Abstract

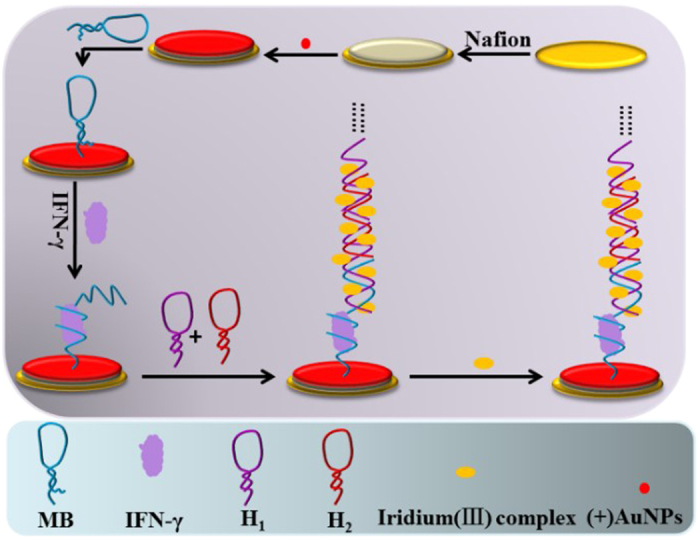

A novel iridium(III) complex was prepared and used as a conductor for sensitive and enzyme-free electrochemical detection of interferon gamma (IFN-γ). This assay is based on a dual signal amplification mechanism involving positively charged gold nanoparticles ((+)AuNPs) and hybridization chain reaction (HCR). To construct the sensor, nafion (Nf) and (+)AuNPs composite membrane was first immobilized onto the electrode surface. Subsequently, a loop-stem structured capture probe (CP) containing a special IFN-γ interact strand was modified onto the (+)AuNP surface via the formation of Au-S bonds. Upon addition of IFN-γ, the loop-stem structure of CP was opened, and the newly exposed “sticky” region of CP then hybridized with DNA hairpin-1 (H1), which in turn opened its hairpin structure for hybridizing with DNA hairpin-2 (H2). Happen of HCR between H1 and H2 thus generated a polymeric duplex DNA (dsDNA) chain. Meanwhile, the iridium(III) complex could interact with the grooves of the dsDNA polymer, producing a strong current signal that was proportional to IFN-γ concentration. Thus, sensitive detection of IFN-γ could be realized with a detection limit down to 16.3 fM. Moreover, satisfied results were achieved by using this method for the detection of IFN-γ in human serum samples.

Interferon gamma (IFN-γ) is a type of cytokine that can activate multiple signal transduction pathways through the transcriptional regulation of immunologically relevant genes1. IFN-γ is unrestricted by T-helper cells with stimulation by antigens, and is clinically employed to diagnose latent tuberculosis2. In addition, dysregulation of IFN-γ secretion is associated with various diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease, genital herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections and Alzheimer’s disease3. Thus, sensitive detection of IFN-γ can be used to investigate the vigor of the immune response as well as for the diagnosis of infectious diseases.

Electrochemical sensing platforms have been extensively used for the detection of biomolecules due of their intrinsic advantages, including good portability, low cost, high sensitivity and simple operation4. Recently, numerous electrochemical methods have been developed for IFN-γ detection coupled with a number of signal amplification-based on strategies1,5,6,7. For instance, Zhao et al. constructed an electrochemical aptasensor for IFN-γ sensing based on the hybridization chain reaction (HCR) coupled with enzyme-signal amplification8; Luo and Pu groups realized IFN-γ detection using a dual signal amplification approach by exonuclease-mediated surface-initiated enzymatic polymerization2; Wang and He groups developed a sensitive label-free electrochemical aptasensor for IFN-γ detection through nuclease cleavage-assisted target recycling amplification9. However, these methods have certain drawbacks, such as the use of enzymes and/or the labelling of probe molecules, which limit the utilization of them for the routine detection of IFN-γ. Thus, developing low-cost, enzyme-free, simple and sensitive strategies for IFN-γ detection continues to attract tremendous interest.

Iridium(III) complexes have been widely used coupled with electrochemiluminescent10,11,12 and fluorescent13,14,15,16,17 detection techniques due to their high luminescence efficiency, variable photophysical properties and different excited-state characteristics. In addition, such metal complexes can also efficiently intercalate into the grooves of dsDNA strands18. Recently, a number of electrochemiluminenscent sensors have been constructed for the sensitive sensing of protein19,20,21 and DNA22,23. However, to the best of our knowledge, no electrochemical platform has yet been developed by using the iridium(III) complex as an electron conductor for the detection of protein.

In this work, we synthetized an iridium(III) complex that possesses good conductivity, using it as an electron mediator, a sensitive and enzyme-free electrochemical sensor for the determination of IFN-γ based on HCR signal amplification was developed. To construct the sensor, Nf/AuNPs composite membrane was first immobilized onto the electrode surface. After that, a loop-stem structured capture probe (CP) containing a special IFN-γ interact strand was modified onto the (+)AuNP surface via the formation of S-Au bonds. Upon addition of IFN-γ, the loop-stem structure of CP was opened, and the newly exposed “sticky” region of CP then hybridized with H1 to open the hairpin structure of it, accompanied with the happen of HCR between H1 and H2 for the formation of dsDNA polymer. Subsequently, iridium(III) complex could bind with the grooves of the dsDNA polymer, producing a strong current signal that was proportional to IFN-γ concentration (Fig. 1). Thus, sensitive IFN-γ detection could be achieved based on identifying the current signal change of differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) signal. Compared to enzyme-assisted signal amplification, HCR avoids the use of enzymes, accordingly improved the robustness and stability of the sensor. Notably, the iridium(III) complex used here could interact in a stable fashion with the unlabelled dsDNA polymers, making the detection of IFN-γ simple and low-cost24,25.

Figure 1. Scheme of the electrochemical IFN-γ detection assay.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Gold(III) chloride trihydrate (HAuCl4·3H2O), sodium chloride (NaCl), sodium borohydride (NaBH4), bovine serum albumin (BSA), human serum albumin (HSA) and immunoglobulin G (IgG) were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Interferon gamma (IFN-γ) was purchased from Sino Biological Inc. (China). 20 mM of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.0) was utilized for all of the detection experiments. All other chemicals were analytical grade and utilized without extra purification. Oligonucleotides used in the assay were purchased from Techdragon Inc. (Hong Kong, China) and the DNA sequences of them were shown in Table S1.

Apparatus

All electrochemical measurements were performed on a CV-3 electrochemical workstation (CH Instruments, Inc. U.S.A.). A conventional three-electrode system including a modified gold electrode, a platinum wire counter electrode and an Ag/AgCl reference electrode was utilized in all of the experiments. Gel electrophoresis was carried out on a GT Mini-Gel system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Itally). Size of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) was detected by using high resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM, Tecnai G2 F20, USA). Nanosurface of the electrode was characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Hitachi 2000, Japan).

Synthesis of iridium(III) complex

The structure of the iridium(III) complex [Ir(ppy)2(phen-dione)]PF6 was shown in Figure S2a, and it was synthetized according to the literature method21. A suspension of [Ir(ppy)2]2Cl2 (0.2 mmol) and phen-dione (0.42 mmol) in a solvent solution of mixed CH2Cl2:MeOH (1:1, 20 mL) was refluxed overnight under the protection of N2. The reaction solution was then allowed to cool down to 25 °C, and filtered to remove solid dimer that was not reacted. An aqueous solution of NH4PF6 (excess) was added into the filtrate and the resulting solution was rotary evaporated until crude product was precipitated out. The precipitate was then filtered and washed with several portions of water (2 × 40 mL) followed by diethyl ether (2 × 40 mL). Afterwards, the product was recrystallized by acetone:diethyl ether vapor diffusion to yield the titled compound as a brown solid (Figure S1).

Preparation of (+)AuNPs

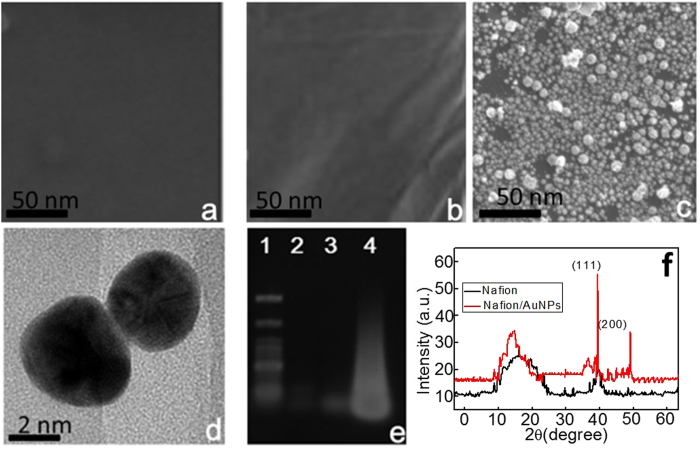

Positively charged gold nanoparticles ((+)AuNPs) were obtained through the reported method22 based on the reduction of 15 mL HAuCl4 (1.0 mM) by using 2 mL of NaBH4 (100 mM) in the presence of 2 mL cetyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB, 10 mM). The color of prepared (+)AuNPs was orange red and the average sizes of them estimated from high resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) analysis were about 4 nm (Fig. 2d).

Figure 2.

SEM images of bare gold electrode (a), Nf modified gold electrode (b) and (+)AuNPs/Nf modified electrode (c); HRTEM images of (+)AuNPs (d); Gel electrophoresis (lane 1: DNA marker, lane 2: 1.0 mM H1 + 1.0 mM H2, lane 3: 1.0 mM CP and lane 4: 1.0 mM H1 + 1.0 mM H2 + 1.0 mM CP (e); XRD patterns of Nf and Nf/AuNPs (f).

Fabrication of iridium(III) complex/{H2/H1}n/CP/(+)AuNPs/Nf modified gold electrode

The pretreat and modification of gold electrodes with Nf and (+)AuNPs were conducted according to the previous method28. After the immobilization of Nf and (+)AuNPs onto the surface electrodes, they were incubated in CP solution over night at room temperature (RT). Subsequently, the CP/(+)AuNPs/Nf modified electrodes were immersed in 6-mercapto-1-hexanol (MCH, 2.0 mM) for 1.5 h at RT to decrease the nonspecific DNA adsorption and to optimize the orientation of the aptamer. Then, the CP/(+)AuNPs/Nf modified electrodes were incubated in IFN-γ solution (1 h) to open the hairpin structure of CP for the following HCR between H1 and H2. At last, the {H2/H1}n/IFN-γ/CP/(+)AuNPs/Nf modified electrodes were immersed in PBS and CH3CN (8/2, v/v) buffer containing 20 μM of iridium(III) complex to realize the interaction of iridium(III) complex with dsDNA polymers.

Gel electrophoresis

Before conducting the gel electrophoresis, H1 and H2 samples were heated to 95 °C for 5 min and then allowed to cool down to 25 °C before using. 1.0 wt% agarose gel was prepared for DNA samples loading. After the addition of different DNA samples (4.0 μL, 1.0 μM), gel electrophoresis was performed by using 1.0 × TAE as running buffer at a constant potential of 78 V for 40 min. At last, the gels were photographed by using the gel image system after Stains-All staining by ethidium bromide (EB) solution for 15 min.

Electrochemical detection of IFN-γ

To construct the electrochemical IFN-γ detection, CP/(+)AuNPs/Nf modified gold electrodes were immersed into PBS (20 mM, pH 7.0) containing different concentration of IFN-γ for 60 min at 37 °C. Then, they were immersed into H1 and H2 solution (2.0 μM) for 50 min for the happen of HCR at RT. After that, the {H2/H1}n/IFN-γ/CP/(+)AuNPs/Nf modified gold electrodes were immersed into the solution that contained of iridium(III) complex for 90 min to realize the interaction between iridium(III) complex and dsDNA polymers. Finally, the electrochemical characteristics of the sensor were determined in 20 mM of PBS (pH 7.0) through differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) experiments from −0.2 to 0.2 V.

Results and Discussion

Characteristics of the modified electrodes

The establishment of (+)AuNPs on the electrode surface can greatly improve the amount of CP immobilization. Here, SEM images were used to monitor the formation of Nf/(+)AuNPs, and an obvious thin film of Nf appeared after 5 μL of 1.0 wt% Nf added onto the gold electrode surface (Fig. 2b) compared to that of the bare gold electrode (Fig. 2a). Then, after the adsorption of (+)AuNPs, a homogeneous nano-surface was observed (Fig. 2c). Moreover, Nf and Nf/AuNPs were investigated using X-ray diffraction (XRD) (Fig. 2f). The XRD pattern of Nf is consistent with cubic phase, referring to the standard spectra (JCPDS 15-0770), which displays two characteristic peaks occurring at 2θ of 17°, 39°. Then, two obvious characteristic peaks of AuNPs at 39.5° and 49° for 111 and 200 appeared after the formation of Nf/AuNPs, and a shift in the diffraction peak of Nf was observed due to its combination with AuNPs.

Gel electrophoresis of different DNA strands

After the addition of IFN-γ, HCR generated long-chain dsDNA polymers. Thus, gel electrophoresis was performed to verify the happen of HCR. As shown in Fig. 2e, HCR amplification between H1 and H2 triggered by CP resulted in an obvious high molecular-weight smeared band (lane 4) compared with that for the H1/H2 mixture (lane 2) and MB (lane 3), and this was consistent with our previous reports27.

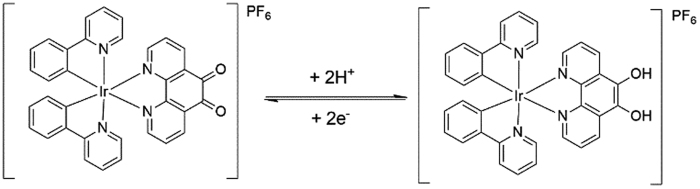

Conductivity of different iridium(III) complexes

To monitor the conductivity mechanism of the iridium(III) complex, different iridium(III) complexes were synthesized, and scanned in PBS buffer (pH 7.0). The results in Figure S3 showed that the iridium(III) complex used in our assay (a) has an good redox peak while that for others (b and c) exhibited no obvious peak current (curves b and c). The conductivity of the iridium(III) complex used in our assay could be attributed to the reversible oxidation-reduction reaction between the two ketonic groups and two oxhydryl groups involving the transfer of protons and electrons (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. The conductivity mechanism of iridium(III) complex used in our assay.

Characteristics of different electrodes

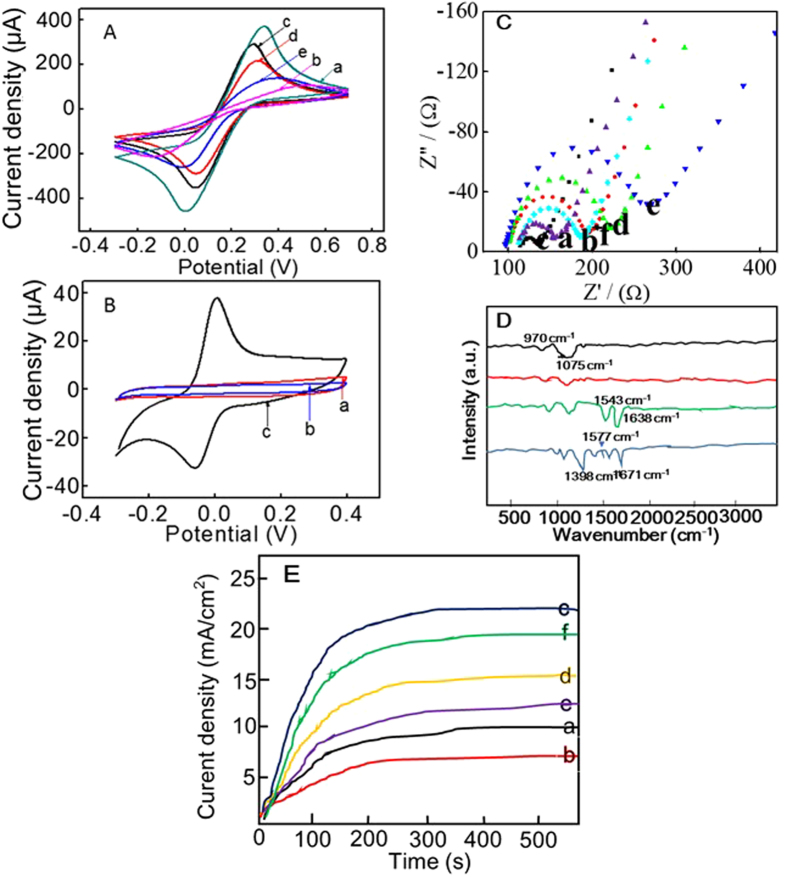

The modification process of the electrodes was characterized by using cyclic voltammetry (CV) experiments in the presence of 50 mM Fe(CN)63−/4−. As shown in Fig. 4A, a stable and well-defined redox peak was obtained for the bare gold electrode (curve a), and the peak current decreased greatly after the immobilization of Nf due to the character of it that can hinder electron transfer (curve b). Subsequently, an obvious increase of the peak current appeared after the adsorption of (+)AuNPs, because of the good electrical conductivity of (+)AuNPs (curve c). Then, the immobilization of CP onto (+)AuNPs surface based on Au-S bond greatly resulted in a decreased peak current (curve d). The reason for that mainly because MB is negatively charged, which can lead to the electrostatic repulsion with negatively charged [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− and hinder the electron transfer between the electrode and [Fe(CN)6]3−/4−. Moreover, after the happen of HCR between H1 and H2, the current response of [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− redox peak decreased further due to the increase of negatively-charged DNA strands (curve e). Meanwhile, CV experiments were also conducted in PBS solution to demonstrate the interaction of iridium(III) complex with dsDNA polymers. It could be seen from Fig. 4B that a well-fined redox peak appeared after the incubation of {H2/H1}n/IFN-γ/CP/(+)AuNPs/Nf modified gold electrodes with the iridium(III) complex (curve c), which could be attributed to the interaction of the iridium(III) complex with the grooves of the dsDNA polymers. On the contrary, no peaks appeared for the bare gold electrode (curve a) or {H2/H1}n/IFN-γ/CP/(+)AuNPs/Nf modified gold electrodes (curve b) in the absence of iridium(III) complexes, indicating the outstanding conductive capability of the iridium(III) complex.

Figure 4.

(A) CV experiments in Fe(CN)3−/4−: (a) bare electrode, (b) Nf, (c) AuNPs/Nf, (d) CP/AuNPs/Nf and (e) {H2/H1}n/IFN-γ/CP/AuNPs/Nf modified electrodes; (B) CV experiments in PBS: (a) bare electrode, (b) {H2/H1}n/IFN-γ/CP/AuNPs/Nf and (c) iridium(III) complex/{H2/H1}n/IFN-γ/CP/AuNPs/Nf modified electrodes; EIS (C) and chronoamperometric measurements (E) in Fe(CN)3−/4−: (a) bare electrode, (b) Nf, (c) AuNPs/Nf, (d) IFN-γ/CP/AuNPs/Nf and (e) {H2/H1}n/IFN-γ/CP/AuNPs/Nf modified electrodes; (D) FT-IR studies of Nf (a), Nf/AuNPs (b), IFN-γ/CP/AuNPs/Nf (c) and iridium(III) complex/{H2/H1}n/IFN-γ/CP/AuNPs/Nf (d).

In addition, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was also used to monitor the fabrication process of the modified electrodes. As shown in Fig. 4C, using 50 mM of Fe[(CN)6]3−/4− as the detection solution, a relatively small resistance was observed at the cleaned GCE (diagram a). Then, after the immobilization of the Nf membrane, the resistance gradually increased (diagram b), indicating that Nf inhibited the electron transfer between the solution and the base electrode. Subsequently, an obvious decrease of the resistance appeared after the adsorption of (+)AuNPs, because of the good electrical conductivity of (+)AuNPs (diagram c). However, after the immobilization of CP, IFN-γ, and the initiation of HCR between H1 and H2, the resistance increased gradually (diagrams d and e). The reason for the increased resistance is mainly due to the fact that the DNA strands are negatively charged, which directly led to electrostatic repulsion with the negatively charged [Fe(CN)6]3−/4−, hindering the electron transfer between the electrode and [Fe(CN)6]3−/4−. Finally, after the interaction of the iridium(III) complex with dsDNA polymers, the resistance decreased significantly, indicating that the iridium(III) complex has an outstanding conductive capability (diagram f). Meanwhile, chronoamperometric measurements that constructed in 50 mM of [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− at a constant potential of –0.3 V further illustrated the modification process of the electrodes. It could be seen from Fig. 4E that a stable current appeared within 200 s, and a corresponding current change was obtained with the stepwise-modification of the electrode, which was consistent with the EIS results.

Fourier transform-infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) is a useful tool for characterizing the characteristics of different materials. As shown in Fig. 4D, characteristic IR peaks of Nf appeared around 970 cm−1 (–COC– linkages), 1075 cm−1 (–SO3 H) and 1156 cm−1 (–CF2–) (curve a)29. After the adsorption of AuNPs, an obvious shift of the IR peaks of Nf could be found, indicating the effective adsorption of AuNPs onto the Nf membrane (curve b). Then, two obvious IR peaks appeared around 1543 cm−1 (amide II band, C–N stretch coupled with N–H bend) and 1638 cm−1 (amide I band, mainly C=O stretch), which displayed the FT-IR spectra of IFN-γ protein (curve “a”) after the immobilization of CP and IFN-γ onto the electrode surface (curve c)30. After that, the interaction of the iridium(III) complex directly induced a shift of the peak for the C=O bond, and new peaks of C=C at 1577 cm–1 and C-N at 1398 cm–1 confirmed the successful interaction of the iridium(III) complex with the dsDNA polymers31,32.

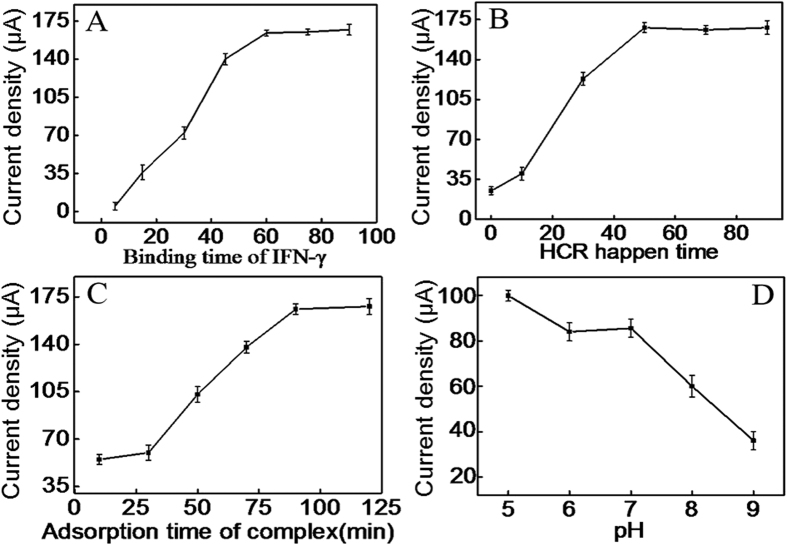

Optimization of the experimental conditions

The electrochemical signal of the iridium(III) complex mainly based on the amount of it that interacted into the grooves of dsDNA polymers. Thus, the specific bind of IFN-γ with CP can directly affect the happen of HCR, and accordingly affect the interaction of iridium(III) complex. As shown in Fig. 5A, the oxidation peak current of iridium(III) complex enhanced with the increase of the binding time between IFN-γ and CP in the range from 5 to 60 min and then reached a plateau, indicating 60 min could realize the effective binding of CP with IFN-γ. Thus, 60 min was selected as the optimum binding time between IFN-γ and CP.

Figure 5.

Effect of binding time of IFN-γ (A), the HCR time (B), the interaction time of iridium(III) complex with dsDNA polymers (C) and pH of the buffer (D).

In addition, the hybridization time between CP and H1/H2 mixture directly affected the happen of HCR. As displayed in Fig. 5B, the electrochemical signal of iridium(III) complex enhanced with increasing hybridization time of them in the range of 0–50 min. Such result indicated that HCR could effectively happen within 50 min. Therefore, 50 min was chosen as the optimum hybridization time.

The interaction time of iridium(III) complex into the grooves of dsDNA polymers was another crucial parameter that could influence the sensitivity of the detection assay. As displayed in Fig. 5C, the current signal was proportional to the interaction time of iridium(III) complex over the range from 5 to 90 min and then reached a plateau. So 90 min was used for the interaction of iridium(III) complex with dsDNA polymers.

The pH of the PBS also has an effect on the electrochemical behavior of the sensor because the activity of IFN-γ and the oxidation-reduction of iridium(III) complex may be affected by the acidity of the solution33. Just as shown in Fig. 5D, the peak current of iridium(III) complex decreased along with the increasing pH value from 5.0 to 9.0 and a plateau from 6.0 to 7.0. Considering that high acid solution may affect the activity of the protein, pH 7.0 was selected as the optimum pH of PBS.

Sensitivity of the assay

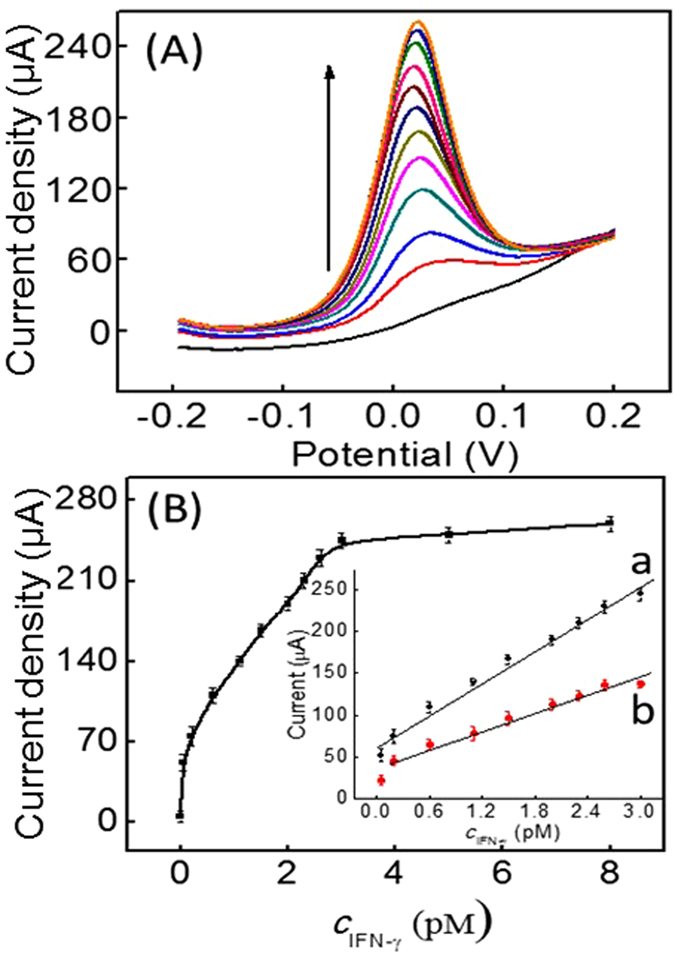

Under optimal conditions, IFN-γ detection could be realized based on monitoring the current signal change. As shown in Fig. 6A, the DPV peak currents of the iridium(III) complex increased along with the increase of IFN-γ concentration, and a linear range from 50 fM to 3.0 pM was obtained for IFN-γ detection (Fig. 6B, linear a), with a detection limit of 16.3 fM (3σ/slope). The linear regression equation was I = 63.35 + 63.58c (c: pM, R2 = 0.9971). The detection limit of the proposed method was lower than the reported aptamer-based IFN-γ detection methods (Table S2)5,8,9,34,35,36. Such high sensitivity mainly attributed to the dual signal amplification of HCR and (+)AuNPs. Meantime, we compared the performance of this sensor with a similar sensor {H2/H1}n/IFN-γ/CP that lacked (+)AuNPs. A linear relationship between peak current and IFN-γ concentration was obtained in the range of 200 fM–2.5 pM (Fig. 6B, linear b), illustrating the function of the (+)AuNPs as an electron mediator and signal amplifier.

Figure 6.

(A) DPV experiments for IFN-γ detection in 20 mM of PBS (pH 7.0); (B) Dose-response curve and calibration curve (inset) for IFN-γ detection (curve a: the proposed sensor and curve b: the sensor with {H2/H1}n/IFN-γ/CP modification).

Selectivity and stability of the sensor

The selectivity of the sensor was investigated by monitoring the current response of the sensor to IFN-γ, bovine serum albumin (BSA), immunoglobulin G (IgG) and human serum albumin (HSA). As shown in Figure S4, the current signal of iridium(III) complex for 1.5 pM of IFN-γ was greater than 15 pM of various other substances. These results obviously illustrated the high selectivity of the sensor for IFN-γ detection, which was mainly due to the high specificity of CP to IFN-γ. In addition, the stability of the sensor was studied by storing the sensor at room temperature for 10 days, and the sensor kept 95.2% of its initial response, which indicated that the sensor has a good life time for IFN-γ detection.

IFN-γ detection in human serum samples

Moreover, the application of the sensor for IFN-γ determination in serum samples was evaluated in a detection system containing 5.0% (v/v) human serum. As shown in Table S3, a good recovery in the range of 96.6–108.1% was obtained for IFN-γ detection with a relative standard deviation (RSD) between 1.87% and 4.06%, indicating the potential application of the assay for quantitative detection of IFN-γ in complex human samples.

Conclusion

In conclusion, an enzyme-free and highly sensitive electrochemical sensor for IFN-γ detection was developed by utilizing a novel iridium(III) complex as conductor coupled with a dual signal amplification mechanism involving HCR and (+)AuNPs. Importantly, this amplification mechanism avoids the use of enzymes. Moreover, the iridium(III) complex used here could interact stably with formed dsDNA polymers without modification, making the IFN-γ detection assay simple and low-cost. Finally, the assay was highly selective for IFN-γ due to the specificity of CP for IFN-γ, and could also function in diluted human serum. Thus, this approach could possibly be applied for developing biosensors to monitor IFN-γ levels associated with various human diseases.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Miao, X. et al. A cyclometalated iridium(III) complex used as a conductor for the electrochemical sensing of IFN-γ. Sci. Rep. 7, 42740; doi: 10.1038/srep42740 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by Hong Kong Baptist University (FRG2/15-16/002), the Health and Medical Research Fund (HMRF/14130522), the Research Grants Council (HKBU/12301115, HKBU/204612 and HKBU/201913), the French Agence Nationale de la Recherche/Research Grants Council Joint Research Scheme (AHKBU201/12; Oligoswitch ANR-12-IS07-0001), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21575121), the Guangdong Province Natural Science Foundation (2015A030313816), the Hong Kong Baptist University Century Club Sponsorship Scheme 2016, the Interdisciplinary Research Matching Scheme (RC-IRMS/15-16/03), the Science and Technology Development Fund, Macao SAR (098/2014/A2), and the University of Macau (MYRG2015-00137-ICMS-QRCM, MYRG2016-00151-ICMS-QRCM and MRG044/LCH/2015/ICMS), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (21628502).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions X.M.M. and Z.B.L. carried out the experiments, performed the data analysis. X.M.M. wrote the manuscript. C.-N.K., K.V. and G.-J.Y. performed the data analysis. C.-H.L. and D.-L.M. designed the experiments and analyzed the results.

References

- Chen Y., Pui T. S., Kongsuphol P., Tang K. C. & Arya S. K. Aptamer-based array electrodes for quantitative interferon-γ detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 53, 257–262 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C. et al. An electrochemical aptasensor for detection of IFN-γ using graphene and a dual signal amplification strategy based on the exonuclease-mediated surface-initiated enzymatic polymerization. Analyst 140, 7784–7791 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafa H. et al. Involvement of interferon-γ in bowel disease pathogenesis by nitric oxide pathway: a study in algerian patients. J. Interf. Cytok. Res. 30, 691–697 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao X. et al. Application of iridium(III) complex in label-free and non-enzymatic electrochemical detection of hydrogen peroxide based on a novel “on-off-on” switch platform. Sci. Rep. 6, 25774–25781 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farid S. et al. Detection of Interferon gamma using graphene and aptamer based FET-like electrochemical biosensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 71, 294–299 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Kwa T. & Revzin A. Simultaneous detection of cell-secreted TNF-α and IFN-γ using micropatterned aptamer-modified electrodes. Biomaterials 33, 7347–7355 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Mazurek G. H. & Alocilja E. C. Measurement of Interferon Gamma Concentration Using an Electrochemical Immunosensor. J. Electrochem. Soc. 163, B140–B145 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J., Chen C., Zhang L., Jiang J. & Yu R. An electrochemical aptasensor based on hybridization chain reaction with enzyme-signal amplification for interferon-gamma detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 36, 129–134 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan G. et al. A highly sensitive label-free electrochemical aptasensor for interferon-gamma detection based on graphene controlled assembly and nuclease cleavage-assisted target recycling amplification. Biosens. Bioelectron. 44, 57–63 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y., Huang Y., Lei J., Zhang L. & Ju H. Design and biosensing of Mg2+-dependent DNAzyme-triggered ratiometric electrochemiluminescence. Anal. Chem. 86, 5158–5163 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Yuan Y., Zhuo Y., Chai Y. & Yuan R. Self-Enhanced Electrochemiluminescence Nanorods of Tris (bipyridine) Ruthenium (II) Derivative and Its Sensing Application for detection of N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase. Anal. Chem. 88, 2258–2265 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Zhuo Y., Liao N., Chai Y. & Yuan R. Ultrasensitive electrochemiluminescent detection of cardiac troponin I based on a self-enhanced Ru (II) complex. Talanta 129, 219–226 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He H.-Z. et al. Label-free luminescence switch-on detection of T4 polynucleotide kinase activity using a G-quadruplex-selective probe. Chem. Commun. 50, 5313–5315 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S. et al. Luminescence switch-on detection of protein tyrosine kinase-7 using a G-quadruplex-selective probe. Chem. Sci. 6, 4284–4290 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. et al. An ultrasensitive biosensor for DNA detection based on hybridization chain reaction coupled with the efficient quenching of a ruthenium complex to CdTe quantum dots. Chem. Commun. 49, 7424–7426 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L. et al. A luminescence switch-on probe for terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) activity detection by using an iridium (III)-based i-motif probe. Chem. Commun. 51, 9953–9956 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung K. H. et al. Label-free luminescence switch-on detection of hepatitis C virus NS3 helicase activity using a G-quadruplex-selective probe. Chem. Sci. 6, 2166–2171 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma D. L. et al. A luminescent cocaine detection platform using a split G-Quadruplex-selective iridium(III) complex and a three-Way DNA junction architecture. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 19060–19067 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agnihotri N., Chowdhury A. D. & De A. Non-enzymatic electrochemical detection of cholesterol using β-cyclodextrin functionalized graphene. Biosens. Bioelectron. 63, 212–217 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Dong Y., Li J. & Yuan R. A ferrocene-switched electrochemiluminescence “off–on” strategy for the sensitive detection of cardiac troponin I based on target transduction and a DNA walking machine. Chem. Commun. 51, 14369–14372 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M., Chen Y., Xiang Y., Yuan R. & Chai Y. Target-induced structure switching of DNA for label-free and ultrasensitive electrochemiluminescent detection of proteins. Chem. Commun. 50, 3211–3213 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. et al. In situ hybridization chain reaction amplification for universal and highly sensitive electrochemiluminescent detection of DNA. Anal. Chem. 84, 7750–7755 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gui G. et al. Supersandwich-type electrochemiluminescenct aptasensor based on Ru (phen) 3 2+ functionalized hollow gold nanoparticles as signal-amplifying tags. Biosens. Bioelectron. 47, 524–529 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L. H. et al. Label-Free luminescent switch-on probe for ochratoxin a detection using a G-quadruplex-selective iridium(III) complex. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 8313–8318 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M. et al. Label-free luminescent detection of LMP1 gene deletion using an intermolecular G-quadruplex-based switch-on probe. Biosens. Bioelectron. 70, 338–344 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Z. et al. An Ir(III) complex chemosensor for the detection of thiols. Sci. Tech. Adv. Mater. 17, 109–114, doi: 10.1080/14686996.2016.1162081 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Miao X., Xing K., Zhu A. & Ling L. Enhanced electrochemical recognition of double-stranded DNA by using hybridization chain reaction and positively charged gold nanoparticles. Biosens. Bioelectron. 74, 687–690 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao X. et al. Ultrasensitive electrochemical detection of protein tyrosine kinase-7 by gold nanoparticles and methylene blue assisted signal amplification. Biosens. Bioelectron. 83, 39–44 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. et al. Magnetic graphene nanosheet-based microfluidic device for homogeneous real-time electronic monitoring of pyrophosphatase activity using enzymatic hydrolysate-induced release of copper ion. Anal. Chem. 88, 1030–103(2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth A. et al. Infrared spectroscopy of proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 1767, 1073–1101 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng K. et al. Sulfonated graphene oxide–silica for highly selective Nafion-based proton exchange membranes. J. Mater. Chem. A 2, 16083–16092 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Feng K. et al. “Evaporating” graphene oxide sheets (GOSs) for rolled up GOSs and its applications in proton exchange membrane fuel cell. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 5, 1481–1488 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S. et al. Luminescence switch-on assay of interferon-gamma using a G-quadruplex-selective iridium(iii) complex. Chem. Commun. 51, 16033–16036 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao X. et al. Ultrasensitive electrochemical detection of miRNA-21 by using an iridium(III) complex as catalyst. Biosens. Bioelectron. 86, 454–458 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. et al. Amplified surface plasmon resonance immunosensor for interferon-Gamma based on a streptavidin-incorporated aptamer. Biosens. Bioelectron. 37, 68–74 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C. et al. An electrochemical aptasensor detection of IFN-γ using graphene and a dual signal amplification strategy based on the exonuclease-mediated surface-initiated enzymatic polymerization. Analyst 140, 7784–7791 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.