Abstract

Intraosseous hemangiomas are uncommon intrabony lesions, representing approximately 0.5 to 1% of all intraosseous tumors. Their description varies from “benign vasoformative neoplasms” to true hamartomatous proliferations of endothelial cells forming a vascular network with intermixed fibrous connective tissue stroma. These commonly present as a firm, painless swelling. Intraosseous hemangiomas present more commonly in females than in males and most likely occur in the fourth decade of life. The most common etiology of intraosseous hemangioma is believed to be prior trauma to the area. They have a tendency to bleed briskly upon removal or biopsy, making preoperative detection of the vascular nature of the lesion of significant importance. There are four variants: (1) capillary type, (2) cavernous type, (3) mixed variant, and (4) scirrhous type. Generally most common in the vertebral skeleton, they can also present in the calvarium and facial bones. In the head, the most common site is the parietal bone, followed by the mandible, and then malar and zygomatic regions. Intraosseous hemangiomas of the zygoma are rare entities with the first case reported in 1950 by Schoenfield. In this article, we review 49 case reports of intraosseous hemangioma of the zygoma, and also present a new case treated with excision followed by polyether-ether ketone implant placement for primary reconstruction.

Keywords: intraosseous hemangioma, PEEK implant, zygoma

Intraosseous hemangiomas are uncommon intrabony lesions, representing approximately 0.5 to 1% of all intraosseous tumors. Their description varies from “benign vasoformative neoplasms” to true hamartomatous proliferations of endothelial cells forming a vascular network with intermixed fibrous connective tissue stroma. These commonly present as a firm, painless swelling. Intraosseous hemangiomas present more commonly in females than in males and most likely occur in the fourth decade of life. The most common etiology of intraosseous hemangioma is believed to be prior trauma to the area. They have a tendency to bleed briskly upon removal or biopsy, making preoperative detection of the vascular nature of the lesion of significant importance. There are four variants:

Capillary type

Cavernous type

Mixed variant

Scirrhous type

Generally most common in the vertebral skeleton, they can also present in the calvarium and facial bones. In the head, the most common site is the parietal bone, followed by the mandible, and then malar and zygomatic regions. Intraosseous hemangiomas of the zygoma are rare entities with the first case reported in 1950 by Schoenfield.

In this article, we review 49 case reports of intraosseous hemangioma of the zygoma, and also present a new case treated with excision followed by polyether-ether ketone (PEEK) implant placement for primary reconstruction.

Case Report

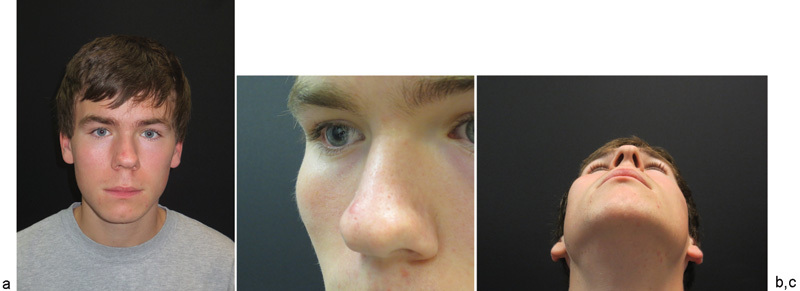

A 15-year-old male was referred to Duke University Medical Center for evaluation of an expanding lesion of the right zygoma in February 2013. The patient had no history of prior trauma to the region and was otherwise in an excellent state of health. He had noticed swelling in the malar area approximately 3 months before his presentation to Duke University, but was otherwise asymptomatic. Physical examination demonstrated a 3 × 3 cm area of firm bony outgrowth in the region of the right zygoma (Fig. 1). No palpable thrill or overlying inflammation was identified.

Fig. 1.

(a) Initial presentation of patient. (b) Lateral view of right zygoma showing expansion/prominence. (c) Inferior view of right zygoma displaying obvious expansion.

The patient reported a previous aspiration attempt, as it was originally believed to be an infected soft-tissue cyst by an outside plastic surgeon. When the lesion failed to resolve, the patient subsequently underwent a computed tomographic (CT) scan that demonstrated a destructive, enhancing, expanding mass of the right zygoma measuring approximately 3.8 × 2.6 × 2.6 cm (Fig. 2). The patient was then referred to an outside otolaryngologist who performed an incisional biopsy. The biopsy specimen was first evaluated at the Sentara Norfolk General Hospital in Norfolk, VA, and also by the University of Miami, Miami, FL, and the Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA. A consensus diagnosis of epithelioid hemangioma of bone was confirmed (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

(a) Initial presentation: computed tomographic (CT) coronal view indicating right zygoma expansion. (b) Initial presentation: CT axial view. (c) Initial presentation: 3D reconstruction indicating site of apparent intraosseous hemangioma.

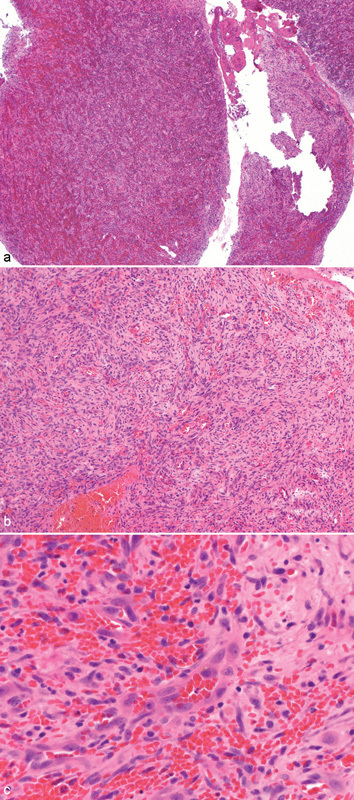

Fig. 3.

(a) Low-power histopathologic view displaying lesion with spindled cells and abundant pale cytoplasm. (b) Medium-power histopathologic view with better representation of spindled cells, abundant pale cytoplasm, and numerous erythrocytes. (c) High-power histopathologic view outlining vascular channels with generally smooth endothelial lining, scattered erythrocytes, and spindled cells.

Bilateral external carotid arteriograms were obtained preoperatively with a plan for possible embolization of potential high-flow contributory vessels. However, no vessels were embolized, as the bilateral common arteriograms were normal and there was no evidence of tumor neovascularization or arteriovenous malformation. The case was presented at the Duke University Vascular Anomalies Tumor Board where a unanimous decision was made to proceed with surgical resection only.

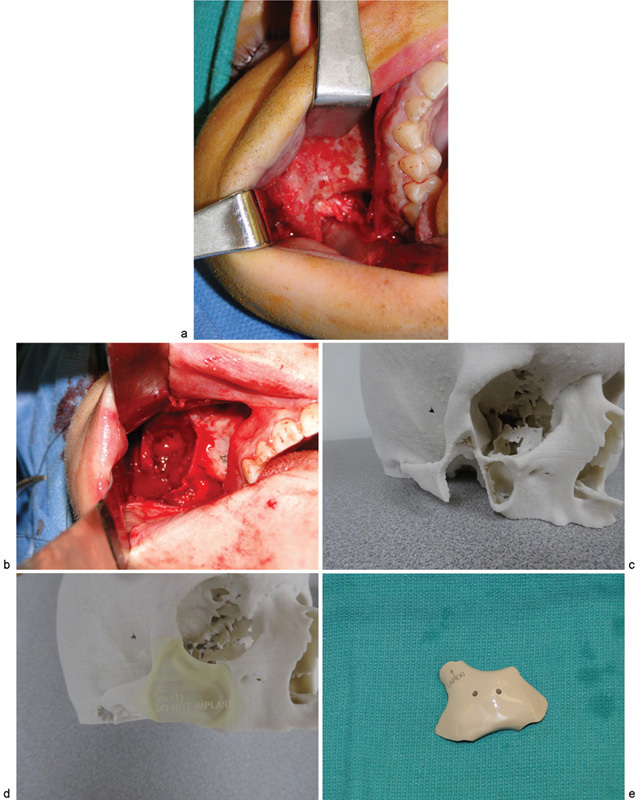

The patient was taken to the operating room and the lesion was resected using a combination of transconjunctival and intraoral approaches. A lateral canthotomy was completed to improve access to the operative site. The defect was reconstructed with a custom-fabricated PEEK implant (Fig. 4). A Frost tarsorrhaphy suture was utilized to suspend the lower eyelid and the specimen was submitted for histopathologic evaluation. The intraoperative bleeding was minimal and the blood loss was estimated to be 50 mL. The postoperative course was uneventful, the aesthetic outcome was excellent, and to date, there is no evidence of lesion recurrence (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

(a) Intraoperative view of intraosseous hemangioma. (b) Postresection of lesion. (c) Preoperative stereolithographic model indicating planned borders of resection. (d) Template for custom PEEK implant. (e) Custom PEEK implant mirrored from contralateral side reproducing the bony contours of the zygoma.

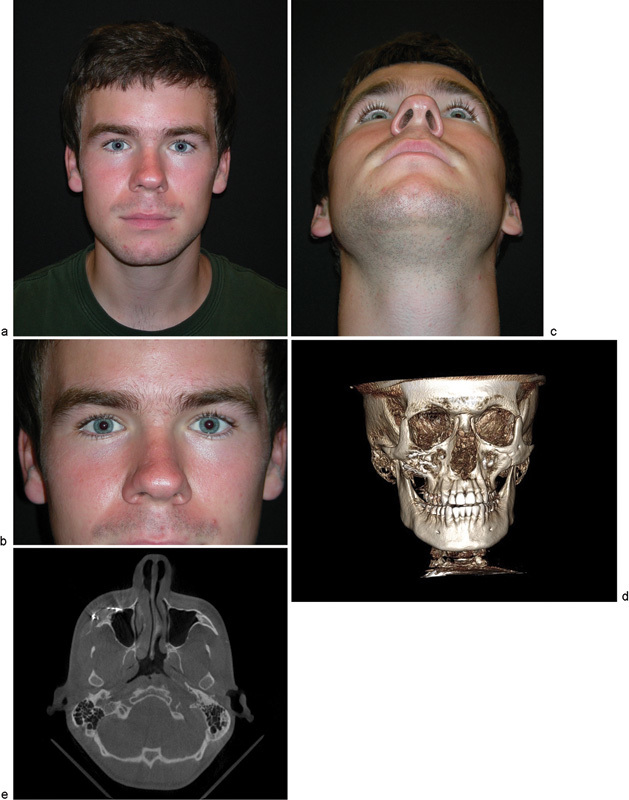

Fig. 5.

(a) 18-month postoperative view of the patient. (b) 18-month postoperative close-up of the bilateral orbitozygomatic region. (c) 18-month postoperative inferior view indicating acceptable uniformity of zygoma projection. (d) 18-month postoperative computed tomographic (CT) scan with 3D reconstruction. (e) 18-month postoperative CT axial scan indicating no evidence of recurrence of lesion.

Methods

A search was completed on PubMed for case reports of intraosseous hemangiomas of the zygoma. Reports of 49 case studies or series in either in English or translated into English were available in full text for our review. Of the 49 published reports, there were 39 documented case studies of intrazygomatic hemangiomas. The following information was extracted as raw data for each case: age, sex, location, size (measured either radiographically or by final excisional size), pain, swelling, radiographic findings, history of trauma, treatment rendered, whether reconstruction was required and if so with what material, time of follow-up, recurrences, intraoperative bleeding, and any ocular findings.

Results

Of the 49 cases (Table 1), 36 were females and 13 were males, representing approximately 3:1 prevalence in females as has been previously reported in the literature. The ages ranged from 1-day old to 72-year old, with the most common presentation in the fifth decade of life. This is contrary to previous reports that the most common presentation is in the second or fourth decade of life. Measurements were conducted either radiographically or upon excision. Six were measured less than 1 cm in greatest dimension. Twenty-four were greater than 1 cm but less than or equal to 2.5 cm in greatest dimension. Ten were greater than 2.5 cm in greatest dimension. In nine cases, the size of the tumor was unreported. Only 1 of the 49 patients presented with no swelling and the lesions were discovered incidentally on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Of the 49 patients, 24 reported pain as a symptom, while 18 reported no pain, 7 case reports did not mention whether the patient presented with pain. Seven patients had ocular findings at the time of presentation including dystopia, exorbitism, ptosis, and limitations of extraocular muscle movement.

Table 1. Literature review of craniofacial intraosseous hemangioma.

| Author | Age/Sex | Side, size | Duration | Pain | Ocular findings | H/o Trauma | Imaging | Management | Surgical approach | Reconstruction | Bleeding | Follow-up, Recurrence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Schofield (1950)22 | 1/M | R, 1 cm | 3 mo | N | ? | N | X-ray: bone mass with displacement of orbital floor | Excision | Infraorbital | Not required | ? | ? |

| 2 | Sherman and Wilner (1961)23 | 46/F | L, 2.5 cm | 2 y | N | ? | ? | X-ray: lytic lesion, sunray | Excision | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| 3 | Walker and McHenry (1965)17 | 40/F | L, 1.5 cm | 4 y | Y | ? | N | X-ray: radiotranslucent with trabeculated appearance | Excision | Lower lateral orbital rim | Not required | ? | No recurrence |

| 4 | Walker and McHenry (1965)17 | 10/F | L, 1.5 cm | 5 mo | Y | N | Y, 6–8 wk prior to presentation | X-ray: irregularity with bony spicules radiating outward | Excision | Lower lateral orbital rim | Not required | ? | No recurrence |

| 5 | Davis and Morgan (1974)24 | 47/F | L, 2 cm | 2 y | Y | ? | ? | X-ray: reticulated internal pattern; carotid arteriogram with tumor “blush” | Ligation of left ECA, excision | Infraorbital | Autogenous rib graft 6 mo after excision | ? | ? |

| 6 | Brackup et al (1980)25 | 46/F | R, 1 cm | 2 mo | Y | N | N | X-ray: honeycomb, sunray; T99 scan: increased nucleotide concentration | Excision | Orbital floor fracture approach | Not required | Y, during excision | ? |

| 7 | Marshak (1980)2 | 53/F | R, 2 × 2.5 cm | 1.5 y | Y | ? | h/o Caldwell-Luc for chronic suppurative sinusitis 21 y prior | X-ray: reticulated honeycomb | Excision | Lower blepharoplasty | Filled with pedicled infratemporal fatty tissue | ? | 2 y, no recurrence |

| 8 | Marshak (1980)2 | 35/F | L, 2 cm | 1 y | Y | Y, Superior displacement of globe | N | X-ray: reticulated, internal pattern | Excision | Lower blepharoplasty | Filled with pedicled infratemporal fatty tissue | Y, during excision | 20 mo, no recurrence |

| 9 | Schmidt (1982)26 | 43/F | R, 5 × 7 mm | ? | N | ? | Y | X-ray: sunburst | Excision | Lower blepharoplasty | Layer of Surgicel | N | No recurrence |

| 10 | Har-El et al (1986)27 | 60/M | R, 4 cm | 2 y | Y | ? | N | X-ray: tumor in the maxillary sinus; CT: mass originates in zygomatic bone | Caldwell-Luc | Infraorbital | Not required | ? | ? |

| 11 | Har-El et al (1987)28 | 43/F | L, 1.5 × 1.5 cm | 2 y | N | ? | N | X-ray: irregular reticular internal pattern | Excision | Infraorbital | Silicone layer in pentagon shape | N | 10 y, no recurrence |

| 12 | Har-El et al (1987)28 | 58/M | R, 2 × 2 cm | 3 mo | N | Y, upward displacement of orbital floor | N | X-ray: space-occupying lesion with upward displacement of orbital floor | Excision | Infraorbital | Silicone layer cut into shape of excised specimen | N | ? |

| 13 | Warman and Myssiorek (1989)29 | 38/F | L, 3.5 × 2 cm | 4 mo | Y | ? | N | X-ray: inconclusive; CT: well-circumscribed, fibrous dysplasia; MRI: isointense T1, hyperintense on T2 | En bloc excision | ? | Iliac crest bone graft | Y, during biopsy | 1 y, no recurrence |

| 14 | Jeter et al (1990)30 | 1 day old/M | L, 1 cm | ? | Y | N | N/A | X-ray: poorly defined loss of cortex | Ligated and divided left ECA; excision | Weber-Fergusson via cleft lip | Not required | N | 6 y, no recurrence |

| 15 | Jeter et al (1990)30 | 50/F | L, 1.5 cm | 1 y | N | ? | N | X-ray: radiolucent lesion; ECA and ICA angiograms | Complete resection | Subciliary | Iliac crest bone graft | ? | 4 y, no recurrence |

| 16 | Nishimura et al (1990)31 | 69/M | L, ? | 5 y | ? | Y, ptosis | ? | CT: expansive soft-tissue density; MRI: T1 low signal intensity and T2 high signal intensity; selective common carotid angiography | Preoperative embolization; Complete resection | Hemi-coronal with preauricular extension | Vascularized outer-table calvarial bone flap | N | 4 wk, no recurrence |

| 17 | Clauser et al (1991)32 | 56/F | R, 3 cm | 4 y | N | ? | ? | CT; right ECA arteriogram | Complete resection | Bicoronal and subciliary | Split calvarial bone graft | N | ? |

| 18 | Clauser et al (1991)32 | 35/F | L, 2.5 cm | 1 y | Y | ? | ? | CT; left ECA arteriogram | Complete resection | Bicoronal and subciliary | Split thickness calvarial graft | ? | ? |

| 19 | Cuesta Gil and Navarro-Vila (1992)33 | 12/F | L, 4 × 5 cm | 4 y | Y | Y, superior displacement of globe | N | X-ray: radiopaque, sunburst; left carotid arteriogram: tumor “blush” | Preoperative embolization; Complete resection | Coronal and infraorbital | Inner table of parietal bone | ? | 3 y, no recurrence |

| 20 | De Ponte et al (1995)34 | 60/M | R, ? | ? | N | ? | ? | CT | Preoperative embolization; Radical excision | Hemicoronal and subciliary | 2 calvarial grafts | N | ? |

| 21 | De Ponte et al (1995)34 | 43/F | R, ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | CT | Preoperative embolization; Radical excision | ? | Calvarial graft | N | ? |

| 22 | Hirano et al (1997)35 | 42/F | R, 1.5 cm | 16 mo | N | ? | N | CT: radiolucent intraosseous tumor | Excision | ? | Hydroxyapatite implant block | ? | 4 y, no recurrence |

| 23 | Hirano et al (1997)35 | 46/M | R, 1.5 cm | 1 y | N | ? | N | CT: low-density tumor without invasion | Excision | ? | Hydroxyapatite implant block | ? | 8 mo, no recurrence |

| 24 | Pinna 199715 | 56/F | R, ? | 4 y | N | N | ? | CT: honeycomb; right ECA angiography negative | Complete resection | ? | Full-thickness calvarial graft | ? | ? |

| 25 | Pinna et al (1997)15 | 35/F | L, ? | 1 y | Y | ? | ? | X-ray: radiolucent lesion; CT: sunburst; Left ECA angiography negative | Complete resection | Coronal and subciliary | Partial-thickness calvarial graft | ? | ? |

| 26 | Savastano et al (1997)36 | 41/F | R, 3 × 1 cm | 12 y | Y | ? | N | CT: mixed density mass | Complete resection | Hemicoronal and subciliary | Calvarial flap pedicled on temporalis fascia | Y, during resection | 8 mo, no recurrence |

| 27 | Kiratli and Orhan (1998)37 | 36/M | R, 1.5 × 1 cm | 10 y | N | N | N | CT: lytic lesion in maxilla; MRI: 3 y after CT, 3 lesions, one in right zygoma | Refused | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 28 | Konior et al (1999)12 | 45/F | R, 2 cm | 6 mo | ? | N | ? | X-ray: radiolucent; bone scan: increased radionucleotide uptake; CT: suggestive of fibrous dysplasia | Complete resection | Sublabial-subciliary approach | Split calvarial bone graft | Y, during biopsy | 6 mo, no recurrence |

| 29 | Moore et al (2001)3 | 31/F | L, 2.5 cm | 3 mo | N | Y, progressive dystopia | N | CT: spoke-wheel appearance; MRI: high T2 signal intensity; arteriogram: cluster of grapes | Preoperative embolization; Incisional biopsy; En bloc resection | Subciliary | Medpor for zygoma, titanium mesh for orbital floor; Alloderm patch for maxillary sinus | Y, during biopsy | ? |

| 30 | Sary et al (2001)38 | 46/M | R, 1.5 × 1.5 cm | 5 y | ? | ? | ? | CT: varying bony and soft-tissue densities | Complete resection | Subciliary | Porous polyethylene block was carved to fit into defect | ? | 2 y, no recurrence |

| 31 | Koybasi et al (2003)8 | 33/F | R, 2 × 1 cm | 2 mo | N | ? | ? | CT: hypointense intraosseous mass, honeycomb | Complete resection | ? | Hydroxyapatite material | N | 1.5 y, no recurrence |

| 32 | Leibovitch et al (2003)39 | 47/F | R, ? | 2 y | N | ? | ? | CT: honeycomb | En bloc resection | Temporal skin incision | ? | Y, during resection | 2 y, no recurrence |

| 33 | Taylan et al (2003)14 | 30/M | L, 2 × 1 cm | 3 mo | N | ? | N | CT: spongy bony appearance with lobulation | Partial resection | Subciliary and gingivobuccal | Not required | ? | No recurrence |

| 34 | Ramchandani et al (2004)20 | 38/F | L, 4 cm | ? | N | Y, orbital floor fracture | Y, 2 y prior | X-ray: radiopaque; CT: trabeculated mass, orbital floor fracture | Incisional biopsy | Hemicoronal | Pedicled calvarial flap | Y, during biopsy | ? |

| 35 | Yan et al (2005)40 | 46/F | L, 2 × 2 × 1.5 cm | 2 y | ? | N | ? | CT: high-density mass with clear boundary | Excision | Anterior orbitotomy | Not required | ? | 2 y, no recurrence |

| 36 | Yan et al (2005)40 | 50/F | R, 2 × 2 × 1.5 cm | 6 mo | ? | N | ? | CT: bony thickening | Excision | Lower lateral orbital rim | Not required | ? | 6 mo, no recurrence |

| 37 | Cheng et al (2006)7 | 50/F | R, 1.4 × 1.2 cm | ? | N | N | ? | ? | Partial resection with local recurrence; complete resection after 3 y | ? | ? | ? | 6 mo, recurrence |

| 38 | Riveros et al (2006)41 | 72/F | L, ? | ? | N | Y, intraocular mass during routine eye exam, proptosis, superior and inferior restriction of eye motility | N | MRI; CT | Orbitotomy with incisional biopsy; surveillance | ? | N/A | ? | N/A |

| 39 | Zins et al (2006)42 | 36/F | L, 2.5 × 2.5 cm | ? | ? | ? | ? | CT: salt and pepper appearance | Complete resection | Coronal, subciliary, intraoral | Full-thickness left parietal bone | ? | 6 y, no recurrence |

| 40 | Gómez et al (2008)13 | 35/F | R, 4 cm | 3 y | N | N | ? | CT: well-defined, hypodense, reticular pattern, honeycomb, soap bubble | En bloc resection | Sublabial-subciliary approach and bicoronal flap | Outer table calvarial bone graft; pediculated temporoparietal galea-pericranium flap; Bichat fatty ball flap to isolate maxillary sinus | Y, during biopsy | 1 y, no recurrence |

| 41 | Valentini et al (2008)43 | 57/M | L, ? | ? | Y | ? | N | CT: lytic lesion | Incisional biopsy; complete resection | Semicoronal, lower eyelid | Right 5th rib | ? | ? |

| 42 | Arribas-Garcia et al (2009)19 | 42/F | L, 3 cm | “several years” | N | ? | ? | CT: expansile and lytic lesion; repeat CT; MRI | Surveillance for 5 years; Complete resection | Intraoral and coronal | Alloplastic prosthesis | ? | 1 y, no recurrence |

| 43 | Madge et al (2009)44 | 49/F | R, ? | 1.5 y | Y | N | ? | MRI: enhanced contrast; CT | Excision | Transconjunctival swinging eyelid | Not required | N | ? |

| 44 | Srinivasan et al (2009)9 | 66/F | R, 3 × 3 cm | 4 y | N | N | N | CT: radiating spoke wheel | Excision | ? | Not required | N | 2.5 y, no recurrence |

| 45 | Defazio et al (2012)10 | 58/F | R, 1 × 1.5 cm | 2 y | N | N | Y | CT: sunburst; MRI: T2 with high signal intensity | Incisional biopsy; Surveillance | ? | Not required | ? | ? |

| 46 | Defazio et al (2012)10 | 53/F | R, 1 × 1.8 cm | ? | Y | ? | N | CT and MRI consistent with dx of intraosseous venous malformation | Initial incisional biopsy non-diagnostic; Surveillance; Complete resection 2 y later | ? | Split calvarial bone graft | ? | ? |

| 47 | Defazio et al (2012)10 | 49/M | R, 1 cm | 6 mo | N | N | N | CT: honeycomb | Complete resection | ? | Bone harvested from zygomatic buttress | ? | ? |

| 48 | Dhupar et al (2012)45 | 34/F | L, 4 × 3 × 2 cm | 7 y | Y | ? | Y, 7 y prior to presentation | X-ray: honeycomb; CT: mixed density lesion | Incisional biopsy; complete resection | Lateral canthotomy | Not required | Y, during biopsy | ? |

| 49 | Marcinow et al (2012)46 | 47/M | L, 2 × 2.5 cm | 6 mo | Y | N | N | CT: ground-glass | Complete resection | Sublabial and transconjunctival | ? | ? | ? |

| 50 | Present case | 15/M | R, 3.8 × 2.6 × 2.6 cm | 3 mo | N | N | N | CT; MRI; arteriograms | Incisional biopsy; en bloc resection | Transconjunctival and intraoral | Custom-fabricated polyether-ether ketone implant | N | 1 y, no recurrence |

Abbreviations: ?, unknown; CT, computed tomography; ECA, -----; F, female; M, male; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; mo, month; N, no; wk, week; Y, yes; y, year.

Trauma is believed to be the most common etiology of intraosseous hemangiomas, but only 6 of the 49 cases were reported a previous trauma to the area. Twenty-two cases reported no previous trauma, and 11 cases did not report, or the patients were unsure of previous trauma, to the site. Only two cases were managed with incisional biopsy followed by surveillance. One patient refused treatment. The remaining patients were treated with excision or complete resection. Of those 46 who underwent excision or resection, only 13 did not require reconstruction. Twenty-nine of the 46 patients who underwent surgical removal required some type of reconstruction, while the need for reconstruction was not reported on 4 of the cases. Reconstruction was not required on any of the cases with tumors measuring 1 cm or less. It was also not required on 3 of the 10 cases with tumors measuring >2.5 cm in greatest dimension. For reconstruction, 18 cases were reconstructed with bone, 3 were reconstructed with hydroxyapatite, 5 used silicone or other synthetic or titanium materials, and 2 required soft-tissue fat grafting only. Histopathologic examination revealed 5 capillary hemangiomas, 25 cavernous hemangiomas, and 3 mixed hemangiomas. Five patients underwent preoperative embolization or ligation of branches of the external carotid artery prior to treatment. Reported follow-up period ranged from 4 weeks to 10 years. Two reported cases of recurrence were both discovered at 6-month follow-up. Twenty-one cases did not report follow-up data or recurrence.

Discussion

Primary intraosseous hemangiomas of the zygoma are rare pathologic lesions with only 49 published cases in the literature to date, not including the case described earlier. Patients generally present with malar asymmetry and bony mass and are often otherwise asymptomatic. If symptomatic, the most common complaint is pain (49%) followed by ocular findings (14.2%) related to the mass effect. Ocular findings include dystopia, exorbitism, ptosis, and impingement of extraocular muscle movement.

Despite the fact that trauma is believed by many to be a common cause of primary intraosseous hemangiomas, only six cases had a prior history of trauma (12.2%), one of which was prior surgical trauma.1 2 3 Traumatic injury is believed to predispose to periods of accelerated growth.4 In contrast, others have suggested that these lesions are congenital.2 5 6 7 Given the relatively few cases that report a history of trauma and the occurrence of two cases during infancy, we support the theory that these lesions are congenital. If they are congenital, the late onset of these lesions in the fifth decade of life is certainly curious.

CT scan remains the diagnostic imaging modality of choice for the diagnosis of intraosseous hemangiomas and was the most common imaging modality utilized by clinicians for evaluating these lesions.7 8 CT scan is often preferred because of improved characterization of cortical and trabecular detail to a greater extent than alternative imaging modalities.3 In contrast to their soft-tissue counterparts, the CT characteristics of primary intraosseous venous malformations have not been well elucidated.9 The radiographic appearance is often described as “honeycomb,” “soap bubble,” or “sunburst,”3 Though these lesions may initially raise concern for osteosarcoma, upon close inspection the cortical border will be intact, highlighting the benign nature of these lesions.10

Several authors have advocated the use of MRI instead of CT.1 7 11 MRI provides not only superior soft-tissue evaluation, but the high-signal enhancement in water-sensitive, T2-weighted sequences allow for assessment of fluid-filled lesions.3 Arteriograms can be utilized if there is concern for high-flow malformations and can be therapeutically advantageous if endovascular intervention is desired, though the benefits of selective embolization are believed to be limited.2 8 12 13 Several clinicians in the cases reviewed ordered preoperative MRIs and arteriograms, but rarely selective embolization was utilized. Overall, the utility of MRI and arteriograms in the treatment of zygomatic intraosseous hemangiomas remains to be elucidated.

Management of primary intraosseous hemangiomas of the zygoma depends on both symptoms and cosmetic considerations and varies according to the location and extent of the lesion. Indications for surgical intervention include cosmesis, hemorrhage, and complications of mass effect.7 10 14 15 Because these lesions are benign, observation is an option for asymptomatic individuals.7 However, of the cases identified, only two patients were managed with surveillance; both denied pain and ocular symptomatology. Another patient initially opted for surveillance but then returned for complete resection. Given the expanding nature of these lesions, it is likely that those that initially choose surveillance may later decide on resection due to aesthetic concerns.

In contrast to soft-tissue venous malformations in which various treatment options have been described, complete surgical resection remains the treatment of choice for primary intraosseous hemangiomas.7 10 16 17 Recurrence is higher in individuals undergoing partial resection7; the literature review did not identify any cases recurrence after en bloc resection. However, there may be theoretical increased risk of complications and the issue of reconstruction with more extensive en bloc resections compared with partial resections.7

The reconstruction method is more controversial, but lesions greater than 1 cm generally require reconstruction. Primary reconstruction with autogenous bone is most commonly utilized with calvarial grafts being most commonly applied (28.6%). Primary reconstruction prevents soft-tissue contraction, which can be difficult to correct should it occur.18 Several authors have utilized alloplastic implant prostheses, such as the PEEK implant we described in the aforementioned case. Preoperative imaging can be employed to create custom-fabricated PEEK implants with the advantages of avoiding donor site morbidity and decreasing surgical time.19 Because the zygoma represents a keystone of facial aesthetics, custom implants that mirror the unaffected side may result in an improved aesthetic outcome though satisfactory cosmesis has been reported with both autogenous grafting and alloplastic techniques.20

Though hemorrhage is a potential serious complication, more cases reported brisk bleeding during incisional biopsies (12.2%) than during resection (8.2%). The bleeding that occurred during biopsy procedures was controlled with local measures and cautery. En bloc resection with adequate bony margins appears to minimize the risk of massive bleeding.8 13 21 Therefore, despite the vascular nature of these lesions, hemorrhage is a rare complication.

Conclusion

Primary intraosseous hemangiomas of the zygoma are rare lesions of likely congenital origin that often present as a bony outgrowth resulting in facial asymmetry. Various imaging modalities can be utilized to characterize these benign outgrowths; MRI and arteriograms may be useful in evaluating the vascular nature of these lesions, especially if there is concern for high-flow malformations. En bloc resection with primary reconstruction using autogenous bone grafts has been used to treat the majority of these lesions, though there may be a new role for alloplastic materials in reconstructing these deficits. Here, we report the first case of reconstruction with PEEK implant placement with an excellent esthetic result. En bloc resection also minimizes the risk of bleeding, a complication seen more frequently when these lesions are biopsied.

References

- 1.Sweet C, Silbergleit R, Mehta B. Primary intraosseous hemangioma of the orbit: CT and MR appearance. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18(2):379–381. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marshak G. Hemangioma of the zygomatic bone. Arch Otolaryngol. 1980;106(9):581–582. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1980.00790330061017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore S L, Chun J K, Mitre S A, Som P M. Intraosseous hemangioma of the zygoma: CT and MR findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22(7):1383–1385. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ethunandan M, Mellor T K. Haemangiomas and vascular malformations of the maxillofacial region—a review. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;44(4):263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2005.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zucker J J, Levine M R, Chu A. Primary intraosseous hemangioma of the orbit. Report of a case and review of literature. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;5(4):247–255. doi: 10.1097/00002341-198912000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Relf S J Bartley G B Unni K K Primary orbital intraosseous hemangioma Ophthalmology 1991984541–546., discussion 547 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng N C, Lai D M, Hsie M H, Liao S L, Chen Y B. Intraosseous hemangiomas of the facial bone. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(7):2366–2372. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000218818.16811.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koybasi S, Saydam L, Kutluay L. Intraosseous hemangioma of the zygoma. Am J Otolaryngol. 2003;24(3):194–197. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(02)32429-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Srinivasan B, Ethunandan M, Van der Horst C, Markus A F. Intraosseous ‘haemangioma’ of the zygoma: more appropriately termed a venous malformation. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;38(10):1066–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Defazio M V, Kassira W, Camison L. et al. Intraosseous venous malformations of the zygoma: clarification of misconceptions regarding diagnosis and management. Ann Plast Surg. 2014;72(3):323–327. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3182605690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seeff J, Blacksin M F, Lyons M, Benevenia J. A case report of intracortical hemangioma. A forgotten intracortical lesion. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;(302):235–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Konior R J, Kelley T F, Hemmer D. Intraosseus zygomatic hemangioma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;121(1):122–125. doi: 10.1016/s0194-5998(99)70138-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gómez E, González T, Arias J, Lasaletta L. Three-dimensional reconstruction after removal of zygomatic intraosseous hemangioma. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;12(3):159–162. doi: 10.1007/s10006-008-0115-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylan G, Yildirim S, Gideroğlu K, Aköz T. Conservative approach in a rare case of intrazygomatic hemangioma. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112(5):1490–1492. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000080511.23265.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pinna V, Clauser L, Marchi M, Castellan L. Haemangioma of the zygoma: case report. Neuroradiology. 1997;39(3):216–218. doi: 10.1007/s002340050397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu M S, Kim H C, Jang Y J. Removal of a nasal bone intraosseous venous malformation and primary reconstruction of the surgical defect using open rhinoplasty. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39(4):394–396. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2009.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walker E A Jr, McHenry L C. Primary hemangioma of the zygoma. Arch Otolaryngol. 1965;81:199–203. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1965.00750050206017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zins J E, Long K, Papay F A. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1999. The use of cranial bone for midface and skull reconstruction. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arribas-Garcia I, Alcala-Galiano A, Fernandez Garcia A, Montalvo J J. Zygomatic intraosseous haemangioma: reconstruction with an alloplastic prosthesis based on a 3-D model. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63(5):e451–e453. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2009.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramchandani P L, Sabesan T, Mellor T K. Intraosseous vascular anomaly (haemangioma) of the zygoma. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;42(6):583–586. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Ponte F S, Bottini D J, Valentini V. [Surgical treatment of hemangioma of bones of the orbito-zygomatic region] Minerva Stomatol. 1994;43(7–8):365–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schofield A L. Primary hemangioma of the malar bone. Br J Plast Surg. 1950;3(2):136–140. doi: 10.1016/s0007-1226(50)80021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sherman R S, Wilner D. The roentgen diagnosis of hemangioma of bone. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1961;86:1146–1159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis E, Morgan L R. Hemangioma of bone. Arch Otolaryngol. 1974;99(6):443–445. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1974.00780030457011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brackup A H, Haller M L, Danber M M. Hemangioma of the bony orbit. Am J Ophthalmol. 1980;90(2):258–261. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)74865-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmidt G H. Hemangioma in the zygoma. Ann Plast Surg. 1982;9(4):330–332. doi: 10.1097/00000637-198210000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Har-El G, Levy R, Avidor I, Segal K, Sidi J. Haemangioma of the zygoma presenting as a tumour in the maxillary sinus. J Maxillofac Surg. 1986;14(3):161–164. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0503(86)80284-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Har-El G, Hadar T, Zirkin H Y, Sidi J. Hemangioma of the zygoma. Ann Plast Surg. 1987;18(6):533–540. doi: 10.1097/00000637-198706000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warman S, Myssiorek D. Hemangioma of the zygomatic bone. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1989;98(8, Pt 1):655–658. doi: 10.1177/000348948909800817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jeter T S, Hackney F L, Aufdemorte T B. Cavernous hemangioma of the zygoma: report of cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48(5):508–512. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(90)90242-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nishimura T, Takimoto T, Umeda R, Kadoya M, Takashima T, Mizukami Y. Osseous hemangioma arising in the facial bone. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1990;52(6):385–390. doi: 10.1159/000276168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clauser L, Meneghini F, Riga M, Rigo L. Haemangioma of the Zygoma. Report of two cases with a review of the literature. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1991;19(8):353–358. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(05)80278-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cuesta Gil M, Navarro-Vila C. Intraosseous hemangioma of the zygomatic bone. A case report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992;21(5):287–291. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(05)80739-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Ponte F S, Becelli R, Rinna C, Sassano P P. Aesthetic and functional reconstruction in intraosseus hemangiomas of the zygoma. J Craniofac Surg. 1995;6(6):506–509. doi: 10.1097/00001665-199511000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hirano S, Shoji K, Kojima H, Omori K. Use of hydroxyapatite for reconstruction after surgical removal of intraosseous hemangioma in the zygomatic bone. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;100(1):86–90. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199707000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Savastano G, Russo A, Dell'Aquila A. Osseous hemangioma of the zygoma: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;55(11):1352–1356. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(97)90201-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kiratli H, Orhan M. Multiple orbital intraosseous hemangiomas. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;14(5):345–348. doi: 10.1097/00002341-199809000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sary A, Yavuzer R, Latfoğlu O, Celebi M C. Intraosseous zygomatic hemangioma. Ann Plast Surg. 2001;46(6):659–660. doi: 10.1097/00000637-200106000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leibovitch I, Dray J P, Leibovitch L, Brazowski E. Primary intraosseous hemangioma of the zygomatic bone. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111(1):519–521. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200301000-00125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yan J, Cai Y, Wu Z, Han J, Pang Y. Cavernous hemangioma of the bony orbit. Yan Ke Xue Bao. 2005;21(3):147–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Riveros L G, Simpson E R, DeAngelis D D, Howarth D, McGowan H, Kassel E. Primary intraosseous hemangioma of the orbit: an unusual presentation of an uncommon tumor. Can J Ophthalmol. 2006;41(5):630–632. doi: 10.1016/S0008-4182(06)80037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zins J E Türegün M C Hosn W Bauer T W Reconstruction of intraosseous hemangiomas of the midface using split calvarial bone grafts Plast Reconstr Surg 20061173948–953., discussion 954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Valentini V, Nicolai G, Lorè B, Aboh I V. Intraosseous hemangiomas. J Craniofac Surg. 2008;19(6):1459–1464. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e318188a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Madge S N, Simon S, Abidin Z. et al. Primary orbital intraosseous hemangioma. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;25(1):37–41. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e318192a27e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dhupar V, Yadav S, Dhupar A, Akkara F. Cavernous hemangioma—uncommon presentation in zygomatic bone. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23(2):607–609. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31824cd7c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marcinow A M Provenzano M J Gurgel R K Chang K E Primary intraosseous cavernous hemangioma of the zygoma: a case report and literature review Ear Nose Throat J 2012915210, 212, 214–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]