Abstract

Effective recovery of activated brain infiltrating lymphocytes is critical for investigations involving murine neurological disease models. To optimize lymphocyte recovery, we compared two isolation methods using brains harvested from seven-day Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) and TMEV-OVA infected mice. Brains were processed using either a manual dounce based approach or enzymatic digestion using type IV collagenase. The resulting cell suspensions from these two techniques were transferred to a percoll gradient, centrifuged, and lymphocytes were recovered. Flow cytometric analysis of CD45hi cells showed greater percentage of CD44hiCD62lo activated lymphocytes and CD19+ B cells using the dounce method. In addition, we achieved a 3-fold greater recovery of activated virus-specific CD8 T cells specific for the immunodominant Db:VP2121-130 and engineered Kb:OVA257-264 epitopes through manual dounce homogenization approach as compared to collagenase digest. A greater percentage of viable cells was also achieved through dounce homogenization. Therefore, we conclude that manual homogenization is a superior approach to isolate activated T cells from the mouse brain.

Keywords: neuroinflammation, lymphocyte isolation, CNS viral infection, CD8 T cell, Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus, optimized recovery

1. Introduction

Defining effective methods to isolate brain infiltrating T cells in murine models of neurological disease, enables study of their protective and pathogenic roles. Effector T cells are critical to clear bacteria, virus, fungus or parasites infection [1–7]. In addition, CD8 T cells exhibit a protective response against CNS tumors [8, 9]. Conversely, effector T cells can induce autoreactive or immune-mediated diseases, and cause pathologic blood brain barrier disruption [10–13]. For these reasons, there is a necessity to define the quantity and quality of the effector T cells that enter the brain in murine models of neurological disease. Multiple methods have been employed to isolate CD8 T cells from the brain with varying results, necessitating the need for an effective standard approach [14–17].

Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) infection of the CNS enables the study of CD8 T cell responses during acute neuroinflammation. Mouse strains of H-2b,k,d MHC Class I haplotype are resistant to TMEV-induced demyelination and viral persistence [18, 19]. In addition, resistance to TMEV-induced demyelination in H-2b haplotype mice is conferred through expansion of antigen-specific CD8 T cells specific for the immunodominant viral peptide VP2121-130, presented in the Db class I molecule [20, 21]. The expansion of Db:VP2121-130 epitope specific CD8 T cells is highly reproducible during acute TMEV infection of C57BL/6 mice [20, 22]. We therefore employed this established model system to optimize methods of lymphocyte isolation from the brains of TMEV infected C57BL/6 mice.

A crucial step for optimal CD8 T cell isolation is the initial processing of brain tissue for extraction of immune cells. Optimal recovery of infiltrating immune cells is important to achieve cell numbers and quality critical for functional flow cytometric analysis. In this study, we compared manual homogenization versus enzymatic digestion as methods to isolate brain infiltrating lymphocytes (BILs). Brain tissue was processed using a mechanical dounce based approach or digested using type IV collagenase. Our main objective was to identify which approach isolated BILs from the mouse brain most efficiently.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Mice

C57BL/6J males and females at 6–10 weeks of age were obtained from Jackson lab (Bar Harbor, Maine- strain #000664). All animals were used according to the regulations of the Mayo Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2 Virus infection

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and infected intracranially with 2×106 plaque forming units (PFUs) of the Daniel’s strain of TMEV or 2×104 PFUs of TMEV-OVA [23]. Animals were euthanized 7 days after TMEV or TMEV-OVA infection and tissue was collected for flow cytometry analysis.

2.3 Reagents

Db:VP2121-130, Kb:OVA257-264 and Kb:SIYR tetramers were made as previously described to stain for antigen-specific CD8 T cells [20]. The composition of isolated brain infiltrated immune cells was determined by staining with antibodies for CD45 (BD Biosciences #557235), CD8 (BD Biosciences #552877), CD4 (BD Biosciences #553730), CD19 (Southern Biotech #1576-02), CD44 (BD Biosciences #553134) and CD62L (BD Biosciences #561917). Viable cells were identified by negative stain using the viability Ghost Dye Red 780 (Tonbo Biosciences) at a 1:1000 dilution.

2.4 Isolation of brain infiltrating lymphocytes

2.4.1 Dounce homogenization method

Whole brains were extracted and placed in 5 mL of RPMI. Brains were then transferred in 5 mL of RPMI (MediaTech Inc., Herndon, VA) to a 7 mL glass Tenbroeck tissue grinder (Pyrex #7727-07) and homogenized with 10 strokes. Each 5 mL homogenized suspension was then filtered through a 70μm filter (Falcon #352350) into a 50 mL conical tube (Falcon #352098) containing a solution consisting of 1 mL 10X PBS, 9 mL percoll (Sigma-Aldrich GmbH, Steinheim, Germany- #P4937), and 10 mL RPMI. After mixing, cell suspensions were then spun at 7,840 rcf (Thermo Scientific Sorvall Legend XTR- rotor #75003661) for 30 minutes. Myelin and adipose debris were aspirated, and the cell pellet was resuspended into 50 mL conical tubes and diluted with RPMI to a total volume of 50 mL. Cell suspensions were then spun at 300 rcf for 10 minutes (Thermo Scientific Sorvall Legend XTR- rotor #75003607). Media was aspirated off, and cell pellets were resuspended in RPMI media. This process takes approximately 60 minutes for three brains

2.4.2 Collagenase method

Brains were strained through a 70 μm nylon mesh filter, using a 1mL syringe plunger, into RPMI. 700 μg of collagenase type IV (Worthington, Lakewood, NJ- #LS004186) was added to each 5 mL tissue suspension. Suspensions were then incubated in a water bath at 42°C for 45 minutes. After incubation, samples were added to 50 mL conical tubes containing a solution of 1 mL 10X PBS, 9 mL percoll and 10 mL RPMI. After mixing, the cell suspensions were then spun at 7,840 rcf for 30 minutes. Myelin and adipose debris were aspirated and the cell pellet was resuspended into 50 mL conical tubes and diluted with RPMI to a total volume of 50 mL. Cell suspensions were then spun at 300 rcf for 10 minutes. Media was aspirated off, and cell pellets were resuspended in RPMI media. This process takes approximately 120 minutes for three brains. Also, as you increase the amount of brains, the process will take longer due to more tissue samples needing to be enzymatically digest with collagenase.

2.5 Flow Cytometry Analysis

ACK lysis buffer (8.3 g ammonium chloride, 1 g potassium bicarbonate and 37.2 mg EDTA) was added for 2 minutes to remove erythrocytes from samples. To quench the ACK reaction, FACS buffer (1X PBS, 1% FCS and 0.025% sodium azide) was added. Samples were spun at 300 rcf for 2 minutes and the supernatant was discarded. Isolated brain infiltrating lymphocytes were then resuspended in FACS buffer, washed twice, and incubated with Db:VP2121-130 tetramer, Kb:OVA257-264, or Kb:SIYR tetramer for 40 minutes. Cells were also simultaneously stained with antibodies specific to CD45 (0.2 mg/mL), CD4 (0.2 mg/mL), CD19 (0.2 mg/mL), CD44 (0.2 mg/mL) and CD62L (0.5 mg/mL). For experiments that had tetramer staining, anti-CD8α (0.2 mg/mL) was then added during the final 20 minutes of incubation, otherwise CD8 antibody was added at the same time as the other antibodies. The concentration of all antibodies and tetramers was a 1:100 dilution. Cells were then rinsed twice with FACS buffer and fixed in 1% PFA in PBS. Samples were run on a BD LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose CA) and analyzed using FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences, San Jose CA) and FlowJo V10 (FlowJo LLC) (Ashland, OR). GraphPad Prism 6.0 (La Jolla, CA) was used for all statistical analysis.

3. Results

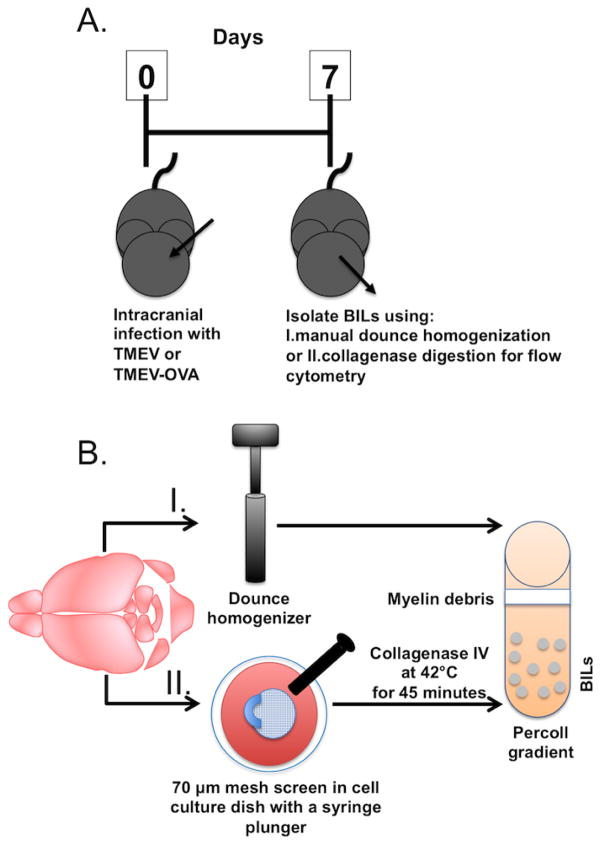

To evaluate our methods of immune cell isolation from the brain, 7 day TMEV infected C57BL/6 mice were euthanized and brains were harvested (Figure 1 A). We collected cell suspensions from the brain using two different methods, dounce homogenization (Figure 1 BI) and collagenase digestion (Figure 1 BII) in addition to centrifugation using a percoll gradient. These samples produced two visible fractions: the upper fraction contained myelin and other debris. The lower fraction was enriched for immune cells and erythrocytes. The lower fraction was harvested, erythrocytes were lysed with ACK buffer, and the lymphocyte population was analyzed by flow cytometry.

Figure 1.

Timeline for TMEV infection and isolation methods to recover BILs. (A) On day zero, C57BL/6 mice are infected intracranially with TMEV or TMEV-OVA. Seven days post-infection brain tissue is extracted and brain infiltrating lymphocytes (BILs) are isolated and processed for flow cytometric analysis. (B) Brain tissue was harvested with one of two methods. The first method (I) is by manual dounce homogenization. The second method (II) is by dissociation using a 70μm mesh screen with a 1 mL syringe plunger, followed by incubation at 42°C for 45 minutes with collagenase IV. After both methods of sample processing, brain homogenate was transferred to a percoll gradient for centrifugation to eliminate myelin debris and erythrocytes from solution.

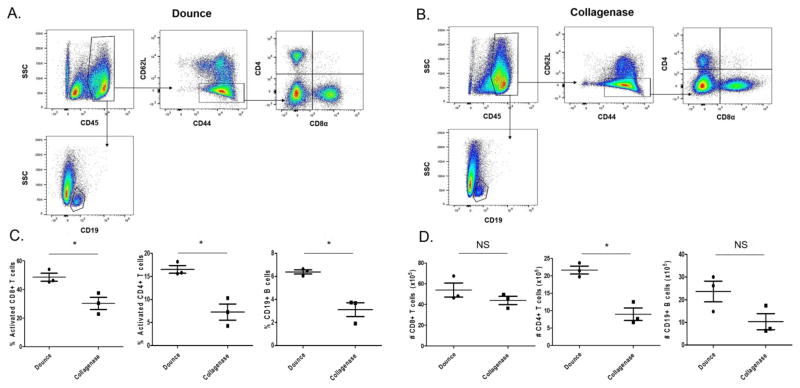

3.1 Higher frequency of activated, lymphocytes is obtained using the dounce method of isolation from 7 day TMEV infected C57BL/6 mice

We analyzed CD45hi cells isolated from manual dounce homogenization and collagenase digestion techniques. The CD45hi population was selected for further analysis to exclude the microglia (CD45low) population. The CD45hi population includes all infiltrating hematopoietic derived immune cells. We obtained a higher frequency of activated CD8 T cells, CD4 T cells, and CD19 B cells using manual dounce homogenization then with collagenase type IV digestion as a percentage of CD45hi cells (Figure 2). Flow cytometric analysis revealed we obtained a higher percentage of CD44hiCD62lo activated CD8 and CD4 lymphocytes, as well as CD19 B cells using the manual dounce method when compared to collagenase digestion technique (Figure 2 C). However, there is not a significant difference in the total number of infiltrating CD8 T cells (p=0.2647) or CD19 B cells (p=0.0823) in the brain tissue (Figure 2 D). Whereas there is a significantly higher number of CD4 T cells (p=0.0041) in the dounce treated samples.

Figure 2.

Higher percentage of activated, lymphocytes using manual dounce method when compared to collagenase digest method of isolation. C57BL/6 mice were intracranially infected with TMEV and brains were harvested 7 days later for analysis by flow cytometry. A) Representative gating strategy of BILs isolated by dounce method or B) collagenase method. C) Quantification of percent activated (CD44hiCD62Llo) CD8 T cells, activated (CD44hiCD62Llo) CD4 T cells, and CD19 B cells gated on CD45hi cells. D) Quantification of absolute numbers of CD8+, CD4+, and CD19+ lymphocytes. All quantified populations were gated on singlets, viability, and lymphocyte size and scatter profile. (n = 3) Error bars represent mean ± SEM (*p<0.05).

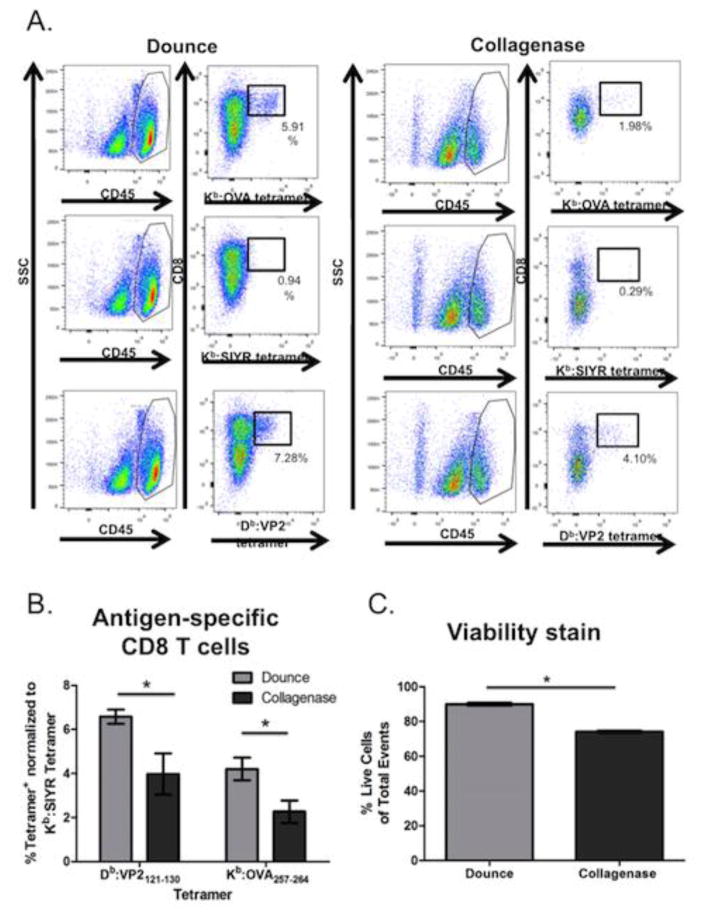

3.2 Higher quantities of antigen-specific CD8 T cells are isolated using the dounce method of isolation from 7 day TMEV infected C57BL/6 mice

In addition to analyzing Db:VP2121-130 epitope specific CD8 T cells, we tested the recovery of antigen-specific CD8 T cells specific for the Kb:OVA257-264 epitope following TMEV-OVA infection (Figure 3). TMEV-OVA is a recombinant TMEV virus encoding the OVA257-264 model epitope, SIINFEKL, in the leader sequence of the virus [23]. The OVA257-264 peptide is presented in the context of Kb class I molecule, which enables analysis of an additional MHC class I molecule besides Db in our protocols. Using Db:VP2121-130 and Kb:OVA257-264 tetramer staining, we determined the percentage of Db:VP2121-130 and Kb:OVA257-264 epitope specific CD8 T cells separately recovered using the dounce homogenization and collagenase based methods of lymphocyte isolation (Figure 3 A, B). Our results are consistent with data presented in Figure 2, in that the dounce method of isolation enables greater recovery of activated CD8 T cells. We also determined that dounce homogenization preserved cell viability during isolation compare to the collagenase digest based method (Figure 3 C).

Figure 3.

Higher recovery of Db:VP2121-130 and Kb:OVA257 -264 epitope-specific CD8 T cells using the dounce method isolation. C57BL/6 mice were intracranially infected with TMEV and brains were harvested seven days later for analysis by flow cytometry. A) Representative gating strategy of BILs isolated by the dounce or collagenase method. B) Quantification of antigen-specific (Db:VP2121-130, Kb:OVA257 -264 or negative staining control Kb:SIYR tetramer+) CD8 T cells gated on CD45hi cell population. C) Quantification of live CD8 T cells of CD45hi cells. (n = 8) Error bars represent mean ± SEM. (p<0.05)

4. Discussion

Determining the optimal method to isolate brain infiltrating T cells is crucial for the study of murine models of neurologic disease. The studies presented here demonstrate superior isolation of antigen-specific brain infiltrating T cells using manual dounce homogenization technique when compared to collagenase digest. Dounce homogenization achieves a higher yield of activated, antigen-specific, viable CD8 T cells along with a greater percentage of activated CD4 T cells and CD19 B cells. In addition, the dounce method allows for quicker brain tissue processing as compared to the enzymatic digestion method with collagenase type IV. This decrease, in total time required from freshly isolated brain tissue to isolated immune cell types for flow cytometric analysis, is beneficial for preserving cell viability and increased accuracy of CNS infiltrating immune cells.

Multiple methods have been employed to isolated brain infiltrating CD8 T cells responses. The collagenase based approach has been employed by our laboratory as well as others as a standard method to isolate brain-infiltrating lymphocytes [8, 16, 17, 24–29]. Manual homogenization has also been employed among various research laboratories as a method of brain-infiltrating lymphocyte isolation as well [15, 30, 31]. The results obtained from this study demonstrate there are differences in the two isolation methods pertaining to purity, yield and viability of brain infiltrating antigen-specific CD8 T cells using acute TMEV infection as a model. Dounce homogenization is superior in all three of these metrics.

Previously, Deb et al. also compared two methods to isolate infiltrating immune cells from the spinal cord of chronic TMEV infected mice [32]. In this study, authors compared a non-enzymatic method: Tenbroeck tissue grinder homogenizer and an enzymatic method: type IV clostridial collagenase. Consistent with our studies analyzing the brain, more effector CD8 T cells were recovered from the spinal cord using the manual based homogenization. This group also achieved a higher recovery of spinal cord infiltrating T cells using this manual homogenization technique. Therefore, despite structural differences in the tissue comprising brain and spinal cord, we contend a manual homogenization technique should be employed for both components of the CNS.

The reduced Db:VP2121-130 tetramer staining observed using the collagenase based method of BILs isolation is indicative of reduced recovery of antigen-specific CD8 T cells (Figure 3). Therefore, it is possible that enzymatic digestion may also alter, degrade, or cleave the T cell receptor (TCR) from the surface of CD8 T cells. The loss of TCR would impact our ability to recovery and quantify antigen-specific CD8 T cells, which are now undetectable by tetramer staining. Finally, since collagenase digest takes longer and exposes T cells to warmer temperature, it is possible this also affects T cell viability. Regardless of the exact mechanism by which collagenase decreases CD8 T cell yield, proper isolation of BILs could affect the phenotypic characterization of the immune response as well as affect ex vivo assays performed using enriched immune cell populations. In summary, we contend the manual based approach for the isolation of brain infiltrating lymphocytes in neuroinflammation studies moving forward.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Fang Jin and Robin Willenbring for their help and assistance in the experiments. Also, thanks to Michael Hansen for his help and advice with the mouse work, and Dr. Kevin Pavelko for providing the TMEV-OVA virus (Mayo Clinic Immunology Department). Funding for this project was supported by NIH RO1-94168001 and NIH R21 CA186976.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Alexander-Miller MA. High-avidity CD8+ T cells: optimal soldiers in the war against viruses and tumors. Immunol Res. 2005;31(1):13–24. doi: 10.1385/IR:31:1:13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altenburg AF, Rimmelzwaan GF, de Vries RD. Virus-specific T cells as correlate of (cross-)protective immunity against influenza. Vaccine. 2015;33(4):500–6. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen K, Kolls JK. T cell-mediated host immune defenses in the lung. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013;31:605–33. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-100019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huffnagle GB, Yates JL, Lipscomb MF. Immunity to a pulmonary Cryptococcus neoformans infection requires both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1991;173(4):793–800. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.4.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lewinsohn DA, Gold MC, Lewinsohn DM. Views of immunology: effector T cells. Immunol Rev. 2011;240(1):25–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rossey I, et al. CD8+ T cell immunity against human respiratory syncytial virus. Vaccine. 2014;32(46):6130–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.08.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walker DH. Rickettsiae and rickettsial infections: the current state of knowledge. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(Suppl 1):S39–44. doi: 10.1086/518145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Renner DN, et al. Effective Treatment of Established GL261 Murine Gliomas through Picornavirus Vaccination-Enhanced Tumor Antigen-Specific CD8+ T Cell Responses. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0125565. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Renner DN, et al. Improved Treatment Efficacy of Antiangiogenic Therapy when Combined with Picornavirus Vaccination in the GL261 Glioma Model. Neurotherapeutics. 2016;13(1):226–36. doi: 10.1007/s13311-015-0407-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belnoue E, et al. On the pathogenic role of brain-sequestered alphabeta CD8+ T cells in experimental cerebral malaria. J Immunol. 2002;169(11):6369–75. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.11.6369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goverman J. Autoimmune T cell responses in the central nervous system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(6):393–407. doi: 10.1038/nri2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goverman JM. Immune tolerance in multiple sclerosis. Immunol Rev. 2011;241(1):228–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01016.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suidan GL, et al. Induction of blood brain barrier tight junction protein alterations by CD8 T cells. PLoS One. 2008;3(8):e3037. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berghmans N, et al. Rescue from acute neuroinflammation by pharmacological chemokine-mediated deviation of leukocytes. J Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:243. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campanella M, et al. Flow cytometric analysis of inflammatory cells in ischemic rat brain. Stroke. 2002;33(2):586–92. doi: 10.1161/hs0202.103399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Legroux L, et al. An optimized method to process mouse CNS to simultaneously analyze neural cells and leukocytes by flow cytometry. J Neurosci Methods. 2015;247:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2015.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sedgwick JD, et al. Isolation and direct characterization of resident microglial cells from the normal and inflamed central nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88(16):7438–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Altintas A, et al. Differential expression of H-2K and H-2D in the central nervous system of mice infected with Theiler’s virus. J Immunol. 1993;151(5):2803–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patick AK, et al. Major histocompatibility complex-conferred resistance to Theiler’s virus-induced demyelinating disease is inherited as a dominant trait in B10 congenic mice. J Virol. 1990;64(11):5570–6. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.11.5570-5576.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson AJ, et al. Prevalent class I-restricted T-cell response to the Theiler’s virus epitope Db:VP2121-130 in the absence of endogenous CD4 help, tumor necrosis factor alpha, gamma interferon, perforin, or costimulation through CD28. J Virol. 1999;73(5):3702–8. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3702-3708.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mendez-Fernandez YV, et al. Clearance of Theiler’s virus infection depends on the ability to generate a CD8+ T cell response against a single immunodominant viral peptide. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33(9):2501–10. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson AJ, et al. Preservation of motor function by inhibition of CD8+ virus peptide-specific T cells in Theiler’s virus infection. FASEB J. 2001;15(14):2760–2. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0373fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pavelko KD, et al. Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus as a vaccine candidate for immunotherapy. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e20217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deckert-Schluter M, et al. Interferon-gamma receptor-mediated but not tumor necrosis factor receptor type 1- or type 2-mediated signaling is crucial for the activation of cerebral blood vessel endothelial cells and microglia in murine Toxoplasma encephalitis. Am J Pathol. 1999;154(5):1549–61. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65408-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson HL, et al. CD8 T cell-initiated blood-brain barrier disruption is independent of neutrophil support. J Immunol. 2012;189(4):1937–45. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson HL, et al. Perforin competent CD8 T cells are sufficient to cause immune-mediated blood-brain barrier disruption. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e111401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDole JR, et al. Rapid formation of extended processes and engagement of Theiler’s virus-infected neurons by CNS-infiltrating CD8 T cells. Am J Pathol. 2010;177(4):1823–33. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reichmann G, et al. The CD28/B7 interaction is not required for resistance to Toxoplasma gondii in the brain but contributes to the development of immunopathology. J Immunol. 1999;163(6):3354–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schluter D, et al. Expression pattern and cellular origin of cytokines in the normal and Toxoplasma gondii-infected murine brain. Am J Pathol. 1997;150(3):1021–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deb C, et al. Demyelinated axons and motor function are protected by genetic deletion of perforin in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68(9):1037–48. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181b5417e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Howe CL, et al. Inflammatory monocytes damage the hippocampus during acute picornavirus infection of the brain. J Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:50. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deb C, Howe CL. Functional characterization of mouse spinal cord infiltrating CD8+ lymphocytes. J Neuroimmunol. 2009;214(1–2):33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]