Abstract

Purpose

We examined if residential segregation (degree to which racial/ethnic groups live separately from one another in a geographic area): 1) Was associated with mortality among urban breast cancer patients; 2) Explained racial/ethnic disparities in mortality; and 3) If its association with mortality varied by race/ethnicity.

Methods

Using Texas Cancer Registry data, we examined all-cause and breast-cancer mortality of 109,749 urban, female, Black, Hispanic, and White breast cancer patients ≥50 years, and diagnosed 1995-2009. We measured racial (Black) and ethnic (Hispanic) segregation of patient's neighborhood compared to their larger MSA using the Location Quotient measure. Shared frailty Cox proportional hazard models nested patients within residential neighborhoods (census tract) and controlled for race/ethnicity, age, diagnosis year, tumor stage, grade, histology, neighborhood poverty, and county-level mammography availability.

Results

Greater Black and Hispanic segregation were adversely associated with cause-specific and all-cause mortality. For example, in adjusted models, Hispanic segregation was associated with cause-specific mortality (aHR: 1.24; 95% CI: 1.05-1.46). When compared to Whites, Blacks had higher mortality for both outcomes, while Hispanics demonstrated equivalent (cause-specific) or lower (all-cause) mortality. Segregation did not explain racial/ethnic disparities in mortality. Within each race/ethnicity strata, segregation was either adversely associated with mortality or was not significant.

Conclusions

Among urban breast cancer patients in Texas, segregation has an independent adverse association on mortality and the effect of segregation varies by patient race/ethnicity. Our novel application of a small-area measure of relative racial segregation should be examined in other cancer types with documented racial/ethnic disparities across varied geographic areas.

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the second leading cause of cancer death among women in the U.S.1 Numerous studies have documented persistent racial/ethnic disparities in breast cancer mortality. Breast cancer disproportionately affects Black women. Between 2004-2008, for example, U.S. data demonstrate that Black women experienced higher mortality rates (32.0 per 100,000) than White women (22.8 per 100,000) and Hispanic women (15.1 per 100,000).1

Many observers consider residential racial/ethnic segregation—that is, the degree to which groups live separately from one another in a geographic area2—to be a fundamental cause of racial/ethnic disparities in health in the U.S., including cancer disparities.3 Residential racial segregation (hereafter “segregation”) may influence early breast cancer detection, cancer care delivery, and mortality. Extant research focuses on Black-White segregation and displays mixed findings. So while some studies found greater Black-White segregation associated with adverse outcomes4,5, others found mixed effects depending on patient race6,7, and still others found no statistically significant associations whatsoever.8 Meanwhile, segregation's influence on breast cancer outcomes among Hispanics remains largely unknown. Emerging evidence suggests that neighborhood effects observed in prior studies may not be generalizable to Hispanics. In some studies to date, although not all9, neighborhoods with a greater percentage of Hispanics were associated with improved cancer and other health outcomes.10-12

These mixed findings may stem from conceptual and methodological differences in measuring segregation.13 The two main measures of racial segregation across the health literature are: 1) Large-area (e.g. county, metropolitan statistical area [MSA]), formal segregation measures (e.g. MSA dissimilarity index) or 2) Neighborhood composition measures (e.g. census tract percent Black), considered a proxy measure of segregation.13 Conceptually, large-area segregation measures do not reflect daily, lived experience of residents in a neighborhood. Likewise, neighborhood composition measures, while simple to calculate, implicitly assume that the composition of one neighborhood is independent of the spatial distribution of race in nearby neighborhoods and across the greater MSA. This assumption runs counter to conceptual definitions that explicitly define segregation as a spatial phenomenon and assertions that “only dispersion measures are proper measures of segregation.”14 Methodologically, large-area segregation measures are complex to calculate and interpret, requiring specialized software and training.

A novel, recently introduced measure, the Location Quotient of Residential Racial Segregation (LQ)15, overcomes many of these limitations. The LQ is a small area measure of relative segregation calculated at the residential census tract level. It represents how much more segregated a patient's neighborhood (census tract) is relative to the larger overall metropolitan area (MSA). Thus, the LQ is a ratio of two proportions; the proportion of population group m in the tract (numerator) and the proportion of population group m in the MSA (denominator). The LQ does not require specialized software or skills to calculate, and explicitly measures relative, not absolute, segregation.

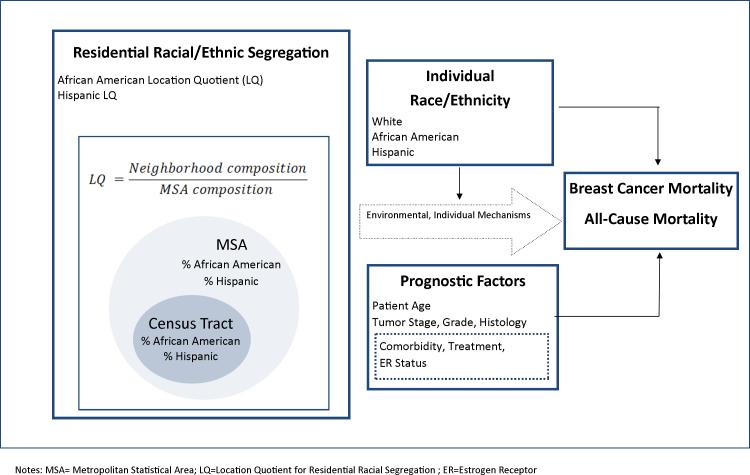

We incorporated this novel measure into a conceptual and measurement model of the relationships between segregation, individual race/ethnicity, and mortality for breast cancer patients (Figure 1). We developed the model and measures using existing conceptual frameworks and literature reviews on the health effects of segregation13,16-18 and breast cancer disparities19,20 as well as empirical evidence on segregation and breast cancer outcomes.4-8,21

Figure 1.

Conceptual and Measurement Model of Relationships between Residential Racial/Ethnic Segregation, Individual Race/Ethnicity, and Mortality for Breast Cancer Patients.

Our model (Figure 1) has two notable features. First, we explicitly define LQ as a measure of the relative segregation of the neighborhood compared to the segregation of the larger metropolitan area. While the LQ incorporates absolute measures of racial/ethnic composition, it more closely mirrors conceptual definitions of segregation as a relative, contextual phenomenon best captured with measures of dispersion. Second, we posit that segregation directly affects breast cancer mortality5-7,13,17 and that patient race/ethnicity moderates the association between segregation and mortality. Prognostic factors (e.g. age) and associated tumor factors (e.g. stage) are also in the model as important predictors of mortality. Dotted lines indicate variables unmeasured in the current study. These include the multiple environmental and individual mechanisms through which segregation “gets under the skin” to adversely influence health outcomes. While the mechanisms linking segregation and health have not been fully elucidated, they may include high unemployment, low income, deteriorated housing, poor quality schools, as well as lower quality and poorer access to health care facilities.2,3,22,23

Using this model as a guide, we examined the association of residential racial segregation and mortality among Black, Hispanic, and White urban breast cancer patients diagnosed in Texas, 1995-2009. Specifically, we addressed the following questions:

-

1)

Is greater segregation associated with higher mortality?

-

2)

To what extent does segregation explain racial/ethnic disparities in mortality?

-

3)

Does patient race/ethnicity moderate the association between segregation and mortality?

METHODS

Data and Sample

We obtained data from the Texas Cancer Registry (TCR), a North American Association of Central Cancer Registries (NAACCR) Gold-Certified population-based registry. We included female adult (≥50 years old) breast cancer patients diagnosed 1995-2009 who lived in a metropolitan statistical area (MSA). We selected women aged 50 and older to minimize population heterogeneity, as prognostic and demographic characteristics of young (<50 years old) breast cancer patients differ from older patients. We chose patients living in an MSA (using year 2003 MSA definitions) per common practice15,17 because MSAs represent the regional labor and housing markets by which segregation is created and sustained. We limited data to patients with a first primary cancer, known diagnosis date, and known cancer stage. Using latitude and longitude of patient residence at diagnosis (data were geocoded by TCR), we merged year 2000 U.S. Census data obtained from Geolytics and county-level year 2000 mammography machine data obtained from a freedom of information request to the FDA (requested July 2008, received March 2009). The Institutional Review Boards at UT Southwestern Medical Center, TCR, and Texas Department of Health and Social Services all approved this study.

Outcomes

We assessed two outcomes: cause-specific (breast cancer) and all-cause mortality. Time to event (survival time) was calculated as months between diagnosis date and date of death, and censored those alive on December 31, 2011. For the cause-specific analysis, we censored deaths from other causes. The TCR ascertained vital status, cause of death, and date of death using annual linkage to the National Death Index, Social Security Death Master File, and other vital status sources.

Segregation

We measured segregation using the Location Quotient for Residential Racial Segregation (LQ) (see Figure 1).15 LQ quantifies the relative homogeneity of each census tract within the overall MSA. Census tracts are the most commonly used approximation for neighborhood units and we hereafter refer interchangeably to “census tracts” and “neighborhoods”.

LQ can be calculated for any two groups; we measured the relative distribution of 1) non-Hispanic Blacks to non-Hispanic Whites, and 2) Hispanics (of any race) compared to non-Hispanic Whites (see Figure 1). We calculated LQ as:

| (1) |

Where LQim is the value of the ith tract in a MSA for population group m; xim is the number of residents of the mth group living in the ith tract; Xi is the total number of residents in the ith tract of the MSA; Ym is the total number of individuals of the population mth group in the MSA; and Y is the total number of MSA residents. LQ ranges from 0 to infinity; 0 indicates there are no residents of group M in the neighborhood. Values less than 1 indicate the neighborhood proportion of group M is less than the proportion of the same group in the larger MSA. In Sudano et al's example, a neighborhood with an LQ of 5 indicates that the neighborhood proportion of group M is 5 times the proportion of the same group in the MSA.15

Patient Race/ethnicity

We measured patient race/ethnicity as follows: non-Hispanic White (hereafter “White”), non-Hispanic Black (hereafter “Black”), and Hispanic (of any race). Race and ethnicity of patients was classified using two NAACCR measures: “Race 1” and “Spanish/Hispanic Origin” obtained from TCR.

Covariates

To adjust for additional factors that may influence mortality, we measured the following patient and tumor variables: age (continuous), SEER summary stage (in situ, local, regional, distant), diagnosis year (1995-97, 1998-00, 2001-03, 2004-06, 2007-09), tumor grade (low, high, unknown differentiation) histology (lobular, ductal, other, unknown). We measured neighborhood poverty as the percent of residents living in poverty in the patient's residential census tract. We measured access to breast cancer screening using the number of mammography machines per 10,000 women aged ≥50 years in the patient's county of residence.

Analyses

We conducted descriptive analyses for the total population and separately by patient race/ethnicity. We examined distribution of segregation, vital status, and covariates using chi-square and ANOVA. We calculated Spearman correlation coefficients to elucidate relationships between LQ measures and patient race/ethnicity. Because the LQ is an asymmetric measure with a right skew (ranging from 0 to infinity), scale-contracting transformations were considered. To avoid the value of log(x) from approaching negative infinity as the value × approaches zero, the log(x+1) transformation was used for the remainder of all analyses.24,25 To assess the association of segregation on mortality (Question 1), we fitted two Cox Proportional Hazard26 models for each outcome (cause-specific and all-cause mortality). We first fitted a univariate model (Model 1) to examine the main effects of segregation and patient race/ethnicity on mortality. Next, to examine the effect of adjusting for prognostic variables, we added all covariates to the model (Model 2).

To examine the extent to which segregation explains racial/ethnic disparities in mortality (Question 2), we repeated the fully adjusted Cox model without inclusion of the segregation variables (Model 3). We then compared any change in the main effect of race/ethnicity between Models 2 and 3 (with and without segregation).

To test whether patient race/ethnicity moderated the association of segregation and mortality (Question 3), we added interaction terms (2 Black/Hispanic LQ measures * 2 Black/Hispanic patient race measures) to Model 3 and compared the series of interaction models to Model 3 using likelihood ratio tests. To evaluate effect moderation, we fitted proportional hazard models stratified by race/ethnicity. First, we fitted univariate models (Model 4). Next, for all segregation variables significant (p<.05) in Model 4, we fitted multivariate models including all covariates (Model 5).

All Cox proportional hazard models were fitted as shared frailty models (i.e., included random effects accounting for clustering of patients within their residential census tracts) using the survival package in R 3.0.2.27 This is important because residents of the same census tracts may be more similar than those from other tracts and failure to account for the hierarchical nature of data using multilevel analyses can lead to negatively biased standard errors and spuriously significant results.28 Descriptive analyses were conducted in SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., NC, USA).

RESULTS

Overall, we included 109,749 Texas women diagnosed with breast cancer between 1995 and 2009 in the analysis. Women were distributed across 3,668 census tracts, including 82,089 Whites, 11,253 Blacks, and 16,407 Hispanics. Overall, 9,131 deaths from breast cancer and 33,458 deaths from all causes were observed during the study period, which included 780,698 person-years of follow-up. The distribution of vital status, segregation, and all covariates by patient race/ethnicity are provided in Table 1. All measures were significantly different (p<.05) by race/ethnicity.

Table 1.

Distribution of Patient, Tumor, and Neighborhood Characteristics by Patient Race/Ethnicity among Breast Cancer Patients (n=109,749) diagnosed in Texas, 1995-2009

| Total (n=109,749) | White (n=82,089) | Black (n=11,253) | Hispanic (n=16,407) | p (chi2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Vital status | |||||

| Cause-specific mortality | 9,131 (8.3) | 5,937 (7.2) | 1,591 (14.1) | 1,603 (9.8) | <.0001 |

| All-cause mortality | 33,458 (30.5) | 24,655 (30.0) | 4,159 (37.0) | 4,644 (28.3) | <.0001 |

| Diagnosis Year | |||||

| 1995-1997 | 17,933 (16.3) | 13,999 (17.1) | 1,616 (14.4) | 2,318 (14.1) | <.0001 |

| 1998-2000 | 21,221 (19.3) | 16,468 (20.1) | 1,889 (16.8) | 2,864 (17.5) | |

| 2001-2003 | 22,490 (20.5) | 17,070 (20.8) | 2,188 (19.4) | 3,232 (19.7) | |

| 2004-2006 | 22,816 (20.8) | 16,520 (20.1) | 2,550 (22.7) | 3,746 (22.8) | |

| 2007-2009 | 25,289 (23.0) | 18,032 (22.0) | 3,010 (26.7) | 4,247 (25.9) | |

| Stage | |||||

| In situ | 18,337 (16.7) | 13,847 (16.9) | 2,033 (18.1) | 2,457 (15.0) | <.0001 |

| Local | 57,599 (52.5) | 44,873 (54.7) | 4,847 (43.1) | 7,879 (48.0) | |

| Regional | 28,318 (25.8) | 19,749 (24.1) | 3,427 (30.5) | 5,142 (31.3) | |

| Distant | 5,495 (5.0) | 3,620 (4.4) | 946 (8.4) | 929 (5.7) | |

| Grade | |||||

| Low | 56,019 (51.0) | 43,842 (53.4) | 4,721 (42.0) | 7,456 (45.4) | <.0001 |

| High | 35,327 (32.2) | 24,604 (30.0) | 4,650 (41.3) | 6,073 (37.0) | |

| Unknown | 18,403 (16.8) | 13,643 (16.6) | 1,882 (16.7) | 2,878 (17.5) | |

| Histology | |||||

| Ductal | 75,944 (69.2) | 56,651 (69.0) | 7,927 (70.4) | 11,366 (69.3) | <.0001 |

| Lobular | 9,032 (8.2) | 7,119 (8.7) | 726 (6.5) | 1,187 (7.2) | |

| Other | 24,196 (22.0) | 17,932 (21.8) | 2,508 (22.3) | 3,756 (22.9) | |

| Unknown | 577 (0.5) | 387 (0.5) | 92 (0.8) | 98 (0.6) | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p (anova) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 65.34 (10.48) | 65.84 (10.57) | 64.01 (10.29) | 63.75 (9.95) | <.0001 |

| Mammography Capacity | 10.07 (5.29) | 10.13 (5.60) | 10.74 (4.75) | 9.31 (3.73) | <.0001 |

| Census Tract Poverty (%) | 12.73 (10.6) | 9.93 (7.91) | 20.83 (12.69) | 21.17 (13.1) | <.0001 |

The distribution of and correlations between segregation variables are provided by patient race/ethnicity in Table 2. Compared to Whites, Blacks and Hispanics lived in more segregated neighborhoods. Average Black segregation (Black LQ=3.29) experienced by Blacks was ~2.5 times higher than average Hispanic segregation experienced by Hispanics (Hispanic LQ=1.27). Correlations between Black and Hispanic LQ were modest. The correlation between Black and Hispanic segregation was positive among Whites (ρ= .290, p<.0001). In other words, Whites living in neighborhoods with greater Black segregation also experienced greater Hispanic segregation. However, the correlation was negative among Blacks (ρ= −.342, p<.0001) and Hispanics (ρ= −.104, p<.0001).

Table 2.

Distribution and Spearman Correlation Coefficient (ρ) of Black and Hispanic Segregation Variables by Patient Race/ethnicity for Breast Cancer Patients (n=109,749) Diagnosed in Texas, 1995-2009

| Black segregation (LQ) | Hispanic segregation (LQ) | Correlation | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Median | Interquartile Range | % ≥1 | Mean | SD | Median | Interquartile Range | % ≥1 | ρ | |

| White (n=82,089) | 0.63*** | 0.89 | 0.35 | 0.12-0.78 | 18.22 | 0.73 *** | 0.63 | 0.54 | 0.30-0.92 | 22.10 | 0.450*** |

| Black (n=11,253) | 3.29 | 2.39 | 3.09 | 1.16-5.21 | 78.00 | 0.90 | 0.78 | 0.63 | 0.35-1.19 | 33.00 | −0.342*** |

| Hispanic (n=16,407) | 0.87 | 1.39 | 0.43 | 0.09-1.09 | 27.52 | 1.27 | 0.74 | 1.11 | 0.82-1.61 | 61.77 | −0.104*** |

| Total | 0.94 | 1.45 | 0.42 | 0.14-1.03 | 25.74 | 0.83 | 0.69 | 0.63 | 0.34-1.09 | 29.15 | 0.290*** |

p<.0001 Overall range of LQ was 0-19.80.

LQ = location quotient for residential racial segregation.

For the remaining proportional hazard model analyses, LQ has been log-transformed. This transformation affects how the hazard ratio (HR) is interpreted. The HR can be interpreted as representing the change in the risk of death if LQ rises by one log-unit. In turn, every LQ log-unit increase represents a ten-fold change in the LQ+1. For example, every log-unit increase of Hispanic LQ is associated with an adjusted HR of 1.24 in cause-specific death (Table 3, Model 2). This log-unit change corresponds to a change in the LQ from 0 to 10, or 1 to 20.

Table 3.

Hazard Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals for the Association of Residential Segregation with Cause-Specific and All-Cause Mortality among Breast Cancer Patients (n=109,749) Diagnosed in Texas, 1995-2009

| Cause-Specific Mortality | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Univariate Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| HR (95% CI) | aHR (95% CI) | aHR (95% CI) | |

| Segregation | |||

| Black LQa | 2.13 (1.94-2.35) | 1.06 (0.95-1.18) | - |

| Hispanic LQa | 2.64 (2.26-3.09) | 1.24 (1.05-1.46) | - |

| Patient Race/ethnicity | |||

| Black (vs. white) | 2.14 (2.02-2.26) | 1.46 (1.36-1.56) | 1.47 (1.38-1.56) |

| Hispanic (vs. white) | 1.39 (1.32-1.47) | 1.03 (0.96-1.09) | 1.03 (0.97-1.10) |

| All-Cause Mortality | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Univariate Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| HR (95% CI) | aHR (95% CI) | aHR (95% CI) | |

| Segregation | |||

| Black LQa | 1.66 (1.56-1.77) | 1.07 (1.00-1.15) | - |

| Hispanic LQa | 2.52 (2.29-2.77) | 1.44 (1.30-1.59) | - |

| Patient Race/ethnicity | |||

| Black (vs. white) | 1.39 (1.34-1.45) | 1.31 (1.26-1.37) | 1.32 (1.27-1.37) |

| Hispanic (vs. white) | 0.95 (0.92-0.98) | 0.93 (0.90-0.97) | 0.94 (0.91-0.98) |

Per log unit increase

LQ was transformed via log(x+1). Bold text indicates p<.05. Model 1 presents univariate hazard ratios; Models 2 and 3 include patient race/ethnicity as well as age, sex, tumor grade, tumor stage, year of diagnosis, tumor histology, census tract poverty, and number of mammography facilities per 100,000 women aged ≥50 years. Model 2 additionally includes segregation variables. Dashes (-) indicate that the variables were not entered into the model.

LQ = location quotient for residential racial segregation. HR = hazard ratio. aHR = adjusted hazard ratio. CI = confidence interval.

Question 1, Is segregation adversely associated with mortality?

Cause-Specific Mortality

Individuals living in a neighborhood with a higher proportion of Blacks relative to the MSA (i.e., higher Black LQ) were more likely to die of breast cancer than patients living in a less segregated neighborhood in univariate analysis (Table 3, Unadjusted Model 1). In the fully adjusted model (Table 3, Model 2) higher Hispanic (aHR: 1.24; 95% CI: 1.05-1.46) but not Black (aHR: 1.06; 95% CI: 0.95-1.18) segregation was associated with higher cause-specific mortality.

All-Cause Mortality

We found a similar pattern for all-cause mortality wherein greater segregation was associated with higher all-cause mortality amongst all patients of any race/ethnicity. In univariate analysis, both higher Black (HR: 1.66; 95% CI: 1.56-1.77) and Hispanic (HR: 2.52; 95% CI: 2.29-2.77) segregation was associated with higher all-cause mortality (Table 3, Unadjusted Model 1). In the fully adjusted model (Table 3, Model 2) higher Black (aHR: 1.07; 95% CI: 1.00-1.15) (p=.04) and Hispanic (aHR: 1.44; 95% CI: 1.30-1.59) segregation remained associated with higher all-cause mortality.

Question 2, To what extent does segregation explain racial/ethnic disparities in mortality?

To answer this question, we examined how the main effect of patient race/ethnicity changed between the fully adjusted model (Table 3, Model 2) and the same model without segregation (Table 3, Model 3).

Cause-Specific Mortality

Blacks, compared to whites, were more than twice as likely to die from breast cancer (Table 3, Univariate Model 1-- HR: 2.14; 95% CI: 2.02-2.26). This association was attenuated after adjustment for all covariates (Table 3, Model 2-- aHR: 1.46; 95% CI: 1.36-1.56) but was virtually unchanged between Models 2 and 3 after dropping segregation from the fully adjusted model.

Similarly, in univariate analysis, Hispanics, compared to Whites, were more likely to die from breast cancer (Table 3, Univariate Model 1-- HR: 1.39; 95% CI: 1.32-1.47). This Hispanic disparity was completely attenuated (Table 3, Model 2-- aHR: 1.03, 95% CI: 0.96-1.09) after adjusting for covariates in the fully adjusted model and remained virtually unchanged after dropping segregation from the model (Table 3, Model 3).

All-Cause Mortality

Blacks, compared to whites, were more likely to die from all causes in both univariate (Table 3, Univariate Model 1-- HR: 1.39; 95% CI: 1.34-1.45) and fully adjusted models (Table 3, Model 2—aHR: 1.31; 95% CI: 1.26-1.37). The Black disadvantage persisted and was virtually unchanged with and without adjustment for segregation in Models 2 and 3.

Hispanics, compared to whites, were less likely to die from all-causes in both unadjusted (Table 3, Univariate Model 1-- HR: 0.95 95% CI: 0.92-0.98) and fully adjusted models (Table 3, Model 2-- aHR: 0.93; 95% CI: 0.90-0.97). This Hispanic advantage persisted and was virtually unchanged after dropping segregation from the model in Model 3.

Collectively, the lack of change in parameter estimates suggests that segregation, in isolation of other model covariates such as neighborhood poverty, does not explain observed racial/ethnic disparities in mortality.

Question 3, Does Patient Race/Ethnicity Moderate the Association between Segregation and Mortality?

Comparing a series of interaction models [data not shown] to Model 2, we found statistically significant effect moderation of race/ethnicity and LQ (likelihood ratio test p<.05) for all-cause and cause-specific mortality. When assessed in stratified analysis, we found a mixed pattern of associations between segregation and mortality by patient race/ethnicity.

Cause-Specific Mortality

Stratified univariate analyses (Table 4, Model 4) demonstrated that greater segregation was significantly associated with higher cause-specific mortality. Whites were more likely to die of breast cancer if they lived in neighborhoods with more Blacks or Hispanics relative to the surrounding MSA. Blacks had higher cause-specific mortality if they lived in neighborhoods with more Blacks (but not Hispanics) relative to the surrounding MSA. Hispanics had higher cause-specific mortality if they lived in neighborhoods with more Hispanics (but not Blacks) relative to the surrounding MSA. In the multivariable model (Table 4, Model 5), greater Hispanic segregation remained significantly associated with higher mortality only among Whites.

Table 4.

Patient Race/Ethnicity-Specific Hazard Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals for the Association of Residential Segregation (LQ) with Cause-Specific and All-Cause Mortality among Breast Cancer Patients (n=109,749) Diagnosed in Texas, 1995-2009

| Cause-Specific Mortality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Univariate Model 4 HR (95% CI) |

Model 5 aHR (95% CI) |

|||||

| White (n=82,089) | Black (n=11,253) | Hispanic (n=16,407) | White (n=82,089) | Black (n=11,253) | Hispanic (n=16,407) | |

| Black LQa | 1.41 (1.20-1.66) | 1.21 (1.01-1.46) | 0.90 (0.71-1.14) | 1.02 (0.87-1.20) | 0.99 (0.80-1.24) | - |

| Hispanic LQa | 2.63 (2.19-3.16) | 1.15 (0.84-1.59) | 2.13 (1.47-3.09) | 1.44 (1.14-1.82) | - | 1.25 (0.82-1.90) |

| All-Cause Mortality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Univariate Model 4 HRa (95% CI) |

Model 5 aHRa (95% CI) |

|||||

| White (n=82,089) | Black (n=11,253) | Hispanic (n=16,407) | White (n=82,089) | Black (n=11,253) | Hispanic (n=16,407) | |

| Black LQa | 1.56 (1.43-1.71) | 1.25 (1.10-1.42) | 0.96 (0.83-1.10) | 1.11 (1.02-1.21) | 0.91 (0.77-1.08) | - |

| Hispanic LQa | 3.40 (3.05-3.80) | 1.45 (1.16-1.81) | 1.76 (1.41-2.19) | 1.46 (1.29-1.66) | 1.12 (0.88-1.43) | 1.03 (0.80-1.33) |

Per log unit increase

LQ was transformed via log(x+1). Bold text indicates p<.05. Model 4 presents univariate hazard ratios; Model 5 adjusts for patient age, sex, tumor grade, tumor stage, year of diagnosis, tumor histology, census tract poverty, and number of mammography facilities per 100,000 women aged ≥50 years. Dashes (-) indicate that the variable was not entered into the multivariable model due to p≥.05 in the univariate model. LQ = location quotient for residential racial segregation. HR = hazard ratio. aHR = adjusted hazard ratio. CI = confidence interval.

All-Cause Mortality

In stratified univariate analyses (Table 4, Model 4), both Black and Hispanic LQ were positively associated with all-cause mortality for Whites and Blacks such that greater Black and Hispanic segregation were associated with higher all-cause mortality. Among Hispanics, only Hispanic segregation was significant; greater Hispanic segregation was associated with higher all-cause mortality among Hispanics. In the multivariable model (Table 4, Model 5), greater Hispanic and Black segregation remained significantly associated with higher mortality only among Whites.

DISCUSSION

Results suggest that living in a neighborhood with a higher proportion of racial and ethnic minorities relative to the surrounding MSA (i.e., Black and Hispanic segregation) is adversely associated with mortality (Question 1); does not fully explain the main effect of race/ethnicity on mortality after adjusting for other tumor, patient, and neighborhood covariates (Question 2); and the negative effects of segregation may differ by patient race/ethnicity (Question 3).

Among women of all racial/ethnic groups, greater segregation was adversely associated with both outcomes. The adverse association of segregation persisted after including race/ethnicity and other prognostic factors in the model. This finding confirms a robust literature suggesting adverse effects of segregation on health outcomes in the U.S.13,15-17

We confirmed racial/ethnic disparities in mortality (as expected). Specifically, we demonstrated that Black women faced a higher mortality risk, compared to whites, for both outcomes. This finding confirms a significant body of existing research that finds a persistent Black disparity in mortality among breast cancer patients.1,5,29 After adjustment for tumor, patient, and neighborhood level covariates, segregation did not explain the observed Black disparities in mortality. In prior studies, segregation explained some of the Black-White disparity in breast cancer care but not mortality in one study8 while another concluded that segregation did not explain disparities in either stage or survival7. Together these results suggest that while an important correlate of survival, residential segregation by itself does not fully explain the strong and persistent survival disadvantage experienced by Black women with cancer.

Findings regarding Hispanics were more mixed. While Hispanics were more likely (in unadjusted models) or equally likely (in adjusted models) as Whites to die from breast cancer, they were less likely to die than Whites from all-causes across both models. This latter finding is consistent with the general notion of a Hispanic mortality paradox—the epidemiologic phenomenon where Hispanics tend to live longer than non-Hispanic whites, despite having a worse risk factor profile30. We found that, after adjusting for covariates, segregation did not account for the observed Hispanic advantage in all-cause mortality. Whether advantageous or disadvantageous, persistent and unexplained racial/ethnic differences in cancer mortality, as seen here, should remain a national research priority.31-34

Our results suggest that in the presence of other explanatory variables and covariates, the additional inclusion of segregation into analytic models is unlikely to substantially alter the main effects—whether detrimental or advantageous—of race/ethnicity on mortality. There are several possible explanations for this finding that may reflect our analytic choices. As one example, we examined whether segregation explained racial/ethnic disparities in mortality in models adjusting for numerous other covariates, including neighborhood poverty. If segregation is a fundamental cause of spatial poverty concentration,23 poverty is a mediator and thus adjusting for poverty effectively captures much of the segregation effect. In this scenario, the inclusion and removal of segregation in models 2 and 3 may have limited impact on the main effect of race/ethnicity on mortality. Our choices reflect our conceptual model although given the complex causal pathways between the variables studied here, poverty could also be hypothesized as a confounder of the segregation and mortality relationship. Clearly, given the recent revived interest35-39 in causal inferences related to race in regressions adjusting for confounding and mediating variables, additional studies are warranted to better understand—both conceptually and analytically—the complex inter-relationships between race/ethnicity, neighborhood poverty, neighborhood segregation, and mortality.

Differential Effect of Segregation by Patient Race/ethnicity

Associations varied when examined separately by patient race/ethnicity such that segregation was either not significantly associated with or was adversely associated with mortality. Notably, in stratified multivariable models, segregation measures were negatively associated with mortality among Whites; no segregation measures were associated with mortality among Blacks or Hispanics. These findings add to a nascent but growing literature suggesting differential effects of segregation.6,7,13,17 For example, among breast cancer patients in California, living in neighborhoods with higher proportions of Black residents was associated with increased mortality among whites but decreased mortality among Blacks.7

Unlike other studies,7,13,17 we observed no evidence of a protective effect of segregation among any racial/ethnic group.7,13,17 Two studies focused on cancer outcomes found that Hispanics may experience a survival advantage, particularly those living in more ethnically dense neighborhoods.11,40 The protective effects of living in areas with high racial/ethnic minority composition have been referred to as barrio effects and are thought to reflect sociocultural advantages rather than socioeconomic disadvantages.10 To date, the role of barrio effects or ethnic enclaves (a related construct)on breast cancer outcomes has not been widely studied.9 In fact, given different historical, political, and social contexts, “segregation” as such may not be the most relevant construct among Hispanic populations. Ethnic density or ethnic enclaves may be more appropriate for measuring protective effects of neighborhood race/ethnicity. More attention should be paid toward the definition and application of these various constructs, recognizing the value-laden labels and the extent to which they may constrain our thinking about conceptual models and relevant hypotheses.

Measuring Black and Hispanic Segregation using the LQ

To our knowledge, ours is the first study to measure both Hispanic and Black segregation using the LQ. Thus, it is important to consider our findings regarding Hispanic and Black segregation in light of the unique properties of the LQ measure. First, we demonstrated that the mean Black LQ experienced by Blacks was ~2.5 times higher than the average Hispanic LQ experienced by Hispanics. This finding confirms decades of research demonstrating that Blacks face the highest degree of segregation of any U.S. racial/ethnic group.41

Second, across adjusted models, Hispanic segregation was more consistently associated with mortality than Black segregation. Black segregation only remained significant in two adjusted models. However, it's difficult to draw definitive conclusions about these findings. As a relative measure, the possible range of LQ is dependent on the racial/ethnic composition of the surrounding MSA. Thus, the Black and Hispanic LQ may not be able to take the same values mathematically. While we sought to attenuate this concern by modeling the effects of log-transformed LQ, caution is advised when comparing the effects of Black vs. Hispanic LQ, or the effect of LQs across models.

Third, we described significant correlations between Black LQ and Hispanic LQ, such that disentangling the independent effects of either is not possible given our data. Indeed, because segregation results from complex historical and ongoing processes involving economic, legal, political, social, and spatial interrelationships between residents of multiple races, these measures may not have truly independent effects. The LQ is a newly introduced small-area measure of segregation. The extent to which LQ is comparable to, or different from, large-area measures (e.g. dissimilarity index), deserves further study. Exploring a variety of measures might serve to broaden our thinking about conceptual models and relevant hypotheses. For example, MSA-level segregation measures may capture housing choice restriction while small-area measures may reflect daily, lived experiences of residents (e.g. perceived discrimination). These mechanisms might differentially influence health outcomes in unexplored ways. Mixed methods study designs will be useful for the identification of potential mechanisms, particularly those at the local, small-area level.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study is subject to limitations. TCR lacked data on several treatment and prognostic factors so we could not adjust for these factors. TCR also does not capture life-course measures of segregation such as residential address history and length of neighborhood residence. Thus, by measuring neighborhood residence and neighborhood segregation at a single point in time (i.e. at cancer diagnosis only), and not utilizing a life-course perspective that captures cumulative exposures and susceptibilities across a patients’ life,42 we may have underestimated the cumulative effects of segregation on mortality. The LQ is an “aspatial” segregation measure limited by the use of census tract boundaries, thus it cannot account for the segregation of adjacent census tracts. The LQ also cannot account for the complexities of segregation patterns across multiple racial groups and may not be directly comparable across models. More investment should be made in the development of small-area spatial measures capable of measuring multi-group segregation. Finally, results may not be generalizable to patients living outside of Texas who may differ in unknown ways.

Our study also has numerous strengths. We present some of the first research examining the role of segregation on cancer outcomes among a tri-ethnic sample of Blacks, Hispanics, and Whites. We apply a frailty model, accounting for the hierarchical clustering of patients. We also provide the first application of the LQ measure in the cancer literature. In doing so, we contribute to findings from the first published use of this measure that demonstrated an adverse longitudinal impact of LQ on major health declines and death.15 The LQ offers several advantages over existing measures, namely that it measures small-area relative segregation, thus capturing local-area contexts experienced by residents and quantifying racial/ethnic dispersion. Further, LQ is easy to calculate and understand and requires no specialized software, and thus has potential for wider application and replication across the health literature.

Conclusions

Overall, we found that segregation is adversely associated with mortality among breast cancer patients, does not explain persistent racial/ethnic disparities in mortality after adjustment for tumor, patient, and neighborhood covariates, and that its effects may differ by patient race/ethnicity. Further research is needed to more rigorously distinguish the complex relationships of segregation, patient race/ethnicity and cancer outcomes. Understanding mechanisms underlying these relationships will facilitate identification of potential health system, policy, or individual interventions designed to ameliorate the adverse effects of segregation. Finally, a thoughtful review of the literature on racial/ethnic enclaves versus segregation would guide future research by clarifying conceptual and operational definitions as well as how those constructs hypothetically impact health outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT R1208), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R24 HS 22418-01), and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, UT Southwestern Center for Translational Medicine (U54 RFA-TR-12-006). Contents of this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of funding agencies. Cancer data have been provided by the Texas Cancer Registry, Cancer Epidemiology and Surveillance Branch, Texas Department of State Health Services, 211 E. 7th Street, Suite 325, Austin, TX 78701, http://www.dshs.state.tx.us/tcr/default.shtm, or (512) 305-8506. We thank E Scott Morris for assistance with Census data.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012 Jan-Feb;62(1):10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Massey DS, Denton NA. The Dimensions of Residential Segregation. Social Forces. 1988;67(2):281–315. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public health reports. 2001 Sep-Oct;116(5):404–416. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.5.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dai D. Black residential segregation, disparities in spatial access to health care facilities, and late-stage breast cancer diagnosis in metropolitan Detroit. Health Place. 2010 Sep;16(5):1038–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Russell E, Kramer MR, Cooper HL, Thompson WW, Arriola KR. Residential racial composition, spatial access to care, and breast cancer mortality among women in Georgia. J Urban Health. 2011 Dec;88(6):1117–1129. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9612-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Russell EF, Kramer MR, Cooper HL, Gabram-Mendola S, Senior-Crosby D, Jacob Arriola KR. Metropolitan area racial residential segregation, neighborhood racial composition, and breast cancer mortality. Cancer Causes Control. 2012 Sep;23(9):1519–1527. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-0029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warner ET, Gomez SL. Impact of neighborhood racial composition and metropolitan residential segregation on disparities in breast cancer stage at diagnosis and survival between black and white women in California. Journal of community health. 2010 Aug;35(4):398–408. doi: 10.1007/s10900-010-9265-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haas JS, Earle CC, Orav JE, et al. Racial segregation and disparities in breast cancer care and mortality. Cancer. 2008 Oct 15;113(8):2166–2172. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keegan TH, Quach T, Shema S, Glaser SL, Gomez SL. The influence of nativity and neighborhoods on breast cancer stage at diagnosis and survival among California Hispanic women. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:603. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eschbach K, Ostir GV, Patel KV, Markides KS, Goodwin JS. Neighborhood context and mortality among older Mexican Americans: is there a barrio advantage? Am J Public Health. 2004 Oct;94(10):1807–1812. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.10.1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel MI, Schupp CW, Gomez SL, Chang ET, Wakelee HA. How do social factors explain outcomes in non-small-cell lung cancer among Hispanics in California? Explaining the Hispanic paradox. J Clin Oncol. 2013 Oct 1;31(28):3572–3578. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.6217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaw RJ, Pickett KE, Wilkinson RG. Ethnic density effects on birth outcomes and maternal smoking during pregnancy in the US linked birth and infant death data set. Am J Public Health. 2010 Apr;100(4):707–713. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.167114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.White K, Borrell LN. Racial/ethnic residential segregation: framing the context of health risk and health disparities. Health Place. 2011 Mar;17(2):438–448. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.James DR, Taeuber KE. Measures of Segregation. In: Tuma Nancy., editor. Sociological Methodology. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 1985. pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sudano JJ, Perzynski A, Wong DW, Colabianchi N, Litaker D. Neighborhood racial residential segregation and changes in health or death among older adults. Health Place. 2013 Jan;19:80–88. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White K, Haas JS, Williams DR. Elucidating the role of place in health care disparities: the example of racial/ethnic residential segregation. Health services research. 2012 Jun;47(3 Pt 2):1278–1299. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01410.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kramer MR, Hogue CR. Is segregation bad for your health? Epidemiol Rev. 2009;31:178–194. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxp001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landrine H, Corral I. Separate and unequal: residential segregation and black health disparities. Ethn Dis. 2009;19(2):179–184. Spring. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerend MA, Pai M. Social determinants of Black-White disparities in breast cancer mortality: a review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008 Nov;17(11):2913–2923. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maskarinec G, Sen C, Koga K, Conroy SM. Ethnic differences in breast cancer survival: status and determinants. Womens Health (Lond Engl) 2011 Nov;7(6):677–687. doi: 10.2217/whe.11.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haas JS, Earle CC, Orav JE, Brawarsky P, Neville BA, Williams DR. Racial segregation and disparities in cancer stage for seniors. J Gen Intern Med. 2008 May;23(5):699–705. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0545-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaskin DJ, Dinwiddie GY, Chan KS, McCleary RR. Residential segregation and the availability of primary care physicians. Health services research. 2012 Dec;47(6):2353–2376. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01417.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Massey DS, Fischer MJ. How segregation concentrates poverty. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2000;23(4) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bartlett MS. The use of transformations. Biometrics. 1947 Mar;3(1):39–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lachin JM, McGee PL, Greenbaum CJ, et al. Sample size requirements for studies of treatment effects on beta-cell function in newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e26471. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, May S. Applied survival analysis: Regression modeling of time to event data. 2nd edition Wiley-Interscience; Hoboken, New Jersey: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Team RD. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: [11-3-13]. from http://www.R-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Snijders TAB, Bosker R. Multilevel analysis. An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Field TS, Buist DS, Doubeni C, et al. Disparities and survival among breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2005;(35):88–95. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgi044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruiz JM, Steffen P, Smith TB. Hispanic mortality paradox: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the longitudinal literature. Am J Public Health. 2013 Mar;103(3):e52–60. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Committee on Understanding Eliminating Racial Ethnic Disparities in Health Care . Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in Health Care. The National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Institute of Medicine . How far have we come in reducing health disparities?: Progress since 2000: Workshop summary. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Institute of Medicine . State and Local Policy Initiatives to Reduce Health Disparities: Workshop Summary. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shi L, Lebrun LA, Zhu J, Tsai J. Cancer screening among racial/ethnic and insurance groups in the United States: a comparison of disparities in 2000 and 2008. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved. 2011 Aug;22(3):945–961. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.VanderWeele TJ, Robinson WR. The authors respond. Epidemiology. 2014 Nov;25(6):937–938. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.VanderWeele TJ, Robinson WR. Rejoinder: how to reduce racial disparities?: Upon what to intervene? Epidemiology. 2014 Jul;25(4):491–493. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.VanderWeele TJ, Robinson WR. On the causal interpretation of race in regressions adjusting for confounding and mediating variables. Epidemiology. 2014 Jul;25(4):473–484. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Glymour C, Glymour MR. Commentary: race and sex are causes. Epidemiology. 2014 Jul;25(4):488–490. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krieger N. On the causal interpretation of race. Epidemiology. 2014 Nov;25(6):937. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schupp CW, Press DJ, Gomez SL. Immigration factors and prostate cancer survival among Hispanic men in California: Does neighborhood matter? Cancer. 2014 Jan 29; doi: 10.1002/cncr.28587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Massey DS, Denton NA. American Apartheid. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Osypuk TL. Invited commentary: integrating a life-course perspective and social theory to advance research on residential segregation and health. Am J Epidemiol. 2013 Feb 15;177(4):310–315. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]