Abstract

Background

Point-of-care testing (POCT) of coagulation has been proven to be of great value in accelerating emergency treatment. Specific POCT for direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC) is not available, but the effects of DOAC on established POCT have been described. We aimed to determine the diagnostic accuracy of Hemochron® Signature coagulation POCT to qualitatively rule out relevant concentrations of apixaban, rivaroxaban, and dabigatran in real-life patients.

Methods

We enrolled 68 patients receiving apixaban, rivaroxaban, or dabigatran and obtained blood samples at six pre-specified time points. Coagulation testing was performed using prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (PT/INR), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), and activated clotting time (ACT+ and ACT-low range) POCT cards. For comparison, laboratory-based assays of diluted thrombin time (Hemoclot) and anti-Xa activity were conducted. DOAC concentrations were determined by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry.

Results

Four hundred and three samples were collected. POCT results of PT/INR and ACT+ correlated with both rivaroxaban and dabigatran concentrations. Insufficient correlation was found for apixaban. Rivaroxaban concentrations at <30 and <100 ng/mL were detected with >95% specificity at PT/INR POCT ≤1.0 and ≤1.1 and ACT+ POCT ≤120 and ≤130 s. Dabigatran concentrations at <30 and <50 ng/mL were detected with >95% specificity at PT/INR POCT ≤1.1 and ≤1.2 and ACT+ POCT ≤100 s.

Conclusions

Hemochron® Signature POCT can be a fast and reliable alternative for guiding emergency treatment during rivaroxaban and dabigatran therapy. It allows the rapid identification of a relevant fraction of patients that can be treated immediately without the need to await the results of much slower laboratory-based coagulation tests.

Trial registration

Unique identifier, NCT02371070. Retrospectively registered on 18 February 2015.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13054-017-1619-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Point-of-care testing, POCT, Direct oral anticoagulants, DOAC, Non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants, NOAC, Emergency surgery, Anticoagulation reversal, Thrombolysis, Stroke

Background

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC) are being increasingly prescribed. Consequentially, more DOAC-treated patients are admitted to emergency units across all clinical specialties. Importantly, emergency coagulation testing in DOAC-treated patients has not been solved, which complicates emergency treatment decisions such as emergency surgery, anticoagulation reversal, and thrombolysis in ischaemic stroke.

In patients receiving vitamin K antagonists (VKA), point-of-care testing (POCT) of coagulation has proven its great value in accelerating emergency treatment [1]. Although DOAC-specific POCT is not currently available, results obtained by our group suggest that relevant plasma concentrations of rivaroxaban can be qualitatively ruled out with CoaguChek® (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), a prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (PT/INR) POCT designed for VKA monitoring [2]. However, CoaguChek® lacked sensitivity to apixaban and dabigatran.

Hemochron® Signature (ITC, Edison, NJ, USA) is another coagulation POCT that uses a different PT/INR assay to CoaguChek® and has additional measuring capability for activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and activated clotting time (ACT). Previous reports indicate that Hemochron® Signature is responsive to rivaroxaban and dabigatran [3–7]. However, these reports aimed at quantitative measurements rather than qualitatively ruling out low but relevant DOAC concentrations, and used either artificially DOAC-spiked plasma samples [3, 4] or they only comprised a few samples with low DOAC concentrations [5–7]. Furthermore, the utility of Hemochron® Signature to measure the effects of apixaban on coagulation effects has never been reported. Thus, the diagnostic value of Hemochron® Signature in guiding emergency treatment decisions in DOAC-treated patients has not been clarified.

Methods

Study aim and design

We aimed to determine the diagnostic accuracy of Hemochron® Signature to qualitatively rule out relevant concentrations of apixaban, rivaroxaban, and dabigatran in real-life patients.

The study was a single-centre, prospective observational trial with blinded end-point assessment. The Clinical Trial Registration Information unique identifier is NCT02371070.

Setting and eligibility criteria

The study was conducted at the Department of Neurology & Stroke and the Department of Cardiology and Cardiovascular Medicine of Tübingen University Hospital, Tübingen, Germany, a tertiary care facility. Patients receiving first doses of apixaban, rivaroxaban, or dabigatran were enrolled. Exclusion criteria were known coagulopathy, abnormal coagulation at baseline (PT >13 s/Quick <70%/INR >1.2 or aPTT >37 s), intake of VKA or DOAC within 14 days, low-molecular-weight heparins within 24 h or unfractionated heparin within 12 h prior to DOAC intake. Use of antiplatelet agents was permitted.

Predominantly low dabigatran concentrations in these samples required inclusion of additional samples from patients on maintenance therapy with dabigatran. The same exclusion criteria as above applied, except that abnormal coagulation at baseline (due to dabigatran intake) was allowed.

Sample collection

Six blood samples were collected from each subject via an indwelling venous catheter or venipuncture: before DOAC intake, 30 min and 1, 2, and 8 h after intake, and at trough (12 h for apixaban and dabigatran, 24 h for rivaroxaban).

POCT and laboratory-based coagulation testing

Bedside POCT of PT/INR, aPTT and ACT was conducted from whole blood. ACT was measured using ACT plus (ACT+) and ACT-low range (ACT-LR) test cards that contain different reagents and cover different measurement ranges. Further samples were collected in 3.2% sodium-citrate tubes (Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany), and instantly centrifuged to acquire plasma. Laboratory-based anti-Xa activity was measured using Chromogenix COAMATIC Heparin Test on an ACL TOP 700 (Instrumentation Laboratory, Kirchheim, Germany). TECHNOVIEW calibrators (Technoclone, Vienna, Austria) were used to determine apixaban and rivaroxaban concentrations with limits of quantification of 10 and 18 ng/mL. Remaining plasma aliquots were stored at –80 °C until testing of diluted thrombin time (dTT; Hemoclot assay, Hyphen BioMed, Neuville-sur-Oise, France). As the gold standard, DOAC concentrations were determined by ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS) [8]. All coagulation testing was performed according to manufacturers’ instructions by thoroughly trained investigators and technicians.

Blinding

All laboratory-based tests, including UPLC-MS, were conducted and interpreted by technicians blinded to POCT results.

Definition of relevant DOAC concentrations

Our analyses were based on two likely emergency scenarios (Table 1). First, we investigated if POCT can be used to detect DOAC concentrations proposed as safe for surgical procedures [9–12]. As two of the proposed safe-for-treatment thresholds for dabigatran are practically identical (<48 ng/mL and <50 ng/mL), we chose to evaluate the <50 ng/mL threshold only. For apixaban a concentration threshold that permits surgery is currently unknown [13]. Second, we evaluated concentrations that may allow thrombolysis in ischaemic stroke according to an expert recommendation [14].

Table 1.

Investigated concentration thresholds

| Investigated concentrations | Rivaroxaban (ng/mL) | Apixaban (ng/mL) | Dabigatran (ng/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOAC concentrations proposed as safe for surgery [10–12] | 30 | NA | 30, 48, 50 |

| DOAC concentrations that may permit thrombolysis with rtPA [14] | 100 | 10 | 50 |

DOAC direct oral anticoagulants, NA not available, rtPA recombinant tissue plasminogen activator

Statistics

For test performance analyses, results of samples (all baseline samples, all samples per DOAC) were pooled in order to obtain a clinically relevant concentration spectrum. SPSS v23 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistics. Confidence intervals for proportions, i.e. diagnostic sensitivity and specificity, were calculated according to the efficient-score method using the free online VassarStats Clinical Calculator 1 [15]. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to estimate the strength of correlations between coagulation assays and DOAC concentrations. Correlation strength was graded as proposed by Evans: <0.20 very weak, 0.20–0.39 weak, 0.40–0.59 moderate, 0.60–0.79 strong, and >0.80 very strong [16]. Fisher’s exact test was calculated to determine differences in the proportions of baseline POCT results between the study groups and to examine the association between coagulation test results and DOAC concentrations dichotomized to concentrations below and above the chosen safe-for-treatment thresholds (Table 1). Diagnostic accuracy of coagulation tests at different cut-off points was expressed in terms of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and likelihood ratio. Sensitivity was defined as the percentage of samples with DOAC concentrations below the chosen safe-for-treatment threshold that were correctly identified as eligible for treatment. Correspondingly, specificity was defined as the percentage of samples with DOAC concentrations above the corresponding threshold that were correctly identified as not eligible. Specificity >95% was defined as sufficient for clinical application. PPV was defined as the percentage of samples with DOAC concentrations below the chosen safe-for-treatment threshold of all samples identified as eligible for treatment. NPV was defined as the percentage of samples with DOAC concentrations above the chosen safe-for-treatment threshold of all samples identified as not eligible for treatment. All DOAC concentrations are reported as median and interquartile range (IQR). Sensitivity and specificity are given with two-sided 95% confidence intervals.

Results

We enrolled 60 patients (n = 20 per DOAC) receiving first doses of DOAC and eight patients on dabigatran maintenance therapy between February 2014 and November 2015. Patient characteristics and baseline laboratory values are provided as part of Additional file 1: Tables S1 and S2).

Samples and DOAC concentrations

Of 408 planned samples, 403 were collected (apixaban n = 117, rivaroxaban n = 118, dabigatran n = 168). Five samples could not be analysed due to POCT malfunction.

DOAC were not detected by UPLC-MS in any baseline sample acquired before first DOAC intake (n = 60). Samples collected after DOAC intake contained a median concentration of 57.2 ng/mL apixaban (IQR 35.3–101.2, n = 97), 99.3 ng/mL rivaroxaban (IQR 25.7–184.3, n = 98), and 29.0 ng/mL dabigatran (IQR 10.7–72.3, n = 148). Median trough dabigatran concentrations were significantly lower after the first dose than during maintenance therapy (16.3 versus 81.8 ng/mL, p < 0.001).

Correlation between POCT results and DOAC concentrations

POCT of baseline samples before first DOAC intake showed no difference between DOAC groups. Correlations between POCT results and apixaban concentrations were weak for PT/INR (r = 0.37, p < 0.001) and moderate for ACT+ (r = 0.48, p < 0.001). No correlation was found for aPTT (p = 0.857) or ACT-LR (p = 0.174). For rivaroxaban, correlation was strong for PT/INR and ACT+ (r = 0.79 and 0.78, both p < 0.001) and weak for aPTT and ACT-LR (r = 0.399 and 0.383, both p <0.001). Dabigatran concentrations correlated strongly with all test cards (PT/INR, r = 0.75; aPTT, r = 0.75; ACT-LR, r = 0.69; ACT+, r = 0.67; all p < 0.001). Figure 1 shows the relations of the four POCT test cards to DOAC concentrations.

Fig. 1.

Hemochron® Signature POCT results (lines 1 to 4) plotted against concentrations of a apixaban, b rivaroxaban, and c dabigatran. Line 1: prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (PT/INR) POCT; line 2: activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) POCT; line 3: activated clotting time-low range (ACT-LR) POCT; line 4: ACT+ POCT. n = 118 samples for rivaroxaban, n = 117 samples for apixaban, and n = 168 samples for dabigatran

Due to insufficient correlation strength for apixaban, we limited all further analyses to rivaroxaban and dabigatran. To maximize clinical applicability, we focused on the two test cards that provided strong correlation to both rivaroxaban and dabigatran, i.e. PT/INR and ACT+.

Diagnostic accuracy of POCT

Rivaroxaban concentration was <30 ng/mL in 46/118 and <100 ng/mL in 79/118 samples. Dabigatran concentration was <30 ng/mL in 95/168 and <50 ng/mL in 117/168 samples. PT/INR and ACT+ POCT results for samples below and above each of the investigated safe-for-treatment thresholds differed significantly (all p < 0.001; Fig. 2). For reasons of clarity and comparison, test accuracy calculations are presented in Tables 2 and 3; additional calculations for aPTT and ACT-LR POCT cards are presented as part of Additional file 1: Table S3).

Fig. 2.

a Distribution of rivaroxaban concentrations found at different Hemochron® Signature POCT results of prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (PT/INR) and activated clotting time plus (ACT+) test cards and at different anti-Xa activities (n = 118 samples). b Distribution of dabigatran concentrations found at different Hemochron® Signature POCT results of PT/INR and ACT+ test cards, and at different Hemoclot assay results (n = 168 samples)

Table 2.

Diagnostic accuracy of Hemochron® Signature POCT for rivaroxaban

| Coagulation test result | Threshold (ng/mL) | Specificity (%) | Sensitivity (%) | LR | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POCT PT ≤1.0 | <30 | 97 (89–100) | 33 (20–48) | 11.6 | 88 | 69 |

| POCT PT ≤1.1 | <100 | 96 (85–99) | 38 (27–50) | 9.0 | 93 | 52 |

| POCT ACT+ ≤120 s | <30 | 96 (87–99) | 67 (52–80) | 15.7 | 91 | 82 |

| POCT ACT+ ≤130 s | <100 | 96 (85–99) | 68 (55–78) | 16.2 | 96 | 68 |

n = 118 samples

Sensitivity and specificity are provided with 95% confidence intervals

ACT+ activated clotting time plus, LR likelihood ratio, NPV negative predictive value, POCT point of care test, PPV positive predictive value, PT prothrombin time

Table 3.

Diagnostic accuracy of Hemochron® Signature POCT for dabigatran

| Coagulation test result | Threshold (ng/mL) | Specificity (%) | Sensitivity (%) | LR | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POCT PT ≤1.1 | <30 | 99 (92–100) | 47 (37–58) | 34.6 | 98 | 59 |

| POCT PT ≤1.2 | <50 | 98 (88–100) | 66 (56–74) | 33.5 | 99 | 56 |

| POCT ACT+ ≤100 s | <30 | 96 (87–99) | 36 (26–47) | 8.7 | 92 | 54 |

| POCT ACT+ ≤100 s | <50 | 98 (88–100) | 31 (23–40) | 15.7 | 97 | 61 |

n = 168 samples

Sensitivity and specificity are provided with 95% confidence intervals

ACT+ activated clotting time plus, LR likelihood ratio, NPV negative predictive value, POCT point of care test, PPV positive predictive value, PT prothrombin time

Rivaroxaban concentrations at <30 and <100 ng/mL were detected with >95% specificity at PT/INR POCT ≤1.0 and ≤1.1 and ACT+ POCT ≤120 and ≤130 s. Dabigatran concentrations at <30 and <50 ng/mL were detected with >95% specificity at PT/INR POCT ≤1.1 and ≤1.2 and ACT+ POCT ≤100 s (for both thresholds). Likelihood ratio (LR) was highest for rivaroxaban and ACT+ POCT (<30 ng/mL, LR 15.7; <100 ng/mL, LR 16.2), and dabigatran and PT POCT (<30 ng/mL, LR 34.6; <50 ng/mL, LR 33.5).

Performance of laboratory-based DOAC-specific coagulation assays

The calibrated anti-Xa assay (Chromogenix COAMATIC Heparin Test) showed the highest correlation to rivaroxaban levels of all evaluated coagulation tests (r = 0.94, p < 0.001). Test results predicted rivaroxaban concentrations <30 and <100 ng/mL with a respective specificity of 99% and 92%, and a sensitivity of 98% and 97%.

Correlation between dTT (Hemoclot) and dabigatran concentrations was also very strong (r = 0.86, p < 0.001). Test results predicted dabigatran concentrations <30 and <50 ng/mL with a respective specificity of 95% and 84%, and a sensitivity of 77% and 82%.

Discussion

Summary

Results of Hemochron® Signature coagulation POCT correlate with rivaroxaban and dabigatran, but not with apixaban concentrations. PT/INR and ACT+ test cards are of particular interest, as they are influenced by both rivaroxaban and dabigatran. POCT-specific cut-offs can be used to exclude relevant rivaroxaban and dabigatran concentrations (Table 1) at the bedside with high specificity.

Concentration thresholds

Data on what constitutes a relevant DOAC concentration, i.e. a concentration that leads to clinically significant coagulation impairment, are scarce. Current guidelines are predominantly time-based. Urgent surgical procedures may be performed at trough [9, 17], i.e. 12 or 24 h after last intake of apixaban/dabigatran [18, 19] or rivaroxaban [20], respectively. Thrombolysis for ischaemic stroke can be performed >48 h after the last intake of any DOAC [21]. However, significant DOAC concentrations have been observed in patients even beyond 48 h after the last intake [22]. Hence, the usefulness of time-based guidelines is limited. Furthermore, obtaining information on last DOAC intake might be impossible in patients with stroke and aphasia or dementia.

Specific concentration thresholds that increase bleeding risk can currently only be estimated based on retrospective analyses [10], pharmacodynamic considerations [11], and expert opinions [12, 14]. For surgical procedures, concentrations of rivaroxaban <30 ng/mL [10], and dabigatran <30 [10], <48 [11], and <50 ng/mL [12] have been proposed as safe. For apixaban, such concentration thresholds are currently unknown [13]. For acute ischaemic stroke, DOAC concentrations that may permit thrombolysis have been suggested by an expert group (see Table 1) [14]. It should be noted that these latter concentrations represent an expert opinion rather than quantitatively determined values.

Following these recommendations, we based our analysis on the concentrations proposed as safe for surgery [9–12] and the concentrations that may permit thrombolysis in ischaemic stroke [14].

Coagulation testing for rivaroxaban and dabigatran

Quantification of DOAC concentrations using DOAC-specific assays is the recommended clinical standard for coagulation testing during DOAC treatment, i.e. anti-Xa activity for rivaroxaban and dTT or ecarin-based assays for dabigatran [17, 23]. Our study confirms that these assays provide high diagnostic accuracy for all tested DOAC. However, we found that Hemoclot had limited specificity and sensitivity for dabigatran concentrations <50 ng/mL, a threshold considered safe for surgery [11, 12] and thrombolysis [14]. At such low dabigatran concentrations, the reduced accuracy of Hemoclot has also been reported by others [24].

In many institutions, availability of DOAC-specific coagulation assays is limited [25]. For this reason, several authors have argued that unspecific global coagulation assays might suffice to rule out relevant DOAC concentrations [14, 26, 27].

Prompt availability and instantaneous results makes coagulation POCT an attractive option in emergency situations. We have previously shown that relevant concentrations of rivaroxaban can be qualitatively ruled out with CoaguChek®, a POCT designed for VKA monitoring [2]. The results of our current trial suggest Hemochron® Signature as a more versatile alternative: while CoaguChek® was only responsive to rivaroxaban, results of Hemochron® Signature PT/INR and ACT+ test cards were altered by both rivaroxaban and dabigatran.

Interestingly, the two factor Xa inhibitors, rivaroxaban and apixaban, differed in their effects on Hemochron® Signature POCT results. While POCT results at different apixaban concentrations were almost randomly distributed (Fig. 1), a strong correlation was found for rivaroxaban. Similar findings have been previously reported by our group and others for POCT and laboratory-based assays [2, 28]. To our knowledge, no convincing explanation for this difference has yet been provided.

Irregularities of Hemochron® Signature POCT results in the presence of dabigatran were noted early [4]. Recently, three trials evaluated this POCT (or the equivalent GEM® PCL Plus) for coagulation monitoring in patients treated with rivaroxaban [6], dabigatran [5], or both [7]. These studies reported that, in the case of low DOAC concentrations, coagulation test results frequently fell into a “normal range” previously established in untreated volunteers and concluded that the device cannot sufficiently distinguish between patients at trough concentrations and untreated patients [5–7]. We contest the usefulness of a “normal range” found in untreated volunteers for the monitoring of DOAC. In agreement with the previous reports, we observed that the alterations in coagulation results in the presence of DOAC often did not exceed values found in untreated patients. Nevertheless, our analyses show that POCT results below DOAC-specific cut-offs are highly predictive when used to qualitatively rule out relevant concentrations of rivaroxaban and dabigatran.

Translation into the real world

According to the results of this study, Hemochron® Signature can be used to qualitatively rule out relevant concentrations of rivaroxaban and dabigatran during DOAC therapy, and accurately identify patients who are safe for surgery or thrombolysis. To ensure patient safety, we chose to establish cut-off values that provide >95% specificity. Although this limits the sensitivity of our results (i.e. not all eligible patients are identified), our approach allows the rapid identification of a relevant fraction of patients that can be treated immediately without the need to await the results of much slower laboratory-based tests (Figs. 3 and 4). For example, out of the 118 rivaroxaban samples included in this study, a Hemochron® Signature ACT+ test result ≤1.2 identified 34 samples as eligible for treatment based on a rivaroxaban threshold <30 ng/ml (Fig. 4). Out of these 34 samples, 31 were identified correctly (true positives, PPV 91%), demonstrating the high diagnostic accuracy. However, the limited sensitivity of our approach resulted in 15 samples that were not identified as eligible despite containing <30 ng/ml rivaroxaban (false negatives, NPV 82%).

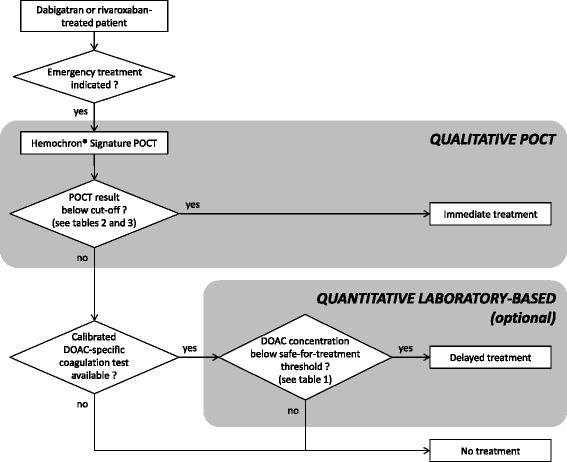

Fig. 3.

Proposed algorithm for emergency coagulation assessment in rivaroxaban- and dabigatran-treated patients. DOAC direct oral anticoagulant, POCT point-of-care test

Fig. 4.

Scatter plot of rivaroxaban concentrations (green area: <30 ng/mL) and activated clotting time (ACT+) POCT illustrating the diagnostic accuracy of POCT results. Green diamonds represent samples below the safe-for-treatment threshold that are correctly identified as eligible for immediate treatment (true positive). Blue crosses represent samples that are not detected although containing concentrations below the safe-for-treatment threshold (false negative). These can potentially still receive delayed treatment if slower laboratory-based DOAC-specific tests are available. Green crosses represent samples above the POCT cut-off correctly identified as not eligible for treatment (true negative). Red diamonds represent the few samples incorrectly identified as eligible for treatment despite concentrations above the safe-for-treatment threshold (false positive)

Although both rivaroxaban and dabigatran can be detected with PT/INR or ACT+ POCT, our likelihood ratio calculations support the use of ACT+ test cards for rivaroxaban and PT/INR test cards for dabigatran.

Importantly, since there is no single POCT cut-off value that can safely rule out all DOAC, knowledge of the patient’s medication history is necessary. Furthermore, the blood concentration of all DOAC increase rapidly after intake. Therefore, coagulation results obtained within the first 4 h after intake are not reliable.

Strengths and limitations

Our study adds considerable insight to previous reports. We are the first to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of Hemochron® Signature to qualitatively rule out relevant DOAC concentrations of apixaban, rivaroxaban, and dabigatran. To the best of our knowledge, apixaban has never been tested with this device before. In a departure from previous studies, we aimed at establishing DOAC-specific cut-offs to provide clinicians with a practical tool for decision making during emergency treatment. All samples were acquired from real-life patients, avoiding the use of spiked plasma. Primarily collecting samples during treatment initiation rather than a steady state provided a high number of samples containing very low DOAC concentrations. Compared to previous studies [5–7], this allowed superior assessment of how such low concentrations influence coagulation assays. Due to low dabigatran concentrations in samples collected during treatment initiation, we decided to include samples from eight patients on maintenance therapy. Although this adds heterogeneity to our patient population, we did not find differences in correlation to POCT results between the two groups. Six sequential samples were acquired from each patient. Hence, a bias due to repeated measurements in individual patients cannot be excluded but this approach allowed us to cover a wide spectrum of DOAC concentrations. Due to the use of venous blood in this study, our results cannot be extended to test results obtained from capillary samples. However, as venous access is routinely obtained in all emergency patients we do not expect this to limit the clinical applicability of our results.

What constitutes a clinically relevant DOAC concentration is a matter for debate, and the concentration thresholds investigated in our study, albeit based on current literature, have not been confirmed by prospective clinical trials. Furthermore, generalizability of our results is limited by the single-centre nature of our trial. For these reasons, validation of our data is warranted, ideally including clinical outcome-oriented end-points.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that Hemochron® Signature POCT in combination with PT/INR or ACT+ test cards can be used to qualitatively rule out relevant concentrations of rivaroxaban and dabigatran, but not of apixaban.

Thus, Hemochron® Signature POCT can be a fast and reliable alternative for guiding emergency treatment during rivaroxaban and dabigatran therapy. It allows the rapid identification of a relevant fraction of patients that can be treated immediately without the need to await the results of much slower laboratory-based coagulation tests. The high clinical relevance of this question warrants a large-scale trial to investigate the clinical safety of this approach.

Acknowledgments

We thank Louise Härtig for language revision of the manuscript. We acknowledge support from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the Open Access Publishing Fund of the University of Tübingen.

Funding

No financial support. One Hemochron® Signature Elite device was allocated by Keller Medical GmbH (Bad Soden/Taunus, Germany) for research purposes. The company had no influence whatsoever on patient enrolment, acquisition of data, interpretation of data, or drafting the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional file.

Authors’ contributions

ME and SP designed the study, participated in enrolment and data acquisition, and headed preparation of the manuscript. CS and FH enrolled patients and performed POCT at the bedside. IB, AP, and JK conducted all laboratory-based coagulation tests and UPLC-MS. GB assisted with statistical data analyses. CSZ, UZ, and FH helped with patient recruitment and supervised the preparation of the manuscript. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

SP received speaker’s honoraria and consulting honoraria from Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer, and Daiichi Sankyo, and reimbursement for congress traveling and accommodation from Bayer and Boehringer-Ingelheim. ME and FH received reimbursement for congress traveling and accommodation from Bayer. IB received speaker’s honoraria and reimbursement for congress traveling from Bristol-Myers Squibb and CSL Behring. UZ received research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer and speaker’s honoraria and reimbursement for congress traveling and accommodation from Biogen Idec and Medtronic. The remaining authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from the ethics committee of Tübingen University Hospital (protocol no. 259/2013BO1; additional patients receiving dabigatran were enrolled using protocol no. 270/2015B01). The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to enrolment.

Abbreviations

- ACT

Activated clotting time

- ACT+

Activated clotting time plus

- ACT-LR

Activated clotting time-low range

- aPTT

Activated partial thromboplastin time

- DOAC

Direct oral anticoagulants

- dTT

Diluted thrombin time

- IQR

Interquartile range

- LR

Likelihood ratio

- NPV

Negative predictive value

- POCT

Point-of-care testing

- PPV

Positive predictive value

- PT/INR

Prothrombin time/international normalized ratio

- UPLC-MS

Ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry

- VKA

Vitamin K antagonists

Additional file

Patient characteristics in the study groups. Table S2. Baseline laboratory results of patients in the study groups. Table S3. Diagnostic accuracy of Hemochron® Signature aPTT and ACT-LR POCT cards for dabigatran. (DOC 87 kb)

Contributor Information

Matthias Ebner, Email: matthias.ebner@charite.de.

Ingvild Birschmann, Email: ibirschmann@hdz-nrw.de.

Andreas Peter, Email: andreas.peter@med.uni-tuebingen.de.

Charlotte Spencer, Email: charlyspenc@aol.com.

Florian Härtig, Email: florian.haertig@med.uni-tuebingen.de.

Joachim Kuhn, Email: jkuhn@hdz-nrw.de.

Gunnar Blumenstock, Email: gunnar.blumenstock@med.uni-tuebingen.de.

Christine S. Zuern, Email: christine.meyer-zuern@med.uni-tuebingen.de

Ulf Ziemann, Email: ulf.ziemann@uni-tuebingen.de.

Sven Poli, Phone: +491724682284, Email: sven.poli@uni-tuebingen.de.

References

- 1.Rizos T, Herweh C, Jenetzky E, Lichy C, Ringleb PA, Hacke W, Veltkamp R. Point-of-care international normalized ratio testing accelerates thrombolysis in patients with acute ischemic stroke using oral anticoagulants. Stroke. 2009;40(11):3547–51. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.562769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ebner M, Peter A, Spencer C, Hartig F, Birschmann I, Kuhn J, Wolf M, Winter N, Russo F, Zuern CS, et al. Point-of-care testing of coagulation in patients treated with non-vitamin k antagonist oral anticoagulants. Stroke. 2015;46(10):2741–7. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baruch L, Sherman O. Potential inaccuracy of point-of-care INR in dabigatran-treated patients. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45(7–8):e40. doi: 10.1345/aph.1Q105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Ryn J, Baruch L, Clemens A. Interpretation of point-of-care INR results in patients treated with dabigatran. Am J Med. 2012;125(4):417–20. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawes EM, Deal AM, Funk-Adcock D, Gosselin R, Jeanneret C, Cook AM, Taylor JM, Whinna HC, Winkler AM, Moll S. Performance of coagulation tests in patients on therapeutic doses of dabigatran: a cross-sectional pharmacodynamic study based on peak and trough plasma levels. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11(8):1493–502. doi: 10.1111/jth.12308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Francart SJ, Hawes EM, Deal AM, Adcock DM, Gosselin R, Jeanneret C, Friedman KD, Moll S. Performance of coagulation tests in patients on therapeutic doses of rivaroxaban. A cross-sectional pharmacodynamic study based on peak and trough plasma levels. Thromb Haemost. 2014;111(6):1133–40. doi: 10.1160/TH13-10-0871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mani H, Herth N, Kasper A, Wendt T, Schuettfort G, Weil Y, Pfeilschifter W, Linnemann B, Herrmann E, Lindhoff-Last E. Point-of-care coagulation testing for assessment of the pharmacodynamic anticoagulant effect of direct oral anticoagulant. Ther Drug Monit. 2014;36(5):624–31. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0000000000000064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuhn J, Gripp T, Flieder T, Dittrich M, Hendig D, Busse J, Knabbe C, Birschmann I. UPLC-MRM mass spectrometry method for measurement of the coagulation inhibitors dabigatran and rivaroxaban in human plasma and its comparison with functional assays. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0145478. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dincq AS, Lessire S, Douxfils J, Dogne JM, Gourdin M, Mullier F. Management of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in the perioperative setting. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:385014. doi: 10.1155/2014/385014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pernod G, Albaladejo P, Godier A, Samama CM, Susen S, Gruel Y, Blais N, Fontana P, Cohen A, Llau JV, et al. Management of major bleeding complications and emergency surgery in patients on long-term treatment with direct oral anticoagulants, thrombin or factor-Xa inhibitors: proposals of the working group on perioperative haemostasis (GIHP)—March 2013. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;106(6–7):382–93. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.CHMP assessment report Pradaxa. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Assessment_Report_-_Variation/human/000829/WC500110875.pdf. Accessed 16 Jan 2017.

- 12.Eikelboom JW, Weitz JI. Dabigatran monitoring made simple? Thromb Haemost. 2013;110(3):393–5. doi: 10.1160/TH13-07-0576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ward C, Conner G, Donnan G, Gallus A, McRae S. Practical management of patients on apixaban: a consensus guide. Thromb J. 2013;11(1):27. doi: 10.1186/1477-9560-11-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steiner T, Bohm M, Dichgans M, Diener HC, Ell C, Endres M, Epple C, Grond M, Laufs U, Nickenig G, et al. Recommendations for the emergency management of complications associated with the new direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), apixaban, dabigatran and rivaroxaban. Clin Res Cardiol. 2013;102(6):399–412. doi: 10.1007/s00392-013-0560-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vassarstats: Website for Statistical Computation. http://vassarstats.net/clin1.html. Accessed 16 Jan 2017.

- 16.Evans JD. Straightforward statistics for the behavioral sciences. Pacific Grove: Brooks/Cole Publ. Co., an International Thomson Publ. Co.; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heidbuchel H, Verhamme P, Alings M, Antz M, Hacke W, Oldgren J, Sinnaeve P, Camm AJ, Kirchhof P, European Heart Rhythm Association European Heart Rhythm Association Practical Guide on the use of new oral anticoagulants in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2013;15:625–51. doi: 10.1093/europace/eut083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eliquis, INN-apixaban: Summary of Product Characteristics. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002148/WC500107728.pdf. Accessed 16 Jan 2017.

- 19.Pradaxa, INN-dabigatran: Summary of Product Characteristics. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000829/WC500041059.pdf. Accessed 16 Jan 2017.

- 20.Mueck W, Lensing AW, Agnelli G, Decousus H, Prandoni P, Misselwitz F. Rivaroxaban: population pharmacokinetic analyses in patients treated for acute deep-vein thrombosis and exposure simulations in patients with atrial fibrillation treated for stroke prevention. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2011;50(10):675–86. doi: 10.2165/11595320-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jauch EC, Saver JL, Adams HP, Jr, Bruno A, Connors JJ, Demaerschalk BM, Khatri P, McMullan PW, Jr, Qureshi AI, Rosenfield K, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44(3):870–947. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e318284056a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Godier A, Martin AC, Leblanc I, Mazoyer E, Horellou MH, Ibrahim F, Flaujac C, Golmard JL, Rosencher N, Gouin-Thibault I. Peri-procedural management of dabigatran and rivaroxaban: duration of anticoagulant discontinuation and drug concentrations. Thromb Res. 2015;136(4):763–8. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cuker A, Siegal DM, Crowther MA, Garcia DA. Laboratory measurement of the anticoagulant activity of the non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(11):1128–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.05.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stangier J, Feuring M. Using the HEMOCLOT direct thrombin inhibitor assay to determine plasma concentrations of dabigatran. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2012;23(2):138–43. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e32834f1b0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tripodi A. The laboratory and the direct oral anticoagulants. Blood. 2013;121(20):4032–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-12-453076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siegal DM, Crowther MA. Acute management of bleeding in patients on novel oral anticoagulants. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(7):489–498b. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tran H, Joseph J, Young L, McRae S, Curnow J, Nandurkar H, Wood P, McLintock C. New oral anticoagulants: a practical guide on prescription, laboratory testing and peri-procedural/bleeding management. Intern Med J. 2014;44(6):525–36. doi: 10.1111/imj.12448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Douxfils J, Tamigniau A, Chatelain B, Goffinet C, Dogne JM, Mullier F. Measurement of non-VKA oral anticoagulants versus classic ones: the appropriate use of hemostasis assays. Thromb J. 2014;12:24. doi: 10.1186/1477-9560-12-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional file.