Highlights

-

•

Inflammatory pseudotumor is a very rare benign neoplasm.

-

•

Definitive diagnosis is usually made only after surgery.

-

•

Mesenteric location is rare.

-

•

Surgical resection can cure the disease.

-

•

Close follow-up is advised to identify recurrences.

Keywords: Inflammatory pseudotumor, Diagnosis, Mesenteric location, Case report, Follow-up

Abstract

Introduction

Inflammatory pseudotumor (IP) is an uncommon benign neoplasm. It was first described in the lung but it has been recognized in several somatic and visceral locations. Mesenteric presentation is rare and its clinical presentation is variable but patients can be completely asymptomatic. Complete surgical resection is the only curable treatment. Rational follow-up protocols have not been established yet.

Presentation of case

A 57 years-old man, with no relevant comorbidities and completely asymptomatic, apart from a lump on the right hypochondrium, was submitted to surgical resection of a large mesenteric mass. The preoperative Computed Tomography suggested gastrointestinal stromal tumor as the most probable diagnosis. Definitive histological examination of the completely resected surgical specimen confirmed the diagnosis of IP. The patient has been on follow-up for four years, without no evidence of recurrence.

Discussion

The preoperative diagnosis of IP may be difficult to establish mainly due to the lack of a typical clinical presentation. It is a rare entity, particularly in the adult population. These two aspects make it easier to neglect this entity in the differential diagnosis of an abdominal mass on asymptomatic adults. Although there are no formal guidelines on follow-up, close follow-up seems to be advisable in these patients as recurrence is frequent.

Conclusion

IP should be present as a possible differential diagnosis in an abdominal mass. Complete excision of the lesion can be curable but close follow-up seems to be required.

1. Introduction

The present work has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria [1].

Inflammatory pseudotumour (IP) is a rare benign neoplasm firstly described by Brunn in 1939 [2]. It was first described in the lung but it has been recognized in several somatic and visceral locations [3]. Since its first description, several other terms have been used to address this lesion, such as postinflammatory pseudotumour, cellular inflammatory pseudotumour, plasma cell pseudotumour, plasma cell granuloma, inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour, inflammatory myohistiocytic proliferation, inflammatory myohistiocytic tumour, inflammatory pseudosarcomatous proliferation, inflammatory fibrosarcoma, myofibroblastoma, fibrous histiocytoma, histiocytoma, solitary xanthoma, xanthogranuloma, fibroxantholoma, omental-mesenteric myxoid hamartoma, pulmonary plasmocytoma, mast cell tumour [4].

IP is a lesion composed of inflammatory cells and myofibroblastic spindle cells which can pose, on the preoperative setting, a difficult differential diagnosis with malignacy [2].

Its exact etiology is largely unknown, but it may be related to with minor trauma, surgery, other malignancy or even previous infection [2], [5].

Clinical presentation is quite unspecific, as fever, weight loss, malaise and/or abdominal pain may be present. Non-specific laboratory results may be present [3], [6].

IPs can be hardly distinguished from other tumors on radiologic exams, making histologic analysis mandatory to establish the diagnosis [7].

Despite its usual benign clinical behavior, IPs can turn out to be aggressive and recurrent [3]. To the best of our knowledge, no definitive guidelines to manage these tumors are yet established, but complete surgical resection stands as the optimal curable treatment [8].

2. Case report

A 57 years-old patient, with no relevant medical or surgical history and completely asymptomatic, was sent to our General Surgery Department after performing an abdominal contrasted computed tomography (CT) for the evaluation of a mass on the right hypochondrium. On physical examination, one could see and palpate a voluminous and indurated, yet mobile, mass.

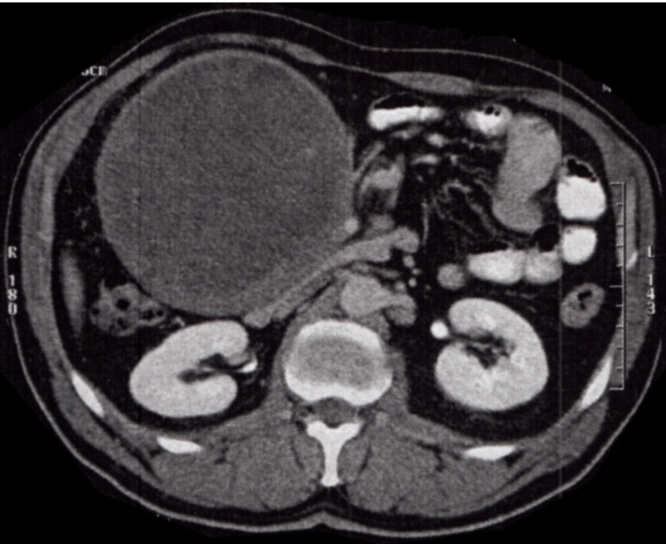

The CT showed a single, round, 14 × 12,5 cm mass, with heterogeneous density (some small calcifications and hypodense areas), thick-walled, which compressed several intestinal loops, the uncinate process of the pancreas and also the third portion of the duodenum. It also seemed to be adherent to the third portion of the duodenum and to the gastric antrum, and a slight mesenteric densification was also present. At that point, Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor (GIST) was the most probable diagnosis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Voluminous mass on the abdominal CT image.

Laboratory results were unremarkable: Hemoglobin: 15.5 g/dl, Hematocrit: 45,8%, White Blood Cell count: 7.900/mm, Platelets: 181.000/mm and normal Creatinine, Alanine Aminotransferase and Aspartate Aminotransferase levels. Tumor markers (Alfa-fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigen 19-9 and carbohydrate antigen 125) were also within the normal range of values.

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration of the mass was attempted. Nevertheless, mainly due to the notorious wall thickness, extraction of biological material for histological examination was not possible.

Taking into account that GIST was the most probable diagnosis, the patient underwent surgery, first by a laparoscopic approach and posteriorly converted to laparotomy in an attempt to completely resect the mass. A huge and well vascularized mass was found, which was adjacent to the second and third portions of the duodenum, transverse colon, body of the pancreas, and to the superior mesenteric artery and vein. Further exploration allowed to preserve these blood vessels, but a segmental colectomy of the transverse colon and a primary anastomosis needed to be performed as result of ischemia (Fig. 2). Intraoperative extemporaneous examination was performed, confirming the absence of malignancy (Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

Aspect of the 14 × 14 × 10 cm mesenteric IP.

Fig. 3.

Macroscopic aspect of the 1245 g IP.

Fig. 4.

IP with cavitary disintegration and necrosis.

Definitive histology revealed a 1245 g and 14 × 14 × 10 cm mesenteric inflammatory pseudotumor, with associated ischemia, cavitary disintegration and almost complete necrosis.

The patient was discharged on the fifteenth postoperative day with no relevant morbidity. After a four-years follow-up, there is no clinical or imagiological evidence of recurrence.

3. Discussion

Preoperative diagnosis of IP can be troublesome to establish, mainly due to the lack of a typical clinical presentation.

In the literature, some retrospective reviews have been published in the pediatric population [9] whereas in adults only small series have been reported, making IP a rare entity [10]. IP can occur in nearly any organ of the human body, with the lung and the orbit being the more commonly affected ones [2], [8]. Even in children, abdominal IPs are not usual and diagnosis is usually made after surgical resection [6].

Both local and systemic symptoms can be caused by the production of interleukin 1 or interleukin 6 by monocytes and macrophages [2], [3]. Symptoms can be present in up to 15%-30% of the patients and are usually mild and non-specific, such as malaise, fever or weight loss. Site-related symptoms, like abdominal pain or jaundice may be present when the location of the neoplasm is within the peritoneal cavity. Usual laboratory findings are hypochromic microcytic anemia, thrombocytosis, leukocytosis, hypergammaglobulinemia and an elevated sedimentation rate [3], [6].

The case of a previously healthy 57 years-old man who was completely asymptomatic and whose only complaint was the mass he felt on the right hypochondrium is herein presented. CT was performed and GIST was the most probable preoperative diagnosis.

Due to the lack of symptoms, the normality of the laboratory tests results and the adherence of the lesion to structures such as the duodenum and pancreas, further study of the mass with an endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration was attempted. Unfortunately, the calcified wall of the tumor prevented its realization. Was it successful, it would probably consist mostly of myofibroblastic cells which could help exclude other possible differential diagnosis [2].

The radiological characteristics of IP on the CT scans are variable, ranging from nonenhancement to heterogeneous or peripheral enhancement. A central calcification may also be present. Larger lesions can present with necrosis, which is translated into a hypodense image [2], [8]. Some authors have already described the correlation between anatomic findings and Magnetic Resonance Imaging, as mesenteric IPs show an intermediate signal on T1-weighted imaging and a heterogeneous one on T2-weighted imaging with variable contrast enhancement [11].

Performing a fine-needle biopsy was not possible, due to the calcification of the mass wall. Nevertheless, such could fail to obtain sufficient volume of tumor tissue for making a definitive diagnosis [12].

The recurrence rates after surgical resection of abdominal IPs are usually high (up to 25%), mainly because of often incomplete excision of the mass [12]. The tumor is often curable with surgical excision, close follow-up and re-excision even in cases of multiple recurrence [6]. Metastatic lesions are present in less than 5% of the cases [12].

In this case the complete removal of the mass was achieved, although a partial resection of the transverse colon was needed due to the loss of its vascularization. Nevertheless, such allowed a complete mass resection and, four years after the surgery, we have found no evidence of recurrence.

Differential diagnosis of this entity is difficult. Nevertheless, one should be aware of its existence, as its recognition is important to avoid unnecessary radical surgery [13].

The are no standardized follow-up protocols established for this entity. The rarity of this disease and the different terms used literature reports make it more difficult to compare follow-up and treatment results.

As the highest risk of recurrence appears to occur during the first year after surgery (15–37%) [8] and because a re-excision could prove curative6, we opted for an aggressive follow-up strategy, consisting of clinical evaluation (with special interest in general condition and gastrointestinal symptoms), laboratory tests − which include red and white blood cell count, hepatic enzymes and bilirubin − and a CT scan every 6 months for four years.

We have also decided that the patient would be kept in follow-up for a total of 5 years, as if it was a malignant tumor, due to some literature reports of sarcomatous degeneration after recurrence [4].

4. Conclusion

IP should be considered as a possible differential diagnosis in an abdominal mass, in order to avoid unnecessary radical surgery. Nevertheless, definitive diagnosis is usually established only after surgery. Whenever possible, care must be taken to completely remove the mass, as it can prove curable. In our case report, an aggressive follow-up strategy was adopted, bearing in mind that an early detection of a possible recurrence would probably allow its re-excision and lead to cure.

Conflicts of interest

There is no conflict of interest to be declared.

Funding

No source to be stated.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent

Informed consent for the publication of this work has been taken by the patient.

Author contribution

-

•

Vítor Neves Lopes: wrote the manuscript and follow-up.

-

•

César Alvarez: operated the patient, took the photographs and reviewed the manuscript.

-

•

M. Jesus Dantas: surgeon responsible for the in-patient optimization and reviewed the manuscript.

-

•

Carla Freitas: surgeon who operated the patient, follow-up and review the manuscript.

-

•

João Pinto-de-Sousa: reviewed the manuscript.

Guarantor

João Pinto-de-Sousa.

References

- 1.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S. Orgill DP, for the SCARE Group. The SCARE Statement: Consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Narla L.D., Newman B., Spottswood S.S., Narla S., Kolli R. Inflammatory pseudotumor. Radiographics. 2003;23(3):719–729. doi: 10.1148/rg.233025073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coffin C.M., Humphrey P.A., Dehner L.P. Extrapulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: a clinical and pathological survey. Semin. Diagn. Pathol. 1998;15:85–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaughan K.G., Aziz A., Meza M.P., Hackam D.J. Mesenteric inflammatory pseudotumor as a cause of abdominal pain in a teenager: presentation and literature review. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2005;21(6):497–499. doi: 10.1007/s00383-005-1395-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanders B.M., West K.W., Gingalewski C., Engum S., Davis M., Grosfeld J.L. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the alimentary tract: clinical and surgical experience. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2001;36:169–173. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.20045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mirshemirani A., Tabari A.K., Sadeghian N., Shariat-Torbaghan S., Pourafkari M., Mohajerzadeh L. Abdominal inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: report on four cases and review of literature. Iran. J. Pediatr. 2011;21(December (4)):543–548. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ko S.W., Shin S.S., Jeong Y.Y. Mesenteric inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor mimicking a necrotized malignant mass in an adult: case report with MR findings. Abdom. Imaging. 2005;30:616–619. doi: 10.1007/s00261-004-0296-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patnana M., Sevrukov A.B., Elsayes K.M., Viswanathan C., Lubner M., Menias C.O. Inflammatory pseudotumor: the great mimicker. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2012;198(March (3)):217–227. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dalton B.G., Thomas P.G., Sharp N.E., Manalang M.A., Fisher J.E., Moir C.R., St Peter S.D., Iqbal C.W. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors in children. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2016;51(April (4)):541–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yagmur Y., Akbulut S., Gumus S. Mesenteric inflammatory pseudotumor: a case report and comprehensive literature review. J. Gastrointest. Cancer. 2014;45(December (4)):414–420. doi: 10.1007/s12029-014-9642-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirchgesner T., Danse E., Sempoux Ch Annet L., Dragean ChA. Trefois P., Abbes Orabi N., Kartheuser A. Mesenteric inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: MRI and CT imaging correlated to anatomical pathology. JBR-BTR. 2014;97(5):301–302. doi: 10.5334/jbr-btr.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gleason B.C., Hornick J.L. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumours: where are we now? J. Clin. Pathol. 2008;61:428–437. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2007.049387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scott L., Blair G., Taylor G., Dimmick J. Fraser G..Inflammatory pseudotumors in children. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1988;23:755–758. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(88)80419-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]