Abstract

Efforts at preventing pneumococcal disease are a national health priority, particularly in older adults and especially in post-acute and long-term care settings (PA/LTC). The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends that all adults ≥ 65, as well as adults aged 18–64 with specific risk factors, receive both the recently introduced polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccine against 13 pneumococcal serotypes (PCV13) as well as the polysaccharide vaccine against 23 pneumococcal serotypes (PPSV23). Nursing facility licensure regulations require facilities to assess the pneumococcal vaccination status of each resident, provide education regarding pneumococcal vaccination, and administer the appropriate pneumococcal vaccine when indicated. Sorting out the indications and timing for PCV13 and PPSV23 administration is complex, and presents a significant challenge to healthcare providers. Here, we discuss the importance of pneumococcal vaccination for older adults, detail AMDA – The Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine (The Society)’s recommendations for pneumococcal vaccination practice and procedures, and offer guidance to PA/LTC providers supporting the development and effective implementation of pneumococcal vaccine policies.

Keywords: Nursing Home, Pneumococcal Vaccines, Pneumococcal Infections, Aged, Policy

BACKGROUND

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has long recommended pneumococcal vaccination for older adults and those with certain chronic health conditions [1]. In 2014, ACIP released updated recommendations that call for the combined use of two separate pneumococcal vaccines [2]. Since their release, AMDA - The Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine (The Society) has fielded a number of inquiries from providers, facilities and surveyors regarding application of the ACIP recommendations to post-acute and long-term care (PA/LTC) settings. Questions received have focused on the impact of pneumococcal disease and pneumococcal vaccination in PA/LTC populations; financial coverage of the vaccine; and operational issues. Operational queries have included questions surrounding appropriate intervals for vaccination, whether nursing homes were required to offer either and/ or both vaccines, whether standing orders are allowed, and how to address lack of access to past vaccination history.

The Society strongly supports pneumococcal vaccination consistent with ACIP and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations. The Society also understands the need to respond to the various questions raised about pneumococcal vaccination in PA/LTC settings. To that end, The Society’s Infection Advisory Committee (IAC) conducted an environmental scan. This included assembling and thematically grouping questions received from September 2014 through May 2016. In addition, the IAC conducted a limited number of detailed interviews with select stakeholders, including state survey agency representatives, PA/LTC practitioners, and members of other professional societies. General information from survey citations was reviewed and pertinent literature and website reviews were conducted.

Based on this work, the IAC developed a series of educational and implementation tools to assist PA/LTC providers when assessing residents for pneumococcal vaccination needs. To further assist with guideline compliance, the materials present multiple clinical vignettes for practitioners [3]. Here, we present the results of these efforts, The Society’s policy statement, and introduce the tools developed.

PNEUMOCOCCAL DISEASE SERIOUSLY IMPACTS THE HEALTH OF OLDER ADULTS

Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus) remains a serious health threat in the United States, and one that is potentially preventable [2]. The leading bacterial cause of community acquired pneumonia (CAP), Streptococcus pneumoniae accounts for 20 to 60% of cases [4]. However, Streptococcus pneumoniae causes a variety of other infections as well, such as bacterial otitis media typically seen in children and invasive pneumococcal disease. The term invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) refers to any infection of a normally sterile site by Streptococcus pneumoniae. Examples of IPD include bacteremia, meningitis, arthritis, and endocarditis. IPD represents roughly one quarter of all pneumococcal infections and the incidence of IPD increases with age [5].

Before the advent of antibiotics in the early 1900’s, IPD was nearly always fatal [6]. The development of sulfa drugs, penicillin and subsequent antibiotics occasioned a significant reduction in pneumococcal-related morbidity and mortality [7]. Antibiotics became the mainstay of treatment for pneumococcal disease. Despite the overall reduction in mortality from pneumococcal disease, certain populations such as those ≥ 65 years of age as well as younger individuals with specific chronic medical conditions continue to experience high pneumococcal-related mortality rates [8–10].

Many factors contribute to the increased susceptibility of older adults to pneumococcal disease. Age-related changes in immune function, including immunosenescence, impaired splenic function and changes in the respiratory tract appear to play a role [11,12]. Residence in a post-acute or long-term care facility increases risk as evidenced by several documented outbreaks or clusters of pneumococcal disease [13–17]. Medication use, including polypharmacy, is also common in the treatment of older adults. Prescribed medications may include immunosuppressive drugs and central nervous system (CNS) active agents that can increase risk of aspiration and/or respiratory depression and further increase the risk of pneumococcal infection. The increased susceptibility and mortality among specific populations as well the emergence of antibiotic resistant strains drove the consideration of methods for primary prevention, namely the development of pneumococcal vaccines [4,7].

PNEUMOCOCCAL VACCINES AND ACIP RECOMMENDATIONS

Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV) was first commercially developed and licensed for use in 1977 as a 14-valent vaccine (PPSV14). In 1983, a 23-valent vaccine (PPSV23) was licensed (Table 1), and in 1984 the ACIP recommended the PPSV23 for adults ≥ 65 and those with chronic illness at increased risk of pneumococcal disease [1]. This recommendation extends to nearly all adults residing in PA/LTC facilities. The vaccine reduced the incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease in immunocompetent adults. However, limited studies led to questions about the effectiveness of PPSV23 in high-risk adults [18]. Unfortunately this hampered uptake of the vaccine throughout the 1990’s and early 2000’s, and ultimately prompted a search for a more effective vaccine.

TABLE 1.

Pneumococcal Vaccines Available in the United States

| Vaccine | Vaccine Type and Content | Brand Name (Manufacturer) |

Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| PPSV 23 | Pneumococcal polysaccharide – contains cell capsule antigens from 23 pneumococcus subtypes |

Pneumovax 23 (Merck) |

First pneumococcal vaccine. Licensed in 1983. |

| PCV 13 | Pneumococcal conjugate – contains cell capsule antigens from 13 pneumococcus subtypes combined with diphtheria antigen |

Prevnar 13 (Wyeth / Pfizer) |

Approved by FDA in 2010. Conjugate formulation was developed to enhance immunogenicity. |

| PCV 7 | Pneumococcal conjugate – contains cell capsule antigens from 7 common pneumococcus subtypes combined with diphtheria antigen |

Prevnar 7 (Wyeth / Pfizer) |

Licensed for children only. Not used in older adults. |

In 2000, a new 7-valent pneumococcal vaccine, the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7), was licensed for use in the pediatric population (<18 years of age) [19]. PCV7 reduced the rate of pneumococcal-related illness in children. Remarkably, administration of PCV7 to children also correlated with a marked reduction in the rate of hospitalizations due to pneumonia in older adults, even though this population did not receive the vaccine directly [20]. Of note, the effect decline in hospitalization rates for pneumonia was greatest among people ≥ 85 years [21]. Adoption of PCV7 has also been associated with a reduction in adult mortality from IPD [22]. In 2010, PCV7 was replaced with an expanded PCV13 vaccine. Given the reports of improved effectiveness of the conjugate vaccines, the Community Acquired Pneumonia Immunization Trial in Adults (CAPITA) was launched in the Netherlands, a country in which PPSV23 had not been administered widely [23]. The CAPITA study randomized almost 85,000 adults ≥ 65 years of age (>26,000 were 75 years or older) to receive either PCV13 or placebo. PCV13 reduced vaccine-type invasive pneumococcal disease by 75% and vaccine-type community acquired pneumonia by 45%. Unfortunately, the study did not include a comparison to PPSV23, so could not answer the question of which vaccine is more effective at preventing pneumococcal-related illnesses.

Several studies of PCV13 and PPSV23 affirm that even very frail individuals benefit from pneumococcal vaccination. Immunogenicity studies comparing PCV13 and PPSV23 in frail elderly patients have been conducted in both nursing home and hospital settings. Subjects recruited in these studies included very frail elderly individuals with significant levels of dependency and cognitive impairment. Regardless of setting, subjects were able to mount a significant antibody response, including those with no detectable baseline levels of immunity [24,25]. A placebo controlled study of PPSV23 conducted in 1006 Japanese nursing home residents found a significant reduction in pneumococcal and all cause pneumonia rates. This study also reported a striking 35% absolute risk reduction in deaths from pneumococcal pneumonia [26]. While PCV13 may elicit a stronger immune response [27,28], the incidence of infections caused by the strains covered by the vaccine have declined [2]. In contrast, while PPSV23 may be less immunogenic, it offers protection against more strains [27,28].

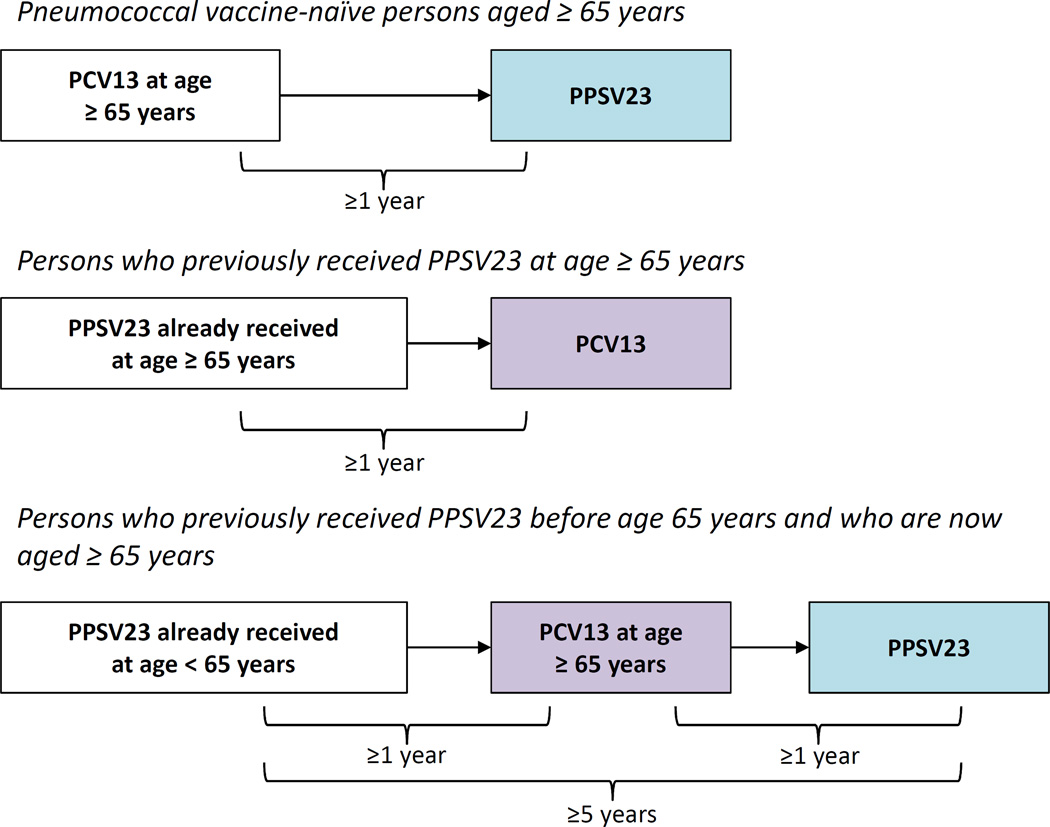

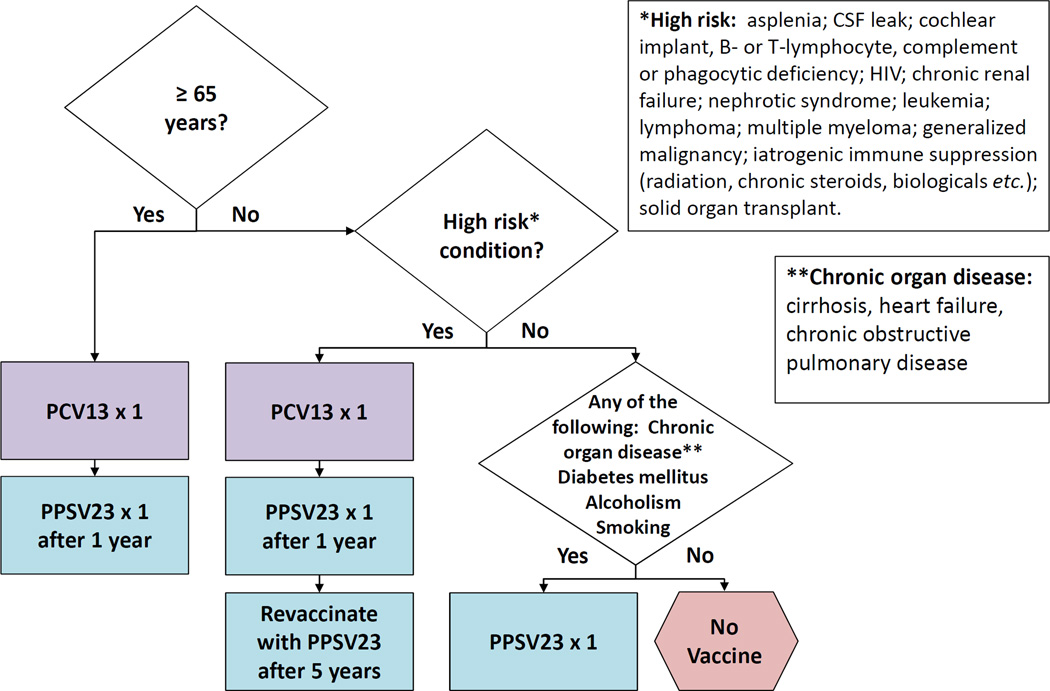

In 2014, weighing the totality of evidence available to date, the ACIP recommended the use of both vaccines in adults 65 years or older in addition to those with chronic health conditions [2]. The ACIP determined that use of both vaccines provided benefit surpassing that of either one alone. The 2014 ACIP recommendations included complex recommendations for intervals between vaccine administration. In 2015, the ACIP simplified the vaccine interval recommendations [29] with the intent to improve vaccine uptake as well as bring current recommendations into congruence with CMS coverage policies [30]. Table 2 lists current ACIP recommendations and Figure 1 shows the recommended dosing intervals for PCV13 and PPSV23 administration [29]. Figure 2 provides an algorithm to help guide determination of vaccine administration in vaccine-naïve adults based on age, high- and low-risk conditions [31]. Depending on their indications, adults may receive up to 3 doses of PPSV23 during their lifetime (2 doses at age <65 years; 1 dose at age ≥65 years), all of which should be given 5 years apart.

TABLE 2.

Summary of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended intervals, by risk and age groups, for adults with indications to receive to PCV13 and PPSV23.

| Risk group/Underlying medical conditiona | Intervals for PCV13–PPSV23b sequence, by age group |

Intervals for PPSV23–PCV13b sequence, by age group |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19–64 years |

≥65 years |

19–64 years |

≥65 years |

|

| No underlying chronic conditions | NAc | ≥1 year | NAc | ≥1 year |

| Immunocompetent persons | NA | ≥1 year | NA | ≥1 year |

| Chronic heart disease | ||||

| Chronic lung disease | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | ||||

| Alcoholism | ||||

| Chronic liver disease, cirrhosis | ||||

| Cigarette smoking | ||||

| Immunocompetent persons | ≥8 weeks |

≥8 weeks |

≥1 year | ≥1 year |

| Cerebrospinal fluid leak | ||||

| Cochlear implant | ||||

| Persons with functional or anatomic asplenia | ≥8 weeks |

≥8 weeks |

≥1 year | ≥1 year |

| Sickle cell disease/other hemaglobinopathy | ||||

| Congenital or acquired asplenia | ||||

| Immunocompromised persons | ≥8 weeks |

≥8 weeks |

≥1 year | ≥1 year |

| Congenital or acquired immunodeficiency | ||||

| Human immunodeficiency virus infection | ||||

| Chronic renal failure | ||||

| Nephrotic syndrome | ||||

| Leukemia | ||||

| Lymphoma | ||||

| Hodgkin disease | ||||

| Generalized malignancy | ||||

| Iatrogenic immunosuppression | ||||

| Solid organ transplant | ||||

| Multiple myeloma | ||||

Adapted from [29]

PCV13, polysaccharide-protein conjugate vaccine against 13 pneumococcal serotypes; PPSV23, polysaccharide vaccine against 23 pneumococcal serotypes.

NA, not applicable. Sequential use of PCV13 and PPSV23 is not recommended for these age and risk groups.

Figure 1.

Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended intervals for sequential use of PCV13 and PPSV23 for immunocompetent adults aged ≥65 years. **For adults aged ≥65 years with immunocompromising conditions, functional or anatomic asplenia, cerebrospinal fluid leaks, or cochlear implants, the recommended interval between PCV13 followed by PPSV23 is ≥8 weeks. For those for who previously received PPSV23 when aged <65 years and for whom an additional dose of PPSV23 is indicated when aged ≥65 years, this subsequent PPSV23 dose should be given ≥1 year after PCV13 and ≥5 years after the most recent dose of PPSV23. Depending on their indications, adults may receive up to 3 doses of PPSV23 during their lifetime (2 doses at age <65 years; 1 dose at age ≥65 years), all of which should be given 5 years apart. These materials were adapted from [29].

Figure 2.

Algorithm for Pneumococcal Immunization for Adults. These recommendations, based on [2,5], are for adults who have not previously received a pneumococcal vaccine. Figure adapted with permission from [31].

REGULATORY ATTEMPTS TO IMPROVE PNEUMOCOCCAL VACCINATION RATES IN PA/LTC FACILITIES

Several regulatory initiatives have been undertaken to improve pneumococcal vaccination rates in PA/LTC populations. In 2002, the United States Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) issued orders allowing the use of standing order programs in nursing homes for influenza and pneumococcal vaccination [32]. Research had shown standing order programs to be effective in improving immunization rates and in 2000, the ACIP had recommended their use in a variety of clinical settings [33,34]. Despite their explicit allowance, standing order programs were not widely adopted, and influenza and pneumococcal vaccination rates remained well below targets. This led the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to issue a new immunization standard (F334) in 2005 as part of the nursing facility conditions of participation [35]. This regulation requires PA/LTC facilities to assess the influenza and pneumococcal vaccination status of each resident, provide education about the vaccines and offer the vaccines to all eligible residents [36]. Additional 2009 updates to the PA/LTC facility infection control guidance (F441) emphasized the importance of vaccination by directing surveyors to investigate whether facilities have systems in place to ensure immunization of residents when assessing a facility’s overall infection control practices [36]. In July 2012, CMS began public reporting of a set of new quality measures. Included in these measures were two pertaining to pneumococcal vaccination: the percentage of short and long stay residents who have been assessed and appropriately given the pneumococcal vaccine [37].

By explicitly allowing and promoting standing order programs, promulgating immunization standards, tightening the survey investigative protocol for pneumococcal vaccination, and initiating public reporting of pneumococcal vaccination rates, CMS has made it clear that pneumococcal vaccination is a high priority. CMS expects facilities to have effective and current pneumococcal vaccination programs in place as part of their infection control activities.

BARRIERS TO PNEUMOCOCCAL IMMUNIZATION IN NURSING HOMES

The United States DHHS Healthy People 2020 Program has established a 90% pneumococcal vaccination rate goal for all adults (≥18 years) who reside in PA/LTC facilities. While pneumococcal vaccination rates among nursing home residents have improved from 67% in 2006, they have since stagnated around 80%. Moreover, concerns have been raised about the accuracy of this data, and it is possible that vaccination rates may be lower than those reported [38,39]. There are many potential barriers to vaccination in general including poor access to vaccines, lack of education, healthcare worker behaviors and attitudes, cultural factors and cost [40,41]. A full discussion of such barriers is beyond the scope of this paper. However there are several key points relevant to pneumococcal vaccination of PA/LTC residents that deserve comment.

First, PA/LTC practitioners have voiced skepticism regarding the benefits of pneumococcal vaccinations. PA/LTC practitioners appropriately recognize frailty as a characteristic of PA/LTC residents and a potential attenuator of vaccine response [24,31,42]. Pneumococcal disease poses a serious health threat to residents and one in which prevention, by necessity, must play a prominent role. The data presented above provides evidence supporting the use of pneumococcal vaccine even in frail populations. While not as effective compared to use in younger and/or healthier populations, pneumococcal vaccination still provides a significant benefit to frail recipients. The Society has established a clear policy statement on pneumococcal vaccination in the PA/LTC setting, detailed in the following section.

Second, obtaining an accurate vaccine history is a challenge. Despite the prevalence of electronic health records, transfer of important vaccination information remains suboptimal and poses challenges as recently highlighted in the National Quality Forum’s 2015 report, Priority Setting for Healthcare Performance Measurement: Addressing Performance Measure Gaps for Adult Immunizations [43]. Facilities should seek ways to improve communication about a resident’s vaccination status at admission and discharge. Third, there have been questions regarding reimbursement from Medicare for pneumococcal vaccines. As PCV13 and PPSV23 are ACIP recommended vaccines, CMS has issued statements of coverage for both vaccines as a Part B benefit [23]. Fourth, and the most challenging barrier, is the complexity of vaccine recommendations. Given the complexities of current ACIP pneumococcal vaccination recommendations and the unique features of PA/LTC settings, it is understandable that pneumococcal vaccinations pose a challenge to many PA/LTC providers. As noted, ACIP recommendations have been simplified and algorithms such as the ones in Figures 1 and 2 exist to guide practitioners in selecting the right vaccine for each resident. Still, facilities will need to be familiar with specific indications for the vaccine and perform a thoughtful assessment of each resident.

POLICY STATEMENT, RECOMMENDATIONS AND TOOLS FROM THE SOCIETY’S INFECTION ADVISORY COMMITTEE (IAC)

AMDA – The Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine (The Society) strongly supports pneumococcal vaccination of PA/LTC residents and the need for continued efforts to improve pneumococcal vaccination rates. Box 1 details The Society’s policy statement regarding pneumococcal vaccination developed by the Infection Advisory Committee (IAC) and adopted by The Society.

BOX 1. AMDA - THE SOCIETY FOR POST-ACUTE AND LONG-TERM CARE MEDICINE POLICY STATEMENT ON PNEUMOCOCCAL VACCINATION.

The Society strongly advocates that Post-Acute and Long-Term Care (PA/LTC) facilities and providers establish and maintain a pneumococcal vaccination program that provides residents with access to current Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended pneumococcal vaccinations.

Such a program would include a requirement to assess PA/LTC residents for their pneumococcal vaccination status and to administer and document appropriate pneumococcal vaccinations in accordance with current ACIP and CDC guidance, unless the PA/LTC resident declines or has a medical contraindication or allergy,

In addition, The Society recommends PA/LTC facilities and providers demonstrate an ongoing commitment to Quality Assessment and Performance Improvement by evaluating and addressing their pneumococcal vaccination programs if vaccine acceptance rates fall below U.S. Department of Health and Human Services goals.

The Society has created a series of educational and implementation tools to assist PA/LTC providers when assessing residents for pneumococcal vaccination needs. Available at the Society’s website and found in Appendices 1–3, these tools were developed by the IAC and approved by The Society’s Board. They are introduced here with the aim of supporting provider efforts to improve pneumococcal vaccination rates among the PA/LTC population.

The tools include:

A Pneumococcal Vaccination Guidance document formatted using a frequently asked question approach. The Guidance addresses common pneumococcal vaccination questions, and presents a series of common clinical vignettes designed to help providers select appropriate vaccination strategies. (see Appendix 1)

A Pneumococcal Vaccination Coverage document that also uses a frequently asked question approach to answer questions about CMS coverage of pneumococcal vaccinations. (see Appendix 2)

A Resident Pneumococcal Vaccination Assessment Note which helps nursing home staff complete the required resident pneumococcal vaccination assessment through use of a template note. (see Appendix 3)

The tools are available free of charge to assist PA/LTC providers and facilities. They can be found in the online appendix, as well as through The Society website [Pneumococcal Vaccination Guidance for PA / LTC Facilities]. The Society plans to update these materials as ACIP recommendations change. Finally, The Society welcomes feedback on this material in an effort to make improvements and to continue to support PA/LTC practitioners and facilities in their efforts to vaccinate their residents as an effective means to reduce the risk of infection with S. pneumoniae and improve clinical care.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Update: pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine usage--United States. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 1984;33:273–276. 281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tomczyk S, Bennett NM, Stoecker C, et al. Use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine among adults aged ≥65 years: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2014;63:822–825. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meisel ZF, Metlay JP, Sinnenberg L, et al. A randomized trial testing the effect of narrative vignettes versus guideline summaries on provider response to a professional oganization clinical policy for safe opioid prescribing. [Accessed 2 July 2016];Ann. Emerg. Med. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.03.007. 0. Available at: http://www.annemergmed.com/article/S0196064416002055/abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones RN, Jacobs MR, Sader HS. Evolving trends in Streptococcus pneumoniae resistance: implications for therapy of community-acquired bacterial pneumonia. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2010;36:197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine for adults with immunocompromising conditions: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2012;61:816–819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tilghman R, Finland M. Clinical significance of bacteremia in pneumococcic pneumonia. Arch. Intern. Med. 1937;59:602–619. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rocha P, Baleeiro C, Tunkel A. Impact of Antimicrobial Resistance on the Treatment of Invasive Pneumococcal Infections. Curr. Infect. Dis Rep. 2000;2:399–408. doi: 10.1007/s11908-000-0066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Navarro-Torné A, Dias JG, Hruba F, et al. Risk factors for death from invasive pneumococcal disease, Europe, 2010. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015;21:417–425. doi: 10.3201/eid2103.140634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Torres A, Blasi F, Dartois N, Akova M. Which individuals are at increased risk of pneumococcal disease and why? Impact of COPD, asthma, smoking, diabetes, and/or chronic heart disease on community-acquired pneumonia and invasive pneumococcal disease. Thorax. 2015;70:984–989. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-206780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feikin DR, Schuchat A, Kolczak M, et al. Mortality from invasive pneumococcal pneumonia in the era of antibiotic resistance, 1995–1997. Am. J. Public Health. 2000;90:223–229. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.2.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simell B, Lahdenkari M, Reunanen A, Käyhty H, Väkeväinen M. Effects of ageing and gender on naturally acquired antibodies to pneumococcal capsular polysaccharides and virulence-associated proteins. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2008;15:1391–1397. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00110-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krone CL, van de Groep K, Trzciński K, Sanders EAM, Bogaert D. Immunosenescence and pneumococcal disease: an imbalance in host–pathogen interactions. Lancet Respir. Med. 2:141–153. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70165-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nuorti JP, Butler JC, Crutcher JM, et al. An outbreak of multidrug-resistant pneumococcal pneumonia and bacteremia among unvaccinated nursing home residents. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998;338:1861–1868. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199806253382601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas HL, Gajraj R, Slack MPE, et al. An explosive outbreak of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype-8 infection in a highly vaccinated residential care home, England, summer 2012. Epidemiol. Infect. 2015;143:1957–1963. doi: 10.1017/S0950268814002490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan CG, Ostrawski S, Bresnitz EA. A preventable outbreak of pneumococcal pneumonia among unvaccinated nursing home residents in New Jersey during 2001. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2003;24:848–852. doi: 10.1086/502148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olver WJ, Cavanagh J, Quinn M, Diggle M, Edwards GFS. Investigation and control of a cluster of penicillin non-susceptible Streptococcus pneumoniae infections in a care home. J. Hosp. Infect. 2008;70:80–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuroki T, Ishida M, Suzuki M, et al. Outbreak of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 3 pneumonia in extremely elderly people in a nursing home unit in Kanagawa, Japan, 2013. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2014;62:1197–1198. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fine MJ, Smith MA, Carson CA, et al. Efficacy of pneumococcal vaccination in adults: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch. Intern. Med. 1994;154:2666–2677. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1994.00420230051007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Preventing pneumococcal disease among infants and young children. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm. Rep. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. Recomm. Rep. Cent. Dis. Control. 2000;49:1–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pilishvili T, Lexau C, Farley MM, et al. Sustained reductions in invasive pneumococcal disease in the era of conjugate vaccine. J. Infect. Dis. 2010;201:32–41. doi: 10.1086/648593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Griffin MR, Zhu Y, Moore MR, Whitney CG, Grijalva CG. U.S. hospitalizations for pneumonia after a decade of pneumococcal vaccination. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:155–163. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grau I, Ardanuy C, Cubero M, Benitez MA, Liñares J, Pallares R. Declining mortality from adult pneumococcal infections linked to children’s vaccination. J. Infect. 2016;72:439–449. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonten MJM, Huijts SM, Bolkenbaas M, et al. Polysaccharide conjugate vaccine against pneumococcal pneumonia in adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:1114–1125. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacIntyre CR, Ridda I, Gao Z, et al. A randomized clinical trial of the immunogenicity of 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine compared to 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine in frail, hospitalized elderly. PLOS ONE. 2014;9:e94578. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Namkoong H, Funatsu Y, Oishi K, et al. Comparison of the immunogenicity and safety of polysaccharide and protein-conjugated pneumococcal vaccines among the elderly aged 80 years or older in Japan: an open-labeled randomized study. Vaccine. 2015;33:327–332. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maruyama T, Taguchi O, Niederman MS, et al. Efficacy of 23-valent pneumococcal vaccine in preventing pneumonia and improving survival in nursing home residents: double blind, randomised and placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c1004. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jackson LA, Gurtman A, van Cleeff M, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of a 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine compared to a 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in pneumococcal vaccine-naive adults. Vaccine. 2013;31:3577–3584. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.04.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paradiso PR. Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine for Adults: A New Paradigm. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;55:259–264. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kobayashi M, Bennett NM, Gierke R, et al. Intervals Between PCV13 and PPSV23 Vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2015;64:944–947. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6434a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Medicare. Modifications to Medicare part B coverage of pneumococcal vaccinations. [Accessed 2 July 2016];2015 Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prevention/PrevntionGenInfo/Health-Observance-Mesages-New-Items/2015-01-29-Pneumococcal.html.

- 31.Perez F, Jump RLP. New developments in adult vaccination: Challenges and opportunities to protect vulnerable veterans From pneumococcal disease. Fed. Pract. 2015;32:12–18. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Federal Register | Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Conditions of Participation: Immunization Standards for Hospitals, Long-Term Care Facilities, and Home Health Agencies. [Accessed 31 August 2016]; Available at: https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2002/10/02/02-25096/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-conditions-of-participation-immunization standards-for-hospitals. [PubMed]

- 33.Bardenheier BH, Shefer A, McKibben L, Roberts H, Rhew D, Bratzler D. Factors predictive of increased influenza and pneumococcal vaccination coverage in long-term care facilities: The CMS-CDC standing orders program project. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2005;6:291–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Postema AS, Breiman RF National Vaccine Advisory Committee. Adult immunization programs in nontraditional settings: quality standards and guidance for program evaluation. MMWR Recomm. Rep. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. Recomm. Rep. Cent. Dis. Control. 2000;49:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Federal Register | Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Condition of Participation: Immunization Standard for Long Term Care Facilities. [Accessed 31 August 2016]; Available at: https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2005/10/07/05-19987/medicare-and-medicaid programs-condition-of-participation-immunization-standard-for-long-term-care. [PubMed]

- 36.Medicare State Operations Manual, Appendix PP: Interpretive Guidelines for Long-Term Care Facilities. [Accessed 31 August 2016]; Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Internet-Only-Manuals-IOMs-Items/CMS1201984.html.

- 37.Smith, Laura, Zheng, Nan Tracy, Kissam, Stephanie, et al. Nursing Home MDS 3.0 Quality Measures: Final Analytic Report. [Accessed 31 August 2016]; Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/NursingHomeQualityInits/NHQIQualityMeasures.html.

- 38.Pu Y, Dolar V, Gucwa AL. A comparative analysis of vaccine administration in urban and non-urban skilled nursing facilities. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:148. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0320-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Data Chart | Healthy People 2020. [Accessed 1 September 2016]; Available at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/data/Chart/4672?category=1&by=Total&fips=-1.

- 40.Nace DA. Improving immunization rates in long-term care: Where the forest stops and the trees begin. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2008;9:617–621. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jessop AB, Hausman AJ. Pneumococcal vaccination in pennsylvania nursing homes: factors associated with vaccination level. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2002;3:347–351. doi: 10.1097/01.JAM.0000035740.73159.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hamza SA, Mousa SM, Taha SE, Adel LA, Samaha HE, Hussein DA. Immune response of 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccinated elderly and its relation to frailty indices, nutritional status, and serum zinc levels. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2012;12:223–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2011.00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.NQF. Priority Setting for Healthcare Performance Measurement: Addressing Performance Measure Gaps for Adult Immunizations. [Accessed 1 September 2016]; Available at: http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2014/08/Priority_Setting_for_Healthcare_Performance_Measurement__Addressing_Performance_Measure_Gaps_for_Adult_Immunization s.aspx. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.