LCuOTf complexes (L = CAACs or NHCs) selectively promote the dehydrogenative borylation of C(sp)–H bonds at room temperature.

LCuOTf complexes (L = CAACs or NHCs) selectively promote the dehydrogenative borylation of C(sp)–H bonds at room temperature.

Abstract

LCuOTf complexes [L = cyclic (alkyl)(amino)carbenes (CAACs) or N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs)] selectively promote the dehydrogenative borylation of C(sp)–H bonds at room temperature. It is shown that σ,π-bis(copper) acetylide and copper hydride complexes are the key catalytic species.

Popularized by the Suzuki–Miyaura reaction, organoboronic esters and acids are now regarded as key building blocks for compounds with applications ranging from material to life sciences. Consequently, numerous methodologies have been developed to access these valuable substrates.1 Following ground-breaking reports by Hartwig et al.,2 and Smith et al.,3 the catalytic dehydrogenative borylation of C(sp3)–H bonds and C(sp2)–H bonds are now well documented.4 In contrast, for C(sp)–H bonds there are only a few reports by Ozerov et al. 5 using iridium and palladium complexes supported by pincer ligands, and one by Tsuchimoto et al. 6 with zinc triflate, which is only effective with 1,8-naphthalenediaminatoborane as the boron partner. One of the difficulties of the dehydrogenative borylation of terminal alkynes is the competing hydroboration of the triple bond, which affords alkenyl boronic esters.7

We recently reported8 on the role of the X ligand in the mechanism of the LCuX catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC reaction) [L = cyclic (alkyl)(amino)carbene].9,10 Herein we show that these results allow for the rational design of copper catalysts that selectively promote the dehydrogenative borylation of terminal alkynes with pinacolborane.

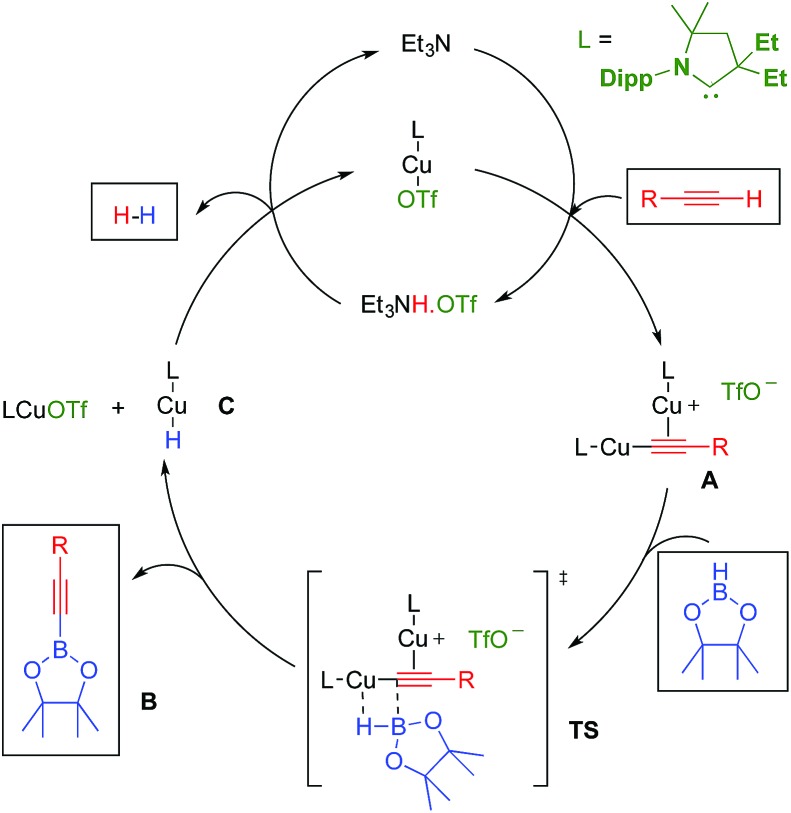

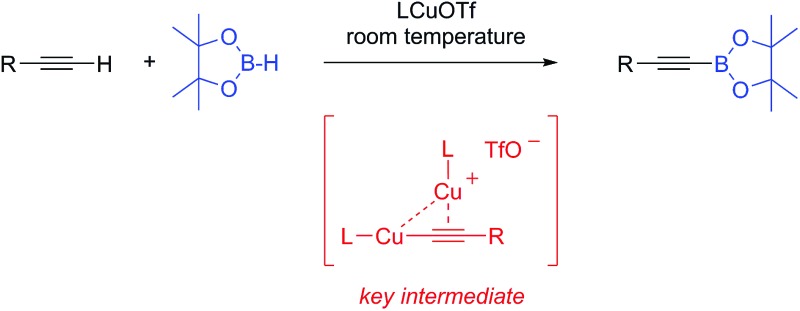

In the above mentioned study, we found that in the presence of triethylamine, LCuOTf reacts with terminal alkynes to give the catalytically active σ,π-bis(copper) acetylides A,8,11 along with ammonium triflate (Scheme 1). We hypothesized that in dinuclear complexes A, the triple bond is protected which should prevent the classical hydroboration reaction leading to alkenyl boronic esters. Instead, the highly polarized copper–carbon bond could undergo a σ-bond metathesis with pinacolborane (TS) to afford the desired alkynyl boronic ester B, as well as the copper hydride C. The latter should react with triethylammonium triflate to regenerate LCuOTf and triethylamine with the elimination of dihydrogen.

Scheme 1. Hypothetical mechanism for the LCuOTf induced dehydrogenative borylation of terminal alkynes.

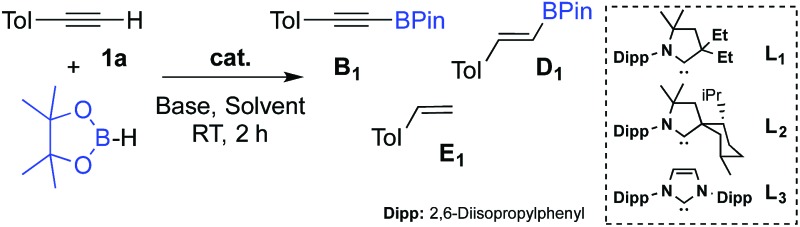

We first checked that in the absence of catalyst no reaction occurred between p-tolylacetylene 1a and pinacolborane in C6D6 at room temperature for 2 hours (Table 1, entry 1). In the presence of 1 mol% of L1CuOTf, no significant reaction occurred either because of the difficulty of the triflate to deprotonate the alkyne8 (entry 2). In order to promote the deprotonation of the alkyne, 1 mol% of Et3N was added which resulted in immediate hydrogen evolution (as characterized by a singlet at 4.47 ppm in 1H NMR). The major product was the alkynyl boronic ester B1 (48%), but the alkenyl boronic ester D1 (11%), and the styrene derivative E1 (7%) were also formed (entry 3).

Table 1. Optimization of the dehydrogenative borylation reaction a .

| ||||||||

| Entry | Cat. (mol%) | Base (mol%) | Solvent | Conc. (M) | 1a b (%) | B1 b (%) | D1 b (%) | E1 b (%) |

| 1 | — | — | C6D6 | 1.4 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | L1CuOTf (1) | — | C6D6 | 1.4 | 86 | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| 3 | L1CuOTf (1) | Et3N (1) | C6D6 | 1.4 | 14 | 48 | 11 | 7 |

| 4 | CuOTf | Et3N (1) | C6D6 | 1.4 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | L1CuOTf (1) | Et3N (2) | C6D6 | 1.4 | 1 | 70 | 14 | 12 |

| 6 | L1CuOTf (1) | Et3N (2) | CD2Cl2 | 1.4 | 12 | 42 | 6 | 26 |

| 7 | L1CuOTf (1) | Et3N (2) | THF-d8 | 1.4 | 5 | 64 | 12 | 17 |

| 8 | L1CuOTf (1) | Et3N (2) | CD3CN | 1.4 | 18 | 38 | 0 | 6 |

| 9 | L1CuOTf (1) | iPrNH2 (2) | C6D6 | 1.4 | 67 | 5 | 12 | 10 |

| 10 | L1CuOTf (1) | iPr2NH (2) | C6D6 | 1.4 | 47 | 11 | 13 | 7 |

| 11 | L1CuOTf (1) | iPr2NEt (2) | C6D6 | 1.4 | 10 | 28 | 45 | 3 |

| 12 | L1CuOTf (1) | BnNEt2 (2) | C6D6 | 1.4 | 14 | 53 | 8 | 7 |

| 13 | L1CuOTf (1) | DABCO (2) | C6D6 | 1.4 | 18 | 60 | 1 | 7 |

| 14 | L1CuOTf (0.25) | Et3N (0.5) | C6D6 | 1.4 | 37 | 36 | 15 | 6 |

| 15 | L1CuOTf (0.5) | Et3N (1) | C6D6 | 1.4 | 20 | 54 | 15 | 9 |

| 16 | L1CuOTf (2.5) | Et3N (5) | C6D6 | 1.4 | 4 | 83 | 4 | 7 |

| 17 | L 1 CuOTf (2.5) | Et 3 N (5) | C 6 D 6 | 0.1 | 1 | 98 | 0 | 1 |

| 18 | L2CuOTf (2.5) | Et3N (5) | C6D6 | 0.1 | 0 | 96 | 0 | 4 |

| 19 | L3CuOTf (2.5) | Et3N (5) | C6D6 | 0.1 | 0 | 92 | 0 | 8 |

aReactions were carried out in a test tube for 2 h at RT under an argon atmosphere using a 1 : 1 mixture (0.69 mmol) of p-tolylacetylene and pinacolborane.

bMeasured by NMR using 1,4-dioxane as an internal standard.

Note that no reaction occurred under ligand-free conditions (entry 4). Encouraged by these preliminary results, we further optimized the dehydrogenative borylation leading to B1. We found that a two-fold excess of Et3N with respect to (CAAC) CuOTf was beneficial (entry 5). By screening solvents (Entries 5–8) and base additives (Entries 9–13), we identified benzene and Et3N as being most appropriate for the reaction. When we increased the catalyst loading to 2.5 mol% (Entries 14–16), and decreased the concentration of the solution from 1.4 to 0.1 mol L–1 (entry 17) there was quantitative formation of the desired alkynyl boronic ester B1 with excellent selectivity within two hours at room temperature. Notably, substitution of ligand L1 for the more bulky menthyl CAAC L2 or even IPr-NHC12 L3 gave comparable results.

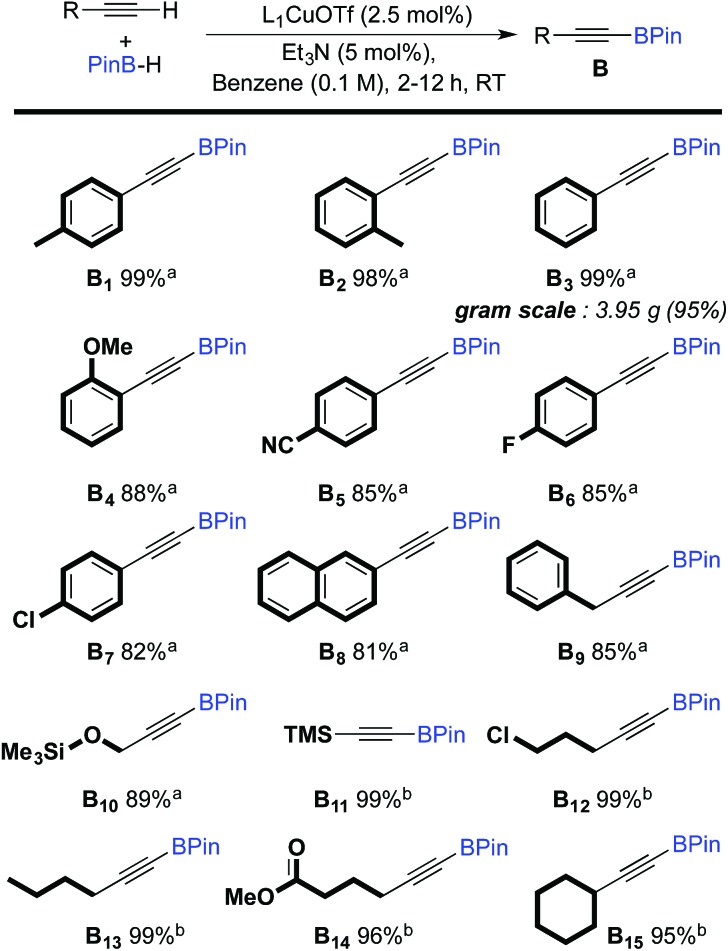

The scope of the dehydrogenative borylation reaction was then studied at room temperature in a benzene solution (0.1 M) using a stoichiometric mixture of alkyne and borane (1.82 mmol), 5 mol% of Et3N and 2.5 mol% of L1CuOTf (Scheme 2). This methodology is readily applicable to a broad range of terminal alkynes bearing functionalities such as OMe, CN, F, Cl, TMS and CO2Me. It is worth noting that electron-rich terminal alkynes require longer reaction times (12 h instead of 2 h) (B11–15). Alkynyl boronic esters B1–15 were isolated in good to excellent yields via filtration through a short plug of dry neutral alumina using pentane as the eluent. This straightforward protocol allows for gram-scale synthesis, as shown for B3.

Scheme 2. Scope of the dehydrogenative borylation of terminal alkynes. [a] Reaction time 2 h. [b] Reaction time 12 h.

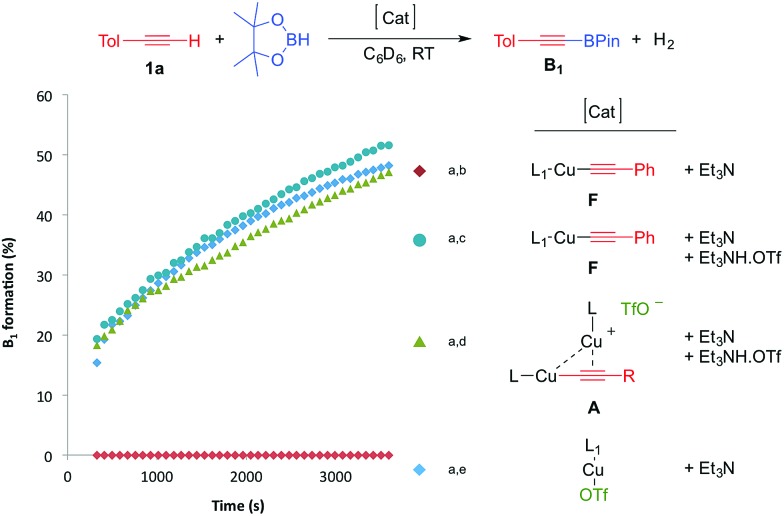

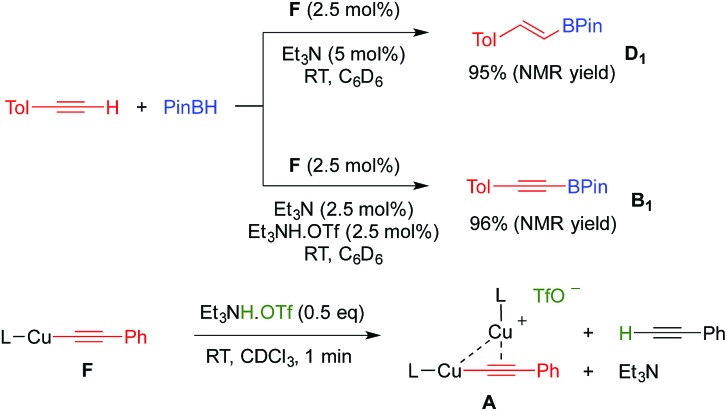

With these results in hand, we performed a set of experiments in order to verify our mechanistic hypothesis. When the 2.5 mol% mononuclear complex F was used, with or without Et3N, no traces of the dehydrogenative borylation product B1 were observed, instead the hydroboration product D1 was quantitatively formed (Fig. 1 and Scheme 3) (see also the kinetic profile in the ESI†). In marked contrast, when 2.5 mol% Et3NH·OTf was added as a proton source, we observed the rapid formation of B1, and the kinetic profile was comparable with those obtained using our standard catalytic conditions (LCuOTf/Et3N) or the bis(copper) acetylide A. Since we already proved that LCuOTf/Et3N reacts with terminal alkynes to afford the dinuclear species A,8 we verified that similarly complex F reacts with Et3NH·OTf to give A. These experiments as a whole strongly suggest that the dinuclear complex A is pivotal in the dehydrogenative process.

Fig. 1. Kinetic profiles of the formation of B1 using various catalytic systems. [a] Reactions were carried out in a J-Young NMR tube at RT under an argon atmosphere using a 1 : 1 mixture (0.45 mmol) of p-tolylacetylene and pinacolborane in 1 mL of C6D6. [b] 2.5 mol% of F and 5 mol% Et3N; no trace of B1 was observed, instead D1 was obtained quantitatively. [c] 2.5 mol% of F, Et3N and Et3NH·OTf. [d] 2.5 mol% of A, 3.75 mol% Et3N and 1.25 mol% Et3NH·OTf. [e] 2.5 mol% of L1CuOTf and 5 mol% of Et3N.

Scheme 3. Evidence for the pivotal role of the dinuclear copper complex A.

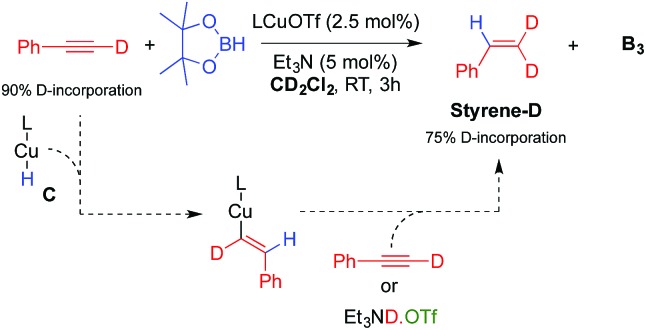

The other important species in our postulated mechanism is the copper hydride C, a type of complex that has been proposed to play a major role in a number of catalytic transformations.13 While there is still no report of a monomeric mono-ligated Cu hydride,14 a range of dimeric species have been described by us and others.15 An indication of L1CuH formation in this process is the observation of a small amount of styrene derivatives E in our experiments (Table 1). Indeed, copper hydrides are known to undergo 1,2-addition across alkynes to generate copper vinyl complexes, which by protonolysis give alkenes.15 Consistent with this hypothesis, a catalytic experiment using deuterium labelled phenyl acetylene under our optimized conditions, but in CD2Cl2 instead of C6D6 (Table 1, entry 6), afforded B3 and Styrene-D (75% D-incorporation) (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4. Evidence for the formation of the copper hydride C.

Conclusions

In summary, we have disclosed the first example of a highly selective dehydrogenative borylation of terminal alkynes with pinacolborane, using an inexpensive metal center supported by readily accessible ligands.16 Preliminary mechanistic studies suggest the pivotal role of a σ,π-bis(copper) acetylide A and a copper hydride C.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the DOE (DE-FG02-13ER16370).

Footnotes

References

- Hartwig J. F., Lennox A. J., Lloyd-Jones G. C. Acc. Chem. Res. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;2014;4543:864. 412. [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Schlecht S., Semple T. C., Hartwig J. F. Science. 2000;287:1995. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5460.1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho J. Y., Tse M. K., Holmes D., Maleczka Jr. R. E., Smith III M. R. Science. 2002;295:305. doi: 10.1126/science.1067074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig J. F., Mkhalid I. A., Barnard J. H., Marder T. B., Murphy J. M., Hartwig J. F. Chem. Soc. Rev. Chem. Rev. 2011;2010;40110:1992. 890. [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. I., Zhou J., Ozerov O. V., Lee C. I., Hirscher N. A., Zhou J., Bhuvanesh N., Ozerov O. V., Lee C. I., Shih W. C., Zhou J., Reibenspies J. H., Ozerov O. V., Lee C. I., DeMott J. C., Pell C. J., Christopher A., Zhou J., Bhuvanesh N., Ozerov O. V., Pell C. J., Ozerov O. V. J. Am. Chem. Soc. Organometallics. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Chem. Sci. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2013;2015;2015;2015;2015;135345462:3560. 3099, 14003, 6572, 720. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchimoto T., Utsugi H., Sugiura T., Horio S. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2015;357:77. [Google Scholar]

- Barbeyron R., Benedetti E., Cossy J., Vasseur J. J., Arseniyadis S., Smietana M. Tetrahedron. 2014;70:8431. [Google Scholar]

- Jin L., Tolentino D. R., Melaimi M., Bertrand G., Jin L., Romero E. A., Melaimi M., Bertrand G. Sci. Adv. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;2015;1137:e1500304. 15696. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1500304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For reviews on CAACs, see: Melaimi M., Soleilhavoup M., Bertrand G., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2010, 49 , 8810 Martin D., Melaimi M., Soleilhavoup M., Bertrand G., Organometallics, 2011, 30 , 5304, Soleilhavoup M., Bertrand G., Acc. Chem. Res., 2015, 48 , 256 . [Google Scholar]

- For the synthesis of CAACs, see: Lavallo V., Canac Y., Präsang C., Donnadieu B., Bertrand G., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2005, 44 , 5705 Jazzar R., Dewhurst R. D., Bourg J. B., Donnadieu B., Canac Y., Bertrand G., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2007, 46 , 2899, Jazzar R., Bourg J. B., Dewhurst R. D., Donnadieu B., Bertrand G., J. Org. Chem., 2007, 72 , 3492 . [Google Scholar]

- For other mechanistic studies, involving the transient formation of σ,π-bis(copper) acetylides, see: Rodionov V. O., Fokin V. V., Finn M. G., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2005, 44 , 2210 Himo F., Lovell T., Hilgraf R., Rostovtsev V. V., Noodleman L., Sharpless K. B., Fokin V. V., J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2005, 127 , 210, Ahlquist M., Fokin V. V., Organometallics, 2007, 26 , 4389, Straub B. F., Chem. Commun., 2007. , 3868, Nolte C., Mayer P., Straub B. F., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2007, 46 , 2101, Makarem A., Berg R., Rominger F., Straub B. F., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2015, 54 , 7431, Worrell B. T., Malik J. A., Fokin V. V., Science, 2013, 340 , 457 . [Google Scholar]

- Arduengo A. J., Krafczyk R., Schmutzler R. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:14523. [Google Scholar]

- For reviews, see: Egbert J. D., Cazin C. S. J., Nolan S. P., Catal. Sci. Technol., 2013, 3 , 912 Deutsch C., Krause N., Lipshutz B. H., Chem. Rev., 2008, 108 , 2916, Lipshutz B. H., Synlett, 2009. , 509 . [Google Scholar]

- For an example of diligated copper hydride, see: Lipshutz B. H., Frieman B. A., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2005, 44 , 6345 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey G. D., Donnadieu B., Soleilhavoup M., Bertrand G., Cox N., Dang H., Whittaker A. M., Lalic G., Uehling M. R., Rucker R. P., Lalic G., Suess A. M., Uehling M. R., Kaminsky W., Lalic G., Mankad N. P., Laitar D. S., Sadighi J. P., Semba K., Fujihara T., Xu T. H., Terao J., Tsuji Y., Jordan A. J., Wyss C. M., Bacsa J., Sadighi J. P., Suess A. M., Lalic G., Collins L. R., Riddlestone I. M., Mahon M. F., Whittlesey M. K., Wyss C. M., Tate B. K., Bacsa J., Gray T. G., Sadighi J. P. Chem.–Asian J. Tetrahedron. J. Am. Chem. Soc. J. Am. Chem. Soc. Organometallics. Adv. Synth. Catal. Organometallics. Synlett. Chem.–Eur. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011;2014;2014;2015;2004;2012;2016;2016;2015;2013;6701361372335435272152:402. 4219, 8799, 7747, 3369, 1542, 613, 1165, 14075, 12920. [Google Scholar]

- CAAC and NHC precursors are commercially available

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.