Abstract

Silver nanoparticles plays a vital role in the development of new antimicrobial substances against a number of pathogenic microorganisms. These nanoparticles due to their smaller size could be very effective as they can improve the antibacterial activity through lysis of bacterial cell wall. Green synthesis of metal nanoparticles using various plants and plant products has recently been successfully accomplished. However, few studies have investigated the use of industrial waste materials in nanoparticle synthesis. In the present investigation, synthesis of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) was attempted using the aqueous extract of corn leaf waste of Zea mays, which is a waste material from the corn industry. The synthesized AgNPs were evaluated for their antibacterial activity against foodborne pathogenic bacteria (Bacillus cereus ATCC 13061, Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 19115, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 49444, Escherichia coli ATCC 43890, and Salmonella Typhimurium ATCC 43174) along with the study of its synergistic antibacterial activity. The anticandidal activity of AgNPs were evaluated against Candida species (C. albicans KACC 30003 and KACC 30062, C. glabrata KBNO6P00368, C. geochares KACC 30061, and C. saitoana KACC 41238), together with the antioxidant potential. The biosynthesized AgNPs were characterized by UV-Vis spectrophotometry with surface plasmon resonance at 450 nm followed by the analysis using scanning electron microscope, X-ray diffraction, Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy and thermogravimetric analysis. The AgNPs displayed moderate antibacterial activity (9.26–11.57 mm inhibition zone) against all five foodborne pathogenic bacteria. When AgNPs were mixed with standard antibacterial or anticandidal agent, they displayed strong synergistic antibacterial (10.62–12.80 mm inhibition zones) and anticandidal activity (11.43–14.33 mm inhibition zones). In addition, the AgNPs exhibited strong antioxidant potential. The overall results highlighted the potential use of maize industrial waste materials in the synthesis of AgNPs and their utilization in various applications particularly as antibacterial substance in food packaging, food preservation to protect against various dreadful foodborne pathogenic bacteria together with its biomedical, pharmaceutical based activities.

Keywords: antibacterial, anticandidal, antioxidant, foodborne bacteria, green synthesis, silver nanoparticles, Zea mays

Introduction

Nanotechnology is an emerging field of interdisciplinary research that includes all spheres of science starting from physics, chemistry, biology, and especially biotechnology (Natarajan et al., 2010). Nanoparticles (NPs) are a group of materials synthesized from a number of metals or non-metal elements with distinct features and extensive applications in different fields of science and medicine (Matei et al., 2008). Among them, silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) have been extensively studied because of their good electrical conductivity, as well as their potential for use in optical applications in nonlinear optics, as spectrally selective coatings for solar energy absorption, biolabeling, intercalation materials for electrical batteries as optical receptors, and catalysts in chemical reactions. Nanoparticles also have potential biological applications, such as biosensing, catalysis, drug delivery, imaging, nano device fabrication, and for use as antimicrobial agents and in medicine (Ghosh et al., 1996; Geddes et al., 2003; Nair and Laurencin, 2007; Jain et al., 2008; Sharma et al., 2009; Zargar et al., 2014). AgNPs release Ag+ ions that interact with the thiol groups in bacterial proteins and affect the DNA replication, resulting in destruction of the bacteria (Marini et al., 2007). Additionally, nanoparticles have been shown to have potential anti-bacterial activity and significantly higher synergistic effects when applied with many antibiotics (Devi and Joshi, 2012).

Synthesis of AgNPs employing chemical and physical methods has been extensively studied throughout the world; however, these methods are often environmentally toxic, technically laborious and economically expensive (Gopinath et al., 2012). Accordingly, biological methods for synthesis of AgNPs using plants, microorganisms and enzymes have been suggested as possible eco-friendly alternatives (Mohanpuria et al., 2008). The synthesis of AgNPs using plants or plant extracts as reducing and capping agents is considered advantageous over other biological processes because they eliminate the need for the elaborate process of culturing and maintaining biological cells, and can be scaled up for large-scale nanoparticle synthesis (Saxena et al., 2012; Valli and Vaseeharan, 2012). Overall, plant-mediated nanoparticles synthesis is a cost-effective, environmentally friendly, a single-step method for biosynthesis process that is safe for various human therapeutic and food based uses (Kumar and Yadav, 2009). Generally, the AgNO3 is reduced by the action of the reducing agents (plant extracts) to form silver nanoparticles which are further stabilized by the bioactive compounds from the biological extracts to form a stable silver nanoparticle.

During recent years, the use of agricultural and industrial wastes in the synthesis of different types of metal nanoparticles has been extensively investigated (Basavegowda and Lee, 2013; Ramamurthy et al., 2013; Nezamdoost et al., 2014) A number of food crops are industrially used for production of different types of food products and processed food. Among these, maize (Zea mays) is widely used throughout the world for production of popcorn, chips, corn oil, corn starch, and many other materials. Only the kernels of the corn plant are edible, while rest of the crop are occasionally used as animal feed or ingredients in beverages. Different parts of the maize plant have been effectively utilized in traditional medicines as strong therapeutic agents (Konstantopoulou et al., 2004; Ullah et al., 2010; Solihah et al., 2012). A number of bioactive compounds, such are polyphenols (chlorogenic acid, caffeic acid, rutin, ferulic acid, morin, quercetin, naringenin, and kaempferol), anthocyanins, flavonoids, flavonols, and flavanols have been reported to be present in the Z. mays plant and its various parts such kernel, leaves, roots etc., which are responsible for its antioxidant, antiinflammatory and other medicinal potential (Ramos-Escudero et al., 2012; Bacchetti et al., 2013; Pandey et al., 2013). Hence utilization of maize waste materials in the synthesis of nanoparticles would be a profitable approach in ecofriendly and cost effective nanoparticle synthesis.

Recently there is emergence of multi drug resistant pathogenic bacterial strains and most of the available antibiotics are not active against these pathogens (Andersson and Hughes, 2010; Huh and Kwon, 2011). These drug resistant pathogens are more pathogenic with high mortality rate than that of wild strain. The scientific community is continuously searching for a new classes of disinfection systems that could act efficiently against these pathogens. Silver-containing systems, and especially the AgNPs are these days one of the strong alternatives in search for various antibacterial drugs, as these nanoparticles have been reported previously to exhibit interesting antibacterial activities against a broad spectrum of pathogenic bacteria (Shahverdi et al., 2007; Lara et al., 2011; Guzman et al., 2012; Rai et al., 2012; Ouay and Stellacci, 2015). However, studies on AgNPs are still under investigation as antimicrobial and the studies performed since now demonstrated that a case by case evaluation have to be done for each nanoparticle and bacterial target. The bactericidal effects of ionic silver and the antimicrobial activity of colloidal silver particles is generally influenced by the size of the particles, i.e., the smaller the particle size, the greater the antimicrobial activity (Zhang et al., 2003).

There are many advantages of AgNPs to be used as an effective antimicrobial agents. They are highly effective against a broad range of microbes and parasites, even at a very low concentration with very little systemic toxicity toward humans (Ouay and Stellacci, 2015). AgNPs have been reported to be used and tested for several applications including prevention of bacterial colonization and elimination of microorganisms on various medical devices, disinfection in wastewater treatment plants, and silicone rubber gaskets to protect and transport food and textile fabrics (Guzman et al., 2012).

The present study investigated synthesis of AgNPs using the waste leaves of ears of corn following a green route and evaluate its potential application as antibacterial compound against a number of five foodborne pathogenic bacteria (Bacillus cereus ATCC 13061, Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 19115, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 49444, Escherichia coli ATCC 43890, and Salmonella Typhimurium ATCC 43174) along with its anticandidal potential against five different Candida species (C. albicans KACC 30003 and KACC 30062, C. glabrata KBNO6P00368, C. geochares KACC 30061, and C. saitoana KACC 41238) and their antioxidant potentials. Utilization of these industrial waste materials in the synthesis of nanoparticles could add the values to the economy of industry.

Materials and Methods

Sample Preparation

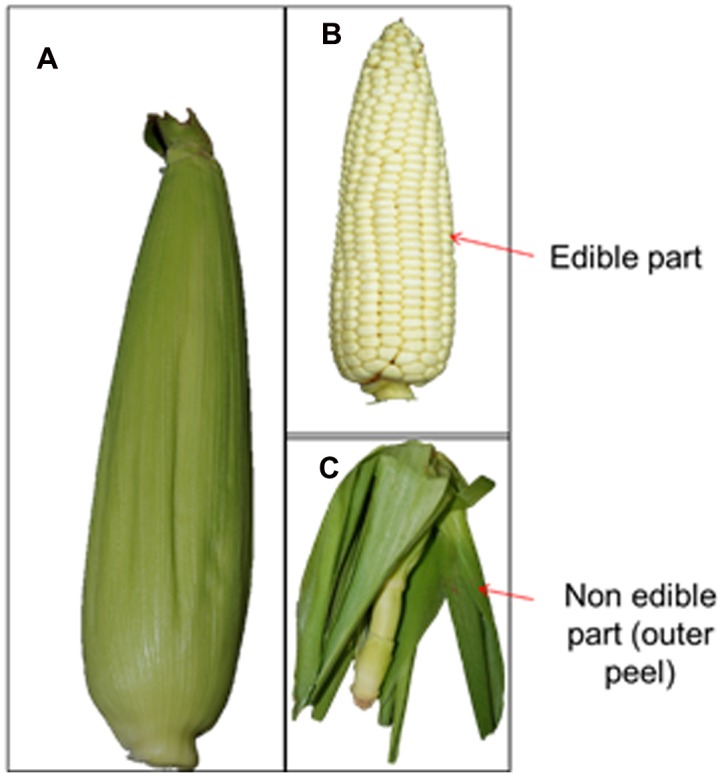

The whole corn of Z. mays L. (Figure 1A) was purchased from a local market located at Gyeonsan, Republic of Korea. The ear leaves (Figure 1C) were collected from the corn (Figures 1A,B) and cut into small pieces of approximately 1 cm. A total of 20 g of leaf pieces were then placed in a 250 mL conical flask, after which 100 mL of double distilled water was added and the samples were boiled for 15 min with continuous stirring. The aqueous extract of corn leaves (ACL) was cooled to room temperature, filtered and stored at 4°C before being used for the synthesis of AgNPs.

FIGURE 1.

Fruit (A), kernel (B), and non-edible leaves (C) of maize corn (Zea mays).

Biosynthesis of AgNPs

The synthesis of AgNPs was conducted by the green synthesis route using ACL. Briefly, 20 mL of ACL was added to 500 mL conical flasks containing 200 mL of 1 mM AgNO3 and stirred continuously at room temperature until the solution became reddish brown. The concentration of ACL to AgNO3 was maintained at 1:10 ratio with the use of less concentration of ACL and AgNO3 in order to control the shape and size of the nanoparticles.

Characterization of AgNPs

The newly synthesized AgNPs were characterized by UV-VIS spectroscopy, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), thermogravimetric and differential thermogravimetric (TGA/DTG) analysis, and X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) using standard analytical procedures (Basavegowda and Lee, 2013; Ramamurthy et al., 2013).

The synthesis of the AgNPs was monitored by the UV-Vis spectroscopy analysis by measuring the absorption spectra between 350 and 550 nm at a resolution of 1 nm using a microplate reader (Infinite 200 PRO NanoQuant, TECAN, Mannedorf, Switzerland). Changes in the color of the reaction mixture were observed every 3 h during incubation. The surface morphology of the AgNPs was analyzed using FE-SEM. The AgNPs were powdered using an agate mortar and pestle, then uniformly spread over the sample holder and sputter coated with platinum in an ion coater for 120 s, after which they were observed by FE-SEM (S-4200, Hitachi, Japan). Elemental composition analysis of the powdered AgNPs was conducted using an EDS detector (EDS, EDAX Inc., Mahwah, NJ, USA) attached to the FE-SEM machine. FT-IR analysis of the powdered AgNPs and the ACL extract was conducted using a FT-IR spectrophotometer (Jasco 5300, Jasco, Mary’s Court, Easton, MD, USA) in the wavelength range of 400–4000 cm-1. The powdered AgNPs sample was blended with potassium bromide (KBr) in a 1:100 ratio using an agate mortar and pestle, then compressed into a 2 mm semi-transparent disk using a specially designed screw knot, after which different modes of vibrations were analyzed for the presence of different types of functional groups in AgNPs and ACL extract.

Effects of high temperature on synthesized AgNPs were evaluated using a TGA machine (SDT Q600, TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA). For TGA analysis, powdered AgNPs (3.0 mg) were placed in an alumina pan and heated from 20 to 700°C at a ramping time of 10°C/min under a N2 atmosphere in a specially designed heating chamber. The corresponding weight loss data were recorded using a computer attached to the TG/DTG machine with the SDT software. The AgNPs nanoparticles were analyzed by XRD (X’Pert MRD model, PANalytical, Almelo, The Netherlands). Prior to use, the AgNPs were dried at 60°C in a vacuum oven and ground to fine powder using an agate mortar and pestle. The samples were uniformly spread over the glass sample holder and subsequently analyzed at 30 kV and 40 mA with Cu Kα radians at an angle of 2𝜃. The average particle diameter of AgNPs was calculated from the XRD pattern, according to the line width of the maximum intensity reflection peak. The size of the nanoparticles was calculated through the Scherer equation (Yousefzadi et al., 2014).

Biological Activity of AgNPs

Antibacterial Activity of AgNPs

The antibacterial potential of AgNPs was determined against five different foodborne bacteria (B. cereus ATCC 13061, L. monocytogenes ATCC 19115, S. aureus ATCC 49444, E. coli ATCC 43890, and S. Typhimurium ATCC 43174) by the standard disk diffusion method (Diao et al., 2013). The bacterial pathogens were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) and maintained on nutrient agar media (Difco, Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks Glencoe, MD, USA). Prior to use, the colloidal solution of the AgNPs was prepared by dissolving AgNPs in 5% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, 1000 μg/mL) and sonicating the samples at 30°C for 15 min. Filter paper disks containing 50 μg of AgNPs/disk were used for the assay. Standard antibiotics, kanamycin and rifampicin, at 5 μg/disk were taken as positive controls, while 5% DMSO was used as the negative control. The overnight grown cultures of tested bacteria were diluted to 1 × 10-7 colony forming unit were used for the assay. The antibacterial activity of the AgNPs was determined by measuring the diameter of zones of inhibition after 24 h of incubation at 37°C. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) of the AgNPs were determined by the two-fold serial dilution method (Kubo et al., 2004). Different concentrations of AgNPs (100–3.12 μg/mL) were used for MIC test. Prior to test, initially 200 μg of the AgNP was added to initial tube containing, 2 mL of NB media, then 1 mL from it was transferred to next tube which contains 1 mL of only NB media and mixed properly, then the dilution was made till the concentration of the last tube was 3.12 μg/mL. The control tube contains only 1 mL of NB media. Then 10 μL of the tested pathogen was added to each tube. This procedure was repeated for all the tested pathogens. Then all the tubes were mixed properly and were incubated at 37°C overnight in a shaker incubator. The lowest concentration of AgNPs that did not show any visible growth of test organisms was determined as the MIC. Further, the MIC concentration and the next higher concentration were spread on NA plates and incubated for another 24 h at 37°C. The concentration that did not show any growth of a single bacterial colony on the NA plates was defined as the MBC value. Both MIC and MBC values were expressed as μg/mL.

Synergistic Potential of AgNPs

The synergistic activity of the AgNPs was determined with antibiotics (kanamycin and rifampicin) or anticandidal agent (amphotericin b).

Synergistic antibacterial activity of AgNPs

The synergistic antibacterial potential of AgNPs, as well as kanamycin and rifampicin as a standard antibiotics was determined against five foodborne pathogenic bacteria, B. cereus ATCC 13061, E. coli ATCC 43890, L. monocytogenes ATCC 19115, S. aureus ATCC 49444, and S. Typhimurium ATCC 43174 by the standard disk diffusion method (Naqvi et al., 2013). The bacterial pathogens were freshly cultured on nutrient broth media (Difco, Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks Glencoe, MD, USA). AgNPs (1 mg/mL) and the standard antibiotics (kanamycin or rifampicin at 200 μg/mL) were mixed properly at a 1:1 ratio and sonicated for 15 min at room temperature. Different antibiotic disks were prepared by adding 50 μl of the AgNPs/antibiotics mixture solution to a 6 mm filter paper disk that contains 25 μg AgNPs and 5 μg antibiotics together. The synergistic antibacterial activity of the AgNPs/antibiotics mixture was measured after 24 h of incubation at 37°C in terms of the diameters of the zones of inhibition around the filter paper disks.

Synergistic anticandidal activity of AgNPs

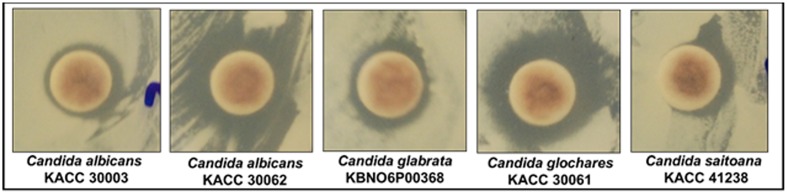

The synergistic anticandidal potentials of AgNPs and amphotericin b, a standard antifungal agent, were determined against five different pathogenic Candida species, C. albicans KACC 30003 and KACC 30062, C. glabrata KBNO6P00368, C. geochares KACC 30061 and C. saitoana KACC 41238, by the disk diffusion method (Murray et al., 1995). These Candida species were obtained from the Korean Agricultural Culture Collection (KACC, Suwon, Republic of Korea). AgNPs (2 mg/mL) and amphotericin b (200 μg/mL) were mixed in a 1:1 ratio and sonicated for 15 min at room temperature. Paper disks were prepared by adding 50 μL of the AgNPs/amphotericin b mixture solution to a 6 mm filter paper disk that contains 50 μg AgNPs and 5 μg amphotericin b. The Candida species in liquid media were spread uniformly on potato-dextrose agar (PDA) media (Difco, Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks Glencoe, MD, USA), after which the anticandidal disks were placed on the plates and samples were incubated at 28°C for 48 h. The synergistic anticandidal activity of the AgNPs/amphotericin b mixture solution was determined by measuring the diameters of the zones of inhibition around the paper disk.

Antioxidant Activity of AgNPs

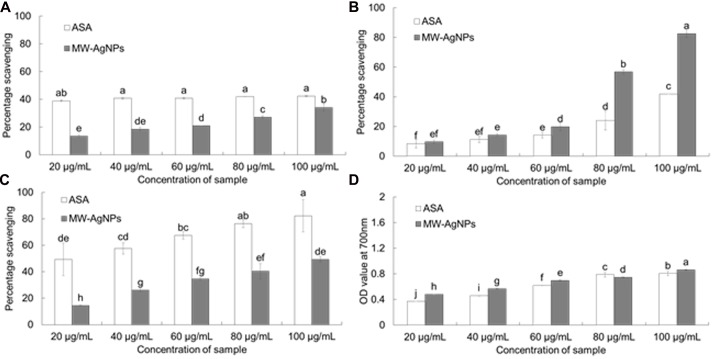

The antioxidant potential of the AgNPs was determined by 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging, nitric oxide (NO) scavenging, 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) (ABTS) radical scavenging and reducing power assays.

DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity of AgNPs

The DPPH free radical scavenging potential of AgNPs was determined as previously described (Patra et al., 2015). Briefly, five different concentrations (20–100 μg/mL) of AgNPs and ascorbic acid (ASA) as the standard reference compound was assayed. The absorbance of the reaction mixtures was recorded at 517 nm using the microplate reader and the results were interpreted as the percentage scavenging according to the following equation:

where, AbsC is the absorbance of the control and AbsT is the absorbance of the treatment.

NO Scavenging Activity of AgNPs

The NO scavenging potential of AgNPs was determined by the standard procedure (Makhija et al., 2011). Five different concentrations (20–100 μg/mL) of AgNPs and ASA as the standard reference compound were taken for the assay. The absorbance of the reaction mixtures was recorded at 546 nm using a microplate reader, after which the results were calculated as the percentage scavenging activity according to Eq. 1.

ABTS Radical Scavenging Activity of AgNPs

The ABTS radical scavenging potential of AgNPs was determined by the standard procedure (Thaipong et al., 2006). Briefly, five different concentrations (20–100 μg/mL) of AgNPs and ASA as the standard reference compound was taken for the assay. The absorbance of the reaction mixtures was recorded at 750 nm using a microplate reader, and the results were interpreted according to Eq. 1.

Reducing Power of AgNPs

The reducing power of AgNPs was determined by the standard procedure (Sun et al., 2011). Briefly, five different concentrations (20–100 μg/mL) of AgNPs and ASA as the standard reference compound were assayed. The absorbance of the reaction mixture was measured at 700 nm against an appropriate control and the results were expressed as OD values at 700 nm.

Statistical Analysis

The results of all the experiments were expressed as the mean value of three independent replicates ± the standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis of the significance differences between the mean values of the results were identified by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Duncan’s test at the 5% level of significance (P < 0.05) using the Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) (Version: SAS 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Synthesis of AgNPs

The industrial wastes from maize plants (Figures 1A,C) after utilization of the kernels (Figure 1B) were used in the present study for synthesis of AgNPs. Biosynthesis of AgNPs was indicated by gradual color development in the reaction solution after 1 h of incubation and subsequent increases in the intensity of the color during the course of reaction. The formation of AgNPs was monitored by a number of characterization techniques as described below.

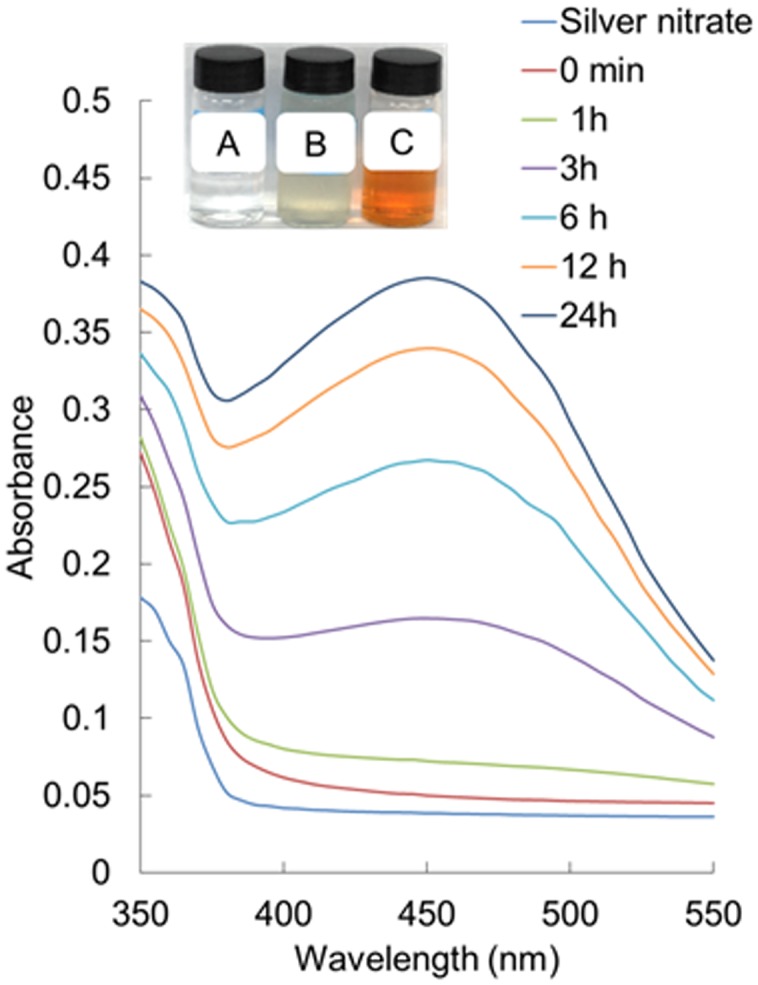

Characterization of AgNPs

The UV-Vis spectra of the synthesized AgNPs recorded at different time intervals are presented in Figure 2. The absorbance peaks indexed as different colors indicated the reduction of AgNO3 by ACL with different time intervals (0 min, 30 min, 1 h, 3 h, 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h) at room temperature (Figure 2). The UV-Vis spectra of the synthesized AgNPs were further recorded after 24 h, but the intensity of the color did not intensify after 24 h, confirming that the reaction was completed within 24 h.

FIGURE 2.

UV-visible spectra of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) synthesized by the aqueous corn leaves extracts (ACL). Inset: change in color of the solution confirming the synthesis of AgNPs (A – AgNO3 solution, B – aqueous corn leaves extracts (ACL), and C – AgNPs).

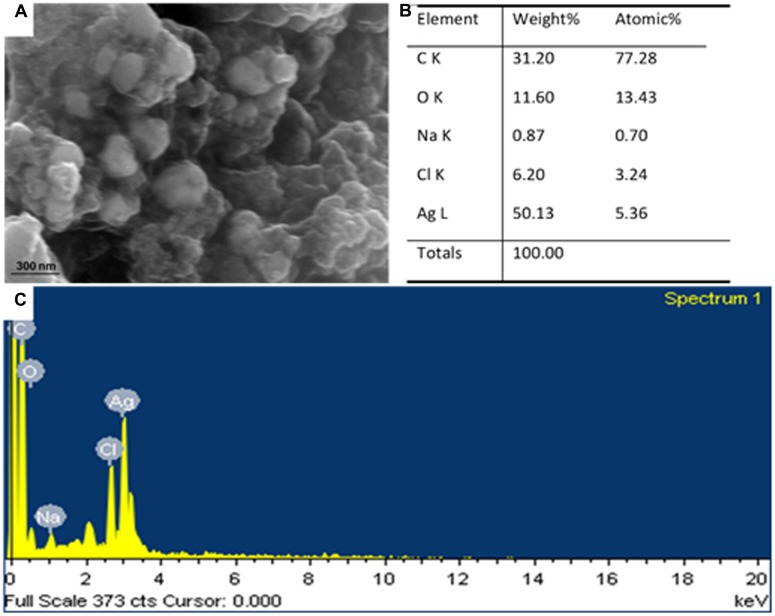

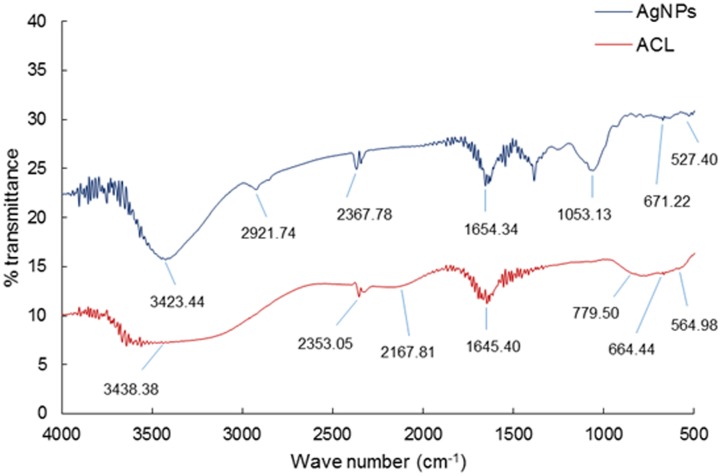

The morphology of the synthesized AgNPs was revealed by FE-SEM analysis (Figure 3A). The FE-SEM image revealed the formation of a cluster of spherical beadlike structures of AgNPs that were strongly aggregated. The elemental composition of the synthesized AgNPs was determined by an EDS machine attached to the FE-SEM. The elemental composition confirmed that AgNPs were composed of 50.13% Ag, 31.20% C, 11.60% O, 6.20% Cl, and 0.87% Na (Figures 3B,C). FT-IR analysis of the ACL and AgNPs is shown in Figure 4. Absorption peaks located at 3438.38, 2353.05, 2167.81, 1645.40, 779.50, 664.44, and 564.98 cm-1 were observed upon ACL, whereas absorption peaks located at 3423.44, 2921.74, 2367.78, 1654.34, 1053.13, 671.22, and 527.40 cm-1 were observed for the AgNPs (Figure 4).

FIGURE 3.

Scanning electron microscopy image (A) and energy-dispersive X-ray analysis (B,C) of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) synthesized by the aqueous extracts of corn leaves (ACL).

FIGURE 4.

Fourier-transformed infrared spectroscopy analysis of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) and the aqueous extracts of corn leaves (ACL).

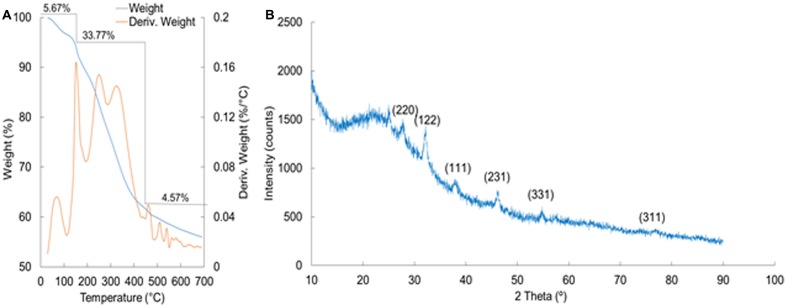

Thermogravimetric and differential thermogravimetric analysis of the synthesized AgNPs was conducted to show the nature of AgNPs at higher temperature (Figure 5A). A total of 44.01% weight loss was observed in three different phases when the AgNPs were heated to 700°C in a controlled N2 atmosphere. The first phase of weight loss was observed between 30 and 150°C with a weight loss of 5.67%. In this phase, the water molecules that were attached to the AgNPs during the course of synthesis were degraded. The second phase of weight loss was observed between 150 and 470°C with a maximum weight loss of 33.77%. During this phase, organic molecules, such as alkanes, phenols, alkenes, proteins, and polysaccharides from the ACL that contributed to the reduction of the AgNPs as capping and stabilizing agents were degraded. The third phase extended from 480 to 700°C, during which time there was a weight loss of 4.57%. The nature of the synthesized AgNPs was analyzed by XRD (Figure 5B). The diffraction pattern showed six diffraction peaks at 27.78°, 32.04°, 38.41°, 46.12°, 54.95°, and 76.78°, which corresponded to (220), (122), (111), (231), (331), and (311) planes of silver, respectively. The average crystal size of the silver crystallites was calculated from the full width at half maximum (FWHMs) values of the diffraction peaks, using the Scherer equation. The estimated size of crystallite in different planes of silver was determined as 31.18, 35.74, and 69.14 nm with the mean value of all three peaks as 45.26 nm.

FIGURE 5.

Thermogravimetric and differential thermogravimetric (TG/DTG) analysis (A) and X-ray diffraction analysis (B) of silver nanoparticles (PE-AgNPs) synthesized by the aqueous extracts of corn leaves (ACL).

Biological Activity of AgNPs

Antibacterial Activity of AgNPs

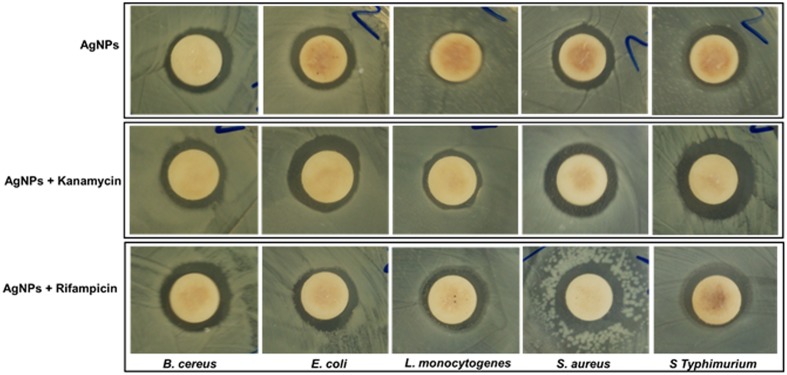

The AgNPs at 50 μg/disk displayed moderate antibacterial activity against all five foodborne pathogenic bacteria, as indicated by diameter of inhibition zones of 9.26–11.57 mm (Table 1; Figure 6). The standard antibiotics, kanamycin, and rifampicin, at 5 μg/disk did not show any inhibitory activity against any of the five pathogens. Among the pathogenic bacteria, AgNPs were more active against S. aureus (11.57 mm inhibition zone) than L. monocytogenes (9.26 mm inhibition zone). The MIC and the MBC values of AgNPs against all five pathogenic bacteria ranged from 12.5 to 100 μg/mL (Table 1).

Table 1.

Antibacterial activity of AgNPs against five foodborne pathogenic bacteria.

| Bacteria | AgNPs (50 μg/disk) | MIC (μg/mL) | MBC (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| B. cereus ATCC 13061 | 11.39 ± 1.2a∗ | 25 | 50 |

| E. coli ATCC 43890 | 10.55 ± 0.27b | 50 | 100 |

| L. monocytogenes ATCC 19115 | 9.26 ± 0.31c | 25 | 50 |

| S. aureus ATCC 49444 | 11.57 ± 0.25a | 12.5 | 25 |

| S. Typhimurium ATCC 43174 | 11.22 ± 0.38a | 50 | 100 |

∗Data are expressed as the mean zone of inhibition in mm ± SD. Values with different superscript letters are significantly different at P < 0.05.

FIGURE 6.

Antibacterial activity of AgNPs (50 μg/disk) and synergistic antibacterial potential of AgNPs (25 μg) mixed with standard antibiotics, kanamycin (5 μg), and rifampicin (5 μg).

Synergistic Antimicrobial Potentials of AgNPs

Synergistic antibacterial potential of AgNPs

The synergistic potential of the AgNPs together with the standard antibiotics, kanamycin and rifampicin, were evaluated against all five foodborne pathogenic bacteria and the results are presented in Table 2 and Figure 6. At low concentrations (5 μg/disk), neither antibiotics exhibited any positive activity against any of the five pathogenic bacteria, which was also true for AgNPs at 25 μg/disk concentration. Thus, to study the synergistic antibacterial potential, both antibiotics and AgNPs were combined at this low concentration and their activities were tested against the five foodborne pathogens. When both antibiotic and AgNPs were mixed, they displayed strong antibacterial activity against all pathogens, with zones of inhibition ranging in diameter from 10.62 to 14.33 mm (Table 2).

Table 2.

Synergistic antibacterial activity of AgNPs (25 μg) with standard antibiotics, kanamycin (5 μg) or rifampicin (5 μg), against foodborne pathogenic bacteria.

| Bacteria | AgNPs + Kanamycin | AgNPs + Rifampicin |

|---|---|---|

| B. cereus ATCC 13061 | 11.67 ± 0.16c∗ | 12.76 ± 0.44b |

| E. coli ATCC 43890 | 12.45 ± 2.02b | 11.43 ± 0.21c |

| L. monocytogenes ATCC 19115 | 10.62 ± 0.29d | 11.64 ± 0.23c |

| S. aureus ATCC 49444 | 12.57 ± 0.20b | 14.33 ± 0.40a |

| S. Typhimurium ATCC 43174 | 12.80 ± 0.31a | 11.45 ± 0.19c |

∗Data are expressed as the mean zone of inhibition in mm ± SD. Values in each same column with different superscript letters are significantly different at P < 0.05.

Synergistic anticandidal potential of AgNPs

The synergistic anticandidal activities of the AgNPs are presented in Table 3 and Figure 7. AgNPs at a concentration of 50 μg/mL did not exhibit any anticandidal activity against the five tested Candida species. However, when AgNPs (50 μg/disk) were combined with a standard anticandidal agent, amphotericin b (5 μg/disk), they displayed potent anticandidal activity against all five Candida species, with zones of inhibition ranging from 9.74 to 14.75 mm (Table 3; Figure 7).

Table 3.

Synergistic anticandidal activity of AgNPs (50 μg) with a standard antifungal agent, amphotericin b (5 μg), against pathogenic Candida species.

| Candida species | Mean inhibition zone in mm ±SD |

|---|---|

| C. albicans KACC 30003 | 10.34 ± 0.29cd∗ |

| C. albicans KACC 30062 | 12.88 ± 0.15b |

| C. glabrata KBNO6P00368 | 10.98 ± 0.71c |

| C. glochares KACC 30061 | 14.75 ± 0.30a |

| C. saitoana KACC 41238 | 9.74 ± 0.14d |

∗Values with different superscript letters are significantly different at P < 0.05.

FIGURE 7.

Synergistic anticandidal potential of AgNPs (50 μg) mixed with a standard amphotericin b (5 μg).

Antioxidant Activity of AgNPs

The antioxidant potential of synthesized AgNPs was determined by in vitro assays of DPPH radical scavenging, NO scavenging, ABTS radical scavenging and reducing power. The DPPH radical scavenging potential of AgNPs is presented in Figure 8A. AgNPs displayed a moderate DPPH radical scavenging potential of 34.09% at 100 μg/mL, whereas ASA, which was taken as the reference standard, showed comparably high DPPH scavenging activity of 42.41% at 100 μg/mL (Figure 8A). AgNPs exerted comparably high NO scavenging potential of 82.63% at 100 μg/mL compared with that of 41.95% of ASA at 100 μg/mL (Figure 8B). The ABTS radical scavenging potential of AgNPs is presented in Figure 8C. AgNPs exhibited a moderate value of 49.29% ABTS radical scavenging potential relative to 82.20% by ASA at 100 μg/mL. AgNPs also displayed strong reducing power (Figure 8D).

FIGURE 8.

Antioxidant potentials of AgNPs and ascorbic acid (ASA). (A) DPPH radical scavenging. (B) Nitric oxide scavenging. (C) ABTS radical scavenging. (D) Reducing power assay. Different superscript letters in each column indicate significant differences at P < 0.05.

Discussion

The concentration of ACL to AgNO3 was maintained at 1:10 ratio with the use of less concentration of ACL and AgNO3 in order to obtain small and controlled size of nanoparticles. It is presumed that less the concentration of the plant extracts and AgNO3 used, the smaller will be the size of the nanoparticles. This hypothesis has been proved by several researchers (Ghosh et al., 2011; Chandran et al., 2014) and can be confirmed again by the present study. The appearance of brown color in the reaction solution (Figure 2, inset) was a clear indication of the formation of AgNPs in the reaction mixture (Wu et al., 2004; Kumar et al., 2008; Kumari and Philip, 2013). The characterization of the synthesized AgNPs was achieved using techniques, such as UV-Vis spectroscopy, FE-SEM, EDS, FT-IR, TG/DTG analysis, and XRD analysis (Zhang et al., 2006; Choi et al., 2007; Vilchis-Nestor et al., 2008). These techniques are used for determination of different parameters, such as nature, particle size, characteristics, crystallinity, and surface area.

Spectral analysis revealed that the surface plasmon resonance phenomena (SPR) absorption maxima peak of the synthesized AgNPs occurred at 450 nm with a high absorbance value specific for AgNPs (Figure 2) (Kelly et al., 2003; Nazeruddin et al., 2014). In general, typical AgNPs show characteristic SPR at wavelengths ranging from 400 to 480 nm (Pal et al., 2007; Nazeruddin et al., 2014), which was also observed in the present investigation. The SPR absorbance is sensitive to the shape, size and nature of particles present in the solution, and also depends upon inner particle distance and the surrounding media (Nazeruddin et al., 2014). The surface morphology was seen by FE-SEM (Figure 3A) and its elemental composition by EDS analysis (Figures 3B,C). The EDS pattern indicates that the synthesized AgNPs were crystalline in nature, which is caused by the reduction of silver ions. A strong typical absorption peak was observed at 3.0 keV, which is typical of the absorption of metallic silver nanocrystallites due to SPR (Das et al., 2013) (Figure 3C). Similar results upon SEM and EDS analysis of different types of AgNPs were reported previously (Vijaykumar et al., 2013; Nazeruddin et al., 2014; Muthukrishnan et al., 2015; Velusamy et al., 2015).

The intense peaks in FT-IR spectra of both ACL and AgNPs (Figure 4) located at 3438 and 3423 cm-1 corresponded to O–H stretching of the alcohols and phenolic compounds, while the intense peaks at 1654 and 1645 cm-1 corresponded to – C=C-H stretching of the alkenes group (Ramamurthy et al., 2013; Rajeshkumar and Malarkodi, 2014). A major peak was observed at 2921 cm-1 in AgNPs, which could be assigned to the C-H stretching vibrations of methyl, methylene, and methoxy groups (Feng et al., 2009). The mechanism of adsorption and capping of AgNPs by ACL can be explained through the coordination of carbonyl bonds (3423 cm-1) and subsequent electron transfer from C=O to AgNPs (Qiu et al., 2006). The peak at 3423 cm-1 that corresponds to O-H stretching, 1654 cm-1 that corresponds to – C=C-H stretching of the alkenes group, and 1053 cm-1 might be contributed to by the C-O groups of the polysaccharides in the ACL extract that acted as reducing, capping, and stabilizing agents for the synthesis of AgNPs (Muthukrishnan et al., 2015). The slight shifting in the position of different peaks in the AgNPs from the ACL extract might have been due to progression of the reduction reaction with capping and stabilization of AgNPs by the various secondary metabolites present in the ACL. It is thus evident from the FT-IT spectra of the AgNPs that the bioactive compounds such are polyphenols (chlorogenic acid, caffeic acid, rutin, ferulic acid, morin, quercetin, naringenin, and kaempferol), anthocyanins, flavonoids, flavonols, and flavanols which were previously reported to be present in Z. mays (Ramos-Escudero et al., 2012; Bacchetti et al., 2013; Pandey et al., 2013) plays a vital role in the capping and stabilization of the AgNPs.

Thermogravimetric analysis of the AgNPs during this period (Figure 5A) indicated that the organic molecules from the ACL had mostly taken part in the synthesis and capping of the AgNPs, but were degraded at higher temperatures (Shaik et al., 2013). The nature of the synthesized AgNPs analyzed by XRD showed that the six diffraction peaks corresponded to (220), (122), (111), (231), (331), and (311) planes of silver, respectively, as per the standard FCC structures of Ag (JCPDS Card no. 04-0783) (Khurana et al., 2014; Roy et al., 2015). This structural characteristic pattern confirmed that the AgNPs had a crystalline structure. (Figure 5B).

The development of resistant pathogenic strains has recently affected healthcare systems worldwide (Rajeshkumar and Malarkodi, 2014). Therefore, the positive effects of AgNPs toward a number of foodborne pathogenic bacteria (Table 1) could be useful in formulation of new antibacterial drugs against resistant bacterial pathogens. Silver exhibits toxicity toward microorganisms but little or no toxicity toward animal cells; therefore, these properties of Ag particles could be more beneficial for AgNPs in the development of more potent drugs against the pathogens.

The exact cause of the antibacterial action of AgNPs against the pathogenic bacteria is not completely understood. Few studies have shown that the electrostatic attraction between negatively charged bacterial cells and the positively charged nanoparticles could be responsible for its bactericidal effects (Sondi and Salopek-Sondi, 2004). There are several possible proposed mechanisms for the positive antibacterial activity of AgNPs which includes the degradation of enzymes, inactivation of cellular proteins and breakage of DNA (Jiang et al., 2004; Sharma et al., 2009; Guzman et al., 2012). It is presumed that due to smaller size the AgNPs might have attached to the surface of the bacterial cell membrane and disturbed its power functions, such as permeability and respiration and then it could have easily penetrate to the inside of the bacteria and could have caused further damage, possibly by interacting with sulfur- and phosphorus-containing compounds, such as DNA resulting in cell lysis (Gibbins and Warner, 2005; Guzman et al., 2012; Singh et al., 2014; Yousefzadi et al., 2014; Ramesh et al., 2015; Swamy et al., 2015). Ovington (2004) reported the potential antimicrobial activity of nanocrystalline silver products by the process of releasing a cluster of highly reactive silver cations and radicals inside the pathogen body or the cell surface, this could be a possible reason for the antibacterial activity of AgNPs in the present study. The main possible mechanism of antimicrobial action of AgNPs could be that, due to the dissolution of AgNPs, antimicrobial Ag+ ions are released which can interact with sulfur-containing proteins in the bacterial cell wall, which may lead to compromised functionality (Levy, 1998; Lansdown, 2004; Ovington, 2004; Reidy et al., 2013).

Similarly, many authors have also reported that due to the smaller size, the interaction of the nanoparticles is better with the targeted pathogen and thus these were more effective (Panacek et al., 2006; Suriya et al., 2012). In addition to this, it is also believed that the AgNPs after penetration into the bacteria membrane might have inactivated their enzymes, generating hydrogen peroxide that ultimately resulted in the death of the bacteria (Raffi et al., 2008). Furthermore, it is also believed that the high affinity of silver for sulfur or phosphorus compounds could be a possible reason for its antibacterial activity against the pathogenic bacteria because as sulfur and phosphorus are abundantly found throughout the cell membrane, the AgNPs could have reacted with sulfur-containing proteins inside or outside the cell membrane and in turn affected the cell viability causing leakage of bacteria leading to lysis (Hamouda and Baker, 2000). Morones et al. (2005) have reported the presence of AgNPs not only at the surface of cell membrane, but also inside the bacteria using the scanning tunneling electron microscopy (STEM), this proves that due to their smaller size, AgNPs have penetrated inside the bacteria and fungi, causing damage by interacting with phosphorus- and sulfur-containing compounds such as DNA. It is evident that with the decrease in the size of the particles to the nanoscale range, the specific surface area of a dose of nanoparticles increases, which allows for greater material interaction with the surrounding environment such as the cell membrane of the targeted pathogenic bacteria. Thus for the inherently antibacterial materials, such as zinc and silver, increasing the surface to volume ratio enhances the antibacterial effect that results in positive antimicrobial activity due to a number of reasons, such as the release of antibacterial metal ions from the particle surface and the antibacterial physical properties of a nanoparticle related to cell wall penetration or membrane damage (Seil and Webster, 2012). It has also been reported that the crystallographic structure surface and high surface-to-volume ratio increase the contact area of metallic nanoparticles with the body of the microorganism that influences the antibacterial activity of nanosized silver particle (Kora and Arunachalam, 2011). These properties of AgNPs made it a potential candidate for the industries in development of modern antimicrobial products. Moreover, the AgNPs could be useful in the formulation of polymer materials for packaging of food items and other durable materials that could be affected by microorganisms (Rhim and Ng, 2007; Finnigan, 2009).

Further study on the synergistic antibacterial activity of AgNPs with the antibiotics that showed as strong positive result (Table 2) could be due to the easy penetration of the mixture solution into the bacterial cell membrane, causing serious damage to the cells and death of the bacteria. This synergistic potential of AgNPs with the antibiotics could help minimize the extensive use of antibiotics that has resulted in development of many antibiotic resistant strains. Previously, the positive synergism impact of nanoparticle-antibiotics combination at significantly low concentration have been demonstrated against a number of dreadful multi-drug resistant pathogenic bacteria (Li et al., 2005; Birla et al., 2009; Ruden et al., 2009; Fayaz et al., 2010; Hwang et al., 2012; McShan et al., 2015; Barapatre et al., 2016; Deng et al., 2016; Panacek et al., 2016). All these authors have proposed that such positive results of nanoparticle-antibiotics combination might be due to the differences in size of prepared Ag-NPs the bonding reaction between them which enable the mixture to better interact with the pathogen.

Similarly, the synergistic anticandidal activities of the AgNPs as presented in Table 3 and Figure 7 confirmed that the use of AgNPs together with lower concentrations of anticandidal agents could be beneficial in clinical applications by enabling the application of lower amounts of anticandidal agents to avoid adverse effects and development of drug resistant pathogens (Gajbhiye et al., 2009). Candida are among the most common pathogenic yeast influencing humans, but treatments for Candida infections are limited because of development of resistant Candida sp., limited availability of antifungal drugs and high costs (Khan et al., 2003). Thus, the use of AgNPs together with low concentrations of amphotericin b has the potential for improved treatment of Candida related diseases. There have been only several reports on the antibacterial effect of AgNPs against Candida sp. (Panacek et al., 2009; Vazquez-Munoz et al., 2014; Artunduaga Bonilla et al., 2015; Lara et al., 2015), and the present study also corroborates with previous claim. As a previous report of the effective synergistic effects of AgNPs combined with antibiotics (Monteiro et al., 2013), the present study also corroborates with their findings.

The strong antioxidant potential of the AgNPs (Figure 8), could also make it a good source of natural agent for antioxidant. The strong DPPH and NO scavenging potential of AgNPs could make it a potential candidate for drug delivery. The moderate ABTS scavenging potential of AgNPs compared to ASA might be due to the different types of functional groups from the ACL that have attached to the surface of AgNPs during synthesis and capping of AgNPs (Adedapo et al., 2008). AgNPs also displayed strong reducing power, which might be attributed to the presence of phenolic compounds from ACL extract on the surface of AgNPs as surface stabilizers and capping agents. It is observed in the present investigation that the antioxidant activity of the AgNPs was higher than that of the standard ASA which might be possible due to the size and crystalline nature of the AgNPs as reported by various authors (El-Rafie and Abdel-Aziz Hamed, 2014; Bhakya et al., 2016; Gopukumar et al., 2016).

Conclusion

In the present study, AgNPs were synthesized using the aqueous extract of Z. mays corn leaves, which is a novel approach of waste utilization in nanoparticle synthesis. The results revealed that the synthesized nanoparticles are within the nanometer range, with an SPR of 450 nm based on UV-Vis spectroscopy. The elemental composition and crystallinity structure confirmed the synthesized particles to be Ag. The AgNPs displayed positive antibacterial activity against different foodborne pathogenic bacteria, as well as strong synergistic antibacterial and anticandidal activity with low concentrations of antibiotics and anticandidal agents. The AgNPs exhibited strong antioxidant potential. Based on these results, this approach of utilization of industrial wastes in nanoparticle synthesis can be beneficial in large scale fabrication of nanomaterials. The synergistic study of AgNPs with common antibiotics and anticandidal agents could be beneficial in formulation of antibacterial products and anticandidal drugs to be used in various food, agricultural, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical industries and future platforms for preparing nano-medicines, and targeted drug delivery.

Author Contributions

JP carried out all the experiment and wrote the manuscript. JP and K-HB designed and edited the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Systems and Synthetic Agro-biotech Center through the Next-Generation Bio-Green 21 Program (PJ011117), Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

References

- Adedapo A. A., Jimoh F. O., Afolayan A. J., Masika P. J. (2008). Antioxidant activities and phenolic contents of the methanol extracts of the stems of Acokanthera oppositifolia and Adenia gummifera. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 8:54 10.1186/1472-6882-8-54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson D. I., Hughes D. (2010). Antibiotic resistance and its cost: Is it possible to reverse resistance? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8 260–271. 10.1038/nrmicro2319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artunduaga Bonilla J. J., Paredes-Guerrero D. J., Sanchez-Suarez C. I., Ortiz-Lopez C. C., Torres-Saez R. G. (2015). In vitro antifungal activity of silver nanoparticles against fluconazole resistant Candida species. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 31 1801–1809. 10.1007/s11274-015-1933-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacchetti T., Masciangelo S., Micheletti A., Ferretti G. (2013). Carotenoids, phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity of five local Italian corn (Zea mays L.) kernels. J. Nutr. Food Sci. 3:6 10.4172/2155-9600.1000237 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barapatre A., Aadil K. R., Jha H. (2016). Synergistic antibacterial and antibiofilm activity of silver nanoparticles biosynthesized by lignin-degrading fungus. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 3:8 10.1186/s40643-016-0083-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Basavegowda N., Lee Y. R. (2013). Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Satsuma mandarin (Citrus unshiu) peel extract: a novel approach towards waste utilization. Mater. Lett. 109 31–33. 10.1016/j.matlet.2013.07.039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhakya S., Muthukrishnan S., Sukumaran M., Grijalva M., Cumbal L., Franklin-Benjamin J. H., et al. (2016). Antimicrobial, antioxidant and anticancer activity of biogenic silver nanoparticles – an experimental report. RSC Adv. 6 81436–81446. 10.1039/C6RA17569D [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Birla S. S., Tiwari V. V., Gade A. K., Ingle A. P., Yadav A. P., Rai M. K. (2009). Fabrication of silver nanoparticles by Phoma glomerata and its combined effect against Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 48 173–179. 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2008.02510.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandran K., Song S., Yun S. I. (2014). Effect of size and shape controlled biogenic synthesis of gold nanoparticles and their mode of interactions against food borne bacterial pathogens. Arabian J. Chem. 10.1016/j.arabjc.2014.11.041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y., Ho N., Tung C. (2007). Sensing phosphatase activity by using gold nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 46 707–709. 10.1002/anie.200603735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das J., Paul Das M., Velusamy P. (2013). Sesbania grandiflora leaf extract mediated green synthesis of antibacterial silver nanoparticles against selected human pathogens. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 104 265–270. 10.1016/j.saa.2012.11.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng H., McShan D., Zhang Y., Sinha S. S., Arslan Z., Ray P. C., et al. (2016). Mechanistic study of the synergistic antibacterial activity of combined silver nanoparticles and common antibiotics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50 8840–8848. 10.1021/acs.est.6b00998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devi L. S., Joshi S. R. (2012). Antimicrobial and synergistic effects of silver nanoparticles synthesized using soil fungi of high altitudes of eastern Himalaya. Mycobiology 40 27–34. 10.5941/MYCO.2012.40.1.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diao W. R., Hu Q. P., Feng S. S., Li W. Q., Xu J. G. (2013). Chemical composition and antibacterial activity of the essential oil from green huajiao (Zanthoxylum schinifolium) against selected foodborne pathogens. J. Agric. Food Chem. 61 6044–6049. 10.1021/jf4007856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Rafie H. M., Abdel-Aziz Hamed M. (2014). Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of silver nanoparticles biosynthesized from aqueous leaves extracts of four Terminalia species. Adv. Nat. Sci. 5:035008. [Google Scholar]

- Fayaz A. M., Balaji K., Girilal M., Yadav R., Kalaichelvan P. T., Venketesan R. (2010). Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their synergistic effect with antibiotics: a study against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. J. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. 6 103–109. 10.1016/j.nano.2009.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng N., Guo X., Liang S. (2009). Adsorption study of copper (II) by chemically modified orange peel. J. Hazard. Mater. 164 1286–1292. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.09.096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnigan B. (2009). “Barrier polymers,” in The Wiley Encyclopedia of Packaging Technology, ed. Yam K. L. (New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; ), 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Gajbhiye M., Kesharwani J., Ingle A., Gade A., Rai M. (2009). Fungus-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their activity against pathogenic fungi in combination with fluconazole. Nanomedicine 5 382–386. 10.1016/j.nano.2009.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geddes J. R., Carney S. M., Davies C., Furukawa T. A., Kupfer D. J., Frank E., et al. (2003). Relapse prevention with antidepressant drug treatment in depressive disorders: a systematic review. Lancet 361 653–661. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12599-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh P. K., Saxena T. K., Gupta R., Yadav R. P., Davidson S. (1996). Microbial lipases: production and applications. Sci. Prog. 79 119–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S., Patil S., Ahire M., Kitture R., Jabgunde A., Kale S., et al. (2011). Synthesis of gold nanoanisotrops using Dioscorea bulbifera tuber extract. J. Nanomater. 45 1–8. 10.1155/2011/354793 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbins B., Warner L. (2005). The role of antimicrobial silver nanotechnology. Med. Device Diagn. Ind. Mag. 1 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Gopinath V., MubarakAli D., Priyadarshini S., Priyadharsshini N. M., Thajuddin N., Velusamy P. (2012). Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles from Tribulus terrestris and its antimicrobial activity: a novel biological approach. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 96 69–74. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopukumar S. T., Sana-Fathima T. K., Alexander P., Alex V., Praseetha P. K. (2016). Evaluation of antioxidant properties of silver nanoparticle embedded medicinal patch. Nanomed. Nanotech. Op. Acc. 1:NNOA-MS-ID-000101. [Google Scholar]

- Guzman M., Dille J., Godet S. (2012). Synthesis and antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 8 37–45. 10.1016/j.nano.2011.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamouda T., Baker J. R., Jr. (2000). Antimicrobial mechanism of action of surfactant lipid preparations in enteric gram-negative bacilli. J. Appl. Microbiol. 89 397–403. 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.01127.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh A. J., Kwon Y. J. (2011). “Nanoantibiotics”: a new paradigm for treating infectious diseases using nanomaterials in the antibiotics resistant era. J. Control. Release 156 128–145. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang I., Hwang J. H., Choi H., Kim K. J., Lee D. G. (2012). Synergistic effects between silver nanoparticles and antibiotics and the mechanisms involved. J. Med. Microbiol. 61 1719–1726. 10.1099/jmm.0.047100-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain P. K., Huang X., El-Sayed I. H., El-Sayed M. A. (2008). Noble metals on the nanoscale: optical and photothermal properties and some applications in imaging, sensing, biology, and medicine. Acc. Chem. Res. 41 1578–1586. 10.1021/ar7002804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H., Manolache S., Lee-Wong C., Denis F. S. (2004). Plasma-enhanced deposition of silver nanoparticles onto polymer and metal surfaces for the generation of antimicrobial characteristics. J. Appl. Polymer Sci. 93 1411–1422. 10.1002/app.20561 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly K. L., Coronado E., Zhao L. L., Schatz G. C. (2003). The optical properties of metal nanoparticles: the influence of size, shape, and dielectric environment. J. Phys. Chem. B 107 668–677. 10.1021/jp026731y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khan Z. U., Chandy R., Metwali K. E. (2003). Candida albicans strain carriage in patients and nursing staff of an intensive care unit: a study of morphotypes and resistotypes. Mycoses 46 476–486. 10.1046/j.0933-7407.2003.00929.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khurana C., Vala A. K., Andhariya N., Pandey O. P., Chudasama B. (2014). Antibacterial activities of silver nanoparticles and antibiotic-adsorbed silver nanoparticles against biorecycling microbes. Environ. Sci. Proc. Impact 16 2191–2198. 10.1039/c4em00248b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstantopoulou M. A., Krokos F. D., Mazomenos B. E. (2004). Chemical composition of corn leaf essential oils and their role in the oviposition behavior of Sesamia nonagrioides females. J. Chem. Ecol. 30 2243–2256. 10.1023/B:JOEC.0000048786.12136.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kora A. J., Arunachalam J. (2011). Assessment of antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles on Pseudomonas aeruginosa and its mechanism of action. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 27 1209–1216. 10.1007/s11274-010-0569-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo I., Fujita K., Kubo A., Nihei K., Ogura T. (2004). Antibacterial activity of coriander volatile compounds against Salmonella choleraesuis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 52 3329–3332. 10.1021/jf0354186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Vemula P. K., Ajayan P. M., John G. (2008). Silver-nanoparticle-embedded antimicrobial paints based on vegetable oil. Nat. Mater. 7 236–241. 10.1038/nmat2099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V., Yadav S. K. (2009). Plant-mediated synthesis of silver and gold nanoparticles and their applications. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 84 151–157. 10.1002/jctb.2023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari M. M., Philip D. (2013). Facile one-pot synthesis of gold and silver nanocatalysts using edible coconut oil. Spectrochim. Acta A. Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 111 154–160. 10.1016/j.saa.2013.03.076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansdown A. B. G. (2004). A review of the use of silver in wound care: facts and fallacies. Br. J. Nurs. 13 6–19. 10.12968/bjon.2004.13.Sup1.12535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara H. H., Garza-Trevino E. N., Ixtepan-Turrent L., Singh D. K. J. (2011). Silver nanoparticles are broad-spectrum bactericidal and virucidal compounds. J. Nanobiotechnol. 9:30 10.1186/1477-3155-9-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara H. H., Romero-Urbina D. G., Pierce C., Lopez-Ribot J. L., Arellano-Jimenez M. J., Jose-Yacaman M. (2015). Effect of silver nanoparticles on Candida albicans biofilms: an ultrastructural study. J. Nanobiotechnol. 13:91 10.1186/s12951-015-0147-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy S. B. (1998). The challenge of antibiotic resistance. Sci. Am. 3 32–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P., Li J., Wu C., Wu Q., Li J. (2005). Synergistic antibacterial effects of β-lactam antibiotic combined with silver nanoparticles. Nanotechnology 16:1912. 10.1088/0957-4484/16/9/082 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Makhija I. K., Aswatha-Ram H. N., Shreedhara C. S., Vijay Kumar S., Devkar R. (2011). In vitro antioxidant studies of sitopaladi churna, a polyherbal ayurvedic formulation. Free Radic. Antioxid. 1 37–41. 10.5530/ax.2011.2.8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marini M., De Niederhausern N., Iseppi R., Bondi M., Sabia C., Toselli M., et al. (2007). Antibacterial activity of plastics coated with silver-doped organic-inorganic hybrid coatings prepared by sol–gel processes. Biomacromolecules 8 1246–1254. 10.1021/bm060721b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matei A., Cernica I., Cadar O., Roman C., Schiopu V. (2008). Synthesis and characterization of ZnO-polymer nanocomposites. Int. J. Mater. Form. 1 767–770. 10.1007/s12289-008-0288-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McShan D., Zhang Y., Deng H., Ray P. C., Yu H. (2015). Synergistic antibacterial effect of silver nanoparticles combined with ineffective antibiotics on drug resistant Salmonella typhimurium DT104. J. Environ. Sci. Health. C Environ. Carcinog. Ecotoxicol. Rev. 33 369–384. 10.1080/10590501.2015.1055165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohanpuria P., Rana N. K., Yadav S. K. (2008). Biosynthesis of nanoparticles: technological concepts and future applications. J. Nanopart. Res. 10 507–517. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06927.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro D. R., Silva S., Negri M., Gorup L. F., de Camargo E. R., Oliveira R., et al. (2013). Antifungal activity of silver nanoparticles in combination with nystatin and chlorhexidine digluconate against Candida albicans and Candida glabrata biofilms. Mycoses 56 672–680. 10.1111/myc.12093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morones J., Elechiguerra J., Camacho A., Holt K., Kouri J., Ramirez J., et al. (2005). The bactericidal effect of silver nanoparticles. Nanotechnology 16k2346–2353. 10.1088/0957-4484/16/10/059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray P. R., Baron E. J., Pfaller M. A., Tenover F. C., Yolke R. H. (1995). Manual of Clinical Microbiology, 6th Edn. Washington, DC: ASM Press. [Google Scholar]

- Muthukrishnan S., Bhakya S., Senthil Kumar T., Rao M. V. (2015). Biosynthesis, characterization and antibacterial effect of plant-mediated silver nanoparticles using Ceropegia thwaitesii – an endemic species. Ind. Crop. Prod. 63 119–124. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2014.10.022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nair L. S., Laurencin C. T. (2007). Silver nanoparticles: synthesis and therapeutic applications. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 3 301–316. 10.1166/jbn.2007.041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naqvi S. Z. H., Kiran U., Ali M. I., Jamal A., Hameed A., Ahmed S., et al. (2013). Combined efficacy of biologically synthesized silver nanoparticles and different antibiotics against multidrug-resistant bacteria. Int. J. Nanomed. 8 3187–3195. 10.2147/IJN.S49284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan K., Selvaraj S., Ramachandra M. V. (2010). Microbial production of silver nanoparticles. Dig. J. Nanomater. Biostruct. 5 135–140. [Google Scholar]

- Nazeruddin G. M., Prasad N. R., Prasad S. R., Shaikh Y. I., Waghmare S. R., Adhyapakca P. (2014). Coriandrum sativum seed extract assisted in situ green synthesis of silver nanoparticle and its anti-microbial activity. Ind. Crop. Prod. 60 212–216. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2014.05.040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nezamdoost T., Bagherieh-Najjarn M. B., Aghdasi M. (2014). Biogenic synthesis of stable bioactive silver chloride nanoparticles using Onosma dichroantha Boiss. root extract. Mater. Lett. 137 225–228. 10.1016/j.matlet.2014.08.134 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ouay B., Stellacci F. (2015). Antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles: a surface science insight. Nano Today 10 339–354. 10.1016/j.nantod.2015.04.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ovington L. G. (2004). The truth about silver. Ostomy Wound Manage. 50 1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal S., Tak Y. K., Song J. M. (2007). Does the antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles depend on the shape of the nanoparticle? A study of the Gram-negative bacterium Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73 1712–1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panacek A., Kolar M., Vecerova R., Prucek R., Soukupova J., Krystof V., et al. (2009). Antifungal activity of silver nanoparticles against Candida spp. Biomaterials 30 6333–6340. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panacek A., Kvitek L., Prucek R., Kolar M., Vecerova R., Pizurova N., et al. (2006). Silver colloid nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization, and their antibacterial activity. J. Phys. Chem. B 110 16248–16253. 10.1021/jp063826h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panacek A., Smekalova M., Kilianova M., Prucek R., Bogdanova K., Vecerova R., et al. (2016). Strong and nonspecific synergistic antibacterial efficiency of antibiotics combined with silver nanoparticles at very low concentrations showing no cytotoxic effect. Molecules 21:26 10.3390/molecules21010026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey R., Singh A., Maurya S., Singh U. P., Singh M. (2013). Phenolic acids in different preparations of Maize (Zea mays) and their role in human health. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2 84–92. [Google Scholar]

- Patra J. K., Kim S. H., Baek K. H. (2015). Antioxidant and free radical-scavenging potential of essential oil from Enteromorpha linza L. prepared by microwave-assisted hydrodistillation. J. Food Biochem. 39 80–90. 10.1111/jfbc.12110 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu L., Liu F., Zhao L., Yang W., Yao J. (2006). Evidence of a unique electron donor-acceptor property for platinum nanoparticles as studied by XPS. Langmuir 22 4480–4482. 10.1021/la053071q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffi M., Hussain F., Bhatti T. M., Akhter J. I., Hameed A., Hasan M. M. (2008). Antibacterial characterization of silver nanoparticles against E. coli ATCC-15224. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 24 192–196. [Google Scholar]

- Rai M. K., Deshmukh S. D., Ingle A. P., Gade A. K. (2012). Silver nanoparticles: the powerful nanoweapon against multidrug-resistant bacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 112 841–852. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2012.05253.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajeshkumar S., Malarkodi C. (2014). In vitro antibacterial activity and mechanism of silver nanoparticles against foodborne pathogens. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2014 1–10. 10.1155/2014/581890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramamurthy C. H., Padma M., Daisy mariya samadanam I., Mareeswaran R., Suyavaran A., Suresh Kumar M., et al. (2013). The extra cellular synthesis of gold and silver nanoparticles and their free radical scavenging and antibacterial properties. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 102 808–815. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh P. S., Kokila T., Geetha D. (2015). Plant mediated green synthesis and antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles using Emblica officinalis fruit extract. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 142 339–343. 10.1016/j.saa.2015.01.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Escudero F., Munoz A. M., Alvarado-Ortiz C., Alvarado A., Yanez J. A. (2012). Purple corn (Zea mays L.) phenolic compounds profile and its assessment as an agent against oxidative stress in isolated mouse organs. J. Med. Food. 15 206–215. 10.1089/jmf.2010.0342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reidy B., Haase A., Luch A., Dawson K. A., Lynch I. (2013). Mechanisms of silver nanoparticle release, transformation and toxicity: a critical review of current knowledge and recommendations for future studies and applications. Materials 6 2295–2350. 10.3390/ma6062295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhim J. W., Ng P. K. W. (2007). Natural biopolymer-based nanocomposite films for packaging applications. Crit. Rev. Food. Sci. 47 411–433. 10.1080/10408390600846366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy K., Sarkar C. K., Ghosh C. K. (2015). Photocatalytic activity of biogenic silver nanoparticles synthesized using potato (Solanum tuberosum) infusion. Spectrochem. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 146 286–291. 10.1016/j.saa.2015.02.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruden S., Hilpert K., Berditsch M., Wadhwani P., Ulrich A. S. (2009). Synergistic interaction between silver nanoparticles and membrane-permeabilizing antimicrobial peptides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53 3538–3540. 10.1128/AAC.01106-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena A., Tripathi R. M., Zafar F., Singh P. (2012). Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous solution of Ficus benghalensis leaf extract and characterization of their antibacterial activity. Mater. Lett. 67 91–94. 10.1016/j.matlet.2011.09.038 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seil J. T., Webster T. J. (2012). Antimicrobial applications of nanotechnology: methods and literature. Int. J. Nanomed. 7 2767–2781. 10.2147/IJN.S24805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahverdi A. R., Fakhimi A., Shahverdi H. R., Minaian M. S. (2007). Synthesis and effect of silver nanoparticles on the antibacterial activity of different antibiotics against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 3 168–171. 10.1016/j.nano.2007.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaik S., Kummara M. R., Poluru S., Allu C., Gooty J. M., Kashayi C. R., et al. (2013). A green approach to synthesize silver nanoparticles in starch-co-poly(acrylamide) hydrogels by Tridax procumbens leaf extract and their antibacterial activity. Int. J. Carbohydrate. Chem. 2013:539636 10.1155/2013/539636 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma V. K., Yngard R. A., Lin Y. (2009). Silver nanoparticles: green synthesis and their antimicrobial activities. Adv. Colloid Interface. Sci. 145 83–96. 10.1016/j.cis.2008.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh K., Panghal M., Kadyan S., Chaudhary U., Yadav J. P. (2014). Antibacterial activity of synthesized silver nanoparticles from Tinospora cordifolia against multi drug resistant strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from burn patients. J. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. 5:192 10.4172/2157-7439.1000192 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Solihah M. A., Wan Rosli W. I., Nurhanan A. R. (2012). Phytochemicals screening and total phenolic content of Malaysian Zea mays hair extracts. Int. Food Res. J. 19 1533–1538. [Google Scholar]

- Sondi I., Salopek-Sondi B. (2004). Silver nanoparticles as antimicrobial agent: a case study on E. coli as a model for gram-negative bacteria. J. Colloid Interface. Sci. 275 177–182. 10.1016/j.jcis.2004.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L., Zhang J., Lu X., Zhang L., Zhang Y. (2011). Evaluation to the antioxidant activity of total flavonoids extract from persimmon (Diospyros kaki L.) leaves. Food Chem. Toxicol. 49 2689–2696. 10.1016/j.fct.2011.07.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suriya J., Bharathi-Raja S., Sekar V., Rajasekaran R. (2012). Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles and its antibacterial activity using seaweed Urospora sp. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 11 12192–12198. 10.5897/AJB12.452 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swamy M. K., Mohanty S. K., Jayanta K., Subbanarasiman B. (2015). The green synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of the biological activities of silver nanoparticles synthesized from Leptadenia reticulata leaf extract. Appl. Nanosci. 5 73–81. 10.1007/s13204-014-0293-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thaipong K., Boonprakob U., Crosby K., Cisneros-Zevallos L., Byrne D. H. (2006). Comparison of ABTS, DPPH, FRAP, and ORAC assays for estimating antioxidant activity from guava fruit extracts. J. Food Comp. Anal. 19 669–675. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah I., Ali M., Farooqi A. (2010). Chemical and nutritional properties of some maize (Zea mays L.) varieties grown in NWFP, Pakistan. Pakistan J. Nutr. 9 1113–1117. 10.3923/pjn.2010.1113.1117 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valli J. S., Vaseeharan B. (2012). Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles by Cissus quadrangularis extracts. Mater. Lett. 82 171–173. 10.1016/j.matlet.2012.05.040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez-Munoz R., Avalos-Borja M., Castro-Longoria E. (2014). Ultrastructural analysis of Candida albicans when exposed to silver nanoparticles. PLoS ONE 9:e108876 10.1371/journal.pone.0108876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velusamy P., Das J., Pachaiappan R., Vaseeharan B., Pandian K. (2015). Greener approach for synthesis of antibacterial silver nanoparticles using aqueous solution of neem gum (Azadirachta indica L.). Ind. Crop. Prod. 66 103–109. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2014.12.042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vijaykumar M., Priya K., Nancy F. T., Noorlidah A., Ahmad A. B. A. (2013). Biosynthesis, characterization and anti-bacterial effect of plant-mediated silver nanoparticles using A. Nilgirica. Ind. Crops Prod. 41 235–240. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.04.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vilchis-Nestor A. R., Sanchez-Mendieta V., Camacho-Lopez M. A., Gomez-Espinosa R. M., Camacho-Lopez M. A., Arenas-Alatorre J. A. (2008). Solvent less synthesis and optical properties of Au and Ag nanoparticles using Camellia sinensis extract. Mater. Lett. 62 3103–3105. 10.1016/j.matlet.2008.01.138 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu N., Fu L., Aslam M., Wong K. C., Dravid V. W. (2004). Interaction of fatty acid monolayers with cobalt nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 4 383–386. 10.1021/nl035139x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yousefzadi M., Rahimi Z., Ghafori V. (2014). The green synthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activities of silver nanoparticles synthesized from green alga Enteromorpha flexuosa (wulfen) J. Agardh. Mater. Lett. 137 1–4. 10.1016/j.matlet.2014.08.110 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zargar M., Shameli S., Reza Najafi G., Farahani F. (2014). Plant mediated green biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Vitex negundo L. extract. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 20 4169–4175. 10.3390/molecules16086667 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L. Z., Yu J. C., Yip H. Y., Li Q., Kwong K. W., Xu A. W., et al. (2003). Ambient light reduction strategy to synthesize silver nanoparticles and silver coated TiO2 with enhanced photocatalytic and bactericidal activities. Langmuir 19 10372–10380. 10.1021/la035330m [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Qiao X., Chen J., Wang H. (2006). Preparation of silver nanoparticles in water-in-oil AOT reverse micelles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 302 370–373. 10.1016/j.jcis.2006.06.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]