Abstract

BACKGROUND

In this clinical trial, polyethylene glycol (PEG) solution was compared with lactulose in the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis.

METHODS

This randomized controlled trial was performed on 40 patients in two groups. The patients in the lactulose group received either 20-30 grams of lactulose orally or by a nasogastric tube, or 200 grams of lactulose enema by a rectal tube. The patients in the PEG–lactulose group received the same amount of oral or rectal lactulose, plus 280 grams of PEG in 4 liters of water orally as a single dose in 30-120 minutes. Serial physical examinations, hepatic encephalopathy scoring algorithm (HESA), blood level of ammonia, and serum biochemical studies were used to evaluate the severity of hepatic encephalopathy.

RESULTS

In comparison with lactulose alone, PEG-lactulose could improve HESA score in 24 hours more effectively (p =0.04). Overall, PEG-lactulose regimen was associated with a decrease in length of hospital stay compared with lactulose treatment (p =0.03) but in subgroup analysis we found that PEG-lactulose regimen could only decrease the length of hospital stay in women significantly (p =0.01).

CONCLUSION

The use of PEG along with lactulose in comparison with lactulose alone is more effective in the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis and results in more rapid discharge from hospital.

Keywords: Hepatic Encephalopathy, Lactulose, Polyethylene Glycols, Liver Cirrhosis, Laxatives

INTRODUCTION

Cirrhosis is one of the leading causes of death in the United States and results in a significant economic burden ranges from $14 million to $2 billion due to its underlying etiology.1,2 According to the global burden of disease (GBD) study in 2013, cirrhosis is the 6th cause of death in developed countries and among the 10 most common causes of death in different world areas.3 This burden is expected to rise in the forthcoming years due to the increasing prevalence of cirrhotic cases related to HCV infection and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).4,5 Different studies show that most of patients with cirrhosis ultimately develop some degrees of hepatic encephalopathy and this condition is highly associated with increased mortality and health care costs.6 Hepatic encephalopathy, is further classified to overt hepatic encephalopathy (OHE) and minimal hepatic encephalopathy (MHE).7 It is estimated that 30-45% and 60-80% of patients with cirrhosis finally show OHE and MHE, respectively.6,8-10

There is a dearth of evidence backed by large, well controlled clinical trials in favor of specific treatment options currently in use for patients with MHE.11 However the existing evidence suggests some benefit of lactulose in the treatment of MHE.12,13

Treatment of patients with OHE is mainly based on the eliminating of underlying precipitating factors, nutritional supports, and reduction of blood ammonia level.11,14 Lactulose and rifaximin are the most widely used medications to reduce ammonia production; however their exact mechanism of action is still unclear.11

Rifaximin is a non-absorbable antibiotic that has been used for patients with OHE. It acts against coliforms like Escherichia coli, reduces the amount of serum ammonia and improves hepatic encephalopathy.15 A meta-analysis of 19 randomized controlled trials showed that rifaximin had beneficial effects on patients with OHE and may also reduce mortality in this population.16 However its cost remains a concern. A decision-analysis study found that rifaximin was not cost-effective as monotherapy in the treatment of patients with hepatic encephalopathy.17

Approximately 70% of patients with OHE improve on lactulose treatment.18 When used for secondary prophylaxis, lactulose reduces recurrent episodes of hepatic encephalopathy, but does not affect mortality.19 Lactulose is currently considered as the first line treatment of patients with OHE although there is no high-quality evidence to support it.20 In a Cochrane review, no significant differences in outcome was seen between the patients treated with or without lactulose.21 As a patient with OHE is admitted to hospital, predisposing factors often resolve along with the improvement in mental status; thus understanding the exact role of lactulose in this improvement is somehow difficult.22

Polyethylene glycol (PEG) is being studied for the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis and limited research has shown positive effects.23 In this clinical trial, PEG solution plus lactulose is compared with lactulose in the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This randomized controlled trial (RCT) was reviewed and approved by Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS) and the review board of Digestive Disease Research Institute (DDRI; approval letter number 416/984). All the studied patients provided an informed consent signed by themselves or their legally authorized representatives (LARs). LARs and the patients were free to quit this study anytime.

This RCT was performed in Shariati Hospital, a referral center for gastroenterological and liver diseases, Tehran province, Iran, from September 2015 to January 2016.

According to previous trials that had studied the effect of PEG and lactulose in the treatment of patients with cirrhosis and hepatic encephalopathy, we estimated the 24-hour improvement in hepatic encephalopathy scoring algorithm (HESA) score (see the next part) for PEG-lactulose group about 80% and for lactulose group about 50%.23-26 In addition, we assumed 2-sided first type error and second type error as 0.05 and 0.20, respectively and a drop-out rate of about 15%. Thus it is estimated that in order to have a statistically significant difference between two treatment groups, we need 24 patients in each group.

All patients with a known history of cirrhosis who presented with episodic hepatic encephalopathy were eligible to participate. Hepatic encephalopathy was defined as the onset of disorientation or asterixis according to The International Society for Hepatic Encephalopathy and Nitrogen Metabolism consensus and was assessed using HESA score.8

Patients having all the following criteria were included:

- Documented cirrhosis with any underlying etiology

- Hepatic encephalopathy of any grade

- 18 to 80 years of age

Exclusion criteria were as follows:

- Acute liver failure defined as severe acute liver injury with encephalopathy and international normalized ratio (INR)≥1.5 in a patient without pre-existing liver disease

- Acute change in mental status due to a diagnosis other than hepatic encephalopathy

- Hemodynamic instability obviating vasopressors for resuscitation

- Pregnancy

- Lack of LAR

- Refusal of consent by the LAR

- Patient’s unwillingness to participate

The patients were randomly assigned to two groups according to a series of block randomization numbers (8 blocks of 6 patients). The patients in the lactulose group received either 20-30 grams of lactulose (at least 3 doses in 24 hours) orally or by a nasogastric tube, or 200 grams of lactulose enema by a rectal tube. The patients in the PEG–lactulose group received the same amount of oral or rectal lactulose, plus 280 grams of PEG in 4 liters of water orally as a single dose during 30-120 minutes. Lactulose dose increased until at least two soft or loose bowel movements per day were produced. All the patients received otherwise routine care by the treating physician.

Serial physical examinations were performed at presentation and 24 hours later. We used HESA score to evaluate the severity of hepatic encephalopathy. This scoring system is an objective instrument and is more widely adopted than West Haven criteria.27 In order to avoid interpersonal variations, HESA scores at baseline and 24 hours afterwards were calculated by the same investigator.

Blood level of ammonia and serum biochemical studies were checked in all patients at baseline and 24 hours after starting treatment. All samples were collected in EDTA containing tubes and transported to the laboratory in ice in less than 15 minutes of collection.

Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) score and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores were calculated for all the patients. Cause of cirrhosis was obtained from past medical records. Major outcome was the change in HESA score after 24 hours. The patients were also compared regarding the length of hospital stay and blood ammonia levels and biochemical studies.

One of the team members was responsible for prescribing either PEG-lactulose or lactulose alone to eligible patients, while HESA scores at presentation and 24 hours later were calculated by another team member avoiding possible biases. The clinical evaluator had been experienced previously in the diagnosis of hepatic encephalopathy and in the performance of HESA. Also statistical analyses were done by another member who was totally masked to the treatment groups.

Primary outcome of this trial was defined as at least one scale improvement in HESA score. Secondary outcomes were overall length of hospital stay and changes in blood ammonia level.

IBM SPSS software version 22 for windows was used to analyze the data. We used Pearson Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test for qualitative analysis, Shapiro-Wilk test to assess normal distribution, independent sample Mann Whitney U test and Log Rank test for non-parametric analysis and independent sample t test for parametric analysis. A cut-off of 0.05 for statistical significance was presumed.

RESULTS

Of the 48 eligible patients to enter the study, 2 patients in each group refused to consent. Three patients in lactulose group and one patient in PEG-lactulose group had received sedative drugs. Since the diagnosis of hepatic encephalopathy is based on the exclusion of other diagnoses, we excluded their data from the final analysis.

Basic demographic data were similar between the groups (table 1). Hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and cryptogenic cirrhosis were the most common underlying causes of cirrhosis. There were no significant differences in the underlying etiology of cirrhosis. Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding and constipation were the most common precipitating factors of hepatic encephalopathy. No significant difference was seen in the precipitating factors of encephalopathy between the treatment groups. Severity of cirrhosis according to MELD score and CTP score was also comparable between the two groups. Three patients in lactulose group and two patients in PEG-lactulose group received lactulose enema (p =0.63).

Table 1. Basic demographic and clinical information .

| Variables |

All

Patients (n=40) |

Lactulose Group

(n=19) |

PEG-lactulose

Group (n=21) |

Significant Difference |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 56.45 (10.86) | 59.63 (9.24) | 53.57 (11.61) | No |

| Men, n | 27 | 11 | 16 | No |

| Cirrhosis Cause, n | No | |||

| Alcoholic fatty liver disease | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Cryptogenic | 11 | 6 | 5 | |

| Hepatitis B | 12 | 6 | 6 | |

| Hepatitis C | 9 | 4 | 5 | |

| NASH | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Portal thrombosis | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Encephalopathy Cause, n | No | |||

| Constipation | 15 | 9 | 6 | |

| Electrolyte disturbance | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| GI bleeding | 18 | 7 | 11 | |

| HCC | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Infection | 4 | 2 | 2 | |

| MELD score, median (IQR) | 17.5 (10) | 17.5 (6) | 17.5 (15) | No |

| CTP score, median (IQR) | 9 (3) | 9 (2) | 9.5 (3) | No |

| Lactulose enema, n | 5 | 3 | 2 | No |

NASH: non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma, CTP: Child-Turcotte-Pugh, MELD: Model of End-stage Liver Disease, PEG: polyethylene glycol 3350.

In addition, baseline lab data including blood level of ammonia was similar between PEG-lactulose group and lactulose group (tables 2 and 3).

Table 2. Laboratory data .

| Variables |

All

Patients (n=40) |

Lactulose Group

(n=19) |

PEG-lactulose

Group (n=21) |

Significant Difference |

| WBC count, mean (SD), × 109/L | 8.6 (5.8) | 9.8 (7.1) | 7.6 (4.2) | No |

| Hemoglobin concentration, mean (SD), mg/dL | 10.7 (2.5) | 10.7 (2.0) | 10.6 (2.9) | No |

| Platelet count, mean (SD), × 103/uL | 99.7 (59.5) | 98.0 (65.3) | 101.2 (55.3) | No |

| BUN, mean (SD), mg/dL | 35.7 (25.8) | 38.8 (25.5) | 32.8 (26.4) | No |

| Creatinine, mean (SD), mg/dL | 1.4 (0.8) | 1.5 (0.8) | 1.2 (0.6) | No |

| Total bilirubin, mean (SD), mg/dL | 7.3 (11.6) | 5.1 (7.9) | 9.3 (14.0) | No |

| Direct bilirubin, mean (SD), mg/dL | 3.7 (6.9) | 2.2 (3.9) | 5.1 (8.7) | No |

| Prothrombin time, mean (SD), sec | 21.8 (10.4) | 19.7 (7) | 23.7 (12.7) | No |

| Partial thromboplastin time, mean (SD), sec | 37.6 (17.4) | 35.6 (11.5) | 39.4 (21.6) | No |

| INR, mean (SD) | 1.8 (1.0) | 1.6 (0.6) | 2.0 (1.3) | No |

| Total protein, mean (SD), g/dL | 4.9 (0.8) | 4.8 (0.8) | 4.9 (0.7) | No |

| Serum albumin, mean (SD), g/dL | 2.8 (0.5) | 2.8 (0.5) | 2.8 (0.6) | No |

WBC, white blood cell; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; INR, international normalized ratio.

Table 3. Study outcomes .

| Variables |

All

Patients (n=40) |

Lactulose Group

(n=19) |

PEG-lactulose

Group (n=21) |

Significant

Difference |

| Baseline HESA score | 0.34 | |||

| 2 | 16 | 8 | 12 | |

| 1 | 24 | 11 | 9 | |

| 24-h HESA score change, mean (SD) | 1 (0.57) | 0.77 (0.53) | 1.23 (0.53) | *0.04 |

| One or more score improvement in HESA score, n | 34 | 14 | 20 | *0.05 |

| 24-h ammonia level change, mean (SD), µmol/L | ||||

| Baseline level | 77.6 (30.5) | 72.5 (28.4) | 82.1 (32.3) | 0.30 |

| After 24-h | 41.2 (25.5) | 37.0 (18.6) | 45.1 (30.4) | 0.55 |

| Difference | 36.3 (21.1) | 35.6 (17.8) | 37.0 (24.2) | 0.81 |

| Length of hospital stay, mean (SE), day | 7.8 (0.4) | 8.9 (0.7) | 6.8 (0.5) | *0.03 |

We used Mann Whitney U test to analyze “baseline HESA score”, “24-h HESA score change” and “24-h ammonia level change” due to lack of normal distribution. Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze “one or more score improvement in HESA score”. Data for “length of hospital stay” were analyzed using Log-rank test.

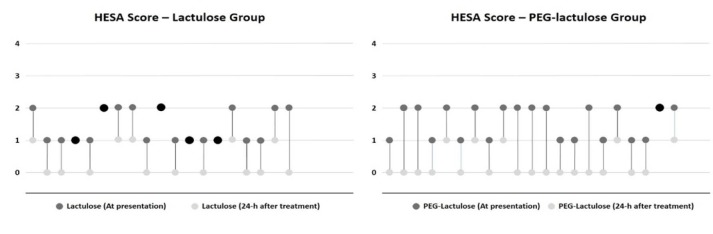

In comparison with lactulose alone, PEG-lactulose could improve HESA score in 24 hours more effectively (p =0.04, table 3). 20 patients in PEG-lactulose group had a decrease of at least 1 HESA score after 24 hours, as compared with 14 patients in lactulose group and the difference was significant (p =0.05, figure 1).

Fig. 1.

24-hour HESA score changes in lactulose and PEG-lactulose groups

HESA score at presentation and 24 hours after treatment have been shown with different bullet colors for each treatment group. Dark gray for the beginning and light gray for 24 hours after treatment. The patients whose HESA score did not show any changes after 24 hours have been shown with black bullets.

Of the 21 patients in PEG-lactulose arm, 1 patient had no improvement in HESA score, 14 patients had improvement of one score and 6 patients improved by two scores. Of the 19 patients in lactulose arm, 5 patients had no improvement in HESA score, 13 patients had improvement as much as one score and 1 patient had improvement up to two scores (figure 1).

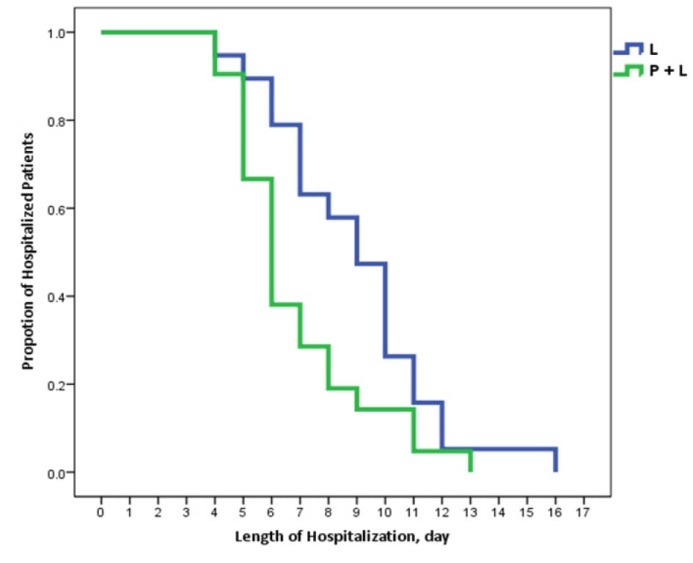

There was no significant change in the blood level of ammonia after 24 hours between the treatment groups (p =0.858, table 3). But, PEG-lactulose regimen was associated with a decrease in length of hospital stay as compared with lactulose treatment (p =0.03, figure 2).

Fig. 2.

Time to discharge in patients presented with hepatic encephalopathy(HE)

In a Kaplan-Meier graph, depicting the proportion of hospitalized patients and length of hospital stay for patients presented with hepatic encephalopathy. The patients who received PEG in addition to lactulose more rapidly discharged from hospital (p=0.03).

There were no notable adverse effects in either PEG-lactulose group or in lactulose group. Death did not occur in any of the groups up to the end of hospital discharge. There were not any significant changes in electrolyte levels and kidney functions as well.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study show that use of PEG along with lactulose in comparison with lactulose alone, is more effective in the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis. By accelerating the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy, PEG can help patients to return to normal life more rapidly and decrease the direct and indirect cost of illness caused by hepatic encephalopathy. PEG, which resolves decreased level of consciousness more effectively and more rapidly in the first 24 hours, can also help physicians to identify the other causes of altered mental status more quickly and more accurately.

The exact mechanism resulting in hepatic encephalopathy is poorly understood.28 Many studies have suggested the role of ammonia production in GI tract and impaired ammonia elimination by an imperfect liver 21,29; thus reduction in the amount of GI bacteria by the use of antibiotics and colon cleansing agents may play a therapeutic role in hepatic encephalopathy. This therapeutic strategy is dissociated with the underlying cause of hepatic encephalopathy i.e. whether GI bleeding or electrolyte disturbance was the precipitating factor, administration of cleansing agents might be helpful in resolving hepatic encephalopathy. PEG is a safe osmotic laxative most commonly used for colon preparation before colonoscopy and is an inexpensive, widely accessible laxative in many settings. Due to the past literature review, this randomized controlled trial could show the effectiveness of PEG in the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy for the second time. Compatible with a previous study 23, in this trial PEG-lactulose could improve hepatic encephalopathy more rapidly than lactulose alone, but there were no significant differences in blood level of ammonia between the two groups. Up to the best of our knowledge, ammonia or better to say NH3 (not NH4+) plays the major role in altered mental status in encephalopathic cirrhotic patients, because only NH3 can easily pass over blood brain barrier.30 If we measured the amount of free NH3 instead of total blood level of ammonia, we could probably find a difference between the two treatment groups. It is noteworthy that PEG causes a mild metabolic acidosis, resulting in increased NH4+ level and decreased NH3. These chemical changes might explain the effect of PEG in rapid improvement of altered mental status without any significant change in ammonia level.30,31 In addition, some other studies have challenged the use of blood ammonia as an indicator for severity of hepatic encephalopathy, especially in grade 0 to grade 2 encephalopathy.32-34

It is worth mentioning that because of GI bleeding, 7 patients in lactulose group and 11 patients in PEG-lactulose group (p =0.32) received ceftriaxone 1g daily for 3 days as a preventive strategy against spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Since there is no significant difference in the number of these patients between the two groups, we can assume that prophylactic antibiotic therapy did not confound the results of this trial.

There are some notable limitations in our study. This trial assessed the effect of PEG in only one hospital. In this trial, we used a unique dose of PEG, namely the same dose being used for preparing the colon for colonoscopy. More studies of escalating doses should be designed to reach the optimum dose of PEG with minimum adverse effects in the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy. Finally this was a non-inferiority trial; superiority trials that weigh PEG alone versus other conventional treatments like lactulose, help researchers to understand the effect of PEG much better.

This randomized controlled trial showed that the use of PEG together with lactulose in comparison with lactulose alone is a more effective way in the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis and results in more rapid discharge from hospital. Larger and multicenter trials with different doses of PEG and different target population should be performed to make PEG as a routine treatment for patients with cirrhosis and encephalopathy.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere thanks to Dr Mohamadreza Aghamirsalim and Dr Mani Beigi whose constructive comments enabled us to perform this trial much better.

Please cite this paper as:

Naderian M, Akbari H, Saeedi M, Sohrabpour AA. Polyethylene Glycol and Lactulose versus Lactulose Alone in the Treatment of Hepatic Encephalopathy in Patients with Cirrhosis: A Non-Inferiority Randomized Controlled Trial. Middle East J Dig Dis 2017;9:12-19. DOI: 10.15171/mejdd.2016.46

Footnotes

Source of funding: Digestive Disease Research Institute, Shariati Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

(Registration ID in IRCT.IR: IRCT2015083117719N2)

CONFLICT OF INTEREST The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this work.

References

- 1.Bajaj JS, Wade JB, Gibson DP, Heuman DM, Thacker LR, Sterling RK. et al. The multi-dimensional burden of cirrhosis and hepatic encephalopathy on patients and caregivers. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1646–53. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Minino AM. Death in the United States, 2011. NCHS Data Brief 2013:1-8. [PubMed]

- 3.GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;385:117–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis GL, Alter MJ, El-Serag H, Poynard T, Jennings LW. Aging of hepatitis C virus (HCV)-infected persons in the United States: a multiple cohort model of HCV prevalence and disease progression. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:513–21, 21. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zezos P, Renner EL. Liver transplantation and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:15532–8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i42.15532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poordad FF. Review article: the burden of hepatic encephalopathy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25 Suppl 1:3–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-6342.2006.03215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferenci P, Lockwood A, Mullen K, Tarter R, Weissenborn K, Blei AT. Hepatic encephalopathy--definition, nomenclature, diagnosis, and quantification: final report of the working party at the 11th World Congresses of Gastroenterology, Vienna, 1998. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 2002;35:716–21. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.31250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bajaj JS, Wade JB, Sanyal AJ. Spectrum of neurocognitive impairment in cirrhosis: Implications for the assessment of hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 2009;50:2014–21. doi: 10.1002/hep.23216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ortiz M, Jacas C, Cordoba J. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy: diagnosis, clinical significance and recommendations. J Hepatol. 2005;42 Suppl 1:S45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romero-Gomez M, Boza F, Garcia-Valdecasas MS, Garcia E, Aguilar-Reina J. Subclinical hepatic encephalopathy predicts the development of overt hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2718–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bajaj JS. Review article: the modern management of hepatic encephalopathy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:537–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prasad S, Dhiman RK, Duseja A, Chawla YK, Sharma A, Agarwal R. Lactulose improves cognitive functions and health-related quality of life in patients with cirrhosis who have minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 2007;45:549–59. doi: 10.1002/hep.21533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watanabe A, Sakai T, Sato S, Imai F, Ohto M, Arakawa Y. et al. Clinical efficacy of lactulose in cirrhotic patients with and without subclinical hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 1997;26:1410–4. doi: 10.1053/jhep.1997.v26.pm0009397979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nusrat S, Khan MS, Fazili J, Madhoun MF. Cirrhosis and its complications: evidence based treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:5442–60. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i18.5442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eltawil KM, Laryea M, Peltekian K, Molinari M. Rifaximin vs conventional oral therapy for hepatic encephalopathy: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:767–77. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i8.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kimer N, Krag A, Moller S, Bendtsen F, Gluud LL. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the effects of rifaximin in hepatic encephalopathy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:123–32. doi: 10.1111/apt.12803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang E, Esrailian E, Spiegel BM. The cost-effectiveness and budget impact of competing therapies in hepatic encephalopathy - a decision analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1147–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferenci P, Herneth A, Steindl P. Newer approaches to therapy of hepatic encephalopathy. Semin Liver Dis. 1996;16:329–38. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma BC, Sharma P, Agrawal A, Sarin SK. Secondary prophylaxis of hepatic encephalopathy: an open-label randomized controlled trial of lactulose versus placebo. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:885–91, 91. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blei AT, Cordoba J. Hepatic Encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1968–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Als-Nielsen B, Gluud LL, Gluud C. Non-absorbable disaccharides for hepatic encephalopathy: systematic review of randomised trials. BMJ. 2004;328:1046. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38048.506134.EE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blanc P, Daures JP, Liautard J, Buttigieg R, Desprez D, Pageaux G. et al. [Lactulose-neomycin combination versus placebo in the treatment of acute hepatic encephalopathy Results of a randomized controlled trial] Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1994;18:1063–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rahimi RS, Singal AG, Cuthbert JA, Rockey DC. Lactulose vs polyethylene glycol 3350--electrolyte solution for treatment of overt hepatic encephalopathy: the HELP randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1727–33. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bircher J, Muller J, Guggenheim P, Haemmerli UP. Treatment of chronic portal-systemic encephalopathy with lactulose. Lancet. 1966;1:890–2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(66)91573-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doran AE, Shah NL. Polyethylene glycol for hepatic encephalopathy: a new solution to purge an old problem? JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1734–5. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elkington SG, Floch MH, Conn HO. Lactulose in the treatment of chronic portal-systemic encephalopathy A double-blind clinical trial. N Engl J Med. 1969;281:408–12. doi: 10.1056/nejm196908212810803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hassanein T, Blei AT, Perry W, Hilsabeck R, Stange J, Larsen FS. et al. Performance of the hepatic encephalopathy scoring algorithm in a clinical trial of patients with cirrhosis and severe hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1392–400. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones EA, Mullen KD. Theories of the pathogenesis of hepatic encephalopathy. Clin Liver Dis. 2012;16:7–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sturgeon JP, Shawcross DL. Recent insights into the pathogenesis of hepatic encephalopathy and treatments. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;8:83–100. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2014.858598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kramer L, Tribl B, Gendo A, Zauner C, Schneider B, Ferenci P. et al. Partial pressure of ammonia versus ammonia in hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md) 2000;31:30–4. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gabduzda GJ, Hall PW 3rd. Relation of potassium depletion to renal ammonium metabolism and hepatic coma. Medicine (Baltimore) 1966;45:481–90. doi: 10.1097/00005792-196645060-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blanco Vela CI, Bosques Padilla FJ. Determination of ammonia concentrations in cirrhosis patients-still confusing after all these years? Ann Hepatol. 2011;10Suppl 2:S60–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lockwood AH. Blood ammonia levels and hepatic encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis. 2004;193-4:345–9. doi: 10.1002/hep.510380529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang V, Saab S. Ammonia levels and the severity of hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Med. 2003;114:237–8. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(02)01571-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]