Abstract

Postmortem magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is emerging as a valuable tool to accompany traditional autopsy and has potential for use in cases when traditional autopsy is not possible. This case report will review the use of postmortem MRI with limited tissue sampling to differentiate between metastatic neuroblastoma and hepatoblastoma which could not be clearly differentiated with prenatal ultrasound, prenatal MRI, or emergent postnatal ultrasound. The mother presented to our institution at 27 weeks gestation after an obstetric ultrasound at her obstetrician's office identified a large abdominal mass. Fetal ultrasonography and MRI confirmed the mass but were unable to differentiate between neuroblastoma and multifocal hepatoblastoma. The baby was delivered by cesarean section after nonreassuring heart tones led to an emergent cesarean section. The baby underwent decompressive laparotomy to relieve an abdominal compartment syndrome; however, the family eventually decided to withdraw life support. At this time, we performed a whole body postmortem MRI which further characterized the mass as an adrenal neuroblastoma which was confirmed with limited tissue sampling. Postmortem MRI was especially helpful in this case, as the patient’s family declined traditional autopsy.

Keywords: Fetal imaging, Postmortem imaging, MRI, Metastatic neuroblastoma, Virtual autopsy

Introduction

Postmortem magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is emerging as a valuable tool to accompany traditional autopsy. This case report will review the use of postmortem MRI with limited tissue sampling to differentiate between metastatic neuroblastoma and hepatoblastoma which could not be clearly differentiated with prenatal ultrasound, prenatal MRI, or emergent postnatal ultrasound. Postmortem MRI was especially helpful in this case, as the patient’s family declined traditional autopsy. The clinical scenario, in-utero imaging, and postmortem imaging will be discussed and compared with pathology. Finally, conclusions regarding the utility of postmortem MRI will be drawn.

Case report

A 33-year-old G1 P0 with history of multiple unsuccessful infertility treatments presented to William Beaumont Hospital at 13 weeks and 4 days gestation with heavy vaginal bleeding. She was examined in the emergency center, and pelvic ultrasonography revealed a single-live intrauterine pregnancy with subchorionic hemorrhage. At 19 weeks gestation, a routine anatomy scan revealed no fetal abnormalities. At 27 weeks gestation, she returned to the hospital after an ultrasound in her obstetrician’s office identified a fetal abdominal mass.

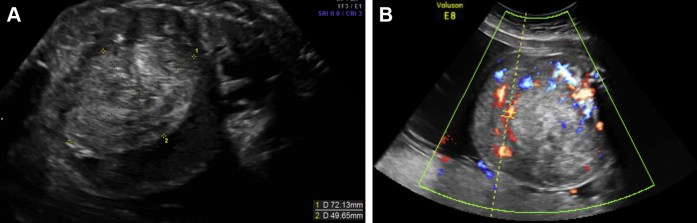

An obstetrical ultrasound demonstrated a live intrauterine pregnancy with a large mass compressing the liver and kidneys along with bilateral hydronephrosis and ascites. The origin of the mass was indeterminate sonographically; however, retroperitoneal origin was favored based on the relative displacement of the abdominal organs (Figs. 1A and B).

Fig. 1.

(A, B) Prenatal sagittal and axial sonographic images through the abdomen demonstrate a large abdominal mass anterior displacing the liver with significant internal vascularity.

At 28 weeks gestation, a fetal MRI was performed which also revealed an intra-abdominal mass, measuring 9.4 × 6.8 × 8.6 cm, likely arising from the retroperitoneum Fig. 2. The mass was displacing the liver and kidneys and demonstrated restricted diffusion. There was hepatic heterogeneity, likely representing metastatic disease or possibly multifocal hepatoblastoma. In addition, there was significant skin thickening and placentomegaly consistent with hydrops. At this time, a biophysical profile was performed which was scored as 2/8, and the patient was transferred to the high-risk obstetrical unit.

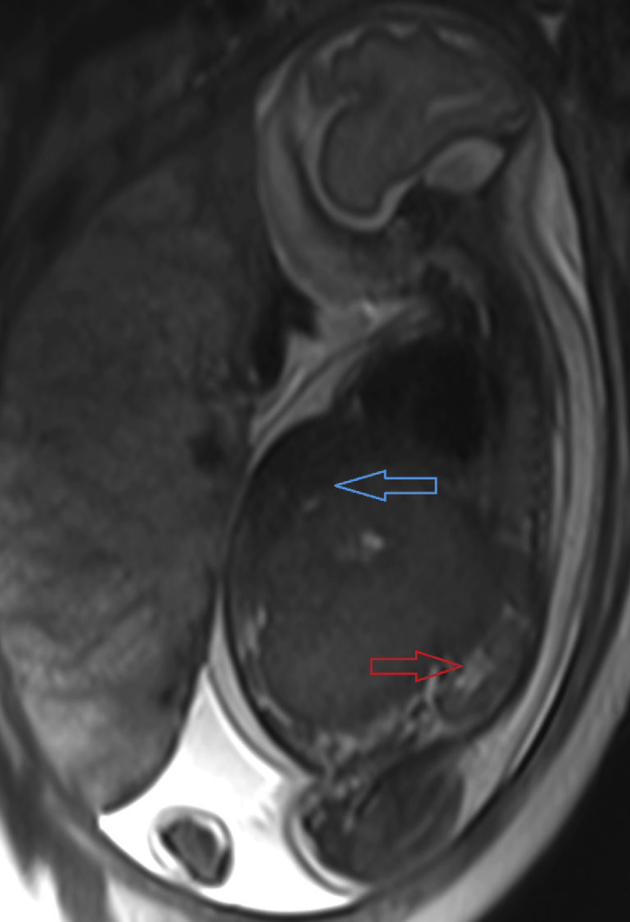

Fig. 2.

Prenatal MRI sagittal T2-weighted image through the fetus demonstrates large abdominal mass displacing liver (blue arrow) and kidney (red arrow).

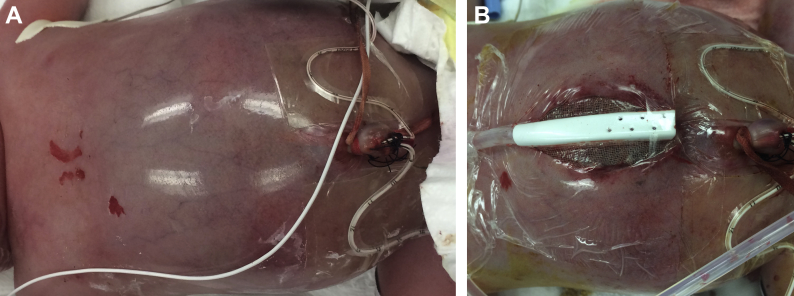

On August 25, 2015, nonreassuring fetal heart tones prompted delivery by low transverse cesarean section. Both the mother and baby survived delivery; however, the baby required intubation for oxygen desaturation. An emergent ultrasound performed at the bedside also failed to determine the origin of the tumor conclusively. There was sliding of the liver over the mass with respiratory movements, suggesting that the mass did not originate from the liver. An emergent bedside decompressive laparotomy was performed to treat the abdominal compartment syndrome. The laparotomy revealed a tumor arising in the right abdomen, extending well into the left abdomen. Liver metastases were noted. As the patient was profoundly coagulopathic, no biopsy or resection was possible, and a makeshift vacuum-assisted device was used to manage his open abdomen (Figs. 3A and B).

Fig. 3.

(A, B) Surgical images: Photographs of the protuberant abdomen before and after decompressive laparotomy.

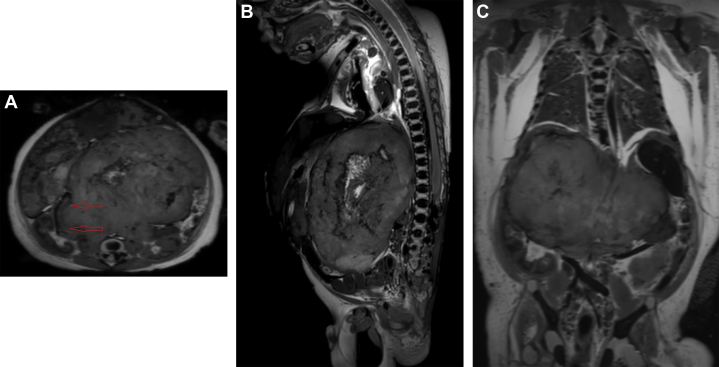

Renal failure and difficulty with ventilation led to irreversible acidosis. After a lengthy discussion, the family decided to withdraw support on August 26, 2015. On August 27, 2015, a postmortem full body MRI was performed along with limited tissue sampling. Three dimensional T1-weighted, T2-weighted, and T2*-weighted sequences were obtained on a Philips 3T scanner with voxel size of 0.6 × 0.6 × 0.6 mm (slice thickness), then reconstructed in the sagittal, coronal, and transverse planes.

A 9.3 × 6.2 × 6.7-cm heterogeneous mass was identified. It was predominantly hyperintense on T1 and hypointense on T2, with extensive blooming artifacts on T2*, consistent with internal calcifications. With the improved resolution of postmortem imaging, it was clear that the mass originated from the right adrenal gland and crossed the midline, displacing both kidneys and the liver. The left adrenal gland was normal. The liver contained multiple round lesions which had high T1 signal, low T2 signal, and blooming artifact on T2*, consistent with metastatic disease (Figs. 4A-C).

Fig. 4.

(A) Axial T2-weighted image shows the origin of the tumor demonstrated by a “claw sign” (red arrows) extending from the right adrenal gland, just anterior to the right kidney. (B) Sagittal T2-weighted image through the midline of the abdomen demonstrates a retroperitoneal origin of the mass with anterior/inferior displacement of the abdominal organs. (C) Coronal T2-weighted image demonstrates the extent of the mass extending into the left hemiabdomen.

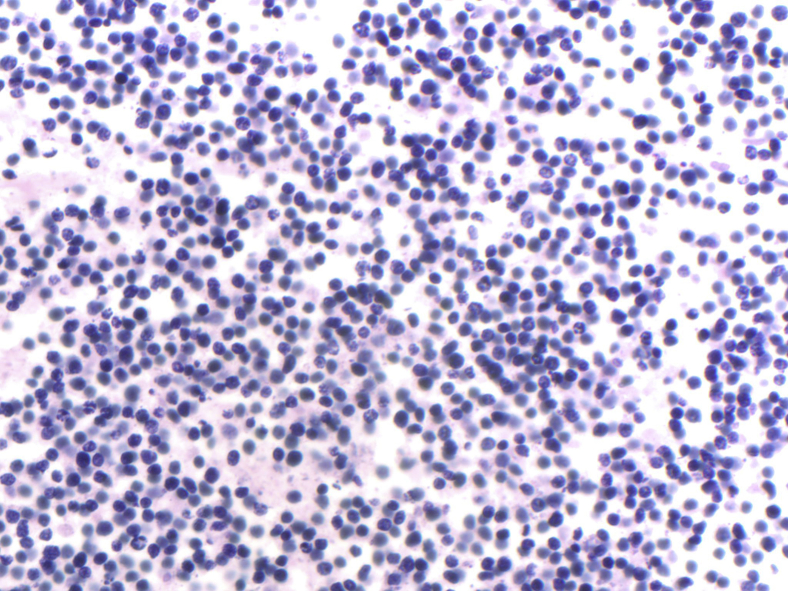

The parents consented to the procurement of neoplastic tissue for diagnostic purposes only. On gross pathologic evaluation, the abdomen was bulging, measuring 32 cm in circumference. The abdomen was opened, revealing a protruding liver with tan-white nodules and areas of necrosis and hemorrhage. A biopsy specimen was procured from the liver demonstrating a small round blue cell tumor with positivity for neuroendocrine markers (chromogranin and synaptophysin). Morphology was consistent with a stroma-poor, poorly differentiated neuroblastoma with favorable histology (Fig. 5). It was also noted that there were multiple cross sections of the placenta that demonstrated metastasizing small round blue tumor cells within the fetal vessels.

Fig. 5.

Stroma-poor, poorly differentiated neuroblastoma demonstrating a highly cellular lesion composed of small, round, primitive appearing cells with high nuclear: cytoplasmic ratio embedded in a background of neuropil.

Discussion

Neuroblastoma is the most common solid extracranial tumor of infants and children. Up to 50% of neuroblastomas are diagnosed before the age of 2 but can be diagnosed later in childhood as well. The earliest documentation of prenatal diagnosis of neuroblastoma was in 1983 by Fenart et al when a 1.4-cm hyperechoic adrenal mass was identified, and then removed following birth [1]. Since then, many case reports of fetal neuroblastoma have been published; however, relatively few demonstrate metastatic disease [2]. Improvements in prenatal imaging and widespread use of fetal ultrasonography have led to an increased rate of prenatal diagnosis of fetal neuroblastoma. The features of neuroblastoma on the antenatal ultrasound are variable and range from cystic, mixed solid and cystic, and completely solid with or without calcification. Patients with cystic neuroblastoma have a better outcome than those noncystic tumors [3]. Despite metastatic disease and large tumor burden, the prognosis is often considered favorable. Most notably, in patients with stage 4S neuroblastoma, which includes metastases to the liver, skin, or bone marrow, patients may have complete spontaneous regression of the tumor [4]. Ninety percent of fetal neuroblastomas arise in the adrenal glands, but can arise anywhere along the sympathetic chain. When a suprarenal mass is identified in utero, primary differential considerations often include neuroblastoma, hepatoblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, extralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration, and possibly adrenal hemorrhage. Ultrasound can often narrow the differential, and in cases where the diagnosis is not clear, fetal MRI can be of diagnostic aid [2], [5].

The typical gross pathologic, histologic, and MRI characteristics of neuroblastomas are discussed in the following paragraphs.

Gross pathology

Most neuroblastomas are smaller than 10 cm and may be infiltrative of surrounding tissue or circumscribed. Adrenal neuroblastomas are especially likely to appear circumscribed and may even appear to have a capsule; however, capsules are not commonly found in neuroblastomas. The mass is usually relatively soft. The tumor may have a lobulated appearance due to alternating stroma and hemorrhagic or cystic components. On cut sections, hemorrhage, cystic necrosis, and calcification can all be seen [6].

Histologic characteristics

Neuroblastomas are immature precursors of sympathetic cells. They contain a combination of neuroblasts and stroma. The neuroblasts appear small and round, containing little cytoplasm. Their nuclei are hyperchromatic and fill the majority of the cell, giving them their classic “small round blue cell” appearance. Background neuropil is typically present in differentiated tumors. Stroma-rich tumors also have a Schwann cell-rich stroma. A helpful diagnostic feature of neuroblastomas is the Homer–Wright Rosette, circular columns of tumor cells around a central core of neuropil. Necrosis, mitoses, hemorrhage, fibrosis, calcification, lymphocytic infiltrate, and karyorrhexis may be present as well. The presence or absence of Schwannian stroma, histologic evidence of differentiation, the mitotic-karyorrhectic index, along with the patient’s age, are all important factors in the final classification (favorable vs unfavorable histology) of these tumors.

MRI characteristics

The tumor is typically heterogeneous and will have a variable enhancement pattern. Signal intensity will typically be low on T1WI and high on T2WI. There is often little or no enhancement present. Cystic or necrotic components can easily be seen as high signal on T2WI. If there is hemorrhage, it will have high-signal intensity on T1WI. Calcifications may be more difficult to identify on MR but can be identified with T2*-weighted images. Because the tumors are composed of dense small round blue cells, they will restrict diffusion of water protons and appear bright on diffusion-weighted imaging. A claw sign may be seen, confirming the origin of the mass. If there is metastatic disease to the liver, MR is sensitive in detecting lesions as high-signal intensity on T2WI. Short-tau inversion recovery sequences can also aid in diagnosis of stage 4 or stage 4S disease [7]. Many of these findings which may be inconspicuous on fetal MRI are more apparent on postmortem MRI.

Postmortem MRI

Postmortem MRI offers an unparalleled ability to acquire highly detailed images of the entire body. The largest clinical trial comparing postmortem MRI to conventional autopsy was performed between March 1, 2007 and September 30, 2011 in London, United Kingdom, reviewing 400 cases of deceased fetuses and children up to 16 years of age. The results of their study indicated that minimally invasive autopsy (no incisions, only gross evaluation, and blood sampling) along with postmortem MRI has accuracy similar to that of traditional autopsy in detecting cause of death or gross pathologic abnormalities in fetuses, newborns, and infants [8].

Postmortem MRI eliminates many of the limitations of prenatal ultrasonography and fetal MRI. There is no artifact created from movement, and patient positioning can be fully controlled and manipulated as necessary. In contrast to fetal MRI, there is no limit to how long the subject can stay within the magnet, allowing for acquisition of 3-dimensional images with voxel size of 0.6 × 0.6 × 0.6 mm. Fetal MRI images are typically acquired in 2-dimensional with voxel size of 3.0 × 3.0 mm. The 3-dimensional acquisition with small voxel size increases the scan time from a few minutes to about 2 hours but improves signal to noise ratio, giving unparalleled resolution, and allowing differentiation of small anatomic details. To accommodate the increased scan time of these studies, they are often performed after hours on a dedicated research scanner. Finally, although 3T scans are considered safe at all gestational ages, many institutions prefer not to use 3T MRI scanners until 28 weeks gestation. All postmortem MRIs at our institution are performed on a Philips 3T MRI scanner.

Conclusions

Neuroblastoma is one of the most common tumors of infants and children and can usually be accurately diagnosed with MRI. Occasionally, neuroblastomas and other abnormalities are not clearly defined on prenatal imaging due to limitations, many of which do not interfere with postmortem MRI. Traditional autopsy remains the gold standard of postmortem diagnosis; however, postmortem MRI with limited pathologic sampling may offer accurate diagnostic information regarding cause of death and correlation with findings on prenatal imaging, especially in fetuses, newborns, and infants when traditional autopsy is not possible. Definitive classification of neonatal neoplasms can provide valuable information to families, as neonatal tumors may be part of a syndrome or disorder, many of which are genetic. This information can greatly impact the management of future pregnancies as there may be a role for prenatal and familial or genetic testing and counseling.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.Fenart D., Deville A., Donzeau M., Bruneton J.N. Retroperitoneal neuroblastoma diagnosed in utero. Apropos of 1 case. Journal de Radiologie. 1983;64(5):359–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flanagan S., Rubesova E., Jaramillo D., Barth R. Fetal suprarenal masses–assessing the complementary role of magnetic resonance and ultrasound for diagnosis. Pediatr Radiol. 2016;46(2):246–254. doi: 10.1007/s00247-015-3470-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Isaacs H. Fetal and neonatal neuroblastoma: retrospective review of 271 cases. Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2007;26(4):177–184. doi: 10.1080/15513810701696890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schleiermacher G., Rubie H., Hartmann O., Bergeron C., Chastagner P., Mechinaud F. Treatment of stage 4s neuroblastoma–report of 10 years’ experience of the French Society of Paediatric Oncology (SFOP) Br J Cancer. 2003;89:470–476. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oner E., Dinc S., Melek B. Prenatal diagnosis of adrenal neuroblastoma: a case report with a brief review of the literature. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/506490. Article ID 506490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lonergan G., Schwab C., Suarez E., Carlson C. Neuroblastoma, ganglioblastoma, and ganglioneuroma: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2002;22(4):911–934. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.22.4.g02jl15911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Papaioannou G., McHugh K. Neuroblastoma in childhood: review and radiological findings. Cancer Imaging. 2005;5(1):116–127. doi: 10.1102/1470-7330.2005.0104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thayyil S., Sebire N., Chitty L., Wade A., Chong W.K., Olsen O. Post-mortem MRI versus conventional autopsy in fetuses and children: a prospective validation study. Lancet. 2013;382(9888):223–233. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60134-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]