Participants of expert group on CPG for Depression

Gautam Saha, I.D Gupta, Navendu Gaur, Tushar Jagawat, Anita Gautam, T. S Sathyanarayana Rao

INTRODUCTION

Depression is a common disorder, which often leads to poor quality of life and impaired role functioning. It is known to be a major contributor to the global burden of diseases and according to World Health Organization (WHO), depression is the fourth leading cause of disability worldwide and it is projected that by 2020, it will be the second most common leading cause of disability. Depression is also associated with high rates of suicidal behaviour and mortality. When depression occurs in the context of medical morbidity, it is associated with increased health care cost, longer duration of hospitalization, poor cooperation in treatment, poor treatment compliance and high rates of morbidity. Depression is also known to be associated with difficulties in role transitions (e.g., low education, high teen child-bearing, marital disruption, unstable employment) and poor role functioning (e.g., low marital quality, low work performance, low earnings). It is also reported to be a risk factor for the onset and persistence of a wide range of secondary disorders. Available data also suggests that between one-third and one-half of patients also experience recurrence of depressive episodes.

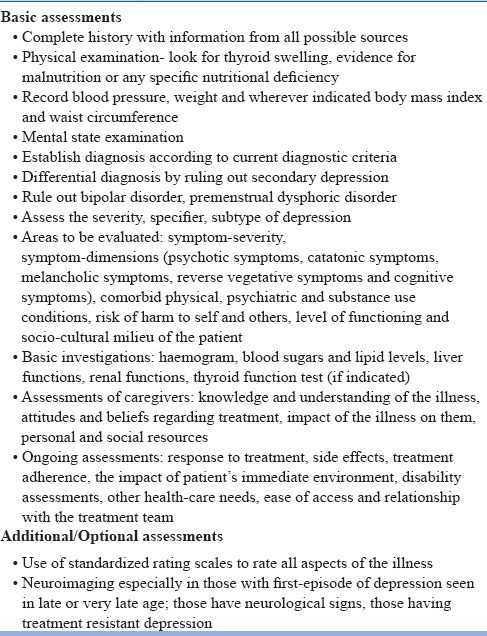

ASSESSMENT AND EVALUATION (table-1)

Table 1.

Components of assessment and evaluation

Management of depression involves comprehensive assessment and proper establishment of diagnosis. The assessment must be based on detailed history, physical examination and mental state examinations. History must be obtained from all sources, especially the family. The diagnosis must be recorded as per the current diagnostic criteria.

Depression often presents with a combination of symptoms of depressed mood, loss of interest or pleasure, decreased energy and fatigue, reduced concentration and attention, reduced self-esteem and self-confidence, ideas of guilt and unworthiness, bleak and pessimistic views of the future, ideas or acts of self-harm or suicide, disturbed sleep and diminished appetite. Depending on the severity of depression some of these symptoms may be more marked and develop characteristic features that are widely regarded as having special clinical significance. These symptoms are known as somatic symptoms of depression and include symptoms of loss of interest or pleasure in activities that are normally enjoyable, lack of emotional reactivity to normally pleasurable surroundings and events, waking up in the morning 2 hours or more before the usual time, depression worse in the morning, objective evidence of definite psychomotor retardation or agitation (remarked on or reported by other people), marked loss of appetite, weight loss (often defined as 5% or more of body weight in the past month) and marked loss of libido. It is important to note that for the diagnosis of depressive disorder these symptoms need to be present for at least 2 weeks and need to be associated with psychosocial dysfunction.

Some of the patients with depression may present with predominant complaints of aches, pains and fatigue and they may not report sadness of mood on their own. A careful evaluation of these patients often reveals the underlying features of depression. However, it is important to note that many patients with depression will also have associated anxiety symptoms. With increasing severity of depression patients may report psychotic symptoms and may also present with catatonic features. Thorough assessment also ought to focus on evaluation for comorbid substance abuse/dependence. Careful history of substance intake need to be taken to evaluate the relationship of depression with substance intoxication, withdrawal and abstinence. Whenever required appropriate tests like, urine or blood screens (with prior consent) may be used to confirm the existence of comorbid substance abuse/dependence.

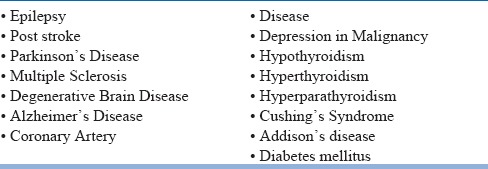

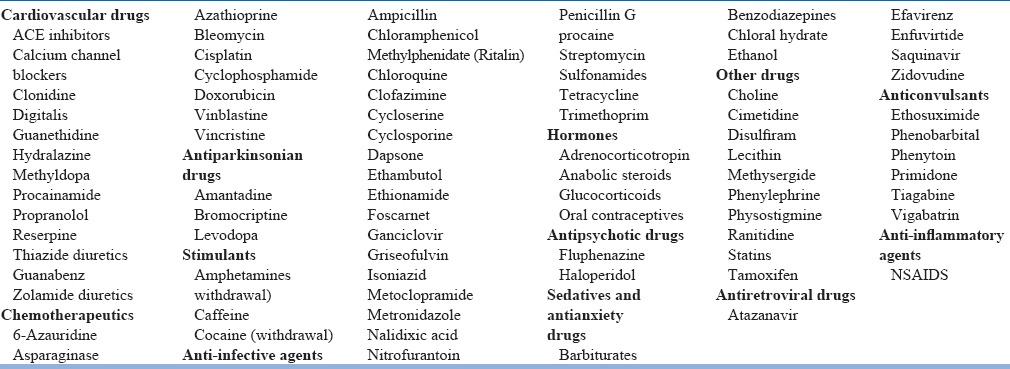

Many physical illnesses are known to have high rates of depression. In some situations the physical illnesses have causative role in development of depression, whereas in other situations the relationship/co-occurrence is due to common etiology. Some of the physical illnesses commonly associated with depression are listed in Table-2. When depression occurs in relation to physical illness attempt may be made to clearly delineate the symptoms of depression and physical illness. Further, while making the diagnosis, it maybe clearly mentioned as to which diagnostic approach [i.e., inclusive approach (symptoms are counted whether or not they might be attributable to physical illness), substitute approach (nonsomatic symptoms are substituted with somatic symptoms), exclusive approach (somatic symptoms are deleted from the diagnostic criteria) or best estimate approach] was followed. Further, while reviewing the treatment history of medical illnesses, medication induced depression must be kept in mind, as many medications are known to cause depression (Table-3).

Table 2.

Some of the physical illnesses commonly associated with depression

Table 3.

Medications known to cause depression

It is always important to take the longitudinal life course perspective into account to evaluate for previous episodes and presence of symptoms of depression amounting to dysthymia. Evaluation of history also takes into consideration the relationship of onset of depression with change in season (seasonal affective disorder), peripartum period and phase of menstrual cycle. Further, the longitudinal course approach may also take into account response to previous treatment and whether the patient achieved full remission, partial remission and did not respond to treatment.

An important aspect of diagnosis of depression is to rule out bipolar disorder. Many patients with bipolar disorder present to the clinicians during the depressive phase of illness and spontaneously do not report about previous hypomanic or manic episodes. Careful history from the patient and other sources (family members) often provide important clues for the bipolar disorder. It is often useful to use standardized scales like mood disorder questionnaire to rule out bipolarity. Treating a patient of bipolar depression as unipolar disorder can increase the risk of antidepressant induced switch. Presence of psychotic features, marked psychomotor retardation, reverse neurovegetative symptoms (excessive sleep and appetite), irritability of mood, anger, family history of bipolar disorder and early age of onset need to alert the clinicians to evaluate for the possibility of bipolar disorder, before concluding that they are dealing with unipolar depression.

Area to be covered in assessment include symptom dimensions, symptom-severity, comorbid psychiatric and medical conditions, particularly comorbid substance abuse, the risk of harm to self or others, level of functioning and the socio-cultural milieu of the patient.

In case patient has received treatment in the past, it is important to evaluate the information in the form of type of antidepressant used, dose of medication used, compliance with medication, reasons for poor compliance, reasons for discontinuation of medication, response to treatment, side effects experienced etc. If the medications were changed, then the reason for change is also to be evaluated.

Wherever possible, unstructured assessments need to be supplemented by ratings on appropriate standardized rating scales. Depending on the need, investigations need to be carried out. The use of neuroimaging may be indicated in those with first-episode of depression seen in late or very late age; those have neurological signs, those having treatment resistant depression.

Besides, patients, information about the illness need to be obtained from the caregivers too and their knowledge and understanding of the illness, their attitudes and beliefs regarding treatment, the impact of the illness on them and their personal and social resources need to be evaluated.

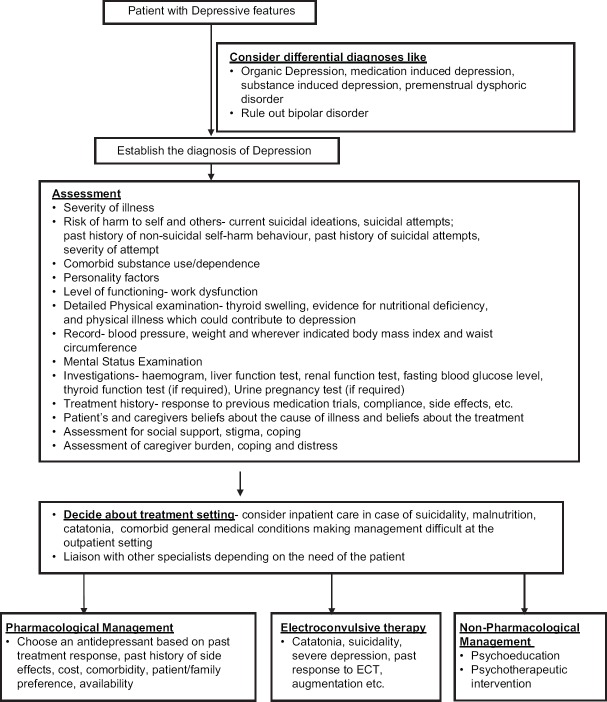

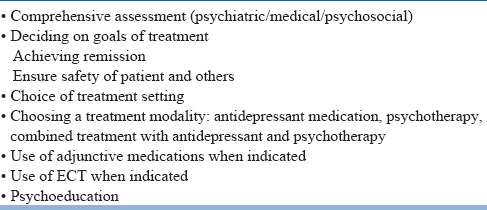

FORMULATING A TREATMENT PLAN (FIGURE-1)

Figure 1.

Initial evaluation and management plan for Depression

Formulation of treatment plan involves deciding about treatment setting, medications and psychological treatments to be used. Patients and caregivers may be actively consulted while preparing the treatment plan. A practical, feasible and flexible treatment plan can be formulated to address the needs of the patients and caregivers. Further the treatment plan can be continuously re-evaluated and modified as required.

EVALUATE THE SAFETY OF PATIENT AND OTHERS

A careful assessment of the patient's risk for suicide should be done. During history inquiry for the presence of suicidal ideation and other associated factors like presence of psychotic symptoms, severe anxiety, panic attacks and alcohol or substance abuse which increases the risk of suicide need to be evaluated. It has been found that severity of depressive symptomatology is a strong predictor of suicidal ideation over time in elderly patients. Evaluation also includes history of past suicide attempts including the nature of those attempts. Patients also need to be asked about suicide in their family history. During the mental status examinations besides enquiring about the suicidal ideations, it is also important to enquire about the degree to which the patient intends to act on the suicidal ideation and the extent to which the patient has made plans or begun to prepare for suicide. The availability of means for suicide be inquired about and a judgment may be made concerning the lethality of those means. Patients who are found to possess suicidal or homicidal ideation, intention or plans require close monitoring. Measures such as hospitalization may be considered for those at significant risk.

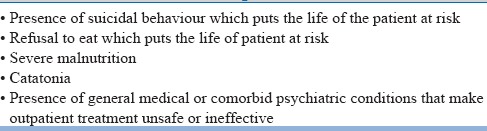

CHOICE OF TREATMENT SETTINGS

Majority of the cases of depression seen in the clinical setting are of mild to moderate severity and can be managed at the outpatient setting. However, some patients have severe depression which may be further associated with psychotic symptoms, catatonic symptoms, poor physical health status, suicidal or homicidal behaviour etc. In such cases, careful evaluation is to be done to decide about the treatment setting and whenever necessary inpatient care may be offered. In general, the rule of thumb is that the patients may be treated in the setting that is most safe and effective. Severely ill patients who lack adequate social support outside of a hospital setting may be considered for admission to a hospital whenever feasible. The optimal treatment setting and the patient's ability to benefit from a different level of care may be re-evaluated on an ongoing basis throughout the course of treatment. Some of the common indications for inpatient care are shown in Table-4.

Table 4.

Some indications for inpatient care during acute episodes

All inpatients should have accompanying family caregivers. In case inpatient care facilities are not available, than the patient and/or family need to be informed about such a need and admission in nearest available inpatient facility can be facilitated.

THERAPEUTIC ALLIANCE

Irrespective of the treatment modalities selected for patients, it is important for the psychiatrist to establish a therapeutic alliance with the patient. A strong treatment alliance between patient and psychiatrist is crucial for poorly motivated, pessimistic depressed patient who are sensitive to side effect of medications. A positive therapeutic alliance always generates hope for good outcome.

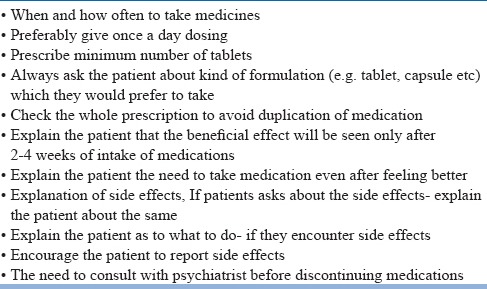

ENHANCED TREATMENT COMPLIANCE

The successful treatment of major depressive disorder requires adequate compliance to treatment plan. Patients with depressive disorder may be poorly motivated and unduly pessimistic over their chances of recovery with treatment. In addition, the side effect or requirements of treatment may lead to non-adherence. Patients are to be encouraged to articulate any concern regarding adherence and clinicians need to emphasize the importance of adherence for successful treatment. Simple measures which can help in improving the compliance are given in table-5.

Table 5.

Measures which can improve medication compliance

ADDRESS EARLY SIGNS OF RELAPSE

Many patients with depression experience relapse. Accordingly, patients as well as their families if appropriate may be educated about the risk of relapse. They can be educated to identify early signs and symptoms of new episodes. Patients can also be asked to seek adequate treatment as early in the course of a new episode as possible to decrease the likelihood of a full-blown relapse or complication.

TREATMENT OPTIONS FOR MANAGEMENT FOR DEPRESSION

Treatment options for management of depression can be broadly be divided into antidepressants, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and psychosocial interventions. Other less commonly used treatment or treatments used in patients with treatment resistant depression include repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), light therapy, transcranial direct stimulation, vagal nerve stimulation, deep brain stimulation and sleep deprivation treatment. In many cases benzodiazepines are used as adjunctive treatment, especially during the initial phase of treatment. Additionally in some cases, lithium and thyroid supplements may be used as an augmenting agent when patient is not responding to antidepressants.

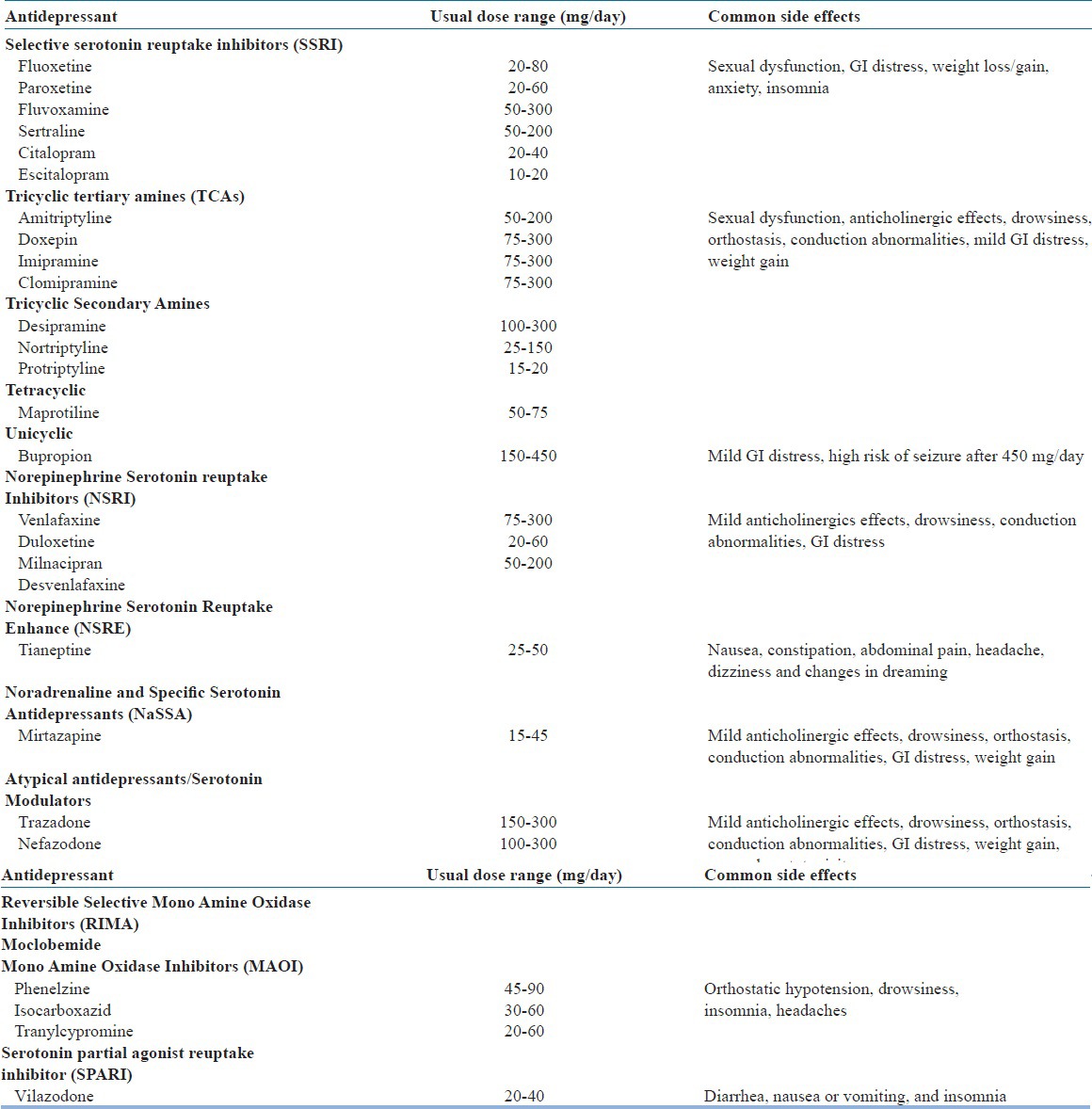

Antidepressants

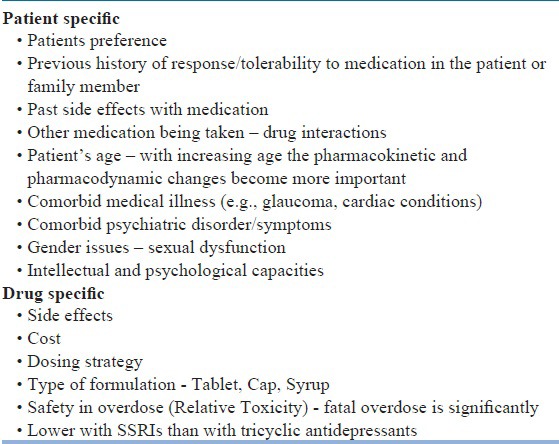

Large numbers of antidepressants (Table-6) are available for management of depression and in general all the antidepressants have been shown to have nearly equal efficacy in the management of depression. Antidepressant medication may be used as initial treatment modality for patients with mild, moderate, or severe depressive episode. The selection of antidepressant medications may be based on patient specific and drug specific factors, as given in Table-7. In general, because of the side effect and safety profile, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are considered to be the first line antidepressants. Other preferred options include tricyclic antidepressants, mirtazapine, bupropion, and venlafaxine. Usually the medication must be started in the lower doses and the doses must be titrated, depending on the response and the side effects experienced.

Table 6.

Antidepressants Armamentarium

Table 7.

Factors that determine the selection of Antidepressant Drug

Dose and duration of antidepressants

Patients who have started taking an antidepressant medication should be carefully monitored to assess the response to pharmacotherapy as well as the emergence of side effects and safety. Factors to consider when determining the frequency of monitoring include severity of illness, patient's co-operation with treatment, the availability of social support and the presence of comorbid general medical problems. Visits may be kept frequent enough to monitor and address suicidality and to promote treatment adherence. Improvement with pharmacotherapy can be observed after 4-6 weeks of treatment. If at least a moderate improvement is not observed in this time period, reappraisal and adjustment of the pharmacotherapy should be considered.

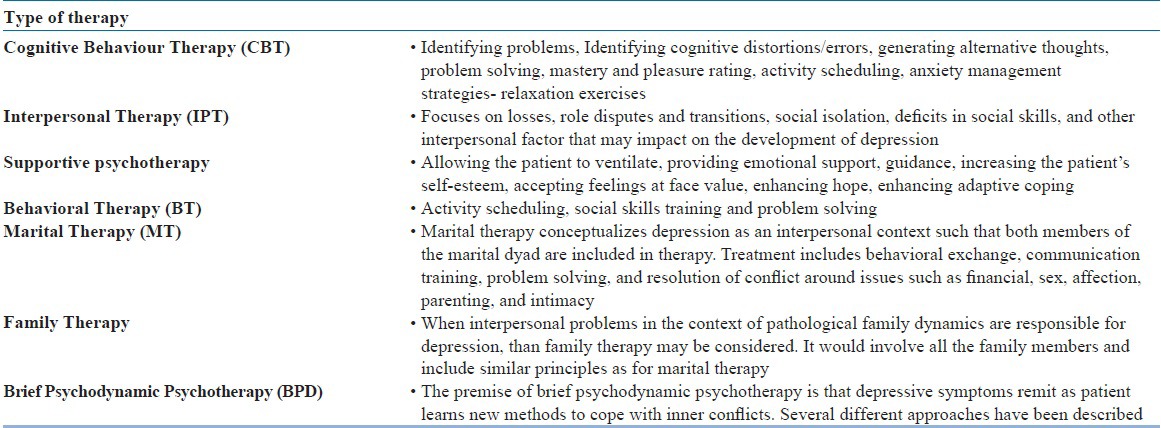

Psychotherapeutic interventions

A specific, effective psychotherapy may be considered as an initial treatment modality for patients with mild to moderate depressive disorder. Clinical features that may suggest the use of a specific psychotherapy include the presence of significant psychosocial stressors, intrapsychic conflict and interpersonal difficulties. Patient's preference for psychotherapeutic approaches is an important factor that may be considered in the decision to use psychotherapy as the initial treatment modality. Pregnancy, lactation, orthe wish to become pregnant may also be an indication for psychotherapy as an initial treatment. Various psychotherapeutic interventions which may be considered based on feasibility, expertise available and affordability are shown in Table-8.

Table 8.

Psychotherapeutic interventions for Depression

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and interpersonal therapy are the psychotherapeutic approaches that have the best documented efficacy in the literature for management of depression. When psychodynamic psychotherapy is used as specific treatment, in addition to symptom relief it is frequently with broader long term goals.

The psychiatrist should take into account multiple factors when determining the frequency of sessions for individual patients, including the specific type and goals of psychotherapy, the frequency necessary to create and maintain a therapeutic relationship, the frequency of visits required to ensure treatment adherence, and the frequency necessary to monitor and address suicidality. The frequency of outpatient visits during the acute phase generally varies from once a week in routine cases to as often as several times a week. Regardless of the type of psychotherapy selected, the patient's response to treatment should be carefully monitored. For a given patient, time spent and frequency of visit may be decided by the psychiatrist.

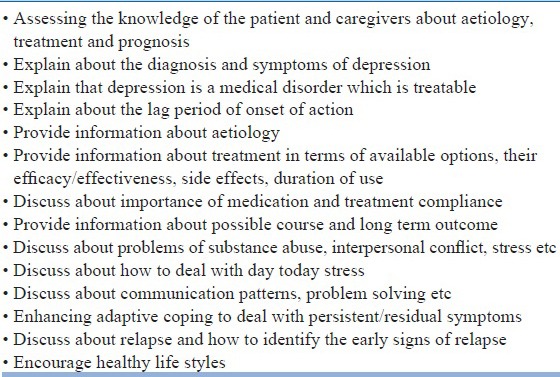

Psychoeducation to the patient and, when appropriate, to the family

Education concerning depression and its treatments can be provided to all patients. When appropriate, education can also be provided to involved family members. Specific educational elements may be helpful in some circumstances, e.g. that depression is a real illness and that effective treatments are both necessary and available may be crucial for patients who attribute their illness to a moral defect or witch craft. Education regarding available treatment options will help patients make informed decisions, anticipate side effects and adhere to treatments. Another important aspect of providing education is informing the patient and especially family about the lag period of onset of action of antidepressants. Important components of psychoeducation are given in Table-9.

Table 9.

Basic components of Psychoeducation

Combination of pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy

There is class of patients who may require the combination of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. In general, the same issues that influence the choice of medication or psychotherapy when used alone should be considered when choosing treatments for patients receiving combined therapy.

PHASES OF ILLNESS/TREATMENT

Management of depression can be broadly divided into three phases, i.e., acute phase, continuation phase and maintenance phase. Maintenance phase of treatment is usually considered when patient has recurrent depressive disorder.

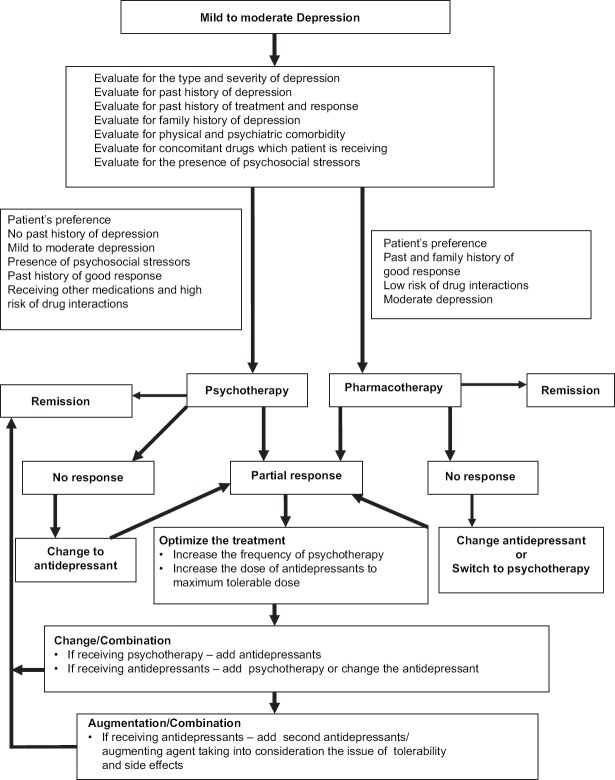

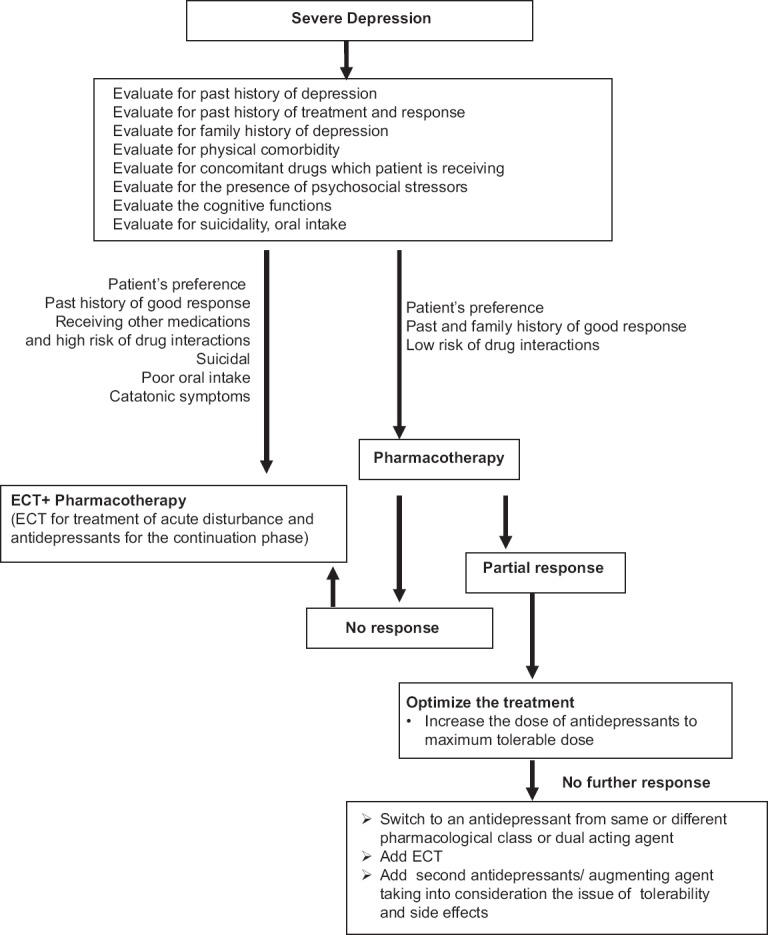

ACUTE PHASE TREATMENT

The goal of acute phase treatment is to achieve remission, as presence of residual symptoms increase the risk of chronic depression, poor quality of life and also impairs recovery from physical illness. Treatment generally results in improvement in quality of life and better functional capacity. The various components of acute phase treatment are shown in Table-10 and the treatment algorithm is shown in figure-2 and 3.

Table 10.

Management in the acute phase

Figure 2.

Treatment algorithm of mild to moderate Depression

Figure 3.

Treatment algorithm of Severe Depression

In acute phase psychiatrist may choose between several initial treatment modalities, including pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, the combination of medication and psychotherapy, or ECT. Selection of an initial treatment modality is usually influenced by both clinical (e.g. severity of symptoms) and other factors (e.g. patient preference).

Antidepressant medication may be used as initial treatment modality for patients with mild, moderate, or severe major depressive disorder. Clinical features that may suggest that medication are the preferred treatment modality includes history of prior positive response to antidepressant medication, severity of symptoms, significant sleep and appetite disturbance, agitation, or anticipation of the need for maintenance therapy. Patients with severe depression with psychotic features will require use of combination of antidepressant and antipsychotic medication and/or ECT.

The initial selection of an antidepressant medication is largely be based on the anticipated side effects, the safety or tolerability of these side effects for individual patients, patient preference and comorbid physical illnesses.

Dose and duration of antidepressants: Once an antidepressant medication has been selected, it can be started initially at lower doses and careful monitoring to be done to assess the response to pharmacotherapy as well as the emergence of side effects, clinical conditions, and safety. Factors to consider when determining the frequency of monitoring include severity of illness, patient's cooperation and presence with treatment, and availability of social support andpresence of comorbid general medical problems. Visits may be frequent enough to monitor and address suicidality and to promote treatment adherence. Improvement with pharmacotherapy can be observed after 4-6 weeks of treatment. If at least a moderate improvement is not observed in this time period, reappraisal and adjustment of the pharmacotherapy maybe considered.

In the initial phase, depending on the symptom severity and type of symptoms, such as presence of insomnia or anxiety, benzodiazepines or other hypnotics may be used for short duration.

Failure to response: If at least some improvement (>25%) is not observed following 4 week of pharmacotherapy, a reappraisal of the treatment regimen be conducted and a change in antidepressant may be considered. When patient shows 25-50% improvement during the initial 4 weeks of antidepressant trial, the dose must be optimized to the maximum tolerable dose. If there is less than 50% improvement with 6-8 weeks of maximum tolerable dose and the medication compliance is good, a change in antidepressant may be considered.

If after 4-8 weeks of treatment, if a moderate improvement is not observed, then a thorough review and reappraisal of the diagnosis, complicating conditions and issues, and treatment plan may be conducted. Reappraisal of the treatment regimen may also include evaluation of patient adherence and pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic factors. Following this review, the treatment plan can be revised by implementing one of several therapeutic options, including maximizing the initial medication treatment, switching to another antidepressant medication, augmenting antidepressant medications with other agents/psychotherapy/ECT. Maximizing the initial treatment regimen is perhaps the most conservative strategy. While using the higher therapeutic doses, patients are to be closely monitored for an increase in the severity of side effects or emergence of newer side effects.

Switching to a different antidepressant medication is a common strategy for treatment-refractory patients, especially those who have not shown at least partial response to the initial medication regimen. There is no consensus about switching and patients can be switched to an antidepressant medication from the same pharmacologic class (e.g., from an SSRI to another SSRI) or to one from a different pharmacologic class (e.g., from an SSRI to a tricyclic antidepressant). Some expert suggests that while switching, a drug with a different or broader mechanism of action may be chosen.

Augmentation of antidepressant medications may be helpful, particularly for patients who have had a partial response to initial antidepressant monotherapy. Options include adding a second antidepressant medication from a different pharmacologic class, or adding another adjunctive medication such as lithium, psychostimulants, modafinil, thyroid hormone, an anticonvulsant etc. Adding, changing, or increasing the intensity of psychotherapy may be considered for patients who do not respond to medication treatment. Following any change in treatment, close monitoring need to be done. If at least a moderate level of improvement in depressive symptoms is not seen after an additional 4–8 weeks of treatment, another thorough review need to be done. This reappraisal may include verifying the patient's diagnosis and adherence; identifying and addressing clinical factors that may be preventing improvement, such as the presence of comorbid general medical conditions or psychiatric conditions (e.g., alcohol or substance abuse); and identifying and addressing psychosocial issues that may be impeding recovery. If no new information is uncovered to explain the patient's lack of adequate response, depending on the severity of depression, ECT maybe considered.

Choice of a specific psychotherapy: Out of the various psychotherapeutic interventions used for management of depression, there is robust level of evidence for use of CBT. The major determinants of type of psychotherapy are patient preference and the availability of clinicians with appropriate training and expertise in specific psychotherapeutic approaches. Other clinical factors which will influence the type of psychotherapy include the severity of the depression. Psychotherapy is usually recommended for patients with depression who are experiencing stressful life events, interpersonal conflicts, family conflicts, poor social support and comorbid personality issues.

The optimal frequency of psychotherapy may be based on specific type and goals of the psychotherapy, the frequency necessary to create and maintain a therapeutic relationship, the frequency of visits required to ensure treatment adherence, and the frequency necessary to monitor and address suicidality. Other factors which would also determine the frequency of psychotherapy visits include the severity of illness, the patient's cooperation with treatment, the availability of social supports, cost, geographic accessibility, and presence of comorbid general medical problems.

Besides the use of specific psychotherapy, all patients and their caregivers may receive psychoeducation about the illness.

Role of Yoga and Meditation in management of depression: Studies related to role of traditional therapies like meditation, Yoga and other techniques have been mostly published in documents of various organizations propagating that particular technique. Well-designed scientific studies to authenticate these claims need to be conducted; however, efficacy of these techniques as supportive/adjuctive therapy is widely accepted.

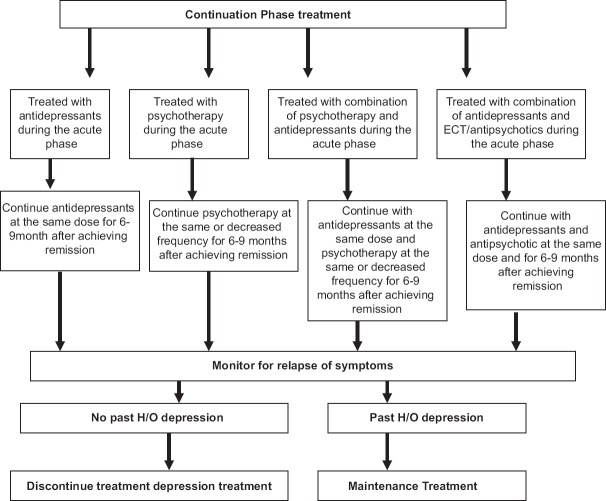

TREATMENT IN CONTINUATION PHASE

The goal of continuation phase is to maintain the gains achieved in the acute phase of treatment and prevent relapse of symptoms. The treatment algorithm to be followed is shown in figure-4. Patients who have been treated with antidepressants in the acute phase need to be maintained on same dose of these agents for 16-24 weeks to prevent relapse (total period of 6-9 month from initiation of treatment). There are evidences to support the use of specific psychotherapy in continuation phase to prevent relapse. The use of other somatic modalities (e.g. ECT) may be useful in patients where pharmacology and/or psychotherapy have failed to maintain stability in continuation phase. The frequency of visit during the continuation phase may be determined by patient's clinical condition as well as the specific treatment being provided. If maintenance phase treatment is not indicated for patients who remain stable following the continuation phase, patients may be considered for discontinuation of treatment. If treatment is discontinued, careful monitoring be done for relapse, and treatment to be promptly reinstituted if relapse occurs.

Figure 4.

Treatment algorithm for continuation phase treatment of depression

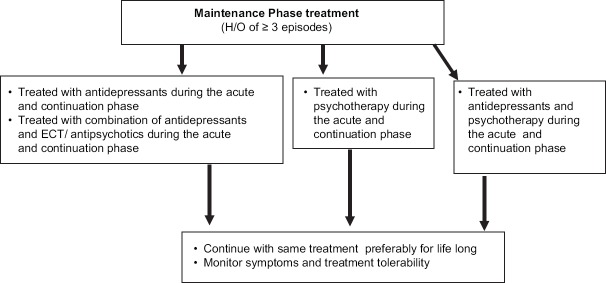

TREATMENT IN MAINTENENCE PHASE

The goal of maintenance phase treatment is to prevent recurrence of depressive episodes. On an average, 50-85% of patients with a single episode of major depression have at least one more episodes. Therefore, maintenance phase treatment may be considered to prevent recurrence. The duration of treatment may be decided keeping in view the previous treatment history and number of depressive episodes the person has had in the past. Mostly the treatment that was effective for acute and continuation phase need to be used in the maintenance phase (Figure-5). Same doses of antidepressants, to which the patient had responded in previous phase is considered. The frequency of visit for CBT and IPTcan be reduced during the maintenance phase (once a month). There is no consensus regarding the duration and when to give and when not to give maintenance treatment. There is agreement to large extent that patients who have history of three or more relapses or recurrences need to be given long-term treatment.

Figure 5.

Treatment algorithm for maintenance phase of depression

DISCONTINUATION OF TREATMENT

The decision to discontinue maintenance treatment may be based on the same factors considered in the decision to initiate maintenance treatment, including the probability of recurrence, the frequency and severity of past episodes, the persistence of depressive symptoms after recovery, the presence of comorbid disorders, and patient preferences. When the decision is made to discontinue or terminate psychotherapy in the maintenance phase, the manner in which this is done may be individualized to the patient's needs. When the decision is made to discontinue maintenance pharmacotherapy, it is best to taper the medication over the course of at least several weeks to few months. Such tapering may allow for the detection of emerging symptoms or recurrences when patients are still partially treated and therefore can be easily returned to full therapeutic intensity. In addition, such tapering can help minimize the risks of antidepressant medication discontinuation syndromes. Discontinuation syndromes have been found to be more frequent after discontinuation of medications with shorter half-lives, and patients maintained on short-acting agents may be given even longer, more gradual tapering. Paroxetine, venlafaxine, TCAs, and MAOIs tend to have higher rates of discontinuation symptoms while bupropion-SR, citalopram, fluoxetine, mirtazapine, and sertraline have lower rates. The symptoms of antidepressants discontinuation include flu-like symptoms, insomnia, nausea, imbalance, sensory disturbances (e.g., electrical sensations) and hyperarousal (agitation). If the discontinuation syndrome is mild, reassurance may be sufficient. If mild to moderate, short-term symptomatic treatment (analgesics, antiemetics, or anxiolytics) may be beneficial. If it is severe, antidepressant are to be reinstated and tapered off more slowly.

After the discontinuation of active treatment, patients should be reminded of the potential for a depressive relapse. Patient may be again informed about the early signs of depression, and a plan for seeking treatment in the event of recurrence of symptoms may be formulated. Patients may be monitored for next few months to identify relapse. If a patient suffers a relapse upon discontinuation of medication, treatments need to be promptly reinitiated. In general, the previous treatment regimen to which the patient responded in the acute and continuation phase are to be considered.

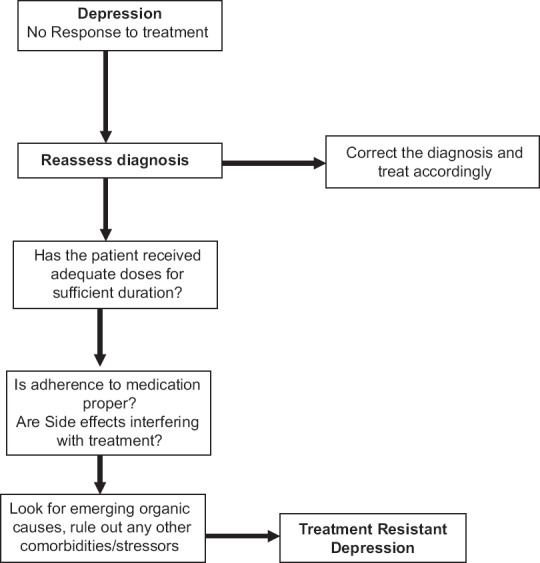

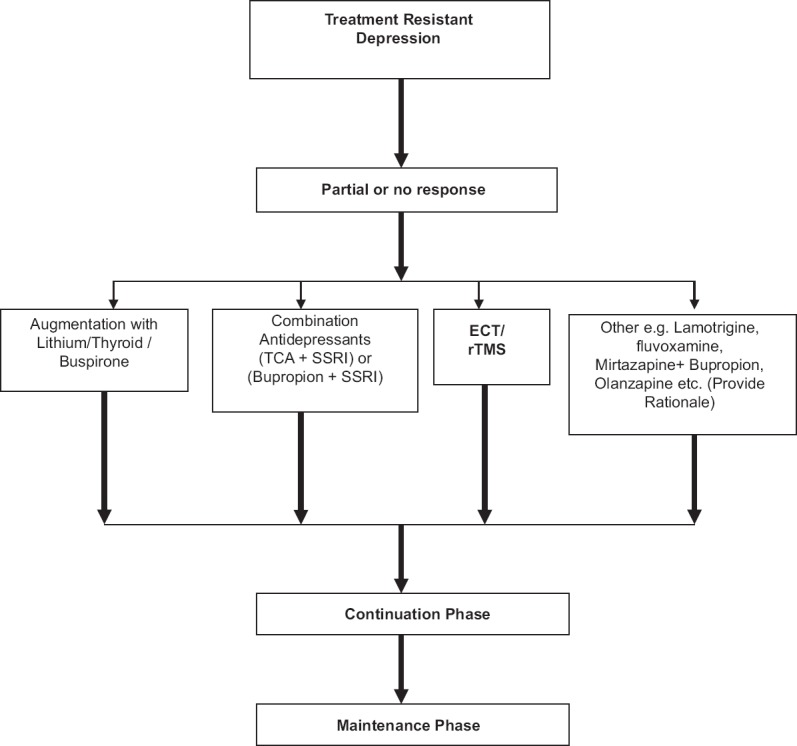

MANAGEMENT OF TREATMENT RESISTANCE DEPRESSION

Initial treatment with antidepressant medication fails to achieve a satisfactory response in approximately 20%-30% of patients with depressive disorder. In some cases the apparent lack of treatment response is actually a result of faulty diagnosis, inadequate treatment, or failure to appreciate and remedy coexisting general medical and psychiatric disorders or other complicating psychosocial factors. Adequate treatment for at least 4-6 weeks is necessary before concluding that a patient is not responsive to a particular medication. First step in care of a patient who has not responded to medication is carrying out a thorough review and reappraisal of the psychosocial and biological information base, aimed at revarifying the diagnosis and identifying any neglected and possibly contributing factors, including the general medical problems, alcohol or substance abuse or dependence, other psychiatric disorders, and general psychosocial issues impeding recovery. Algorithm for arriving at the diagnosis of treatment resistant depression is given in figure-6.

Figure 6.

Algorithm for arriving at the diagnosis of Treatment Resistant Depression

Some clinicians require two successive trials of medications of different categories for adequate duration before considering treatment resistant depression (TRD). Management of TRD involves addition of an adjunctive agent, combining two antidepressants, addition of ECT or other somatic treatments like rTMS. Algorithm for management of TRD is given in figure-7.

Figure 7.

Algorithm for management of Treatment Resistant Depression

Addition of an adjunct to an antidepressant: Lithium is the drug primarily used as an adjunct; other agents in use are thyroid hormone and stimulants. Opinion differs as to the relative benefits of lithium and thyroid supplementation. It is reported that lithium is useful in over 50% of antidepressant nonresponders and is usually well tolerated. The interval before full response to adjunctive lithium is said to be in the range of several daysto 3 weeks. If effective and well tolerated, lithium may be continued for the duration of treatment of the acute episode. Thyroid hormone supplementation, even in euthyroid patients, may also increase the effectiveness of antidepressant treatment. The dose proposed for this purpose is 25 µg/day of triidothyronine increased to 50 µg/day in a week.

Simultaneous use of multiple antidepressants: Depression is a chronic disabling condition in case patient does not respond to single drug regimen; clinicians may use combination/ polytherapy with close monitoring of side effects and drug interaction profile. Combinations of antidepressant carry a risk of adverse interaction and sometimes require dose adjustments. Use of a SSRI in combination with TCA has been reported to induce a particularly rapid antidepressant response. However, fluoxetine added to TCAs causes an increased blood level and delayed elimination of the TCA, predisposing the patient to TCA drug toxicity unless the dose of the TCA is reduced. Another strategy involves combined use of a tricyclic antidepressant and a MAO inhibitor, a combination that is sometimes effective in alleviating severe medication-resistant depression, but the risk of serotonin syndrome necessitates careful monitoring.

Electroconvulsive therapy: Response to ECT is generally good and the response rates are like any form of antidepressant treatment and it may be considered in virtually all cases of moderate or severe major depression who do not respond to pharmacologic intervention. Approximately 50% of medication resistant patients exhibit a satisfactory response to ECT. Lithium may be discontinued before initiation of ECT, as it has been reported to prolong postictal delirium and delay recovery from neuromuscular blockade.

Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS)

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS; a type of TMS that occurs in a rhythmic and repetitive form) has been put forward as a new technique to treat this debilitating illness. Current evidence suggests that rTMS applied to the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) is a promising treatment strategy for depression, but not all patients show a positive outcome. Current clinical outcome studies report rather modest superiority compared with placebo (sham). To date, it remains unclear which TMS parameters, such as stimulation duration and intensity, can produce the most benefits. Moreover, there is no consensus of the exact brain localization for individual coil placement.

MANAGEMENT OF SPECIAL CONDITIONS

Clinicians often encounter certain clinical situations which either require special attention or can influence treatment decisions. Management of these situations is summarized in table-11.

Table 11.

Management of depression Special situations

REFERENCES

- 1.American Psychiatry Association. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder, Third Edition. 2010:152. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avasthi A, Grover S, Agarwal M. Research on antidepressants in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52(Suppl):S341–354. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.69263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avasthi A, Grover S, Bharadwaj R. Shiv Gautam, Ajit Avasthi, editors. Clinical Practice guidelines for treatment of depression in old age. Published by Indian Psychiatric Society. 2007;III:51–150. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellis P. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists Clinical Practice Guidelines Team for Depression. Australian and New Zealand clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of depression. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2004 Jun;38(6):389–407. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2004.01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gautam S, Batra L. Clinical Practice guidelines for management of depression. In: Shiv Gautam, Ajit Avasthi, editors. Published by Indian Psychiatric Society. I. 2005. pp. 83–119. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grover S, Dutt A, Avasthi A. Research on Depression in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52(Suppl):S178–S188. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.69231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kennedy SH, Lam RW, McIntyre RS, Tourjman SV, Bhat V, Blier P, Hasnain M, Jollant F, Levitt AJ, MacQueen GM, McInerney SJ, McIntosh D, Milev RV, Müller DJ, Parikh SV, Pearson NL, Ravindran AV, Uher R CANMAT Depression Work Group. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Adults with Major Depressive Disorder: Section 3. Pharmacological Treatments. Can J Psychiatry. 2016 Aug 2; doi: 10.1177/0706743716659417. pii: 0706743716659417. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 27486148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kessler RC, Bromet EJ. The epidemiology of depression across cultures. Annu Rev Public Health. 2013;34:119–38. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lam RW, Kennedy SH, Grigoriadis S, McIntyre RS, Milev R, Ramasubbu R, Parikh SV, Patten SB, Ravindran AV. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT). Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder in adults. III. Pharmacotherapy. J Affect Disord. 2009 Oct;117(Suppl 1):S26–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Depression in adults: Recognition and Management. Clinical guideline (cg 90) 2009:5–64. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parikh SV, Segal ZV, Grigoriadis S, Ravindran AV, Kennedy SH, Lam RW, Patten SB Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder in adults. II. Psychotherapy alone or in combination with antidepressant medication. J Affect Disord. 2009 Oct;117(Suppl 1):S15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Royal Australian And New Zealand College Of Psychiatrists Clinical Practice Guidelines Team For Depression. Australian and New Zealand clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of depression. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;38:6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarkar S, Grover S. A systematic review and meta-analysis of trials of antidepressants in India for treatment of depression. Indian J Psychiatry. 2014;56:29–38. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.124711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh T, Rajput M. Misdiagnosis of Bipolar Disorder. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2006;3:57–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]