Abstract

Background

The Physician Payments Sunshine Act (PSSA) is a government initiative that requires all biomedical companies to publicly disclose payments to physicians through the Open Payments Program (OPP). The goal of this study was to utilize the OPP database and evaluate all non-research related financial transactions between plastic surgeons and biomedical companies.

Methods

Using the first wave of OPP data published on September 30, 2014, we studied the national distribution of industry payments made to plastic surgeons during a five month period. We explored whether a plastic surgeon’s scientific productivity, (as determined by their h-index), practice setting (private versus academic), geographic location, and subspecialty were associated with payment amount.

Results

Plastic surgeons (N=4,195) received a total of $5,278,613. The median (IQR) payment to a plastic surgeon was $115($35–298); mean $1,258. The largest payment to an individual was $341,384. The largest payment category was non-CEP speaker fees ($1,709,930) followed by consulting fees ($1,403,770). Plastic surgeons in private practice received higher payments per surgeon compared to surgeons in academic practice (median [IQR] $165[$81 – $441] vs. median [IQR] $112 [$33–$291], rank-sum p<0.001). Among academic plastic surgeons, a higher h-index was associated with 77% greater chance of receiving at least $1000 in total payments (RR/10 unit h-index increase=1.47 1.77 2.11, p<0.001). This association was not seen among plastic surgeons in private practice (RR=0.89 1.09 1.32, p<0.4).

Conclusion

Plastic surgeons in private practice receive higher payments from industry. Among academic plastic surgeons, higher payments were associated with higher h-indices.

Keywords: Open Payments Program, Physician Payments Sunshine Act, Industry Physician Conflicts-of-Interest, Academic Productivity, h-index, Bibliometrics, Plastic Surgery

INTRODUCTION

As part of the Physician Payments Sunshine Act (PPSA), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) implemented The Open Payments Program (OPP) to create transparency regarding the financial relationships between physicians and the biomedical industry (1). Manufacturers of drugs, medical devices and supplies are now mandated to submit their payment records and other “transfers of value” made to physicians and teaching hospitals to CMS. The database does not report industry payments to resident physicians and trainees. On September 30, 2014, five months of payment data were made publically available (2). The stated rationale is to allow patients to identify potential conflicts-of-interest (COI), and to enable them to make more informed decisions when choosing a health care provider (HCP) (3).

Financial interactions between the pharmaceutical and the biomedical industry and physicians are pervasive (4, 5). In 2004, market research companies estimated that U.S. pharmaceutical companies spent $57.5 billion, or 24.4% of their revenue, on marketing (6). During this time frame a national survey of 3,167 U.S. physicians reported that 83% of physicians received gifts and 28% received payments for consulting, lecturing, or enrolling patients in trials (7). These findings (4–7) have received much speculation, but national statistics on financial transactions between industry and healthcare providers are sparse. The OPP represents the first nationwide report of financial relationships that have been confirmed by both parties.

Plastic surgery, as a field, thrives on innovation. It is well accepted that collaboration between industry and surgeons is essential for the evolution of new products that will improve patient care (8, 9). Recently, several surgical specialties have published their results from the OPP database (10–12). However, the scope and nature of these collaborations have never been explored within the field of plastic surgery. The purpose of this study was to utilize the newly-released OPP database and comprehensively evaluate all non-research-related financial transactions between plastic surgeons and biomedical companies We hypothesized that plastic surgeons, due to the technical and innovative aspects of the field, would have more extensive relationships with industry when compared to other healthcare providers, and that industry payment amounts would differ by subspecialty, practice settings, and scientific productivity. The specific aims of the study were the following: 1) to identify a cohort of plastic surgeons who received non-research payments by industry 2) compare payments to plastic surgeons to other healthcare providers, 3) compare payments of plastic surgeons by subspecialty, geographic distribution, practice setting (private versus academic), and payment category, and 4) examine the association between payments received and a plastic surgeon’s H-index, a measure of scientific productivity (10).

METHODS

Study Population

All physicians whose reported professions in the OPP database were either: Plastic Surgery, Plastic Surgery-Hand, Plastic Surgery of the Head and Neck (Craniofacial), Otolaryngologists specializing in Facial Plastic Surgery (Oto) and Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. To study whether industry payments differed among academic versus non-academic plastic surgeons, we identified all plastic surgery residency training programs approved by the American Council of Graduate Medical Education, via the “American Council of Academic Plastic Surgeons” website (http://www.acaplasticssurgeons.org/program-lists). We visited each program’s website and collected data for each listed fulltime faculty member, and labeled these plastic surgeons as “academic.” Part time or affiliated faculty members were characterized as private practice plastic surgeons as were any plastic surgeons with no residency program affiliation.

Data Sources and Linkages

Payments made to plastic surgeons between August 1, 2013 and December 31, 2013 were obtained from the OPP dataset, available on the CMS website (http://www.cms.gov/openpayments; accessed September 30, 2014). Company and/or stock ownership data were not included in this study. Physician-level payments were aggregated using a unique physician identification number.

Payments Made to All Health Care Providers and Plastic Surgeons

The OPP dataset was used to ascertain the total amount of payments made by industry to all Health Care Providers (HCP). HCP consisted of physicians, dentists, podiatrist and nurse practitioners. This was then compared to the total amount of payments made to plastic surgeons.

Distribution of Payments Made to Plastic Surgeons

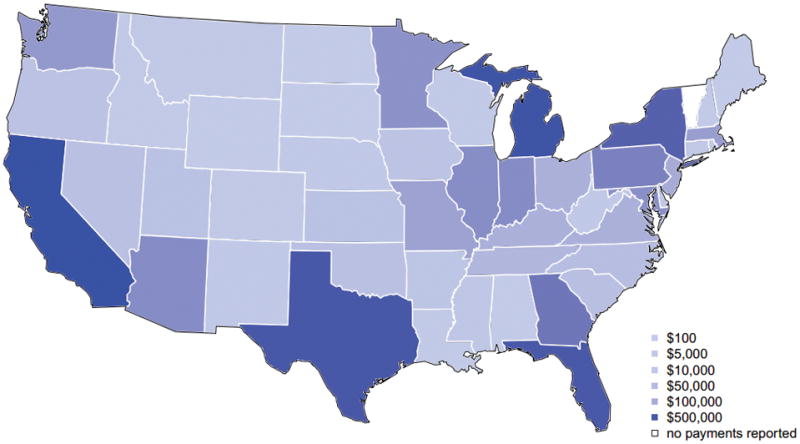

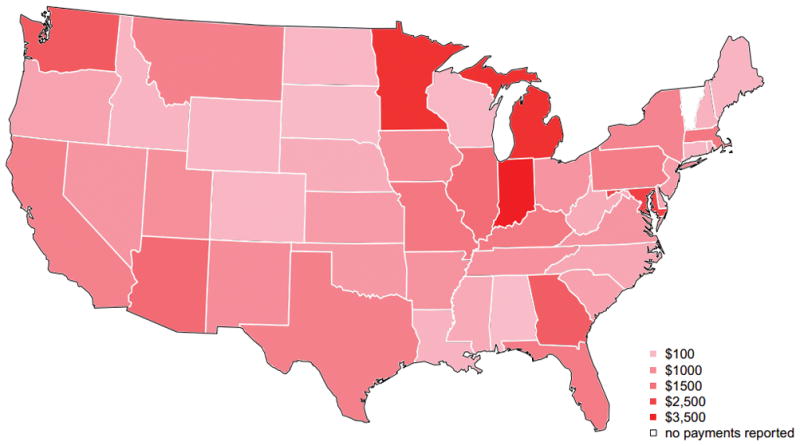

The total amount of money that each plastic surgeon received was categorized as follows: less than $100, $100–$999, $1,000–$9,999, $10,000–$99,999, and > $100,000 and presented as bar graphs. All companies and their sum of payments made to plastic surgeons were identified (Appendix 1). Payments of the ten highest paying companies and their distribution by categories were shown. Heat maps were used to show the geographic distribution of industry payments collectively by state, as well as the average payments per plastic surgeon in each state.

Appendix 1.

Payments Made to Plastic Surgeons by Company

| Company | Total Amount ($) | Mean Payment ($) | Median Payment ($) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allergan Inc. | 1,792,491.00 | 309.00 | 20.35 |

| Mentor Worldwide | 873,833.30 | 453.70 | 42.10 |

| LifeCell Corpora | 840,832.30 | 372.38 | 84.09 |

| Smith & Nephew, Inc. | 448,881.60 | 361.42 | 33.38 |

| Sientra, Inc. | 124,870.20 | 175.38 | 93.73 |

| Biomet, Inc. | 118,293.50 | 1,171.22 | 27.07 |

| Merz North Ameri | 78,342.70 | 113.54 | 21.50 |

| KCI USA, Inc. | 77,934.60 | 537.48 | 47.26 |

| AXOGEN | 77,499.26 | 610.23 | 80.11 |

| DePuy Synthes | 72,352.43 | 338.10 | 34.98 |

| Integra LifeScience | 67,483.70 | 312.42 | 51.10 |

| C. R. Bard, Inc. | 63,107.22 | 202.27 | 38.40 |

| Musculoskeletal | 58,487.38 | 255.40 | 47.47 |

| Stryker Corp. | 57,053.72 | 372.90 | 64.82 |

| Entellus Medical | 51,303.00 | 123.03 | 13.24 |

| Pacira Pharmaceutial. | 27,597.10 | 191.65 | 28.71 |

| Valeant Pharmaceuticals | 25,411.77 | 770.05 | 500.00 |

| Ethicon Inc. | 21,485.20 | 130.21 | 31.16 |

| Intersect ENT, Inc. | 20,750.95 | 159.62 | 105.13 |

| Intuitive Surgical | 20,732.86 | 329.09 | 27.00 |

| DJO Global, Inc. | 20,397.41 | 2,266.38 | 28.99 |

| MicroAire Surgical | 19,343.66 | 1,018.09 | 600.00 |

| Novadaq | 19,273.60 | 1,927.36 | 240.90 |

| SI-Bone, Inc. | 19,200.00 | 4,800.00 | 4,800.00 |

| Auxilium Pharmaceutical | 19,004.36 | 126.70 | 66.24 |

| Ellman International | 18,010.83 | 1,385.45 | 200.00 |

| Merz Pharmaceutical | 15,161.05 | 2,526.84 | 1,173.32 |

| Molnlycke Health | 14,171.68 | 708.58 | 99.16 |

| Phadia US Inc. | 13,356.94 | 392.85 | 19.65 |

| Bacterin Interna | 11,240.72 | 624.48 | 70.71 |

| CSL Behring | 10,280.00 | 642.50 | 765.00 |

| Molnlycke Health | 9,219.18 | 2,304.80 | 2,042.03 |

| KLS Martin L.P. | 8,997.81 | 230.71 | 94.00 |

| Meda Pharmaceutical | 8,867.93 | 59.52 | 16.05 |

| Megadyne Medical | 8,393.45 | 1,398.91 | 185.20 |

| Pfizer Inc. | 7,407.70 | 108.94 | 16.33 |

| Midmark Corporat | 7,159.74 | 2,386.58 | 2,413.59 |

| Medtronic Xomed, | 7,061.83 | 53.10 | 25.89 |

| Medline | 6,122.45 | 437.32 | 35.45 |

| Acclarent, Inc | 5,952.61 | 35.43 | 20.31 |

| Harvest Technolo | 5,941.05 | 990.18 | 669.28 |

| Cardiovascular S | 5,556.32 | 555.63 | 58.82 |

| Forest Laboratory | 4,975.97 | 276.44 | 65.82 |

| Boston Scientific | 4,912.66 | 350.90 | 124.97 |

| ACUMED LLC | 4,668.08 | 186.72 | 63.25 |

| Teva Pharmaceuticals | 4,344.36 | 98.74 | 12.79 |

| Merck Sharp & Do | 4,097.58 | 31.04 | 14.25 |

| Henry Schein, Inc. | 3,864.35 | 94.25 | 64.28 |

| Medical Modeling | 3,142.14 | 314.21 | 176.01 |

| Applied Medical | 3,116.10 | 207.74 | 50.00 |

| Alcon Laboratories | 3,000.80 | 30.31 | 14.48 |

| Janssen Pharmace | 2,836.75 | 37.33 | 17.84 |

| Ascension Orthop | 2,791.47 | 139.57 | 38.00 |

| Kensey Nash | 2,697.52 | 385.36 | 400.00 |

| Anika Therapeutic | 2,614.91 | 1,307.46 | 1,307.46 |

| Shire US Holding | 2,556.25 | 21.85 | 12.95 |

| Vioptix Inc | 2,480.53 | 310.07 | 143.25 |

| Covidien Sales L | 2,367.87 | 59.20 | 21.95 |

| Cook Incorporated | 2,329.44 | 36.40 | 17.13 |

| Arthrex, Inc. | 2,037.70 | 1,018.85 | 1,018.85 |

| W. L. Gore & Ass | 1,488.87 | 135.35 | 37.14 |

| Takeda Pharmaceutical | 1,473.12 | 37.77 | 17.14 |

| Toshiba America | 1,431.05 | 1,431.05 | 1,431.05 |

| Osteomed LLC | 1,430.98 | 40.89 | 16.67 |

| Mylan Inc. | 1,358.63 | 19.98 | 13.95 |

| Sunovion | 1,328.13 | 21.42 | 13.21 |

| Baxter Healthcar | 1,310.68 | 29.79 | 18.07 |

| AstraZeneca | 1,271.03 | 24.92 | 16.68 |

| Olympus America | 1,158.22 | 44.55 | 21.56 |

| Integra LifeSci | 1,104.11 | 44.16 | 22.97 |

| Mallinckrodt LLC | 1,046.43 | 26.16 | 15.56 |

| Onyx | 1,029.64 | 343.21 | 18.88 |

| Cochlear Ltd | 1,019.59 | 42.48 | 21.05 |

| Genentech, Inc. | 987.13 | 30.85 | 15.57 |

| Abeon Medical | 915.85 | 915.85 | 915.85 |

| ArthroCare Corpo | 874.06 | 38.00 | 20.75 |

| DUSA | 779.76 | 41.04 | 14.09 |

| Sanofi and Genzy | 737.63 | 28.37 | 15.85 |

| Boehringer Ingel | 724.89 | 51.78 | 40.32 |

| Wound Care Techn | 700.48 | 100.07 | 88.80 |

| BIOVENTUS LLC | 619.53 | 68.84 | 24.24 |

| Reckitt Benckise | 603.36 | 54.85 | 61.56 |

| Horizon Pharma | 598.93 | 12.74 | 5.93 |

| Santarus, Inc. | 587.59 | 53.42 | 18.06 |

| Covidien LP | 587.47 | 117.49 | 140.00 |

| Bristol-Myers Sq | 573.01 | 28.65 | 17.38 |

| Cubist | 543.28 | 45.27 | 15.96 |

| Extremity Medical | 535.61 | 178.54 | 106.67 |

| St. Jude Medical | 510.31 | 170.10 | 166.41 |

| AngioDynamics, Inc. | 502.65 | 251.33 | 251.33 |

| Hollister Incorp | 465.95 | 42.36 | 23.25 |

| Medtronic Vascul | 445.13 | 111.28 | 132.84 |

| Karlstorz Endosc | 425.89 | 35.49 | 23.27 |

| Novartis Pharmac | 389.96 | 35.45 | 22.23 |

| Taro Pharmaceuti | 388.09 | 97.02 | 62.08 |

| Small Bone Innov | 356.78 | 356.78 | 356.78 |

| Pacific Medical, Inc. | 355.73 | 118.58 | 42.84 |

| Medtronic USA, Inc. | 276.10 | 69.03 | 76.73 |

| The Medicines Co | 268.36 | 38.34 | 12.98 |

| Applied Medical | 268.00 | 134.00 | 134.00 |

| Convatec Inc. | 266.27 | 33.28 | 26.55 |

| Apollo Surgical | 250.00 | 250.00 | 250.00 |

| Cyberonics, Inc. | 244.90 | 81.63 | 82.84 |

| Regeneron Pharma | 242.29 | 60.57 | 64.85 |

| LEO Pharma AS | 239.34 | 19.95 | 13.99 |

| Cumberland Pharm | 233.92 | 29.24 | 15.09 |

| OmniGuide, Inc. | 229.13 | 19.09 | 19.57 |

| ABL Medical, LLC | 210.05 | 105.03 | 105.03 |

| Vansen Pharma, Inc. | 208.86 | 69.62 | 96.20 |

| Abiomed | 201.83 | 201.83 | 201.83 |

| diaDexus, Inc. | 201.65 | 100.83 | 100.83 |

| Salix Pharmaceut | 199.02 | 33.17 | 16.03 |

| Spiracur Inc. | 193.58 | 32.26 | 16.66 |

| Systagenix Wound | 182.02 | 15.17 | 13.43 |

| Amgen Inc. | 179.55 | 25.65 | 14.93 |

| Carl Zeiss Medit | 169.62 | 84.81 | 84.81 |

| Dendreon Corpora | 163.54 | 14.87 | 14.58 |

| Avinger Inc. | 154.73 | 77.37 | 77.37 |

| Otsuka America P | 149.66 | 21.38 | 19.08 |

| AbbVie, Inc. | 147.71 | 14.77 | 15.48 |

| RTI Surgical, In | 145.58 | 29.12 | 12.27 |

| Vertex | 144.83 | 36.21 | 17.38 |

| Eisai Inc. | 143.47 | 23.91 | 21.93 |

| Alk-Abello, Inc | 136.45 | 27.29 | 13.40 |

| Grifols USA, LLC | 131.25 | 43.75 | 15.59 |

| Daiichi Sankyo I | 131.07 | 131.07 | 131.07 |

| Optimer | 130.35 | 65.18 | 65.18 |

| American Medical | 130.00 | 130.00 | 130.00 |

| Luitpold Pharmac | 125.24 | 6.26 | 7.35 |

| Insys Therapeuti | 125.00 | 125.00 | 125.00 |

| Sandoz Inc. | 123.35 | 41.12 | 16.58 |

| Depomed, Inc. | 122.52 | 20.42 | 14.05 |

| Purdue Pharma L. | 121.20 | 15.15 | 15.34 |

| Novo Nordisk Inc | 119.21 | 39.74 | 13.90 |

| Alexion Pharmace | 110.62 | 110.62 | 110.62 |

| Endogastric Solu | 107.91 | 35.97 | 18.62 |

| Acorda Therapeut | 107.90 | 35.97 | 14.36 |

| Novartis Vaccine | 102.70 | 102.70 | 102.70 |

| Team 1 Orthopaed | 99.72 | 99.72 | 99.72 |

| Gilead Sciences | 97.66 | 97.66 | 97.66 |

| Astellas Pharma | 95.82 | 47.91 | 47.91 |

| ResMed Corp | 94.63 | 31.54 | 32.30 |

| NDI Medical, LLC | 90.73 | 22.68 | 19.49 |

| Coopervision Inc | 88.65 | 88.65 | 88.65 |

| Jazz Pharmaceuti | 88.55 | 44.28 | 44.28 |

| Janssen Research | 86.52 | 86.52 | 86.52 |

| Wright Medical T | 85.08 | 42.54 | 42.54 |

| Actavis Pharma I | 84.16 | 84.16 | 84.16 |

| Aptalis Pharma U | 80.69 | 20.17 | 19.95 |

| Medtronic Sofamo | 77.03 | 38.52 | 38.52 |

| Lupin Pharmaceut | 77.02 | 19.26 | 12.88 |

| Coloplast Corp | 74.78 | 37.39 | 37.39 |

| Johnson & Johnso | 74.61 | 37.31 | 37.31 |

| Atos Medical Inc | 74.42 | 37.21 | 37.21 |

| MED-EL Corporati | 71.74 | 71.74 | 71.74 |

| Par Pharmaceutic | 65.78 | 32.89 | 32.89 |

| Promius Pharma L | 63.22 | 21.07 | 19.81 |

| Brainlab, Inc. | 61.56 | 20.52 | 27.06 |

| Cytori Therapeut | 61.29 | 61.29 | 61.29 |

| Atrium Medical C | 59.54 | 29.77 | 29.77 |

| Reliance Medical | 58.94 | 58.94 | 58.94 |

| BTG Internationa | 58.24 | 58.24 | 58.24 |

| Shionogi Inc | 51.62 | 25.81 | 25.81 |

| Maquet Cardiovas | 50.79 | 50.79 | 50.79 |

| Warner Chilcott | 50.08 | 16.69 | 14.16 |

| Sensus Healthcar | 50.00 | 50.00 | 50.00 |

| Hospira Worldwid | 45.57 | 15.19 | 14.22 |

| Spectrum Pharmac | 41.67 | 20.84 | 20.84 |

| Celgene Corporat | 41.58 | 20.79 | 20.79 |

| Bayer HealthCare | 38.59 | 12.86 | 11.32 |

| Noven Pharmaceut | 34.16 | 17.08 | 17.08 |

| Globus Medical, | 33.49 | 16.75 | 16.75 |

| Abbott Laborator | 33.35 | 33.35 | 33.35 |

| AlloSource | 32.00 | 16.00 | 16.00 |

| Terumo Cardiovas | 31.91 | 31.91 | 31.91 |

| Ranbaxy Inc. | 29.97 | 14.99 | 14.99 |

| UCB, Inc. | 27.06 | 13.53 | 13.53 |

| Cordis Corporati | 26.97 | 26.97 | 26.97 |

| Tenex Health Inc | 26.33 | 26.33 | 26.33 |

| Tactile Systems | 25.96 | 12.98 | 12.98 |

| Ironwood Pharmac | 25.41 | 25.41 | 25.41 |

| ViroPharma Incor | 25.20 | 12.60 | 12.60 |

| Aesculap Implant | 24.00 | 24.00 | 24.00 |

| HILL-ROM HOLDING | 23.63 | 23.63 | 23.63 |

| AMAG Pharmaceuti | 22.57 | 11.29 | 11.29 |

| BIOTRONIK INC. | 22.47 | 22.47 | 22.47 |

| UHS Surgical Ser | 21.30 | 21.30 | 21.30 |

| Integra York PA, | 19.88 | 19.88 | 19.88 |

| Milliken Healthc | 19.42 | 19.42 | 19.42 |

| Braemar Manufact | 18.51 | 18.51 | 18.51 |

| LifeScan, Inc. | 18.13 | 9.07 | 9.07 |

| American Medical | 16.83 | 16.83 | 16.83 |

| Duchesnay USA In | 16.29 | 16.29 | 16.29 |

| Ferring Pharmace | 16.07 | 16.07 | 16.07 |

| DENTSPLY IH Inc. | 16.06 | 16.06 | 16.06 |

| Celleration_Inc | 16.04 | 16.04 | 16.04 |

| Exelixis Inc. | 16.01 | 16.01 | 16.01 |

| Supernus Pharmac | 15.78 | 15.78 | 15.78 |

| EMD Serono, Inc. | 15.30 | 15.30 | 15.30 |

| Halozyme Inc | 14.48 | 14.48 | 14.48 |

| IsoTis OrthoBiol | 14.46 | 14.46 | 14.46 |

| Dentsply Interna | 13.92 | 13.92 | 13.92 |

| Endo Pharmaceuti | 13.55 | 13.55 | 13.55 |

| Medartis Inc. | 13.52 | 13.52 | 13.52 |

| Amarin Pharma In | 13.37 | 13.37 | 13.37 |

| Implant Direct I | 13.36 | 13.36 | 13.36 |

| Arbor Pharmaceut | 12.78 | 12.78 | 12.78 |

| Actelion Pharmac | 12.51 | 12.51 | 12.51 |

| Millennium Pharm | 12.45 | 12.45 | 12.45 |

| Orthofix Interna | 12.38 | 12.38 | 12.38 |

| Cornerstone Ther | 12.31 | 12.31 | 12.31 |

| Aerocrine, Inc | 12.27 | 12.27 | 12.27 |

| Universal Hospit | 12.03 | 12.03 | 12.03 |

| LeMaitre Vascula | 11.35 | 11.35 | 11.35 |

| Lundbeck LLC | 10.32 | 10.32 | 10.32 |

Distribution of Payments made to Plastic Surgery by Subspecialty

In the OPP data, a physician’s specialty is reported by the paying company and a physician is given the opportunity to verify the description of their specialty. As a result, if a physician was trained in a sub-specialty or has multiple specializations, he or she could have been reported as either specialty. For example, if a physician was trained as plastic surgeon and also completed a hand fellowship and a craniofacial fellowship, he or she could be reported as either: a plastic surgeon, a hand plastic surgeon or a craniofacial plastic surgeon. For this study, the largest payment that an individual was reported to receive in a particular specialty determined their specialty.

Payment Categories

OPP payments were reported under the following categories: consulting fees; food and beverage; honoraria; education; travel and lodging; entertainment; gifts; services other than consulting, including speaking at a venue other than a continuing education program (abbreviated as ‘speaker non-CEP’); and speaking for a non-accredited and non-certified, continuing education program (abbreviated as ‘speaker CEP’). The number of plastic surgeons that received payments for each payment category was quantified. Payment categories were also evaluated by non-academic versus academic plastic surgeons.

Association between H-index and industry payments

To explore whether plastic surgeons’ academic productivity was associated with the amount of payments received, we ascertained each plastics surgeon’s h-index by an automated Scopus search on December 15, 2014, which included publications since 1995. Introduced by Hirsh in 2005, the h-index is calculated by determining the number of papers, h, from a researcher with citation counts of h or greater for each paper (13). In order for a plastics surgeon’s h-index to be included in this study, the first name, last name, city and state as published in Scopus needed to be identical to that published in the OPP. There were a total of 1,286 h-indices of plastic surgeons which met these criteria. We calculated the total amount received by each physician and modeled the relative risk of a physician’s receiving $1000 or more in total payments using Poisson regression with a robust variance estimator (14).

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed with Stata 14.0/MP for Linux (College Station, Texas). We used the Wilcoxon rank-sum test to study payment differences among the various plastic surgery subspecialties as well among private practice and academic plastic surgeons. 95% Confidence intervals are reported as per the methods of Louis and Zeger (15).

RESULTS

Payments Made to All Healthcare Providers

During this first OPP reporting period, industry made payments totaling $508,215,270 to 359,402 HCPs. Total payments per HCP were: median (IQR) of $95 ($29–$258), with a mean of $1,414; the top 4 received $7,356,000, $3,994,022, $3,921,410 and $3,849,711 during the 5 month OPP study period.

Payments to Plastic Surgeons

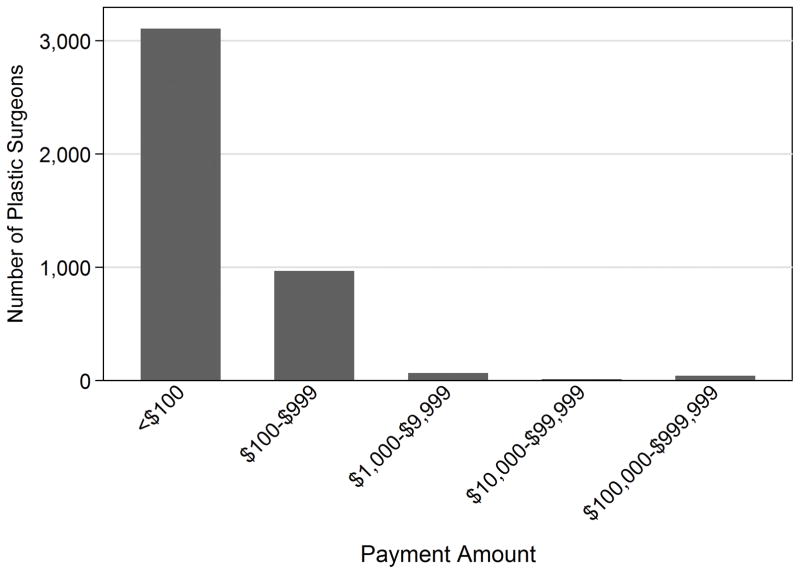

Our query of the OPP database identified a total of 4,195 plastic surgeons that received a total of $5,278,613. Plastic surgeons represent 1.17% of the all HCPs listed in the OPP and received 1% of the total payment amount in the OPP. Median (IQR) payment per plastic surgeon was $115 ($35–$298) with a mean of $1,258; the 4 highest payments were $341,384, $103,237, $96,541, and $81,659. Of plastic surgeons who received industry payments, 45.8% received <$100, 40.6% received payments between $100 and $999, 11% received between $1,000 and $9,999, 2.5% received between $10,000–$99,999, and 0.05% in excess of $100,000 (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Figure 1A: Payments Received per Plastic Surgeon by Amount Category

Among plastic surgeons, who received industry payments in the OPP, 45.8% received payments below $100, 40.6% received payments between $100 and $999, 11% received payments between $1,000 and $9,999, and 2.5% received payments between $10,000–$99,999, and 0.05% in excess of $100,000.

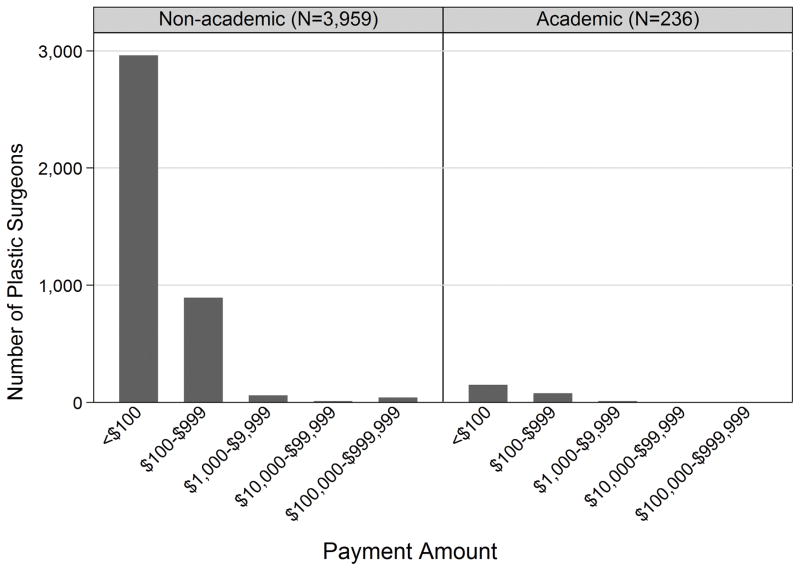

Figure 1B: Payments Received by Academic versus Non-Academic Plastic Surgeons

Non-academic plastic surgeons were paid more than academic plastic surgeons. The median (IQR) of payments to non-academic plastic surgeons was $165 ($81–$ 441) compared to $112 ($33–$291) for academic plastic surgeons (p<0.001). Among non-academic (N=3,959) plastic surgeons who received industry payments, 47% (N=1,846) received <$100, 40% (N=1,584) received payments between $100 and $999, 11% (N=439) received between $1,000 and $9,999, 2% (N=89) received between $10,000 and $99,999, and <0.1% (N=1) received more than $100,000. Among academic plastic surgeons (N=236) who received industry payments, 32% (N=77) received <$100, 51% (N=121) received payments between $100 and $999, 9% (N=21) received between $1,000 and $9,999, 7% (N=16) received between $10,000 and $99,999, and 0.4% received more than $100,000.

Payments between Academic versus Non-Academic Plastic Surgeons

In the OPP database there were 3,959 non-academic and 236 academic plastics surgeons. The median (IQR) of payments to non-academic plastic surgeons was $165($81–$ 441) compared to $112($33–$291) for academic plastic surgeons (p<0.001). Among non-academic (N=3,959) plastic surgeons who received industry payments, 47% (N=1,846) received <$100, 40% (N=1,584) received payments between $100 and $999, 11% (N=439) received between $1,000 and $9,999, 2% (N=89) received between $10,000 and $99,999, and <0.1% (N=1) received more than $100,000. Among academic plastic surgeons (N=236) who received industry payments, 32% (N=77) received <$100, 51% (N=121) received payments between $100 and $999, 9% (N=21) received between $1,000 and $9,999, 7% (N=16) received between $10,000 and $99,999, and 0.4% received more than $100,000 (Figure 1B).

Payments to Plastic Surgery by Subspecialty

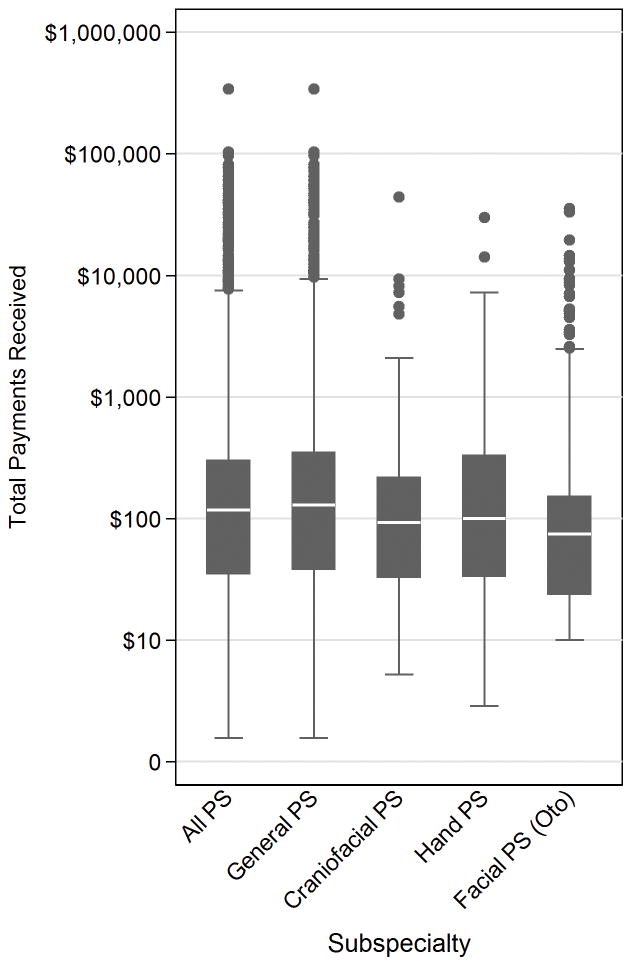

Of the 4,195 plastic surgeons, general plastic surgeons (N=3,261) received a total of $4,728,614, median (IQR) $128 ($37–$345), plastic surgeons specializing in craniofacial surgery (N=112) received a total of $108,437, median (IQR) $93 ($32–$218), plastics surgeons specializing in hand surgery (N=129) received a total of $102,721, median (IQR) $100 ($33–$331), and otolaryngologists specializing on in facial plastic surgery (Oto) (N=693) received a total of $338,839, median (IQR) $75 (23–$152, Table 1, Figure 2).

Table 1.

Payments by Plastic Surgery Subspecialty

| Plastics Surgery Sub-specialty | Total Payment | Median (IQR) | Mean | Number of Surgeons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plastic Surgery(General) | $4,728,614 | $128(37–345) | $1,450 | 3,261 |

| Craniofacial | $108,437 | $93 (32–218) | $968 | 112 |

| Hand | $102,721 | $100 (33–331) | $762 | 129 |

| Oto | $338,839 | $74 (23–152) | $488 | 693 |

| All Plastic Surgeons | $5,278,613 | $115 (34–298) | $1,258 | 4,195 |

Of the 4,195 plastic surgeons, general plastic surgeons (N=3,261) received a total of $4,728,614, median (IQR) $128 (37–345), plastic surgeons specializing in craniofacial surgery (N=112) received a total of $108,437, median (IQR) $93 (32–218), plastics surgeons specializing in hand surgery (N=129) received a total of $102,721, median (IQR) $100 (33–331), and otolaryngologists specializing in facial plastic surgery (Oto, N=693) received a total of $338,839, median (IQR) $75 (23–152).

Figure 2. Payments by Plastic Surgery Subspecialty.

Of the 4,195 plastic surgeons, general plastic surgeons (N=3,261) received a total of $4,728,614, median (IQR) $128 (37–345), plastic surgeons specializing in craniofacial (N=112) received a total of $108,437, median (IQR) $93 (32–218), plastics surgeons specializing in hand (N=129) received a total of $102,721, median (IQR) $100 (33–331), and otolaryngologists specializing on in facial plastic surgery (N=693) received a total of $338,839, median (IQR) $75 (23–152). Among all specialties Otolaryngologist specializing in facial plastic surgery received lower payments than any on the other specialties (p<0.01). There was no statistically significant difference among the general plastic surgery and other plastic surgery subspecialties.

Payment Categories

The $5,278,613 total payments made to plastic surgeons were categorized by the OPP as follows: $1,709,930 (32%) for speaker non-CEP; $ 1,403,770 (27%) for consulting fees; $ 767,003(15%) for travel and lodging; $702,340 (13%) for food and beverage; $305,030 (5.6%) for gifts; $215,651 (4%) for royalty; $96,806 (1.8%) for honoraria; $50,211 (0.9%) for education; 23,950 (0.4%) for speaker CEP; $2,131 (0.04%) for grants; and $1,792 (0.03%) for entertainment (Table 2).

Table 2.

Industry Payments by Category

| Payment Category | Total Payment (%) | Median (IQR) of Payments by category event | Number of payments by category | Median (IQR) of Payments by Surgeon | Number of Surgeons Paid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Speaker non-CEP | $1,709,930(32%) | $5,847 ($3000–$21,427) | 378 | $5,847 ($3,000–$18,728) | 131 |

| Consulting | $1,403,770(27%) | $2,100 ($750–$4,400) | 382 | $3,000 ($625–$7,033) | 181 |

| Travel & Lodging | $767,003(15%) | $ 228($109–$475) | 1,863 | $892 ($546–$1,407) | 490 |

| Food & Beverage | $702,340 (13%) | $ 102 ($31–114$) | 14,270 | $100 ($31–$211) | 4011 |

| Gift | $305,030(5.6%) | $575 ($275–$700) | 558 | $750 ($308–$1,500) | 273 |

| Royalty | $215,651(4%) | $3,588 ($693–$ 21,280) | 17 | $8,918 ($916–$50,825) | 9 |

| Honoraria | $96,806(1.8%) | $1,350($500–$3,000) | 46 | $1,500($550–$4,000) | 30 |

| Education | $50,211(0.9%) | $20 ($14–$79) | 215 | $24 ($14–$75) | 191 |

| Speaker CEP | $23,950(0.4%) | $900 ($500–$2,000) | 18 | $1,750 ($550–$2,500) | 12 |

| Grant | $2,131(0.04%) | $1065 ($131–$200) | 2 | $1065 ($131–$2,000) | 2 |

| Entertainment | $1,792(0.03%) | $99 ($94–$143) | 9 | $99 ($89–$143) | 9 |

| Total | $5,278,613 | $27 ($14–$122) | 17,758 | $131($38–$418) | 5,339 |

This table describes the amount paid to all plastic surgeons by payment category, the median (IQR) of each payments, the number of payments made by category. The median payments made to an individual plastic surgeon and the number of plastic surgeons that received payments in that category.

The median (IQR) for each payment made to an individual plastic surgeon and the percentage of plastic surgeons paid by expense category were: speaker non-CEP $5,847 ($3,000–$18,728) to 3% (N=131); $3,000 ($625–$7,033) consulting fees to 4% (N=181); travel and lodging $ 892 ($546–$1,407) to 10% (N=490); food and beverage $ 100 ($31–$211) to 95% (N=4011); gifts $750 ($308–$1,500)to 7% (N=273); royalty fees $8,918 ($916–$50,825) to <1% (N=9); honoraria $ 1,500($550–$4,000) to <1% (N=30); education $24 ($14–$75) to 5% (N=191); speaker CEP $ 1,750 ($550–$2,500) to <1% (N=12); grants $1065 ($131–$2,000) to <1% (N=2); and entertainment expenses $ 99 ($89–$143)to <1% (N=9, Table 2).

When comparing the percentage of non-academic versus academic plastic surgeons by payment categories, there were a greater percentage of academic surgeons that received payments for consulting (8.5% versus 4%) and honoraria (2.1% versus 0.6%). These results were not statistically significant. The results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Industry Payments by Non-Academic vs Academic Plastic Surgeons

| Non Academic Plastic Surgeons (N=3,959) | Academic Plastic Surgeons (N=236) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Payment Category | Total Payment (%) | Median (IQR) of Payments by Surgeon | Number of Surgeons Paid | Total Payment (%) | Median (IQR) of Payments by Surgeon | Number of Surgeons Paid |

| Speaker non-CEP | $1,432,713 (32%) | $5,100 (3,000–18,728) | 119 (3%) | $277,217 (36.3%) | $21,919 (5,616–26,975) | 12 (5%) |

| Consulting | 1208692 (26.8%) | $3,000 (500–7,000) | 161 (4%) | $195,078 (25.6%) | $4,100 (646–9,098) | 20 (8.5%) |

| Travel & Lodging | $625731 (13.9%) | $884 (544–1,373) | 447 (11.3%) | $141,271 (18.5%) | $971 ($546–$5,026) | 43 (18.2%) |

| Food & Beverage | $645,554 (14.3%) | $97 (30–204) | 3,781 (95.5%) | $56,785 (7.44%) | $150 (75–272) | 230 (97.5%) |

| Gift | $305,030 (5.6%) | $750 (308–1,500) | 273 (6.9%) | - | - | - |

| Royalty | $ 145387 (4%) | $8244 (219–50,825) | 7 (0.2%) | $70,264 (9.2%) | $35,132 (14,894–55,370) | 2 (0.8%) |

| Honoraria | $76,441 (1.7%) | $1500 (550–3,688) | 25 (0.6%) | $20,366 (2.6%) | $1,000 (1,000–7,866) | 5 (2.1%) |

| Education | $49,878 (0.1%) | $23 (14–75) | 187 (4.7%) | $333 (0.04%) | $65 (27–139) | 4 (1.7%) |

| Speaker CEP | $ 23,400 (0.5%) | $1,750 (550–2,500) | 11 (0.3%) | $550 (0.07%) | $550 | 1 (0.4%) |

| Grant | $2,131 (0.4%) | $1065 (131–2,000) | 2 (0.05%) | - | - | - |

| Entertainment | $815 (0.02%) | $99 (83–124) | 8 (0.002%) | $971 (0.13%) | $971 | 1 (0.4%) |

This table describes the amount paid to non-academic versus academic plastic surgeons by payment category, the total payment, the median (IQR) of payments received per surgeon and the number of surgeons paid in each category.

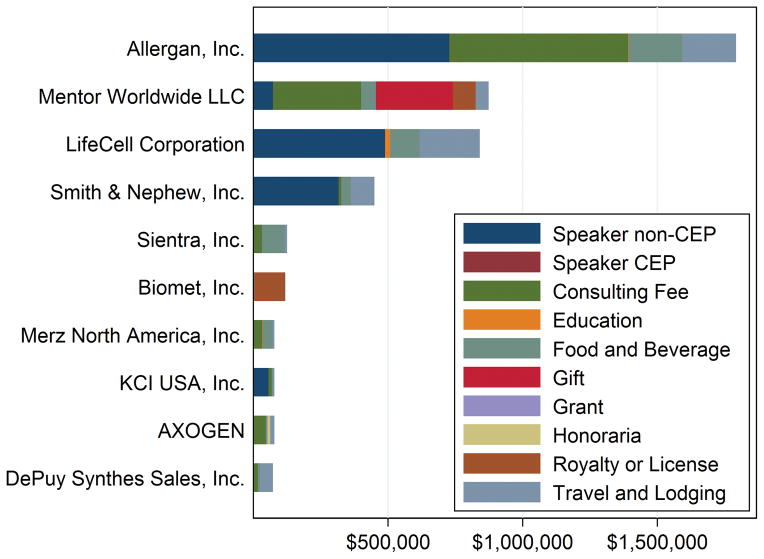

Distributions of Payments made by Companies

The total payment made by a single company to plastic surgeons ranged from $10.32 to $1,792,491. Of 216 companies that made payments to plastic surgeons (Appendix 1), the 10 highest paying companies accounted for $4,505,331 (85.4%) of the total payments. The three highest paying companies were: Allergan Inc., Mentor Worldwide, and LifeCell Corporation; they collectively contributed $3,507,157 (66.4%) of all payments. The distribution of payments by category from these 10 companies is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Category Payments of the Top 10 Companies.

These are the 10 companies that were identified to have the highest total amount payments made to plastic surgeons.

Geographic Distribution

In terms of total payments to plastic surgeons in a given state, the top 5 states were California ($669,739), Michigan ($576,992), Texas ($491,750), Florida ($478,849), and New York ($386,779). The 5 lowest states were: Wyoming ($161), Virginia ($314), Alabama ($644), Arkansas ($755) and South Dakota ($849). In terms of average payment-per-surgeon, the highest 5 states were Indiana ($3,701/surgeon), Michigan ($2,958/surgeon), Minnesota ($2,927/surgeon), Maryland ($2,531/surgeon) and Washington DC ($2,475/surgeon). The lowest 5 states were: Alabama ($46/surgeon), South Dakota ($84), Wisconsin ($121/surgeon), Colorado ($136/surgeon) and North Dakota ($138/surgeon, Figure 4A and B).

Figure 4.

Figure 4A: Total Payments made to Plastic Surgeons by State

The highest 5 states were California ($669,739), Michigan ($576,992), Texas ($491,750), Florida ($478,849), and New York ($386779). The 5 lowest states were: Wyoming ($161), Virginia ($314), Alabama ($644), Arkansas ($755) and South Dakota ($849).

Figure 4B: Average Payments/Surgeon by State

In terms of average payment-per-surgeon, the highest 5 states were Indiana ($3,701/surgeon), Michigan ($2,958/surgeon), Minnesota ($2,927/surgeon), Maryland ($2,531/surgeon) and Washington DC ($2,475/surgeon). The lowest 5 states were: Alabama ($46/surgeon), South Dakota ($84), Wisconsin ($121/surgeon), Colorado ($136/surgeon) and North Dakota ($138/surgeon).

Payments by H-index

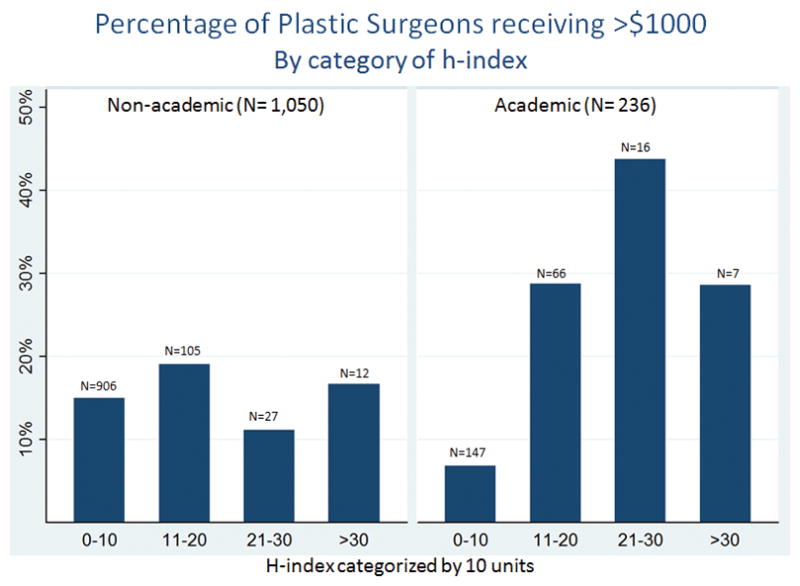

We were able to ascertain h-indices for 1286 plastic surgeons who published articles that would qualify for h-index calculation. The median (IQR) h-index was 4 (2–8). Of these, 1,053 plastic surgeons had a h-index of less than 10; 171 had a h-index between 11 and 20; 43 had a h-index between 21 to 30; and 19 had a h-index above 30. An increase of ten units of h-index was associated with a 29% higher chance of at least $1000 in total payments (RR = 1.131.291.48, p<0.001). In other words, if plastic surgeons with a h-index of 16 had a 29% higher chance of receiving at least $1,000 compared to a plastic surgeon with an h-index of 6. Among academic plastic surgeons, an increase in ten units of h-index was associated with a 77% higher chance of an academic plastic surgeon receiving at least $1000 in total payments (RR=1.47 1.772.11, p<0.001). Among non-academic plastic surgeons this association was not statistically significant (RR=0.89 1.09 1.32, p=0.4, Figure 5).

Figure 5. The Association of Payments made to Plastic Surgeons and their h-index.

An increase of ten units of h-index was associated with 77% higher chance of an academic plastic surgeon receiving at least $1000 in total payments (RR=1.47 1.772.11, p<0.001). For non-academic plastic surgeons this association was not statistically significant (RR=0.89 1.09 1.32, p<0.39).

DISCUSSION

The recent implementation of the Physician Payment Sunshine Act allows, for the first time, the characterization of current physician-industry relationships at a national level. The results from this study demonstrate that a total of $5,278,613 was paid to 4,195 plastic surgeons over a five month period. The median payment to plastic surgeons was $115 which in comparison, is within the range of other medical specialties in the OPP: $102 to dermatologists; $88 to neurosurgeons; and $173 to urologists (11). Amongst payment categories, the largest amount was paid for serving as a member of a non-CEP speaker bureau (32%) followed by consulting fees (27%). Additionally, industry payments to surgeons in private practice were higher than payments to academic plastic surgeons (median $165 versus median $112, p<0.001). Among academic plastic surgeons, an increase of 10 units of h-index was associated with a 77% higher chance of receiving at least $1000 in total payments (RR=1.47 1.772.11, p<0.001). This association was not seen among plastic surgeons in private practice (RR=0.89 1.09 1.32, p=0.4).

Under the Affordable Care Act (section 6002), the PPSA now mandates public reporting of payments to physicians by biomedical companies. Intended to bring greater transparency to the industry-physician landscape, the PPSA constitutes the first nationwide effort to shed light on the financial interactions between physicians and industry (1–3). The PPSA now requires all biomedical companies to report all “transfers of value” to physicians or teachings hospitals, including but not limited to, speaking and consulting fees, non-research grants, gifts, royalties, and investment interests. Given the recognized importance of biomedical industry’s support for research and innovation, CMS has designated a different track for disclosures of research funding and these transactions were not analyzed in this study (16).

A large body of literature has previously explored the effects of financial COIs on clinical care, research outcomes, and patient behavior (17–23). These studies suggest that although industry’s support for research, clinical care, and innovation is essential, its financial support brings the potential for undue influence (24–26). A recent study from our institution reported that financial COIs in breast reconstruction were associated with under-reporting of surgical complications when an industry-marketed product, Acellular Dermal Matrix (ADM), was utilized by the surgeon-researchers (27). DeGeorge et al made similar observations in abdominal wall reconstruction (28). In light of such findings, the OPP data is a means to provide healthcare consumers information on the types of financial relationships that may exist between biomedical companies and their physicians, in hopes of deterring potentially detrimental relationships between industry and physicians.

In our study, we demonstrate that scientific productivity, in increments of 10 units of h-index, was strongly associated with higher industry payments for academic plastic surgeons. A 10 unit increase, on average, was shown to be the difference between full professors and assistant professors in plastic surgery residency training programs (29–32). The driver behind the strong association between having a higher h-index and receiving greater payments from industry is unknown. However, it may suggest that biomedical companies preferentially recruit and pay scientifically productive academic surgeons for their expertise, reputation and knowledge. Future studies should examine this association more closely and account for other factors that may be driving this potentially important association.

The lack of an association between h-index and payment amount among private-practice plastic surgeons suggests that in private practice, industry may value other factors than academic productivity when establishing financial relationships. These factors may include seniority, years in practice, surgical volume, or good entrepreneurship skills. Future studies will be needed to explore these associations further. Furthermore, our analysis shows that private-practice plastic surgeons were on average paid greater amounts by industry compared to academic-practice plastic surgeons. Although our study did not explore the drivers behind this specific finding, future studies are needed to determine what variables are associated with higher payments in private-practice plastic surgeons. Lastly, our analysis demonstrated that consulting and non-CEP speaker fees, commonly known as “Speaker Bureaus membership fees” made up the largest category of expenditures. Although it is still unclear whether all types of COI have similar effects on clinical care or research outcomes, recent studies in the literature suggest that patients view consultancy fees more favorably than other financial relationships with industry since they consider consultant-physicians as experts and “key opinion leaders” (KOLs) in their field (33, 34).

Our study has several limitations which merit consideration. Many have raised concerns with the implementation and documentation of the OPP database since the OPP data was subjected to limited pre-release vetting (1). However, this limitation will be partially addressed as the PPSA evolves over time and it improves on previous deficiencies. Additionally, academic productivity was measured by utilizing the h-index. Although the efficacy of the h-index in assessing academic productivity has been validated in several medical specialties, including plastic surgery (30, 32, 35), it has several limitations which are beyond the discussion of this paper. Moreover, the availability of OPP data is limited to a 5-month reporting period, which may not give a true picture of the entire physician-industry financial landscape. However, this limitation will be further addressed as future iterations of the database release annual data, and similar studies to ours continue to report on preliminary OPP database findings (11, 36, 37).

A free market is most efficient when consumers make informed decisions. The primary goal of the PPSA is to “permit patients to make better informed decision when choosing healthcare professionals and making treatment decisions” (34). Although the true value of the OPP database remains unclear, CMS projects that the OPP will undoubtedly drive physicians and industry to better self-regulation. As our federal government embraces disclosures, it is yet to be determined how full transparency will change the physician-industry complex.

Abbreviations

- ADM

Acellular Dermal Matrix

- CEP

Continuing Education Program

- CME

Continuing Medical Education

- CMS

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- COI

Conflicts of Interest

- OTO

Otolaryngologist specializing in facial plastic surgery

- HCP

Health Care Provider

- HRSA

Health Resources and Services Administration

- IQR

Interquartile Range

- KOL

Key Opinion Leaders

- OPP

Open Payments Program

- PPSA

Physician Payment Sunshine Act

Bibliography

- 1.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Service. [Accessed January, 2015];The Open Payments Database [ web site] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agrawal S, Brennan N, Budetti P. The Sunshine Act--effects on physicians. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2054–2057. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1303523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenthal MB, Mello MM. Sunlight as disinfectant--new rules on disclosure of industry payments to physicians. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2052–2054. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1305090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wazana A. Physicians and the pharmaceutical industry: is a gift ever just a gift? JAMA. 2000;283:373–380. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brennan TA, et al. Health industry practices that create conflicts of interest: a policy proposal for academic medical centers. JAMA. 2006;295:429–433. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.4.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gagnon MA, Lexchin J. The cost of pushing pills: a new estimate of pharmaceutical promotion expenditures in the United States. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e1. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell EG, et al. A national survey of physician-industry relationships. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1742–1750. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riskin DJ, et al. Innovation in surgery: a historical perspective. Ann Surg. 2006;244:686–693. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000242706.91771.ce. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y, Kotsis SV, Chung KC. Applying the concepts of innovation strategies to plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132:483–490. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182958c9a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmed R, et al. Where the Sun Shines: Industry’s Payments to Transplant Surgeons. Am J Transplant. 2016 Jan;16(1):292–300. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang JS. The Physician Payments Sunshine Act: data evaluation regarding payments to ophthalmologists. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:656–661. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rathi VK, Samuel AM, Mehra S. Industry ties in otolaryngology: initial insights from the physician payment sunshine act. Otolaryngology Head Neck Surg. 2015 Jun;152(6):993–3. doi: 10.1177/0194599815573718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirsch JE. An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16569–16572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507655102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Louis TA, Zeger SL. Effective communication of standard errors and confidence intervals. Biostatistics. 2009;10:1–2. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxn014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorlach I, Pham-Kanter G. Brightening up: the effect of the Physician Payment Sunshine Act on existing regulation of pharmaceutical marketing. J Law Med Ethics. 2013;41:315–322. doi: 10.1111/jlme.12022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs of the American Medical Association. Guidelines on gifts to physicians from industry: an update. Food Drug Law J. 2001;56:27–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chren MM, Landefeld CS, Murray TH. Doctors, drug companies, and gifts. JAMA. 1989;262:3448–3451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaughnessy AF. Drug promotion in a family medicine training center. JAMA. 1988;260:926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaughnessy AF, Slawson DC, Bennett JH. Separating the wheat from the chaff: identifying fallacies in pharmaceutical promotion. J Gen Intern Med. 1994;9:563–568. doi: 10.1007/BF02599283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhandari M, et al. Association between industry funding and statistically significant pro-industry findings in medical and surgical randomized trials. CMAJ. 2004;170:477–480. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown A, et al. Association of industry sponsorship to published outcomes in gastrointestinal clinical research. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1445–1451. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campbell EG, Louis KS, Blumenthal D. Looking a gift horse in the mouth: corporate gifts supporting life sciences research. JAMA. 1998;279:995–999. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.13.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carragee EJ, et al. A challenge to integrity in spine publications: years of living dangerously with the promotion of bone growth factors. Spine J. 2011;11:463–468. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carragee EJ, Hurwitz EL, Weiner BK. A critical review of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 trials in spinal surgery: emerging safety concerns and lessons learned. Spine J. 2011;11:471–491. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2011.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gelberman RH, et al. Orthopaedic surgeons and the medical device industry: the threat to scientific integrity and the public trust. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:765–777. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lopez J, et al. The impact of conflicts of interest in plastic surgery: an analysis of acellular dermal matrix, implant-based breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133:1328–1334. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DeGeorge BR, Jr, Holland MC, Drake DB. The impact of conflict of interest in abdominal wall reconstruction with acellular dermal matrix. Ann Plast Surg. 2015;74:242–247. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000000372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Therattil PJ, et al. Application of the h-Index in Academic Plastic Surgery. Ann Plast Surg. 2014 doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000000382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gast KM, Kuzon WM, Jr, Waljee JF. Bibliometric indices and academic promotion within plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134:838e–844e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gast KM, et al. Influence of training institution on academic affiliation and productivity among plastic surgery faculty in the United States. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134:570–578. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Susarla SM, et al. Do quantitative measures of academic productivity predict academic rank in plastic surgery? A national study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015 doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000001531. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khan MH, et al. The surgeon as a consultant for medical device manufacturers: what do our patients think? Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:2616–8. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318158cc3a. discussion 2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steinbrook R. Public disclosure of Medicare payments to individual physicians. JAMA. 2014;311:1285–1286. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Therattil PJ, et al. Application of the h-Index in Academic Plastic Surgery. Ann Plast Surg. 2014 doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000000382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rathi VK, Samuel AM, Mehra S. Industry Ties in Otolaryngology: Initial Insights from the Physician Payment Sunshine Act. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015 doi: 10.1177/0194599815573718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Samuel AM, et al. Orthopaedic Surgeons Receive the Most Industry Payments to Physicians but Large Disparities are Seen in Sunshine Act Data. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4413-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]