Abstract

Glycoside phosphorylases catalyze the phosphorolysis of oligosaccharides into sugar phosphates. Recently, we found a novel phosphorylase acting on β-1,2-glucooligosaccharides with degrees of polymerization of 3 or more (1,2-β-oligoglucan phosphorylase, SOGP) in glycoside hydrolase family (GH) 94. Here, we characterized SOGP from Lachnoclostridium phytofermentans (LpSOGP) and determined its crystal structure. LpSOGP is a monomeric enzyme that contains a unique β-sandwich domain (Ndom1) at its N-terminus. Unlike the dimeric GH94 enzymes possessing catalytic pockets at their dimer interface, LpSOGP has a catalytic pocket between Ndom1 and the catalytic domain. In the complex structure of LpSOGP with sophorose, sophorose binds at subsites +1 to +2. Notably, the Glc moiety at subsite +1 is flipped compared with the corresponding ligands in other GH94 enzymes. This inversion suggests the great distortion of the glycosidic bond between subsites −1 and +1, which is likely unfavorable for substrate binding. Compensation for this disadvantage at subsite +2 can be accounted for by the small distortion of the glycosidic bond in the sophorose molecule. Therefore, the binding mode at subsites +1 and +2 defines the substrate specificity of LpSOGP, which provides mechanistic insights into the substrate specificity of a phosphorylase acting on β-1,2-glucooligosaccharides.

Glycoside phosphorylases catalyze the phosphorolysis of oligosaccharides into sugar phosphates in the metabolism of specific sugars1,2. Phosphorylation of sugars without an energy source such as ATP is advantageous for saving energy physiologically3. In the application area, the reversibility of reactions and strict regioselectivity of glycoside phosphorylases are of great use for oligosaccharide synthesis4. The combination of two glycoside phosphorylases sharing a common donor substrate enhances the use of this type of enzymes, since the use of an expensive sugar 1-phosphate as a starting material can be avoided5,6. Despite several recent findings regarding new glycoside phosphorylases7, the repertoire of glycoside phosphorylases is still much smaller than that of glycoside hydrolases. In addition, the distribution of glycoside phosphorylases is limited to glycoside hydrolase (GH13, GH65, GH94, GH112, and GH130) and glycosyltransferase (GT4 and GT35) families7,8,9 (In the GH3 family, only one glycoside phosphorylase has been reported in subgroup NagZ10). Determination of the structural basis for glycoside phosphorylases is important for protein engineering to expand the variety of reactions along with exploration of glycoside phosphorylases.

GH94 along with GH112 exclusively comprises glycoside phosphorylases unlike GH13, GH65, and GH130 and follows inverting mechanism. Cellobiose phosphorylase (CBP)11,12, cellodextrin phosphorylase13, laminaribiose phosphorylase14, and 1,2-β-oligoglucan phosphorylase (SOGP, “S” means the initial letter of “sophoro-”oligosaccharide representing “β-1,2-gluco-”oligosaccharide.)15, which are members of the GH94 family, share α-d-glucose-1-phosphate (G1P) as a common donor substrate for the synthetic reaction. Recently, cellobionic acid phosphorylase (CBAP), which utilizes gluconic acid as an acceptor substrate, has been reported16. The family also contains chitobiose phosphorylase (ChBP) that acts on an chitobiose (GlcNAc-β-1,4-GlcNAc) and produces α-N-acetyl-d-glucosamine-1-phosphate through phosphorolysis17. CBP, ChBP and CBAP each form a dimer and show a similar overall quaternary structure, though the amino acid sequence identities between them are relatively low (<30%). They also share the position of the catalytic pocket, which is formed at the dimer interface between the N-terminal domain (Ndom) and the catalytic domain of another subunit, although their acceptor recognition sites are diverse18,19,20. In contrast to these glycoside phosphorylases acting on β-1,4-linked glycosides, no structure of a glycoside phosphorylase acting on β-1,2-glucan and β-1,3-glucan is available.

SOGP is an enzyme given a new EC number (EC 2.4.1.333) according to our recent study on SOGP from Listeria innocua (LiSOGP)15. LiSOGP phosphorolyzes β-1,2-glucooligosaccharides (alternatively sophorooligosaccharides, Sops) with degrees of polymerization (DP) of 3 or more. The high specificity of LiSOGP to SopNs (N denotes DP) suggests involvement of the enzyme in β-1,2-glucan metabolism together with a β-glucosidase encoded by an adjacent gene21,22. One of the most remarkable features of LiSOGP homologs is the approximately 250 additional amino acid residues at their N-terminus. This region is supposed to be important for substrate specificity, since it is fully conserved among LiSOGP homologs. However, no LiSOGP homolog has been characterized to date.

Lachnoclostridium phytofermentans (formerly, Clostridium phytofermentans) is an anaerobic bacterium that is able to metabolize various kinds of plant polysaccharides23. The bacterium possesses many genes encoding glycoside phosphorylases including five genes belonging to the GH94 family. One of these genes is an SOGP gene homolog (Cphy_0694, LpSOGP). In this study, we characterized the enzymatic properties of LpSOGP to clarify the features of the SOGP group. Furthermore, we also determined the crystal structure of LpSOGP to understand the structure-function relationship and factors relevant to differences in substrate specificity between other enzymes in the GH94 family.

Results

Biochemical characterization of LpSOGP

In the GH94 family, classification based on substrate specificity is almost consistent with phylogenetic grouping15. LpSOGP shows 39% amino acid sequence identity with LiSOGP and belongs to the same group as it. We evaluated the general properties of LpSOGP using Sop2 as a substrate for the synthetic reaction. The optimum temperature and pH of LpSOGP were 40 °C and pH 7, respectively. LpSOGP was stable in the pH range of 6.5–8.0 (more than 80% residual activity) and up to 37 °C. LpSOGP showed similar Km and kcat values for Sop2, Sop3, and Sop4, but no significant activity toward Glc in the synthetic reaction (Table 1). Regarding phosphorolytic activity, LpSOGP showed equivalent Km and kcat values for Sop3, Sop4, and Sop5 to those in the synthetic reaction and showed no activity toward Sop2. This kinetic analysis indicates that LpSOGP has essentially the same chain length specificity as to SopNs as LiSOGP. LpSOGP showed sufficiently high kcat/Km values for G1P and inorganic phosphate (Pi) as a GH family enzyme, though the Km value for Pi was a little higher than that on LiSOGP. A double reciprocal plot for phosphorolysis of Sop3 suggests that LpSOGP follows a sequential Bi Bi mechanism (Fig. S1). LpSOGP showed very weak activity against laminaribiose and no activity toward other disaccharides such as cellobiose or monosaccharides in the synthetic reaction on TLC analysis (Fig. S2A–C). In addition, LpSOGP did not show phosphorolytic activity toward cellobiose or laminaribiose (Fig. S2D). These results indicate that LpSOGP is highly specific to SopNs, as LiSOGP is15, and is completely different from other GH94 enzymes in substrate specificity.

Table 1. Kinetic parameters of LpSOGP for SopNs.

| Synthesis |

Phosphorolysis |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kcat | Km | kcat/Km | kcat | Km | kcat/Km | ||

| (s−1) | (mM) | (s−1 mM−1) | (s−1) | (mM) | (s−1 mM−1) | ||

| Glc | N.D.a | — | — | — | |||

| Sop2 | 40 ± 3 | 5.5 ± 0.9 | 7.3 ± 0.6 | N.D. | |||

| Sop3 | 55 ± 1 | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 20 ± 1 | 47 ± 5 | 4.8 ± 0.8 | 9.8 ± 0.6 | |

| Sop4 | 46 ± 3 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 21 ± 2 | 42 ± 3 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 23 ± 2 | |

| Sop5 | —b | — | — | 48 ± 3 | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 19 ± 1 | |

| G1P | 28 ± 1 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 11 ± 1 | Pi | 63 ± 2 | 11 ± 1 | 5.7 ± 0.1 |

Synthetic and phosphorolytic reactions were performed at pH 7.0 and 7.5, respectively.

aN.D. indicates that specific activity is less than 0.1% of that for Sop3 when 10 mM substrates is used.

b− represents not examined.

Overall structure

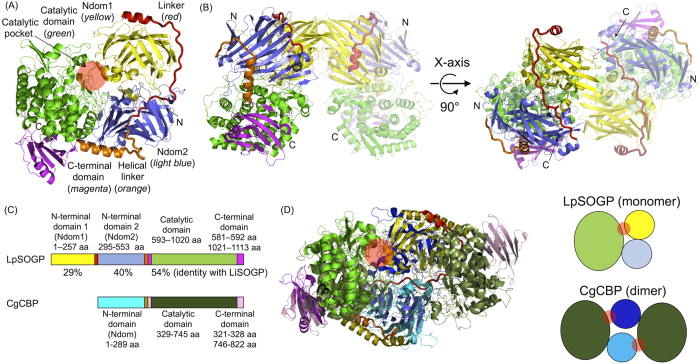

The crystal structure of apo LpSOGP was determined at 2.0 Å resolution (Table S1). The crystals contain two identical molecules in an asymmetric unit. The tertiary structure consists of four domains: two N-terminal β-sandwich domains (residues 1–257, yellow, Ndom1; and 295–553, light blue, Ndom2), a catalytic (α/α)6 barrel domain (593–1020, green), and a β sheet domain (magenta). The β sheet domain consists of a middle segment (581–592) and a C-terminal segment (1021–1113). Ndom2 and the catalytic domain are connected through a helical linker region (554–580, orange), and Ndom1 and Ndom2 are connected through a linker composed of a helix and a long loop (258–294, red) (Fig. 1A). The helix is included in the linker region due to the alignment with CBAP, ChBP, and CBP. The two molecules in the asymmetric unit are in contact with each other mostly in the Ndom1 region (Fig. 1B). The contact area is only 2.5% (935.5 Å2) of the monomer surface area. The estimated ΔGdiss is a negative value (−11.2 kcal/mol), which suggests that the dissociated state is more stable, based on analysis using the protein-protein interaction interface server (PISA, http://www.ebi.ac.uk/msd-srv/prot_int/pistart.html)24. In addition, LpSOGP was eluted at the retention time of 100 kDa on size-exclusion chromatography. These results indicate that LpSOGP is a monomeric enzyme, as LiSOGP is15.

Figure 1. Overall structure of LpSOGP.

(A) Domain constitution of the LpSOGP monomer. The colors of domains and linkers in LpSOGP are shown in the figure. In the other figures, the same color usage as for LpSOGP is used. Loops in linkers are shown as thick lines. The catalytic pocket is shown as a red circle (A,D). The positions of the N and C-termini are indicated by arrows (A,B). (B) Asymmetric unit of LpSOGP. One subunit in an asymmetric unit is presented semitransparent. (C) Comparison of domain constitutions between LpSOGP and CgCBP. The values of percentages indicate the amino acid sequence identity with the corresponding domain in LiSOGP. The N-terminal domain, catalytic domain, C-terminal domain, and helical linker of CgCBP are shown in cyan, deep green, light pink, and light brown, respectively. (D) (left) Superimpositioning of the LpSOGP monomer and CgCBP dimer. LpSOGP without Ndom1 and the CgCBP monomer are aligned. The color usage for CgCBP is as in (C) except that the N-terminal domains of CgCBP are shown in cyan and blue. (right) Schematic structures of LpSOGP and CgCBP. Linkers and the C-terminal domain are omitted.

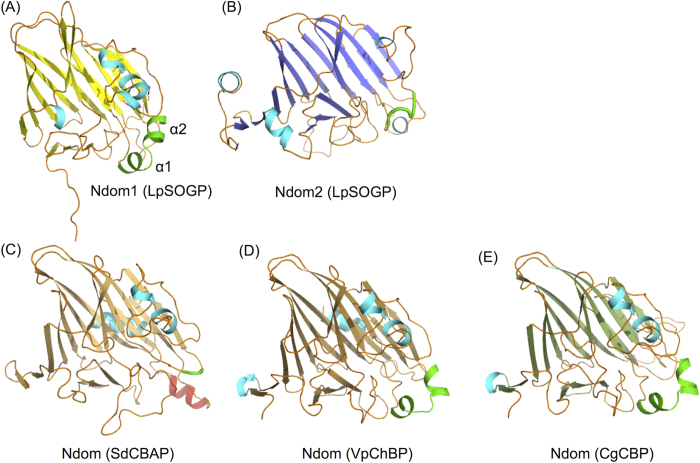

The overall structure of LpSOGP besides Ndom1 is basically similar to those of GH94 CBAP from Saccharophagus degradans (SdCBAP), ChBP from Vibrio proteolyticus (VpChBP), and CBP from Cellvibrio gilvus (CgCBP) (the RMSD values are 4.11, 3.53, and 3.29 Å, respectively). Ndom1 is unique to LpSOGP, being missing in CBP, ChBP, and CBAP (Fig. 1C). It is interesting that Ndom1 in LpSOGP occupies the same position as the Ndom in subunit B of CgCBP, when subunit A in the CgCBP dimer and the corresponding region of LpSOGP (all except for Ndom1, residues 295–1113) are superimposed (Fig. 1D left). This structural observation suggests that LpSOGP forms a catalytic pocket within its tertiary structure unlike the other three GH94 enzymes (Fig. 1D right). The structure of Ndom1 is similar to those of both Ndom2 and Ndoms (Fig. 2), though Ndom1 shows low sequence identity with them (<15%) (Table 2). It should be noted that Ndoms in CgCBP, VpChBP, and SdCBAP are similar to Ndom1 rather than Ndom2 in both the primary and 3D structures (Table 2, Fig. 2). On the contrary, the amino acid sequence identity of Ndom1 in LpSOGP with the corresponding region in LiSOGP (29%) is lower than that of Ndom2 (40%) (Fig. 1C). As for the substrate recognition region, two helices (α1 and α2) in Ndom1 constitute a part of the catalytic pocket as well as in Ndoms in VpChBP and CgCBP (Figs 2A,D,E and 3A). The corresponding region in Ndom2 is a short loop like that of SdCBAP, but the substrate recognition helix of SdCBAP is not conserved in Ndom2 (Figs 2B,C and 3B).

Figure 2. N-Terminal domains of LpSOGP, SdCBAP, VpChBP, and CgCBP.

Loops and helices are shown in orange and cyan. β-Sheets in Ndom1 (A), Ndom2 (B), Ndoms of SdCBAP (C), VpChBP (D), and CgCBP (E) are shown in yellow, light blue, light orange, brown, dark green, respectively. The region important for substrate recognition in Ndom1, and the corresponding positions in Ndom2 and Ndoms are represented in green. The helix important for substrate recognition in SdCBAP is shown in red.

Table 2. Amino acid sequence identity and RMSD among N-terminal domains in GH94 enzymes.

| Enzyme | Domain | Sequence identity (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LpSOGP | SdCBAP | VpChBP | CgCBP | ||||

| Ndom1 | Ndom2 | Ndom | Ndom | Ndom | |||

| (Cat) | (Cat) | (Cat) | (Cat) | ||||

| 5H3Za | 4ZLFa | 1V7Xa | 2CQSa | ||||

| RMSD for Cα (Å) | LpSOGP | Ndom1 | 11 | 14 | 14 | 10 | |

| LpSOGP | Ndom2 (Cat)b | 3.71 | 4.6 (18) | 7.8 (17) | 8.8 (16) | ||

| SdCBAP | Ndom (Cat) | 3.03 | 3.79 (2.77) | 20 (26) | 13 (25) | ||

| VpChBP | Ndom (Cat) | 2.59 | 3.40 (2.86) | 2.53 (2.25) | 38 (35) | ||

| CgCBP | Ndom (Cat) | 2.60 | 3.45 (2.62) | 2.59 (1.98) | 1.35 (1.84) | ||

The values are based on pairwise alignment using Matras (http://strcomp.protein.osaka-u.ac.jp/matras/)43.

The represents 100% for sequence identity and 0 Å for RMSD.

The regions of N-terminal domains and catalytic domains in SdCBAP, VpChBP, and CgCBP are SdCBAP (residues 1–275 and 318–709), VpChBP (1–269 and 310–724), and CgCBP (1–270 and 328–746), respectively.

aPDB IDs whose structures were used for preparation of figures and tables.

bThe values in parentheses are the results calculated on alignment of catalytic domains.

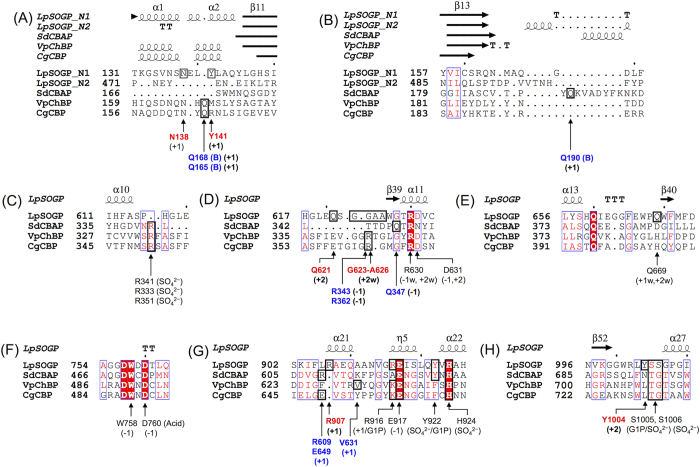

Figure 3. Multiple alignment of GH94 enzymes.

Multiple alignment was performed using Matras43. Figures were prepared using Espript 3.0 in the ENDscript server (http://espript.ibcp.fr)44. (A–B) Ndom1 and Ndom2 in LpSOGP, and Ndoms in SdCBAP, VpChBP, and CgCBP are aligned. (C–H) The catalytic domains of LpSOGP, SdCBP, VpChBP, and CgCBP are aligned. Residues related with substrate recognition are labeled, boxed, and indicated by arrows. Residues important for substrate binding at subsites +1 and +2 in LpSOGP are shown in red bold letters. Blue bold letters represent the residues in SdCBAP, VpChBP, and CgCBP that are located at the positions corresponding to the LpSOGP residues shown in red bold letters. Parentheses are the ligands with which the residues interact or the subsites where the residues bind to the ligands. Letters “w” in parentheses indicate that binding to the ligand is mediated by water molecules. (Acid) means that the residue is a catalytic acid. The residues derived from the B subunit are indicated by bold letter of B in parentheses.

Complex structures with ligands

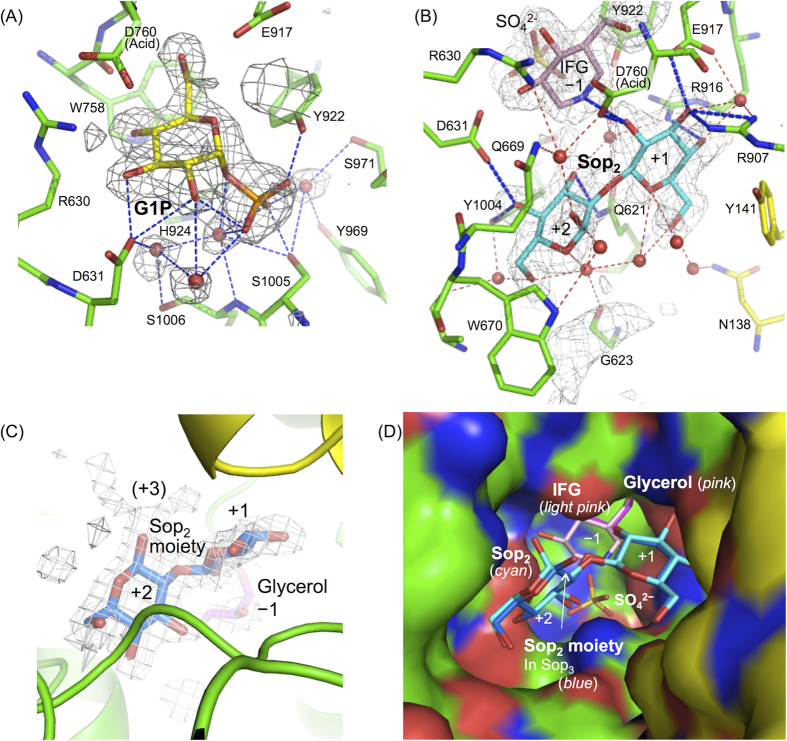

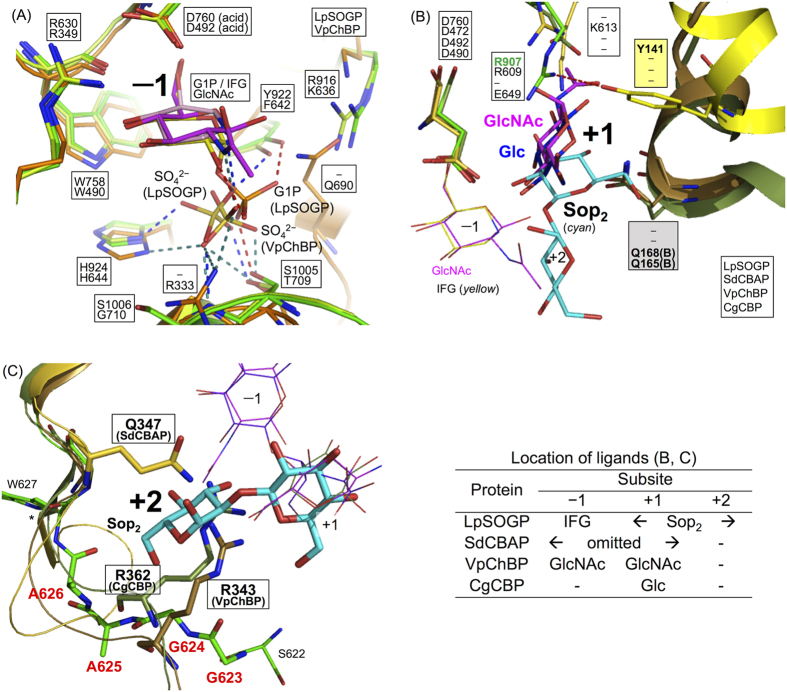

In order to understand the substrate recognition mechanism, the crystal structures of LpSOGP in complexes with G1P, Sop2 (with isofagomine d-tartrate (IFG) and (NH4)2SO4), and Sop3 (with (NH4)2SO4) were determined at 2.1, 2.0 and 2.2 Å resolution, respectively (Table S1). In the complex structure with G1P, the electron density of G1P was clearly observed at subsite −1. It is noteworthy that this is the first reported structure of an inverting glycoside phosphorylase complexed with a sugar-phosphate substrate. The Glc moiety in the G1P molecule undergoes direct interactions with R630, D631, W758, D760, and E917 (Figs 3 and 4A), all of which are highly conserved in GH94 enzymes. The position of the Glc moiety is well superimposed with ligands at subsite −1 in other GH94 enzymes such as GlcNAc in VpChBP (Fig. 5A). The phosphate moiety of the G1P molecule forms hydrogen bonds with Y922, S1005, and three water molecules (Figs 3 and 4A). Contrarily, the moiety does not form hydrogen bonds with H924 and S1006 (main chain) that correspond with the reported SO42−-recognizing residues (H624 and G710, respectively, in the case of VpChBP). This is because the phosphate moiety is slightly deviated from the position of SO42− in VpChBP and CgCBP (1.1 Å and 1.5 Å, respectively) (Fig. 5A).

Figure 4. Complex structures of LpSOGP.

(A–C) Electron density maps of G1P (A), Sop2/IFG/SO42− (B), and Sop3 (C). The Fo−Fc electron density maps of the ligands are presented as a gray mesh (contoured at 3.0σ). Ligands are omitted for calculation of the Fo−Fc maps. The ligands and residues important for substrate recognition are shown as sticks. The color usage for LpSOGP follows Fig. 1. Water molecules are shown as red spheres. Hydrogen bonds between ligands and residues are represented by blue dotted lines. Hydrogen bonds that water molecules participate in Sop2 recognition are shown as red dotted lines in (B). The positions of subsites are shown. The parentheses in (C) indicate that the position of subsite +3 is putative. G1P (A), Sop2 (B), IFG (B), the Sop2 moiety (C), and glycerol are shown in yellow, cyan, light pink, blue, and pink, respectively. (D) Ligands in a catalytic pocket. The structures in (B) and (C) are superimposed and the structure in (B) is shown as a surface representation.

Figure 5.

Comparison of subsites −1 (A), +1 (B) and +2 (C). Proteins are represented as cartoons. Glc in CgCBP, and GlcNAc in VpChBP, SdCBAP, VpChBP and CgCBP are shown in blue, magenta, light brown, brown, and dark green, respectively. The color usage for the other components follows previous figures. Labeled residues, ligands in (A), GlcNAc at subsite +1 and Glc in (B), and Sop2 are shown as sticks. The other ligands are shown as lines. Hyphens in square boxes indicate that there is no corresponding residue. (A) Ligands except at subsite −1 are omitted. Hydrogen bonds formed by the phosphate moiety in G1P, SO42− molecules in LpSOGP and VpChBP are represented in red, blue, and green dotted line. (B) Hydrogen bonds between R907 and Y141 are shown as a red dotted line. Ligands in SdCBAP are omitted. (C) Residues without a boxed label are derived from LpSOGP. The region important for formation of subsite +2 in LpSOGP is shown as a stick and residues in the region are labeled in red bold letters. An asterisks indicates that the region beyond the asterisk is omitted for visibility. The table shows the locations of ligands in (B) and (C).

Subsites +1 and +2 were revealed by the complex structure with IFG, Sop2, and (NH4)2SO4. IFG is located at subsite −1, since IFG is well superimposed with the Glc moiety of G1P (Fig. 5A). In addition, the position of SO42− is almost identical with that in VpChBP. Only the electron density of the α-anomer of Sop2 is observed adjacent to IFG (Fig. 4B). The 2-OH group in the non-reducing end glucoside and the 1-OH group in the reducing end glucoside of Sop2 face subsite −1 and outside the substrate pocket, respectively. Dihedral angles φ (O5-C1-O1-C’2) and ψ (C1-O1-C’2-C’1) in the Sop2 molecule are −69.7° and 146.5°, respectively. The corresponding angles of a free Sop2 structure whose energy is minimized25 are similar (−72° and 114°, respectively). The conformations of glucosides at both subsites are 4C1. These facts mean that Sop2 binds to LpSOGP with only a little distortion, suggesting that Sop2 is bound at subsites +1 to +2 productively. Sop2 forms 8 hydrogen bonds with Q621, D631, and Y1004 (for binding at subsite +2), and D760, R907, R916, and IFG (for binding at subsite +1) directly. Sop2 also undergoes interactions with R630, A626, G623, D760, N138, Q621, and E917 indirectly through the 8 hydrogen bonds with water molecules. Y141 constitutes the substrate pocket by forming a hydrogen bond with R907, though the residue forms no hydrogen bond with Sop2.

The Sop3 (with (NH4)2SO4)-soaked structure shows clear electron density for the Sop2 moiety at subsites +1 and +2 (Fig. 4C). The Glc moiety at subsite +2 is a β-anomer unlike in the case of Sop2 soaking, though two ligands at subsites +1 and +2 are well superimposed (Fig. 4C,D), suggesting that Sop3 is bound at subsites +1 to +3. However, since weak electron density was observed beyond the 1-OH group of the glucose moiety at subsite +2, Sop3 appears to be mostly disordered at subsite +3. The disorder at subsite +3 is perhaps due to fewer hydrogen bond interactions than at subsites +1 and +2. These observations are consistent with the similar kinetic parameters for Sop2–5. The electron density of glycerol was observed at subsite −1. The glycerol molecule is well superimposed with a part of IFG at subsite −1 (Fig. 4D). The SO42− ion was not observed in the catalytic pocket perhaps due to precipitation of ligands in the soaking solution. Overall the reaction mechanism of LpSOGP is proposed as shown in Fig. S3.

Discussion

In this study, we identified the function of LpSOGP, determined its crystal structure, which is the first one among phosphorylases acting on β-linked glucan, and clarified the binding modes of substrates. The similarity between LpSOGP and LiSOGP in enzymatic function and the conserved substrate recognition residues among SOGP homologs (Fig. S4) imply that this group of SOGP homologs shares essentially the same substrate specificity. The structures of LpSOGP enable us to discuss the molecular mechanism of substrate specificity through comparison with those of other structurally available GH94 enzymes. Since many residues related with substrate recognition at subsite −1 and the catalytic acid (D760) are highly conserved among GH94 enzymes spatially (Fig. 5A), these residues were aligned to compare subsites +1 and +2 between LpSOGP and the other enzymes, SdCBAP, VpChBP, and CgCBP (Fig. 3).

The most remarkable difference between LpSOGP, and VpChBP and CgCBP at subsite +1 is the orientation of the ligands (Fig. 5B). Although the Glc moiety in LpSOGP at subsite +1 is located at a similar position to both the GlcNAc molecule in VpChBP and the Glc molecule in CgCBP, the Glc moiety in LpSOGP is rotated by more than 120° about its C2-O2 bond involved in its glycosidic linkage from the molecules in CgCBP and VpChBP. In LpSOGP, this rotation allows the anomeric position of the Glc moiety at subsite +1 to be oriented toward the open space in the catalytic pocket but not toward the wall of the pocket (Figs 4D and 5B). In LpSOGP, R907 protruding to subsite +1 and Y141 forming a hydrogen bond with R907 occupy a position that is able to hinder the binding of the Glc molecule in CgCBP and the GlcNAc molecule in VpChBP sterically. On the other hand, the positions of Q168 (VpChBP) and Q165 (CgCBP) can cause steric hindrance to the Sop2 in LpSOGP. The spatial positions of these residues explain the clear difference in substrate binding mode, though these residues correspond in the primary sequences (Fig. 3A). In addition, the positions of these residues depend on the orientations of helices shown in Fig. 5B.

In LpSOGP, the substrate inversion at subsite +1 is likely a key factor for substrate specificity, as described below. The dihedral angle of C1(IFG)-O’2 (Sop2)-C’2-C’1 (corresponding to ψ between subsite −1 and +1) is −46.0°, suggesting that the torsion angle of a glycosidic bond between subsites −1 and +1 is obviously different from that of energy-minimized Sop2 (114°)25 and is unfavorable for substrate binding. In addition, the dihedral angle (ψ) of Sop2 in LiBGL, a Sop2-degrading β-glucosidase, is also quite different (159.8°)22. However, binding of a Glc moiety to subsite +1 itself appears not to compensate for the disadvantage, since no electron density derived from Glc was observed even on soaking with 1 M Glc (data not shown). This is consistent with the fact that the number of direct interactions with Sop2 at subsite +1 is fewer than those in other GH94 phosphorylases (Table S2). The disadvantage for substrate binding is likely compensated for at subsite +2, since the glycosidic bond in the Sop2 molecule (between subsites +1 and +2) is distorted only a little. Considering the substrate binding of CBP, the dihedral angle of cellobiose (subsites −1 and +1) in CBP from Cellulomonas uda (CuCBP) is φ = −82.5° and ψ = 65.0° (PDB ID: 3S4A), being within the range of stable conformation of a free cellobiose molecule25. The position and the orientation of the Glc moiety at subsite +1 are similar to those of the Glc molecule in CgCBP. This is consistent with substrate specificity of the CBPs. Overall, the combination of “the inversion at subsite +1” and “the compensation at subsite +2” defines the substrate specificity of LpSOGP.

The architecture at subsite +2 is unique in LpSOGP, compared with in SdCBAP, VpChBP, and CgCBP. The small side chains of Gly and Ala residues provide LpSOGP with sufficient space as subsite +2. On the contrary, Q347 (SdCBAP), R343 (VpChBP), and R362 (CgCBP) protrude to subsite +2 to fill the space and interact with the ligands at subsites −1 and/or +1 (Figs 3D and 5C). In CuCBP, the side chain of the Arg residue corresponding to R362 (CgCBP) is flipped out despite that cellobiose binds to CuCBP26. This flipping makes a space corresponding to subsite +2 of LpSOGP, which is consistent with the fact that CuCBP allows gentiobiose (Glc-β-1,6-Glc) and melibiose (Glc-α-1,6-Glc) to be minor acceptor substrates27. These observations imply an evolutional relationship between SOGP and other GH94 enzymes.

Ndom1 appears to be generated through domain duplication according to its position and the structural similarity to Ndom2. This duplication monomerizes LpSOGP but retains the fundamental constitution of a catalytic pocket between hetero domains. Such an example is found in isocitrate dehydrogenases28. A class II ribonucleotide reductase is another example, though only a part of the domain is duplicated29. This evolutional pathway is reversed against oligomerization through swapping of duplicated domains30,31. Among carbohydrate-active enzymes, the monomeric constitution of GH55 β-1,3-glucanase from Phanerochaete chrysosporium composed of tandem β-helical domains seems to be caused by domain duplication32,33. However, the catalytic domain is located at the interface of the two structurally homologous domains unlike in the case of LpSOGP.

This study clearly provides mechanistic insights into the substrate specificity of LpSOGP, which is an important structural basis for enzymes acting on β-1,2-linked glucosidic bonds. The domain duplication found in LpSOGP is a unique example in carbohydrate-active enzymes and expands the knowledge on molecular evolution.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of recombinant LpSOGP

A gene encoding LpSOGP (cphy_0694, GenBankTM accession number ABX41081.1) was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA of L. phytofermentans as a template using KOD-plus DNA polymerase (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) with the following oligonucleotides based on the genomic sequence (GenBankTM accession number CP000885): 5′-aaaccatgggcatactaaaaacattgtctg-3′ as the forward primer containing an NcoI site (underlined) and 5′-tttctcgaggttcttaacataaatatg-3′ as the reverse primer containing an XhoI site (underlined). The amplified PCR product was purified using a QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), digested with NcoI and XhoI (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA, USA), and inserted into the corresponding sites of pET28a (+) (Novagen, Madison, WI, USA) to encode a His6-tagged fusion at the C-terminus of the recombinant protein. The expression plasmid was propagated in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) (Novagen), purified using a High Pure Plasmid Isolation Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), and verified by sequencing (Eurofins Genomics K.K., Tokyo, Japan). The transformant was cultured in LB medium containing 30 μg/ml of kanamycin at 37 °C until OD660 reached around 0.8. After 0.1 mM IPTG (final concentration) was added to produce recombinant LpSOGP, the cells were cultured at 20 °C overnight. The cells were collected by centrifugation at 3900× g for 5 min, suspended in 50 mM MOPS-NaOH (pH 7.5) buffer containing 300 mM NaCl (buffer A), and then disrupted by sonication. The supernatant obtained on centrifugation at 27000× g for 10 min was loaded onto a HisTrap FF crude column (5 ml; GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, England) equilibrated with buffer A. After the column had been washed with buffer A containing 10 mM imidazole till almost unbound proteins were removed, LpSOGP was eluted with a linear gradient of imidazole (10–300 mM, 55 ml total volume) in the same buffer at a flow rate of 2 ml/min. The eluate was buffered with 20 mM MOPS-NaOH (pH 7.5) using Amicon Ultra 30,000 molecular weight cut-off (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) for assaying. For crystallization, the enzyme solution mixed with an equal volume of 50 mM MOPS-NaOH (pH 7.5) containing 60% saturated ammonium sulfate was loaded onto a HiTrapTM Butyl HP column (5 ml; GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 50 mM MOPS-NaOH (pH 7.5) containing 30% saturated ammonium sulfate. The enzyme was eluted with a linear gradient of 30–0% saturated ammonium sulfate (55 ml total volume) in 50 mM MOPS-NaOH (pH 7.5) at a flow rate of 2 ml/min. The eluate was buffered with 5 mM MOPS-NaOH buffer (pH 7.5) using Amicon Ultra 30,000 molecular weight cut-off to concentrate the enzyme to 10 mg/ml. An ÄKTA Prime Plus chromatography system (GE Healthcare) was used for the whole enzyme purification steps. The purity of the enzyme was analyzed by SDS-PAGE using 8% polyacrylamide gels. Protein concentrations were determined from UV absorbance at 280 nm (the extinct coefficient34 and theoretical molecular weight of LpSOGP are 167890 cm−1M−1 and 169640 Da, respectively). For expression of selenomethionine (SeMet)-labeled LpSOGP, the plasmid was introduced into E. coli B834(DE3). LeMaster medium containing 30 μg/ml kanamycin was used in place of LB medium. Protein induction and purification were performed in almost the same way as for the native protein.

Assay

The phosphorolytic activity of LpSOGP was determined by quantifying G1P produced from SopNs and 10 mM inorganic phosphate by coupling assay using phosphoglucomutase and glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase35. The colorization reagent and substrate solution (85 μl) comprising SopNs, inorganic phosphate, 10 μM glucose-1,6-bisphosphate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 10 IU/mL glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase from Leuconostoc sp. (Oriental Yeast, Tokyo, Japan), 12.5 IU/mL phosphoglucomutase from rabbit muscle (Sigma-Aldrich), 1.0 mM thio-NAD+ (Oriental Yeast), 50 mM MgCl2, and 100 mM MOPS-NaOH (pH 7.5) was mixed with 85 μl of the enzyme solution in 20 mM MOPS-NaOH (pH 7.5) to start the reaction in a 96-well microplate (EIA/RIA plate, 96-well half area; Corning, NY, USA). The reaction mixture was incubated at 30 °C and the increase in absorbance at 400 nm due to thio-NADH was monitored at 1-minute interval for 10 min with a Spectramax 190 (Molecular Devices, CA, USA).

Synthetic activity was determined by measuring inorganic phosphate produced from acceptors and 10 mM G1P by the Lowry and Lopez method36. The substrate solution comprising various concentrations of SopNs and 10 mM G1P in 100 mM MOPS-NaOH (pH 7.0) (140 μl) was mixed with 20 μl of enzyme solution to start the reaction at 30 °C. Aliquots (20 μl) were taken at 2-minute intervals and was mixed with 160 μl of 0.2 M sodium phosphate (pH 4.0) and 25 mM ammonium molybdate containing 25 mM sulfuric acid to stop the reaction. The solutions were mixed with 20 μl of 1% ascorbic acid containing 0.05% potassium sulfate. After the solution had been incubated at 37 °C for 1 h, the increase in absorbance at 700 nm was measured.

For investigation of substrate specificity, the synthetic reaction was performed using a substrate solution containing 10 mM each acceptor substrate and 10 mM G1P in the presence of 100 mM MOPS-NaOH (pH 7.0). Substrates are altered to 10 mM each oligosaccharide and 10 mM inorganic phosphate for phosphorolysis. The concentration of LpSOGP was 0.1 mg/ml when Sop2 and Sop3 were used as substrates and 1.0 mg/ml for the other substrates. The reaction solution was incubated at 30 °C for 1 h and then the reaction was stopped by heat treatment at 100 °C for 5 min. The reaction products were analyzed by thin layer chromatography (TLC).

Temperature and pH profiles

The effects of temperature and pH on activity were evaluated as to the synthetic activity using 10 mM Sop2 and 10 mM G1P. The optimum temperature and pH were determined by measuring the activity at various temperatures (0–60 °C) and in various pH ranges in 20 mM buffers, respectively, as follows: sodium acetate (pH 4.0–5.5), MES-NaOH (pH 5.5–6.5), MOPS-NaOH (pH 6.5–7.5), Tris-HCl (pH 7.5–9.0), and glycine-NaOH (pH 9.0–10.0). The thermal and pH stabilities were determined from the residual synthetic activity at 30 °C after incubation of LpSOGP (0.5 mg/ml) at various temperatures (0–60 °C) in 100 mM MOPS-NaOH (pH 7.5), and at 37 °C in 20 mM various buffers as described above, respectively.

TLC analysis

Each reaction solution (0.5 μl) was spotted onto a TLC plate (Kieselgel 60 F254; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). The TLC plates were developed with 75% acetonitrile in water (v/v). The TLC plates were then soaked in a 5% sulfuric acid:95% ethanol (v/v) solution and heated in an oven until bands were sufficiently visible.

Kinetic analysis

The initial velocities of the synthetic and phosphorolytic reactions with various concentrations of substrates were determined under the standard conditions. The kinetic parameters for SopNs were calculated by curve fitting the experimental data to the Michaelis-Menten equation (1) using GraFit version 7.0.3.

|

where v is reaction velocity, kcat is turnover number, Km is Michaelis constant, [E]0 is enzyme concentration, and [S] is substrate concentration.

Size-exclusion chromatography

LpSOGP (2 mg/ml) was loaded onto a SuperdexTM 200 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) containing 150 mM NaCl. Ovalbumin (44 kDa), conalbumin (75 kDa), aldolase (158 kDa), ferritin (440 kDa), and thyroglobulin (669 kDa; GE Healthcare) were used as standard proteins. Blue dextran 2000 (2000 kDa; GE Healthcare) was used to determine the void volume of the column.

Crystallography

All crystals (native and SeMet-labeled protein) used for data collection were obtained at 25 °C using the hanging drop vapor diffusion method by mixing 1–2.4 μl of 10 mg/ml protein solution with an equal volume of reservoir solution comprising 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 0.2 M calcium acetate, and 10–15% PEG3350. Crystals completely grew in 2–3 days. Crystals were cryoprotected with the reservoir solution containing 30% glycerol for the SeMet-substituted enzyme or 25% PEG400 for the native enzyme. A cryoprotectant containing MgCl2 instead of calcium acetate was used to avoid precipitation of ligands when crystals were soaked with soaking solution containing G1P or IFG (Toronto Research Chemicals Inc., Toronto, Canada), Sop2, or (NH4)2SO4. IFG was selected as a glucose analog, since it strongly inhibited the synthetic reaction of SOGP in a preliminary experiment. Crystals were then soaked in the cryoprotectants supplemented with 50 mM Sop3 (with 50 mM (NH4)2SO4) (SeMet-labeled), 20 mM G1P (native), or 20 mM Sop2 (with 1.0 mM IFG and 100 mM (NH4)2SO4) (native). In the case of soaking in 50 mM Sop3 (with 50 mM (NH4)2SO4), precipitation in the soaking solution made the concentrations of the ligands obscure. The crystals were cooled and then kept at 100 K in a nitrogen-gas stream during data collection. A set of X-ray diffraction data for each crystal was collected using a CCD detector (ADSC Quantum 210r) on a beamline BL-5A at Photon Factory (Tsukuba, Japan). The diffraction data set was processed using iMosflm37 or HKL200038. The initial phase of the LpSOGP apo structure was determined by the single wavelength anomalous dispersion method using AutoSol in Phenix39. Automated model building was also performed using the same program. Molecular replacement was performed using MOLREP40 to determine the initial phases of complex structures. Manual model building and refinement were performed using Coot41 and Refmac542, respectively. Quality checking of the structures was performed using the wwPDB validation server (http://wwpdb-validation.wwpdb.org/validservice/). PyMOL (DeLano Scientific; http://www.pymol.org) was used for the preparation of figures. The buried surface area was calculated with PISA24.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Nakajima, M. et al. Mechanistic insight into the substrate specificity of 1,2-β-oligoglucan phosphorylase from Lachnoclostridium phytofermentans .Sci. Rep. 7, 42671; doi: 10.1038/srep42671 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was performed with the approval of the Photon Factory Program Advisory Committee (Proposal Nos 2012G108 and 2014G509). Dr. Motomitsu Kitaoka kindly provided the materials for crystallization and several ideas for discussion. Hiroyuki Toyoizumi, Keisuke Sudo, and Shiori Saito helped us to optimize the crystallization conditions.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions M.N., A.M., S.F., H.T., and H.N. wrote the main manuscript text. M.N., N.T., N.F., T.N., Y.K., Y.T., N.S., and S.F. performed the experiments. M.N., H.T., and H.N. conceived and designed the experiments.

References

- Kawahara R. et al. Metabolic mechanism of mannan in a ruminal bacterium, Ruminococcus albus, involving two mannoside phosphorylases and cellobiose 2-epimerase: discovery of a new carbohydrate phosphorylase, β-1,4-mannooligosaccharide phosphorylase. J Biol Chem 287, 42389–42399 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladevèze S. et al. Role of glycoside phosphorylases in mannose foraging by human gut bacteria. J Biol Chem 288, 32370–32383 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yernool D. A., McCarthy J. K., Eveleigh D. E. & Bok J. D. Cloning and characterization of the glucooligosaccharide catabolic pathway β-glucan glucohydrolase and cellobiose phosphorylase in the marine hyperthermophile Thermotoga neapolitana. J Bacteriol 182, 5172–5179 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitaoka M. & Hayashi K. Carbohydrate-processing phosphorolytic enzymes. Trends Glycosci Glycotechnol 14, 35–50 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Abe K. et al. Large-scale preparation of 1,2-β-glucan using 1,2-β-oligoglucan phosphorylase. J Appl Glycosci 62, 47–52 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima M., Nishimoto M. & Kitaoka M. Practical preparation of d-galactosyl-β1 → 4-l-rhamnose employing the combined action of phosphorylases. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 74, 1652–1655 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitaoka M. Diversity of phosphorylases in glycoside hydrolase families. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 99, 8377–8390 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantarel B. L. et al. The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes database (CAZy): an expert resource for Glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res 37, D233–238 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakai H., Kitaoka M., Svensson B. & Ohtsubo K. Recent development of phosphorylases possessing large potential for oligosaccharide synthesis. Curr Opin Chem Biol 17, 301–309 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald S. S., Blaukopf M. & Withers S. G. N-acetylglucosaminidases from CAZy family GH3 are really glycoside phosphorylases, thereby explaining their use of histidine as an acid/base catalyst in place of glutamic acid. J Biol Chem 290, 4887–4895 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. K., Kitaoka M., Krishnareddy M., Mori Y. & Hayashi K. Kinetic studies of a recombinant cellobiose phosphorylase (CBP) of the Clostridium thermocellum YM4 strain expressed in Escherichia coli. J Biochem 132, 197–203 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitaoka M., Sasaki T. & Taniguchi H. Synthetic reaction of Cellvibrio gilvus cellobiose phosphorylase. J Biochem 112, 40–44 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichenbecher M., Lottspeich F. & Bronnenmeier K. Purification and properties of a cellobiose phosphorylase (CepA) and a cellodextrin phosphorylase (CepB) from the cellulolytic thermophile Clostridium stercorarium. Eur J Biochem 247, 262–267 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitaoka M., Matsuoka Y., Mori K., Nishimoto M. & Hayashi K. Characterization of a bacterial laminaribiose phosphorylase. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 76, 343–348 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima M. et al. 1,2-β-Oligoglucan phosphorylase from Listeria innocua. PLoS One 9, e92353 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nihira T. et al. Discovery of cellobionic acid phosphorylase in cellulolytic bacteria and fungi. FEBS Lett 587, 3556–3561 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda Y., Kitaoka M. & Hayashi K. Reaction mechanism of chitobiose phosphorylase from Vibrio proteolyticus: identification of family 36 glycosyltransferase in Vibrio. Biochem J 377, 225–232 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam Y. W. et al. Crystal structure and substrate recognition of cellobionic acid phosphorylase, which plays a key role in oxidative cellulose degradation by microbes. J Biol Chem 290, 18281–18292 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidaka M. et al. Chitobiose phosphorylase from Vibrio proteolyticus, a member of glycosyl transferase family 36, has a clan GH-L-like (α/α)6 barrel fold. Structure 12, 937–947 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidaka M. et al. Structural dissection of the reaction mechanism of cellobiose phosphorylase. Biochem J 398, 37–43 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchrieser C. et al. Comparison of the genome sequences of Listeria monocytogenes and Listeria innocua: clues for evolution and pathogenicity. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 35, 207–213 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima M. et al. Functional and structural analysis of a β-glucosidase involved in β-1,2-glucan metabolism in Listeria innocua. PLoS One 11, e0148870 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnick T. A., Methé B. A. & Leschine S. B. Clostridium phytofermentans sp. nov., a cellulolytic mesophile from forest soil. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 52, 1155–1160 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krissinel E. & Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J Mol Biol 372, 774–797 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perić-Hassler L., Hansen H. S., Baron R. & Hünenberger P. H. Conformational properties of glucose-based disaccharides investigated using molecular dynamics simulations with local elevation umbrella sampling. Carbohydr Res 345, 1781–1801 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoorebeke A. et al. Crystallization and X-ray diffraction studies of cellobiose phosphorylase from Cellulomonas uda. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun 66, 346–351 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nidetzky B., Eis C. & Albert M. Role of non-covalent enzyme-substrate interactions in the reaction catalysed by cellobiose phosphorylase from Cellulomonas uda. Biochem J 351, 649–659 (2000). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasutake Y. et al. Structure of the monomeric isocitrate dehydrogenase: evidence of a protein monomerization by a domain duplication. Structure 10, 1637–1648 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sintchak M. D., Arjara G., Kellogg B. A., Stubbe J. & Drennan C. L. The crystal structure of class II ribonucleotide reductase reveals how an allosterically regulated monomer mimics a dimer. Nat Struct Biol 9, 293–300 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett M. J., Schlunegger M. P. & Eisenberg D. 3D domain swapping: a mechanism for oligomer assembly. Protein Sci 4, 2455–2468 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlunegger M. P., Bennett M. J. & Eisenberg D. Oligomer formation by 3D domain swapping: a model for protein assembly and misassembly. Adv Protein Chem 50, 61–122 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida T. et al. Crystal structure of glycoside hydrolase family 55 β-1,3-glucanase from the Basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium. J Biol Chem 284, 10100–10109 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung W. S. et al. Structural and functional insights into intramolecular fructosyl transfer by inulin fructotransferase. J Biol Chem 282, 8414–8423 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace C. N., Vajdos F., Fee L., Grimsley G. & Gray T. How to measure and predict the molar absorption coefficient of a protein. Protein Sci 4, 2411–2423 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michal G. d-Glucose-1-phosphate in Methods of enzymatic analysis 3rd edition (eds Bergmeyer H., Bergmeyer J. & Grassl M.) 185–191 (Verlag Chemie, 1984).

- Lowry O. H. & Lopez J. A. The determination of inorganic phosphate in the presence of labile phosphate esters. J Biol Chem 162, 421–428 (1946). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell H. R., Johnson O. & Leslie A. G. Autoindexing diffraction images with iMosflm. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 69, 1195–1203 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z. & Minor W. Processing of X-ray Diffraction Data Collected in Oscillation Mode. Method Enzymol 276, 307–326 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger T. C. et al. Decision-making in structure solution using Bayesian estimates of map quality: the PHENIX AutoSol wizard. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 65, 582–601 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagin A. & Teplyakov A. Molecular replacement with MOLREP. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66, 22–25 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P. & Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 60, 2126–2132 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A. & Dodson E. J. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 53, 240–255 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabata T. MATRAS: A program for protein 3D structure comparison. Nucleic Acids Res 31, 3367–3369 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert X. & Gouet P. Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res 42, W320–324 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.