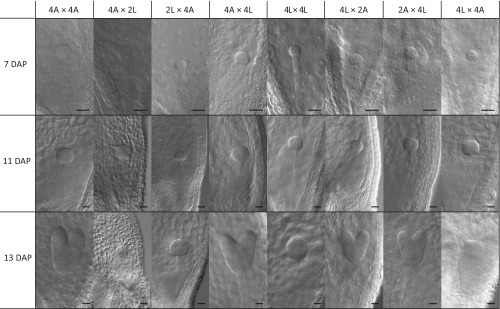

Fig. S4.

Early embryo development in diploid and tetraploid A. lyrata, A. arenosa, and reciprocal hybrids. The microscopy pictures show cleared seeds where the embryo and endosperm nuclei are visible. Embryo stages depicted are representative for the average embryo stage observed. The directionality of the cross is indicated seed parent (♀) × pollen donor (♂). 2A: 2x A.arenosa; 2L: 2x A. lyrata; 4A: 4x A. arenosa; 4L: 4x A. lyrata. (Scale bars, 20 µm.)

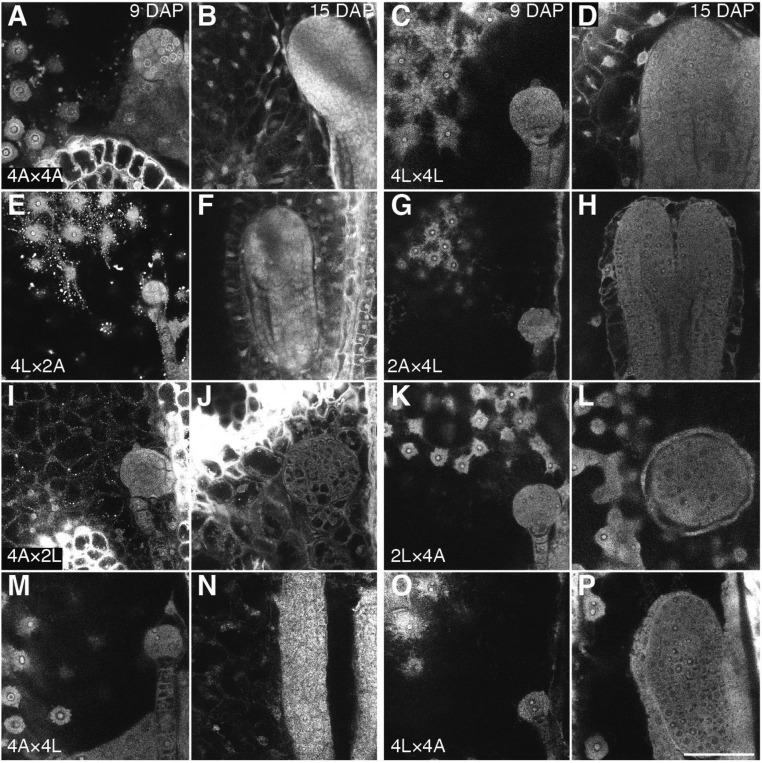

Strikingly, when A. lyrata natural tetraploids (4x) were reciprocally crossed with 2x A. arenosa, seeds were fully viable in both cross directions, as judged by seed shape and germination tests (Fig. 3 A and B). The size of 2x A. arenosa × 4x A. lyrata hybrid seeds was similar to the midparent value, whereas 4x A. lyrata × 2x A. arenosa seeds were significantly smaller (Fig. 3D). Hybrid seed viability was associated with restored endosperm cellularization, occurring around 15 DAP in both cross directions, similar to the tetraploid parents (Fig. 4 A–H and Fig. S4). In both cross directions the endosperm was syncytial at 9 DAP, revealing restored cellularization timing in 2x A. arenosa × 4x A. lyrata hybrid seeds. Endosperm proliferation rate in 4x A. lyrata × 2x A. arenosa and 2x A. arenosa × 4x A. lyrata viable hybrids was either not affected or higher than in the parents respectively (Fig. 5), making it likely that restored endosperm cellularization rather than proliferation rate caused hybrid seed rescue. Because natural populations of 4x A. lyrata and 4x A. arenosa hybridize in the wild, the observed hybrid seed rescue could be a consequence of introgressed A. arenosa loci into the natural 4x A. lyrata (15). To test this hypothesis, we generated synthetic 4x A. lyrata from the diploid populations used in this study, for which no known gene flow with A. arenosa has been observed (15, 16; and data shown in this study). The synthetic (synth) 4x A. lyrata behaved like the natural 4x A. lyrata when reciprocally crossed with 2x A. arenosa (Fig. S5A). Seeds were mostly viable in both cross directions, and their size was similar to the parental values, even though 4x A. lyratasynth × 2x A. arenosa seeds weighed less (Fig. S5 B–D). These data reveal that tetraploidization of A. lyrata is sufficient to circumvent the endosperm-based hybridization barrier with the diploid A. arenosa.

Fig. 4.

Rescue of hybrid seeds involving tetraploid A. lyrata is associated with restored endosperm cellularization. Feulgen-stained seeds of tetraploid A. lyrata, A. arenosa, and interploidy interspecific hybrids are depicted as follow: (A and B) 4x A. arenosa at 9 and 15 DAP, respectively. (C and D) 4x A. lyrata at 9 and 15 DAP, respectively. (E and F) 4x A. lyrata × 2x A. arenosa at 9 and 15 DAP, respectively. (G and H) 2x A. arenosa × 4x A. lyrata at 9 and 15 DAP, respectively. (I and J) 4x A. arenosa × 2x A. lyrata at 9 and 15 DAP, respectively. (K and L) 2x A. lyrata × 4x A. arenosa at 9 and 15 DAP, respectively. (M and N) 4x A. arenosa × 4x A. lyrata at 9 and 15 DAP, respectively. (O and P) 4x A. lyrata × 4x A. arenosa at 9 and 15 DAP, respectively. The directionality of the cross is indicated seed parent (♀) × pollen donor (♂). An early (9 DAP) and late (15 DAP) developmental time point is displayed. Images shown in this figure are representative for a total number of observed seeds of at least 20 per biological replicate (three replicates). (Scale bar, 50 µm.) 2A: 2x A. arenosa; 2L: 2x A. lyrata; 4A: 4x A. arenosa; 4L: 4x A. lyrata.

Fig. 5.

Rescue of hybrid seeds involving tetraploid A. lyrata does not correlate with endosperm proliferation rate. (A) Endosperm proliferation was assessed by counting endosperm nuclei number at 5, 7, and 9 DAP. (B) Proliferation rate was calculated as the ratio of nuclei number at 5 and 7 DAP and at 7 and 9 DAP. Parental tetraploid species are represented by dark red (A. arenosa) and dark blue (A. lyrata) colors and reciprocal hybrids by shades: from darker to lighter red, 4x A. arenosa × 2x A. lyrata, 2x A. lyrata × 4x A. arenosa and 4x A. arenosa × 4x A. lyrata respectively; from darker to lighter blue, 4x A. lyrata × 2x A. arenosa, 2x A. arenosa × 4x A. lyrata, 4x A. lyrata × 4x A. arenosa. The cross (†) at 9 DAP indicates no or few endosperm nuclei detectable in 4x A. arenosa × 2x A. lyrata hybrid seeds. In A, error bars represent SD between three biological replicates (n = 5 seeds per sample). In B, the error bars were calculated as follow: ratio value × [(coefficient of variationtime22)+(coefficient of variationtime12)]/2. 2A: 2x A. arenosa; 2L: 2x A. lyrata; 4A: 4x A. arenosa; 4L: 4x A. lyrata.

Fig. S5.

Synthetic tetraploid A. lyrata restores hybrid seed viability similar as natural tetraploids. (A) Pictures of seeds obtained from controlled crosses between synthetic 4x A. lyrata and diploid A. arenosa. The directionality of the cross is indicated seed parent (♀) × pollen donor (♂). (Scale bars, 1 mm.) (B) Seed viability of interploidy interspecific crosses, as measured by the rate of noncollapsed and germinated seeds. (C) Seed size for indicated crosses. (D) Seed weight for indicated crosses. Error bars represent SD between cross replicates (>2 replicates for each sample). 2A: 2x A. arenosa; 4Lsynth: synthetic 4x A. lyrata.

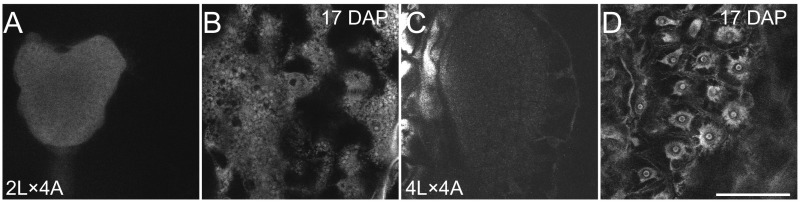

In contrast to 4x A. lyrata, 4x A. arenosa did not produce any viable hybrid seeds upon reciprocal crosses with 2x A. lyrata (Fig. 3B). Hybrid seeds derived from these crosses resembled the 2x A. lyrata × 2x A. arenosa reciprocal hybrid seeds, with an even more aggravated phenotype (Fig. 3). Thus, the average 4x A. arenosa × 2x A. lyrata seed area was extremely small, similar to 2x A. arenosa × 2x A. lyrata seeds, but with an even lower weight (Fig. 3 C and D). The endosperm of these seeds cellularized earlier than that of the parental seeds (9 DAP) (Fig. 4I). No significant proliferation could be observed between 5 and 7 DAP (Fig. 5), and the endosperm started to degenerate after 7 DAP (Fig. 4I and Fig. S4). In contrast, the nonviable 2x A. lyrata × 4x A. arenosa hybrid seeds remained uncellularized until 17 DAP, when the embryo had reached the late heart stage (Fig. 4 K–L and Fig. S6 A and B). In line with our previous observations, the proliferation rate of the endosperm was similar to that of parental lines (Fig. 2C and Fig. 5B).

Fig. S6.

Seventeen DAP endosperm cellularization phenotype (in 2L4A and 4L4A). Feulgen-stained seeds of A. lyrata, A. arenosa reciprocal hybrids at 17 DAP. (A and C) Embryo phenotype. (B and D) Endosperm cellularization phenotype. Images shown in this figure are representative for a total number of observed seeds of at least 20 per biological replicate. (Scale bar, 50 µm.) 4A: 4x A. arenosa; 4L: 4x A. lyrata 2L: 2x A. lyrata.

Tetraploid A. lyrata and A. arenosa populations are known to hybridize in the wild (15) and consistently, crosses between 4x A. lyrata and 4x A. arenosa gave viable seeds in both cross directions, with a phenotypic appearance that resembled the maternal parent (Fig. 3A). The seed area and seed weight were not significantly different from the midparent value (Fig. 3 C and D). Endosperm cellularization occurred at a similar time point in 4x A. arenosa × 4x A. lyrata compared with the tetraploid parents (Fig. 4 M and N). In the reciprocal cross, 4x A. lyrata × 4x A. arenosa hybrid embryo and endosperm were developmentally slightly delayed at 15 DAP (Fig. 4 and Fig. S4) but cellularization occurred at 17 DAP (Fig. S6 C and D). Despite this difference, the endosperm proliferation rates in the tetraploid reciprocal hybrid seeds were largely similar to that of the maternal species (Fig. 5B).

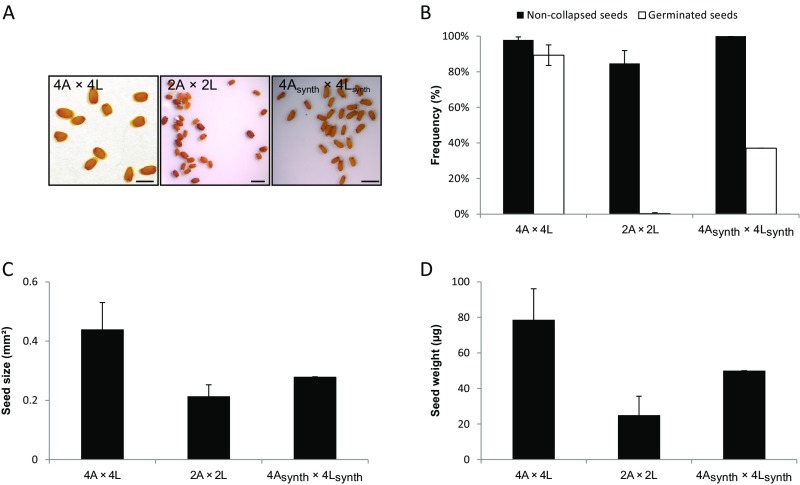

We considered the possibility that reproductive compatibility among these tetraploids is the consequence of repeated introgression between the two species, rather than a direct consequence of tetraploidization. To test this hypothesis, we generated synthetic 4x A. arenosa plants and hybridized them with synthetic 4x A. lyrata plants. Consistently, 4x A. arenosasynth × 4x A. lyratasynth seeds, although looking viable, germinated at a lower rate (<40%), and were drastically smaller both in seed size and weight, thus resembling the 2x A. arenosa × 2x A. lyrata hybrid seed phenotype (Fig. S7).

Fig. S7.

Hybrid seeds between synthetic tetraploid A. lyrata and A. arenosa resemble the hybrids between diploids, not between natural tetraploids. (A) Images of seeds obtained from controlled crosses between natural tetraploid, diploid and synthetic tetraploid A. arenosa and A. lyrata. The directionality of the cross is indicated seed parent (♀) × pollen donor (♂). (Scale bars, 1 mm.) (B) Seed viability of interspecific crosses, as measured by the rate of noncollapsed and germinated seeds. (C) Seed size for indicated crosses. (D) Seed weight for indicated crosses. Error bars represent SD between cross replicates (>2 replicates for each sample). 2A: 2x A. arenosa; 2L: 2x A. lyrata ; 4A: natural 4x A. arenosa; 4L: natural 4x A. lyrata; 4Asynth: synthetic 4x A. arenosa; 4Lsynth: synthetic 4x A. lyrata.

In conclusion, the sole tetraploidization of A. lyrata was sufficient to bypass the endosperm-based reproductive barrier between A. lyrata and A. arenosa. Therefore, we propose that a tetraploidization event in A. lyrata allowed the production of viable hybrid seeds, enabling gene flow between the two species.

The Hybridization Barrier Separating Diploid A. lyrata and A. arenosa Has a Multigenic Basis.

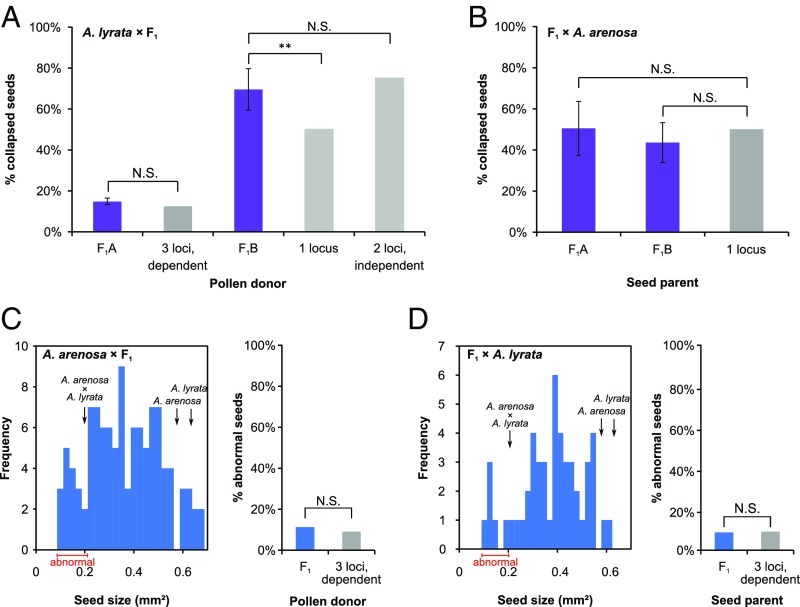

We inferred the genetic basis of the postzygotic incompatibility between A. lyrata and A. arenosa by observing the phenotypic segregation in diploid F1 backcrosses. Given the nonreciprocality of hybrid seed defects, we analyzed A. lyrata × A. arenosa F1 hybrids in both cross directions. Thus, we backcrossed F1 hybrids (♂) to A. lyrata (♀) to infer the number of paternal A. arenosa loci, and F1 hybrids (♀) × A. arenosa (♂) backcross allowed to assess the number of maternal A. lyrata loci underlying the A. lyrata (♀) × A. arenosa (♂) hybrid seed lethality (Fig. 6). To infer the genetic loci underlying incompatibility in the A. arenosa × A. lyrata cross, we analyzed F1 hybrids (♀) × A. lyrata (♂) and A. arenosa (♀) × F1 hybrids (♂).

Fig. 6.

A population-dependent, multilocus genetic basis underlies the A. lyrata × A. arenosa reciprocal hybridization barriers. (A and B) A. lyrata × A. arenosa F1 backcrosses to determine the genetic basis of A. lyrata × A. arenosa incompatibility. F1A and F1B correspond to two different A. lyrata × A. arenosa F1 hybrids generated using A. arenosa individuals from two different populations. Seed abortion rate is shown for A. lyrata × F1 (A) and F1 × A. arenosa (B) backcrosses. (C and D) F1 backcrosses to determine the genetic basis of A. arenosa × A. lyrata incompatibility. (Left) Seed size distribution of A. arenosa × F1 (C) and F1 × A. lyrata (D); (Right) expected and obtained rate of abnormal seeds. The range of abnormal seed size (lower than the 2A × 2L average seed size of 0.21 mm2) (Fig. 1) is indicated with red range bar. The average size of parental A. arenosa, A. lyrata, and A. arenosa × A. lyrata hybrid seeds is shown by black arrows. Experimental values are represented by purple and blue bars for A. lyrata × A. arenosa and A. arenosa × A. lyrata crosses, respectively. Gray bars represent theoretical values based on the number of indicated involved loci (38). Error bars represent SD between backcross replicates (4 backcrosses for each F1 type). **P < 0.01 (χ2 test) compared with the expected abortion rate for the number of indicated loci. N.S: nonsignificant.

We generated two different A. lyrata × A. arenosa F1 hybrids (F1A and F1B) using A. arenosa individuals from two different populations (Table S1) in backcrosses with parental plants. Strikingly, A. lyrata × F1 seed abortion rates varied from 15 to 69% depending on the F1 plant used, suggesting segregating alleles in the parental species (Fig. 6A). Backcrosses using F1A produced 15% (n = 101 seeds) aborted seeds, which is not significantly different (P = 0.17, χ2 test) from a theoretical expectation of 12.5% for a combination of three A. arenosa paternal loci required to induce seed abortion (38). However, F1B backcrosses resulted in 69% (n = 142 seeds) seed abortion, suggesting two independent A. arenosa paternal loci being involved with each of them sufficient to give hybrid seed abortion (expected seed abortion 75%, P = 0.15, χ2 test) (Fig. 6A). Because F1A and F1B hybrids were generated with A. arenosa individuals from two different populations, these data suggest that the genetic basis of the A. lyrata × A. arenosa incompatibility differs between A. arenosa populations, but nevertheless results in the same hybrid seed phenotype.

Table S1.

Origin of parents used to produce F1 hybrids

| Type | Seed parent | Pollen donor |

| F1A | A. lyrata pop. MJ09-11 | A. arenosa pop. MJ09-1 |

| F1B | A. lyrata pop. MJ09-11 | A. arenosa pop. MJ09-5 |

| Backcrossed A. lyrata | A. lyrata pop. MJ09-11 | A. lyrata pop. MJ09-11 |

| Backcrossed A. arenosa | A. arenosa pop. MJ09-1 | A. arenosa pop. MJ09-1 |

The table also indicates the origin of backcrossed parents.

Crossing the A. lyrata × A. arenosa F1 individuals as seed parent with A. arenosa produced similar seed abortion rate independently of the F1 origin [50% for F1A (n = 230 seeds) and 43% for F1B (n = 126 seeds), P = 0.26 for F1A and P = 0.31 for F1B, χ2 test] (Fig. 6B). These data suggest that one A. lyrata maternal locus is sufficient to induce seed abortion upon interacting with one or multiple A. arenosa loci.

Hybrid seeds derived from A. arenosa × A. lyrata crosses have a normal shape but are extremely small compared with parental seeds (Fig. 1C). Therefore, seed size was measured in the F1 backcrosses and the proportion of seeds mimicking the A. arenosa × A. lyrata phenotype (seed size < 0.21 mm2), thus considered as “abnormal,” was estimated (Fig. 6 C and D). In A. arenosa × F1 and F1 × A. lyrata, the rate of abnormal seeds reached 15.6% (n = 109 seeds) and 12% (n = 50 seeds), respectively. This was not significantly different from the theoretical expectation of 12.5% in both cases (P = 0.34 and P = 1 respectively, χ2 test), suggesting that interaction of three paternal and three maternal loci underlies genetic incompatibility of A. arenosa × A. lyrata.

In conclusion, our results suggest that the genetic basis of the A. lyrata × A. arenosa incompatibility is not fixed within A. arenosa and differs between A. arenosa populations. Depending on the A. arenosa population, this hybridization barrier is built by two to three A. arenosa paternal loci that interact with one A. lyrata maternal locus to produce hybrid seed lethality. In contrast, the A. arenosa × A. lyrata incompatibility involves three parental loci on each side of the cross. Together, our data show that the endosperm-based hybridization barrier between A. lyrata and A. arenosa is based on a complex multiple loci interaction.

Discussion

In this study we found that endosperm-based hybridization barriers and bypassing of such by natural polyploidization can explain the gene flow between A. lyrata and A. arenosa. Until now, endosperm-based hybridization barriers have not been considered to play a major role in plant speciation, but the present study strongly suggests otherwise. We furthermore show that polyploidization can break down hybridization barriers and not only establish them, as implied by the classic triploid block concept. Polyploidy-mediated restoration of hybrid seed viability has been used in plant breeding to obtain artificial hybrids. This study, however, suggests that this phenomenon exists in the wild as well, playing an important role in reenabling gene flow between species. Although this work focuses on the case study of two sister species, A. lyrata and A. arenosa, the growing interest of the scientific community for endosperm-based hybridization barriers suggests that similar findings will be discovered in other plant species over the next years.

Endosperm-Based Hybridization Barriers Play an Important Role in Controlling Interspecific Gene Flow in A. lyrata and A. arenosa.

Species divergence is a highly dynamic process, associated with the accumulation of multiple reproductive barriers over time (12). Consequently, untangling the life history that led to the current state of gene flow, geographical distributions, or ecological preferences between species is rather complex, especially in the case of species with several ploidy levels, such as A. lyrata and A. arenosa. Therefore, measuring gene flow and the strength of specific reproductive barriers is a first important step toward understanding the life history of species. In this study, we focused on the endosperm-based postzygotic barrier preventing the formation of viable hybrid seeds between A. lyrata and A. arenosa and compared these results with documented gene flow between these species.

Two previous studies found no evidence for gene flow between diploid A. lyrata and A. arenosa (15, 16), consistent with our data demonstrating low viability of hybrid seeds in both hybridization directions. Our data thus suggest that hybrid seed lethality has contributed to the long-lasting complete isolation between the two diploid species. Nevertheless, hybrid seed viability rates reported in another study involving controlled crosses between diploid A. lyrata and A. arenosa were substantially higher (41). This difference could be because of genetic variation between natural populations, consistent with our data showing that the genetic basis of A. lyrata × A. arenosa hybrid seed lethality differs among A. arenosa populations. The presence of distinct incompatibility loci in A. arenosa populations suggests a recent intraspecific diversification of those loci and therefore a fast evolving genetic basis of hybrid incompatibility, similar to that proposed for other species (38, 44, 45). Genomic imprinting, the epigenetic phenomenon by which genes are expressed in a parent-of-origin manner, has been causally linked to endosperm-based hybridization barriers and is disturbed in interspecific hybrid seeds (24, 46–48). Moreover, genomic imprinting has been shown to vary among populations of the same species (49, 50). Together with parent-of-origin defects observed in the hybrid seeds, these facts make genomic imprinting a promising candidate molecular mechanism to explain interspecific hybrid seed lethality.

Tetraploid A. arenosa and diploid A. lyrata do not exhibit any gene flow (16), even though their geographical distributions overlap (51, 52). The strong reproductive barrier identified in our study provides an explanation as to how the two species can coexist in sympatry, suggesting that this reproductive barrier is maintained as a reinforcement mechanism, as previously proposed (39, 53). Tetraploids of both species coexist and hybridize in the wild (15, 16) and bidirectional gene flow was observed between the two species (16). These observations are fully supported by our data showing that hybrid seeds between tetraploid A. lyrata and A. arenosa are viable in both cross directions. Contrasting these observations, another study reported that gene flow between tetraploids was mainly unidirectional from A. arenosa to A. lyrata (15), suggesting that additional reproductive barriers act in a nonreciprocal way. We did not find any apparent difference in fertilization success depending on the cross direction, and therefore hypothesize that either additional postzygotic barriers impair 4x A. arenosa × 4x A. lyrata hybrid fitness, or that 4x A. lyrata × 4x A. arenosa hybrids are favored. In support of the latter hypothesis, 4x A. lyrata × 4x A. arenosa seeds were bigger with later endosperm cellularization than the reciprocal hybrid seeds, which may promote early seedling growth similar as reported for viable paternal excess triploid seedlings in A. thaliana (54).

In conclusion, the strong association between documented gene flow and the viability of hybrid seeds suggests an important role for endosperm-based reproductive barriers in controlling gene flow between A. lyrata and A. arenosa.

Gene Flow Between A. lyrata and A. arenosa May Have Been Enabled by A. lyrata Tetraploidization.

Endosperm cellularization has been suggested to regulate resource accumulation by shifting the resource sink from the endosperm to the embryo, and is therefore crucial for the embryo feeding and survival (55, 56). Thus, impairing this developmental transition leads to embryo arrest and seed lethality (33, 34). In this study, we showed that the inviability of hybrid seeds between 2x A. lyrata and 2x A. arenosa is due to nonreciprocal endosperm cellularization defects. In 2x A. lyrata × 2x A. arenosa hybrid seeds, the endosperm fails to cellularize, whereas in the reciprocal cross direction the endosperm cellularizes precociously. Similar defects were observed in interploidy hybrid seeds originating from paternal and maternal genome excess, respectively (29–31). Abnormal endosperm development in 2x A. lyrata × 2x A. arenosa reciprocal hybrid seeds thus mimics a genome dosage imbalance, with A. arenosa behaving as a higher ploidy parent. According to the EBN hypothesis, this would imply that at the same ploidy level the A. arenosa genome contribution to the endosperm has a higher effective ploidy than the A. lyrata genome, or a higher EBN (40). In this scenario, we therefore assign an EBN of 1 to the diploid A. lyrata and 2 to the diploid A. arenosa. In reciprocal diploid interspecies crosses, this produces a deviation from the required 2:1 EBN ratio in the endosperm (4:1 and 2:2 maternal:paternal ratio), leading to hybrid seed inviability. The EBN hypothesis predicts that the effective ploidy in the endosperm increases with the ploidy of the species. Increasing the ploidy of a low EBN species matches its effective ploidy with a higher EBN species, and thus allows the production of viable hybrid seeds (21, 25). Aligned with our observations, an EBN expectation increased to 2 in both natural and synthetic tetraploid A. lyrata restores endosperm cellularization and produces viable seeds when crossed with the diploid A. arenosa (EBN = 2). Furthermore, reciprocal crosses with tetraploid A. arenosa (EBN = 4) and diploid A. lyrata (EBN = 1) increases the severity of hybrid defects compared with diploid hybrids, because the difference of EBN between the two species is even higher (8:1 and 1:2 maternal:paternal ratio).

In the tetraploid species, the same difference in EBN as between diploids is expected (EBN = 2 and 4 for tetraploid A. lyrata and A. arenosa, respectively). The phenotype of the hybrid seeds between the synthetic tetraploids is similar to the seed phenotype obtained from the diploid × diploid hybrids, suggesting that the synthetic tetraploid A. arenosa has indeed a higher EBN than the synthetic tetraploid A. lyrata. The molecular mechanism underlying the EBN remains to be discovered. To this end, deregulated imprinted genes underpin endosperm-based hybridization barriers (46–48), and are thus likely to form the molecular basis of the EBN. Consistent with this idea, Solanum species with different EBNs exhibit different genomic imprinting patterns (48). Additional studies are needed to determine whether this difference not only correlates with but is indeed causative for the EBN.

Altogether, we propose the following scenario: facilitated by the autotetraploidization of A. lyrata, previously reproductively isolated A. lyrata and A. arenosa became able to form viable hybrid seeds. The initial hybridization event(s) took place between autotetraploid A. lyrata and diploid A. arenosa. This conclusion is in agreement with the pattern of gene flow between A. lyrata and A. arenosa that only involves the tetraploid A. lyrata, whereas the diploid A. lyrata is still reproductively isolated from A. arenosa (15, 16). Following the initial hybridization, introgression of A. arenosa loci into A. lyrata allowed its compatibility with tetraploid A. arenosa, as supported by the viability of hybrid seeds between natural tetraploids, explaining the ongoing interspecific gene flow observed at the tetraploid level (15, 16). The bypass of hybridization barriers by polyploidization has been shown in artificial hybridization experiments (21, 25) but, to our knowledge, it has never been documented in wild populations. Polyploidization may thus play a prominent role in plant evolution, not only by mere reproductive isolation (57), but also by weakening hybridization barriers between related species.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material and Growth Conditions.

All accessions used in this study originate from wild populations located in Central Europe, previously described by Jørgensen et al. (16) (Fig. S1 and Table S2 for details). Diploid F1 hybrids were obtained from the 2x A. lyrata population MJ09-11 and 2x A. arenosa populations MJ09-1 and MJ09-5. For parental backcrosses of hybrids, A. lyrata MJ09-11 and A. arenosa MJ09-1 and MJ09-5 were used. Two to six F1 hybrid individuals per cross type were backcrossed to the respective parental species.

Table S2.

Sampling of A. arenosa and A. lyrata included in this study

| Collection no. | Taxon | Ploidal level | Locality | Latitude | Longitude | Jørgensen et al. (16) |

| MJ09-1 | A. arenosa | 2x | SVK: Vysoké Tatry; Prešovský kraj; Belianske Tatry; Zadné Med'odoly Valley; Kopské Sedlo | N 49.2569 | E 20.1431 | a2_SVK1 |

| MJ09-4 | A. arenosa | 2x | SVK: Nízke Tatry Mts.; Pusté Pole | N 48.8855 | E 20.2408 | a2_SVK2 |

| MJ09-5 | A. arenosa | 2x | SVK: Vel'ká Fatra Mts.; Harmanec; Malý Šturec Sedlo | N 48.8385 | E 18.9987 | a2_SVK3 |

| MJ09-8 | A. lyrata | 4x | AUT: Lower Austria; Dunkelstein Forest; Wachau; N Bacharnsdorf | N 48.4000 | E 15.5377 | l4_AUT3 |

| MJ09-9 | A. arenosa | 4x | AUT: Lower Austria; Eastern Alps; SSW St. Aegyd am Neuwalde; Kernhof | N 47.8178 | E 15.5350 | a4_AUT1 |

| MJ09-11 | A. lyrata | 2x | AUT: Lower Austria; street from Pernitz to Pottenstein | N 47.9190 | E 15.9755 | l2_AUT1 |

| MJ09-12 | A. lyrata | 2x | AUT: Lower Austria; S Vienna; Bad Vöslau; rocks near Vöslauer Hütte | N 47.9798 | E 16.1637 | l2_AUT2 |

Country names are abbreviated as follows: AUT, Austria; CZE, Czech Republic; GER, Germany; SVK, Slovakia. Collected by Marte H. Jørgensen July 23–28, 2009. Population number used in Jørgensen et al. (16) listed in the last column.

All seeds were surface-sterilized using 5% (vol/vol) sodium hypochloride solution under the fume hood. After sterilization, seeds were plated on Petri dishes with Murashige and Skoog medium [MS2 (58), containing 1% sucrose and solidified with 1% bactoagar]. After stratification for 3 wk in the dark at 4 °C, germinated seedlings were grown in a growth room under long-day photoperiod (16-h light and 8-h darkness) at 22 °C light and 20 °C darkness temperature and a light intensity of 100 µE. Seedlings at the four-to-six leaf stage were transferred to soil and plants were grown in plant growth chambers at 60% humidity and daily cycles of 16-h light at 18 or 21 °C and 8-h darkness at 18 °C. After 3 wk, rosette-stage plants were transferred to winter conditions (10-h light and 14-h darkness at 8 °C) for 8–10 wk.

Plant Crosses.

For all crosses, designated female partners were emasculated, and the pistils were hand-pollinated 2 to 3 d after emasculation. At least three biological replicates were made for each cross unless specified otherwise. Each biological replicate consisted of two or more siliques unless otherwise specified.

Scoring of Seed Phenotypes.

Seeds were arranged on white plastic dishes and imaged using a Nikon D90 camera and Leica Z16apoA microscope. Seed size was measured by converting images to black and white using the “threshold” and “Analyze Particles” functions in ImageJ (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). Seed weight of 30–150 seeds per replicate was determined with an Ohaus GA110 or Mettler AC100 scale and the total weight was divided by the number of seeds. Hybrid seeds that weighed less than the minimum range of the scale were given the value 0.0001 g per 50 seeds (smallest scorable weight). Noncollapsed seeds were scored from three replicates of imaged seed pools and characterized as brown and plump with variable size. Collapsed seeds were black or black and shriveled, brown and shriveled or not round, or very small seeds (less than 0.2 mm2).

Germination Assays.

One month after harvesting, seeds were surface-sterilized described and plated on MS2 media without sucrose. To break seed dormancy, plates were then kept at 4 °C for 6 wk and put to normal growth conditions (see above) for 1 mo. Germination rates were assessed by counting seeds with ruptured seed coat and protruding radicles.

In Vitro Embryo Rescue.

Hybrid embryos derived from seeds of crosses of A. lyrata × A. arenosa were rescued at 27 DAP by in vitro cultivation. After a short incubation of siliques in 70% (vol/vol) ethanol, the embryos were isolated by dissection using hypodermic needles and placed on MS media containing 2% (wt/vol) sucrose. Plates were incubated in a light chamber. Surviving seedlings were transferred to soil after 14 d.

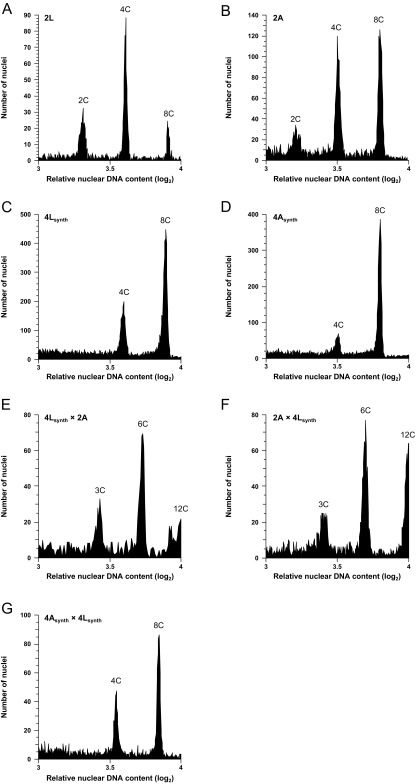

Generation of Synthetic 4x A. lyrata and 4x A. arenosa.

To obtain synthetic tetraploid plants from the diploid A. lyrata and A. arenosa, 10 µL of 0.25% colchicine solution was applied on the shoot apical meristem of 1-mo-old seedlings. Ploidy was determined by comparing the pollen size with diploids under the microscope. Then, leaves from each floral stem were harvested and their ploidy level was confirmed using a CyFlow ploidy analyzer (Sysmex-Partec). The stems revealed to be tetraploid were used for crosses. To rule out chimeric ploidy in these stems, the ploidy of five progenies obtained from each cross involving synthetic tetraploids was measured (Fig. S8). Only cross results where all of the surveyed progenies had the expected ploidy level (3× from 2x × 4x crosses, 4x from 4x × 4x crosses), were used for this study.

Fig. S8.

Ploidy level assessment of the synthetic 4x A. lyrata and 4x A. arenosa. Ploidy levels were estimated by measuring the relative nuclear DNA content of each sample by flow cytometry. The A. lyrata and A. arenosa diploid controls are shown in A and B. On top of nuclear DNA, content matching with diploid cells (2C), tetraploid (4C), and octoploid (8C) cells can be seen because of different mitotic stages and endoreduplication. The relative nuclear DNA content of colchicine treated positive stems (4x) is shown for A. lyrata (C) and A. arenosa (D). In these samples, as in diploids, an octoploid level (8C) is seen because of cells in G2 mitotic phases and endoreduplication, but tetraploidy (4C) is the lowest ploidy level observable. Progenies obtained from synthetic 4x A. lyrata × 2x A. arenosa (E) and 2x A. arenosa × synthetic 4x A. lyrata (F) are triploid as shown by the intermediate relative nuclear DNA content between diploids and tetraploids (3C, 6C, and 12C). Progenies obtained from synthetic 4x A. arenosa × synthetic 4x A. lyrata (G) are tetraploid, as their relative nuclear DNA content was similar to the tetraploid parents. For each biological sample, n = 5 replicates. The directionality of the cross is indicated seed parent (♀) × pollen donor (♂). 2A: 2x A. arenosa; 2L: 2x A. lyrata ; 4Asynth: synthetic 4x A. arenosa; 4Lsynth: synthetic 4x A. lyrata.

Microscopy.

Clearing analysis was performed as previously described (59, 60) and imaged using a Zeiss axioplan Imaging2 microscope system equipped with Nomarski optics and cooled LCD imaging facilities.

Endosperm nuclei counts were conducted on cleared seeds at defined time points. Seeds were fixed in 9:1 EtOH:Acetic acid. After 1-d incubation in chloral hydrate solution [1:8:3 glycerol/chloral hydrate/water (vol/vol)] at 4 °C, a stack of pictures were taken throughout the whole seed and endosperm nuclei were subsequently counted in each picture using ImageJ cell counter (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

A total of 20 seeds per biological replicate (three biological replicates) were sampled at 9 and 15 DAP for investigation of endosperm cellularization. Preparation of seeds was performed using Feulgen staining as described by Braselton et al. (61). Imaging of optical sections of the endosperm was performed using a multiphoton Zeiss LSN NLO microscope with an excitation wavelength of 770 nm and emission from 518 nm and onwards or an Olympus FluoView 1000 Confocal Laser Scanning microscope (BX61WI) with an excitation of 488 nm and emission from 500 to 600 nm.

Statistical Analysis.

Seed size and weight of hybrid seeds were compared with the midparent value (42) using Student’s t test. The endosperm proliferation rate was calculated as the ratio of nuclei number between two time points. Finally, χ2 test was used to test for differences from expected frequencies according to Mendelian segregation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Roswitha Schmickl for fruitful discussion. This research was supported by a Funding Scheme for Independent Projects (FRIPRO) Grant 214052/F20 from the Norwegian Research Council (to P.E.G.) and a European Research Council Starting Independent Researcher grant (to C.K.). C.L.-P. was supported by a grant from the Nilsson-Ehle Foundation. K.S.H and I.M.J. were supported by the Norwegian Ministry of Education and the Centre for Epigenetics, Development and Evolution.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1615123114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Mayr E. What is a species, and what is not? Philos Sci. 1996;63(2):262–277. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winge Ø. The chromosomes. Their numbers and general importance. Compt Rend Trav Lab Carlsberg. 1917;13:131–175. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Müntzing A. Outlines to a genetic monograph of the genus Galeopsis. Hereditas. 1930;13(2–3):185–341. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stebbins GL. The role of hybridization in evolution. Proc Am Philos Soc. 1959;103(2):231–251. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yakimowski SB, Rieseberg LH. The role of homoploid hybridization in evolution: A century of studies synthesizing genetics and ecology. Am J Bot. 2014;101(8):1247–1258. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1400201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Douglas GM, et al. Hybrid origins and the earliest stages of diploidization in the highly successful recent polyploid Capsella bursa-pastoris. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(9):2806–2811. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1412277112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vallejo-Marín M, Buggs RJA, Cooley AM, Puzey JR. Speciation by genome duplication: Repeated origins and genomic composition of the recently formed allopolyploid species Mimulus peregrinus. Evolution. 2015;69(6):1487–1500. doi: 10.1111/evo.12678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suarez-Gonzalez A, et al. Genomic and functional approaches reveal a case of adaptive introgression from Populus balsamifera (balsam poplar) in P. trichocarpa (black cottonwood) Mol Ecol. 2016;25(11):2427–2442. doi: 10.1111/mec.13539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Novikova PY, et al. Sequencing of the genus Arabidopsis identifies a complex history of nonbifurcating speciation and abundant trans-specific polymorphism. Nat Genet. 2016;48(9):1077–1082. doi: 10.1038/ng.3617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doolittle WF. Phylogenetic classification and the universal tree. Science. 1999;284(5423):2124–2129. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5423.2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Linder CR, Rieseberg LH. Reconstructing patterns of reticulate evolution in plants. Am J Bot. 2004;91(10):1700–1708. doi: 10.3732/ajb.91.10.1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seehausen O, et al. Genomics and the origin of species. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15(3):176–192. doi: 10.1038/nrg3644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jakobsson M, et al. A unique recent origin of the allotetraploid species Arabidopsis suecica: Evidence from nuclear DNA markers. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23(6):1217–1231. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msk006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shimizu-Inatsugi R, et al. The allopolyploid Arabidopsis kamchatica originated from multiple individuals of Arabidopsis lyrata and Arabidopsis halleri. Mol Ecol. 2009;18(19):4024–4048. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmickl R, Koch MA. Arabidopsis hybrid speciation processes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(34):14192–14197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104212108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jørgensen MH, Ehrich D, Schmickl R, Koch MA, Brysting AK. Interspecific and interploidal gene flow in Central European Arabidopsis (Brassicaceae) BMC Evol Biol. 2011;11:346. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-11-346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koch MA, Matschinger M. Evolution and genetic differentiation among relatives of Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(15):6272–6277. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701338104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arnold B, Kim S-T, Bomblies K. Single geographic origin of a widespread autotetraploid Arabidopsis arenosa lineage followed by interploidy admixture. Mol Biol Evol. 2015;32(6):1382–1395. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msv089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kolář F, et al. Northern glacial refugia and altitudinal niche divergence shape genome-wide differentiation in the emerging plant model Arabidopsis arenosa. Mol Ecol. 2016;25(16):3929–3949. doi: 10.1111/mec.13721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schatlowski N, Köhler C. Tearing down barriers: Understanding the molecular mechanisms of interploidy hybridizations. J Exp Bot. 2012;63(17):6059–6067. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnston SA, Hanneman RE., Jr Manipulations of endosperm balance number overcome crossing barriers between diploid solanum species. Science. 1982;217(4558):446–448. doi: 10.1126/science.217.4558.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arisumi T. Endosperm balance numbers among New Guinea-Indonesian Impatiens species. J Hered. 1982;73(3):240–242. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parrott WA, Smith RR. Evidence for the existence of endosperm balance number in the true clovers (Trifolium spp.) Can J Genet Cytol. 1986;28(4):581–586. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Josefsson C, Dilkes B, Comai L. Parent-dependent loss of gene silencing during interspecies hybridization. Curr Biol. 2006;16(13):1322–1328. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walia H, et al. Dosage-dependent deregulation of an AGAMOUS-LIKE gene cluster contributes to interspecific incompatibility. Curr Biol. 2009;19(13):1128–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.05.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bleckmann A, Alter S, Dresselhaus T. The beginning of a seed: Regulatory mechanisms of double fertilization. Front Plant Sci. 2014;5:452. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin B-Y. Ploidy barrier to endosperm development in maize. Genetics. 1984;107(1):103–115. doi: 10.1093/genetics/107.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leblanc O, Pointe C, Hernandez M. Cell cycle progression during endosperm development in Zea mays depends on parental dosage effects. Plant J. 2002;32(6):1057–1066. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scott RJ, Spielman M, Bailey J, Dickinson HG. Parent-of-origin effects on seed development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development. 1998;125(17):3329–3341. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.17.3329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pennington PD, Costa LM, Gutierrez-Marcos JF, Greenland AJ, Dickinson HG. When genomes collide: Aberrant seed development following maize interploidy crosses. Ann Bot (Lond) 2008;101(6):833–843. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcn017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sekine D, et al. Dissection of two major components of the post-zygotic hybridization barrier in rice endosperm. Plant J. 2013;76(5):792–799. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chaudhury AM, et al. Fertilization-independent seed development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(8):4223–4228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pignocchi C, et al. ENDOSPERM DEFECTIVE1 is a novel microtubule-associated protein essential for seed development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2009;21(1):90–105. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.061812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hehenberger E, Kradolfer D, Köhler C. Endosperm cellularization defines an important developmental transition for embryo development. Development. 2012;139(11):2031–2039. doi: 10.1242/dev.077057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brink RA, Cooper DC. The endosperm in seed development. Bot Rev. 1947;13(8):423–477. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Valentine DH, Woodell SRJ. Studies in British primulas. X. Seed incompatibility in intraspecific and interspecific crosses at diploid and tetraploid levels. New Phytol. 1963;62(2):125–143. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ishikawa R, et al. Rice interspecies hybrids show precocious or delayed developmental transitions in the endosperm without change to the rate of syncytial nuclear division. Plant J. 2011;65(5):798–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rebernig CA, Lafon-Placette C, Hatorangan MR, Slotte T, Köhler C. Non-reciprocal interspecies hybridization barriers in the Capsella genus are established in the endosperm. PLoS Genet. 2015;11(6):e1005295. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lafon-Placette C, Köhler C. Endosperm-based postzygotic hybridization barriers: Developmental mechanisms and evolutionary drivers. Mol Ecol. 2016;25(11):2620–2629. doi: 10.1111/mec.13552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnston SA, den Nijs TPM, Peloquin SJ, Hanneman RE., Jr The significance of genic balance to endosperm development in interspecific crosses. Theor Appl Genet. 1980;57(1):5–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00276002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muir G, et al. Exogenous selection rather than cytonuclear incompatibilities shapes asymmetrical fitness of reciprocal Arabidopsis hybrids. Ecol Evol. 2015;5(8):1734–1745. doi: 10.1002/ece3.1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hayman BI, Mather K. The description of genic interactions in continuous variation. Biometrics. 1955;11(1):69–82. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramsey J, Schemske DW. Pathways, mechanisms, and rates of polyploid formation in flowering plants. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 1998;29:467–501. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burkart-Waco D, et al. Hybrid incompatibility in Arabidopsis is determined by a multiple-locus genetic network. Plant Physiol. 2012;158(2):801–812. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.188706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garner AG, Kenney AM, Fishman L, Sweigart AL. Genetic loci with parent-of-origin effects cause hybrid seed lethality in crosses between Mimulus species. New Phytol. 2016;211(1):319–331. doi: 10.1111/nph.13897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kradolfer D, Wolff P, Jiang H, Siretskiy A, Köhler C. An imprinted gene underlies postzygotic reproductive isolation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Dev Cell. 2013;26(5):525–535. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wolff P, Jiang H, Wang G, Santos-González J, Köhler C. Paternally expressed imprinted genes establish postzygotic hybridization barriers in Arabidopsis thaliana. Elife. 2015;4:e10074. doi: 10.7554/eLife.10074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Florez-Rueda AM, et al. Genomic imprinting in the endosperm is systematically perturbed in abortive hybrid tomato seeds. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33(11):2935–2946. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pignatta D, et al. Natural epigenetic polymorphisms lead to intraspecific variation in Arabidopsis gene imprinting. Elife. 2014;3:e03198. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Klosinska M, Picard CL, Gehring M. Conserved imprinting associated with unique epigenetic signatures in the Arabidopsis genus. Nat Plants. 2016;2:16145. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2016.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schmickl R, Jørgensen MH, Brysting AK, Koch MA. The evolutionary history of the Arabidopsis lyrata complex: a hybrid in the amphi-Beringian area closes a large distribution gap and builds up a genetic barrier. BMC Evol Biol. 2010;10:98. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schmickl R, Paule J, Klein J, Marhold K, Koch MA. The evolutionary history of the Arabidopsis arenosa complex: Diverse tetraploids mask the Western Carpathian center of species and genetic diversity. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e42691. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Coyne JA, Orr HA. Speciation. Sinauer Associates; Sunderland, MA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fort A, et al. Disaggregating polyploidy, parental genome dosage and hybridity contributions to heterosis in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2016;209(2):590–599. doi: 10.1111/nph.13650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morley-Smith ER, et al. The transport of sugars to developing embryos is not via the bulk endosperm in oilseed rape seeds. Plant Physiol. 2008;147(4):2121–2130. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.124644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lafon-Placette C, Köhler C. Embryo and endosperm, partners in seed development. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2014;17:64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Köhler C, Mittelsten Scheid O, Erilova A. The impact of the triploid block on the origin and evolution of polyploid plants. Trends Genet. 2010;26(3):142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant. 1962;15(3):473–497. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grini PE, Jürgens G, Hülskamp M. Embryo and endosperm development is disrupted in the female gametophytic capulet mutants of Arabidopsis. Genetics. 2002;162(4):1911–1925. doi: 10.1093/genetics/162.4.1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roszak P, Köhler C. Polycomb group proteins are required to couple seed coat initiation to fertilization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(51):20826–20831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117111108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Braselton JP, Wilkinson MJ, Clulow SA. Feulgen staining of intact plant tissues for confocal microscopy. Biotech Histochem. 1996;71(2):84–87. doi: 10.3109/10520299609117139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]