ABSTRACT

In previous studies, we identified the fatty acid kinase virulence factor regulator B (VfrB) as a potent regulator of α-hemolysin and other virulence factors in Staphylococcus aureus. In this study, we demonstrated that VfrB is a positive activator of the SaeRS two-component regulatory system. Analysis of vfrB, saeR, and saeS mutant strains revealed that VfrB functions in the same pathway as SaeRS. At the transcriptional level, the promoter activities of SaeRS class I (coa) and class II (hla) target genes were downregulated during the exponential growth phase in the vfrB mutant, compared to the wild-type strain. In addition, saePQRS expression was decreased in the vfrB mutant strain, demonstrating a need for this protein in the autoregulation of SaeRS. The requirement for VfrB-mediated activation was circumvented when SaeS was constitutively active due to an SaeS (L18P) substitution. Furthermore, activation of SaeS via human neutrophil peptide 1 (HNP-1) overcame the dependence on VfrB for transcription from class I Sae promoters. Consistent with the role of VfrB in fatty acid metabolism, hla expression was decreased in the vfrB mutant with the addition of exogenous myristic acid. Lastly, we determined that aspartic acid residues D38 and D40, which are predicted to be key to VfrB enzymatic activity, were required for VfrB-mediated α-hemolysin production. Collectively, this study implicates VfrB as a novel accessory protein needed for the activation of SaeRS in S. aureus.

IMPORTANCE The SaeRS two-component system is a key regulator of virulence determinant production in Staphylococcus aureus. Although the regulon of this two-component system is well characterized, the activation mechanisms, including the specific signaling molecules, remain elusive. Elucidating the complex regulatory circuit of SaeRS regulation is important for understanding how the system contributes to disease causation by this pathogen. To this end, we have identified the fatty acid kinase VfrB as a positive regulatory modulator of SaeRS-mediated transcription of virulence factors in S. aureus. In addition to describing a new regulatory aspect of SaeRS, this study establishes a link between fatty acid kinase activity and virulence factor regulation.

KEYWORDS: VfrB, SaeRS, two-component system, regulation, fatty acid kinase

INTRODUCTION

Staphylococcus aureus is a potent human pathogen because of its ability to cause a wide variety of diseases, ranging from localized skin and soft tissue infections to widespread organ destruction and sepsis (1–5). Its ability to cause a variety of diseases is due in part to its numerous virulence factors, including secreted toxins and proteases. Moreover, S. aureus is able to regulate these virulence factors in order to express them during opportune times of infection. Like many bacteria, S. aureus utilizes a variety of sensing and regulatory networks, including 16 two-component regulatory systems (TCSs), to fine tune virulence factor production (6).

SaeRS, one of the TCSs encoded by S. aureus, has been shown to regulate over 200 genes, including numerous virulence factors such as protein A, α- and β-hemolysins, coagulase, secreted proteases, and enzymes necessary for capsule production or biofilm formation (7–11). Classically, two-component systems are composed of a sensor histidine kinase, which recognizes a stimulatory signal, and a cognate response regulator, which coordinates gene expression either positively or negatively. In the SaeRS system, the sensor histidine kinase (SaeS) becomes autophosphorylated at a conserved histidine residue upon the sensing of a stimulus and subsequently relays this phosphoryl group to the response regulator (SaeR) (12, 13). Phosphorylated SaeR is then able to interact with defined promoter elements to modulate gene transcription either positively or negatively (14). Compared with the canonical two-component system, the Sae system contains two additional proteins, i.e., the lipoprotein SaeP and the membrane protein SaeQ, which modulate its activity (15, 16). Specifically, these proteins together form a complex to activate the phosphatase activity of SaeS, thereby deactivating the SaeRS system.

The four proteins that constitute SaePQRS are cotranscribed from two separate promoters, P1 and P3 (16–18). The P3 promoter, which is located within the saeQ open reading frame, drives constitutive basal transcription of saeR and saeS (15, 17). Similar to transcriptional regulation of other two-component systems, expression of the SaeRS system is autoregulated from the P1 promoter; upon activation, SaeR binds the promoter and increases transcription of all four genes in the operon (17). Under standard in vitro growth conditions, expression and activation of the system are greatest during the postexponential growth phase (8, 18, 19). The exact signaling molecule for SaeS kinase activation is unknown, as it is for many sensor kinases, but this system does respond to multiple stimuli, such as exposure to hydrogen peroxide, antibiotics, α-defensins, human polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs), and host calprotectin (12, 17, 20–22). The most studied of these activators is human neutrophil peptide 1 (HNP-1), and addition of this stimulus induces transcription from the P1 promoter (15–17). This type of activation of the SaeRS system has been reported to be required for most studied S. aureus strains. However, S. aureus strain Newman has a single amino acid substitution in the transmembrane domain of SaeS (L18 to P18) that renders SaeS constitutively active (18, 23).

The activation of SaeRS in response to an environmental cue leads to a modulation in gene expression of numerous virulence determinants (24). The SaeRS regulon is composed of genes transcribed from two classes of promoters, previously termed class I and class II on the basis of their affinity for SaeR-mediated activation (25). Class I promoters possess low affinity for SaeR, as they have two SaeR-binding sites, and include the sae P1 promoter (14), as well as the coa, fnbA, eap, sib, and efb promoters (23). In contrast, class II target genes (hla, hlb, and cap) are expressed even in the absence of high levels of phosphorylated SaeR, and the promoters possess a single SaeR-binding site. Therefore, under nonstimulatory standard conditions, class II genes are transcribed in the presence of low levels of SaeRS activation (SaeR phosphorylation). Conversely, the expression of class I genes is achieved when the SaeRS system is activated (i.e., high levels of phosphorylated SaeR).

Previously, our group identified virulence factor regulator B (VfrB) (also called FakA) as a novel regulator of virulence determinant expression, including that of the hla-encoded protein α-hemolysin and secreted proteases (26). Subsequent studies revealed that VfrB is a component of a novel fatty acid kinase complex that cells use to incorporate exogenous fatty acids into the bacterial membrane (27). Furthermore, microarray studies revealed that, in addition to hla, the expression of several other SaeRS-controlled genes was downregulated in vfrB mutants, consistent with altered SaeRS activity. Here we demonstrate that virulence factor regulation in response to VfrB is SaeRS dependent and that VfrB is an important contributor to the activation of SaeRS.

RESULTS

SaeRS activity is positively modulated by VfrB.

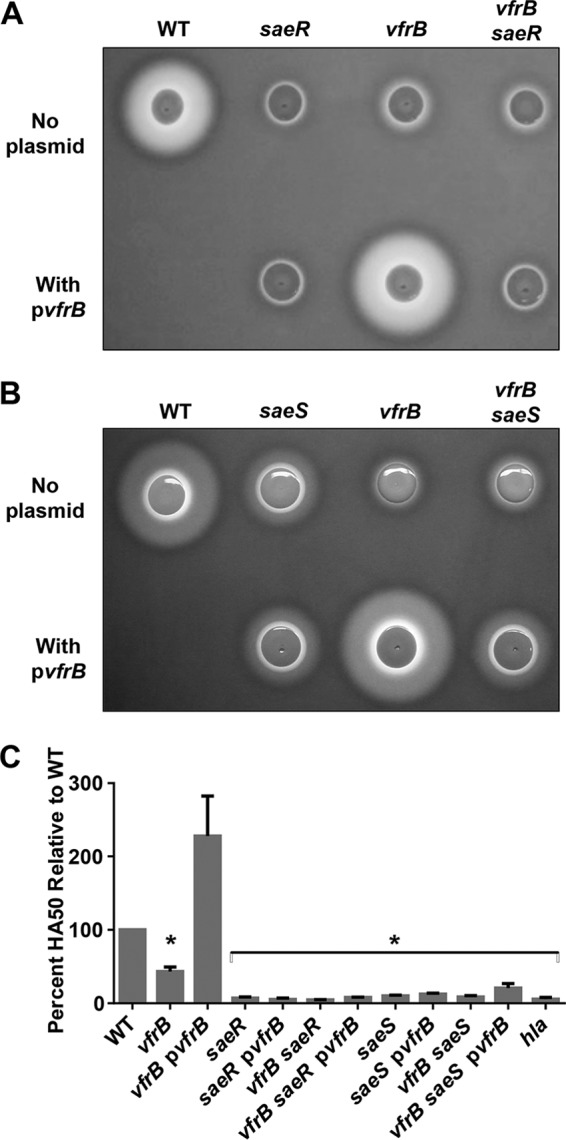

Our group previously demonstrated that virulence factor production in a vfrB mutant is altered from that of the wild-type strain (26). Similar to saeRS mutants (28), vfrB mutants show a marked reduction in Hla-dependent hemolytic activity when grown on rabbit blood agar, demonstrating decreased ability to produce Hla, and have enhanced production of V8 protease (26). Hla is under the control of multiple transcriptional and posttranscriptional factors (29–34). Since Sae is known to be a major contributor to hla expression, we sought to determine whether changes in Hla activity in response to VfrB are in the same pathway as SaeRS or in independent pathways. To this end, we analyzed the effects of a vfrB deletion in saeR and saeS mutants on hemolysis profiles. As shown in Fig. 1A, the vfrB mutant displayed an absence of α-hemolysin activity similar to that of an saeR mutant, demonstrating only the small zone of Hla-independent hemolysis that we observed previously (26). Furthermore, complementation with vfrB did not restore the α-hemolysin activity of the saeR mutant, demonstrating the need for SaeR for VfrB-dependent activation of Hla production. Similarly, complementation of the saeR vfrB double mutant strain with vfrB did not restore α-hemolysin activity, again indicating that the SaeRS two-component system is required to mediate this hemolysis.

FIG 1.

VfrB-dependent Hla activity requires SaeRS. The hemolytic activity of wild-type (WT), saeR mutant, vfrB mutant, and vfrB saeR double mutant strains (A) or wild-type, saeS mutant, vfrB mutant, and vfrB saeS double mutant strains (B) on TSA containing 5% rabbit blood or the activity of culture supernatants in whole rabbit blood (C) is shown. pvfrB indicates the presence of vfrB expressed from a plasmid. Error bars, standard errors of the mean (SEMs) (n = 3). *, P < 0.05, relative to the wild-type strain, using Student's t test. Images and the 50% hemolytic activity (HA50) analysis are representative of ≥3 replicate experiments.

It is possible that VfrB alters SaeR activity independent of SaeS; therefore, a mutant lacking saeS was also examined. As observed for the saeR mutant, the saeS mutant was less hemolytic, similar to the vfrB mutant (Fig. 1B). Moreover, complementation with vfrB did not restore the α-hemolysin activity of the saeS mutant, demonstrating the need for SaeS for VfrB activation of Hla production. The hemolysis of a vfrB saeS double mutant strain was even more decreased than that of the saeS mutant strain, resembling that of a vfrB mutant strain. Similarly, when vfrB was provided on a plasmid in the vfrB saeS double mutant strain, hemolytic activity was only partially restored, resembling that of the saeS single mutant strain. In parallel with these plate-based hemolysis assays, we also performed a quantitative hemolysis assay. Consistent with our previous studies (26), there was less hemolysin activity in supernatants from the vfrB mutant and, as expected, there was an absence of hemolysin activity in the mutants lacking sae when they were grown in broth (Fig. 1C). Taken together, these results demonstrate that VfrB alone does not mediate the expression of Hla but asserts its effects in the same pathway as SaeRS, most likely by exerting a stimulatory effect on the SaeRS system.

VfrB mediates expression of SaeRS-dependent genes.

After determining that VfrB requires SaeRS to activate Hla production, we sought to examine more carefully whether VfrB controls the activation of SaeRS-dependent promoters. In order to determine whether the expression of SaeRS-controlled genes is mediated by VfrB, we analyzed transcription profiles of well-characterized class I and class II target genes. A Pcoa-lacZ reporter fusion construct and a Phla-lacZ reporter fusion construct were generated in both wild-type and vfrB mutant strains, to analyze class I and class II promoter activities, respectively. In order to first determine whether these newly generated Pcoa-lacZ and Phla-lacZ reporter fusions accurately represented transcription from the promoters, β-galactosidase activity was measured in wild-type strains over time (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). As described previously, coa transcriptional activity was maximal during the exponential growth phase (35). Similarly, hla promoter activity was maximal during the stationary growth phase, as documented previously (8, 18, 19), demonstrating that both reporter constructs accurately reflected previously published studies of these promoters. β-Galactosidase activity measured in the wild-type strain harboring an empty vector (pJB185) revealed that the activity level was less than 1 Miller unit (data not shown). Next, promoter activities of coa and hla in vfrB mutant strains were compared to those of the wild-type strain during both late exponential growth phase and stationary growth phase, when SaeRS expression and activity are maximal. In negative-control experiments, the promoter activities of both coa and hla were also measured in a saeR mutant strain, as expression from these promoters should be minimal. Experiments performed with cultures grown to late exponential phase (5 h) revealed that the transcriptional activity of coa was 7.3-fold decreased in vfrB mutants, compared to the wild-type strain (Fig. 2A). During stationary growth phase (8 h), the promoter activity of coa was again lower (5.3-fold) in the vfrB mutant than in the wild-type strain (Fig. 2B).

FIG 2.

Expression of SaeRS-controlled genes is mediated by VfrB. The β-galactosidase activity (in modified Miller units) from either Pcoa-lacZ (A and B) or Phla-lacZ (C and D) transcriptional fusions was measured at 5 h (A and C) and 8 h (B and D) for wild-type (WT), vfrB mutant, and saeR mutant strains in TSB. Error bars, SEMs (n = 3). *, P < 0.05, relative to the wild-type strain, using Student's t test. Data are representative of ≥3 individual experiments.

Class II promoters would be expected to be less affected by alterations in SaeRS activity, and analysis of hla promoter activity in late exponential growth phase revealed a modest decrease (2.2-fold) in the vfrB mutant strain, compared to the wild-type strain (Fig. 2C). However, there was no significant difference in hla transcriptional activities in stationary growth phase when wild-type and mutant expression levels were compared (Fig. 2D), mimicking findings observed previously, using quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR), for hla expression in a vfrB mutant (26). As expected for both coa and hla, transcriptional activities were at basal levels in saeR mutants for both growth phases that were analyzed. The decreased fold changes for hla promoter activity, compared with coa promoter activity, between wild-type and vfrB mutant strains suggest that VfrB-mediated activation has a greater role in the modulation of class I target genes. This is not unexpected, since these are the targets most sensitive to SaeR phosphorylation. Collectively, these results demonstrate that VfrB is necessary to activate expression from both class I and class II SaeRS-controlled promoters but it exerts a greater effect on class I promoters.

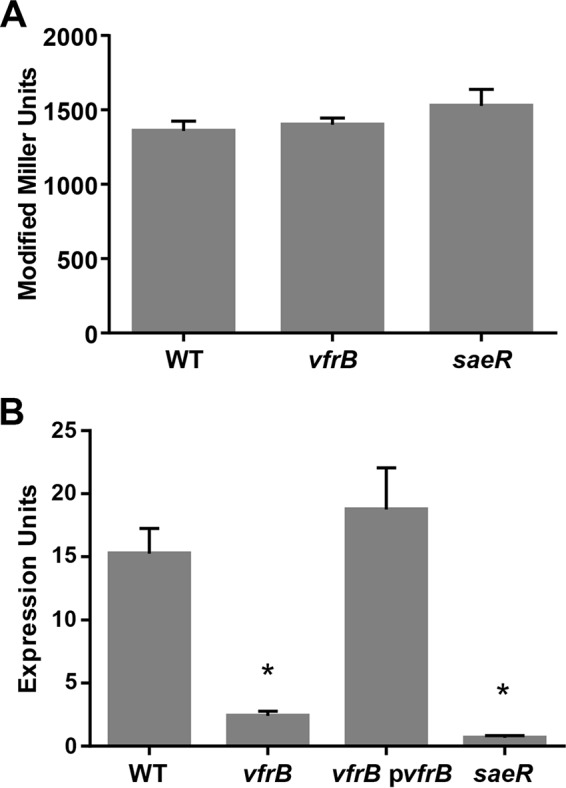

VfrB positively regulates transcription of saePQRS.

One possible mechanism by which VfrB controls SaeRS-mediated transcription is by regulating gene expression from the P1 or P3 promoters of the saePQRS operon. We first sought to determine whether VfrB modulates basal levels of saeRS expression through changes in sae P3 promoter activity; this was performed by analyzing activity from the P3 promoter using a PsaeP3-lacZ reporter fusion in wild-type, vfrB, and saeR mutant strains (Fig. 3A). We found no difference in promoter activity among the three strains, indicating that VfrB does not modulate the basal expression of saeRS from the P3 promoter. This finding also rules out the lack of expression of SaeRS from the P3 promoter as an explanation for reduced target gene expression. One consequence of VfrB altering class I sae promoter activity is that the P1 promoter (driving saePQRS expression) itself would be expected to be uninduced in a vfrB mutant, essentially shutting off the positive feedback loop of Sae regulation. In order to test this hypothesis, we performed qRT-PCR studies to analyze the saeP transcript levels in wild-type, vfrB mutant, vfrB complement, and saeR mutant (negative-control) strains. In support of VfrB having an effect on SaeRS class I promoters, saeP expression was determined to be 6.3-fold lower in the vfrB mutant strain than in the wild-type strain (Fig. 3B). Additionally, sae expression was negligible in the saeR mutant strain. Finally, in order to determine whether SaeR expression had any effect on the transcription of vfrB, we analyzed vfrB transcript levels in a saeR mutant and found no significant difference in expression between the wild-type and mutant strains (data not shown). The observation that VfrB does not alter basal saeRS expression but affects promoters requiring SaeS stimulation (Pcoa and PsaeP1) suggests that VfrB modulates the activation state of the two-component system.

FIG 3.

saePQRS expression is controlled by VfrB. The β-galactosidase activity (in modified Miller units) from the PsaeP3-lacZ transcriptional fusion was measured at 5 h in TSB for wild-type (WT), vfrB mutant, and saeR mutant strains (A), and saeP transcript levels were analyzed in wild-type, vfrB mutant, vfrB complement (vfrB pvfrB), and saeR mutant strains grown for 5 h (B). Error bars, SEMs (n = 3). *, P < 0.05, relative to the wild-type strain, using Student's t test. Data are representative of ≥3 individual experiments.

Constitutively active SaeS bypasses the need for VfrB activation.

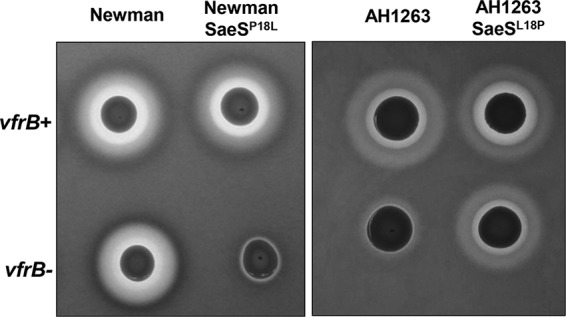

It was demonstrated previously that deletion of vfrB in multiple S. aureus strains led to dramatic reductions in Hla activity on rabbit blood agar (26). However, further analysis revealed that inactivation of vfrB in S. aureus Newman did not reduce Hla activity (Fig. 4), suggesting that the Newman strain bypasses the need for VfrB to regulate Hla expression. Interestingly, the Newman strain encodes a naturally occurring SaeS (L18P) substitution, whereby the system does not require a stimulus in order to mediate expression of SaeR-dependent genes (23). Therefore, we sought to determine whether the constitutively active nature of SaeS was responsible for bypassing the requirement for VfrB in Hla production. To this end, we introduced the vfrB mutation into the Newman strain, which was engineered to have the nonconstitutive SaeSP18L allele (18); hemolysis in this strain then became VfrB dependent. We then determined that this dispensability for VfrB for hla production in the constitutively active Newman strain occurred at the transcriptional level. When the hla promoter activity in the Newman wild-type strain was compared to that in the vfrB mutant in broth-grown cultures, there was no difference in activity (Fig. S2A and B). However, the same analysis comparing the Newman SaeSP18L and isogenic vfrB mutant strains showed restoration of VfrB dependence for full transcription of hla (Fig. S2A and B), confirming that, when the SaeS of the Newman strain was rendered nonconstitutively active, VfrB was no longer dispensable for hla expression. A similar pattern was expected and was observed for Pcoa. Specifically, the transcriptional activity of the coa promoter in the Newman vfrB mutant strain was 1.9-fold (5 h) and 2.0-fold (8 h) decreased, compared to the Newman wild-type strain (Fig. S2C and D). However, the coa promoter activity was 6.2-fold (5 h) and 6.0-fold (8 h) higher in the Newman SaeSP18L strain than in the isogenic vfrB mutant (Fig. S2C and D). Taken together, these results demonstrate that the ability of the Newman strain to bypass the need for VfrB for Hla production is due to constitutively active SaeS and not some other strain-dependent difference. Moreover, recapitulating the L18P substitution of the Newman strain in our USA300 strain (AH1263) was sufficient to allow Hla production in the absence of VfrB (Fig. 4), further demonstrating that an SaeRS system not requiring activation bypasses the necessity of VfrB. Collectively, these results demonstrate that VfrB is a positive activator of the SaeRS system in the absence of other activating mechanisms.

FIG 4.

VfrB is required for hemolysis unless SaeS is constitutively active. The hemolytic activity of Newman wild-type (WT), Newman SaeSP18L mutant, AH1263 wild-type, and AH1263 SaeSL18P mutant strains with vfrB (vfrB+) or without vfrB (vfrB−) was assessed on TSA containing 5% rabbit blood. Images are representative of ≥3 replicate experiments.

Stimulation of SaeRS by HNP-1 overcomes the necessity for VfrB.

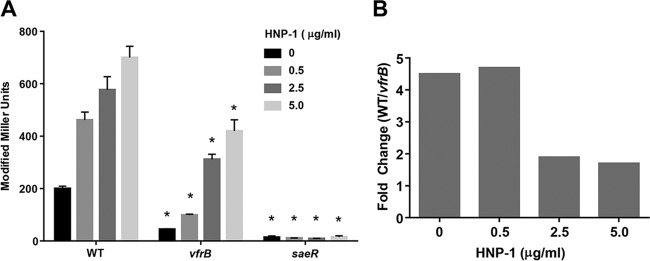

SaeRS has been shown to be activated by several antibiotics and α-defensins (17, 21), including human neutrophil peptide 1 (HNP-1), resulting in increased transcription of class I target genes such as coa (15–17). This occurs when extracellular HNP-1 interacts with an extracellular loop of SaeS (13). As an additional approach to the constitutive SaeS used above, we hypothesized that HNP-1 could be used to stimulate SaeS to levels that would bypass the need for VfrB in coa promoter expression. This hypothesis was tested by measuring expression from the Pcoa-lacZ fusion in response to several concentrations of HNP-1. Similar to the findings presented in Fig. 2, the coa promoter activity in the vfrB mutant was 4.5-fold lower than wild-type levels in the absence of HNP-1 under these growth conditions (Fig. 5). As expected based on previous studies (12, 15–17, 25), we observed a dose-dependent transcriptional response in the wild-type strain in the presence of 0, 0.5, 2.5, or 5.0 μg ml−1 HNP-1. The coa promoter activity in the vfrB mutant in the presence of low HNP-1 concentrations (0.5 μg ml−1) had a similar reduction (4.7-fold) as when no HNP-1 was added. At increased doses, however, HNP-1 was able to induce Pcoa in the absence of vfrB. Specifically, the coa promoter activity in response to 2.5 or 5.0 μg ml−1 HNP-1 was only 1.9-fold or 1.7-fold, respectively, lower in the vfrB mutant strain than in the wild-type strain. The coa expression in the saeR mutant strain remained at basal levels with all concentrations tested. Together, these data indicate that VfrB is an important activator of SaeRS under normal conditions but becomes dispensable under strong SaeS activation, using either a constitutive SaeS variant or sufficient levels of SaeS-stimulating compounds.

FIG 5.

Low-dosage HNP-1-mediated activation of SaeRS is dependent on VfrB. The β-galactosidase activity from the Pcoa-lacZ transcriptional fusion was measured at 5 h in TSB containing HNP-1 for wild-type (WT), vfrB mutant, and saeR mutant strains. Data in panel B are represented as fold changes in expression between the wild-type strain and the vfrB mutant. Error bars, SEMs (n = 3). *, P < 0.05, relative to wild-type strains under the same conditions, using Student's t test. Data are representative of ≥3 individual experiments.

Class I and class II promoter activity in response to exogenous fatty acids.

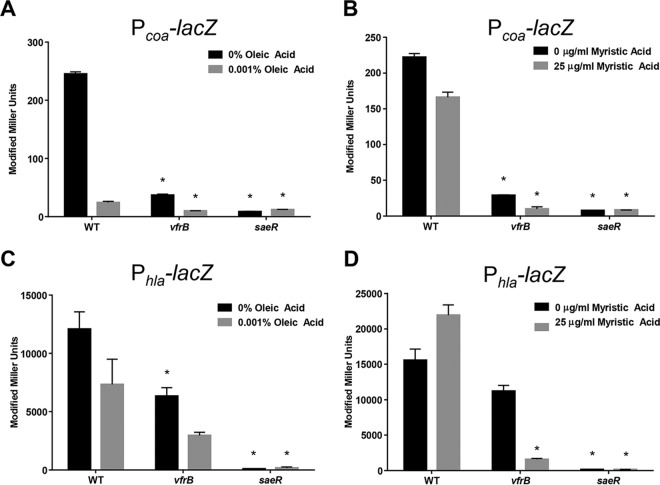

Previous studies demonstrated that VfrB is a fatty acid kinase involved in the incorporation of free unsaturated (oleic) or saturated (myristic) fatty acids into the cell membrane (27). Thus, we hypothesized that fatty acids may serve as activation stimuli for the SaeRS system through VfrB. If either oleic acid or myristic acid acts as a stimulatory signal, producing SaeR activation, then we would expect to observe increased expression of SaeRS target promoters in the wild-type strain and decreased expression in the vfrB mutant. To test this, we examined the expression of the lacZ reporter constructs in wild-type cells grown in the presence of increasing sublethal concentrations of oleic acid (0.000125% to 0.001%) or myristic acid (6.25 μg ml−1 to 50 μg ml−1). We found that both fatty acids, at all concentrations tested, decreased coa promoter activity, compared to a tryptic soy broth (TSB) control (data not shown). When the same experiment was performed using the hla reporter fusion strains, no difference was observed at most concentrations of oleic acid or myristic acid examined; however, there was an increase in hla promoter activity when 25 μg ml−1 myristic acid was added (data not shown).

From these initial analyses, 0.001% oleic acid and 25 μg ml−1 myristic acid in TSB were chosen as concentrations of fatty acids for analysis of class I and class II promoter expression in a vfrB mutant strain, compared to the wild-type strain. Transcriptional activity from the coa promoter in response to the addition of either oleic acid or myristic acid was decreased in both the wild-type and vfrB mutant strains, indicating that decreased expression resulting from exogenous fatty acid exposure is largely VfrB independent (Fig. 6A and B). When transcription from the hla promoter in response to oleic acid was examined, there was decreased expression in both the wild-type and vfrB mutant strains, compared to expression in TSB alone (Fig. 6C). In contrast, transcriptional activity levels in the wild-type strain carrying the hla reporter were similar whether myristic acid was present or absent in the medium (Fig. 6D). Interestingly, hla promoter activity was decreased 13.9-fold in the vfrB mutant strain, compared to the wild-type strain, in the presence of myristic acid. This demonstrates that VfrB is required for hla transcription at wild-type levels when exogenous myristic acid is present. Collectively, these results demonstrate that the downregulation of class I and class II promoter activity in response to oleic acid and class I promoter activity in response to myristic acid is VfrB independent. However, hla transcription in vfrB mutants in response to myristic acid is significantly hindered.

FIG 6.

Responses of Phla and Pcoa to exogenous fatty acids. The β-galactosidase activity from a Pcoa-lacZ (A and B) or Phla-lacZ (C and D) transcriptional fusion reporter was measured for wild-type (WT), vfrB mutant, and saeR mutant strains grown in TSB containing 0.001% oleic acid (A and C) or 25 μg/ml myristic acid (B and D) until the late exponential growth phase. Error bars, SEMs (n = 3). *, P < 0.05, relative to wild-type strains under the same conditions, using Student's t test. Data are representative of ≥3 individual experiments.

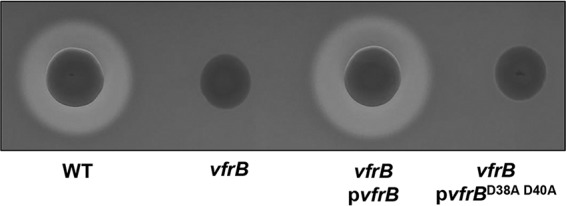

Conserved aspartic acid residues are required for VfrB function.

Although our data suggest that VfrB modulates SaeRS activity, the mechanism for this activation has yet to be determined. Previous bioinformatic analyses of VfrB (using the Pfam database at http://pfam.xfam.org/) revealed that this protein contains a DAK2 domain from amino acid 35 to amino acid 199 and a dihydroxyacetone kinase family domain from amino acid 237 to amino acid 548 (26). Furthermore, VfrB contains a conserved aspartic acid-glycine-aspartic acid (DGD) motif that has been demonstrated to be necessary for Mg2+ binding and ATP coordination in the dihydroxyacetone kinase (DhaK) of Citrobacter freundii (36). Based on these findings, we would expect that these aspartic acid residues would be essential for VfrB fatty acid kinase activity and thus its effects on SaeRS. Therefore, the vfrB-encoded aspartic acid residues D38 and D40 were mutated to alanine residues A38 and A40, respectively (vfrBD38A D40A). Following this, vfrBD38A D40A was expressed from a plasmid in the vfrB mutant strain, and hemolytic activity was assessed as a measure of (i) VfrB activity and (ii) expression of an Sae-dependent promoter. The vfrBD38A D40A complement strain was unable to rescue the hemolysis-deficient phenotype of the vfrB mutant (Fig. 7). In order to ensure that loss of hemolysis in the vfrBD38A D40A complement strain was not due to altered protein stability or solubility, we constructed C-terminal hexahistidine-tagged versions of VfrB and VfrBD38A D40A for analysis, since antibodies are not available for VfrB. As with the nontagged versions, the strain expressing His-tagged VfrBD38A D40A did not show Hla-dependent hemolysis (Fig. S3). In addition, we performed immunoblots with broth-grown cell extracts and were able to detect the protein at comparable steady-state levels. These results demonstrate the necessity of the D38 and D40 residues for the activity of VfrB, and they suggest that VfrB must be functionally active as a kinase in order to modulate the activity of the Sae system.

FIG 7.

D38 and D40 residues are required for VfrB activity. The hemolytic activity of the wild-type (WT) strain, a vfrB mutant strain, a vfrB mutant strain expressing vfrB (pvfrB), and a vfrB mutant strain expressing vfrB encoding alanine substitutions for D38 and D40 (pvfrBD38A D40A) was measured on TSA containing 5% rabbit blood. Images are representative of ≥3 replicate experiments.

DISCUSSION

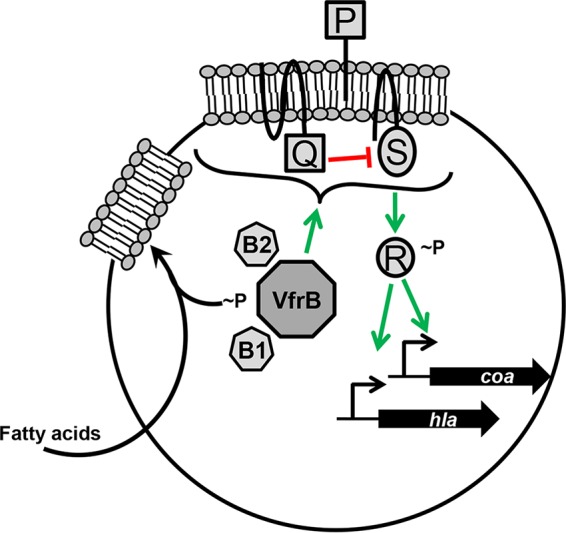

Herein, we present evidence supporting a model for VfrB involvement in modulating the SaeRS two-component system in S. aureus (Fig. 8). This study presents a new layer of regulatory control of this two-component system, which is still fairly elusive in terms of its precise activation stimuli and/or molecules. We propose that, in contrast to the already characterized accessory proteins SaeP and SaeQ, VfrB may act as a positive activation protein in this system. We have demonstrated that VfrB functions in the same pathway as SaeRS to positively regulate the production of α-hemolysin. This regulation by VfrB is required for activation of SaeRS-mediated transcription of both class I (coa) and class II (hla) target genes. Moreover, VfrB-mediated activation is growth phase and activation state dependent for both class I and class II target promoters.

FIG 8.

Model for the role of VfrB in the regulation of SaeRS in S. aureus. VfrB is a fatty acid kinase that interacts with the fatty acid-binding proteins FakB1 (B1) and FakB2 (B2) to utilize exogenous fatty acids. In addition to its function as a fatty acid kinase, VfrB positively regulates the SaeRS two-component system (depicted as P, Q, R, and S). Specifically, VfrB is required for the transcription of class I (coa) and class II (hla) target genes.

As the understanding of two-component systems continues to expand, more research is being done to understand how accessory or auxiliary proteins are involved in signal transduction in bacteria. These accessory proteins are commonly membrane associated, which allows for ideal spatial locations to signal a two-component system. Classic examples of these membrane-associated proteins are ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters that facilitate the extrusion of antibiotics and the activation of adjacent two-component systems in S. aureus (GraRS), Streptococcus mutans (BceRS), and Bacillus subtilis (BceRS) (37–39). One of the most well characterized of these systems is BceRS in B. subtilis, in which the BceAB ABC transporter is essential for detection of bacitracin and the resulting activation of the cognate BceRS, which underscores the importance of these accessory proteins in two-component system regulation (40). In addition to membrane-bound enzymes, there are examples of less well-characterized cytoplasmic auxiliary proteins. These proteins have been demonstrated to interact directly with two-component system proteins to regulate them positively when required. This has been well studied in Escherichia coli, in which the accessory protein PII of the NtrBC system, at high nitrogen levels, blocks autophosphorylation activities of the NtrB sensor kinase, in order to repress the transcription of genes required for nitrogen metabolism (reviewed in reference 41). This repression by PII is alleviated in the presence of low levels of nitrogen, when there is a requirement for the transcription of nitrogen metabolism genes. These different classes of auxiliary proteins in a wide range of bacteria demonstrate the variability that exists in two-component system regulation. Our study has demonstrated that VfrB functions as a cytoplasmic accessory protein involved in the positive regulation of SaeRS.

As is the case with other accessory proteins involved in the modulation of cognate transcriptional regulators, we found that VfrB functions in the same pathway as SaeRS to regulate virulence determinant production. This was first discovered with the observation that VfrB is necessary but not sufficient to control α-hemolysin production. This was evident when complementation of saeR or saeS mutations with vfrB on a multicopy plasmid did not rescue the nonhemolytic phenotype. It is noteworthy that the vfrB saeS double mutant strain was less hemolytic than the saeS single mutant strain. Moreover, when the vfrB saeS double mutant strain was complemented with vfrB, hemolysis was partially restored. This phenotype is distinct from that of the vfrB saeR double mutant strain complemented with vfrB, in which complementation did not restore hemolysis. We suggest that the partial restoration of hemolysis in the vfrB saeS double mutant strain upon complementation with vfrB is possible due to the presence of saeR, since this gene is located upstream of saeS. In other words, the saeS mutation does not inhibit the production of SaeR, which could be sufficient for transcription of the system at levels allowing some hla transcription and subsequent toxin production. This is perhaps not unexpected, because it has been documented for other two-component systems that deletion of a sensor histidine kinase does not result in the inability to mediate the transcription of target genes, due to cross regulation from other two-component systems (42–48). In conjunction with this, the absence of phosphatase activity provided by the sensor histidine kinase cannot prevent cross talk with other networks or small-molecule phospho-donors. Together, these results demonstrate that VfrB is involved in SaeRS modulation. Considering the necessity of both SaeR and SaeS, we postulate that the Sae-activating ability is achieved through the sensor kinase SaeS and not direct interaction with or phosphorylation of SaeR.

In addition to our observation that VfrB is required for the production of Hla, our transcriptional analyses revealed that VfrB is required for the transcription of both class I and class II promoter genes. Deletion of VfrB leads to greater reduction of the transcription of coa (class I promoter gene) than that of hla (class II promoter gene). This is not unexpected, because SaeRS-mediated transcription of class I target genes requires activation of the system; therefore, transcription of hla occurs even in the absence of elevated levels of phosphorylated SaeRS. The dependence on VfrB for transcription is less significant for class II promoter genes, leading to less pronounced differences in the expression of these genes, compared to the wild-type strain. An additional explanation for this discrepancy in the necessity of VfrB for class I and class II promoters is that class I promoters have two SaeR-binding sites, whereas class II promoters have a single SaeR-binding site (14); therefore, higher levels of phosphorylated SaeR are required to activate class I promoters. Finally, in addition to the regulation of hla by SaeRS, several other master regulatory factors (e.g., Agr, RNAIII, Rot, SarA, and SarT) influence transcription of the hemolysin (29–34), adding additional levels of regulation that affect expression. Thus, it is plausible that the complex regulatory mechanisms that control hla expression also contribute to VfrB having less effect on this class II gene than on coa. Moreover (and in agreement with coa transcriptional data), VfrB is also necessary in order to induce transcription from the Sae P1 promoter (also a class I promoter). Our finding that vfrB transcript levels were not altered in an saeR mutant are perhaps not unexpected, since the vfrB promoter region does not contain the GTTAAN6GTTAA repeat motif found in SaeRS target genes (14). Our findings indicate that, while VfrB modulates the activity of SaeRS, it is not itself regulated by the two-component system.

We determined that VfrB is required to positively modulate the SaeRS system under noninducing conditions; however, regulation of the system is different in activated states. This differential regulation was first observed when hla expression during the stationary growth phase was demonstrated to be VfrB independent. During this phase of growth, the expression of SaeRS is at maximal levels under standard growth conditions. Therefore, it seems that, when SaeRS is already expressed at high levels, there is enough phosphorylated SaeR to bind to the single SaeR-binding site of class II promoters, and VfrB is not required to further activate expression of the system. This hypothesis was strengthened by two additional analyses in which SaeRS was constitutively active (i.e., in the Newman background) and the system was activated upon the addition of HNP-1. In the Newman strain, the constitutive activation of SaeRS led to hemolysis even in the absence of VfrB, revealing that the highly active state bypasses the need for VfrB modulation. Similarly, when HNP-1 was used to activate SaeRS, VfrB was again dispensable for high-level activity of the two-component system. An additional explanation for why VfrB is required to mediate transcription of coa in response to low levels but not high levels of HNP-1 is that levels of saePQRS transcription in vfrB mutant strains is lower than that in wild-type strains. Thus, lower levels of SaeRS in the vfrB mutant would result in reduced transcription of coa in response to HNP-1. Moreover, the high-level phosphorylation state and long half-life of SaeR that were documented previously could contribute to the dispensability of VfrB when the system is overstimulated (14). Taken together, these results demonstrate that VfrB is an accessory protein required for the activation from basal activity to the full potential of the system. Once SaeRS is activated at a threshold level, it can circumvent the need for VfrB stimulation.

Since VfrB is a fatty acid kinase that is required for the incorporation of exogenous fatty acids into cells, we hypothesized that the presence of fatty acids is a stimulus for VfrB-mediated activation of SaeRS. However, the presence of an unsaturated fatty acid (oleic acid) did not upregulate the transcription of class I or class II target genes. Instead, the presence of oleic acid led to the downregulation of SaeRS-mediated genes in both wild-type and vfrB mutant strains. This finding is not unlike a previous observation that the major human skin fatty acid, cis-6-hexadecenoic acid, downregulated genes of the SaeRS regulon in S. aureus SH1000, through an undefined mechanism (49). Furthermore, we found that the addition of a saturated fatty acid (myristic acid) did not induce the transcription of coa in wild-type or vfrB mutant strains. However, VfrB is required for the transcription of hla when cells are exposed to exogenous myristic acid. Together, these results suggest that fatty acids are not direct signaling substrates necessary for VfrB-mediated activation of SaeRS.

Collectively, the data from this study indicate that VfrB modulates the activity of the SaeRS system, likely through VfrB serving as a positive activator of SaeR and SaeS activity. Alternatively, VfrB could act to repress the activity of SaeP and/or SaeQ, which act to dampen the SaeRS system to the preactivation state. In this scenario, the loss of VfrB would lead to increased activity of SaeP and SaeQ and thus decreased SaeRS-mediated transcription. The latter scenario is the least probable, as the positive effect of VfrB on SaeRS is observed even when the activities of SaeP and SaeQ are at low levels. As for the enzymatic activity of VfrB, we have demonstrated that the catalytic residues D38 and D40 are required for the production of α-hemolysin and a possible enzymatic mechanism for regulation. The requirement for a fatty acid kinase as a positive activator of a two-component system is novel with respect to the current understanding of bacterial transcriptional regulation. There are several other mechanisms through which VfrB could alter SaeRS activity. First, VfrB is a fatty acid kinase needed for exogenous fatty acid utilization, and it is plausible that vfrB mutants have altered membrane compositions that lead to altered SaeRS activation. Interestingly, SaeP is a lipoprotein that could be affected by such membrane alterations. Second, since VfrB phosphorylates fatty acids, it is possible that these products serve as signals or phospho-donors for the two-component system. Finally, VfrB or one of the FakB fatty acid carrier proteins could interact directly with SaeRS to alter activation. Current studies in our laboratory are aimed at elucidating the direct mechanism through which VfrB controls SaeRS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, media, and growth conditions.

Escherichia coli strains were grown in lysogeny broth (LB), with ampicillin (100 μg ml−1) or kanamycin (50 μg ml−1) for antibiotic selection when necessary. S. aureus strains were grown in TSB, with chloramphenicol (10 μg ml−1) or erythromycin (5 μg ml−1) for antibiotic selection when required. All strains were grown at a medium/flask ratio of 1:10, with shaking, at 250 rpm at 37°C unless otherwise stated. The strains used in this study are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Select strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| AH1263 | USA300 CA-MRSA strain LAC lacking LAC-p03 | 54 |

| CYL11481 | Newman SaeSP18L | 9 |

| JLB13 | Newman vfrB::ϕΝΣ | This study |

| JLB14 | Newman vfrB::ϕΝΣ SaeSP18L | This study |

| JLB15 | AH1263 saeR::ϕΝΣ | This study |

| JLB16 | AH1263 ΔvfrB saeR::ϕΝΣ | This study |

| JLB17 | AH1263 saeS::ϕΝΣ | This study |

| JLB18 | AH1263 ΔvfrB saeS::ϕΝΣ | This study |

| JLB2 | AH1263 ΔvfrB | 26 |

| JLB26 | AH1263 ΔvfrB SaeSL18P | This study |

| JLB29 | AH1263 SaeSL18P | This study |

| NE1296 | Strain containing saeS::ϕΝΣ | 55 |

| NE1622 | Strain containing saeR::ϕΝΣ | 55 |

| NE229 | Strain containing vfrB::ϕΝΣ | 55 |

| Newman | HA-MSSA strain | 56 |

| RN4220 | Highly transformable S. aureus | 57 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCK1 | pCR-Blunt II-TOPO containing vfrBD38A D40A | This study |

| pCK2 | vfrBD38A D40A complementation plasmid | This study |

| pCK9 | PsaeP3-lacZ reporter | This study |

| pCK13 | vfrB-His6 complementation plasmid | This study |

| pCK14 | vfrBD38A D40A-His6 complementation plasmid | This study |

| pCM28 | E. coli-S. aureus shuttle vector | 58 |

| pCR-Blunt II-TOPO | Cloning plasmid | Invitrogen |

| pJB1017 | Phla-lacZ reporter | This study |

| pJB1018 | Pcoa-lacZ reporter | This study |

| pJB165 | vfrB complementation plasmid | 26 |

| pJB185 | Promoterless codon-optimized lacZ; Ampr Cmr | This study |

| pJB38 | Temperature-sensitive allelic exchange plasmid | 59 |

| pJLB13 | saeSL18P allelic exchange plasmid | This study |

| pJLB4 | vfrB in pCR-Blunt II-TOPO | 26 |

ϕΝΣ indicates insertion of the bursa aurealis transposon encoding erythromycin resistance. Ampr (bla), resistance to ampicillin in E. coli; Cmr (cat), resistance to chloramphenicol in S. aureus; CA-MRSA, community-acquired methicillin-resistant S. aureus; HA-MSSA, hospital-acquired methicillin-sensitive S. aureus.

Construction of SaeRS-dependent reporter fusions.

In order to generate reporter plasmids, the E. coli lacZ gene was codon optimized for S. aureus and synthesized using GeneArt (ThermoFisher Scientific). This construct contains a custom-designed multiple cloning site (MCS) and removable translational initiation region (TIR) ribosome-binding site that we previously showed to enhance expression (50). The MCS-TIR-lacZ fragment was liberated from the plasmid provided by GeneArt using EcoRI and PstI and was ligated into the same sites of pCM28 to create pJB185. To create an hla promoter reporter, PCR was used to amplify the hla promoter from the AH1263 chromosome using primers JB21 and JB22 (all oligonucleotides are listed in Table 2). The resulting product was digested with EcoRI and NheI and ligated into EcoRI/XbaI-digested pJB185. The resulting plasmid, pJB1017, has Phla driving lacZ expression. The Pcoa-lacZ reporter plasmid pJB1018 was constructed in a similar manner. Pcoa was amplified from the AH1263 chromosome by PCR using primers JBKU25 and JBKU26. The PCR product was digested with EcoRI and XbaI and ligated into the same sites of pJB185. Lastly, the PsaeP3-lacZ reporter fusion plasmid pCK9 was generated in a similar manner. The P3 promoter of sae (16) was amplified from the AH1263 chromosome by PCR using primers CNK22 and CNK23. The resulting product was digested with EcoRI and BamHI and ligated into the same sites of pJB185. Reporter fusion plasmids were then introduced into AH1263 wild-type, vfrB, and saeR mutant stains, Newman wild-type and vfrB mutant strains, or Newman SaeSP18L and vfrB mutant strains via ϕ11-mediated transduction, as described previously (51).

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Name | Sequencea | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| CNK1 | P-CCAGcaGGTGcaACAGGAAC | This study |

| CNK2 | P-CACTGGATACACATTCAAAGAATCTACCAAATCTG | This study |

| CNK22 | ccggaattcCAGAGTGGTATAAGTGG | This study |

| CNK23 | cgggatccTTCACCTCTGTTCTTACG | This study |

| CNK26 | ggctgcagTTAatgatgatgatgatgatgTTCTACTGAAAAGAAATATTG | This study |

| JB5 | ccgctagcAATACAGGCAAGAAAGCTTAGGAGGAC | 26 |

| JB6 | ccgtcgaCTTTACCTGGGTATTCGGTATGCACGTGAAC | 26 |

| JB21 | ccgaattCTTGTACTGTTTGATATGGAACTCCTG | This study |

| JB22 | ccgctagCCATTTTCATCATCCTTCTATTTTTTAAAACG | This study |

| JB37 | CTTTAGAGGTCGTAAGAACAGAGGTGAAAAAATAGATG | This study |

| JB38 | GGTTAAACAGCTTGTAATTATTGTCGTTAAGGTC | This study |

| JB46 | ggcaattcGGATGATGAACAAGACATTGTAGACATTTGTC | This study |

| JB47 | P-TATACTCGATACGACGCCAATAATGATTTGAC | This study |

| JB48 | P-CCATTAACTTCAACTATTTTAGCAATTGCATATATT | This study |

| JB49 | ccgtcgacTGTCGATAGTATCTTGATCTTCGTTTTCAC | This study |

| JBHEM1 | ccggatccATGAGTACCTCCTTTAATAAATATAAATACAC | 26 |

| JBHEM2 | ggctgcagATACTTTTAACCCGCAATATCACTAAAATAGC | 26 |

| JBKU25 | ccgaattcGAATTGTAAATACTTTCTAATCTTTGTTTCGC | This study |

| JBKU26 | ggtctagaTGCGCCTAGCGAAATTATTTGC | This study |

| JBRT3 | ATCGCAATGGTTGACTACGA | This study |

| JBRT4 | CGAAGATGACGTGAGCTTTTT | This study |

| RT-sigA-F | AACTGAATCCAAGTGATCTTAGTG | 53 |

| RT-sigA-R | TCATCACCTTGTTCAATACGTTTG | 53 |

Primer sequences are presented 5′ to 3′, and lowercase italic letters indicate nonhomologous bases added for cloning purposes. P indicates the addition of a 5′ phosphate to allow ligation of PCR products.

Transfer of saeR::ϕΝΣ, saeS::ϕΝΣ, and vfrB::ϕΝΣ.

A Newman vfrB mutant was constructed by moving the Nebraska Transposon Mutant Library bursa aurealis insertion from NE229 into the Newman strain via ϕ11-mediated transduction. Disruption of vfrB was verified using primers JB5 and JB6. Similarly, to construct saeR and saeS mutants, the transposon insertion was transferred from NE1622 (transposon insertion at nucleotide 280 of 687 nucleotides) and NE1296 (transposon insertion at nucleotide 83 of 1,056 nucleotides), respectively, into AH1263 or the ΔvfrB mutant. The insertions into saeR and saeS were confirmed using primers JB37 and JB38, while ΔvfrB was confirmed using primers JBHEM1 and JBHEM2.

Construction of SaeSL18P constitutively active strains.

In order to generate constitutively active SaeS strains, an allelic exchange plasmid was constructed to replace native saeS with a mutated gene encoding SaeSL18P. Primers were designed to amplify ∼750 bp flanking the bases to be mutated. The sequence upstream was amplified from the AH1263 chromosome by PCR using primers JB46 and JB47. The altered base pairs were incorporated into primer JB48; the primer was paired with JB49 to amplify the mutagenesis target site and downstream sequence. Primers JB47 and JB48 were 5′ phosphorylated so that the resulting PCR products could be ligated together. The upstream product was digested with EcoRI, while the downstream product was cleaved with SalI. The digested products were ligated into EcoRI/SalI-digested pJB38 in a single step. The resulting plasmid, pJLB13, was transferred into S. aureus RN4220 by electroporation. To construct mutants, pJLB13 was transferred into AH1263 and the vfrB mutant via transduction using ϕ11, as described previously (51), followed by allelic exchange performed as described previously (26, 52). The resulting colonies were screened for the saeSL18P mutation by sequencing of a PCR product including the mutated site.

Construction of vfrB and vfrBD38A D40A mutant complementation plasmids.

In order to generate a vfrB allele encoding D38A and D40A mutations (vfrBD38A D40A), the 5′-phosphorylated primers CNK1 and CNK2, containing the mutations, were used to amplify pJLB4. The resulting product was ligated and treated with DpnI to remove template DNA, creating pCK1. The desired mutations were confirmed by sequencing of vfrB in pCK1, and this plasmid was used as a template to amplify vfrBD38A D40A using primers JBHEM1 and JBHEM2. The resulting PCR product was digested with BamHI and PstI and ligated into BamHI/PstI-digested pCM28, creating pCK2. In order to construct a hexahistidine-tagged vfrB complementation plasmid, vfrB was amplified using primers JBHEM1 and CK26, with pJB165 as the template DNA. The PCR product was then digested with BamHI and PstI and ligated into BamHI/PstI-digested pCM28, creating pCK13. The hexahistidine-tagged vfrBD38A D40A complementation plasmid (pCK14) was created like pCK13, using pCK2 as the template DNA for amplification. The resulting plasmids were electroporated into RN4220 and transferred to the AH1263 wild-type or vfrB mutant strains via ϕ11-mediated transduction, as described previously (51).

Hemolytic activity.

Hemolytic activity on tryptic soy agar (TSA) containing 0.5% rabbit blood was determined as described previously (26). Quantitative hemolysis assays were performed with cells grown to the late exponential growth phase as described previously, with the modification of analyzing cell lysis at an optical density at 650 nm (OD650) (26).

Analysis of β-galactosidase activity.

β-Galactosidase activity was determined as described previously, with minor modifications (53). Briefly, 1-ml samples were harvested from 12.5-ml late-exponential-growth-phase (5 h) or stationary-growth-phase (8 h) cultures, pelleted, and resuspended in 1.2 ml Z-buffer. For HNP-1 experiments, cultures were grown in 1-ml volumes in 1.7-ml tubes in the presence of 0, 0.5, 2.5, or 5.0 μg ml−1 HNP-1. The cells were then lysed using a FastPrep-24 5G homogenizer (MP Biomedicals), according to the manufacturer's recommended settings for S. aureus cells. Subsequently, β-galactosidase activity was detected by adding 140 μl of ortho-nitrophenyl-β-galactoside (ONPG) (4 mg ml−1 [wt/vol]) to 700 μl of cell lysates and allowing the reaction to turn slightly yellow (OD420 of less than 1.0), at 37°C. Once the samples appeared yellow, the reaction was stopped with 200 μl of 1 M sodium bicarbonate, to allow the measurement of OD420 values. The β-galactosidase activity, in modified Miller units, was calculated based on protein concentrations determined using the Bradford assay with the Bio-Rad protein concentration reagent.

Reverse transcription-quantitative real-time PCR.

RNA was extracted, using an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen), from strains grown to the late exponential growth phase. DNA contaminants were then removed from the RNA samples using a DNA-free kit (Ambion). RNA samples were standardized to the same concentration of total RNA (500 ng) and used as the templates for cDNA synthesis using a QuantiTect reverse transcription kit (Qiagen). The resulting cDNA was diluted 1:50 and used as the template DNA in quantitative PCRs using FastStart Essential DNA Green Master Mix, in a LightCycler 96 system (Roche). Primers JBRT3 and JBRT4 were used to amplify saeP. As an internal control, primers RT-sigA-F and RT-sigA-R were used to amplify sigA (rpoD).

Immunoblot analysis.

AH1263 wild-type and vfrB mutant strains harboring pCK13, pCK14, or pCM28 (empty vector control) were grown to the late exponential growth phase and pelleted by centrifugation at 4°C. Cell pellets were resuspended in 500 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed using a FastPrep-24 5G homogenizer (MP Biomedicals), according to the manufacturer's recommended settings for S. aureus cells. Cellular debris was pelleted by centrifugation, and the supernatant, containing soluble cellular proteins, was standardized to the same protein concentration (60 μg) for each sample. Protein samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes using a Trans-Blot Turbo blotting system (Bio-Rad), according to the manufacturer's recommended protocol. Detection of the 6-histidine tag was performed using a 6×His tag antibody (Invitrogen) with the Li-Cor Quick Western kit and an Odyssey imager, according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Chia Lee (University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences) for providing the Newman and CYL11481 strains and Pamela Hall (University of New Mexico) for her technical assistance.

Research reported in this publication was supported, in part, by National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant P30-GM103326 (pilot project, to J.L.B.), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases under award R01AI121073 (J.L.B.), and NIH grant P01AI83211. C.N.K. was supported, in part, by a University of Kansas Medical Center Biomedical Research Training Program fellowship.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00828-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Becker RE, Bubeck Wardenburg J. 2015. Staphylococcus aureus and the skin: a longstanding and complex interaction. Skinmed 13:111–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duerden B, Fry C, Johnson AP, Wilcox MH. 2015. The control of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus blood stream infections in England. Open Forum Infect Dis 2:ofv035. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofv035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray RJ. 2005. Staphylococcus aureus infective endocarditis: diagnosis and management guidelines. Intern Med J 35(Suppl 2):S25–S44. doi: 10.1111/j.1444-0903.2005.00978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pendleton A, Kocher MS. 2015. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bone and joint infections in children. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 23:29–37. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-23-01-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanders JE, Garcia SE. 2015. Evidence-based management of skin and soft-tissue infections in pediatric patients in the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Med Pract 12:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung AL, Bayer AS, Zhang G, Gresham H, Xiong YQ. 2004. Regulation of virulence determinants in vitro and in vivo in Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 40:1–9. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00309-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cue D, Junecko JM, Lei MG, Blevins JS, Smeltzer MS, Lee CY. 2015. SaeRS-dependent inhibition of biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus Newman. PLoS One 10:e0123027. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giraudo AT, Cheung AL, Nagel R. 1997. The sae locus of Staphylococcus aureus controls exoprotein synthesis at the transcriptional level. Arch Microbiol 168:53–58. doi: 10.1007/s002030050469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luong TT, Sau K, Roux C, Sau S, Dunman PM, Lee CY. 2011. Staphylococcus aureus ClpC divergently regulates capsule via sae and codY in strain Newman but activates capsule via codY in strain UAMS-1 and in strain Newman with repaired saeS. J Bacteriol 193:686–694. doi: 10.1128/JB.00987-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mrak LN, Zielinska AK, Beenken KE, Mrak IN, Atwood DN, Griffin LM, Lee CY, Smeltzer MS. 2012. saeRS and sarA act synergistically to repress protease production and promote biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS One 7:e38453. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Voyich JM, Vuong C, DeWald M, Nygaard TK, Kocianova S, Griffith S, Jones J, Iverson C, Sturdevant DE, Braughton KR, Whitney AR, Otto M, DeLeo FR. 2009. The SaeR/S gene regulatory system is essential for innate immune evasion by Staphylococcus aureus. J Infect Dis 199:1698–1706. doi: 10.1086/598967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flack CE, Zurek OW, Meishery DD, Pallister KB, Malone CL, Horswill AR, Voyich JM. 2014. Differential regulation of staphylococcal virulence by the sensor kinase SaeS in response to neutrophil-derived stimuli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:E2037–E2045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322125111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Q, Cho H, Yeo WS, Bae T. 2015. The extracytoplasmic linker peptide of the sensor protein SaeS tunes the kinase activity required for staphylococcal virulence in response to host signals. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004799. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun F, Li C, Jeong D, Sohn C, He C, Bae T. 2010. In the Staphylococcus aureus two-component system sae, the response regulator SaeR binds to a direct repeat sequence and DNA binding requires phosphorylation by the sensor kinase SaeS. J Bacteriol 192:2111–2127. doi: 10.1128/JB.01524-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeong DW, Cho H, Jones MB, Shatzkes K, Sun F, Ji Q, Liu Q, Peterson SN, He C, Bae T. 2012. The auxiliary protein complex SaePQ activates the phosphatase activity of sensor kinase SaeS in the SaeRS two-component system of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol 86:331–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08198.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeong DW, Cho H, Lee H, Li C, Garza J, Fried M, Bae T. 2011. Identification of the P3 promoter and distinct roles of the two promoters of the SaeRS two-component system in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 193:4672–4684. doi: 10.1128/JB.00353-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geiger T, Goerke C, Mainiero M, Kraus D, Wolz C. 2008. The virulence regulator Sae of Staphylococcus aureus: promoter activities and response to phagocytosis-related signals. J Bacteriol 190:3419–3428. doi: 10.1128/JB.01927-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinhuber A, Goerke C, Bayer MG, Doring G, Wolz C. 2003. Molecular architecture of the regulatory locus sae of Staphylococcus aureus and its impact on expression of virulence factors. J Bacteriol 185:6278–6286. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.21.6278-6286.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Novick RP, Jiang D. 2003. The staphylococcal saeRS system coordinates environmental signals with agr quorum sensing. Microbiology 149:2709–2717. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26575-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuroda H, Kuroda M, Cui L, Hiramatsu K. 2007. Subinhibitory concentrations of β-lactam induce haemolytic activity in Staphylococcus aureus through the SaeRS two-component system. FEMS Microbiol Lett 268:98–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuroda M, Kuroda H, Oshima T, Takeuchi F, Mori H, Hiramatsu K. 2003. Two-component system VraSR positively modulates the regulation of cell-wall biosynthesis pathway in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol 49:807–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho H, Jeong DW, Liu Q, Yeo WS, Vogl T, Skaar EP, Chazin WJ, Bae T. 2015. Calprotectin increases the activity of the SaeRS two component system and murine mortality during Staphylococcus aureus infections. PLoS Pathog 11:e1005026. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mainiero M, Goerke C, Geiger T, Gonser C, Herbert S, Wolz C. 2010. Differential target gene activation by the Staphylococcus aureus two-component system saeRS. J Bacteriol 192:613–623. doi: 10.1128/JB.01242-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogasch K, Ruhmling V, Pane-Farre J, Hoper D, Weinberg C, Fuchs S, Schmudde M, Broker BM, Wolz C, Hecker M, Engelmann S. 2006. Influence of the two-component system SaeRS on global gene expression in two different Staphylococcus aureus strains. J Bacteriol 188:7742–7758. doi: 10.1128/JB.00555-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cho H, Jeong DW, Li C, Bae T. 2012. Organizational requirements of the SaeR binding sites for a functional P1 promoter of the sae operon in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 194:2865–2876. doi: 10.1128/JB.06771-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bose JL, Daly SM, Hall PR, Bayles KW. 2014. Identification of the Staphylococcus aureus vfrAB operon, a novel virulence factor regulatory locus. Infect Immun 82:1813–1822. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01655-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parsons JB, Broussard TC, Bose JL, Rosch JW, Jackson P, Subramanian C, Rock CO. 2014. Identification of a two-component fatty acid kinase responsible for host fatty acid incorporation by Staphylococcus aureus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:10532–10537. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1408797111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giraudo AT, Raspanti CG, Calzolari A, Nagel R. 1994. Characterization of a Tn551-mutant of Staphylococcus aureus defective in the production of several exoproteins. Can J Microbiol 40:677–681. doi: 10.1139/m94-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vandenesch F, Kornblum J, Novick RP. 1991. A temporal signal, independent of agr, is required for hla but not spa transcription in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 173:6313–6320. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.20.6313-6320.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheung AL, Projan SJ. 1994. Cloning and sequencing of sarA of Staphylococcus aureus, a gene required for the expression of agr. J Bacteriol 176:4168–4172. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.13.4168-4172.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morfeldt E, Taylor D, von Gabain A, Arvidson S. 1995. Activation of alpha-toxin translation in Staphylococcus aureus by the trans-encoded antisense RNA, RNAIII. EMBO J 14:4569–4577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McNamara PJ, Milligan-Monroe KC, Khalili S, Proctor RA. 2000. Identification, cloning, and initial characterization of rot, a locus encoding a regulator of virulence factor expression in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 182:3197–3203. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.11.3197-3203.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidt KA, Manna AC, Gill S, Cheung AL. 2001. SarT, a repressor of α-hemolysin in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun 69:4749–4758. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.8.4749-4758.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blevins JS, Beenken KE, Elasri MO, Hurlburt BK, Smeltzer MS. 2002. Strain-dependent differences in the regulatory roles of sarA and agr in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun 70:470–480. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.2.470-480.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lebeau C, Vandenesch F, Greenland T, Novick RP, Etienne J. 1994. Coagulase expression in Staphylococcus aureus is positively and negatively modulated by an agr-dependent mechanism. J Bacteriol 176:5534–5536. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.17.5534-5536.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siebold C, Arnold I, Garcia-Alles LF, Baumann U, Erni B. 2003. Crystal structure of the Citrobacter freundii dihydroxyacetone kinase reveals an eight-stranded α-helical barrel ATP-binding domain. J Biol Chem 278:48236–48244. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305942200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dintner S, Staron A, Berchtold E, Petri T, Mascher T, Gebhard S. 2011. Coevolution of ABC transporters and two-component regulatory systems as resistance modules against antimicrobial peptides in Firmicutes bacteria. J Bacteriol 193:3851–3862. doi: 10.1128/JB.05175-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ouyang J, Tian XL, Versey J, Wishart A, Li YH. 2010. The BceABRS four-component system regulates the bacitracin-induced cell envelope stress response in Streptococcus mutans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:3895–3906. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01802-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rietkotter E, Hoyer D, Mascher T. 2008. Bacitracin sensing in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol 68:768–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bernard R, Guiseppi A, Chippaux M, Foglino M, Denizot F. 2007. Resistance to bacitracin in Bacillus subtilis: unexpected requirement of the BceAB ABC transporter in the control of expression of its own structural genes. J Bacteriol 189:8636–8642. doi: 10.1128/JB.01132-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ninfa AJ, Jiang P. 2005. PII signal transduction proteins: sensors of α-ketoglutarate that regulate nitrogen metabolism. Curr Opin Microbiol 8:168–173. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Henke JM, Bassler BL. 2004. Three parallel quorum-sensing systems regulate gene expression in Vibrio harveyi. J Bacteriol 186:6902–6914. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.20.6902-6914.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jiang M, Shao W, Perego M, Hoch JA. 2000. Multiple histidine kinases regulate entry into stationary phase and sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol 38:535–542. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laub MT, Goulian M. 2007. Specificity in two-component signal transduction pathways. Annu Rev Genet 41:121–145. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.042007.170548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mehta P, Goyal S, Long T, Bassler BL, Wingreen NS. 2009. Information processing and signal integration in bacterial quorum sensing. Mol Syst Biol 5:325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ninfa AJ. 1991. Protein phosphorylation and the regulation of cellular processes by the homologous two-component regulatory systems of bacteria. Genet Eng (N Y) 13:39–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wanner BL. 1992. Is cross regulation by phosphorylation of two-component response regulator proteins important in bacteria? J Bacteriol 174:2053–2058. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.7.2053-2058.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamamoto K, Hirao K, Oshima T, Aiba H, Utsumi R, Ishihama A. 2005. Functional characterization in vitro of all two-component signal transduction systems from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 280:1448–1456. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410104200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Neumann Y, Ohlsen K, Donat S, Engelmann S, Kusch H, Albrecht D, Cartron M, Hurd A, Foster SJ. 2015. The effect of skin fatty acids on Staphylococcus aureus. Arch Microbiol 197:245–267. doi: 10.1007/s00203-014-1048-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bose JL. 2014. Genetic manipulation of staphylococci. Methods Mol Biol 1106:101–111. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-736-5_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krausz KL, Bose JL. 2016. Bacteriophage transduction in Staphylococcus aureus: broth-based method. Methods Mol Biol 1373:63–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lehman MK, Bose JL, Bayles KW. 2016. Allelic exchange. Methods Mol Biol 1373:89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lehman MK, Bose JL, Sharma-Kuinkel BK, Moormeier DE, Endres JL, Sadykov MR, Biswas I, Bayles KW. 2015. Identification of the amino acids essential for LytSR-mediated signal transduction in Staphylococcus aureus and their roles in biofilm-specific gene expression. Mol Microbiol 95:723–737. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boles BR, Thoendel M, Roth AJ, Horswill AR. 2010. Identification of genes involved in polysaccharide-independent Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation. PLoS One 5:e10146. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fey PD, Endres JL, Yajjala VK, Widhelm TJ, Boissy RJ, Bose JL, Bayles KW. 2013. A genetic resource for rapid and comprehensive phenotype screening of nonessential Staphylococcus aureus genes. mBio 4:e00537-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Duthie ES, Lorenz LL. 1952. Staphylococcal coagulase: mode of action and antigenicity. J Gen Microbiol 6:95–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kreiswirth BN, Lofdahl S, Betley MJ, O'Reilly M, Schlievert PM, Bergdoll MS, Novick RP. 1983. The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature 305:709–712. doi: 10.1038/305709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pang YY, Schwartz J, Thoendel M, Ackermann LW, Horswill AR, Nauseef WM. 2010. agr-Dependent interactions of Staphylococcus aureus USA300 with human polymorphonuclear neutrophils. J Innate Immun 2:546–559. doi: 10.1159/000319855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bose JL, Fey PD, Bayles KW. 2013. Genetic tools to enhance the study of gene function and regulation in Staphylococcus aureus. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:2218–2224. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00136-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.