Abstract

From 1919 to 1952, approximately 20 000 individuals were sterilized in California’s state institutions on the basis of eugenic laws that sought to control the reproductive capacity of people labeled unfit and defective.

Using data from more than 19 000 sterilization recommendations processed by state institutions over this 33-year period, we provide the most accurate estimate of living sterilization survivors. As of 2016, we estimate that as many as 831 individuals, with an average age of 87.9 years, are alive.

We suggest that California emulate North Carolina and Virginia, states that maintained similar sterilization programs and recently have approved monetary compensation for victims. We discuss the societal obligation for redress of this historical injustice and recommend that California seriously consider reparations and full accountability.

In the first half of the 20th century, approximately 20 000 individuals were sterilized in California’s state homes and hospitals on the basis of eugenic laws designed to control the reproduction of people labeled mentally defective. Using data from more than 19 000 sterilization recommendations processed by California institutions from 1919 to 1952, we provide the most statistically rigorous estimate to date of the likely living survivors of California’s sterilization program.

Given the relevance of public health policies and institutions to the compulsory sterilization of thousands of individuals deemed “unfit” to reproduce, we suggest that public health advocates committed to social and reproductive justice can play a leading role in addressing this historical injustice and its contemporary legacies. We call for societal accountability toward the dwindling number of living survivors and propose that California follow the lead of North Carolina and Virginia in providing redress to those affected by state-mandated reproductive constraints.

BACKGROUND

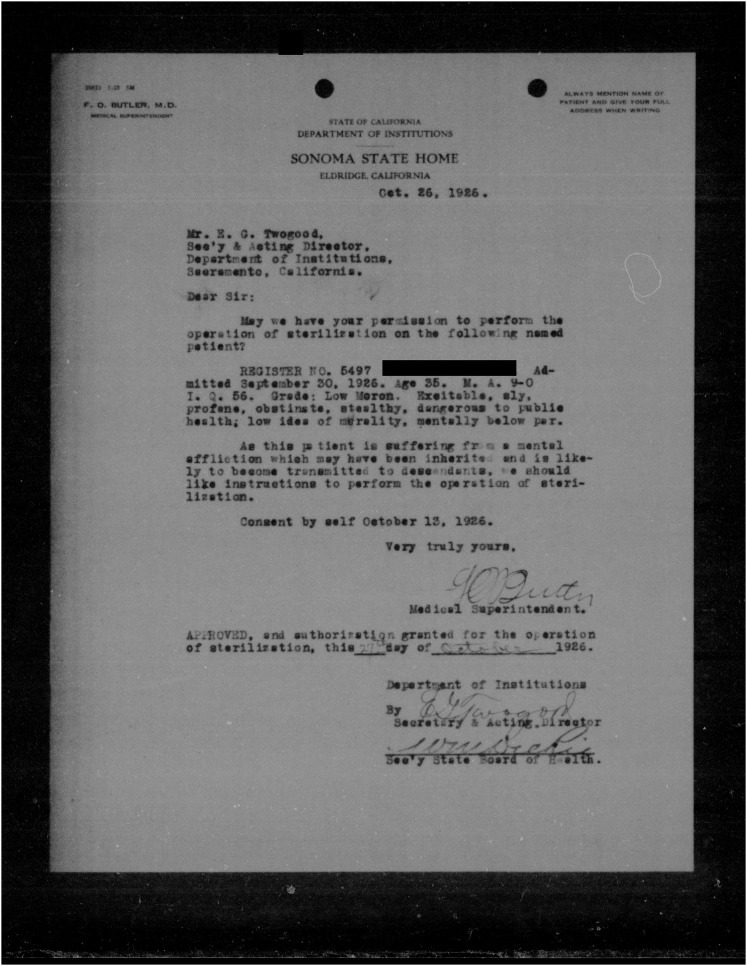

In 1926, Marsha (all names are pseudonyms) was admitted to the Sonoma State Home in California and recommended for sterilization because of her IQ score of 56, which placed her in the category of “low moron [sic]” (Figure 1). Given this diagnosis and because she was “sly, profane, [and] obstinate,” the medical superintendent determined that Marsha was “dangerous to public health” and, therefore, should be sterilized. Marsha was but one of approximately 20 000 people affected by a law passed in 1909 that authorized such reproductive surgery on patients committed to state homes or hospitals and judged to be suffering from a “mental disease which may have been inherited” and was “likely to be transmitted to descendants.”1(p57),2,3

FIGURE 1—

Redacted Sterilization Recommendation, October 26, 1926

Note. This record was used in accordance with the institutional review board protocols of the California Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects and the University of Michigan.

On the books until 1979, this statute provided the legal framework for the most active sterilization program in the United States. California’s sterilization law authorized medical superintendents to perform the operation without consent.4–6 Nevertheless, institutional authorities did seek written consent from a family member or legal guardian when possible, probably as a result of liability concerns. Yet, the prison-like environment of state institutions during this era raises serious questions about the validity of the consent process. Notably, sterilization was a prerequisite for release from some institutions.

Confirming genuine consent is complicated because signatures, dates, and names on consent forms are often inconsistent with information in patient records. The documents themselves do not always record when or whether the operation was actually performed. In addition, we identified multiple efforts by families and patients themselves to prevent sterilization. Although some sterilizations may have been performed with the signed consent of a parent or guardian, these procedures did not meet the standards of voluntary consent, and in many cases people were sterilized against their will. Although California was the most aggressive sterilizer, information about the likely number of living victims is scant because of the paucity of large-scale data sources and the silence of the victims themselves.

As of 2016, we estimate that as many as 831 patients sterilized in California institutions are alive today. Producing this estimate is one facet of a larger interdisciplinary project devoted to demographic and historical reconstructions of eugenics and sterilization in California. Given public health’s commitments to social and reproductive justice, we believe that public health offers a useful lens for coming to terms with this past injustice. By providing the most rigorous estimate of sterilization survivors in California to date, we hope to spark a conversation about potential opportunities for recognition and redress.

EUGENICS AND EUGENIC STERILIZATION

During the first half of the 20th century, eugenics was a popular “science” in the United States and throughout the world that influenced many public health policies and programs.7–9 In 1907 Indiana passed the world’s first eugenic sterilization law, which authorized medical superintendents to sterilize inmates whose supposed deleterious heredity appeared to threaten society.10 From 1907 to 1937, 32 US states passed eugenic sterilization laws as part of a larger public health effort to combat degeneracy. Sterilization rates, which remained fairly steady in the 1910s and early 1920s as eugenics gained currency, increased markedly after the 1927 Buck v. Bell US Supreme Court decision (274 US 200), which upheld the constitutionality of Virginia’s sterilization law.4 California passed the third law in the nation in 1909 and performed one third of all officially reported operations nationwide from the 1910s to the 1960s.4,5

Although the strident racism and primitive theories of heredity associated with the eugenics movement receded after World War II (1939–1945), state legislatures did not start to repeal these statutes until the 1970s. During the six decades they were in force, more than 60 000 sterilizations were officially recorded, principally in state homes and hospitals for the “feebleminded” and “insane.”6 Sterilization laws had the effect of depriving individuals marginalized in US society of their reproductive rights.11,12

Today, scholars and the lay public recognize eugenic sterilization as one of the most severe manifestations of eugenics, as an ethical wrong that deprived thousands of people their reproductive autonomy without bona fide consent.13–16

The logic of public health protection informed eugenic sterilization. For example, the language in Marsha’s recommendation made explicit the underlying assumption that individuals deemed “unfit” or “dangerous to public health” required reproductive control. Just one year after Marsha’s case, the Buck v. Bell (1927) decision foregrounded arguments about the need to protect the public’s health and invoked smallpox vaccination as an analogous common good. In explaining the state’s duty to sterilize Carrie Buck, a patient in Virginia's Lynchburg Colony and “the probable potential parent of socially inadequate offspring,” Chief Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. argued that sterilization and immunization were synonymous public health protections: “the principle that sustains compulsory vaccination is broad enough to cover cutting the fallopian tubes.”7(pp168,169)

SURVIVOR ESTIMATES AND DESCRIPTIONS

A longer explanation of our methods is included as a methodological appendix available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org. Briefly, we used sterilization recommendation forms discovered on 19 microfilm reels in the offices of the California Department of Mental Health (now Department of State Hospitals) to construct a data set with information about 19 995 individuals recommended for sterilization in California state hospitals between 1919 and 1952; 19 498 records had adequate data for our analysis.

This data source was valuable for our purposes because it provided individual-level information on the age and sex of each person recommended for sterilization, not only the number of procedures per year. We used sex-specific life tables (1920–2010) from the National Center for Health Statistics to estimate the probability of each individual surviving to the present, accounting for sex, age, and year of sterilization. We applied an adjustment factor to our estimate to account for the fact that some individuals recommended for sterilization may not have ultimately undergone the procedure.

We estimate that the total number of survivors in 2016 is 831 (511 women and 320 men), with the largest percentage (48.5%) sterilized between 1945 and 1949. The majority of survivors (566, or 68.1%) were sterilized at age 17 years or younger. Survivors’ average age as of 2016 is estimated to be 87.9 years (Table 1).

TABLE 1—

Numbers of Residents of California State Homes and Hospitals Recommended for Sterilization Between 1919 and 1952 and Estimated Surviving Population in 2016

| Variable | Recommended for Sterilization (n = 19 498), No. (%) | Estimated Survivors in 2016 (n = 831), No. (%) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 9586 (49) | 320 (38) |

| Female | 9912 (51) | 511 (62) |

| Year recommended for sterilization | ||

| 1919–1924 | 1998 (10) | 0 (0) |

| 1925–1929 | 3402 (17) | 0 (0) |

| 1930–1934 | 3418 (18) | 11 (1) |

| 1935–1939 | 4391 (23) | 78 (9) |

| 1940–1944 | 3579 (18) | 227 (27) |

| 1945–1949 | 2306 (12) | 403 (49) |

| 1950–1952 | 404 (2) | 111 (13) |

| Age at sterilization recommendation, y | ||

| < 12 | 37 (0) | 3 (<1) |

| 12–14 | 925 (5) | 141 (17) |

| 15–17 | 3597 (18) | 421 (51) |

| 18–19 | 1782 (9) | 121 (15) |

| 20–24 | 3478 (18) | 109 (13) |

| 25–29 | 3273 (17) | 31 (4) |

| 30–34 | 2867 (15) | 3 (<1) |

| 35–39 | 2170 (11) | 0 (0) |

| 40–44 | 919 (5) | 0 (0) |

| 45–49 | 321 (2) | 0 (0) |

| ≥ 50 | 129 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Age in 2016, y | ||

| 75–79 | … | 8 (1) |

| 80–84 | … | 218 (26) |

| 85–89 | … | 310 (37) |

| 90–94 | … | 209 (25) |

| 95–99 | … | 78 (9) |

| ≥ 100 | … | 5 (1) |

Note. Percentages might not add to 100 because of rounding.

The life expectancy of some of the institutional residents recommended for sterilization may differ from the life expectancy of the general population of California because individuals were institutionalized ostensibly as a result of mental illness or developmental disability. Although the extent to which institutional residents differed from the general population is uncertain, the number of survivors is likely still in excess of 500 even if our method has overestimated survival.

Most of the estimated survivors were sterilized in the late 1940s, a period when eugenic efforts most aggressively targeted those labeled “feebleminded.” Often these young people were considered sexual or criminal delinquents or came from families that were dependent on state aid or local charities.

For example, Sarah was in her early teens when she was admitted to Sonoma State Hospital in the late 1940s after her family was no longer able to care for her. Officials sterilized Sarah because of her supposed sexual delinquency and poor family attributes, including poverty and alcoholism. Now in 2016, Sarah would be in her early 80s.

Young men were likely to find themselves under scrutiny for criminal delinquency or loosely defined irresponsible behavior. Joseph was admitted to Pacific Colony after showing violent tendencies toward his mother. Despite being determined to have borderline intelligence, a designation that rarely warranted sterilization, Joseph’s recklessness, familial history of adultery, and other “hereditary causes” ultimately led to his sterilization. As with many other young people, Joseph was released on parole shortly after sterilization.

JUSTICE FOR STERILIZATION VICTIMS

Human rights and legal scholars have debated instances of injustice that merit more than a simple apology, such as slavery, internment, and genocide. The ethical principles that one legal scholar provides for determining when society is obliged to provide redress to a group of people include that “a human injustice must have been committed” and that said injustice “must be well documented.”17(p7) In 2003, California officials publicly apologized for the state-run sterilization program, acknowledging the thousands of surgeries as a human injustice.18 In addition to state counts of the number of sterilizations, our data and archive include official records and requests that fully document the sterilizations and the biased eugenic logic used to justify them. Given the principles outlined by legal scholars guiding “meritorious redress claims,” the state’s own admission of injustice, and the documented impact of sterilization on people with disabilities and from poor backgrounds, it is reasonable to conclude that what happened in California warrants more than a public apology, especially given the state’s high sterilization numbers.19

Guided by our estimate of the number of living sterilization survivors, we suggest that California emulate its sister states, North Carolina and Virginia, and launch monetary compensation programs for victims.20 Both North Carolina and Virginia have created agencies (the North Carolina Office of Justice for Sterilization Victims and the Virginia Eugenical Sterilization Act Compensation Program) to process and adjudicate claims for compensation, which were set at $20 000 and $25 000, respectively.

Recent efforts in these two states underscore the merit of compensating individuals who have experienced state-sanctioned reproductive injustice. In 2013, after years of organizing by sterilization survivors and supportive legislative officials, North Carolina, which sterilized approximately 8000 people in the 20th century, passed a law to compensate victims.12

North Carolina’s State Center for Health Statistics used life table methods similar to our own to estimate that there were as many as 2944 living survivors of the North Carolina Eugenics Board’s sterilization program in 2010 (although adjustment for lower life expectancy among groups targeted for sterilization reduced the final estimate of survivors to 1500–2000). Although North Carolina performed fewer total sterilizations than California, its estimate of living survivors is higher because eugenic sterilizations occurred more recently, well into the 1960s.

A $10 million fund was appropriated to correspond to the number of victims deemed eligible for compensation. The state’s Office of Justice for Sterilization Victims required that victims be alive on June 30, 2013, and it accepted claims through June 30, 2014. The state approved 220 of 768 claims and sent out $20 000 checks to verified claimants. The legislation required proof that the procedure was approved by the North Carolina Eugenics Board, and thus some individuals sterilized by private physicians, even those with eugenic intent, were ineligible for compensation. A bill proposed in the state legislature earlier this year would make additional reparations available to some of these victims.21

In Virginia, where about 7600 people were sterilized in state institutions during the 20th century, the Christian Law Institute pushed for legislation, established the Justice for Sterilization Victims Project, and lobbied the legislature for monetary compensation following the example of North Carolina.22 The number of survivors in Virginia was estimated to be approximately 1500 on the basis of North Carolina’s calculation that approximately 20% of initial victims had survived to the present day. In 2015, the state set aside $400 000 to compensate survivors with awards of approximately $25 000 each.22 The Virginia Eugenical Sterilization Act Compensation Program required that victims be alive on February 1, 2015, and the program continues to accept claims.

One concern in both states has been whether receipt of reparations would count toward individuals’ income and make them ineligible for federal programs such as Medicaid or the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. A bill recently passed in the US House of Representatives would ensure that state-level eugenics reparations do not interfere with the benefit eligibility of this aging and vulnerable population.23

While North Carolina and Virginia were organizing compensation programs, a new episode of sterilization abuse emerged in California, this time among women incarcerated in state prisons. A 2013 Center for Investigative Reporting article revealed that, between 2006 and 2010, close to 150 unauthorized sterilizations were performed in California prisons.24 In response, Senator Hannah-Beth Jackson requested an investigation by the California state auditor that corroborated and expanded the article’s findings, showing that 144 women were sterilized without adherence to required protocols.25

Prejudices expressed by Dr. James Heinrich, the physician who performed many of the tubal ligations, were particularly revealing. He told a reporter that the money spent sterilizing inmates was negligible “compared to what you save in welfare paying for these unwanted children—as they procreated more.”24 This callous attitude toward the reproductive lives of institutionalized women, the majority low-income women and women of color, echoed earlier eugenic attitudes. In the 1930s, at the height of eugenic sterilization, California’s health officials repeatedly asserted that, in addition to its therapeutic value, sterilization would relieve the state of the economic burden of “defectives” and their progeny.

Senator Jackson connected the prison sterilizations to California’s past when she stated that “pressuring a vulnerable population—including at least one instance of a patient under sedation[—]to undergo these extreme procedures erodes the ban on eugenics.”25 This recent news and Senator Jackson’s comments point to the importance of recognizing the long history of sterilization abuse involving vulnerable individuals in California.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite the sustained attention and political response to the recent prison sterilizations in California, there is little public conversation addressing the hundreds of victims of the state’s protracted 20th-century eugenic program who are likely alive today. From the 1920s to the 1950s, tens of thousands of people were wronged by misguided public health policies that resulted in compulsory sterilization. The remaining survivors of California’s eugenic sterilization program deserve further societal acknowledgment and redress.

Given the advanced age and declining numbers of sterilization survivors, time is of the essence for the state to seriously consider reparations. California should explore the possibility of producing a eugenic sterilization registry, locating living individuals, and offering monetary compensation. We suggest that interested stakeholders, including public health advocates, legislators, reproductive justice and disability rights activists, and survivors willing to come forward, move quickly to ensure that California takes steps toward reparations and full accountability for this past institutional and reproductive injustice.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the University of Michigan M-CUBED program for pilot support to create the eugenic sterilization data set. Siobán Harlow gratefully acknowledges use of the services and facilities of the Population Studies Center at the University of Michigan, funded by grant R24 HD041028 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

We thank Paul Lombardo for suggesting that we undertake a systematic analysis of living sterilization survivors in California, Barbara Anderson for consultation on life table analyses, two anonymous reviewers for incisive comments, and Mark A. Rothstein (department editor for public health ethics, AJPH) for constructive feedback on earlier versions.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The institutional records analyzed for this study were used in accordance with the institutional review board protocols of the California Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects and the University of Michigan.

Footnotes

See also Reverby, p. 14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Braslow J. Mental Ills and Bodily Cures: Psychiatric Treatment in the First Half of the Twentieth Century. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kline W. Building a Better Race: Gender, Sexuality, and Eugenics from the Turn of the Century to the Baby Boom. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stern AM. Eugenic Nation: Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in America. 2nd ed. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Largent MA. Breeding Contempt: The History of Sterilization in the United States. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stern AM. Sterilized in the name of public health: race, immigration, and reproductive control in modern California. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(7):1128–1138. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.041608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wellerstein A. States of eugenics: institutions and practices of compulsory sterilization in California. In: Jasanoff S, editor. Reframing Rights: Bioconstitutionalism in the Genetic Age. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2011. pp. 29–58. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lombardo P. Three Generations, No Imbeciles: Eugenics, the Supreme Court, and Buck v. Bell. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paul DB. Controlling Human Heredity: 1865 to the Present. Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Humanities Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kevles DJ. In the Name of Eugenics: Genetics and the Uses of Human Heredity. 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stern AM. We cannot make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear: eugenics in the Hoosier heartland, 1900–1960. Indiana History Magazine. 2007;103(1):3–38. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansen R, King DS. Sterilized by the State: Eugenics, Race, and the Population Scare in Twentieth-Century North America. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Begos K, Deaver D, Railey J, Sexton S. Against Their Will: North Carolina’s Sterilization Program and the Campaign for Reparations. Apalachicola, FL: Gray Oak Books; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buchanan A, Brock DW, Daniels N, Wikler D. From Chance to Choice: Genetics and Justice. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Comfort N. The Science of Human Perfection: How Genes Became the Heart of American Medicine. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehlman M. The Price of Perfection: Individualism and Society in the Age of Bioenhancement. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knoepfler P. GMO Sapiens: The Life-Changing Science of Designer Babies. Hackensack, NJ: World Publishing Company; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brooks RL, editor. When Sorry Isn’t Enough: The Controversy Over Apologies and Reparations for Human Justice. New York, NY: New York University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alpert D. California’s Compulsory Sterilization Policies, 1909–1979. Sacramento, CA: Senate Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nobles M. The Politics of Official Apologies. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.West KA. Following in North Carolina’s footsteps: California’s challenge in compensating its victims of compulsory sterilization. Santa Clara Law Rev. 2013;301(53):301–327. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell C, Helms D. More North Carolina eugenics victims could become eligible for compensation. Available at: http://www.newsobserver.com/news/politics-government/state-politics/article82871452.html. Accessed October 1, 2016.

- 22.Sizemore B. Virginia to compensate victims of forced sterilizations. Available at: http://wsls.com/2015/02/27/virginia-to-compensate-victims-of-forced-sterilizations/. Accessed January 12, 2016.

- 23.Ellis K. Eugenics bill passes House. Available at: http://www.shelbystar.com/news/20160707/eugenics-bill-passes-house. Accessed October 1, 2016.

- 24.Johnson CG. Female inmates sterilized in California prisons without approval. Available at: http://cironline.org/reports/female-inmates-sterilized-california-prisons-without-approval-4917. Accessed October 1, 2016.

- 25.California State Auditor. Sterilization of female inmates. Available at https://www.auditor.ca.gov/pdfs/reports/2013-120.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2016.