Abstract

Background

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are the treatment of choice for most patients with atrial fibrillation and/or noncancer-associated venous thromboembolic disease. Although routine monitoring of these agents is not required, assessment of anticoagulant effect may be desirable in special situations. The objective of this review was to summarize systematically evidence regarding laboratory assessment of the anticoagulant effects of dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban.

Methods

PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science were searched for studies reporting relationships between drug levels and coagulation assay results.

Results

We identified 109 eligible studies: 35 for dabigatran, 50 for rivaroxaban, 11 for apixaban, and 13 for edoxaban. The performance of standard anticoagulation tests varied across DOACs and reagents; most assays, showed insufficient correlation to provide a reliable assessment of DOAC effects. Dilute thrombin time (TT) assays demonstrated linear correlation (r2 = 0.67-0.99) across a range of expected concentrations of dabigatran, as did ecarin-based assays. Calibrated anti-Xa assays demonstrated linear correlation (r2 = 0.78-1.00) across a wide range of concentrations for rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban.

Conclusions

An ideal test, offering both accuracy and precision for measurement of any DOAC is not widely available. We recommend a dilute TT or ecarin-based assay for assessment of the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran and anti-Xa assays with drug-specific calibrators for direct Xa inhibitors. In the absence of these tests, TT or APTT is recommended over PT/INR for assessment of dabigatran, and PT/INR is recommended over APTT for detection of factor Xa inhibitors. Time since last dose, the presence or absence of drug interactions, and renal and hepatic function should impact clinical estimates of anticoagulant effect in a patient for whom laboratory test results are not available.

Key Words: antithrombotic therapy, deep venous thrombosis, direct oral anticoagulants, laboratory, pulmonary embolism

Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; CHEST, American College of Chest Physicians; DOAC, direct oral anticoagulant; DRVVT, dilute Russell viper venom time; ECT, ecarin clotting time; ETP, endogenous thrombin potential; ISTH, International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis; LC-MS/MS, liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry; PiCT, prothrombinase-induced clotting time; PT/INR, prothrombin time/international normalized ratio; TEG, thromboelastography; TT, thrombin time

The development of an oral thrombin inhibitor (dabigatran) and oral factor Xa inhibitors (rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban) has changed the management of anticoagulation in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF) and VTE. As of January 2016, the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) and other organizations recommended these drugs over vitamin K antagonists as the agents of choice for management of noncancer-associated VTE.1, 2 Guidelines from the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and Heart Rhythm Society published in 2014 include vitamin K antagonists and direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) for stroke prevention in AF but do not recommend one over the other.3 Although these drugs, collectively referred to as DOACs, are administered in fixed doses and do not require routine laboratory monitoring for dose adjustment,4, 5, 6, 7 there are a number of circumstances in which assessment of a DOAC’s effect may be desirable. Some examples of when an assay with rapid turnaround time, if available, could directly impact patient care include emergent settings, such as life-threatening bleeding; requirement for epidural procedures; emergency surgery; and acute stroke in a patient who might otherwise be a candidate for thrombolysis. In other settings, such as overdose, GI malabsorption, extremes of body weight, drug interactions, acute renal injury, and treatment failure, a less rapid but precise assay would be desirable.8

The anticoagulant effect of a DOAC is generally assumed to be directly proportional to its plasma concentration as measured by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). LC-MS/MS is the most accurate way to assess drug concentration, but this technology is not widely available. The range of concentrations over which the DOACs have adequate or therapeutic anticoagulant effect is not known, although a number of studies have published results of pharmacokinetic analysis, including ranges of peak and trough levels in patients receiving therapy (Table 1). We refer to levels within this range as the ‘on therapy’ range throughout this paper. Levels below the reported 5th percentile trough are referred to as below ‘on therapy’ range, and levels above the reported 95th percentile peak are referred to as above ‘on therapy’ range. The majority of patients are expected to have levels within the ‘on therapy’ range at any time during treatment. The most accurate assays are those that correlate best with LC-MS/MS results.

Table 1.

Expected Steady-State Peak and Trough Concentrations of Dabigatran, Rivaroxaban, Apixaban, and Edoxaban in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation

We previously published a systematic review evaluating the degree to which coagulation assays can help estimate the concentration (and therefore the effect) of dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban activity.9 Additionally, the American College of Chest Physicians published guidelines for quantification and screening in 2012,10 as did the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH).11 Since then, a number of studies have been published, and a third anti-Xa agent, edoxaban, has been approved.12 Here, we update our previous systematic review with a broadened search strategy, the addition of data on edoxaban, and the inclusion of studies published between December 2, 2013, and July 1, 2015.

Materials and Methods

Literature Search

We performed a systematic review of the literature to examine use of coagulation assays for assessment of the anticoagulant activity of DOACs. A search of PubMed, Web of Science, and Embase from inception through July 1, 2015, was undertaken for dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban using the key words “name of drug” AND (monitoring OR measurement OR laboratory OR prothrombin time OR partial thromboplastin time OR activated partial thromboplastin time OR PT OR APTT). For anti-Xa agents (anti-Xa OR anti-factor Xa) were also included. For dabigatran (thrombin time OR TT or thrombin clot time OR TCT or dilute thrombin time OR dilute TT OR ecarin) were also included.

Study Selection

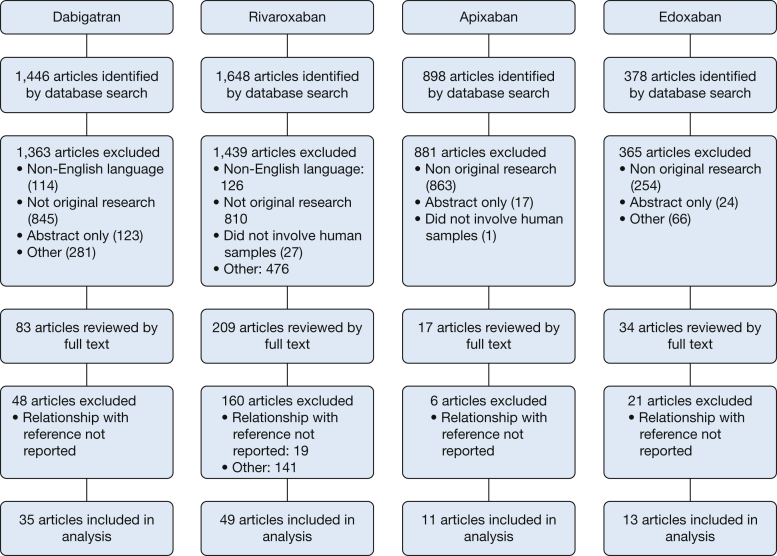

Articles were examined by title and abstract. A complete review of papers appearing to meet inclusion criteria was undertaken. We included studies that compared the results of one or more clinical coagulation assays with drug concentrations established either by measurement with direct LC-MS/MS or by LC-MS/MS-validated calibration standards. Studies performed on animals, studies published as abstracts only, and non-English-language articles were excluded. Reasons for exclusion are included in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

This Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram illustrates dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and rivaroxaban literature searches.

Data Extraction

Key characteristics, including author, year of publication, setting, reference method for measurement of drug levels, range of drug concentration studied, test material (ex vivo vs spiked plasma, patient vs volunteer), number of samples, coagulation assays and reagents, and descriptors of the relationship between drug level and coagulation assay, were extracted and recorded in evidence tables.

Results

Dabigatran

Dabigatran etexilate is taken orally as an inactive nonpeptide prodrug and is rapidly converted by nonspecific esterases to a potent, direct inhibitor of free- and fibrin-bound thrombin. Absorption is rapid, but bioavailability is only 6.5%. The half-life is 12 to 14 hours, and elimination is 80% renal.13 The expected steady-state concentrations of dabigatran as measured by LC-MS/MS are shown in Table 1.

Study Selection

From 1,446 papers, we excluded 114 that were non-English-language publications, 845 that were not original research publications, 123 that were published as abstracts only, 166 that did not involve human subjects, 66 that did not involve dabigatran, and 97 that did not report a relationship between the clinical coagulation assays and concentrations established by LC-MS/MS (Fig 1). The remaining 35 articles14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48 were eligible for inclusion. Eligible studies were conducted in 12 countries across a range of dabigatran concentrations from 0 to 1,886 ng/mL. Eight studies used ex vivo plasma from patients treated with dabigatran,14, 16, 17, 18, 29, 35, 36, 37, 42 and the remainder involved ex vivo volunteer plasma or plasma spiked in vitro with dabigatran as the test material (e-Table 1).

Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time

Twenty-two eligible studies14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 21, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 32, 33, 35, 36, 39, 40, 45, 48 reported simultaneous measurement of activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) and dabigatran levels. Although the APTT was often prolonged, degree of prolongation correlated poorly with concentration, especially at higher APTT values. Furthermore, responsiveness varied across reagents, and several studies14, 16, 36 reported that selected APTT assays can yield normal results in the presence of trough-like dabigatran concentrations.

Prothrombin Time/International Normalized Ratio

Eighteen eligible studies14, 17, 18, 23, 24, 26, 27, 29, 30, 33, 36, 38, 41, 46, 47, 48 reported simultaneous measurement of prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (PT/INR) and dabigatran levels. The sensitivity of INR was low for the presence of dabigatran, particularly within and below the therapeutic range.30, 33, 36, 40 PT and INR often exceeded the upper limits of the assay at dabigatran concentrations above the ‘on therapy’ range.41

Thrombin Time

Eleven eligible studies15, 16, 17, 18, 21, 23, 28, 29, 38, 42, 48 reported simultaneous measurements of thrombin time (TT) and dabigatran levels. TT, in general, was overly sensitive, with results often exceeding the upper limit of the assay at or even below the ‘on therapy’ range.15, 17, 18, 21 A normal TT effectively excluded the presence of dabigatran across all studies.

Dilute TT

Seventeen eligible studies14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 21, 22, 23, 25, 29, 31, 34, 35, 36, 37, 42, 44 reported simultaneous measurement of dilute TT and dabigatran levels. The majority of studies used the Hemoclot thrombin inhibitor assay (Hyphen BioMed). Dilute TT results showed a strong, linear correlation with dabigatran concentrations in the ‘on therapy’ range. The correlation, though still present, was weaker at low (< 50 ng/mL) and high (> 500 ng/mL) dabigatran concentrations.14, 25, 31, 34

Ecarin-based Assays

Fourteen studies14, 19, 21, 22, 23, 25, 27, 28, 29, 32, 35, 36, 39, 42 reported an association between ecarin-based assays, including ecarin clotting time (ECT) and/or ecarin clotting assay, and dabigatran levels. Ecarin is a metalloproteinase that cleaves prothrombin to an active intermediate called meizothrombin, which is inhibited by dabigatran much as thrombin is, a property that can be exploited for measurement of dabigatran in ecarin-based assays. Assays demonstrated high sensitivity for the presence of and strong correlation with the concentration of dabigatran below, within, and above ‘on therapy’ ranges, although this decreased somewhat at extremes (< 40 ng/mL or > 940 ng/mL).22, 29

Other Assays

Relationships between a number of different assays and dabigatran levels were reported in one or two articles each, including dilute prothrombin time, prothrombinase-induced clotting time (PiCT) and activated clotting time, rotational thromboelastometry, endogenous thrombin potential (ETP), the dilute Russell viper venom time (DRVVT), and thromboelastography (TEG).20, 23, 29, 30, 43, 45 None of these tests demonstrated adequate sensitivity to support routine use either for excluding the presence of dabigatran or for determining dabigatran concentration.

Rivaroxaban

Rivaroxaban is a competitive inhibitor of free and clot-based factor Xa.49 Oral bioavailability is 80% to 100% after a 10-mg dose and 66% after a 20-mg dose.50 Peak plasma levels are reached approximately 2 to 4 hours after administration.51, 52 Mathematical modeling predicts median peak and trough concentrations of 274 and 30 ng/mL, respectively, in patients receiving 20 mg daily for AF (Table 1).53 Rivaroxaban is excreted partially by the kidneys (36%) and has a half-life of 6 to 13 hours, depending on the dose and the age of the recipient.10, 50, 51, 52, 54

Study Selection

Of 1,648 articles identified in our search, 1,439 studies were excluded after title and abstract screening (Fig 1). Of the 209 full-text articles reviewed, 160 were subsequently excluded for the following reasons: not original research (n = 128), no relationship reported between drug levels and coagulation test (n = 23), not rivaroxaban (n = 4), duplicate (n = 4), and non-English language (n = 1). Therefore, 49 studies20, 24, 40, 42, 43, 46, 47, 48, 51, 52, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93 were included in the final review. Eligible studies were conducted in 12 countries across a range of rivaroxaban concentrations from 0 to 20,000 ng/mL. Fifteen studies used ex vivo plasma from patients treated with rivaroxaban, and the remainder involved ex vivo volunteer plasma or plasma spiked in vitro with rivaroxaban as the test material (e-Table 2).

Prothrombin Time

We found 35 studies24, 40, 45, 46, 47, 48, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 66, 67, 68, 70, 73, 75, 76, 77, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 90, 91, 92 evaluating the effect of rivaroxaban on PT (e-Table 2). Overall, rivaroxaban prolonged the PT in a concentration-dependent manner, but the correlation was generally weak24, 45, 46, 61, 62, 63, 66, 80, 86, 89 and became weaker with increasing concentrations (> 50-100 ng/mL).63 Significant reagent-dependent differences in assay sensitivity were noted in multiple studies.40, 48, 60, 61, 62, 63, 66, 76, 90

APTT

Seventeen studies24, 40, 48, 58, 59, 61, 62, 66, 68, 73, 76, 79, 80, 85, 86, 89, 91 assessed the effect of rivaroxaban on APTT. A poor to moderate concentration-dependent prolongation of the APTT was noted.48, 61, 62, 68, 73, 76, 80, 81, 85, 89 APTT assay sensitivity was reagent dependent.40, 48, 62, 76, 80, 91 Variability within assays40, 80 and between laboratories (coefficient of variation, 14.3%-15.5%)45, 48, 56, 71, 89 was also reported.

Anti-Factor Xa Activity

Thirty studies40, 48, 51, 52, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 76, 80, 82, 83, 84, 86, 89, 91 assessed the effect of rivaroxaban on anti-Xa activity (e-Table 2). Rivaroxaban-calibrated chromogenic anti-Xa activity assays showed linear, concentration-dependent correlations (r2 = 0.95-1.00) over a wide range of rivaroxaban concentrations (0-755 ng/mL). The linear association between rivaroxaban and anti-Xa activity was marginally lower when assays were calibrated with unfractionated heparin (r2 = 0.90-0.99) or low-molecular-weight heparin (r2 = 0.92-0.98). Some assays showed variability at low and/or high concentrations48, 77, 88 and reduced accuracy at upper and lower limits of quantitation.63, 71

Thrombin Generation

The effect of rivaroxaban on thrombin generation was evaluated in 11 studies.46, 56, 58, 62, 69, 77, 80, 85, 86, 89, 91 Rivaroxaban produced dose-dependent effects on all thrombin generation parameters including lag time, peak thrombin generation, time to peak thrombin generation, ETP, and velocity rate index. However, sensitivity was variable. ETP (area under the curve) seemed to have lower responsiveness to rivaroxaban concentration than did the lag time, peak thrombin generation, time to peak thrombin generation, or velocity rate index.80, 85, 89

Other Assays

Relationships between a number of assays and rivaroxaban levels were reported in one to six articles each, including DRVVT,45, 56, 71, 89 dilute prothrombin time,56, 62, 89 PiCT,62, 70, 73, 78, 89 thromboelastometry,43, 55, 79 TEG,20, 86, 89 activated clotting time,43, 62, 66 and ECT.56, 62 None of these tests demonstrated adequate sensitivity to support routine use either for excluding the presence of rivaroxaban or for determining rivaroxaban concentration.

Apixaban

Apixaban, a direct inhibitor of coagulation factor Xa, is a small molecule with 50% oral bioavailability. In healthy volunteers, apixaban achieves its peak plasma concentration approximately 3 hours after ingestion. Apixaban pharmacokinetics is not affected by food intake, and apixaban is highly protein bound in the plasma.94 Because apixaban metabolism occurs via several different routes, this drug is less dependent on renal clearance than are other approved DOACs. In people with normal renal function, the half-life of apixaban is approximately 12 hours.95 The expected steady-state concentrations of apixaban as measured by LC-MS/MS have been published94 and are shown in Table 1.

Study Selection

Our literature search yielded 898 titles. Of these, we excluded 863 that did not report original research, 17 published as abstract only, six that did not report levels measured by both LC-MS/MS and a coagulation assay, and one that did not involve human samples. The remaining 11 articles55, 60, 61, 67, 77, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101 met eligibility criteria (Fig 1). Eligible studies collectively evaluated apixaban across a range of concentrations from 0 to 2,500 ng/mL (e-Table 3).

PT/INR

Five studies60, 96, 98, 99, 100 reported the relationship between PT and apixaban levels (e-Table 3). Two studies reported a linear or curvilinear relationship,60, 96 and one found none.99 Across in vitro and ex vivo samples and for a variety of reagents, PT was inadequately sensitive to apixaban, not only below but also substantially > 50 ng/mL.

APTT

Four studies61, 98, 99, 100 compared apixaban concentrations with APTT. A weak correlation between APTT and apixaban concentration was reported in one study.36 All studies showed that the sensitivity of APTT is unacceptably low. All assays yielded normal times at apixaban concentrations of 100 ng/mL.

Anti-Xa Activity

Four studies60, 97, 98, 99 compared anti-Xa activity measurements with the plasma concentration of apixaban (e-Table 3). The majority of studies demonstrated that anti-Xa activity varied linearly with apixaban concentration, but at least one study suggested that the correlation between anti-Xa activity and apixaban concentration may be less strong at low (15-50 ng/mL) concentrations.99

Thrombin Generation

Three studies77, 100, 101 compared thrombin generation assay results with the plasma concentration of apixaban (e-Table 3). Apixaban affected all parameters in a dose-dependent fashion, but sensitivity varied. There is insufficient evidence to recommend the use of thrombin generation for the assessment of apixaban effect in clinical practice.

Other Assays

Coagulation assays based on elastography or elastometry (eg, TEG and rotational thromboelastometry) showed some promise in their ability to detect the presence of apixaban.20, 43, 55, 100 Additional evidence will be needed before one or more of these assays can be recommended as the method of choice for detecting and quantifying the anticoagulant effect of any DOAC.

Edoxaban

Edoxaban is a direct inhibitor of factor Xa. Oral bioavailability is 62% and is not affected by food. Peak plasma concentration is achieved 1 to 2 hours after ingestion, and terminal half-life is 10 to 14 hours. Renal excretion accounts for approximately one-half of total clearance of edoxaban, with the remainder accounted for by metabolism and biliary/intestinal excretion. The predominant metabolite of edoxaban, M-4, has anticoagulant activity and reaches less than 10% of the exposure of the parent compound in healthy subjects. Steady-state peak and trough concentrations in patients taking edoxaban 60 mg daily have been estimated based on pharmacokinetic modeling and are shown in Table 1.102

Study Selection

Our literature search identified 378 articles. Thirteen met eligibility criteria and were included in the analysis.103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115 The remaining 365 references were excluded: 254 did not report an original research study, 24 were published in abstract form only, 45 did not involve human samples, 21 did not involve edoxaban, and 21 did not report a relationship between plasma edoxaban levels and one or more coagulation assays (Fig 1). Eligible studies collectively evaluated samples across a range of edoxaban concentrations from 0 to > 1,200 ng/mL (e-Table 4).

PT/INR

Nine studies103, 104, 108, 109, 110, 111, 113, 114, 115 reported a relationship between the PT/INR and plasma edoxaban levels. Edoxaban prolonged the PT in a concentration-dependent, linear fashion, but assays were insufficiently sensitive at low therapeutic levels. Different PT reagents varied widely in their sensitivity to edoxaban.109, 113

APTT

Eight studies105, 108, 109, 110, 111, 113, 114, 115 reported a relationship between edoxaban levels and APTT. Edoxaban prolonged APTT in a dose-dependent manner with fair correlation in both in vitro and ex vivo studies. APTT was less sensitive to edoxaban than was PT. In some studies, edoxaban concentrations of 300 to > 600 ng/mL were needed to double the APTT from baseline, depending on the reagent.109, 113

Anti-Xa Activity

A relationship between anti-Xa activity and edoxaban levels was reported in nine studies.104, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 113, 114, 115 Anti-Xa activity increased in a dose-dependent linear fashion, with an r2 value exceeding 0.90 in five of six studies.107, 108, 111, 113, 114 Anti-Xa activity was measurable with low doses of edoxaban, but accuracy and precision were reduced at edoxaban levels > 200 to 300 ng/mL.111, 114

Thrombin Generation Assay

Six studies105, 106, 107, 109, 113, 115 reported a relationship between edoxaban levels and the thrombin generation assay using the Calibrated Automated Thrombogram system (Thrombinoscope BV). Edoxaban decreased peak thrombin generation, mean rate, and ETP and increased lag time and time to peak in a concentration-dependent manner. The thrombin generation assay was more sensitive to edoxaban than were PT and APTT. Peak thrombin generation and mean rate were the most sensitive parameters.

Other Assays

One study each reported a relationship between edoxaban concentration and DRVVT,113 PiCT,113 and TT.104 None of these tests demonstrated adequate sensitivity or had adequate data to support routine use either for excluding the presence of edoxaban or for determining edoxaban concentration.

Discussion

Although there are no established therapeutic ranges for any of these drugs or evidence to support routine monitoring with or without titration of dose, there are a variety of circumstances in which assessing anticoagulant effect may be useful. A number of professional societies, including the ISTH and CHEST, have published recommendations for urgent or routine assessment of the anticoagulant effects of direct thrombin inhibitors and anti-Xa agents. In this systematic review, we have examined and presented evidence regarding the usefulness of a variety of coagulation assays to assess the anticoagulant activity of dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban.

Summary of Available Data

Dabigatran

The dilute TT and ecarin-based clotting assays provide the best correlation with plasma concentration. A normal TT excludes the presence of dabigatran. APTT is often, but not always, prolonged by the presence of trough-like or greater concentrations of dabigatran (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of the Usefulness of Common Coagulation Assays for Assessment of Anticoagulant Effect of DOACs

| Coagulation Assay | Relationship to Expected ‘On Therapy’ Range | Dabigatran | Rivaroxaban | Apixaban | Edoxaban |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APTT | |||||

| Below | Normal or prolongeda | Normal limits | Normal limits | Normal limits | |

| Within | Prolonged | Normal or prolongedb | Normal or prolongedb | Normal limits | |

| Above | Prolonged | Normal or prolongedb | Prolonged | Normal or prolongedc | |

| PT/INR | |||||

| Below | Normal limits | Normal limits | Normal limits | Normal limits | |

| Within | Normal or prolongedd | Normal or prolonged | Normal or prolongede | Normal or prolongedf | |

| Above | Normal or prolongedd | Normal or prolonged | Normal or prolongede | Normal or prolongedf | |

| TT | |||||

| Below | Prolonged | Normal | Not indicated | Not indicated | |

| Within | Prolonged/out of range | Normal | Not indicated | Not indicated | |

| Above | Prolonged/out of range | Normal | Not indicated | Not indicated | |

| Dilute TT | |||||

| Below | Normal or prolongedg | Not indicated | Not indicated | Not indicated | |

| Within | Prolongedg | Not indicated | Not indicated | Not indicated | |

| Above | Prolongedg | Not indicated | Not indicated | Not indicated | |

| Anti-Xa | |||||

| Below | Not indicated | Normal or increasedh | Normal or increasedi | Normal or increased | |

| Within | Not indicated | Increased | Increased | Increased | |

| Above | Not indicated | Increased | Increasede | Increasedj |

APTT = activated partial thromboplastin time; DOAC = direct oral anticoagulant; PT/INR = prothrombin time/international normalized ratio; TT = thrombin time.

Results may remain within normal limits at low concentrations (< 70 ng/mL).

Results may remain within normal limits above concentrations of 100 ng/mL.

Concentrations of 300 to 600 ng/mL required to double APTT.

Some reagents have results within normal limits at high concentrations (100-400 ng/mL).

Results remain within normal limits up to a concentration of 50 ng/mL.

Low sensitivity at low therapeutic levels; concentrations from163 to 406 ng/mL required to double PT, depending on reagent.

Highest sensitivity in range of 50 to 500 ng/mL.

Decreased sensitivity at concentrations < 30 ng/mL and reduced accuracy at upper and lower limits of quantification with some reagents.

Decreased sensitivity at concentrations < 15 and > 200 ng/mL.

Decreased accuracy and precision at concentrations > 200 to 300 ng/mL.

Rivaroxaban

Calibrated anti-factor Xa assays provide the best correlation with plasma concentration. Some PT assays correlate well with rivaroxaban concentration, but many do not. A prolonged PT with no other explanation in a patient treated with rivaroxaban indicates drug presence; however, a normal PT does not exclude the possibility of ‘on therapy’ or greater rivaroxaban concentrations (Table 2).

Apixaban

Calibrated anti-factor Xa assays provide the best correlation with plasma concentration. Most PT and APTT assays poorly reflect the anticoagulant effect of apixaban. PT and APTT are not useful to assess whether apixaban is present in clinically important or greater quantities (Table 2).

Edoxaban

Calibrated anti-factor Xa assays provide the best correlation with plasma concentration. For edoxaban, PT is more sensitive than APTT, but there is interreagent variability, and some PT assays are insensitive at trough-like concentrations. A prolonged PT with no other explanation in a patient treated with edoxaban indicates drug presence; however, a normal PT does not exclude the possibility of ‘on therapy’ edoxaban concentrations (Table 2).

Recommendations for Screening and Quantification

Although clinicians should resist the temptation to check levels routinely in the majority of patients because there is no evidence-based approach to interpret or act on these levels, there are circumstances in which assessment of DOAC effect is desirable. A screening assay may be useful in a setting in which a clinician needs to determine quickly the presence or absence of the drug (eg, prior to considering administration of thrombolytics or preoperatively in an urgent or emergent situation). Quantification may be desirable in the setting of uncertain absorption (eg, after bariatric surgery) or abnormal drug clearance (ie, acute kidney injury). We acknowledge that many hospitals may not have rapid access to the assays we recommend later and wish to emphasize that time elapsed since last dose, interpreted in light of possible drug interactions and the patient’s renal and hepatic function, remains a key factor in estimating DOAC effect at any given moment.

Direct Thrombin Inhibitor: Dabigatran

Guidelines published by the ISTH recommend APTT as the test of choice for screening and TT as the test of choice for quantification; CHEST recommends the TT and ECT, respectively.10, 11 Our review of the data suggests that APTT is not sensitive enough to be used routinely for either screening or quantification with a curvilinear dose response; for many assays, APTT remains within normal limits even at therapeutic drug concentrations. TT is a more useful screening tool because normal TT can exclude the presence of a direct thrombin inhibitor but may be prolonged even at clinically nonsignificant levels and is too sensitive for quantification. Ecarin-based assays demonstrate more linear dose-response curves, suggesting usefulness for quantification within the ‘on therapy’ range, although, as with many other assays, reliability decreases at high and low drug concentrations, diminishing their usefulness. Dilute TT assays demonstrate linear dose-response curves with a high degree of correlation.

Unfortunately, availability of the dilute TT is limited. One survey of 592 Australasian coagulation laboratories revealed that only nine offered this test.116 A 2015 survey of 46 specialized coagulation laboratories in North America reported that 22% offered a commercial dilute TT assay for measurement of dabigatran and 6% offered a homemade assay for this purpose; 15% reported offering TT assays, and 9% reported offering ecarin-based assays.117 Availability in smaller laboratories and community hospitals is likely to be significantly less. Additionally, these assays are not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the quantification of dabigatran and must be interpreted in this light.

In these cases, of the assays likely to be available immediately for screening purposes, we favor APTT over PT. However, the clinician should be aware that most APTT assays will be inadequately sensitive to rule out the presence of ‘on therapy’ levels of the drug. In the ideal scenario, the clinical laboratory would have previously performed a dose-response study to define the sensitivity of the local APTT method.

Xa Inhibitors: Rivaroxaban, Apixaban, Edoxaban

ISTH guidelines favor PT as the test of choice for screening and anti-Xa assay as the test of choice for quantification of rivaroxaban and apixaban.11 CHEST favors anti-Xa for quantification of both rivaroxaban and apixaban and recommends against the use of PT to screen for rivaroxaban but makes no recommendation regarding screening for apixaban.10 Neither recommendation specifically addresses edoxaban. Our review of the data supports anti-Xa activity as the test of choice for quantification of all Xa inhibitors, provided that a standard curve established with drug-specific calibrators is used. Correlation between anti-Xa activity and drug concentration is weaker at very low or high concentrations, particularly for apixaban. Thrombin generation may be useful, particularly for rivaroxaban.

As with the assays discussed for dabigatran, we recognize that calibrated anti-Xa assays may not be available in urgent or emergent situations. A survey of coagulation laboratories administered in 2013 revealed that, of 300 centers offering an anti-Xa assay for heparin, only nine had an established standard curve for rivaroxaban.118 During an update of this survey in 2016, an additional 19 laboratories reported use of anti-Xa assays for measurement of rivaroxaban levels.119 A similar survey of 46 specialized coagulation assays in 2015 revealed that 39% offered anti-Xa assays for rivaroxaban and 22% offered this for apixaban.117 Availability for edoxaban was not reported, and, again, availability in local hospitals is likely to be significantly lower. If the clinician needs only to exclude the presence of clinically important drug effect, an anti-Xa assay, even if not calibrated for the relevant DOAC, can be helpful: If no anti-Xa activity is detected, the presence of a clinically important concentration of an oral factor Xa inhibitor is excluded. In cases in which no anti-Xa activity measurement can be performed quickly, we favor PT over APTT for rivaroxaban and edoxaban. However, because interassay variability is also high in this setting, we recommend that, for institutions that will rely on PT to make urgent decisions in patients treated with rivaroxaban or edoxaban, the clinical laboratory should perform a dose-response study with calibration standards to define the sensitivity of the institutional PT assay in advance. Most assays will be inadequately sensitive to exclude clinically significant levels of drug. Both PT and APTT are inadequately sensitive for apixaban, so laboratory evaluation may be of little to no use in the absence of an anti-Xa level.

There are many limitations to the accurate and reliable laboratory assessment of the anticoagulant effect of DOACs. The most accurate assays are unavailable in many clinical settings, and standard coagulation assays, which are available, are often uninterpretable. Expanded availability and US Food and Drug Administration approval of precise assays, such as the dilute TT, ECT, and anti-Xa, is needed. Routine monitoring of renal and hepatic function and medication reconciliation for possible drug interactions in patients treated with DOACs is also essential.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: B. T. S., had full access to all the data in the study and takes full responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. A. C., D. M. S., M. C., and D. A. G. contributed substantially to the study design, data analysis and interpretation, and writing of the manuscript.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST the following: A. C. has served as a consultant for Amgen, Bracco, and Genzyme and has received research support from Spark Therapeutics and T2 Biosystems. D. M. S. has participated in advisory boards for Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, and Portola Pharmaceuticals. D. A. G. has served as a consultant to Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Janssen, and Pfizer and has served as an investigator for Daiichi Sankyo and Janssen. None declared (B. T. S., M. C.).

Role of sponsors: The sponsor had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Additional information: The e-Tables can be found in the Supplemental Materials section of the online article.

Footnotes

FUNDING/SUPPORT: This research was supported in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [T32HL007093].

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Kearon C., Akl E.A., Comerota A.J., and the American College of Chest Physicians Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed—American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e419S–e494S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ansell J.E. Management of venous thromboembolism: clinical guidance from the Anticoagulation Forum. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;41(1):1–2. doi: 10.1007/s11239-015-1320-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.January C.T., Wann L.S., Alpert J.S. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2014;130(23):e199–e267. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Connolly S.J., Ezekowitz M.D., Yusuf S. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(12):1139–1151. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Granger C.B., Alexander J.H., McMurray J.J. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(11):981–992. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel M.R., Mahaffey K.W., Garg J. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(10):883–891. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giugliano R.P., Ruff C.T., Braunwald E. Edoxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(22):2093–2104. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin K., Moll S. Direct oral anticoagulant drug level testing in clinical practice: a single institution experience. Thromb Res. 2016;143:40–44. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2016.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cuker A., Siegal D.M., Crowther M.A. Laboratory measurement of the anticoagulant activity of the non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(11):1128–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.05.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ageno W., Gallus A.S., Wittkowsky A., Crowther M., Hylek E.M., Palareti G., and the American College of Chest Physicians Oral anticoagulant therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e44S–e88S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baglin T, Hillarp A, Tripodi A, et al. Measuring Oral Direct Inhibitors (ODIs) of thrombin and factor Xa: A recommendation from the Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation of the Scientific and Standardisation Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis [published online ahead of print January 24, 2013]. J Thromb Haemost.http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jth.12149. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Cuker A., Husseinzadeh H. Laboratory measurement of the anticoagulant activity of edoxaban: a systematic review. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2015;39(3):288–294. doi: 10.1007/s11239-015-1185-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stangier J., Clemens A. Pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of dabigatran etexilate, an oral direct thrombin inhibitor. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2009;15(suppl 1):9S–16S. doi: 10.1177/1076029609343004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Antovic J.P., Skeppholm M., Eintrei J. Evaluation of coagulation assays versus LC-MS/MS for determinations of dabigatran concentrations in plasma. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(11):1875–1881. doi: 10.1007/s00228-013-1550-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Avecilla S.T., Ferrell C., Chandler W.L. Plasma-diluted thrombin time to measure dabigatran concentrations during dabigatran etexilate therapy. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;137(4):572–574. doi: 10.1309/AJCPAU7OQM0SRPZQ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonar R., Favaloro E.J., Mohammed S. The effect of dabigatran on haemostasis tests: a comprehensive assessment using in vitro and ex vivo samples. Pathology. 2015;47(4):355–364. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0000000000000252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chin P.K., Patterson D.M., Zhang M. Coagulation assays and plasma fibrinogen concentrations in real-world patients with atrial fibrillation treated with dabigatran. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;78(3):630–638. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dager W.E., Gosselin R.C., Kitchen S. Dabigatran effects on the international normalized ratio, activated partial thromboplastin time, thrombin time, and fibrinogen: a multicenter, in vitro study. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46(12):1627–1636. doi: 10.1345/aph.1R179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delavenne X., Moracchini J., Laporte S. UPLC MS/MS assay for routine quantification of dabigatran—a direct thrombin inhibitor—in human plasma. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2012;58:152–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2011.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dias J.D., Norem K., Doorneweerd D.D. Use of thromboelastography (TEG) for detection of new oral anticoagulants. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139(5):665–673. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2014-0170-OA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dietrich K., Stang L., van Ryn J. Assessing the anticoagulant effect of dabigatran in children: an in vitro study. Thromb Res. 2015;135(4):630–635. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2015.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Douxfils J., Dogne J.M., Mullier F. Comparison of calibrated dilute thrombin time and aPTT tests with LC-MS/MS for the therapeutic monitoring of patients treated with dabigatran etexilate. Thromb Haemost. 2013;110(3):543–549. doi: 10.1160/TH13-03-0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Douxfils J., Mullier F., Robert S. Impact of dabigatran on a large panel of routine or specific coagulation assays: laboratory recommendations for monitoring of dabigatran etexilate. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107(5):985–997. doi: 10.1160/TH11-11-0804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gosselin R.C., Adcock D., Hawes E.M. Evaluating the use of commercial drug-specific calibrators for determining PT and APTT reagent sensitivity to dabigatran and rivaroxaban. Thromb Haemost. 2015;113(1):77–84. doi: 10.1160/TH14-04-0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gosselin R.C., Dwyre D.M., Dager W.E. Measuring dabigatran concentrations using a chromogenic ecarin clotting time assay. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(12):1635–1640. doi: 10.1177/1060028013509074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Halbmayer W.M., Weigel G., Quehenberger P. Interference of the new oral anticoagulant dabigatran with frequently used coagulation tests. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2012;50(9):1601–1605. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2011-0888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harenberg J., Giese C., Marx S. Determination of dabigatran in human plasma samples. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2012;38(1):16–22. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1300947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hartter S., Yamamura N., Stangier J. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in Japanese and Caucasian subjects after oral administration of dabigatran etexilate. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107(2):260–269. doi: 10.1160/TH11-08-0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hawes E.M., Deal A.M., Funk-Adcock D. Performance of coagulation tests in patients on therapeutic doses of dabigatran: a cross-sectional pharmacodynamic study based on peak and trough plasma levels. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11(8):1493–1502. doi: 10.1111/jth.12308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.He S., Wallen H., Bark N. In vitro studies using a global hemostasis assay to examine the anticoagulation effects in plasma by the direct thrombin inhibitors: dabigatran and argatroban. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2013;35(2):131–139. doi: 10.1007/s11239-012-0791-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones S.D., Eaddy N.S., Chan G.T. Dabigatran: laboratory monitoring. Pathology. 2012;44(6):578–580. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0b013e32835833f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liesenfeld K.H., Schaefer H.G., Troconiz I.F. Effects of the direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran on ex vivo coagulation time in orthopaedic surgery patients: a population model analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62(5):527–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02667.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lindahl T.L., Baghaei F., Blixter I.F. Effects of the oral, direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran on five common coagulation assays. Thromb Haemost. 2011;105(2):371–378. doi: 10.1160/TH10-06-0342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmohl M., Gansser D., Moschetti V. Measurement of dabigatran plasma concentrations by calibrated thrombin clotting time in comparison to LC-MS/MS in human volunteers on dialysis. Thromb Res. 2015;135(3):532–536. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2014.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sinigoj P., Malmstrom R.E., Vene N. Dabigatran concentration: variability and potential bleeding prediction in “real-life” patients with atrial fibrillation. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;117(5):323–329. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.12417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skeppholm M., Hjemdahl P., Antovic J.P. On the monitoring of dabigatran treatment in “real life” patients with atrial fibrillation. Thromb Res. 2014;134(4):783–789. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2014.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stangier J., Feuring M. Using the HEMOCLOT direct thrombin inhibitor assay to determine plasma concentrations of dabigatran. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2012;23(2):138–143. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e32834f1b0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stangier J., Rathgen K., Stahle H. The pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and tolerability of dabigatran etexilate, a new oral direct thrombin inhibitor, in healthy male subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;64(3):292–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02899.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stangier J., Stahle H., Rathgen K. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the direct oral thrombin inhibitor dabigatran in healthy elderly subjects. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2008;47(1):47–59. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200847010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Blerk M., Bailleul E., Chatelain B. Influence of dabigatran and rivaroxaban on routine coagulation assays: a nationwide Belgian survey. Thromb Haemost. 2015;113(1):154–164. doi: 10.1160/TH14-02-0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Ryn J., Baruch L., Clemens A. Interpretation of point-of-care INR results in patients treated with dabigatran. Am J Med. 2012;125(4):417–420. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Douxfils J., Lessire S., Dincq A.S. Estimation of dabigatran plasma concentrations in the perioperative setting: an ex vivo study using dedicated coagulation assays. Thromb Haemost. 2015;113(4):862–869. doi: 10.1160/TH14-09-0808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eller T., Busse J., Dittrich M. Dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, argatroban and fondaparinux and their effects on coagulation POC and platelet function tests. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2014;52(6):835–844. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2013-0936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilson J.A., Goralski K.B., Soroka S.D. An evaluation of oral dabigatran etexilate pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in hemodialysis. J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;54(8):901–909. doi: 10.1002/jcph.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Douxfils J., Chatelain B., Hjemdahl P. Does the Russell viper venom time test provide a rapid estimation of the intensity of oral anticoagulation? A cohort study. Thromb Res. 2015;135(5):852–860. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2015.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dinkelaar J., Molenaar P.J., Ninivaggi M. In vitro assessment, using thrombin generation, of the applicability of prothrombin complex concentrate as an antidote for rivaroxaban. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11(6):1111–1118. doi: 10.1111/jth.12236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meyer Dos Santos S., Zorn A., Guttenberg Z. A novel μ-fluidic whole blood coagulation assay based on Rayleigh surface-acoustic waves as a point-of-care method to detect anticoagulants. Biomicrofluidics. 2013;7(5):56502. doi: 10.1063/1.4824043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Helin T.A., Pakkanen A., Lassila R. Laboratory assessment of novel oral anticoagulants: method suitability and variability between coagulation laboratories. Clin Chem. 2013;59(5):807–814. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.198788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Perzborn E., Strassburger J., Wilmen A. In vitro and in vivo studies of the novel antithrombotic agent BAY 59-7939: an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(3):514–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bayer Inc. Product Monograph: PrXarelto. http://omr.bayer.ca/omr/online/xarelto-pm-en.pdf. Accessed October 12, 2015.

- 51.Kubitza D., Becka M., Voith B. Safety, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics of single doses of BAY 59-7939, an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;78(4):412–421. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kubitza D., Becka M., Wensing G. Safety, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics of BAY 59-7939—an oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor—after multiple dosing in healthy male subjects. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;61(12):873–880. doi: 10.1007/s00228-005-0043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Burghaus R., Coboeken K., Gaub T. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban using a computer model for blood coagulation. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e17626. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weinz C., Schwarz T., Kubitza D. Metabolism and excretion of rivaroxaban, an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor, in rats, dogs, and humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37(5):1056–1064. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.025569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Adelmann D., Wiegele M., Wohlgemuth R.K. Measuring the activity of apixaban and rivaroxaban with rotational thrombelastometry. Thromb Res. 2014;134(4):918–923. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arachchillage D.R., Mackie I.J., Efthymiou M. Interactions between rivaroxaban and antiphospholipid antibodies in thrombotic antiphospholipid syndrome. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(7):1264–1273. doi: 10.1111/jth.12917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Asmis L.M., Alberio L., Angelillo-Scherrer A. Rivaroxaban: quantification by anti-FXa assay and influence on coagulation tests—a study in 9 Swiss laboratories. Thromb Res. 2012;129(4):492–498. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Attard C., Monagle P., Kubitza D. The in vitro anticoagulant effect of rivaroxaban in children. Thromb Res. 2012;130(5):804–807. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Attard C., Monagle P., Kubitza D. The in-vitro anticoagulant effect of rivaroxaban in neonates. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2014;25(3):237–240. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0000000000000033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barrett Y.C., Wang Z., Frost C. Clinical laboratory measurement of direct factor Xa inhibitors: anti-Xa assay is preferable to prothrombin time assay. Thromb Haemost. 2010;104(6):1263–1271. doi: 10.1160/TH10-05-0328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dale B.J., Ginsberg J.S., Johnston M. Comparison of the effects of apixaban and rivaroxaban on prothrombin and activated partial thromboplastin times using various reagents. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12(11):1810–1815. doi: 10.1111/jth.12720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Douxfils J., Mullier F., Loosen C. Assessment of the impact of rivaroxaban on coagulation assays: laboratory recommendations for the monitoring of rivaroxaban and review of the literature. Thromb Res. 2012;130(6):956–966. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Douxfils J., Tamigniau A., Chatelain B. Comparison of calibrated chromogenic anti-Xa assay and PT tests with LC-MS/MS for the therapeutic monitoring of patients treated with rivaroxaban. Thromb Haemost. 2013;110(4):723–731. doi: 10.1160/TH13-04-0274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Du S., Harenberg J., Krämer S., Krämer R., Wehling M., Weiss C. Measurement of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in patient plasma using Heptest-STAT coagulation method. Ther Drug Monit. 2015;37(3):375–380. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0000000000000157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Du S., Kramer S., Giese C. Chromogenic assays for measurement of rivaroxaban from EDTA anticoagulated plasma samples. Thromb Haemost. 2015;113(5):1149–1151. doi: 10.1160/TH14-10-0869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Francart S.J., Hawes E.M., Deal A.M. Performance of coagulation tests in patients on therapeutic doses of rivaroxaban: a cross-sectional pharmacodynamic study based on peak and trough plasma levels. Thromb Haemost. 2014;111(6):1133–1140. doi: 10.1160/TH13-10-0871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Frost C., Song Y., Barrett Y.C. A randomized direct comparison of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of apixaban and rivaroxaban. Clin Pharmacol. 2014;6:179–187. doi: 10.2147/CPAA.S61131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gerotziafas G.T., Baccouche H., Sassi M. Optimisation of the assays for the measurement of clotting factor activity in the presence of rivaroxaban. Thromb Res. 2012;129(1):101–103. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gerotziafas G.T., Elalamy I., Depasse F. In vitro inhibition of thrombin generation, after tissue factor pathway activation, by the oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor rivaroxaban. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(4):886–888. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Girgis I.G., Patel M.R., Peters G.R. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of rivaroxaban in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation: results from ROCKET AF. J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;54(8):917–927. doi: 10.1002/jcph.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gosselin R.C., Adcock Funk D.M., Taylor J.M. Comparison of anti-Xa and dilute Russell viper venom time assays in quantifying drug levels in patients on therapeutic doses of rivaroxaban. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138(12):1680–1684. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2013-0750-OA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gosselin R.C., Francart S.J., Hawes E.M. Heparin-calibrated chromogenic anti-Xa activity measurements in patients receiving rivaroxaban: can this test be used to quantify drug level? Ann Pharmacother. 2015;49(7):777–783. doi: 10.1177/1060028015578451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Harder S., Parisius J., Picard-Willems B. Monitoring direct FXa-inhibitors and fondaparinux by Prothrombinase-induced Clotting Time (PiCT): relation to FXa-activity and influence of assay modifications. Thromb Res. 2008;123(2):396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Harenberg J., Kramer R., Giese C. Determination of rivaroxaban by different factor Xa specific chromogenic substrate assays: reduction of interassay variability. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2011;32(3):267–271. doi: 10.1007/s11239-011-0622-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Harenberg J., Marx S., Kramer R. Determination of an international sensitivity index of thromboplastin reagents using a WHO thromboplastin as calibrator for plasma spiked with rivaroxaban. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2011;22(8):637–641. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e328349f1d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hillarp A., Baghaei F., Fagerberg Blixter I. Effects of the oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor rivaroxaban on commonly used coagulation assays. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(1):133–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jourdi G., Siguret V., Martin A.C. Association rate constants rationalise the pharmacodynamics of apixaban and rivaroxaban. Thromb Haemost. 2015;114(1):78–86. doi: 10.1160/TH14-10-0877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kluft C., Meijer P., Kret R. Preincubation in the Prothrombinase-induced Clotting Time test (PiCT) is necessary for in vitro evaluation of fondaparinux and to be avoided for the reversible, direct factor Xa inhibitor, rivaroxaban. Int J Lab Hematol. 2013;35(4):379–384. doi: 10.1111/ijlh.12027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Korber M.K., Langer E., Ziemer S. Measurement and reversal of prophylactic and therapeutic peak levels of rivaroxaban: an in vitro study. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2014;20(7):735–740. doi: 10.1177/1076029613494468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Molenaar P.J., Dinkelaar J., Leyte A. Measuring rivaroxaban in a clinical laboratory setting, using common coagulation assays, Xa inhibition and thrombin generation. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2012;50(10):1799–1807. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2012-0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mueck W., Becka M., Kubitza D. Population model of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of rivaroxaban—an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor—in healthy subjects. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;45(6):335–344. doi: 10.5414/cpp45335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mueck W., Borris L.C., Dahl O.E. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of once- and twice-daily rivaroxaban for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in patients undergoing total hip replacement. Thromb Haemost. 2008;100(3):453–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mueck W., Eriksson B.I., Bauer K.A. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of rivaroxaban—an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor—in patients undergoing major orthopaedic surgery. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2008;47(3):203–216. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200847030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mueck W., Lensing A.W., Agnelli G. Rivaroxaban: population pharmacokinetic analyses in patients treated for acute deep-vein thrombosis and exposure simulations in patients with atrial fibrillation treated for stroke prevention. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2011;50(10):675–686. doi: 10.2165/11595320-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Novak M., Schlagenhauf A., Bernhard H. Effect of rivaroxaban, in contrast to heparin, is similar in neonatal and adult plasma. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2011;22(7):588–592. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e328349f190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rathbun S., Tafur A., Grant R. Comparison of methods to determine rivaroxaban anti-factor Xa activity. Thromb Res. 2015;135(2):394–397. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2014.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Samama M.M., Contant G., Spiro T.E. Evaluation of the prothrombin time for measuring rivaroxaban plasma concentrations using calibrators and controls: results of a multicenter field trial. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2012;18(2):150–158. doi: 10.1177/1076029611426282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Samama M.M., Contant G., Spiro T.E. Evaluation of the anti-factor Xa chromogenic assay for the measurement of rivaroxaban plasma concentrations using calibrators and controls. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107(2):379–387. doi: 10.1160/TH11-06-0391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Samama M.M., Martinoli J.L., LeFlem L. Assessment of laboratory assays to measure rivaroxaban: an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor. Thromb Haemost. 2010;103(4):815–825. doi: 10.1160/TH09-03-0176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tripodi A., Chantarangkul V., Guinet C. The International Normalized Ratio calibrated for rivaroxaban has the potential to normalize prothrombin time results for rivaroxaban-treated patients: results of an in vitro study. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(1):226–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wolzt M., Gouya G., Kapiotis S. Open-label, randomized study of the effect of rivaroxaban with or without acetylsalicylic acid on thrombus formation in a perfusion chamber. Thromb Res. 2013;132(2):240–247. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2013.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Xu X.S., Moore K., Burton P. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of rivaroxaban in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;74(1):86–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04181.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mani H., Rohde G., Stratmann G. Accurate determination of rivaroxaban levels requires different calibrator sets but not addition of antithrombin. Thromb Haemost. 2012;108(1):191–198. doi: 10.1160/TH11-12-0832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Frost C., Nepal S., Wang J. Safety, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of multiple oral doses of apixaban, a factor Xa inhibitor, in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;76(5):776–786. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Eliquis [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2012. http://packageinserts.bms.com/pi/pi_eliquis.pdf. Accessed September 14, 2015.

- 96.Barrett Y.C., Wang Z., Knabb R.M. A novel prothrombin time assay for assessing the anticoagulant activity of oral factor Xa inhibitors. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2013;19(5):522–528. doi: 10.1177/1076029612441859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Becker R.C., Yang H., Barrett Y. Chromogenic laboratory assays to measure the factor Xa-inhibiting properties of apixaban: an oral, direct and selective factor Xa inhibitor. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2011;32(2):183–187. doi: 10.1007/s11239-011-0591-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gouin-Thibault I., Flaujac C., Delavenne X. Assessment of apixaban plasma levels by laboratory tests: suitability of three anti-Xa assays—a multicentre French GEHT study. Thromb Haemost. 2014;111(2):240–248. doi: 10.1160/TH13-06-0470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Skeppholm M., Al-Aieshy F., Berndtsson M. Clinical evaluation of laboratory methods to monitor apixaban treatment in patients with atrial fibrillation. Thromb Res. 2015;136(1):148–153. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2015.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Martin A.C., Gouin-Thibault I., Siguret V. Multimodal assessment of non-specific hemostatic agents for apixaban reversal. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(3):426–436. doi: 10.1111/jth.12830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tripodi A., Padovan L., Veena C. How the direct oral anticoagulant apixaban affects thrombin generation parameters. Thromb Res. 2015;135(6):1186–1190. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2015.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Weitz J.I., Connolly S.J., Patel I. Randomised, parallel-group, multicentre, multinational phase 2 study comparing edoxaban, an oral factor Xa inhibitor, with warfarin for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation. Thromb Haemost. 2010;104(3):633–641. doi: 10.1160/TH10-01-0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fukuda T., Honda Y., Kamisato C. Reversal of anticoagulant effects of edoxaban, an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor, with haemostatic agents. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107(2):253–259. doi: 10.1160/TH11-09-0668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Furugohri T., Isobe K., Honda Y. DU-176b, a potent and orally active factor Xa inhibitor: in vitro and in vivo pharmacological profiles. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6(9):1542–1549. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Furugohri T., Sugiyama N., Morishima Y. Antithrombin-independent thrombin inhibitors, but not direct factor Xa inhibitors, enhance thrombin generation in plasma through inhibition of thrombin-thrombomodulin-protein C system. Thromb Haemost. 2011;106(6):1076–1083. doi: 10.1160/TH11-06-0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Honda Y., Morishima Y. Thrombin generation induced by tissue factor plus ADP in human platelet rich plasma: a potential new measurement to assess the effect of the concomitant use of an oral factor Xa inhibitor edoxaban and P2Y12 receptor antagonists. Thromb Res. 2015;135(5):958–962. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mendell J., Noveck R.J., Shi M. A randomized trial of the safety, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of edoxaban, an oral factor Xa inhibitor, following a switch from warfarin. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;75(4):966–978. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mendell J., Tachibana M., Shi M. Effects of food on the pharmacokinetics of edoxaban, an oral direct factor Xa inhibitor, in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;51(5):687–694. doi: 10.1177/0091270010370974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Morishima Y., Kamisato C. Laboratory measurements of the oral direct factor Xa inhibitor edoxaban: comparison of prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, and thrombin generation assay. Am J Clin Pathol. 2015;143(2):241–247. doi: 10.1309/AJCPQ2NJD3PXFTUG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Noguchi K., Morishima Y., Takahashi S. Impact of nonsynonymous mutations of factor X on the functions of factor X and anticoagulant activity of edoxaban. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2015;26(2):117–122. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0000000000000147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ogata K., Mendell-Harary J., Tachibana M. Clinical safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of the novel factor Xa inhibitor edoxaban in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;50(7):743–753. doi: 10.1177/0091270009351883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ruff C.T., Giugliano R.P., Braunwald E. Association between edoxaban dose, concentration, anti-Factor Xa activity, and outcomes: an analysis of data from the randomised, double-blind ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9984):2288–2295. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61943-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Samama M.M., Mendell J., Guinet C. In vitro study of the anticoagulant effects of edoxaban and its effect on thrombin generation in comparison to fondaparinux. Thromb Res. 2012;129(4):e77–e82. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wolzt M., Samama M.M., Kapiotis S. Effect of edoxaban on markers of coagulation in venous and shed blood compared with fondaparinux. Thromb Haemost. 2011;105(6):1080–1090. doi: 10.1160/TH10-11-0705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Zafar M.U., Vorchheimer D.A., Gaztanaga J. Antithrombotic effects of factor Xa inhibition with DU-176b: phase-I study of an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor using an ex-vivo flow chamber. Thromb Haemost. 2007;98(4):883–888. doi: 10.1160/th07-04-0312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Favaloro E.J., Bonar R., Butler J. Laboratory testing for the new oral anticoagulants: a review of current practice. Pathology. 2013;45(4):435–437. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0b013e328360f02d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Zantek N.D., Hayward C.P., Simcox T.G., Smock K.J., Hsu P., Van Cott E.M. An assessment of the state of current practice in coagulation laboratories. Am J Clin Pathol. 2016;146(3):378–383. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqw121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Pathologists CoA. Surveys Participant Summary for CGE, CGL, GCS, and ACM. College of American Pathologists, Northfield, IL. 2013.

- 119.Pathologists CoA. Anticoagulant Monitoring Dabigatran, Fondaparinux and Rivaroxaban. ACM-A 2016 Participant Summary. 2016.

- 120.Ezekowitz M.D., Reilly P.A., Nehmiz G. Dabigatran with or without concomitant aspirin compared with warfarin alone in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (PETRO Study) Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(9):1419–1426. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.van Ryn J., Stangier J., Haertter S. Dabigatran etexilate: a novel, reversible, oral direct thrombin inhibitor—interpretation of coagulation assays and reversal of anticoagulant activity. Thromb Haemost. 2010;103(6):1116–1127. doi: 10.1160/TH09-11-0758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.