Abstract

The literature has been contradictory regarding whether parents who were abused as children have a greater tendency to abuse their own children. A prospective 30-year follow-up study interviewed individuals with documented histories of childhood abuse and neglect and matched comparisons and a subset of their children. The study assessed maltreatment based on child protective service (CPS) agency records and reports by parents, nonparents, and offspring. The extent of the intergenerational transmission of abuse and neglect depended in large part on the source of the information used. Individuals with histories of childhood abuse and neglect have higher rates of being reported to CPS for child maltreatment but do not self-report more physical and sexual abuse than matched comparisons. Offspring of parents with histories of childhood abuse and neglect are more likely to report sexual abuse and neglect and that CPS was concerned about them at some point in their lives. The strongest evidence for the intergenerational transmission of maltreatment indicates that offspring are at risk for childhood neglect and sexual abuse, but detection or surveillance bias may account for the greater likelihood of CPS reports.

For years, the notion that abused children grow up to become abusive parents has been widely accepted in the field of child abuse and neglect (1–3). However, because many other factors in a person’s life (such as natural abilities, biological or genetic predispositions, or intervening relationships) may mediate the effects of child abuse and neglect, assessing the intergenerational transmission of abuse and neglect is challenging. Although some studies have provided empirical support for the intergenerational transmission of child abuse (4–10), other researchers have found no evidence for transmission (11–14). Critical reviews have called attention to serious methodological limitations of research examining this question (15–20). To date, studies are primarily cross-sectional snapshots, rather than prospective longitudinal studies in which children are followed up and assessed in adulthood. Studies that work backward from a population of abusive parents and inquire about their childhood histories may lead to an inflated rate of transmission because individuals who were abused but did not become abusive as a parent are not represented (8, 18, 20). Finally, theoretical explanations (21, 22) and empirical research have focused on the transmission of physical abuse, largely ignoring the role of childhood sexual abuse and neglect in the intergenerational transmission of child maltreatment.

The present study was designed to overcome many of the methodological limitations of previous work. We used a prospective cohorts design (23, 24), in which both groups were free of the “outcome” (i.e., intergenerational transmission) at the time they were selected for the study. We used court-substantiated cases and thus avoided ambiguity and potential biases associated with retrospective recall (19, 20). We included a comparison group matched as closely as possible for age, sex, race, and approximate social class because it is theoretically plausible that any relationship between child abuse or neglect and later outcomes is confounded or explained by social class differences. We ascertained outcomes using multiple sources of information (parent and nonparent self-reports, offspring report, and child protection agency records) and multiple measures from standardized instruments. Details of methods and materials are available as supplementary materials on Science Online. Although our primary focus was on the parent’s behavior toward their biological offspring, we also included an assessment of abuse of other children (nonoff-spring). We tested whether individuals who have documented histories of abuse or neglect in childhood continue the intergenerational transmission of child abuse toward their own offspring or someone else’s children. We also examined whether different types of child maltreatment (physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect) are passed on from one generation to the next.

The simplest model of intergenerational transmission is illustrated by the direct relationship across generations: G1→ G2 → G3. The G1 individuals (the first generation) are the parents of the G2 individuals (second generation), who have been participants in our longitudinal study and are now adults.G2 individuals represent those with documented histories of childhood abuse or neglect and those who represent the comparison group without documented histories of abuse or neglect. The offspring of the G2 individuals are the G3, or third generation.

The original sample was composed of 908 G2 children with documented cases of abuse and neglect during the years 1967 through 1971 in a Midwestern county area and a matched comparison group of children (N = 667) from the same neighborhoods. The study was begun as an archival records check with a search of criminal histories for both groups (25). The first in-person interviews were conducted from 1989 to 1995, when G2 participants were on average 29 years old (N = 1196). Since that time, three additional interviews have been conducted with these participants (see table S1 for a chronology of the study and the supplementary materials and methods for details of the design of the study and participants). For the purpose of assessing the intergenerational transmission of abuse and neglect, we conducted interviews in 2009 and 2010 with 649 of the original G2 participants (mean age 47.0) and a subset of G3 offspring (N = 697, mean age 22.8). During 2011 to 2013, child protective service (CPS) agency records in the original state were searched for the entire sample and their children, and information was extracted and coded (26). Details of attrition and selection bias are provided in the supplementary materials. Despite attrition (see table S2), multiple analyses indicated that child maltreatment status was not a significant factor in nonparticipation in the last wave of the study. There was no difference between the abuse/neglect group and the comparison group in the prevalence of having children (at the first interview, 72.4% of the comparison group and 72.6% of the abuse/neglect group reported having at least one child; P = 0.94).

Because there is no single gold standard to assess child maltreatment, we used multiple sources of information, multiple measures to assess different types of maltreatment, and multiple time points when information was collected. Table 1 shows the percentage of G2 individuals in the abuse/neglect and comparison groups who have CPS agency records for any child maltreatment and specific types of physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect. G2 adults with documented histories of childhood abuse or neglect are twice as likely to be reported to CPS because their child was maltreated compared with matched comparisons. Overall, about a fifth of G2 individuals (21.4%) with documented histories of childhood abuse or neglect were reported to CPS agencies compared with 11.7% of matched comparisons [adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 2.01; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.42 to 2.85; P < 0.001, controlling for G2 age, sex, and race, and childhood neighborhood advantage and disadvantage]. These rates vary by type of child maltreatment being perpetrated, with increased risk for sexual abuse (AOR = 2.31, 95% CI =1.24 to 4.30, P< 0.001) and neglect (AOR = 2.06; 95% CI = 1.42 to 3.01; P < 0.001) but not for physical abuse (AOR = 1.26, 95% CI = 0.75 to 2.12, not significant).

Table 1. Child protective service agency records by childhood history of abuse or neglect.

The percentages reported here are based on individuals known to have lived within the original state at some point in their lives (N = 1147; see the supplementary materials for more details). Numbers for the specific types of abuse and neglect add up to more than the total for the abuse/neglect group overall because there is a small percentage of the subjects (10%) who have more than one type of abuse or neglect.

| Type of abuse and/or neglect experienced in childhood by G2 participants | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison group (N = 497) |

Abuse/Neglect (N = 650) |

Physical abuse (N = 108) |

Sexual abuse (N = 104) |

Neglect (N = 511) |

|||||

| Child protective service report |

% | % | AOR (95% CI) |

% | AOR (95% CI) |

% | AOR (95% CI) |

% | AOR (95% CI) |

| Any maltreatment | 11.7 | 21.4 | 2.01 (1.42–2.85)*** |

18.5 | 2.03 (1.10–3.73)* |

26.0 | 3.43 (1.86–6.34)*** |

21.1 | 1.88 (1.30–2.70)*** |

| Physical abuse | 5.4 | 6.9 | 1.26 (0.75–2.12) |

5.6 | 1.11 (0.40–3.04) |

4.8 | 1.13 (0.39–3.23) |

7.4 | 1.30 (0.76–2.23) |

| Sexual abuse | 3.4 | 7.7 | 2.31 (1.24–4.30)** |

7.4 | 3.90 (1.39–10.92)** |

10.6 | 4.49 (1.64–12.26)*** |

7.8 | 2.20 (1.15–4.19)* |

| Neglect | 9.5 | 18.0 | 2.06 (1.42–3.01)*** |

13.9 | 1.89 (0.96–3.69) |

22.1 | 3.40 (1.75–6.58)*** |

17.8 | 1.96 (1.32–2.91)*** |

| Failure to provide | 3.6 | 9.4 | 2.53 (1.45–4.39)*** |

7.4 | 2.56 (0.99–6.59)* |

12.5 | 4.07 (1.63–10.16)*** |

8.8 | 2.25 (1.26–4.02)** |

| Lack of supervision | 8.2 | 14.2 | 1.76 (1.18–2.65)** |

9.3 | 1.37 (0.62–3.00) |

15.4 | 2.55 (1.20–5.44)* |

14.7 | 1.79 (1.17–2.73)** |

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01;

P < 0.001

The intergenerational transmission hypothesis predicts that experiencing physical abuse in childhood will lead to increased risk for physically abusing one’s own children. Table 1 also presents our results showing the extent to which the type of maltreatment experienced as a child by G2 predicts a differential likelihood of maltreating a child. G2 individuals with any childhood abuse and neglect were reported to CPS more often than comparisons for any maltreatment, sexual abuse, and neglect but not for physical abuse. In sum, these results indicate that G2 adults with histories of childhood abuse and neglect are at increased risk for being reported to CPS agencies for sexual abuse and neglect but not for physical abuse, compared with matched comparison group subjects.

In addition to any involvement with CPS, we examined the number of reports filed against a G2 individual and the chronicity of reports. Of those G2 with an official CPS report (N = 213), 50.2% (106) have one report, 22.3% (47) have two reports, 10.0% (21) have three reports, and 17.5% (37) have four or more reports. There were no differences between G2 individuals with histories of abuse and/or neglect and comparison group members in the chronicity or mean number of reports (abuse/neglect M= 2.64, SD = 2.96; comparison M = 2.37, SD = 2.35).

Because official agency records represent only a portion of child maltreatment that occurs—that is, only that which comes to the attention of the authorities—researchers depend heavily on self-reports by parents or other caregiving adults for information about whether they have abused or neglected their children or someone else’s children. The top of Table 2 shows our results based on G2 parents’ self-reports of perpetrating physical and sexual abuse and neglect. In contrast to the results in Table 1, Table 2 shows that G2 individuals with documented histories were not more likely to report that they had physically or sexually abused their children. G2 parents with histories of childhood abuse/neglect (and those with histories of neglect) reported that they had engaged in behaviors that are considered neglectful more often than comparison parents. This increased risk for neglect (based on one of the two measures used) was found for the maltreated group overall (41.7% versus 29.0%, respectively; AOR = 1.83, P < 0.001) and those with histories of neglect (42.7%versus 29.0%, AOR = 1.92, P < 0.001). The bottom part of Table 2 shows that there were no significant differences in the extent of physical and sexual abuse reported by G2 nonparents (abuse/neglect versus comparisons).

Table 2. G2 parent and nonparent self-reports of perpetration of child abuse and neglect.

The reference group is the Comparison group. CTS, Conflict Tactics Scale, severe/very severe violence; CEQ, Childhood Experiences Questionnaire; NA, not applicable. For reports of physical abuse, the unadjusted ORs are 1.14, 1.00, 1.33, and 1.14 for nonparent G2s with histories of abuse/neglect overall, physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect, respectively. Due to the effects of control variables and small sample sizes here, the AORs appear inconsistent with raw percentages for G2 nonparents’ reports of physical abuse.

| Comparison group |

Abuse/Neglect | Physical abuse |

Sexual abuse |

Neglect | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G2 parent self-reports | |||||||||

| N | 257 | 304 | 42 | 49 | 244 | ||||

| Type of abuse or neglect reported |

% | % | AOR (95% CI) |

% | AOR (95% CI) |

% | AOR (95% CI) |

% | AOR (95% CI) |

| Physical abuse (CTS) |

23.9 | 26.4 | 1.01 (0.67–1.54) |

31.7 | 1.49 (0.67–3.29) |

31.3 | 1.14 (0.55–2.37) |

24.9 | 0.95 (0.61–1.48) |

| Sexual abuse | 1.9 | 3.3 | 1.69 (0.56–5.08) |

2.4 | 1.48 (0.15–14.63) |

0.0 | NA | 3.7 | 1.75 (0.57–58.40) |

| Neglect (CTS) | 51.4 | 53.2 | 1.02 (0.72–1.45) |

53.7 | 1.08 (0.53–2.17) |

47.9 | 0.83 (0.42–1.64) |

54.3 | 1.05 (0.72–1.52) |

| Neglect (CEQ) | 29.0 | 41.7 | 1.83 (1.25–2.67)*** |

39.0 | 1.52 (0.73–3.20 |

34.0 | 1.65 (0.79–3.42) |

42.7 | 1.92 (1.29–2.86)*** |

| G2 nonparent self-reports | |||||||||

| N | 34 | 54 | 12 | 5 | 42 | ||||

| Type of abuse or neglect reported |

% | % | AOR (95% CI) |

% | AOR (95% CI) |

% | AOR (95% CI) |

% | AOR (95% CI) |

| Physical abuse | 26.5 | 31.5 | 1.03 (0.37–2.87) |

25.0 | 1.68 (0.29–9.69) |

40.0 | 0.85 (0.04–18.68) |

31.0 | 0.86 (0.28–2.63) |

| Sexual abuse | 2.9 | 1.9 | 0.42 (0.01–21.27) |

0.0 | NA | 0.0 | NA | 2.4 | NA |

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01;

P < 0.001

During earlier waves of the study, we asked G2 participants whether they had experienced a variety of stressful life events during the past year. This information was collected during interviews when the G2 abused/neglected individuals and matched comparisons were mean age 29.2 (1989 to 1995), mean age 40.5 (2003 to 2005), and mean age 47.1 (2009 to 2010). Table 3 shows that at approximate age 29, almost 5% of G2 individuals with documented histories of childhood abuse and/or neglect (AOR = 3.85, 95% CI = 1.44 to 10.29, P < 0.01) and 5.7% of G2 with histories of neglect (AOR = 4.53, 95% CI = 1.68 to 12.21, P < 0.001) reported having had a child placed in the custody of the courts during the past year, compared with 1.6% of the comparisons

Table 3. G2 previous self-reports of trouble in relation to parenting.

Excludes parents who did not report having children.

| Comparison group |

Abuse/Neglect | Physical abuse | Sexual abuse | Neglect | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | AOR (95% CI) |

% | AOR (95% CI) |

% | AOR (95% CI) |

% | AOR (95% CI) |

|

| Mean age 29.2 | |||||||||

| During past year, child was placed in custody of courts |

1.6 | 4.7 | 3.85 (1.44–10.29)** |

2.6 | 2.76 (0.48–15.83) |

2.6 | 3.03 (0.48–19.13) |

5.7 | 4.53 (1.68–12.21)*** |

| N | 373 | 487 | 78 | 77 | 384 | ||||

| Mean age 40.5 | |||||||||

| During past year, child was placed in custody of courts |

1.3 | 4.8 | 3.77 (1.25–1.35)* |

1.6 | 1.19 (0.12–11.80) |

3.8 | 3.02 (0.46–19.64) |

5.6 | 4.29 (1.46–13.46)** |

| N | 298 | 377 | 61 | 52 | 304 | ||||

| Mean age 47.1 | |||||||||

| During past year, child was placed in custody of courts |

1.2 | 2.5 | 3.73 (0.76–18.33) |

2.6 | NA | 0 | NA | 2.6 | 3.62 (0.73–18.02) |

| N | 243 | 282 | 38 | 45 | 228 | ||||

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01;

P < 0.001

Approximately 12 years later, G2 adults with histories of abuse/neglect overall and neglect specifically were again more likely to report having a child placed in custody of the courts within the past year (4.8%, AOR = 3.77, 95% CI = 1.25 to 1.35, P < 0.05, and 5.6%, AOR = 4.29, 95% CI = 1.46 to 13.46, P < 0.01, respectively), compared with 1.3% of the controls. In the last interview (mean age 47), the G2 groups did not differ significantly, although twice as many G2 individuals with histories of abuse/neglect and neglect in particular reported having a child placed in the custody of the courts.

Thus far, the information presented has focused on the G2 parent generation. Because one might be skeptical of abusive parents’ willingness to report on their own behavior, it was important to have an additional assessment based on reports by G3 offspring of these individuals, along with official CPS reports. We used multiple self-report measures of physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect (see the supplementary materials for more detail) to ascertain whether the G3 offspring of individuals with documented histories of childhood abuse and neglect compared to offspring of nonmaltreated comparisons reported having been abused or neglected (see Table 4). G3 offspring of G2 parents with any history of abuse and/or neglect and neglect were significantly more likely to report having been sexually abused on one of three measures, compared with reports by G3 offspring of parents without such histories. G3 offspring of G2 parents with histories of abuse/neglect overall and histories of physical and sexual abuse reported higher rates of being neglected than controls.

Table 4. G3 offspring reports of experiencing child abuse and neglect.

Comparisons are to the controls. LONGSCAN, LS; LS 0–11 refers to the time period from ages 0 to 11; LS 12–17 refers to ages 12 to 17; AH, Adolescent Health; LTVH, Lifetime Trauma and Victimization History; CTS, Conflict Tactics Scale; CEQ, Childhood Experiences Questionnaire.

| G2 parent histories | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison group (N = 209) |

Abuse/Neglect (N = 245) |

Physical abuse (N = 35) |

Sexual abuse (N = 37) |

Neglect (N = 197) |

|||||

| G3 offspring report of abuse or neglect |

% | % | AOR (95% CI) |

% | AOR (95% CI) |

% | AOR (95% CI) |

% | AOR (95% CI) |

| Physical abuse (LS 0–11) |

74.6 | 67.4 | 0.75 (0.49–1.16) |

62.9 | 0.88 (0.38–2.01) |

64.9 | 0.73 (0.31–1.71) |

68.0 | 0.75 (0.47–1.18) |

| Physical abuse (LS 12–17) |

49.8 | 54.5 | 1.29 (0.87–1.92) |

51.4 | 1.37 (0.62–3.02) |

45.9 | 1.13 (0.51–2.53) |

55.2 | 1.34 (0.88–2.04) |

| Physical abuse (AH) |

20.7 | 26.9 | 1.48 (0.93–2.36) |

25.7 | 1.64 (0.68–3.95) |

18.9 | 1.01 (0.39–2.63) |

27.8 | 1.55 (0.95–2.52) |

| Physical abuse (LTVH) |

22.9 | 27.1 | 1.25 (0.80–1.97) |

32.4 | 1.65 (0.72–3.76) |

27.0 | 1.16 (0.50–2.72) |

26.0 | 1.23 (0.76–1.98) |

| Sexual abuse (LS 0–11) |

15.8 | 24.1 | 1.46 (0.89–2.38) |

25.7 | 2.03 (0.83–4.95) |

24.3 | 1.54 (0.60–3.91) |

24.4 | 1.40 (0.83–2.36) |

| Sexual abuse (LS 12–17) |

12.9 | 16.3 | 1.06 (0.61–1.84) |

17.1 | 1.76 (0.63–4.90) |

10.8 | 0.50 (0.14–1.82) |

17.3 | 1.09 (0.61–1.94) |

| Sexual abuse (AH) |

4.0 | 13.0 | 3.03 (1.34–6.87)** |

11.4 | 3.75 (0.92–15.34) |

5.7 | 1.70 (0.29–9.92) |

13.6 | 3.11 (1.34–7.21)** |

| Sexual abuse (LTVH) |

14.7 | 22.9 | 1.55 (0.92–2.60) |

23.3 | 1.82 (0.69–4.83) |

22.2 | 1.45 (0.54–3.87) |

23.1 | 1.51 (0.88–2.60) |

| Neglect (CTS) | 59.0 | 69.0 | 1.58 (1.03–2.40)* |

76.5 | 2.65 (1.10–6.39)* |

75.7 | 3.07 (1.15–8.17)* |

67.4 | 1.44 (0.92–2.26) |

| Neglect (AH) | 59.8 | 65.0 | 1.42 (0.95–2.13) |

62.9 | 1.55 (0.69–3.47) |

70.3 | 1.81 (0.77–4.25) |

64.6 | 1.38 (0.90–2.11) |

| Neglect (CEQ) | 40.1 | 48.1 | 1.51 (1.0–2.30)* |

34.4 | 0.77 (0.33–1.80) |

47.2 | 1.51 (0.69–3.31) |

47.6 | 1.49 (0.96–2.33) |

| Was CPS ever concerned? |

7.4 | 16.7 | 2.51 (1.31–4.83)** |

20.6 | 3.83 (1.32–11.16)** |

18.9 | 4.76 (1.48–15.34)** |

15.7 | 2.27 (1.14–4.52)* |

| Any of the above | 90.0 | 90.2 | 1.13 (0.59–2.15) |

91.4 | 1.54 (0.42–5.75) |

89.2 | 1.12 (0.29–4.34) |

90.9 | 1.23 (0.61–2.45) |

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01

P < 0.001

The bottom of Table 4 shows that more than twice as many of the G3 offspring of previously maltreated G2 individuals answered affirmatively to a question about whether “CPS was ever concerned about you” (16.7%of the G3 offspring ofG2 abused/neglected individuals compared with 7.4% of the comparison group offspring, AOR = 2.51, 95% CI = 1.31 to 4.83, P < 0.01). G3 offspring of G2 parents with all three types of maltreatment were also more likely to report that CPS was concerned about them (G3 offspring of G2 parents with histories of physical abuse = 20.6%, sexual abuse = 18.9%, and neglect = 15.7% compared with 7.4% of the comparison group offspring).

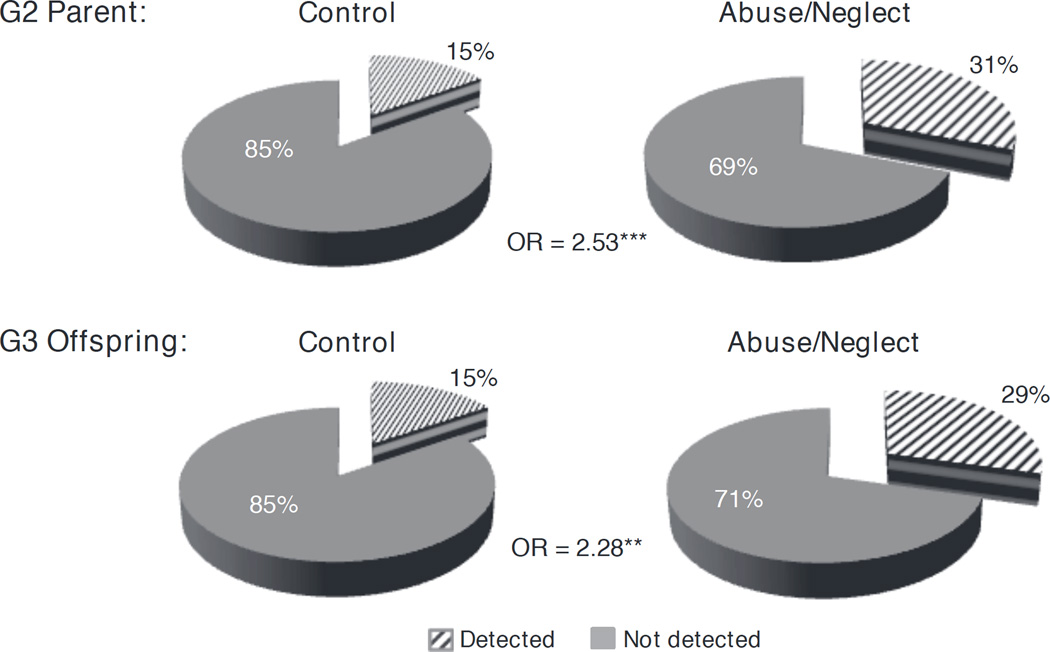

Finally, because of concerns about a possible detection or surveillance bias that may occur with increased surveillance of families involved with CPS, we also examined the extent to which participants (G2 and G3) who self-report child maltreatment have a CPS report. Presumably, because these individuals have reported that they either engaged in child maltreatment (G2 parents) or were the victim of child maltreatment (G3 offspring), we should expect approximately equal rates of official CPS reports, even though the concordance between self-reports and CPS reports is expected to be low (27, 28). Figure 1 shows that the detection rates for maltreatment are not equivalent across the groups. G2 parents with documented histories of childhood abuse and neglect are two and a half times more likely to have a CPS report than comparison parents (30.9% versus 15.0%, AOR = 2.53, 95% CI = 1.53 to 4.13, P = 0.000), suggesting a detection or surveillance bias. Similarly, among the G3 offspring who reported being abused or neglected, 29.3% of those whose parents had documented histories of childhood abuse or neglect were detected (that is, had an official CPS report), compared with 15.4% of the comparison group (whose parents did not have documented histories of childhood abuse or neglect), with an AOR = 2.28, 95% CI = 1.32 to 3.79, P < 0.003.

Fig. 1.

Rates of child protective system detection among G2 parents who report engaging in, and G3 offspring who report being the victim of, child abuse and/or neglect.

These findings suggest that our understanding of the intergenerational transmission of child abuse and neglect is more complex and challenging than expected. G2 parents with histories of childhood abuse or neglect are more likely to have G3 children who are reported to CPS agencies. Parents with histories of childhood abuse and neglect are more likely to report neglect of their offspring, but not physical or sexual abuse, compared to parents without documented histories of abuse and neglect. Offspring of parents with histories of childhood abuse and neglect are more likely to report being sexually abused and neglected. However, differences in these results make clear that the substance and extent of the intergenerational transmission of abuse and neglect depend in large part on the source of the information used to assess maltreatment. Having only one source of information may lead to incorrect conclusions.

The strongest evidence for the intergenerational transmission of maltreatment indicates that offspring are at risk for neglect and sexual abuse. Contrary to most theories, we found little evidence of the intergenerational transmission of physical abuse. Our findings were consistent across sources (G2 parent self-reports, G3 offspring reports, and CPS reports) that individuals with histories of child maltreatment were not at increased risk to physically abuse their children. Some have speculated that public education efforts to call attention to physical abuse and corporal punishment have had an effect on society and attitudes toward abuse (29) or, at a minimum, that these efforts have had an effect on willingness to report physical abuse. There is also trend data showing decreases in rates of physical abuse in national statistics (30). On the other hand, given that we found an increased risk for sexual abuse and neglect, it is not immediately apparent why these types of child maltreatment would not be subject to the same societal changes or attitudes.

Although there are numerous strengths associated with this research, several caveats need to be kept in mind. G2 abuse and neglect cases in this study were identified through official records from 40 years ago and represent children whose cases were processed through the courts. Many cases are not reported and never come to the attention of the authorities. Also, the abuse/neglect cases and comparisons in this study are predominantly from lower socioeconomic strata, and the association between poverty and child maltreatment (31) may in part explain the high rates of maltreatment in the sample in general. Thus, these findings may not be generalizable to unreported cases of abuse and neglect and to children from middle- or upper-class families who were abused or neglected. However, these results suggest the need for expanded prevention services and parent support within low-income communities. These findings are also not generalizable to abused and neglected children who were adopted in infancy or early childhood, because these cases were excluded from the sample. It is also possible that these findings represent an underestimate of the extent of child abuse and neglect perpetration, given that we may have missed older or sealed cases or cases that were lost over time. Finally, we are not able to report on the extent to which genetic factors may contribute to the intergenerational transmission of child abuse and neglect.

It is not easy to determine causality for any human behavior, especially in the natural environment, where, in contrast to the laboratory, comparisons are not easy to achieve. However, results based on this study’s cohort design lead us to conclude that further research is needed to understand the mechanisms underlying the intergenerational transmission of neglect and sexual abuse. These findings also have implications for child protective service systems that may be disproportionately scrutinizing families with past histories of child maltreatment, while overlooking instances of child abuse and neglect among families in the broader public. Research is needed to understand whether these families present more opportunities for intervention (e.g., are using more services) or whether they are truly more dysfunctional.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD40774), the National Institute of Justice (86-IJ-CX-0033 and 89-IJ-CX-0007), the National Institute of Mental Health (MH49467 and MH58386), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA17842 and DA10060), the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (AA09238 and AA11108), and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

www.sciencemag.org/content/347/6229/1480/suppl/DC1

Materials and Methods

Tables S1 to S4

References (32–52)

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Garbarino J, Gilliam JG. Understanding Abusive Families. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kempe RS, Kempe CH. Child Abuse. London: Fontana; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steele BF, Pollock CB. In: The Battered Child Syndrome. Helfer R, Kempe C, editors. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press; 1968. pp. 103–145. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berlin LJ, Appleyard K, Dodge KA. Child Dev. 2011;82:162–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01547.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dixon L, Browne K, Hamilton-Giachritsis C. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2005;46:47–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Egeland B, Jacobvitz D, Papatola K. In: Child Abuse and Neglect: Biosocial Dimensions. Gelles RJ, Lancaster JB, editors. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers; 1987. pp. 255–276. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunter RS, Kilstrom N. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1979;136:1320–1322. doi: 10.1176/ajp.136.10.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pears KC, Capaldi DM. Child Abuse Negl. 2001;25:1439–1461. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00286-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson R. J. Trauma Pract. 2006;5:57–72. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thornberry TP. Criminology. 2009;47:297–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2009.00153.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Altemeier WA, O’Connor S, Sherrod KB, Tucker D, Vietze P. Child Abuse Negl. 1986;10:319–330. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(86)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Renner LM, Slack KS. Child Abuse Negl. 2006;30:599–617. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sidebotham P, Golding J ALSPAC Study Team. Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Child Abuse Negl. 2001;25:1177–1200. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00261-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Widom CS. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry. 1989;59:355–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1989.tb01671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ertem IO, Leventhal JM, Dobbs S. Lancet. 2000;356:814–819. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02656-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herzberger SD. Am. Behav. Sci. 1990;33:529–545. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Falshaw L, Browne KD, Hollin CR. Aggress. Violent. Behav. 1996;1:389–404. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaufman J, Zigler E. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry. 1987;57:186–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1987.tb03528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thornberry TP, Knight KE, Lovegrove PJ. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2012;13:135–152. doi: 10.1177/1524838012447697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Widom CS. Psychol. Bull. 1989;106:3–28. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.106.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bandura A. Aggression: A Social Learning Analysis. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Science. 1990;250:1678–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.2270481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leventhal JM. Child Abuse Negl. 1982;6:113–123. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(82)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schulsinger F, Mednick SA, Knop J. Longitudinal Research: Methods and Uses in Behavioral Sciences. Boston: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Widom CS. Science. 1989;244:160–166. doi: 10.1126/science.2704995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.CPS is the unit within a government agency that responds to reports of child abuse or neglect. It typically falls within a state’s division of social services or department of children and family services. CPS units were first established in 1974 in response to the Federal Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA: Public Law 93–247) that provided funding for federal and state child maltreatment research and services. CAPTA mandated all states to establish procedures to investigate suspected incidents of child maltreatment in order to prevent, identify, and treat child abuse and neglect. A report must be made when an individual knows or has reasonable cause to believe or suspect that a child has been subjected to abuse or neglect.

- 27.Brown J, Cohen P, Johnson JG, Salzinger S. Child Abuse Negl. 1998;22:1065–1078. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(98)00087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Everson MD, et al. Child Maltreat. 2008;13:14–26. doi: 10.1177/1077559507307837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Straus MA, Gelles RJ. J. Marriage Fam. 1986;48:465–479. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finkelhor D, Jones LM. Have sexual abuse and physical abuse declined since the 1990s? University of New Hampshire, Crimes Against Children Research Center; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sedlak AJ, et al. Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS–4): Report to Congress, Executive Summary. Washington, DC: Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.