Abstract

A case of a right knee intra-articular osteolipoma in a 64-year-old man is reported. The patient presented for evaluation of a 1-year history of nontraumatic, mechanically-exacerbated, medial-sided right knee pain. Radiographs demonstrated a partially calcified 3.0 cm mass anterior to the distal medial femur at the suprapatellar fossa. Magnetic resonance imaging examination confirmed a 4.0 × 3.6 cm well-circumscribed mass deep to the medial patellofemoral ligament, with predominantly fat characteristics on T1-weighted and T2-weighted sequences. The mass had irregular ossification superiorly with surrounding heterogeneous enhancement. Histologic examination of an excisional biopsy showed the lesion to be an osteolipoma. Osteolipoma is a rare histologic variant of lipoma with osseous metaplasia, but should be considered in the differential of a fat-containing neoplasm with ossification.

Keywords: Osteolipoma, Ossifying lipoma, Knee joint

Case report

A 64-year-old Caucasian man was referred to our orthopedic outpatient center for a second opinion regarding a proximal right knee mass. The patient reported pain along the medial aspect of the knee for the past year, with recent notice of a palpable mass. The mechanical effects of the mass were increasingly interfering with his daily activities. The pain was described as a constant, moderate throbbing, exacerbated by activity. Conservative treatments, including physical therapy and various over-the-counter medications had failed to provide symptomatic relief.

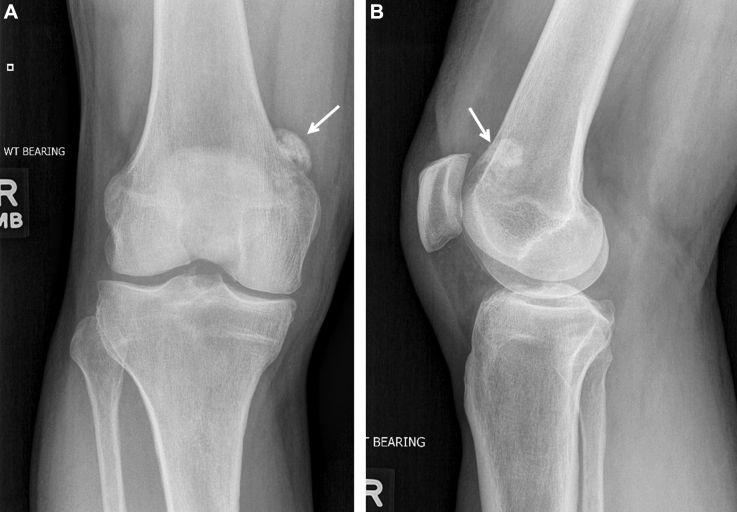

Initial outside hospital radiographs revealed a calcified mass anterior to the distal right medial femur in the region of the suprapatellar fossa (Fig. 1). Provided initial differential included parosteal osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and myositis ossificans, prompting an orthopedic oncology consult and subsequent referral to our outpatient orthopedic clinic.

Fig. 1.

(A) Frontal and (B) lateral knee radiographs demonstrate an area of ossification (arrows) anteromedial to the medial femoral condyle. No underlying osseous involvement is identified.

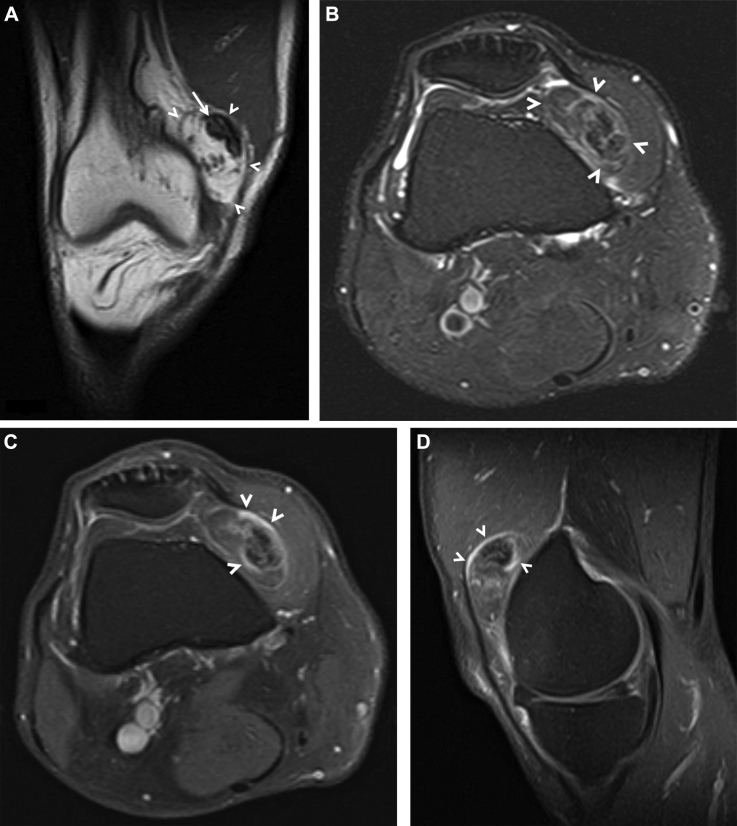

Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging was performed to further evaluate the mass, which demonstrated a 3.8 × 3.4 × 1.5 cm, well-circumscribed mass deep to the medial patellofemoral ligament, at the margin of the prefemoral fat pad (Fig. 2). The mass abutted the anteromedial femur and medial patellar facet without evidence of osseous involvement. The mass had predominantly fat-signal characteristics on both T1-weighted and T2-weighted fat suppression sequences. At the superior margin of the mass, there was an irregular region of T1-weighted and T2-weighted hypointense rim with central T1 hyperintensity that demonstrated signal suppression, consistent with ossification. Following gadolinium administration, the mass heterogeneously enhanced, greatest around the region of ossification. Based on imaging appearance, an intra-articular lipoma with dystrophic ossification was atop the differential diagnosis. The patient was offered conservative management with anti-inflammatory medications and observation vs surgical excision of the mass. He elected to proceed with surgical excision.

Fig. 2.

(A) Coronal T1-weighted and (B) axial T2-weighted fat-suppressed MR images demonstrate a well-circumscribed fat-containing mass (arrowheads) deep to the medial patellofemoral ligament. At the superior margin of the mass, there was an irregular region of T1-weighted and T2-weighted hypointense rim with central T1 hyperintensity (arrow) that demonstrated signal suppression, consistent with ossification. (C) Axial and (D) sagittal T1-weighted fat-suppressed postcontrast MR images show heterogeneously enhancement around the region of ossification (arrowheads). Incidentally, there is a “tear of the posterior horn” medial meniscus.

A limited median parapatellar arthrotomy was performed, extending from the inferior border of the patella proximally into the quadriceps tendon, sparing the quadriceps muscle fibers. The mass was encountered immediately beneath the tendon and found to be nonadherent to the surrounding tissues. Dissection was carried down circumferentially around the tumor, including a wide margin of surrounding tissue. Once it had been completely freed, the specimen was removed, tagged, and sent to pathology for permanent analysis. The arthrotomy and skin were closed in the standard fashion, and the patient tolerated the procedure well.

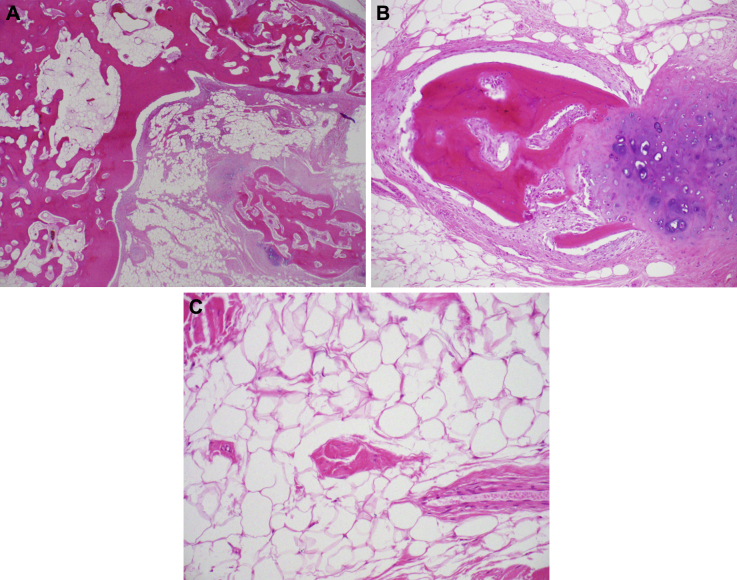

Gross examination of the resected specimen demonstrated an 8.1 × 3.7 × 1.1 cm mass. The mass was tan-brown, firm, ovoid, and surrounded by fibrofatty soft tissue. Histologic examination revealed mature adipose tissue in which a large fragment of cortical-type bone was embedded. In addition, isolated fragments of hyaline cartilage, some undergoing ossification were present (Fig. 3). The pattern was consistent with an osteolipoma.

Fig. 3.

Hematoxylin-eosin morphology of the osteolipoma. (A) Cortical-type bone with fatty marrow, associated with mature adipose tissue. A separate island of hyaline cartilage undergoing ossification is noted. Original magnification 20×. (B) Cartilage island undergoing ossification. Original magnification 40×. (C) Mature adipose tissue and scant fibrous tissue within the osteolipoma. Original magnification 200×.

Discussion

Lipomas are the most frequent soft tissue tumors and can include a variety of other mesenchymal elements. Based on the presence of variable amounts of other mesenchymal components that form an intrinsic part of the lipoma, the World Health Organization classification of human soft tissue and bone tumors describes 14 types of benign tumors comprising mature adipose tissue, including lipoma, myxolipoma, fibrolipoma, angiolipoma, and chondroid lipoma [1], [2]. Ossifying lipoma (osteolipoma) is the rarest subtype of lipoma, with the first case being reported in 1959 [3].

An osteolipoma is defined as a lesion with mature adipose tissue and randomly distributed trabeculae of laminated bone [4], [5], [6]. They have been found at various sites, with the highest frequency in the head and neck regions [7], [8], [9]. However, our review of the English-language literature using the keywords “osteolipoma” and “ossifying lipoma” revealed only 5 other reported cases of osteolipomas within the distal femur and/or knee region (Table 1). Two cases involved the distal femur [10], [11], 2 cases involved the infrapatellar tendon and Hoffa's fat pad, and 1 case involved the suprapatellar bursa [12].

Table 1.

Summary of osteolipomas about the knee, clinical, and radiologic data.

| Case | Reference | Age/sex | Location | Size, cm | X-ray | MR appearance | Symptoms/duration | Treatment/follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cheng et al | 21/M | Distal femur | 12 × 6 × 2 | NA | T1: well-demarcated, heterogeneous T2: lobular contour, heterogeneous signal intensity |

Activity-related pain/36 mo | Excision/no recurrence at 6 mo |

| 2 | Hashmi et al | 45/F | Distal femur | 8 × 6.5 × 14 | Ossification with fine trabeculation | T1/T2: lobulated and trabeculated areas | Painless mass/1.5 y | Biopsy/NA |

| 3 | Fritchie et al | 51/M | Lateral anterior Infra-patellar knee |

4.2 × 4 × 2.8 | Mass with calcific stippling | T1: heterogeneous low T2: heterogeneous low and high C: intense heterogeneous enhancement |

Painless mass/3 mo | Excision/no recurrence at 8 mo |

| 4 | Fritchie et al | 31/F | Infrapatellar tendon | 5.2 × 4.3 × 4.1 | Retropatellar mass | T1: heterogeneously isointense and hypointense to fat. C: brisk enhancement in nonfatty components |

Nontender, irritating mass/1 y | Excision/no recurrence at 25 mo |

| 5 | Pudlowski et al | 53/M | Suprapatellar bursa | 5.5 × 4.5 × 2.5 | Ossified mass | NA | Pain, swelling, instability/5 mo | Medial meniscectomy/NA |

| 6 | 64/M | Anterior knee joint | 8.1 × 3.7 × 1.1 | Ossified mass | T1: well-circumscribed, heterogeneously lobular C: intense heterogeneous enhancement throughout |

Knee pain, exacerbated by activity/12 mo | Excision/NA |

M, male; F, female; NA, not available; C, contrast-enhanced.

Including our patient, the age of these 6 patients ranged from 21 to 64 years (mean of 41.2 years), involving 4 men and 2 women. Symptoms were described in all 6 cases, with 4 reporting joint pain ranging from 3-36 months in duration, exacerbated by activity, and causing difficulty while performing simple tasks such as walking [11]. Two of the 4 patients reported joint pain at rest [12]. Both patients presented by Fritchie et al [13] reported painless masses with normal range of motion. All 6 patients elected to have the tumor excised, with 3 patients reported to be alive and well at 6-25 months following the procedure [10], [13].

MR Imaging characteristics were described in 5 of the 6 cases. All reports describe the mass as heterogeneous on T1 and/or T2 sequences, with areas of macroscopic fat signal and ossification. Including our patient, gadolinium contrast was administered in 3 cases, all of which demonstrated heterogeneous enhancement [13]. Two of the cases showed evidence of underlying osseous involvement [10], [11].

The radiographic differential diagnosis for an ossified mass is dependent on many factors, including location. When intra-articular or juxta-articular in location, mechanical symptoms may lead to earlier presentation, and therefore, smaller mass sizes which may result in difficulty differentiating ossification from calcification. The end result is a broad radiographic differential diagnosis of a calcified and/or ossified intra-articular mass including benign entities, such as a hemangioma, synovial chondromatosis, calcified synovitis, myositis ossificans, or a loose body. However, malignancies such as conventional or surface-based osteosarcoma, or soft tissue sarcomas such as a synovial sarcoma, may also enter the differential [14]. This emphasizes the importance of MR evaluation of juxta and/or intra-articular masses to evaluate for characteristics that can narrow the differential diagnosis, as well as aid in presurgical planning or staging.

Demonstration of a fat-containing mass on MR directs the differential to lipomatous tumors, primarily lipoma and liposarcoma. In the extremities, well-defined lesions composed of pure fat or containing thin septa (<2 mm) on MR are considered lipomas, especially in the absence of contrast enhancement [15]. However, the mature fat of a lipoma is subject to the same secondary inflammatory processes of fat anywhere in the body and can be complicated by osseous metaplasia, fat necrosis, calcification, fibrosis, and myxoid change, leading to prominent nonadipose areas mimicking the findings commonly associated with liposarcoma. Imaging features that suggest malignancy include the presence of thickened septa (>2 mm), large size, deep (subfascial) location, presence of nodular nonadipose areas, contrast enhancement, and decreased percentage of fat composition [16]. In addition to the well-differentiated subtype, the World Health Organization Classification of Soft Tissue Tumors identifies 3 other subtypes of liposarcoma: myxoid and/or round cell, pleomorphic, and dedifferentiated [1]. On CT and MR images, the appearance of liposarcoma reflects the degree of tumor differentiation: the more differentiated the tumor, the more closely it resembles adipose tissue [17]. Thus, a well-differentiated liposarcoma will typically appear as a predominantly fatty mass having irregularly thickened, linear, swirled, and/or nodular septa. In general, the other 3 histologic subtypes of liposarcomas contain significantly less fat radiologically (<25%). Notably, the dedifferentiated subtype has characteristics of a well-differentiated liposarcoma with an associated nonlipomatous component, which might show signs of hemorrhage and/or necrosis [18].

In our case, the mass was well circumscribed, predominantly fat-containing with no thickened septa, and with a focus of ossification, favoring an osteolipoma. However, the deep location and heterogeneous enhancement were findings that prevented excluding well-differentiated liposarcoma from the differential. This is in keeping with prior studies demonstrating the difficulty distinguishing osteolipomas from well-differentiated liposarcomas secondary to the heterogeneous appearance of osteolipomas on imaging studies and nonspecific presentation [17]. In this setting, we felt a wide local excision, preoperatively planned as if managing a sarcoma was the most appropriate treatment.

In conclusion, osteolipomas are a rare occurrence. When arising in a juxta and/or intra-articular location, they result in a broad differential diagnosis that should be further evaluated with MR. Because of the absence of specific radiologic findings, the differential diagnosis for lesions with fatty and osseous components should include not only malignant entities such as liposarcoma but also heterologous differentiation of rather benign lipomas such as an osteolipoma, especially in the setting of internal mature bony formation. In our view, multidisciplinary communication between the radiologist and treating surgeon is essential to correlate symptomatology and any prior treatment response that may raise a suspicion for malignancy. Although extremely rare, definitive evaluation and treatment of osteolipomas may require wide local excision, and ideally should be undertaken by an orthopedic oncologist given the potential for a sarcoma diagnosis.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.Fletcher C.D. The evolving classification of soft tissue tumours - an update based on the new 2013 WHO classification. Histopathology. 2014;64(1):2–11. doi: 10.1111/his.12267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fletcher C.D.M., World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer . 4th ed. IARC Press; Lyon: 2013. WHO classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plaut G.S., Salm R., Truscott D.E. Three cases of ossifying lipoma. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1959;78:292–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saghafi S., Mellati E., Sohrabi M., Raahpeyma A., Salehinejad J., Zare-Mahmoodabadi R. Osteolipoma of the oral and pharyngeal region: report of a case and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;105(6):e30–e34. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Obermann E.C., Bele S., Brawanski A., Knuechel R., Hofstaedter F. Ossifying lipoma. Virchows Arch. 1999;434(2):181–183. doi: 10.1007/s004280050324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adebiyi K.E., Ugboko V.I., Maaji S.M., Ndubuizu G. Osteolipoma of the palate: report of a case and review of the literature. Niger J Clin Pract. 2011;14(2):242–244. doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.84029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Durmaz A., Tosun F., Kurt B., Gerek M., Birkent H. Osteolipoma of the nasopharynx. J Craniofac Surg. 2007;18(5):1176–1179. doi: 10.1097/scs.0b013e31814b2b61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kameyama K., Akasaka Y., Miyazaki H., Hata J. Ossifying lipoma independent of bone tissue. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2000;62(3):170–172. doi: 10.1159/000027741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amaral M.B., Borges C.F., de Freitas J.B., Capistrano H.M., Mesquita R.A. Osteolipoma of the oral cavity: a case report. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2015;14(Suppl. 1):195–199. doi: 10.1007/s12663-012-0413-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng S., Lu S.C., Zhang B., Xue Z., Wang H.W. Rare massive osteolipoma in the upper part of the knee in a young adult. Orthopedics. 2012;35(9):e1434–e1437. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20120822-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hashmi A.A., Malik B., Edhi M.M., Faridi N., Ashraful M. A large parosteal ossifying lipoma of lower limb encircling the femur. Int Arch Med. 2014;7(1):5. doi: 10.1186/1755-7682-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pudlowski R.M., Gilula L.A., Kyriakos M. Intraarticular lipoma with osseous metaplasia: radiographic-pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1979;132(3):471–473. doi: 10.2214/ajr.132.3.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fritchie K.J., Renner J.B., Rao K.W., Esther R.J. Osteolipoma: radiological, pathological, and cytogenetic analysis of three cases. Skeletal Radiol. 2012;41(2):237–244. doi: 10.1007/s00256-011-1241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedman M.V., Kyriakos M., Matava M.J., McDonald D.J., Jennings J.W., Wessell D.E. Intra-articular synovial sarcoma. Skeletal Radiol. 2013;42(6):859–867. doi: 10.1007/s00256-013-1589-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murphey M.D., Arcara L.K., Fanburg-Smith J. From the archives of the AFIP: imaging of musculoskeletal liposarcoma with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2005;25(5):1371–1395. doi: 10.1148/rg.255055106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kransdorf M.J., Bancroft L.W., Peterson J.J., Murphey M.D., Foster W.C., Temple H.T. Imaging of fatty tumors: distinction of lipoma and well-differentiated liposarcoma. Radiology. 2002;224(1):99–104. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2241011113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peterson J.J., Kransdorf M.J., Bancroft L.W., O'Connor M.I. Malignant fatty tumors: classification, clinical course, imaging appearance and treatment. Skeletal Radiol. 2003;32(9):493–503. doi: 10.1007/s00256-003-0647-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kransdorf M.J., Meis J.M., Jelinek J.S. Dedifferentiated liposarcoma of the extremities: imaging findings in four patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;161(1):127–130. doi: 10.2214/ajr.161.1.8517290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]