Abstract

Endothermy is an evolutionary innovation in eutherian mammals and birds. In eutherian mammals, UCP1 is a key protein in adaptive nonshivering thermogenesis (NST). Although ucp1 arose early in the vertebrate lineage, the loss of ucp1 was previously documented in several reptile species (including birds). Here we determine that ucp1 was lost at the base of the reptile lineage, as we fail to find ucp1 in every major reptile lineage. Furthermore, though UCP1 plays a key role in mammalian NST, we confirm that pig has lost several exons from ucp1 and conclude that pig is not a sole outlier as the only eutherian mammal lineage to do so. Through similarity searches and synteny analysis, we show that ucp1 has also been lost/pseudogenized in Delphinidae (dolphin, orca) and potentially Xenarthra (sloth, armadillo) and Afrotheria (hyrax). These lineages provide models for investigating alternate mechanisms of thermoregulation and energy metabolism in the absence of functional UCP1. Further, the repeated losses of a functional UCP1 suggest the pervasiveness of NST via UCP1 across the mammalian lineage needs re-evaluation.

Keywords: UCP1, thermogenesis, cetacean, lizard, snake, turtle

1. Background

Endothermy, the ability to produce endogenous heat, is an evolutionary innovation. In brown/beige adipose tissue of eutherian mammals, UCP1 serves as a proton leak across the inner mitochondrial membrane allowing energy to dissipate as heat. UCP1 is extensively studied for its role in adaptive nonshivering thermogenesis (NST), energy expenditure and metabolic disease. Birds have lost ucp1 [1], though ucp1 and paralogues ucp2 and ucp3 are present in fishes and amphibians [2]. Absence of ucp1 in lizards [3] suggests the potential for ucp1 to have been lost in the lineage leading to all reptiles, but lack of extensive genomic data has prevented a thorough evaluation until now.

Within mammals, the Suidae (pig, European wild boar and African wart-hog) were identified as the only known eutherian mammals to have lost a functional ucp1 [4,5]. This loss of ucp1 may have occurred when the ancestral suid was living in tropical and subtropical environments and, thus, could survive without NST via UCP1 [4]. While current-day domestic and wild pigs struggle with thermoregulation, they are able to maintain body temperature by shivering thermogenesis and nesting and cuddling behaviours [4]. Thus, we pose the question—if pigs can manage without ucp1, has ucp1 been lost repeatedly in eutherian mammals?

2. Material and methods

We extensively tested for the presence of ucp1 across the amniote phylogeny—details in electronic supplementary material, S1 (text and figures) and S2 (tables). To conclude that ucp1 was missing from the genomes of particular groups, we examined genomic/transcriptomic data from 127 species: 15 squamates, 52 birds, four crocodilians, seven turtles, one monotreme, three marsupials and 45 eutherian mammals (electronic supplementary material, table S1). We first assayed whether ucp1 was annotated on Ensembl, and whether ucp1 was detected in transcriptome alignments from 66 amniotes from our previous work [6,7]. If these provided no evidence of ucp1 in a particular species, we assayed for ucp1 in its syntenic location [2].

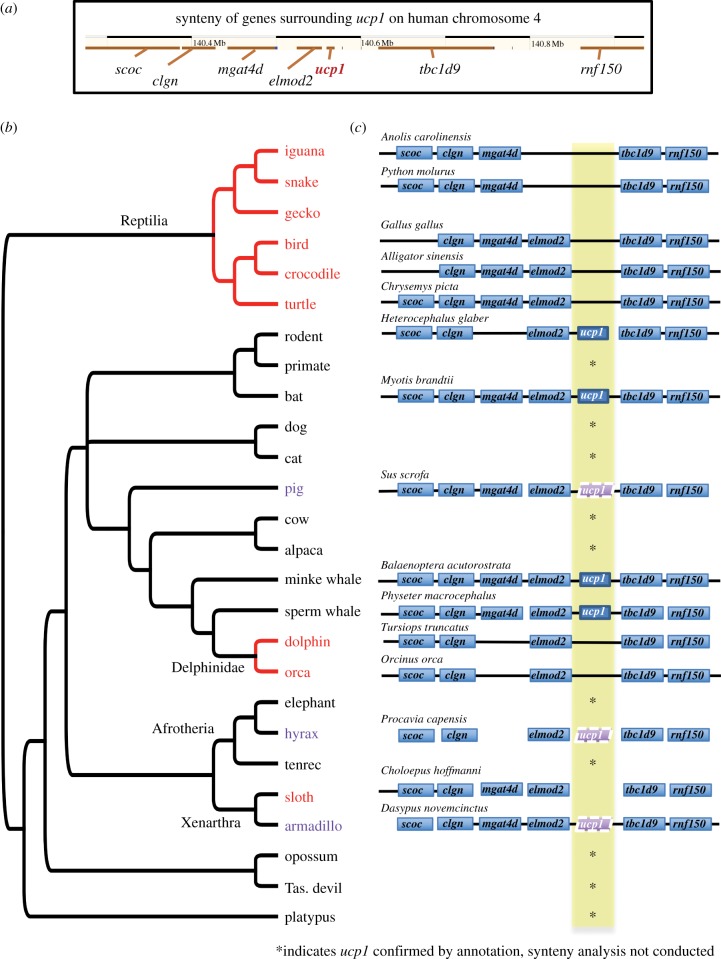

The syntenic position of ucp1 is highly conserved between frog and mammals (electronic supplementary material, figure S1), occurring between scoc, clgn, mgat4d and elmod2 on the one side and tbc1d9 and rnf150 on the other (figure 1a). This conservation of synteny provides a powerful assay to determine if ucp1 is likely absent in specific taxa or if any remnants of ucp1 exist [2]. Thereby, we made a BLASTn query of exon sequences from ucp1 and the six genes flanking ucp1 (electronic supplementary material, S3 [9] and table S2). Using BLASTn (e-value = 10) we queried genomes (or transcriptomes, if a genome was unavailable) for avian (n = 52) and non-avian (n = 27) reptiles and 11 mammals lacking evidence for ucp1 in Ensembl (table 1).

Figure 1.

(a) Chromosomal location of human ucp1 in Ensembl [8]. (b) Phylogeny illustrating the lineages with ucp1 losses (red) or pseudogenes (purple). Pseudogenes were classified if ucp1 remnants were present in the synteny and genome assembly analysis, but likely not functional owing to substantial deletions or premature termination codons. (c) Synteny analyses results for representative species represented by cartoons of the scaffold(s) upon which ucp1 and flanking genes were found (details in electronic supplementary material, tables S3 and S4). A solid line connecting genes indicates evidence of flanking genes being found on the same scaffold; we did not assess whether flanking genes were functional. Asterisk indicates ucp1 was confirmed by annotation, and synteny analysis was not conducted.

Table 1.

Summary of evidence for an intact, functional UCP1 in key species (details in electronic supplementary material, table S1).

| common name | species name | in Ensembl (electronic supplementary material, table S1) | in transcriptomes from McGaugh et al. 2015 [6,7] (electronic supplementary material, table S5) | detected in synteny analyses using BLASTn (electronic supplementary material, tables S2–S4)a | evidence of functional UCP1 by tBLASTn to genome (electronic supplementary material, table S6)b | evidence of ucp1 by BLASTn to raw sequence data (electronic supplementary material, tables S7–S30)c | conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| reptiles, squamates | |||||||

| anole lizard | Anolis carolinensis | no | no | no | no | no | ucp1 lost |

| python | Python molurus bivittatus | n.a. | n.a. | no | no | no | ucp1 lost |

| king cobra | Ophiophagus hannah | n.a. | n.a. | no | no | no | ucp1 lost |

| reptiles, birds | |||||||

| mousebird | Colius striatus | n.a. | n.a. | no | no | no | ucp1 lost |

| ostrich | Struthio camelus australis | n.a. | n.a. | no | no | no | ucp1 Lost |

| peregrine falcon | Falco peregrinus | n.a. | no | no | no | no | ucp1 lost |

| saker falcon | Falco cherrug | n.a. | no | no | no | no | ucp1 lost |

| white-throated tinamou | Tinamus guttatus | n.a. | n.a. | no | no | no | ucp1 lost |

| zebra finch | Taeniopygia guttata | no | no | no | no | no | ucp1 lost |

| reptiles, crocodilians | |||||||

| Chinese alligator | Alligator sinensis | n.a. | no | no | no | no | ucp1 lost |

| American alligator | Alligator mississippiensis | n.a. | no | no | no | no | ucp1 lost |

| saltwater crocodile | Crocodylus porosus | n.a. | n.a. | no | no | no | ucp1 lost |

| gharial | Gavialis gangeticus | n.a. | n.a. | n.a.d | no | no | ucp1 lost |

| reptiles, turtle | |||||||

| green sea turtle | Chelonia mydas | n.a. | n.a. | no | no | no | ucp1 lost |

| painted turtle | Chrysemys picta | n.a. | no | no | no | no | ucp1 lost |

| Chinese softshell turtle | Pelodiscus sinensis | no | no | no | no | no | ucp1 lost |

| mammals | |||||||

| Brandt's bat | Myotis brandtii | n.a. | yes | yes | yes | yes | ucp1 present |

| hyrax | Procavia capensis | no | n.a. | yesd | no, remnants | no | ucp1 likely pseudogenized |

| naked mole rat | Heterocephalus glaber | n.a. | yes | yes | yes | yes | ucp1 present |

| pig | Sus scrofa | no | no | yes | no, remnants | yes | ucp1 pseudogenized |

| vole | Microtus ochrogaster | n.a. | yes | yes | yes | n.a. | ucp1 present |

| mammals, Delphinidae | |||||||

| dolphin | Tursiops truncatus | no | no | no | no | no | ucp1 lost |

| orca | Orcinus orca | n.a. | n.a. | no | no | no | ucp1 lost |

| minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | n.a. | n.a. | yes | yes | yes | ucp1 present |

| sperm whale | Physeter macrocephalus | n.a. | n.a. | yes | yes | yes | ucp1 present |

| mammals, Xenarthra | |||||||

| armadillo | Dasypus novemcinctus | no | no | yes | no, remnants | no | ucp1 pseudogenized |

| sloth | Choloepus hoffmanni | no | n.a. | nod | no | no | ucp1 likely lost |

aQuery contained exons to flanking genes and ucp1, e-value = 10. Detects intact and remnants of ucp1.

bConvincing evidence of an intact, functional UCP1 includes hits to multiple exons with more than 75% identity that are not hits to paralogues or other genes in the larger protein family.

cConvincing evidence of an intact, functional ucp1 includes more than 75% of the query length covered with e-value = 0.01, and BLAST hits are not to paralogues ucp2 or ucp3.

dFragmented assembly; flanking genes were found on different scaffolds.

We used UCP1 protein sequences (electronic supplementary material, S4 [9] and table S2) to query the genomes (e-value = 0.01) with tBLASTn. Lastly, we used BLASTn to query the raw read files (e-value = 0.01) used for genome assembly from avian and non-avian reptiles (four crocodilians, two snakes, three turtles, six birds) for evidence of ucp1 using human, platypus and frog ucp1 sequences (electronic supplementary material, S5 [9]). For birds, we queried basal lineages (ostrich and tinamou) [10], a well-sequenced species (zebra finch), and those that had weak BLASTn hits from the synteny analysis (mousebird, saker falcon, peregrine falcon). Likewise, we used human, cow, elephant and mouse ucp1 sequences (electronic supplementary material, S6 [9] and table S7) to assay the raw reads from 10 of the 11 mammals above (vole was excluded because ucp1 and all flanking genes were located on the same scaffold). We set an e-value of 0.01 and required 75% of the length or greater of a ucp1 query sequence to be matched to conclude there was strong evidence of ucp1 in raw genomic read files.

3. Results and discussion

(a). ucp1 lost at base of reptile lineage

We found no evidence of a full-length, intact ucp1 in reptiles in Ensembl, the alignments from [6,7], queries for ucp1 in the syntenic location, tBLASTn queries or BLASTn queries to raw genomic reads (table 1; electronic supplementary material, tables S1, S3–S20). We checked for BLAST hits to flanking genes scoc, clgn, mgat4d, elmod2, tbc1d9 and rnf150 (figure 1; electronic supplementary material, table S2). For all squamates, all turtles and Chinese alligator, we found evidence for four to six flanking genes in syntenic order, but no matches of ucp1 in BLASTn queries (figure 1c; electronic supplementary material, tables S2 and S3). For crocodile, American alligator and gharial, we found small BLASTn hits (59–113 nt) with 80–88% identity to a frog ucp1 exon, but these hits localized to the scaffold containing ucp2/ucp3 (electronic supplementary material, table S3). For some of the crocodilian genomes, the flanking genes were localized to two or more scaffolds rendering synteny difficult to assess. The few tBLASTn hits for various reptiles were to paralogues and had low per cent identity to UCP1 (electronic supplementary material, S1 and tables S1 and S6). For BLASTn searches to raw reads in turtles, green sea turtle and painted turtle exhibited coverage of raw reads across 71–73% of the length of at least one of the ucp1 query sequences (electronic supplementary material, tables S1, S12–S13), but these are likely raw reads from paralogues given that matches to paralogues using tBLASTn were found for these species. For all other non-avian reptiles, we found no strong evidence for ucp1 in the raw genomic reads.

Among the 52 bird genomes, we found evidence for conserved synteny of the region surrounding ucp1, but no evidence that an intact, full-length ucp1 was present (table 1). For five bird species, there were small regions (27–68 nt) with high similarity to ucp1 (88–100%) but these were not in the proper syntenic location (electronic supplementary material, table S4; in two cases with annotation available these hits matched the location for ucp3); likewise, we found little evidence of ucp1 in the raw genomic reads (electronic supplementary material, tables S15–S20).

Therefore, our analysis demonstrates that intact, full-length ucp1 is not present in genomes from the major reptile clades, indicating ucp1 was lost early in the lineage leading to present-day reptiles.

(b). Loss of functional UCP1 in multiple mammalian lineages

We confirm there is no evidence for an intact, full-length ucp1 in pig [4,5] (table 1; electronic supplementary material, tables S1, S3 and S28), and we found no evidence for intact, full-length ucp1 in cetaceans from the clade Delphinidae (dolphin, orca), in species from Xenarthra (sloth, armadillo) and in hyrax (figure 1b and table 1; electronic supplementary material, tables S1, S3, S6, S21, S23–S26 and S29).

The dolphin genome assembly contained hits to four flanking genes that span the syntenic location for ucp1 (electronic supplementary material, tables S1 and S3; figure 1c). Yet, we did not recover any hits to ucp1 in the dolphin genome assembly, and ucp1 is not annotated in dolphin on Ensembl. Orca contained contiguous hits on the same scaffold for five flanking genes, but no ucp1 sequence (orca is not on Ensembl) (electronic supplementary material, table S1). For either species, the only hits with more than 50 PID (per cent identity, electronic supplementary material, table S6) were to ucp2 and ucp3 when using tBLASTn to query the genome assemblies using the UCP1 protein sequence, and no strong hits to ucp1 were found in the raw genomic reads (electronic supplementary material, tables S23 and S26). Although the presence of UCP1 has been proposed in dolphins based on immunological detection [11], the evidence is weak and may be due to unspecific binding of the antibodies, as has occurred in mice [12] and pigs [5].

Our results indicate a likely loss of ucp1 in Delphinidae (figure 1 and table 1), but not all cetaceans, as both minke whale (Balaenopteridae) and sperm whale (Physeteridae) contained ucp1 in the syntenic location (table 1; electronic supplementary material, tables S1 and S3), tBLASTn matches to cow UCP1 in the genome assembly (electronic supplementary material, table S6), and coverage of raw genomic reads across most of the ucp1 sequence length (electronic supplementary material, tables S25 and S30). Minke and sperm whale, therefore, also serve as a positive control that our methods would detect ucp1 if it were present in dolphin and orca. Additional members of the Delphinidae clade are strong candidates for future work on ucp1 loss in mammals.

Our analyses suggest that ucp1 is likely pseudogenized in armadillo and hyrax and lost in sloth (figure 1c and table 1). For armadillo, we found a BLASTn nucleotide hit for elephant ucp1 exon 7 (same as exon 6 in human) on the same scaffold as all six of the flanking genes. On this syntenic scaffold, tBLASTn searches confirmed the match to exon 6/7. tBLASTn also found matches to 34 amino acids of exon 2 and several amino acids at the 3′ end of exon 5 of ucp1 on the syntenic scaffold. BLASTp confirmed that UCP1 was the best hit in the NCBI non-redundant database. Alignment of the hits to the query protein sequences identified premature stop codons (electronic supplementary material, figure S2), providing further support for ucp1 likely being pseudogenized. Curiously, on a different scaffold we found BLASTn and tBLASTn hits to exon 6 of ucp1. This different scaffold did not contain paralogues ucp2 or ucp3. No additional parts of ucp1 were found to have hits with more than 0.5 PID within the armadillo genome assembly. ucp1 is not annotated by Ensembl in armadillo, and raw armadillo genomic reads covered less than 63% of the length of cow and human ucp1 (electronic supplementary material, tables S1 and S21). In line with a pseudogenized UCP1, the armadillo has relatively low body temperature and is heavily reliant upon shivering thermogenesis and heat-conserving behaviour in response to cold [13].

Sloth and hyrax lack evidence for a full-length, intact ucp1. No annotated ucp1 is present in Ensembl. Five (sloth) and six (hyrax) syntenic flanking genes had BLASTn hits, but not ucp1 (electronic supplementary material, table S3). The syntenic block was split across multiple scaffolds in both species, limiting our synteny analyses. In hyrax, matches to the UCP1 protein were found via tBLASTn for exon 5 and exon 6 (75–76% identity; electronic supplementary material, table S6). Although these were not located on the scaffolds containing flanking genes, a BLASTp of this hit to NCBI confirms it is UCP1. Alignment to the protein query sequences indicates premature termination codons may exist in these remnants, further supporting ucp1 pseudogenization in hyrax (electronic supplementary material, figure S2). For sloth, most tBLASTn hits were to scaffolds containing paralogues, ucp2 and ucp3 (electronic supplementary material, tables S1 and S6). We detected a match to exon 6 (70% identity, 22 amino acids) but a BLASTp of this hit to NCBI identified this as kidney mitochondrial carrier protein 1. We did not detect substantial matches in the raw sequence data (electronic supplementary material, tables S24 and S29) for either hyrax (100× raw genome coverage) or sloth (56× raw genome coverage). This combination of evidence suggests a loss of functional UCP1 in sloth and hyrax, but these results are interpreted cautiously given the fragmented nature of the genome assemblies. Interestingly, while hyrax can maintain a relatively high body temperature with a drop in ambient temperature [14], sloths have pronounced heterothermy as their body temperature drops in parallel with ambient temperature from 34 to 20°C [15]. Further research in these groups would be insightful into the energetic consequences of UCP1 loss and alternative mechanisms of thermoregulation.

4. Conclusion

As ucp1 is present in fish and amphibians, our analysis provides definitive evidence that ucp1 was lost at the base of the reptile lineage. Within mammals, we find that multiple lineage-specific losses of functional UCP1 have occurred, including suids (pigs), Delphinidae (dolphin, orca), and potentially hyrax and Xenarthra (sloth, armadillo). These lineages may provide new models for investigating alternate mechanisms of thermoregulation and energy metabolism in the absence of functional UCP1. Further, these losses illuminate the need for a deeper evaluation of UCP1 function across the mammalian tree and the development of additional hypotheses as to what environmental and/or physiological factors are permissive to the loss of UCP1.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Sonia Ehrlich helped early in this project. Two anonymous reviewers provided insightful comments for improvement.

Data accessibility

All genomic/transcriptomic data are available in Ensembl, NCBI or Dryad (see links in electronic supplementary material, S2, tables S1 and S2). Supporting materials are provided as the electronic supplementary material and in the Dryad Digital Repository: http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.934fg [9].

Authors' contributions

S.M. analysed the data. T.S.S. drafted the manuscript. Both authors contributed to the concept of the study, interpretation of the data, and revising the manuscript, approved the final version and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Funding

We acknowledge Minnesota Super Computing Institute, University of Minnesota and Auburn University for financial support to the authors.

References

- 1.Emre Y, Hurtaud C, Ricquier D, Bouillaud F, Hughes J, Criscuolo F. 2007. Avian UCP: the killjoy in the evolution of the mitochondrial uncoupling proteins. J. Mol. Evol. 65, 392–402. ( 10.1007/s00239-007-9020-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jastroch M. 2005. Uncoupling protein 1 in fish uncovers an ancient evolutionary history of mammalian nonshivering thermogenesis. Physiol. Genomics 22, 150–156. ( 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00070.2005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mezentseva NV, Kumaratilake JS, Newman SA. 2008. The brown adipocyte differentiation pathway in birds: an evolutionary road not taken. BMC Biol. 6, 17 ( 10.1186/1741-7007-6-17) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berg F, Gustafson U, Andersson L. 2006. The uncoupling protein 1 gene (UCP1) is disrupted in the pig lineage: a genetic explanation for poor thermoregulation in piglets. PLoS Genet. 2, e129 ( 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020129) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jastroch M, Andersson L. 2015. When pigs fly, UCP1 makes heat. Mol. Metab. 4, 359–362. ( 10.1016/j.molmet.2015.02.005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGaugh SE, Bronikowski AM, Kuo C-H, Reding DM, Addis EA, Flagel LE, Janzen FJ, Schwartz TS. 2015. Rapid molecular evolution across amniotes of the IIS/TOR network. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 7055–7060. ( 10.1073/pnas.1419659112) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGaugh SE, Bronikowski AM, Kuo C-H, Reding DM, Addis EA, Flagel LE, Janzen FJ, Schwartz TS.2015. Data from: Rapid molecular evolution across amniotes of the IIS/TOR network. Dryad Digital Repository. ( ) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Yates A, et al. 2015. Ensembl 2016. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D710–D716. ( 10.1093/nar/gkv1157) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGaugh S, Schwartz TS.2016. Data from: Here and there, but not everywhere: the repeated loss of uncoupling protein 1 in amniotes. Dryad Digital Repository. ( ) [DOI]

- 10.Prum RO, Berv JS, Dornburg A, Field DJ, Townsend JP, Lemmon EM, Lemmon AR. 2015. A comprehensive phylogeny of birds (Aves) using targeted next-generation DNA sequencing. Nature 526, 569–573. ( 10.1038/nature15697) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hashimoto O, et al. 2015. Brown adipose tissue in cetacean blubber. PLoS ONE 10, e0116734 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0116734) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rousset S, Alves-Guerra MC, Ouadghiri-Bencherif S, Kozak LP, Miroux B, Richard D, Bouillaud F, Ricquier D, Cassard-Doulcier AM. 2003. Uncoupling protein 2, but not uncoupling protein 1, is expressed in the female mouse reproductive tract. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 45 843–45 847. ( 10.1074/jbc.M306980200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johansen K. 1961. Temperature regulation in the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus mexicanus). Physiol. Zool. 34, 126–144. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown KJ, Downs CT. 2006. Seasonal patterns in body temperature of free-living rock hyrax (Procavia capensis). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 143, 42–49. ( 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.10.020) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Irving L, Scholander PF, Grinnell SW. 1994. Experimental studies of the respiration of sloths. J. Cell. Physiol. 20, 189–210. ( 10.1002/jcp.1030200207) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All genomic/transcriptomic data are available in Ensembl, NCBI or Dryad (see links in electronic supplementary material, S2, tables S1 and S2). Supporting materials are provided as the electronic supplementary material and in the Dryad Digital Repository: http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.934fg [9].