1. Background

Epilepsy is a complex disorder that can be challenging to manage. Social support confers a number of advantages on health and well-being [1,2]. Supportive relationships might help people with chronic disorders like epilepsy better manage their disorder and improve quality of life [3,4]. Little is known about household or family structure for adults living with epilepsy. This brief report uses two nationally representative samples to compare the various household/family structures of adults with and without epilepsy.

2. Methods

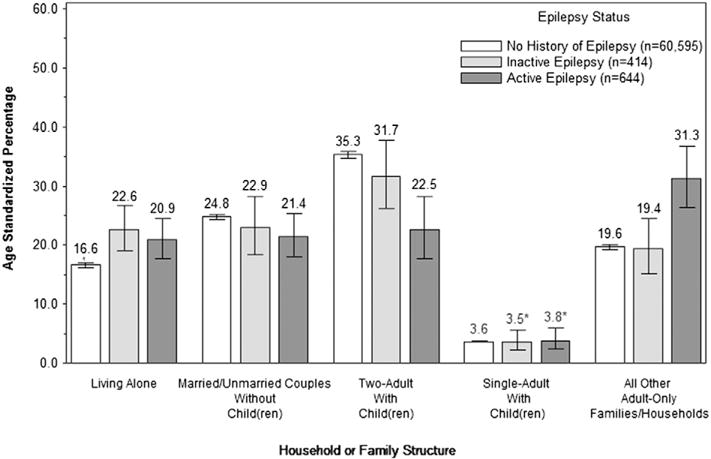

For adults with active epilepsy, inactive epilepsy, and no epilepsy, this report compares the age-standardized prevalence in the combined 2010 and 2013 cross-sectional National Health Interview Surveys of five types of household or family structures (living alone, married/unmarried couples without child(ren), two-adult with child(ren), single-adult with child(ren), and all other adult-only households).

3. Results

The percentages who reported living alone were significantly higher for adults with active epilepsy (20.9%) or inactive epilepsy (22.6%) than that of adults without epilepsy (16.6%; Fig. 1). The percentage who reported living in two-adult households/families with child(ren) was significantly lower in adults with active epilepsy (22.5%) than that in adults without epilepsy (35.3%). The percentage who reported living in all other adults-only households/families was significantly higher in adults with active epilepsy (31.3%) than that in those without epilepsy (19.6%).

Fig. 1.

Age-standardized1 percentage distribution of household or family structure2 for adults (18 years and above) by epilepsy status3—National Health Interview Survey4, United States, 2010 and 2013. Notes: ¶95% confidence interval for age-standardized percentage of each point estimate shown in the graph. *These estimates are unreliable because they have relative standard errors (RSE) ≥20% and b30%. 1Estimates are age-standardized (18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65+) using the projected 2000 US population as the standard population. 2Family structure is measured by an NHIS-recoded variable with 13 mutually exclusive response values that take into account parental marital status and the type of relationship (e.g., biological, adoptive, step-) between children aged 0–17 years and any parents present in the family. Because of the small sample sizes of some of these responses, we combined and further recoded them into five levels. For example, married/unmarried couples include both married and unmarried couples without any children. Two-adult households/families with child(ren) consist of five categories: parents with child(ren), one parent and one step-parent with child(ren), one parent and one cohabiting partner with child(ren), at least one parent and other related adults with child(ren), and other related and/or unrelated adults with child(ren). Single-adult households/families include responses of mother with child(ren) only, father with child(ren) only, and all other single-adult with child(ren) categories. All other adult-only households/families include categories of all other adult-only families and living with roommate(s). 3Epilepsy status is measured based on responses to three questions, 1). “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you have a seizure disorder or epilepsy?”; 2). “Are you currently taking any medicine to control your seizure disorder or epilepsy?”; and 3). “Today is [fill: Current Date]. Think back to last year about the same time. About how many seizures of any type have you had in the past year.” Adults who responded “No” to the first question were considered as having no history of epilepsy. Respondents who answered “Yes” to the first question, “no” or “do not know” to the second question, and reported having zero seizures during the past year for the third question were considered as having inactive epilepsy. Adults who answered “yes” to the first two questions or if they reported one or more seizures during the past year in response to the third question were considered as having active epilepsy. The case-ascertainment questions and case-classification definitions follow standards for epidemiologic studies of epilepsy and have acceptable positive predictive value for identifying clinical cases of epilepsy [5]. 4Estimates are based on household interviews of a nationally representative sample of the noninstitutionalized U.S. civilian population and are derived from the National Health Interview Survey. This analysis used the sample adult, person, and family files and was weighted using sample adult weight. Complex survey design was also accounted for.

4. Conclusion

Among adults with active epilepsy, one in five lives alone and less than one in four live in households with two adults and children. More adults with active epilepsy live in multi-person households than those without the disorder. Adults with epilepsy living alone may be at increased risk of injury associated with uncontrolled seizures, mental distress associated with social isolation, lower quality of life, and early mortality [6,7]. Adults with epilepsy who live in single-adult households with children face the same and added care-giving stress that might complicate their disorder. Epilepsy providers should consider household or family structure as a health determinant. Ensuring that these two groups of adults with epilepsy have access to instrumental and emotional resources is paramount. Further study assessing the type and quality of supportive relationships in other family structures for adults with epilepsy is also warranted.

Acknowledgments

The findings and conclusions in this study are those of the (corresponding) authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Cohen S, Syme L. Social support and health. Orlando, FL: Academic Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berkman L. The role of social relations in health promotion. Psychosom Med. 1995;57:245–54. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199505000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amir M, Roziner I, Knoll A, Neufeld MY. Self-efficacy and social support as mediators in the relation between disease severity and quality of life in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1999;40:216–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb02078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vassilev I, Rogers A, Sanders C, Kennedy A, Blickem C, Protheroe J, et al. Social networks, social capital and chronic illness self-management: a realist review. Chronic Illn. 2011;7:60–86. doi: 10.1177/1742395310383338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooks DR, Avetisyan R, Jarrett KM, Hanchate A, Shapiro G, Pugh M, et al. Validation of self-reported epilepsy for purposes of community surveillance. Epilepsy Behav. 2012;23:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barger SD, Messerli-Bürgy N, Barth J. Social relationship correlates of major depressive disorder and depressive symptoms in Switzerland: nationally representative cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:273–83. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]