Abstract

The Kindlin protein family, comprising Kindlin-1, Kindlin-2 and Kindlin-3, play important roles in various human cancers. Here, to explore the clinical significance of Kindlins in human osteosarcomas, quantitative real-time PCR and Western blot analyses were performed to detect the expression of Kindlin-1, Kindlin-2 and Kindlin-3 mRNAs and proteins in 20 self-pairs of osteosarcoma and adjacent noncancerous tissues. Then, immunohistochemistry was performed to examine subcellular localizations and expression patterns of Kindlin proteins in 100 osteosarcoma and matched adjacent noncancerous tissues. Kindlin-1, Kindlin-2 and Kindlin-3 protein immunostainings were localized in the cytoplasm, nucleus and cytoplasm, respectively, of tumor cells in primary osteosarcoma tissues. Statistically, the expression levels of Kindlin-1 and Kindlin-2 mRNAs and proteins in osteosarcoma tissues were all significantly higher (both P<0.01), but those of Kindlin-3 mRNA and protein were both dramatically lower (both P<0.05), than in matched adjacent noncancerous tissues. In addition, the overexpressions of Kindlin-1 and Kindlin-2 proteins were both significantly associated with high tumor grade (both P=0.01), presence of metastasis (both P=0.006), recurrence (both P=0.006) and poor response to chemotherapy (both P=0.02). Moreover, Kindlin-1 and Kindlin-2 expressions were both identified as independent prognostic factors for overall (both P=0.01) and disease-free (P=0.02 and 0.01, respectively) survivals of osteosarcoma patients. However, no associations were observed between Kindlin-3 expression and various clinicopathologic features and patients’ prognosis. In conclusion, aberrant expression of Kindlin-1 and Kindlin-2 may function as reliable markers for progression and prognosis in osteosarcoma patients, especially for tumor recurrence.

Keywords: osteosarcoma, Kindlin protein family, clinicopathologic feature, overall survival, disease-free survival

Introduction

Osteosarcoma, one of the most malignant and common solid tumors predominantly occurring around regions with active bone growth and repair, is characterized by rapid growth rate, high local aggressiveness and early metastasis to distant bones and the lungs.1 Its incidence peaks in children and adolescents.2 Despite great improvements made in surgical technology, neoadjuvant chemotherapy and combined therapeutic strategies, the 5-year survival rate is only at 20% in osteosarcoma patients with tumor metastasis and 15% for patients with more than five pulmonary metastatic lesions.3 Recently, accumulating studies have investigated the underlying molecular and pathological mechanisms of the occurrence, progression and metastasis of osteosarcoma.4 In our previous studies, we demonstrated that the deregulation of three miRNA/mRNA combinations, including miR-128/target gene PTEN, miR-223/target gene epithelial cell transforming sequence 2, and miR-183/target gene Ezrin axes, were significantly associated with the aggressive progression of human osteosarcoma.5–7 More interestingly, these combinations may function as potential prognostic markers for patients with this malignancy.5–7 However, the exact mechanisms of this malignancy remain unclear, thereby posing great challenges to its clinical treatment. Thus, it is necessary to identify new markers for early diagnosis and prognosis in patients with osteosarcomas to explore the complex mechanisms and to develop more efficient tumor-targeted therapeutic strategies.

The Kindlin protein family, comprising three members, Kindlin-1, Kindlin-2 and Kindlin-3, that are evolutionarily conserved focal adhesion proteins, function as crucial regulatory components of cell–extracellular matrix junctions, which are involved in cell adhesion, proliferation, differentiation and motility.8,9 Kindlin-1, Kindlin-2 and Kindlin-3 are, respectively, encoded by Fermitin family member 1 (FERMT1, chromosome 20p12.3), FERMT2 (chromosome 14q22.1) and FERMT3 (chromosome 11q13.1), and are all featured by a C-terminal FERM (4.1 protein, ezrin, radixin and moesin) domain bisected by a pleckstrin-homology domain.8 Under normal conditions, Kindlin-1 is predominantly expressed in epithelial cells, such as keratinocytes and intestinal epithelial cells; Kindlin-2 is found ubiquitously, but is absent in all blood cells; and Kindlin-3 is broadly expressed in hematopoietic cells and, possibly, also at low levels in endothelial cells.9 Pathologically, the dysregulation of Kindlins has been observed in various malignant tumor cells and has been reported to be implicated in tumorigenesis and tumor progression. For example, the aberrant expression of Kindlin-1 in breast cancer, lung cancer, pancreatic cancer and colorectal cancer may enhance cell adhesion, proliferation and motility;10–13 Kindlin-2 may exert various oncogenic roles in promoting tumor invasion by activating Wnt signaling or silencing the microRNA-200 family;14 and Kindlin-3 has been found to be downregulated in melanoma, breast cancer, lung cancer and kidney cancer, suggesting that it may play a role in controlling the malignant phenotypes of these cancers.15–18 However, the involvement of Kindlin-1, Kindlin-2 and Kindlin-3 in human osteosarcoma remains unclear.

To address this problem, we here performed quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR), Western blot and immunohistochemistry to detect the expression patterns of Kindlins, at both mRNA and protein levels, in osteosarcoma and noncancerous bone tissues collected from patients with primary osteosarcomas. Then, the associations of their expression levels with various clinicopathologic features and patients’ prognosis were statistically evaluated.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical, the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region and the People’s Hospital of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China. Prior to surgery, all patients provided written informed consent for inclusion in this study.

Patients and tissue samples

For quantitative real-time PCR and Western blot analyses, 20 self-pairs of fresh osteosarcoma and adjacent noncancerous tissues were obtained from 20 patients with primary osteosarcomas, who underwent surgical operations at the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical, the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region and the People’s Hospital of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region between 2014 and 2015. This cohort included 12 males and 8 females, and they were aged from 12 to 28 years (mean age was 18.2). All samples were immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen or stored at −80°C before quantitative real-time PCR and Western blot analyses.

For immunohistochemistry, a total of 100 primary osteosarcoma patients, who underwent surgical operations at the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical, the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region and the People’s Hospital of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region between 2005 and 2009, were enrolled in the present study. This cohort included 68 males and 32 females, and they were aged from 10 to 28 years (mean age was 18.1). One hundred self-pairs of osteosarcoma and the corresponding noncancerous bone tissue samples were collected from these patients.

For enrollment of all patients in this study, the inclusion criteria were provided as following: 1) with malignant osteosarcomas in the limb; 2) after establishing the diagnosis, all patients were treated with the same neoadjuvant chemotherapy consisting of methotrexate, doxorubicin, cisplatin and ifosfamide; 3) demographic information (including age and sex) and clinicopathologic data (including tumor site, histologic type, tumor grade, metastasis and recurrence status, and response to preoperative chemotherapy) were collected. Histopathologic diagnosis of all specimens was confirmed by two trained pathologists. All drugs were given intravenously. Following neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the patients underwent wide resection of tumors. Response to chemotherapy was classified as “poor” (<90% tumor necrosis) and “good” (>90% tumor necrosis) through histologic analysis of tumor specimens after surgery.19 The clinicopathologic characteristics are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Association between the expression of Kindlin proteins and various clinicopathologic features of osteosarcoma patients

| Clinicopathologic features | No of cases, n (%) | Kindlin-1-high, n (%) | P-value | Kindlin-2-high, n (%) | P-value | Kindlin-3-high, n (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||||||

| <18 | 40 (40.00) | 20 (50.00) | NS | 21 (52.50) | NS | 22 (55.00) | NS |

| ≤18 | 60 (60.00) | 32 (53.33) | 30 (47.50) | 28 (45.00) | |||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 68 (68.00) | 36 (52.94) | NS | 35 (51.47) | NS | 38 (55.88) | NS |

| Female | 32 (32.00) | 16 (47.06) | 16 (47.06) | 12 (44.12) | |||

| Tumor site | |||||||

| Femur | 55 (55.00) | 29 (52.73) | NS | 28 (50.91) | NS | 27 (49.09) | NS |

| Tibia | 20 (20.00) | 10 (50.00) | 11 (55.00) | 10 (50.00) | |||

| Humeral bone | 15 (15.00) | 8 (53.33) | 7 (46.67) | 8 (53.33) | |||

| Other | 10 (10.00) | 5 (50.00) | 5 (50.00) | 5 (50.00) | |||

| Histologic type | |||||||

| Osteoblastic | 55 (55.00) | 29 (52.73) | NS | 28 (50.91) | NS | 27 (49.09) | NS |

| Chondroblastic | 20 (20.00) | 10 (50.00) | 11 (55.00) | 10 (50.00) | |||

| Fibroblastic | 15 (15.00) | 8 (53.33) | 7 (46.67) | 8 (53.33) | |||

| Telangiectatic | 10 (10.00) | 5 (50.00) | 5 (50.00) | 5 (50.00) | |||

| Tumor grade | |||||||

| Low | 15 (15.00) | 3 (20.00) | 0.01 | 4 (26.67) | 0.01 | 6 (40.00) | NS |

| High | 85 (85.00) | 49 (57.64) | 47 (55.29) | 44 (51.76) | |||

| Metastasis | |||||||

| Absent | 60 (60.00) | 20 (33.33) | 0.006 | 21 (35.00) | 0.006 | 27 (45.00) | NS |

| Present | 40 (40.00) | 32 (80.00) | 30 (75.00) | 23 (57.50) | |||

| Recurrence | |||||||

| Absent | 70 (60.00) | 27 (38.57) | 0.006 | 28 (40.00) | 0.006 | 34 (48.57) | NS |

| Present | 30 (40.00) | 25 (83.33) | 23 (76.67) | 16 (53.33) | |||

| Response to preoperative chemotherapy | |||||||

| Good | 50 (50.00) | 19 (38.00) | 0.02 | 18 (36.00) | 0.02 | 21 (42.00) | NS |

| Poor | 50 (50.00) | 33 (66.00) | 33 (66.00) | 29 (58.00) | |||

Abbreviation: NS, not significant.

For survival analysis, all 100 osteosarcoma patients received follow-up. They were monitored with computed tomography (CT) performed every 3 months during the first 3 years after chemotherapy, every 4 months during years 4 and 5, and every 6 months thereafter. The development of local recurrence and distant metastasis were detected by CT scans or magnetic resonance imaging. The median follow-up was 29.82 months (range: 5.26–38.89 months). For survival analyses, overall survival was defined as the time interval from the date of diagnosis at our center to the date of death or the last follow-up. Disease-free survival was defined as the time interval from diagnosis at our center to progressive disease, death from any other cause than progression or a second primary cancer.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNAs in osteosarcoma and adjacent noncancerous tissues were extracted using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) based on the instructions to the users. RNAs were then reverse transcribed using the high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). After that, the quantitative PCR was performed using the SYBR-Green fluorescent dye method based on a Rotor Gene 3000 real-time PCR apparatus. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as an internal normalization control for Kindlin mRNAs. The primer sequences used in this study were listed as follows: for Kindlin-1, forward primer: 5′-TTGGGATTCAGGAAGACAGG-3′, reverse primer: 5′-CCCTGACCAGTTGGGATAGA-3′; for Kindlin-2, forward primer: 5′-TGTCCCCGCTATCTAAAAAA-3′, reverse primer: 5′-TGATGGGCCTCCAAGATTCT-3′; for Kindlin-3, forward primer: 5′-GGCATCGCCAACAACC-3′, reverse primer: 5′-CACTGGCGCATGTTGC-3′; for GAPDH, forward primer: 5′-AATCCCATCACCATCTTCCA-3′, reverse primer: 5′-TGGACTCCACGACGTACTCA-3′. The amplification specificity was checked by melting curve analysis. Relative expression of Kindlin mRNAs was calculated based on the 2−ΔΔCT method.

Western blot analysis

Total proteins of osteosarcoma and adjacent noncancerous tissues were extracted using radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride and were quantified by a BCA kit (Thermo, Waltham, MA, USA). Proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Then, the membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk (Bio-Rad) in Tris-buffered saline containing Tween 20 (TBST) solution, overnight at 4°C. After that, the following primary antibodies were used: Kindlin-1 (rabbit polyclonal antibody; Millipore, Billerica, CA, USA; 1:100 dilution), Kindlin-2 (rabbit polyclonal antibody, Millipore; 1:150 dilution), Kindlin-3 (rabbit polyclonal antibody; Abcam, MA, USA; 1:100 dilution) and GAPDH (rabbit polyclonal antibody, Abcam; 1:150 dilution). Secondary antibodies were incubated after washing with TBST at room temperature for 1 h (horse radish peroxidase labeled goat anti-mouse IgG, 1:1000; Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). The membranes were detected by ECL system (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA), and gray assay was performed by ImageQuant 5.2 software. GAPDH protein levels were used as a control to verify equal protein loading.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed to examine subcellular localizations and expression patterns of Kindlin proteins in osteosarcoma and noncancerous bone tissues. All fresh, resected tissue samples were fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin and cut into 4 μm-thick sections, which were subsequently dewaxed in xylene and rehydrated with graded alcohol. Following rinsing with distilled water, the antigen was incubated in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid buffer at 100°C for 20 min and then cooled to room temperature. The slides were then incubated at 4°C overnight with the primary antibodies: Kindlin-1 (rabbit polyclonal antibody, Millipore; 1:100 dilution), Kindlin-2 (rabbit polyclonal antibody, Millipore; 1:150 dilution) and Kindlin-3 (rabbit polyclonal antibody, Abcam; 1:100 dilution). After washing with phosphate-buffered solution (PBS) three times, the biotin-labeled secondary antibody was added and the sections were incubated at room temperature for 10 min. After washing with PBS three times, 3,3′-diaminobenzidine chromogenic reagents were added. Then, sections were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated and mounted. The negative controls were processed in a similar manner with PBS instead of the primary antibodies.

Evaluation of immunostaining results

The immunoreactive scores (IRSs) were evaluated by two independent pathologists who were blinded to the clinical information of osteosarcoma patients enrolled in the current study. The IRSs were calculated by integrating the proportion of positive cells and the intensity of immunoreactivity based on the description of the previous studies.20–22 The median value of the total IRSs was calculated and used as a cutoff point to divide all osteosarcoma patients into Kindlin-1-low/high, Kindlin-2-low/high or Kindlin-3-low/high groups.

Statistical analysis

All data in this study were statistically analyzed using the SPSS statistical package (version 11.0 for Windows; SPSS Inc, IL, USA). Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Differences of Kindlin mRNA and protein expression between osteosarcoma and corresponding noncancerous bone tissues were evaluated by the paired t-test. Associations between various clinicopathologic characteristics and Kindlin protein expression were analyzed by χ2 tests. Survival analyses were performed using the Kaplan–Meier and the log-rank tests. Differences were considered statistically significant when P-value was <0.05.

Results

Kindlin gene and protein expression levels in human osteosarcoma tissues

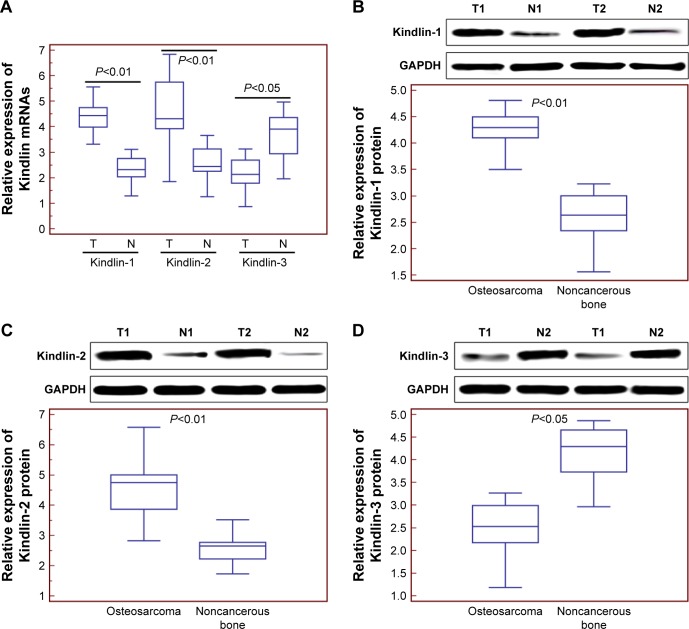

Compared with adjacent noncancerous tissues, the expression levels of Kindlin-1 and Kindlin-2 mRNAs were both significantly increased in osteosarcoma tissues (for Kindlin-1, tumor vs normal: 4.36±0.58 vs 2.34±0.53, P<0.01, Figure 1A; for Kindlin-2, tumor vs normal: 4.61±1.42 vs 2.59±0.68, P<0.01, Figure 1A), whereas the expression level of Kindlin-3 mRNA was markedly decreased in osteosarcoma tissues (tumor vs normal: 2.16±0.66 vs 3.71±0.90, P<0.05, Figure 1A). The changes in expression levels of Kindlin proteins in osteosarcoma and adjacent noncancerous tissues detected by Western blot analysis were similar to those at mRNA levels (Figure 1B–D).

Figure 1.

Kindlin gene and protein expression levels in human osteosarcoma tissues.

Notes: (A) Kindlin-1 and Kindlin-2 mRNA levels in osteosarcoma tissues were both significantly higher than those in adjacent noncancerous tissues (both P<0.01), whereas Kindlin-3 mRNA levels in osteosarcoma tissues were significantly lower than those in adjacent noncancerous tissues (P<0.05). (B) Kindlin-1 protein levels in osteosarcoma tissues were significantly higher than those in adjacent noncancerous tissues (P<0.01). (C) Kindlin-2 protein levels in osteosarcoma tissues were significantly higher than those in adjacent noncancerous tissues (P<0.01). (D) Kindlin-3 protein levels in osteosarcoma tissues were significantly lower than those in adjacent noncancerous tissues (P<0.01). The mRNA and protein levels of Kindlins were detected by quantitative real-time PCR and Western blot analyses. T and N refer to osteosarcoma and adjacent noncancerous tissues, respectively.

Abbreviations: GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

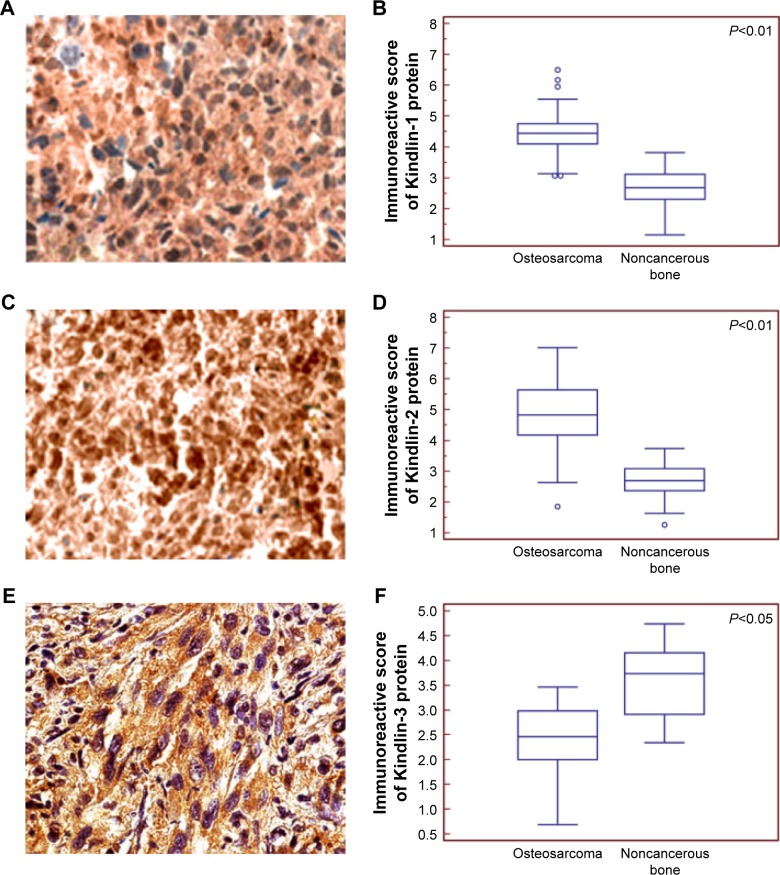

Subcellular localizations and expression patterns of Kindlin proteins in human osteosarcoma tissues

According to the results of immunochemistry analysis, the positive Kindlin-1 (Figure 2), Kindlin-2 (Figure 2C) and Kindlin-3 (Figure 2E) protein immunostainings were, respectively, localized in cytoplasm, nucleus, and cytoplasm of tumor cells in primary osteosarcoma tissues. Statistically, the expression levels of Kindlin-1 (tumor vs normal: 4.49±0.78 vs 2.69±0.59, P<0.01, Figure 2B) and Kindlin-2 (tumor vs normal: 4.89±1.16 vs 2.72±0.56, P<0.01, Figure 2D) proteins in osteosarcoma tissues were both significantly higher, but that of Kindlin-3 protein (tumor vs normal: 2.41±0.65 vs 3.37±0.83, P<0.05, Figure 2F) was dramatically lower than those in adjacent noncancerous tissues.

Figure 2.

Subcellular localizations and expression patterns of Kindlin proteins in human osteosarcoma tissues.

Notes: The positive Kindlin-1 (A) Kindlin-2 (C) and Kindlin-3 (E) protein immunostainings were localized in the cytoplasm, nucleus and cytoplasm, respectively, of tumor cells in primary osteosarcoma tissues. Statistically, the expression levels of Kindlin-1 (B) and Kindlin-2 (D) proteins in osteosarcoma tissues were both significantly higher, but that of Kindlin-3 protein (F) was dramatically lower than those in noncancerous bone tissues. The subcellular localizations and expression patterns of Kindlins were examined by immunohistochemistry.

In addition, the median values of Kindlin-1 (4.56), Kindlin-2 (4.56) and Kindlin-3 (3.10) protein expression levels in all osteosarcoma tissues were used as cutoff points to classify 100 patients with osteosarcomas into Kindlin-1-low (n=48), Kindlin-1-high (n=52), Kindlin-2-low (n=49), Kindlin-2-high (n=51), Kindlin-3-low (n=50) and Kindlin-3- high (n=50) expression groups.

Kindlin-1 and Kindlin-2 overexpression associated with aggressive clinicopathologic features of human osteosarcoma

As shown in Table 1, osteosarcoma patients with high Kindlin-1 expression or high Kindlin-2 expression more frequently had high tumor grade (both P=0.01), positive metastasis (both P=0.006) and recurrence (both P=0.006), and poor response to chemotherapy (both P=0.02). However, no associations were observed between Kindlin-3 expression and various clinicopathologic features.

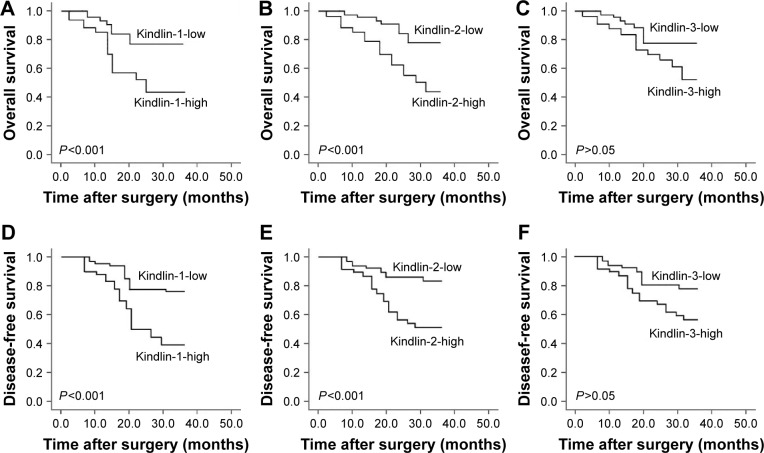

Kindlin-1 and Kindlin-2 overexpression predict poor prognosis in human osteosarcoma

All 100 osteosarcoma patients enrolled in this study received follow-up. The 3-year overall survival was 75.00% and the 3-year disease-free survival was 58.00% for all patients. According to the results of Kaplan–Meier and log-rank tests, both overall and disease-free survivals of osteosarcoma patients with high Kindlin-1 expression (Figure 3 both P<0.001) and high Kindlin-2 expression (Figure 3B and E, respectively; both P<0.001) were significantly shorter than those with low Kindlin-1 expression and low Kindlin-2 expression. However, there were no significant differences in both overall and disease-free survivals between high and low Kindlin-3 expression groups (P>0.05, Figure 3C and F).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier overall (A–C) and disease-free (D–F) survival curves for osteosarcoma patients based on Kindlin-1 (A and D), Kindlin-2 (B and E) and Kindlin-3 (C and F) protein expression.

Cox proportional hazard model confirmed that Kindlin-1 expression (for overall survival: relative risk [RR]: 7.21, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.06–15.38, P=0.01; for disease-free survival: RR: 7.86, 95% CI: 1.01–16.22, P=0.01), Kindlin-2 expression (for overall survival: RR: 6.89, 95% CI: 0.96–14.23, P=0.02; for disease-free survival: RR: 7.23, 95% CI: 1.01–15.39, P=0.01), response to preoperative chemotherapy (for overall survival: RR: 7.28, 95% CI: 1.08–15.11, P=0.01; for disease-free survival: RR: 8.25, 95% CI: 1.11–17.99, P=0.006) and metastasis status (for overall survival: RR: 6.44, 95% CI: 0.96–13.62, P=0.02; for disease-free survival: RR: 6.92, 95% CI: 1.00–14.06, P=0.01) were all independent prognostic factors of unfavorable survival in human osteosarcoma (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate survival analysis of overall and disease-free survivals in 100 patients with osteosarcomas

| Variables | Overall survival

|

Disease-free survival

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR (95% CI) | P-value | RR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Kindlin-1 expression | 7.21 (1.06–15.38) | 0.01 | 7.86 (1.01–16.22) | 0.01 |

| Kindlin-2 expression | 6.89 (0.96–14.23) | 0.02 | 7.23 (1.01–15.39) | 0.01 |

| Kindlin-3 expression | 4.06 (0.72–8.82) | NS | 4.19 (0.79–8.96) | NS |

| Tumor grade | 2.42 (0.61–5.16) | NS | 3.37 (0.70–7.38) | NS |

| Response to preoperative chemotherapy | 7.28 (1.08–15.11) | 0.01 | 8.25 (1.11–17.99) | 0.006 |

| Metastasis status | 6.44 (0.96–13.62) | 0.02 | 6.92 (1.00–14.06) | 0.01 |

| Recurrence status | 3.26 (0.68–7.02) | NS | 3.59 (0.71–7.83) | NS |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; NS, not significant; RR, relative risk.

Discussion

Identifying novel predictors for screening osteosarcoma patients with invasive potentials and poor prognosis is significantly crucial. In the current study, we conducted a hospital-based case study and first examined the expression patterns of three members of the Kindlin protein family. According to our immunohistochemical observations, quantitative real-time PCR and Western blot analysis, Kindlin-1, Kindlin-2 and Kindlin-3 proteins were, respectively, localized in cytoplasm, nucleus, and cytoplasm of tumor cells, and all were aberrantly expressed in primary osteosarcoma tissues compared with adjacent noncancerous controls. Second, the overexpressions of Kindlin-1 and Kindlin-2 proteins were both significantly associated with high tumor grade, presence of metastasis and recurrence, and poor response to chemotherapy. More interestingly, Kindlin-1 and Kindlin-2 expressions were both identified as independent prognostic factors for overall and disease-free survivals of osteosarcoma patients. However, no associations were observed between Kindlin-3 expression and various clinicopathologic features and patients’ prognosis.

Members of the Kindlin protein family function as the regulators for the activation of integrins, which have been reported to be transmembrane adhesion receptors and to play crucial roles in promoting fundamental developmental, physiological and pathological processes.8,9 Due to the links to integrin function, Kindlin proteins have attracted much attention in the research field of the cell–matrix adhesion and signaling community.8,9 Kindlin proteins, as evolutionarily conserved focal adhesion, all contain 4.1 protein, ezrin, radixin, moesin domain, which is responsible for their interactions with integrins and signal transduction, and pleckstrin homology domain.23 Kindlin proteins are observed to have different subcellular localizations.24 In tumor cells of human osteosarcoma tissues, our immunohistochemistry analysis confirmed for the first time that Kindlin-1 protein was diffusely present throughout the cytoplasm, Kindlin-2 was predominantly found in nucleus and Kindlin-3 was localized on the cytoplasm.

Different subcellular localizations imply that Kindlin proteins may exert various functions during cancer progression. Focal adhesion proteins, such as focal adhesion kinase and migfilin, have been reported to interact with Kindlin-1, which subsequently link integrins and signal pathways to reorganize the actin cytoskeletion and to be involved in carcinogenesis and cancer progression.25 Overexpression of Kindlin-1 at both mRNA and protein levels was observed in breast cancer, which was also related to the occurrence of primary tumors and lung metastasis;9 Kindlin-1 mRNA was highly expressed in various pancreatic cancer cells compared with normal pancreatic epithelial cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts, implying its potential as a promising biomarker for pancreatic carcinogenesis.11 Consistently, we here confirmed the overexpression of Kindlin-1 protein in osteosarcoma tissues using a large study group and also demonstrated its strong correlation with advanced clinicopathologic characteristics and poor prognosis in patients with osteosarcoma. Kindlin-2 (also named as mitogen inducible gene-2, Mig-2), functions as a scaffold protein to enhance Talin mediated integrin activation.26 Growing evidence shows the involvement of Kindlin-2 in cancer progression. For example, Guo et al27 indicated that Kindlin-2 may participate in epidermal growth factor receptor signaling and its depletion may impair epidermal growth factor-induced cell migration; Gong et al28 revealed that Kindlin-2 may control prostate cancer cell sensitivity to cisplatin; Ren et al29 showed the downregulation of Kindlin-2 in colorectal carcinoma tissues, and its overexpression may inhibit cell proliferation and migration, whereas its knockdown may promote the tumorigenicity of cancer cells in vitro, and in vivo, and Yu et al14 reported that Kindlin-2 may promote breast cancer invasion via epigenetic silencing of the microRNA-200 gene family. Here, our data demonstrated that the overexpression of Kindlin-2 protein was significantly associated with high tumor grade, the presence of metastasis and recurrence, poor response to chemotherapy and patients’ unfavorable prognosis. These findings suggest that Kindlin-2 plays different roles in human cancers, with a cancer-specific manner. Kindlin-3, also known as Mig-2B and FERMT3, functions as a regulator in the control of hemostasis and thrombosis.30 A large number of previous studies have observed that Kindlin-3 expression was significantly decreased in several cancer types such as melanoma, breast, and lung, when compared with the normal tissue counterparts.15–18 Similarly, our data also confirmed the downregulation of Kindlin-3 in human osteosarcoma tissues. Functionally, Kindlin-3 knockdown in breast cancer and melanoma models in vivo may markedly increase metastasis formation, in accord with the in vitro increase of tumor cell malignant properties, implying its tumor suppressive roles in these malignancies.16 However, our statistical analyses based on clinical data did not found any significant associations between the abnormal expression of Kindlin-3 protein and various clinicopathologic characteristics and clinical outcome of osteosarcoma patients, hence these results need further validation based on other independent clinical cohorts.

In conclusion, the expression levels of the three members of the Kindlin protein family are all abnormal in osteosarcoma tissues. Among them, the aberrant expression of Kindlin-1 and Kindlin-2 proteins may be closely correlated with the aggressive progression and poor prognosis of patients with osteosarcoma, implying the two Kindlin proteins might be promising therapeutic targets for improving the clinical outcome of this malignancy. However, the follow-up time of this clinical cohort was relatively short, which may lead to some unexpected results, for example, tumor grade was not identified as a prognostic factor in our survival. Thus, further studies based on independent clinical cohorts with long-term follow-up are required.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Authors’ contributions

KL participated in study design and coordination, material support for obtained funding, and supervised study. KN and HZ performed the experiments and data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. ZW carried out a part of data analysis. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

References

- 1.Yang J, Zhang W. New molecular insights into osteosarcoma targeted therapy. Curr Opin Oncol. 2013;25(4):398–406. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3283622c1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gill J, Ahluwalia MK, Geller D, Gorlick R. New targets and approaches in osteosarcoma. Pharmacol Ther. 2013;137(1):89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang YM, Hou CH, Hou SM, Yang RS. The metastasectomy and timing of pulmonary metastases on the outcome of osteosarcoma patients. Clin Med Oncol. 2009;3:99–105. doi: 10.4137/cmo.s531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poletajew S, Fus L, Wasiutyński A. Current concepts on pathogenesis and biology of metastatic osteosarcoma tumors. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2011;13(6):537–545. doi: 10.5604/15093492.971038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tian Z, Guo B, Yu M, et al. Upregulation of micro-ribonucleic acid-128 cooperating with downregulation of PTEN confers metastatic potential and unfavorable prognosis in patients with primary osteosarcoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2014;7:1601–1608. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S67217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang H, Yin Z, Ning K, Wang L, Guo R, Ji Z. Prognostic value of microRNA-223/epithelial cell transforming sequence 2 signaling in patients with osteosarcoma. Hum Pathol. 2014;45(7):1430–1436. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2014.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mu Y, Zhang H, Che L, Li K. Clinical significance of microRNA-183/Ezrin axis in judging the prognosis of patients with osteosarcoma. Med Oncol. 2014;31(2):821. doi: 10.1007/s12032-013-0821-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rognoni E, Ruppert R, Fässler R. The kindlin family: functions, signaling properties and implications for human disease. J Cell Sci. 2016;129(1):17–27. doi: 10.1242/jcs.161190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canning CA, Chan JS, Common JE, Lane EB, Jones CM. Developmental expression of the fermitin/kindlin gene family in Xenopus laevis embryos. Dev Dyn. 2011;240(8):1958–1963. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sin S, Bonin F, Petit V, et al. Role of the focal adhesion protein kindlin-1 in breast cancer growth and lung metastasis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(17):1323–1337. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhan J, Zhu X, Guo Y, et al. Opposite role of Kindlin-1 and Kindlin-2 in lung cancers. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e50313. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahawithitwong P, Ohuchida K, Ikenaga N, et al. Kindlin-1 expression is involved in migration and invasion of pancreatic cancer. Int J Oncol. 2013;42(4):1360–1366. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weinstein EJ, Bourner M, Head R, Zakeri H, Bauer C, Mazzarella R. URP1: a member of a novel family of PH and FERM domain-containing membrane-associated proteins is significantly over-expressed in lung and colon carcinomas. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1637(3):207–216. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(03)00035-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu Y, Wu J, Guan L, et al. Kindlin 2 promotes breast cancer invasion via epigenetic silencing of the microRNA200 gene family. Int J Cancer. 2013;133(6):1368–1379. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delyon J, Khayati F, Djaafri I, et al. EMMPRIN regulates β1 integrin-mediated adhesion through Kindlin-3 in human melanoma cells. Exp Dermatol. 2015;24(6):443–448. doi: 10.1111/exd.12693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sossey-Alaoui K, Pluskota E, Davuluri G, et al. Kindlin-3 enhances breast cancer progression and metastasis by activating Twist-mediated angiogenesis. FASEB J. 2014;28(5):2260–2271. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-244004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qu J, Ero R, Feng C, et al. Kindlin-3 interacts with the ribosome and regulates c-Myc expression required for proliferation of chronic myeloid leukemia cells. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18491. doi: 10.1038/srep18491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Djaafri I, Khayati F, Menashi S, et al. A novel tumor suppressor function of Kindlin-3 in solid cancer. Oncotarget. 2014;5(19):8970–8985. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bacci G, Bertoni F, Longhi A. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for high-grade central osteosarcoma of the extremity. Histologic response to preoperative chemotherapy correlates with histologic subtype of the tumor. Cancer. 2003;97(12):3068–3075. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao J, Xu H, He M, Wu Y. Glucocorticoid receptor DNA binding factor 1 expression and osteosarcoma prognosis. Tumour Biol. 2014;35(12):12449–12458. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2563-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liao Y, Feng Y, Shen J, et al. Clinical and biological significance of PIM1 kinase in osteosarcoma. J Orthop Res. 2016;34(7):1185–1194. doi: 10.1002/jor.23134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abd El-Rehim DM, Osman NA. Expression of a disintegrin and metalloprotease 8 and endostatin in human osteosarcoma: implication in tumor progression and prognosis. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2015;27(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jnci.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meves A, Stremmel C, Gottschalk K, Fässler R. The Kindlin protein family: new members to the club of focal adhesion proteins. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19(10):504–513. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plow EF, Qin J, Byzova T. Kindling the flame of integrin activation and function with kindlins. Curr Opin Hematol. 2009;16(5):323–328. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e32832ea389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larjava H, Plow EF, Wu C. Kindlins: essential regulators of integrin signalling and cell-matrix adhesion. EMBO Rep. 2008;9(12):1203–1208. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhan J, Yang M, Chi X, et al. Kindlin-2 expression in adult tissues correlates with their embryonic origins. Sci China Life Sci. 2014;57(7):690–697. doi: 10.1007/s11427-014-4676-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo B, Gao J, Zhan J, Zhang H. Kindlin-2 interacts with and stabilizes EGFR and is required for EGF-induced breast cancer cell migration. Cancer Lett. 2015;361(2):271–281. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gong X, An Z, Wang Y, et al. Kindlin-2 controls sensitivity of prostate cancer cells to cisplatin-induced cell death. Cancer Lett. 2010;299(1):54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ren Y, Jin H, Xue Z, et al. Kindlin-2 inhibited the growth and migration of colorectal cancer cells. Tumour Biol. 2015;36(6):4107–4114. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lai-Cheong JE, Parsons M, McGrath JA. The role of kindlins in cell biology and relevance to human disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42(5):595–603. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]