Abstract

Introduction

The Merck Adenovirus-5 Gag/Pol/Nef HIV-1 subtype-B vaccine evaluated in predominately subtype B epidemic regions (Step Study), while not preventing infection, exerted vaccine-induced immune pressure on HIV-1 breakthrough infections. Here we investigated if the same vaccine exerted immune pressure when tested in the Phambili Phase 2b study in a subtype C epidemic.

Materials and methods

A sieve analysis, which compares breakthrough viruses from placebo and vaccine arms, was performed on 277 near full-length genomes generated from 23 vaccine and 20 placebo recipients. Vaccine coverage was estimated by computing the percentage of 9-mers that were exact matches to the vaccine insert.

Results

There was significantly greater protein distances from the vaccine immunogen sequence in Gag (p = 0.045) and Nef (p = 0.021) in viruses infecting vaccine recipients compared to placebo recipients. Twenty-seven putative sites of vaccine-induced pressure were identified (p < 0.05) in Gag (n = 10), Pol (n = 7) and Nef (n = 10), although they did not remain significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons. We found the epitope sieve effect in Step was driven by HLA A*02:01; an allele which was found in low frequency in Phambili participants compared to Step participants. Furthermore, the coverage of the vaccine against subtype C Phambili viruses was 31%, 46% and 14% for Gag, Pol and Nef, respectively, compared to subtype B Step virus coverage of 56%, 61% and 26%, respectively.

Discussion

This study presents evidence of sieve effects in Gag and Nef; however could not confirm effects on specific amino acid sites. We propose that this weaker signal of vaccine immune pressure detected in the Phambili study compared to the Step study may have been influenced by differences in host genetics (HLA allele frequency) and reduced impact of vaccine-induced immune responses due to mismatch between the viral subtype in the vaccine and infecting subtypes.

Keywords: HIV-1 vaccine, Phambili, Step, Sieve analysis, HVTN-503

1. Introduction

Sieve analysis, which compares breakthrough viruses from placebo and vaccine arms, is a powerful tool for elucidating mechanisms of vaccine protection. There are two types of sieve effects: an acquisition sieve effect (exclusion of certain variants from establishing infection due to the ability of the vaccine to block certain viruses from establishing infection); or post-infection sieve effects (occurs when vaccine-induced anamnestic responses influence the evolutionary outgrowth of specific HIV-1 variants) [1]. Sieve analysis has been successfully applied to two large vaccine trials, RV144 [2,3] and the Step study [4] (Merck 023/HVTN 502 trial). While the RV144 vaccine trial showed modest protection [5], Step neither prevented infection nor reduced viral load [6], demonstrating that even in the absence of vaccine efficacy, there was vaccine-induced viral selection in breakthrough infections [4].

The Step Study was conducted in subtype-B epidemic regions and evaluated the Merck Adenovirus-5 (MrkAd5) Gag/Pol/Nef subtype-B vaccine, designed to elicit cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) responses [6,7]. The Phambili study (HVTN 503), a Phase 2b placebo-controlled preventive vaccine efficacy trial, was run in parallel with the Step Study and evaluated the same vaccine in a predominantly subtype-C epidemic region [8]. The Phambili Study was halted prematurely after an interim analysis of the Step study showed lack of efficacy [6]. Similar to Step, the Phambili study found that the vaccine neither prevented HIV-1 infection nor reduced viral load set-point post-infection, and showed trends of a higher HIV-1 infection rate in the vaccine group [4,8].

Sieve analysis of the Step study identified a greater divergence of predicted epitope sequences from the vaccine immunogen sequence in vaccine compared to placebo breakthrough infections [4]. One signature site was identified, Gag 84, which differentiated vaccine from placebo sequences and remained significant after stringent adjustment for multiple comparisons [4]. Here we report on a sieve analysis of 43 breakthrough-infected study participants from the Phambili study. We identified evidence of sieve effects however the effects observed were statistically weaker than those observed in the Step Study, and we evaluated how sample size, differing distribution of HLA alleles in the study populations, and mismatch between vaccine and infecting subtype, may have affected these findings.

2. Materials and methods

See supplementary materials for further details on methods.

2.1. Ethics statement

This study was approved by the University of Cape Town research ethics committee. The protocol was approved by all study sites and all participants gave informed consent after the nature and possible consequences of the studies had been fully explained [8].

2.2. Phambili cohort

Individuals were part of the Phambili double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled Phase 2b study. The MrkAd5 HIV-1 Gag/Pol/Nef (Merck and Co., Inc.) vaccine insert was composed of the three subtype B sequences CAM-1/IIIB/JRFL.

Four digit high-resolution typing of class I HLA-A, -B, and -C loci was performed by DNA sequence-based typing (SBT) of exons 2 and 3 [9] using the dbMHC SBT interpretation interface (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gv/mhc/).

2.3. Near full-length genome sequencing

Near full-length HIV-1 genome sequences were generated using the limiting dilution/single genome amplification approach, followed by direct sequencing of PCR products [4,10] (GenBank accession numbers: KT183051–KT183341). The Step Study sequences were the same as those analyzed previously [4]. Data are also available online as an interactive visualization (http://sieve.fredhutch.org/viz).

2.4. Sequence analysis

Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic trees were generated using the GTR model of nucleotide substitution employed by PhyML [11]. For methods requiring one representative amino acid sequence per participant, the majority founder consensus sequence was used. Where there were multiple founder strains, the consensus sequence was calculated only from the founder that had the most observed sequences. Definition of complexity of transmitted variants was based on mathematical modeling combined with the phylogenetic approach [12].

Mean 9-mer epitope-coverage of the MrkAd5 vaccine was determined by a sliding 9-mer window using Epicover (www.hiv.lanl.gov) [13]. Potential coverage of the vaccine was calculated as the mean fraction of all 9-mer peptides in the MrkAd5 vaccine sequence that matched epitope-length peptides in the subtype-B or subtype-C sequence sets.

2.5. Testing for sieve effects

All of the statistical tests for sieve effects use two-sided p-values, to consider the possibility of differences between the treatment arms in either direction. P-values were unadjusted for multiple comparisons except where noted.

2.6. Global (protein) sieve analysis

Whole-protein pairwise distances of HIV-1 sequences from vaccine insert sequence were determined using (1) Hamming (mismatch) distance, (2) physicochemical similarity (‘‘global PCP”), calculated using z-scales that quantify structure-activity relationships between different amino acids [13–15,19]; and (3) the quasi-earth mover's distance (QEMD) [2,16]. Phylogenetic distance was calculated as the total branch length [2].

2.7. T Cell sieve methods

T cell based sieve methods were used in which HLA binding predictors, or annotated HIV epitopes from LANL, were to used compare the sequences of breakthrough viruses to the vaccine insert including: (1) Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) epitope mismatch, (2) percent epitope mismatch, (3) HLA binding escape, (4) insertion/deletion (indel) binding escape, (5) HLA binding + indel escape, and (6) relative HLA binding escape.

2.8. Local sieve analysis methods

Distribution of amino acids at individual positions or within contiguous 9-mers were compared. To conserve statistical power, we excluded sites with low variability (treatment-blinded). After filtering, 107 sites in Gag (19%), 65 sites in Nef (29%), and 109 sites in Pol (10%) remained for analysis. Three methods compared the amino acid distribution of breakthrough infections at individual sites against the residue found in the vaccine insert: (1) “Expected Gilbert, Wu, Jobes” method (EGWJ) which uses all sequences from all participants; (2) “Gilbert, Wu, Jobes” method (GWJ) [17] uses only the majority founder consensus sequence from each participant; and (3) the “Model-Based Sieve” (MBS) approach [18] that uses a Bayesian model comparison that is more sensitive to detect treatment effects that alter the distribution among non-vaccine-matched amino acids. One method, the “local PCP”, compared the distribution of the physicochemical properties of the site-specific residues between the treatment groups, not making use of the vaccine insert (or any other) reference sequence.

Contiguous 9-mer regions, rather than single amino acid sites, were also evaluated in order to be more sensitive to potential vaccine-induced T cell epitopes. These included: (1) HLA binding escape; (2) indel binding escape; (3) relative HLA binding escape; (4) K-mer scan; and (5) local PCP.

3. Results

To analyze sieve effects exerted by the MrkAd5 subtype B vaccine tested in South Africa, an HIV-1 subtype C epidemic region, we used a similar approach as the Step Study sieve analysis [4].

3.1. Sieve analysis sequence dataset

At the time the study was initiated, 62 individuals had acquired HIV-1 [8] of whom 43 (20 placebo and 23 vaccine) were selected for sequencing (Table 1). Samples from the first HIV-1-positive visit were sequenced and participants were included based on time from diagnosis, number of vaccinations, and time from vaccination (Table 1). 277 near-full-length HIV sequences were generated, with the mean number for each participant in the placebo and vaccine groups of 6.89 (range 5–12) and 6.00 (range 2–12), respectively (Fig. 1). Forty individuals were infected with subtype C, while one subtype A1 and one C/A recombinant infections were identified in vaccine recipients, and one C/B recombinant infection was identified in a placebo recipient. Both recombinant viruses were subtype C in the gene regions matched to the vaccine, with evidence of non-C sequences predominantly occurring in Env. Unless mentioned specifically, we included the sequences from all 43 participants in these analyses.

Table 1.

Characterization of Phambili HIV-1 infected study participants and infecting viruses.

| Gender |

Subtype/recombinant | Complexity of virusa |

Tierb |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Homogen. | Heterogen. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 7 | ||

| Vaccine | 8 | 15 | 21 C, 1 A1, 1 CA | 17 | 4 | 3 | 12 | 6 | 2 | 0 |

| Placebo | 7 | 13 | 19 C, 1 CB | 16 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

Excluded two participants with fewer than five sequences.

Not all infected participants were selected for sequencing. Participants were selected by order of tier criteria 1, 2, 3, 4, 7. Tier 1: ≥2 vaccinations and HIV PCR positive/antibody negative; Tier 2: ≤60 days since infection, and either ≥2 vaccinations and ≤550 days since last vaccination, or 1 vaccination and ≤275 since last vaccination; Tier 3: ≥2 vaccinations, ≤100 days since infection and ≤550 days since last vaccination; Tier 4:1 vaccination, ≤100 days since infection and ≤365 days since last vaccination; Tier 7: >2 immunizations; days since infection >60; days since last vaccination >550.

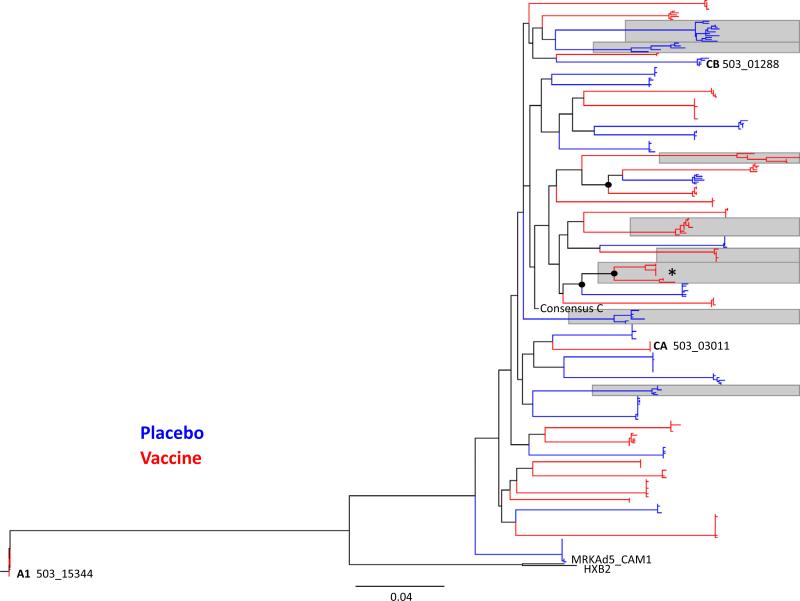

Fig. 1.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of 277 gag nucleotide sequences from 43 participants. Tree comprises sequences from 43 individuals: 40 were infected with subtype-C viruses, and 3 with non-subtype-C viruses (C/A and C/B recombinants and a subtype A1). For reference, subtype-B strains CAM_01 (the gag gene included in the MRK-Ad5 vaccine) and HXB2 were included. Terminal branches in blue indicate placebo-recipient sequences and those in red vaccine-recipient sequences. Gray boxes denote individuals with heterogeneous infections. Internal branches with node support >80% are indicated with black circles.

3.2. Founder analysis

To determine whether the vaccine affected the transmission bottleneck, we analyzed genetic complexity of viruses from 41 individuals with five or more sequences. Thirty-three participants harbored homogenous viral populations, and 8 participants were infected with heterogeneous viral populations (Table 1, Fig. 1). We found no discernible difference in the ratio of homogeneous to heterogeneous viral populations establishing infection across treatment arms, with 17/21 (81%) homogeneous infections in the vaccine arm compared to 16/20 (80%) in the placebo arm. One participants’ envelope sequences clustered separately on phylogenetic trees, suggesting infection with two distinct viral strains (Fig. S1).

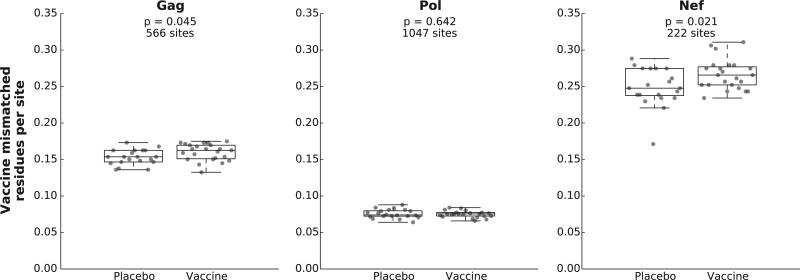

3.3. Evidence of global sieve effects in Gag and Nef proteins

Computing the protein mismatch distance of each breakthrough infecting sequence to the vaccine insert across treatment groups using Hamming distance analysis, we found statistically significant evidence that viruses in the vaccine arm were more distant from the vaccine insert for both Gag and Nef (Fig. 2; p = 0.045 and 0.021 respectively). Using methods that compare the distribution of distances between vaccine and placebo recipients directly, and do not make use of the vaccine insert sequence, we also found significant differences for Gag using the Global PCP method (p = 0.037), and for Nef using both Global PCP and QEMD methods (0.032 and 0.030 respectively). We found no evidence for treatment-associated differences using phylogenetic distance methods (Table S2).

Fig. 2.

Hamming distances between vaccine insert sequences and breakthrough virus sequences. Distances between the vaccine immunogen and each breakthrough virus was computed with distance for each participant measured as the fraction of amino acid residues in their majority founder consensus sequence that mismatched the aligned vaccine insert sequence. Distance was computed separately for each participant (gray circles) and for each protein encoded by the vaccine: Gag (Panel A), Pol (Panel B), Nef (Panel C). Boxes indicate the median and inter-quartile range (IQR) of the distances for each treatment group with whiskers indicating the range of the distances within 1.5 times the IQR. One Pol sequence was removed as it was incomplete. Treatment groups were compared using a pooled-variance t-statistic. Statistical significance was determined by calculating two-sided p-values using a permutation test on the treatment labels.

3.4. No evidence of CD8+ T cell-specific vaccine-induced pressure

Applying the same sieve analysis methods used for the Step Study, as well as novel methods that consider predicted HLA-binding escape via amino-acid substitutions and insertions/deletions [3], we identified no evidence of CD8-mediated sieve effects at a whole protein level, nor at the individual epitope level (Table S3). We also used the “k-mer scan” and the “local PCP” methods to compare 9-mers between vaccine and breakthrough sequences and found no statistically significant evidence of a sieve effect at any 9-mer after adjusting the p-values to control the false discovery rate at 20% (Table S4).

3.5. Local sieve analyses identified putative sites of vaccine-induced pressure

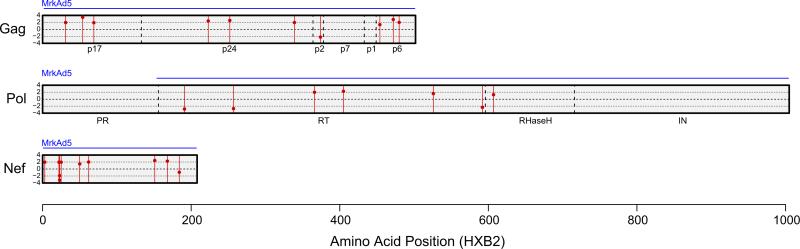

We applied similar statistical approaches to examine differences in individual amino acid sites or short k-mers as those previously reported in both the Step [4] and RV144 trials [2,20]. We employed four site-specific local sieve analysis methods. All sites with an unadjusted two-sided p-value <0.05 by any of the four site-specific methods were considered a putative “signature site”. False discovery rate q-values were computed for each protein separately.

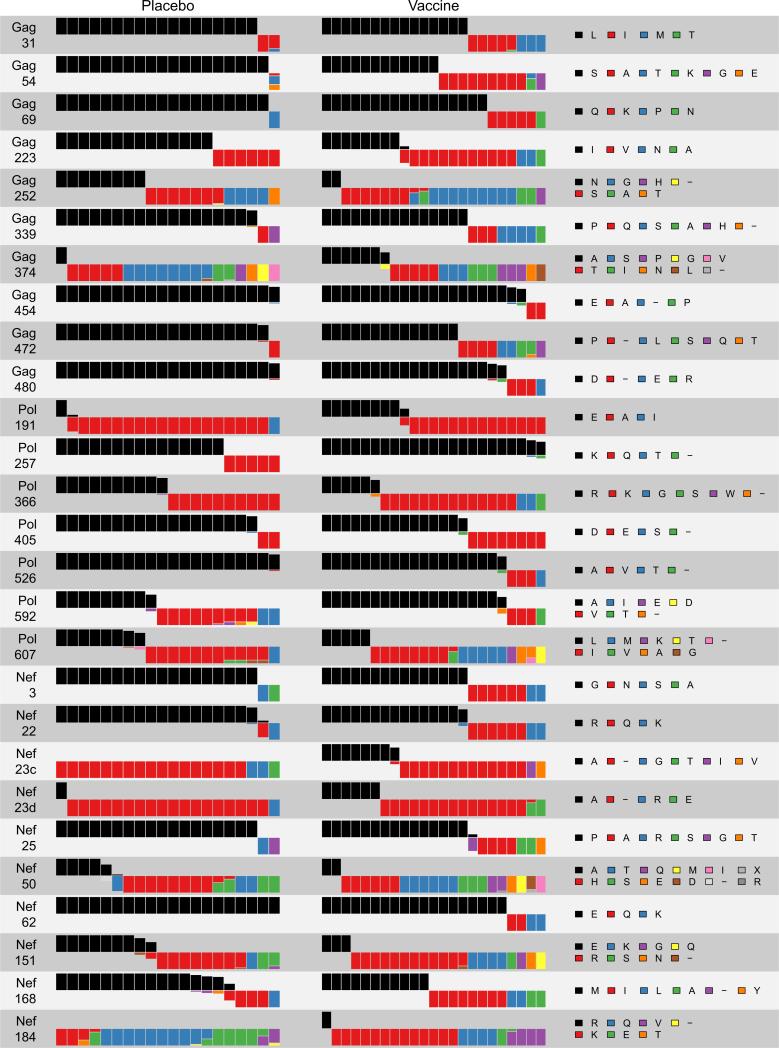

Twenty-seven putative signature sites were identified (Fig. 3a, b and Table 2). Twenty (74%) were classified as typical “vMatch” sieve effects as there was a larger fraction of vaccine-matched amino acids among placebo recipients compared to vaccine recipients, consistent with the hypothesis that there is selection against vaccine-matched viruses by vaccine-induced immune responses. Seven (26%) were classified as atypical “vMismatch” sieve effects, as there was a larger fraction of vaccine-matched amino acids among vaccine recipients compared to placebo recipients. In sequence data without a true sieve effect, we would falsely identify about 5% of all sites as signature sites (using p < 0.05) and we would expect that the frequency of vMatch and vMismatch effects would be equal. Under this assumption of equal occurrence and using a two-tailed exact binomial test, the probability of observing such a high proportion of vMatch signature sites as we did here (74%) is 0.019. The corresponding probabilities for the individual proteins Gag, Pol and Nef are 0.021, 1.0, and 0.34, respectively. Under a model that most true vaccine signature site sieve effects are expected to be of the vMatch type, this result strengthens the evidence against the null hypothesis of no sieve effects and favors the finding of sieve effects at some of the amino acid sites. However, due in part to the large number of sites that were tested and the relatively small number of participants that were sequenced (n = 43), none of these 27 putative signature sites were found to be statistically significant after the p-values were adjusted to control the false-discovery rate at 20%.

Fig. 3.

Signature site location and distribution. (a) Locations of signature sites found in the vaccine insert protein. All sites with evidence for a different amino acid distribution in vaccine versus placebo sequences relative to the vaccine immunogen reference residue (unadjusted p < 0.05) by any of the site-scanning methods DVE, GWJ, MBS, or local PCP are shown. The blue horizontal lines above the protein regions indicate the regions included in the vaccine immunogen sequences. Signature sites are indicated by red vertical lines, with a red point that is placed on the line as an indicator of the magnitude of the site's test statistic using the GWJ method, which is a t-statistic comparing substitution weights across treatment groups. The black dashed horizontal lines in the middle of the gene and protein regions indicate the zero-point for the test statistic, so the farther away the point is from the center line, the more significant it was observed to be with this method. Points above the dashed line indicate that a site was found to have a “vMatch” sieve effect (greater frequency of vaccine-mismatched residues in vaccine than placebo viruses), while points below the dashed line indicate “vMismatch” signature sites (greater frequency of vaccine-mismatched residues in placebo than vaccine viruses). (b) Signature site amino acid distributions. All sites with evidence for a different amino acid distribution in vaccine versus placebo sequences relative to a reference residue (unadjusted p < 0.05) by any of the site-scanning methods (DVE, GWJ, MBS or local PCP) in the vaccine immunogen are shown. For each identified signature site, the distributions of amino acids from the vaccine and placebo recipients’ sequences are shown relative to the insert's amino acid. Each participant is represented by a bar of equal height. Within a bar, colors depict the fraction of the participant's sequences with that amino acid residue (or insertion or deletion, indicated by a “–”). The vaccine sequence amino acid residue, in black, is shown above the midline while vaccine-mismatched residues are shown below the midline. The widths of the bars are scaled so that the total width of the vaccine-recipient part of the plot is the same as for the placebo-recipient part.

Table 2.

Putative amino acid signature sites identified using site-specific sieve methods. All sites at which the null hypothesis of no sieve effect was rejected by at least one of the four local sieve analysis methods (EGWJ, GWJ, MBS and local PCP). Unadjusted p-values are listed in the columns for each method, with the results bolded if they were significant (p < 0.05).

| Protein | AA Site HXB2 No. | Statusa | GWJ | EGWJ | MBS | Local PCPb | Related results from 9-mer-based analysisc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gag | Gag 31 | vMatch | 0.065 | 0.037 | 0.073 | k-mer scan: 23 | |

| Gag 54 | vMatch | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.010 (hydrophobic) | k-mer scan and local PCP (z4): 46-53 | |

| 0.025 (polar) | |||||||

| 0.022 (z1) | |||||||

| 0.012 (z4) | |||||||

| Gag 69 | vMatch | 0.127 | 0.048 | 0.053 | k-mer scan: 65 | ||

| Gag 223 | vMatch | 0.022 | 0.024 | 0.021 | k-mer scan: 216-223 | ||

| Gag 252 | vMatch | 0.007 | 0.010 | 0.009 | k-mer scan and local PCP (polar): 244-248 | ||

| Gag 339 | vMatch | 0.075 | 0.037 | 0.097 | |||

| Gag 374 | vMismatch | 0.051 | 0.340 | 0.034 | Local PCP (z5): site 368. Binding escape: 369 | ||

| Gag 454 | vMatch | 0.584 | 0.039 | 0.558 | k-mer scan: 449-450 | ||

| Gag 472 | vMatch | 0.018 | 0.004 | 0.032 | 0.034 (z4) | Local PCP (polar, small, proline, z1, z2): sites 468-472. k-mer scan: 470 | |

| Gag 480 | vMatch | 0.147 | 0.028 | 0.141 | k-mer scan: 475, 478, 480 | ||

| Pol | Pol 191 | vMismatch | 0.010 | 0.086 | 0.011 | 0.022 (z1) | k-mer scan: 183-191. Local PCP (charged, z1): 183-186 |

| 0.038 (z2) | |||||||

| 0.039 (z4) | |||||||

| Pol 257 | vMismatch | 0.030 | 0.031 | 0.033 | |||

| Pol 366 | vMatch | 0.034 | 0.054 | 0.034 | Local PCP (z1, z2): 359-362 | ||

| Pol 405 | vMatch | 0.058 | 0.035 | 0.052 | |||

| Pol 526 | vMatch | 0.260 | 0.038 | 0.143 | |||

| Pol 592 | vMismatch | 0.024 | 0.034 | 0.232 | 0.016 (z1) | k-mer scan: 591-592. Local PCP (aliphatic, z1, z3, z4, z5): 584-590 | |

| 0.049 (z3) | |||||||

| Pol 607 | vMatch | 0.107 | 0.200 | 0.041 | 0.031 (z1) | Local PCP (z3): 605 | |

| Nef | Nef 3 | vMatch | 0.031 | 0.030 | 0.034 | 0.041 (z1) | k-mer scan and local PCP (z2): 3 |

| Nef 22 | vMatch | 0.064 | 0.028 | 0.118 | k-mer scan: 22-25. Binding scan: 23d. Local PCP (charged): 16-17 | ||

| Nef 23c | vMismatch | 0.003 | 0.066 | 0.004 | 0.003 (z5) | ||

| Nef 23d | vMismatch | 0.042 | 0.380 | 0.129 | |||

| Nef 25 | vMatch | 0.116 | 0.047 | 0.034 | |||

| Nef 50 | vMatch | 0.260 | 0.091 | 0.037 | |||

| Nef 62 | vMatch | 0.180 | 0.031 | 0.156 | |||

| Nef 151 | vMatch | 0.048 | 0.023 | 0.085 | k-mer scan: 145-149. Local PCP (z4): 147 | ||

| Nef 168 | vMatch | 0.031 | 0.040 | 0.067 | k-mer scan: 164. Local PCP (z3, z5): 161-164 | ||

| Nef 184 | vMismatch | 1.000 | 0.680 | 0.838 | 0.009 (hydrophobic) | Local PCP (hydrophobic, positive, z1, z4): 176-184 | |

| 0.012 (positive) | |||||||

| 0.005 (z3) | |||||||

| 0.002 (z4) |

Sites are classified as vMatch if there is a larger fraction of vaccine-matched amino acids among placebo recipients, and as vMismatch if there is a larger fraction of vaccine-matched amino acids among vaccine recipients compared to placebo recipients.

Local PCP p-values are Bonferroni-corrected across the properties for each scale (10 properties for Taylor's categorical properties, 5 properties for Wold's z-scales), and are only listed if significant, showing the property or scale that was significant in parentheses.

Annotation in the final column compares these sites with the results of the 9-mer-based analysis, showing the starting position of any 9-mer that overlaps the individual site of interest.

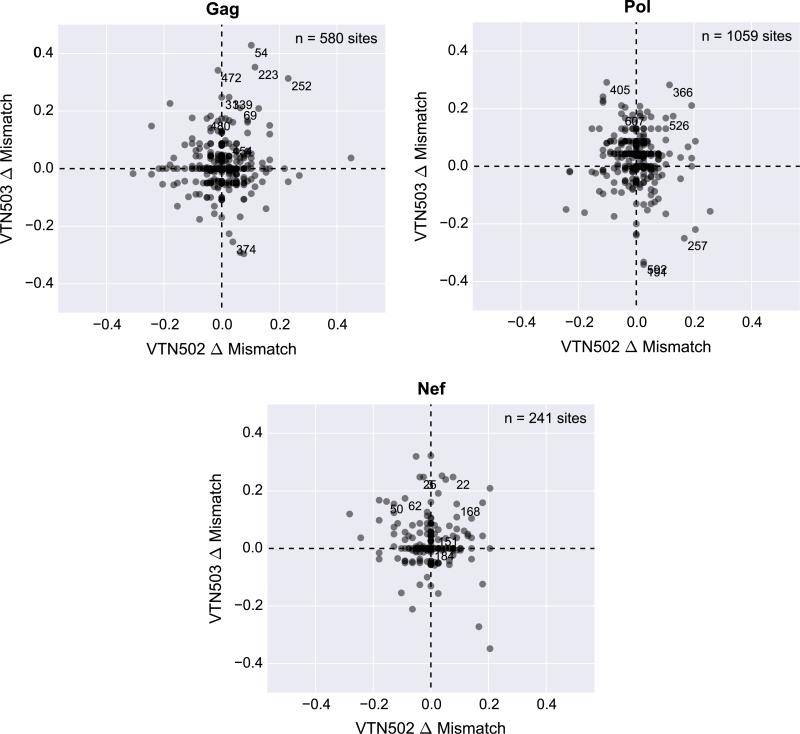

To determine if there were similarities between the signature sites identified in Step and Phambili we plotted the treatment difference in the percent of vaccine-mismatched residues (vaccine minus placebo) for all sites in Gag, Pol and Nef for the two studies and annotated the Phambili signature sites (Figs. 4 and S3). There was no evidence that there was an overlap of signature sites between the two studies.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of putative site-specific sieve effects observed in the Step and Phambili Studies. The magnitude of a site-specific sieve effect can be computed as the treatment difference in the percent of vaccine-mismatched breakthrough viruses at each site (vaccine minus placebo). A positive and larger difference indicated a “vMatch” sieve effect (greater frequency of vaccine-mismatched residues in vaccine than placebo viruses). Scatter plots compare the difference computed at each site (gray dot) for the Step (x-axis) and Phambili (y-axis) trials and for each protein encoded by the vaccine insert: Gag (A), Pol (B) and Nef (C). The differences are comparable despite the difference in the number of infections that were included in the sieve analysis for each trial (Step: n = 65; Phambili: n = 43). If a site-specific sieve effect from Step was replicated it would appear in the upper right or lower left quadrant. Sites in the upper left and lower right reflect possible sieve effects in one study, but not the other. The symmetric cloud of sites towards the origin is expected since the magnitude of the sieve effect at most sites reflects the lack of a sieve effect and noise in the data. Only the sieve effect at Gag 84 in the Step Study reached statistical significance after adjustment for multiple comparisons. Signature sites in the Phambili Study are annotated with the site numbers.

3.6. Factors that may contribute to lower signal in Phambili compared to Step

The signal identified in Phambili was statistically weaker than identified in Step, and we performed a sensitivity analysis to investigate whether Phambili's smaller sample size (43 vs. 65 Step) rendered it underpowered to detect a sieve signal of similar magnitude. Using Step sequences, for 1000 iterations, we simulated the Phambili sample-size conditions by randomly selecting 23 of the infected vaccine recipients and 20 of the infected placebo recipients, and for each iteration we performed the site-specific sieve analysis on all three insert proteins using the GWJ and MBS methods. Gag 84 survived multiplicity adjustment (q < 0.2 and Holm-Bonferroni adjusted p < 0.05) and was highly significant (p < 0.001) for both methods in every iteration and was the only site in all three insert proteins to survive multiplicity adjustment.

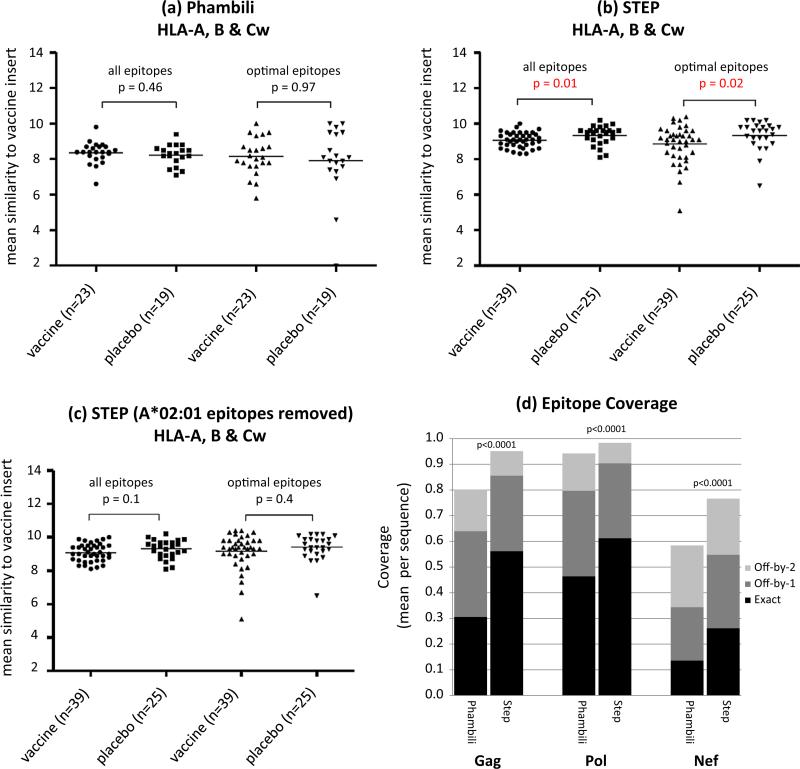

We then investigated the influence of host HLA alleles and found differences in the distributions of the participants’ HLA alleles (Fig. S2), including a large difference in the frequency of HLA A*02. While in Step there was evidence of a sieve effect when CTL epitopes were predicted on the vaccine insert and compared to HLA relevant regions on the viral proteins, no such effect was found for Phambili (Fig. 5a–c). However, this signal lost significance when A*02:01 epitopes were removed, suggesting that the lower frequency of A*02 alleles among Phambili participants would by itself be sufficient to lead to different vaccine-induced epitopes and lower CD8 T cell pressure.

Fig. 5.

T cell-mediated sieve analyses on (a) Phambili (n = 42, subtype A virus excluded) and (b) Step (n = 64) Gag sequences. (c) Gag Step sieve analysis, excluding HLA-A*02:01 restricted epitopes. Mean (per participant) epitope similarity to vaccine insert in Gag is illustrated. Epitopes were predicted on the vaccine insert by accepting a peptide region as an epitope if it had at least 70% similarity to an epitope listed in the Los Alamos HIV database (http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/immunology/tables/tables.html) for all epitopes and optimal (A-list) CTL epitopes. The similarity scores between the predicted epitopes on the vaccine insert and corresponding sites on the participant sequences were calculated using the HIV-between amino acid similarity scoring matrix. Matches were restricted to epitopes that are presented by each individual's specific HLA genotypes. (d) Mean 9-mer MrkAd5 vaccine epitope coverage of sequences from the Phambili trial (n = 43) (40 subtype C, 1 A, 1 CB, and 1 CA recombinant) and subtype-B sequences originating from the Step Study (n = 65). Coverage was estimated by sliding a 9-mer window position-by-position through the proteome of Gag, Pol and Nef. Potential coverage of the vaccine was calculated as the mean fraction of all 9-mer peptides in the MrkAd5 vaccine sequence that was shared with the participant in the vaccine and placebo group sequence, without regard to HLA. Match tolerances analyzed were an exact match, one amino acid mismatch, or two amino acid mismatches (http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/sequence/MOSAIC/epicover.html).

Lately, we investigated the potential impact of genetic distance between the vaccine insert and circulating viruses based on placebo recipient sequences. The average mismatch between the vaccine and breakthrough viruses in Phambili of 15.3%, 7.6% and 24.9% for Gag, Pol and Nef, respectively, was considerably higher than what was observed for Step (6.7%, 5.4% and 19.1%). As peptides containing more than three mismatches typically lack cross-reactive activity [21], we then compared the 9-mer coverage of the MrkAd5 vaccine by computing the percentage of 9-mers that were exact matches to the vaccine inserts. While the coverage of the vaccine against the Phambili subtype-C viruses was 31%, 46% and 14% for Gag, Pol and Nef, respectively, the same analysis repeated against subtype B Step sequences gave coverage of 56%, 61% and 26%, respectively (Fig. 5d).

4. Discussion

We conducted a sequence analysis of breakthrough infections in the Phambili HIV-1 vaccine trial to detect and characterize vaccine-induced immune pressure. We found evidence for global sieve effects in Gag and Nef which were robust to three different methods for computing a genetic distance, suggesting that the result does not depend on a specific definition of sequence similarity. Evidence of vaccine pressure in Gag has now been found across three different HIV-1 efficacy studies (Step, Phambili and RV144), although by different methods.

We identified 27 putative amino acid signature sites that differed between vaccine and placebo recipients, many of which were located in positions associated with CD8 T cell pressure in natural infection (Table S5). None of these remained statistically signifi-cant following multiplicity adjustment, which is different from the Step study which identified a robust signature at Gag 84, a site encompassed by several documented T cell epitopes [4]. Differences in host genetics may have reduced our ability to detect vaccine effects in Phambili. The high frequency of the A*02 alleles in Step, for example, was a strong contributor of the ability to detect the Gag 84 signature site, and we found that differences in the frequency of this allele would by itself be sufficient to lead to different vaccine-induced epitopes and lower CD8 T cell pressure.

Incomplete vaccination or the high genetic distance between the vaccine and the breakthrough infections may have also contributed to weaker signal seen in Phambili. While 38 of the 65 (58%) Step Study infected participants analyzed completed their three-immunization vaccination schedules, none of the participants in the Phambili sieve analysis received a complete vaccination course. The frequency of responses, however, was similar in both trials, with T cell responses in more than three-quarters of participants [4,8,7]. A subtype effect however was observed in Phambili, where more participants developed an interferon-γ-secreting T cell response to clade B peptides (89%) than to clade C peptides (77%), and the overall magnitude of response to the subtype B vaccine-matched panel was significantly higher than to the subtype C potential T cell epitope panel (p < 0.0001) [8]. Given these results, it is reasonable to expect that participants in this study would exhibit a less-effective vaccine response than would participants in Step. This further suggests the importance of matching the vaccine immunogens to the circulating HIV-1s in the geographic region(s) of an efficacy trial.

Recent advances in the sieve analysis field have provided a variety of methods, for detecting specific types of sieve effects [2]. The global and local sieve effects detected in Step, RV144 and Phambili were identified using different methods, which were not always in agreement with one another. This suggests that additional research is required to study the differences between the methods. We suggest that methods need to be compared predominantly on point estimates of vaccine efficacy (VE) (comparing the estimated VE against matched HIV strains to the estimated VE against mismatched HIV strains), rather than by comparing p-values for sieve effects. This is due to the fact that it is easy for one method to give a borderline significant sieve effect p-value (or q-value), and for another to give a borderline insignificant sieve effect p-value (or q-value), but show no meaningful difference in the results on the interpretable estimated VE scale.

In conclusion, we present evidence of global sieve effects in Gag and Nef, and local sieve effects at amino acid sites. However, the effects are only moderate in nature, and while they suggest that the MRKAd5 HIV-1 Gag/Pol/Nef vaccine induced immune pressure on breakthrough infections in the Phambili trial, their status as false discoveries cannot be ruled out. We propose that the mismatch between the vaccine and infecting subtype, together with differences in HLA distribution reduced our ability to detect vaccine sieve effects in the Phambili study. Smaller sample size and lack of complete vaccination schedule may also have contributed. Sieve analyses and immune measures are our most important tools for understanding the immune response to vaccination and this study illustrates the importance that host genetics and vaccine insert clade mismatch can have on vaccine effects.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge and appreciate the efforts and the sacrifices made by the volunteers in the Phambili Study; the HVTN Laboratory Program, SCHARP, and Core staff who contributed to the study implementation and analysis; the Merck functional teams: the Clinical Research Specialist Organization, Worldwide Clinical Data Management Operation, Clinical Research Operations, and the Clinical Assay and Sample Receiving Operations.

Funding statement

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers R37AI054165, UM1AI068635, and UM1AI068618. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Conflict of interest statement

This work was supported in part by a cooperative agreement (W81XWH-07-2-0067) between the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc., and the U.S. Department of Defence (DoD). The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the positions of the U.S. Army or DoD. MR is an employee of the Henry M. Jackson Foundation.

Part of this work was presented at the AIDS Vaccine Meeting 2011, 12–15 September, Bangkok, Thailand.

Footnotes

Author contribution

Wrote the manuscript (TH, MGL, MR, CAM, CR, AFG, PTE, PBG, CW); designed and supervised the laboratory experiments (CW, JIM); designed the sequence analysis (TH, MGL, MR, CAM, AdC, CR, PTE, PBG, CW); analyzed the data (TH, MGL, MR, CAM, AdC, AFG, PTE, HA, CR, NN, PBG, CW); performed laboratory experiments (MGL, CR, JM, RT, FT, BBL, DG); conducted the HVTN 503 trial, provided material, and oversaw laboratories (NF, JH, LC, JK, GG, MJM).

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.09.054.

References

- 1.Edlefsen PT, Gilbert PB, Rolland M. Sieve analysis in HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trials. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2013;8:432–6. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e328362db2b. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/COH.0b013e328362db2b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edlefsen PT, Rolland M, Hertz T, Tovanabutra S, Gartland AJ, DeCamp AC, et al. Comprehensive sieve analysis of breakthrough HIV-1 sequences in the RV144 vaccine efficacy trial. PLOS Comput Biol. 2015;11:e1003973. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003973. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gartland AJ, Li S, McNevin J, Tomaras GD, Gottardo R, Janes H, et al. Analysis of HLA A*02 association with vaccine efficacy in the RV144 HIV-1 vaccine trial. J Virol. 2014;88:8242–55. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01164-14. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01164-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rolland M, Tovanabutra S, DeCamp AC, Frahm N, Gilbert PB, Sanders-Buell E, et al. Genetic impact of vaccination on breakthrough HIV-1 sequences from the STEP trial. Nat Med. 2011;17:366–71. doi: 10.1038/nm.2316. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nm.2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rerks-Ngarm S, Pitisuttithum P, Nitayaphan S, Kaewkungwal J, Chiu J, Paris R, et al. Vaccination with ALVAC and AIDSVAX to prevent HIV-1 infection in Thailand. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2209–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908492. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0908492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchbinder SP, Mehrotra DV, Duerr A, Fitzgerald DW, Mogg R, Li D, et al. Efficacy assessment of a cell-mediated immunity HIV-1 vaccine (the Step Study): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, test-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2008;372:1881–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61591-3. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61591-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McElrath MJ, De Rosa SC, Moodie Z, Dubey S, Kierstead L, Janes H, et al. HIV-1 vaccine-induced immunity in the test-of-concept Step Study: a case–cohort analysis. Lancet. 2008;372:1894–905. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61592-5. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61592-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gray GE, Allen M, Moodie Z, Churchyard G, Bekker L-G, Nchabeleng M, et al. Safety and efficacy of the HVTN 503/Phambili study of a clade-B-based HIV-1 vaccine in South Africa: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled test-of-concept phase 2b study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:507–15. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70098-6. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70098-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ovsyannikova IG, Jacobson RM, Vierkant RA, O'Byrne MM, Poland GA. Replication of rubella vaccine population genetic studies: validation of HLA genotype and humoral response associations. Vaccine. 2009;27:6926–31. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.08.109. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.08.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abrahams M-R, Anderson JA, Giorgi EE, Seoighe C, Mlisana K, Ping L-H, et al. Quantitating the multiplicity of infection with human immunodeficiency virus Type 1 subtype C reveals a non-poisson distribution of transmitted variants. J Virol. 2009;83:3556–67. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02132-08. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.02132-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deng W, Maust B, Nickle D, Learn G, Liu Y, Heath L, et al. DIVEIN: a web server to analyze phylogenies, sequence divergence, diversity, and informative sites. Biotechniques. 2010;48:405–8. doi: 10.2144/000113370. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2144/000113370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keele BF, Giorgi EE, Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Decker JM, Pham KT, Salazar MG, et al. Identification and characterization of transmitted and early founder virus envelopes in primary HIV-1 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105:7552–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802203105. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0802203105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thurmond J, Yoon H, Kuiken C, Yusim K, Perkins S, Theiler J, et al. Web-based design and evaluation of T-cell vaccine candidates. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:1639–40. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn251. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btn251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hellberg S, Sjoestroem M, Skagerberg B, Wold S. Peptide quantitative structure-activity relationships, a multivariate approach. J Med Chem. 1987;30:1126–35. doi: 10.1021/jm00390a003. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jm00390a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandberg M, Eriksson L, Jonsson J, Sjöström M, Wold S. New chemical descriptors relevant for the design of biologically active peptides. A multivariate characterization of 87 amino acids. J Med Chem. 1998;41:2481–91. doi: 10.1021/jm9700575. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/jm9700575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rubner Y, Tomasi C, Guibas LJ. The earth mover's distance as a metric for image retrieval. Int J Comput Vis. 2000;40:2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilbert PB, Wu C, Jobes DV. Genome scanning tests for comparing amino acid sequences between groups. Biometrics. 2008;64(1):198–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2007.00845.x. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0420.2007.00845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edlefsen PT. Evaluating the dependence of a non-leaky intervention's partial efficacy on a categorical mark. 2014 arXiv:1206:6701v2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0420.2005.00454.x.

- 19.Taylor WR. The classification of amino acid conservation. J Theor Biol. 1986;119:205–18. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(86)80075-3. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5193(86)80075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rolland M, Edlefsen PT, Larsen BB, Tovanabutra S, Sanders-Buell E, Hertz T, et al. Increased HIV-1 vaccine efficacy against viruses with genetic signatures in Env V2. Nature. 2012;490:417–20. doi: 10.1038/nature11519. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature11519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rolland M, Frahm N, Nickle DC, Jojic N, Deng W, Allen TM, et al. Increased breadth and depth of cytotoxic T lymphocytes responses against HIV-1-B Nef by inclusion of epitope variant sequences. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e17969. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017969. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0017969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.