Abstract

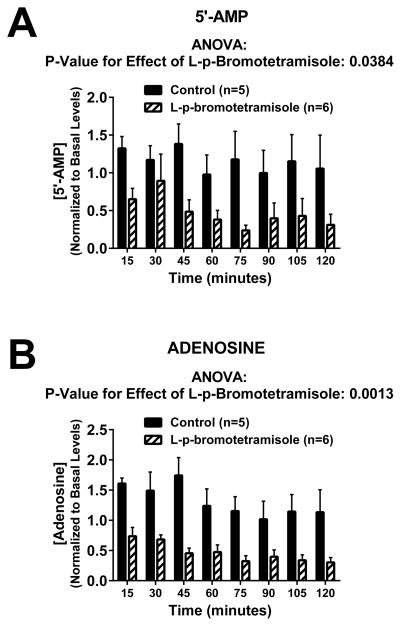

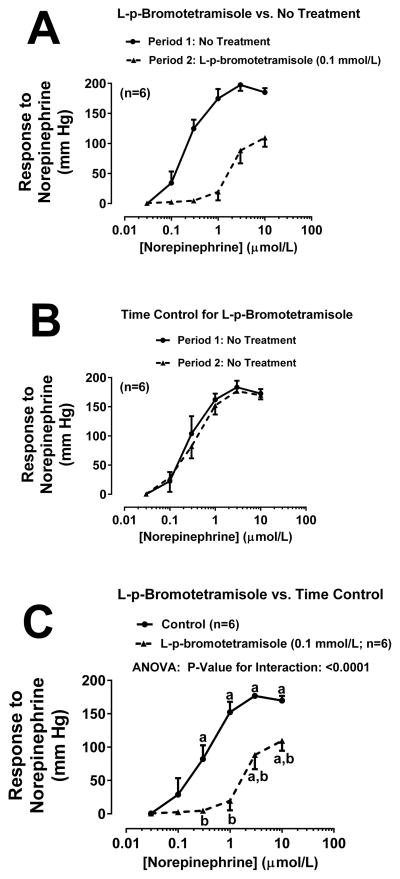

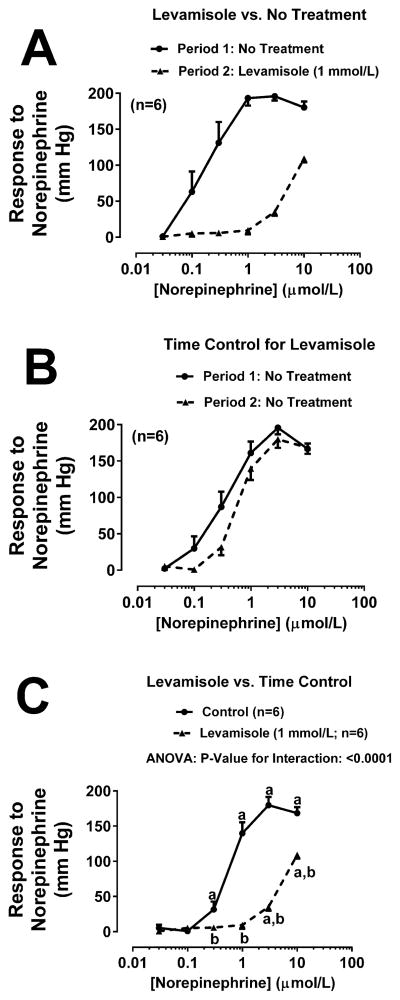

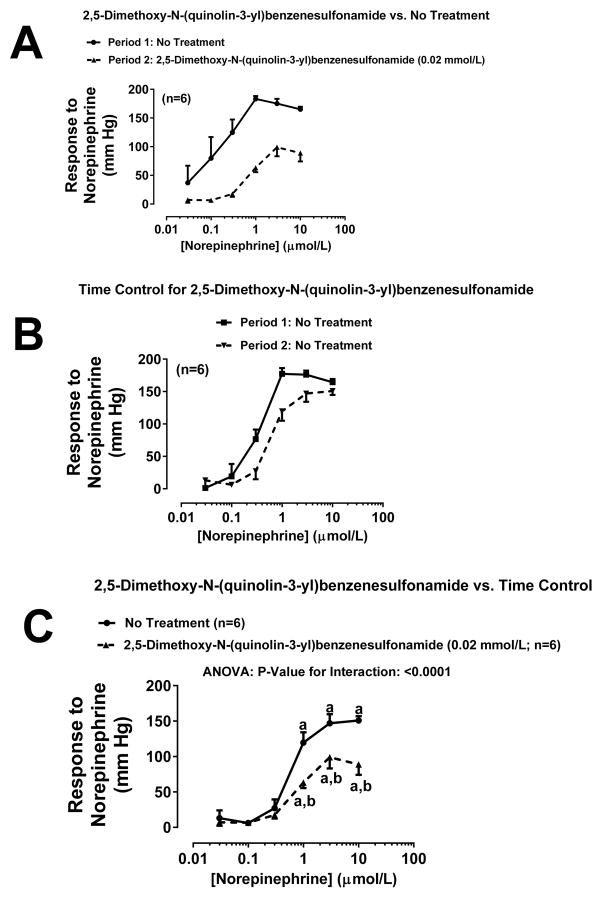

Tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase (TNAP) contributes to the production of adenosine by the kidney, and A1-receptor activation enhances renovascular responses to norepinephrine. Therefore, we hypothesized that TNAP regulates renovascular responsiveness to norepinephrine. In isolated, perfused rat kidneys, the TNAP inhibitor L-p-bromotetramisole (0.1 mmol/L) decreased renal venous levels of 5′-AMP (adenosine precursor) and adenosine by 61% (P<0.0384) and 62% (P=0.0013), respectively, at 1 hour into treatment, and caused a 10-fold rightward shift of the concentration-response relationship to exogenous norepinephrine (P<0.0001). Similarly, two other TNAP inhibitors, levamisole (1 mmol/L) and 2,5-dimethoxy-N-(quinolin-3-yl)benzenesulfonamide (0.02 mmol/L), also right-shifted the concentration-response relationship to norepinephrine. The ability of TNAP inhibition to blunt renovascular responses to norepinephrine was mostly prevented or reversed by restoring A1-adenosinergic tone with the A1-receptor agonist 2-chloro-N6-cyclopentyladenosine (100 nmol/L). All three TNAP inhibitors also attenuated renovascular responses to renal sympathetic nerve stimulation, suggesting that TNAP inhibition attenuates renovascular responses to endogenous norepinephrine. In control propranolol-pretreated rats, acute infusions of norepinephrine (10 μg/kg/min) increased mean arterial blood pressure from 95±5 to a peak of 169±4 mm Hg, and renovascular resistance from 12±2 to a peak of 55±12 mm Hg/ml/min; however, in rats also treated with intravenous L-p-bromotetramisole (30 mg/kg), the pressor and renovascular effects of norepinephrine were significantly attenuated (blood pressure: basal and peak, 93±7 and 146±6 mm Hg, respectively; renovascular resistance: basal and peak, 13±2 and 29±5 mm Hg/ml/min, respectively). Conclusion: TNAP inhibitors attenuate renovascular and blood pressure responses to norepinephrine suggesting that TNAP participates in the regulation of renal function and blood pressure.

Keywords: Tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase, norepinephrine, renal vasoconstriction, L-p-bromotetramisole, adenosine, A1 receptors

INTRODUCTION

Previously we discovered that activation of A1 receptors by endogenous adenosine modulates renovascular responses to renal sympathetic nerve stimulation (RSNS) and to exogenous norepinephrine1, 2. This conclusion is supported by our observations that in isolated, perfused rat kidneys selective A1-receptor antagonism reduces renovascular responses to RSNS1 and that in isolated, perfused mouse kidneys A1-receptor deletion suppresses renovascular responses to RSNS and exogenous norepinephrine (NE)2. Mechanistically, there are 3 reasons A1 receptors contribute to RSNS-induced renal vasoconstriction: 1) RSNS triggers adenosine formation2–4; 2) preglomerular microvessels express high levels of vasoconstrictor A1 receptors5; and 3) in the renal vasculature, the Gi signaling pathway (which adenosine acting via the A1 receptor engages) converges with the Gq signaling pathway (which NE acting via the α1-adrenoceptors engages) to trigger “coincident signaling” at phospholipase C leading to augmentation by adenosine of the renovascular response to released NE1. These facts may explain why most of the RSNS-induced increase in renovascular resistance is due to contraction of the preglomerular microcirculation6 (where A1 receptors are highly expressed).

Because ATP is released from noradrenergic varicosities7–10, as well as from vascular smooth muscle11, 12 and endothelial cells13–16, the main precursor of adenosine in the renal vasculature is most likely ATP. CD39 catalyzes the metabolism of ATP to ADP and ADP to 5′-AMP, and CD73 metabolizes 5′-AMP to adenosine; thus these twin ecto-enzymes acting in tandem are justifiably considered the most important mechanism for producing extracellular adenosine from ATP17–20. Surprisingly, however, our experiments show that in isolated, perfused mouse kidneys, neither pharmacological inhibition nor genetic deletion of CD73 attenuates renovascular responses to RSNS21. Moreover, our unpublished experiments show that in mouse kidneys even extremely high concentrations (100 μmol/L) of the potent CD39 inhibitor ARL67158 have no effect on renovascular responses to RSNS.

To reconcile our findings we hypothesize that although CD39 and CD73, acting in tandem, provide the most important pathway of adenosine production in most biological contexts, this may not be true for all biological compartments. In this regard, it is important to note that tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase (TNAP) is in many ways like CD7322. Both of these ecto-enzymes are GPI-anchored to cell membranes with the catalytic domains facing the extracellular space, contain metal ions (e.g., Zn2+), are glycosylated, have similar molecular weights, form homomeric dimers, are widely expressed, can be released as soluble forms, and can catalyze conversion of AMP to adenosine22. However, unlike CD73, TNAP does not require CD39 to complete the ATP to adenosine pathway; i.e., the entire biochemical pathway (ATP → ADP → 5′-AMP → adenosine) can be accomplished by TNAP23.

Because CD39 and CD73 do not appear to be involved in producing the adenosine that regulates renal sympathetic neurotransmission and because TNAP mRNA, protein and activity are present in kidneys and TNAP contributes to the metabolism of 5′-AMP to adenosine in kidneys24, TNAP may be involved in modulating renovascular responses to norepinephrine. We therefore hypothesized that TNAP inhibition would attenuate renovascular responses to exogenous NE presented to the luminal aspect of renal blood vessels and to endogenous NE presented to the abluminal side of renal blood vessels via RSNS.

METHODS

Materials

Levamisole, 2,5-dimethoxy-N-(quinolin-3-yl)benzenesulfonamide, 2-chloro-N6-cyclopentyladenosine (CCPA) and NE were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). L-p-bromotetramisole was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX).

Animals

This study employed male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River; Wilmington, MA) that were approximately 16 weeks of age. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all procedures. The investigation conforms to National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Isolated, Perfused Rat Kidney

Rats were anesthetized with thiobutabarbital (100 mg/kg, intraperitoneal injection). Kidneys were isolated without interruption of perfusion, transferred to a Hugo Sachs Elektronik-Harvard Apparatus GmbH (March-Hugstetten, Germany) kidney perfusion system and perfused at 5 ml/min (constant flow) with oxygenated (95% O2/5% CO2) Tyrode’s solution (in mM: NaCl, 137.0; KCl, 2.7; CaCl2, 1.8; MgCl2, 1.1; NaHCO3, 12.0; NaH2PO4, 0.42; and D(+)-glucose, 5.6). The kidney perfusion system included the following components: Model UP 100 Universal Perfusion System; Model ISM 834 Channel Reglo Digital Roller Pump; a glass double-walled perfusate reservoir maintained at 37°C and oxygenated; a R 120144 glass-oxygenator maintained at 37°C; mechanical integration of the oxygenator with the Universal Perfusion System UP 100; a Windkessel for absorption of pulsations; an inline holder for disc particle filters (80 microns); a temperature controlled plexiglass kidney chamber integrated with the UP 100; and a thermostatic circulator. The plexiglass chamber contained a heat exchanger to maintain the temperature of the perfusate at 37°C at the point of entry into the tissue, and also contained a device to extract bubbles from the perfusate just before the perfusate entered the kidney. Perfusion pressure was monitored with a pressure transducer and recorded on a polygraph.

Analysis of 5′-AMP and Adenosine

5′-AMP and adenosine were quantified using ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry, using our most recently updated version of the assay25.

Protocol 1

Rat kidneys were isolated and perfused as described above and allowed to stabilize for 30 minutes. Renal venous samples were collected at baseline, and then at 15-minute intervals after treatment with either vehicle (Tyrode’s solution) or L-p-bromotetramisole (0.1 mmol/L). The samples were immediately heat inactivated (i.e., placed in a heating block at 100°C for 90 seconds) to denature any enzymes that might degrade 5′-AMP or adenosine. Samples were stored at −80°C until assayed for 5′-AMP and adenosine as described above.

Protocol 2

In this and all protocols described below, the concentrations provided are final concentrations of the substance in the perfusate entering the kidney. Rat kidneys were isolated and perfused as described above and allowed to stabilize for 30 minutes. Next, NE was administered to the kidney at 0.03, 0.1, 0.3, 3 and 10 μmol/L for 5 minutes at each concentration and the change in perfusion pressure from the initial baseline was recorded (i.e., cumulative concentration-perfusion pressure response experiment; Period 1). After a 30-minute washout, an inhibitor of TNAP was administered as follows: L-p-bromotetramisole, 0.1 mmol/L; levamisole, 1 mmol/L; or 2,5-dimethoxy-N-(quinolin-3-yl)benzenesulfonamide, 0.02 mmol/L. Each kidney received only a single TNAP inhibitor. The concentrations of TNAP inhibitors were selected on the basis of published concentrations of each necessary to inhibit TNAP26–28. After 15 minutes, the cumulative concentration-perfusion pressure response experiment to NE was repeated in the presence of the TNAP inhibitor (Period 2). For each TNAP inhibitor, a time-control group of kidneys was randomized into the protocol. In these groups, the experiment was identical to that described above, except that no inhibitors were administered during Period 2.

Protocol 3

Rat kidneys were isolated and perfused as described above and allowed to stabilize for 30 minutes. After stabilization, baseline perfusion pressures were recorded and then NE was infused (0.5 μmol/L) for 5 minutes and perfusion pressures were again recorded. After a 15 minute recovery period, kidneys were treated with the TNAP inhibitor L-p-bromotetramisole (0.1 mmol/L) and this treatment was continued for the remainder of the experiment. After 15 minutes, perfusion pressures were again recorded before and 5 minutes into an infusion of NE (0.5 μmol/L). Next, kidneys were treated with the highly selective A1 receptor agonist CCPA29 (100 nmol/L), and the CCPA treatment was continued for the remainder of the protocol. After 15 minutes, perfusion pressures were again recorded before and 5 minutes into an infusion of NE (0.5 μmol/L).

Protocol 4

Rat kidneys were isolated and perfused as described above and allowed to stabilize for 30 minutes. Next, kidneys were treated with the highly selective A1 receptor agonist CCPA (100 nmol/L), and the CCPA treatment was continued for the remainder of the protocol. After 5 minutes, perfusion pressures were recorded before and 5 minutes into an infusion of NE (0.5 μmol/L). The NE treatment was stopped, then after 5 minutes kidneys were treated with the TNAP inhibitor L-p-bromotetramisole (0.1 mmol/L) and this treatment was continued for the remainder of the experiment. After 5 minutes, perfusion pressures were again recorded before and 5 minutes into an infusion of NE (0.5 μmol/L).

Protocol 5

Rat kidneys were isolated and perfused as described above. Immediately after initiating perfusion of the kidney, a platinum bipolar electrode was positioned around the renal artery close to the kidney for renal nerve stimulation, and the electrode was connected to a Grass stimulator (model SD9E; Grass Instruments). After 30 minutes of stabilization, a response to RSNS was elicited at 5 Hz for 2 minutes. This response was used to normalize subsequent responses so as to reduce variability due to kidney-to-kidney differences in contact of the electrodes with periarterial sympathetic nerves. Next, some kidneys were treated with an inhibitor of TNAP as follows: L-p-bromotetramisole, 0.1 mmol/L; levamisole, 1 mmol/L; or 2,5-dimethoxy-N-(quinolin-3-yl)benzenesulfonamide, 0.02 mmol/L. Each kidney received only a single TNAP inhibitor. Fifteen minutes after starting the TNAP inhibitor treatments, a frequency-perfusion pressure response relationship was generated by periarterial nerve stimulation at 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 Hz for 2 minutes at 15-minute intervals. For each TNAP inhibitor group, a time-control group of kidneys was randomized into the protocol. In these groups, the experiment was identical to that described above, except that no inhibitors were administered.

Protocol 6

To determine whether TNAP inhibition alters renal levels of phosphate, perfused kidneys were treated with L-p-bromotetramisole (0.1 mmol/L) and phosphate levels in kidney perfusate were measured before and during treatment with L-p-bromotetramisole using the Abcam (Cambridge, MA) fluorometric phosphate assay kit (cat# ab102508).

Protocol 7

To determine whether NE regulates the release of TNAP, TNAP activity (Abcam alkaline phosphatase assay Kit, cat# ab83369) was measured in renal venous perfusate collected before and after treatment with NE (0.5 μmol/L for 5 minutes) in both naïve kidneys and kidneys pretreated with CCPA (0.1 μmol/L beginning 10 minutes before administering NE).

Protocol 8

Rats were anesthetize with thiobutabarbital (100 mg/kg, intraperitoneal injection) and pretreated with propranolol (3 mg/kg, subcutaneous injection) to prevent NE-induced activation of β-adrenoceptors. Body temperature was monitored with a rectal temperature probe and maintained with an isothermal pad and heat lamp. Polyethylene (PE) cannulas were inserted into the trachea (PE-240) to facilitate respiration and into the carotid artery (PE-50) for measurement of mean arterial blood pressure (MABP) using a digital blood pressure analyzer (BPA 200, Micro-Med, Inc., Louisville, KY). Also, two PE-10 cannula were inserted into the jugular vein (one for administration of NE and the other for administration of L-p-bromotetramisole). An intravenous infusion of 0.9% saline (50 μl/min) was initiated to maintain volume status. Next, a transit-time flow probe (Model 1RB; Transonic Systems, Inc., Ithaca, NY) was placed on the left renal artery to monitor renal blood flow (RBF) using a Transonic flowmeter. After a 30-minute stabilization period, rats were treated with either two intravenous slow-bolus injections (separated by 15 minutes) of vehicle (saline) or L-p-bromotetramisole (total dose, 30 mg/kg). Administering the L-p-bromotetramisole as two slow injections minimized basal blood pressure perturbations. Fifteen minutes after the second bolus of L-p-bromotetramisole, NE was infused at 10 μg/kg/min for 10 minutes.

Protocol 9

Preglomerular vascular smooth muscle cells (PGVSMCs) and preglomerular vascular endothelial cells (PGVECs) were isolated and placed in cell culture as previously described30, 31. Cell protein extracts were obtained, and TNAP expression in PGVSMCs and PGVECs was determined and compared using western blotting as previously described32. The primary antibody was Abcam’s anti-TNAP antibody (Cat# ab65834).

Statistics

Values are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using appropriate models of analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) test if the overall effects or interactions in the ANOVA were significant. A paired Student’s t-test was employed for comparing two means in the same group of rats. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Protocol 1

To confirm that TNAP inhibition reduces adenosine production by rat kidneys, renal venous samples was collected at baseline, and then at 15-minute intervals after treatment with either vehicle (Tyrode’s solution; n=6) or L-p-bromotetramisole (0.1 mmol/L; n=6). Samples were analyzed for 5′-AMP (immediate adenosine precursor) and adenosine by ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry25. As shown in Figure 1, L-p-bromotetramisole caused a significant and sustained reduction in the renal venous levels of 5′-AMP (Figure 1A; P<0.04) and adenosine (Figure 1B; P<0.002). In another 3 perfused kidneys, we observed that renal venous adenosine was 120 ± 9 ng/ml before versus 47 ± 7 ng/ml (P<0.02) 15 minutes after administration of an alternative TNAP inhibitor (levamisole; 1 mmol/L); similarly, in yet another 3 perfused kidneys, renal venous adenosine was 110 ± 18 ng/ml before and 39 ± 8 ng/ml (P<0.03) 15 minutes after administration of the TNAP inhibitor 2,5-dimethoxy-N-(quinolin-3-yl)benzenesulfonamide (0.02 mmol/L).

Figure 1. Effects of L-p-bromotetramisole on purine release.

Bar graphs depict the effects of L-p-bromotetramisole (0.1 mmol/L) on renal venous levels of 5′-AMP (Panel A) and adenosine (Panel B) in isolated, perfused rat kidneys. Values are means and SEMs. Data were analyzed using a repeated measures 2-factor ANOVA.

Protocol 2

Figure 2A shows the concentration-response curve to NE (0.03, 0.1, 0.3, 3 and 10 μmol/L for 5 minutes at each concentration) before (Period 1) and during (Period 2) treatment with the TNAP inhibitor L-p-bromotetramisole (0.1 mmol/L). As shown, there was an approximate 30-fold shift in the NE concentration-response curve between Period 1 and Period 2. To assess whether the shift in the NE concentration-response curve between Period 1 and Period 2 was due to a time-related degradation of the experimental preparation, we randomized into the experimental series a group of kidneys that did not receive treatment either during Period 1 or Period 2 (Figure 2B). In this group there was slight shift that could be attributed to time-related changes in responsiveness to NE. Since there was a slight time-related shift in the concentration-response curve, we compared statistically the concentration-response curves to NE during Period 2 of panel A and B. As shown in Figure 2C, even using this more conservative statistical approach, L-p-bromotetramisole induced a significant (P<0.0001) shift in the NE concentration-response relationship. To further challenge our hypothesis, we repeated the experiment summarized in Figure 2 except rather than using L-p-bromotetramisole to inhibit TNAP, we used either levamisole (1 mmol/L; Figure 3) or 2,5-dimethoxy-N-(quinolin-3-yl)benzenesulfonamide (0.02 mmol/L; Figure 4). New time controls were randomized into each of the TNAP inhibitor groups. As shown in Figure 3A and Figure 4A treatment with either levamisole or 2,5-dimethoxy-N-(quinolin-3-yl)benzenesulfonamide, respectively, markedly shifted the NE concentration curve, whereas the shift due to time was much less (Figure 3B and 4B, respectively). Using the same statistical approach as with L-p-bromotetramisole, both alternative TNAP inhibitors significantly (P<0.0001) right-shifted the NE concentration response relationship (Figure 3C and 4C for levamisole and 2,5-dimethoxy-N-(quinolin-3-yl)benzenesulfonamide, respectively).

Figure 2. Effects of L-p-bromotetramisole on renovascular responses to norepinephrine.

Panel A: L-p-bromotetramisole (0.1 mmol/L) was administered between Periods 1 and 2. Panel B: No treatments were administered between Periods 1 and 2. Panel C: Period 2 of panel A is compared to Period 2 of panel B by repeated measures 2-factor ANOVA. aSignificant difference (P<0.05; Fisher’s LSD test) within a group between indicated concentration of norepinephrine versus lowest concentration of norepinephrine. bSignificant difference (P<0.05; Fisher’s LSD test) between groups at indicated concentration of norepinephrine. Values are means and SEMs.

Figure 3. Effects of levamisole on renovascular responses to norepinephrine.

Panel A: Levamisole (1 mmol/L) was administered between Periods 1 and 2. Panel B: No treatments were administered between Periods 1 and 2. Panel C: Period 2 of panel A is compared to Period 2 of panel B by repeated measures 2-factor ANOVA. aSignificant difference (P<0.05; Fisher’s LSD test) within a group between indicated concentration of norepinephrine versus lowest concentration of norepinephrine. bSignificant difference (P<0.05; Fisher’s LSD test) between groups at indicated concentration of norepinephrine. Values are means and SEMs.

Figure 4. Effects of 2,5-dimethoxy-N-(quinolin-3-yl)benzenesulfonamide on renovascular responses to norepinephrine.

Panel A: 2,5-Dimethoxy-N-(quinolin-3-yl)benzenesulfonamide (0.02 mmol/L) was administered between Periods 1 and 2. Panel B: No treatments were administered between Periods 1 and 2. Panel C: Period 2 of panel A is compared to Period 2 of panel B by repeated measures 2-factor ANOVA. aSignificant difference (P<0.05; Fisher’s LSD test) within a group between indicated concentration of norepinephrine versus lowest concentration of norepinephrine. bSignificant difference (P<0.05; Fisher’s LSD test) between groups at indicated concentration of norepinephrine. Values are means and SEMs.

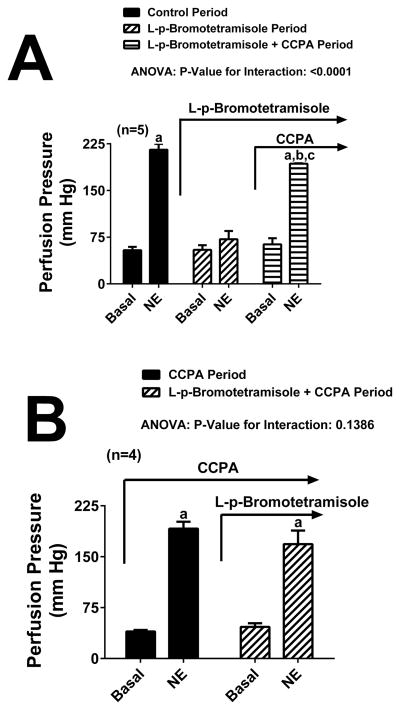

Protocol 3

Figure 5A illustrates the ability of the highly selective A1 receptor agonist CCPA (100 nmol/L) to reverse most of the inhibitory effect of L-p-bromotetramisole (0.1 mmol/L) on the renovascular response to NE (0.5 μmol/L). As expected, NE significantly increased perfusion pressure. Although L-p-bromotetramisole did not alter basal perfusion pressure, this TNAP inhibitor nearly abolished the response to NE. Importantly, administration of CCPA to kidneys receiving L-p-bromotetramisole reversed most of the suppression of NE responses induced by L-p-bromotetramisole.

Figure 5. Reversal and prevention of L-p-bromtetramisole-induced inhibition of renovascular responses to norepinephrine.

Bar graphs depict the ability of the highly selective A1-receptor agonist 2-chloro-N6-cyclopentyladenosine (CCPA; 100 nmol/L) to reverse (Panel A) or prevent (Panel B) the inhibitory effects of L-p-bromotetramisole (0.1 mmol/L) on renovascular responses to exogenous norepinephrine (NE; 0.5 μmol/L). Data were analysed by repeated measures 1-factor ANOVA. aSignificant difference (P<0.05; Fisher’s LSD test) versus corresponding basal perfusion pressure. b,cSignificant difference (P<0.05; Fisher’s LSD test) versus the perfusion pressures during the 1st and 2nd administrations of NE, respectively. Values are means and SEMs.

Protocol 4

Protocol 3 showed that CCPA could reverse most of the inhibitory effects of L-p-bromotetramisole on renovascular repsonses to NE. The purpose of Protocol 4 was to determine whether pretreatment with CCPA could prevent most of the inhibitory effect of L-p-bromotetramisole on renovascular responses to NE. As shown in Figure 5B, in the presence of CCPA, NE significantly increased perfusion pressure. L-p-bromotetramisole plus CCPA did not alter basal perfusion pressure. Moreover, in the presence of CCPA, L-p-bromotetramisole had little effect on NE-induced renovascular responses.

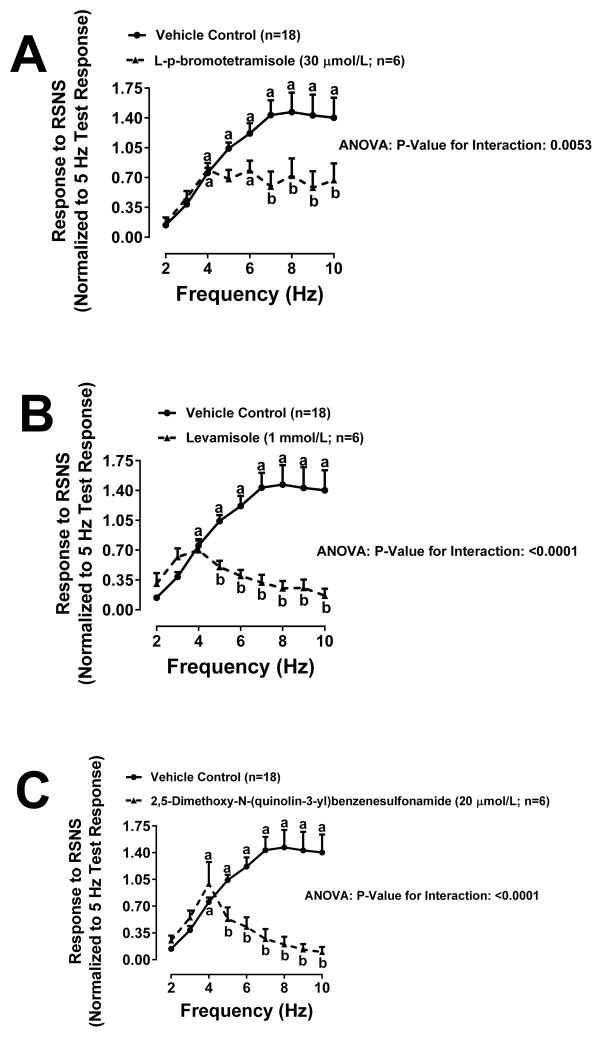

Protocol 5

In Protocol 5, RSNS-induced responses were elicited in isolated, perfused rat kidneys. In this regard, at the beginning of each experiment, a response to RSNS was elicited at 5 Hz for 2 minutes, and this response was used to normalize subsequent responses so as to reduce variability due to kidney-to-kidney differences in contact of the electrodes with periarterial sympathetic nerves. Next, kidneys were treated with either L-p-bromotetramisole (0.1 mmol/L), levamisole (1 mmol/L) or 2,5-dimethoxy-N-(quinolin-3-yl)benzenesulfonamide (0.02 mmol/L) and a frequency-response relationship (2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 Hz) was generated. With each TNAP inhibitor a group of control kidneys not receiving any treatment was included (i.e., 3 groups of control kidneys). Because the three groups of control kidneys responded similarly, for statistical purposes we combined these into one control group of n=18. As shown in Figure 6, L-p-bromotetramisole (Figure 6A), levamisole (Figure 6B) and 2,5-dimethoxy-N-(quinolin-3-yl)benzenesulfonamide (Figure 6C) significantly (P<0.0001, P<0.006 and P<0.0001, respectively) suppressed the RSNS-induced frequency-response relationship. Importantly, with all 3 inhibitors the suppression of RSNS-induced renovascular responses did not occur at low frequencies of stimulation, but only when frequencies were greater than 4 Hz.

Figure 6. Effects of TNAP inhibitors on renovascular responses to renal sympathetic nerve stimulation.

Line graphs depict renovascular responses to renal sympathetic nerve stimulation (RSNS) in the absence and presence of L-p-bromotetramisole (0.1 mmol/L; Panel A), levamisole (1 mmol/L; Panel B) and 2,5-dimethoxy-N-(quinolin-3-yl)benzenesulfonamide (0.02 mmol/L; Panel C). Data were analyzed by repeated measures 2-factor ANOVA. aSignificant difference (P<0.05; Fisher’s LSD test) within a group between indicated frequency of RSNS versus lowest frequency of RSNS. bSignificant difference (P<0.05; Fisher’s LSD test) between groups at indicated frequency of RSNS. Values are means and SEMs.

Protocol 6

To exclude any potential cofounding effect of changes in phosphate concentrations in the perfusate, we measured renal venous phosphate levels before and during administration of L-p-bromotetramisole (0.1 mmol/L). As shown in Figure S1, L-p-bromotetramisole did not alter renal venous perfusate levels of phosphate.

Protocol 7

To determine whether NE regulates the release of TNAP, TNAP activity was measured in renal venous perfusate collected before and after treatment with NE (0.5 μmol/L for 5 minutes). This experiment was performed in both naïve kidneys and kidneys pretreated with CCPA (0.1 μmol/L beginning 10 minutes before administering NE). As shown in Figure S2, treatment with NE did not release TNAP activity from naïve rat kidneys; yet in kidneys pretreated with CCPA, NE caused a 7-fold increase in the release of TNAP activity (P<0.03). CCPA per se had no effect on the release of TNAP activity. In preliminary experiments we observed that RSNS (7 Hz) did not release TNAP activity either in the absence or presence of CCPA (data not shown).

Protocol 8

To determine whether TNAP inhibition attenuates NE-induced renal vasoconstriction in vivo, anesthetized rats were administered NE while monitoring MABP and RBF. Rats were pretreated with the β-blocker propranolol to prevent NE-induced activation of β-adrenoceptors. This allowed an assessment of the effects of NE via α-adrenoceptors on MABP and RBF without confounding by NE-induced renin release and tachycardia. Some rats were pretreated with L-p-bromotetramisole (30 mg/kg delivered intravenously as two slow boluses) and others were pretreated with the vehicle for L-p-bromotetramisole (i.e., saline). Figure S3 demonstrates that the increases in MABP and renal vascular resistance (RVR = MABP/RBF) induced by NE were significantly (P<0.002 and P<0.02, respectively) inhibited by L-p-bromotetramisole.

Protocol 9

To examine whether cell types within the renal microcirculation express TNAP, PGVSMCs and PGVECs were isolated and placed in cell culture, and cell protein extracts were obtained for determination of TNAP expression by western blotting. As shown in Figure S4, both PGVSMCs and PGVECs expressed TNAP.

DISCUSSION

Our previous published studies show that in the renal vasculature, the Gi signaling pathway (which A1 receptors engage) converges with the Gq signaling pathway (which α1-adrenoceptors engage) to trigger “coincident signaling” at phospholipase C leading to augmentation by adenosine of renovascular responses to NE1. This explains why activation of A1 receptors by endogenous adenosine affords full renovascular response to RSNS1, 2. However, this concept is at odds with our findings that neither inhibition of CD39 nor CD73 (i.e., the most important set of enzymes for producing extracellular adenosine from ATP17–20) affect renovascular responses to RSNS21.

To reconcile the fact that A1 receptors are required to achieve a full renovascular response to RSNS with the fact that blocking CD39 or CD73 does not affect renal sympathetic neurotransmission, we hypothesized that the pool of adenosine that modulates renovascular responses to NE is produced by an alternative biochemical pathway. Because 1) TNAP mRNA, protein and activity are present in kidneys24, 2) TNAP can metabolize ATP to adenosine23, and 3) TNAP contributes to the metabolism of 5′-AMP to adenosine in kidneys24, we further hypothesized that TNAP mediates in part the alternative adenosine-producing pathway regulating renovascular responses to RSNS.

In this study, we observed that in isolated, perfused rat kidneys administration of TNAP inhibitors right-shifted the concentration-response relationship to exogenous NE by approximately 10-fold. Moreover, we found that the attenuation of renovascular responses to NE by TNAP inhibition was partially prevented or reversed by administration of the highly selective A1 receptor agonist, CCPA. That is to say, by restoring A1 receptor activation, the effects of TNAP inhibition were attenuated. These results are consistent with the concept that TNAP inhibition decreases the pool of adenosine that modulates renovascular responses to exogenous NE such that restoration or maintenance of adenosinergic tone partially rescues or prevents suppression of the NE response by TNAP inhibition. Indeed, measurement of renal venous levels of 5′-AMP (adenosine precursor) and adenosine per se showed that TNAP inhibition decreased the renal biosynthesis of adenosine. The present results, taken together with our previous findings that adenosine via the A1 receptor engages convergent signaling with NE at the level of phospholipase C, provides evidence supporting the conclusion that TNAP modulates renovascular responses to NE in part by maintaining a pool of adenosine that modulates the renovascular response to NE.

An important question is whether the ability of TNAP inhibition to attenuate the renovascular response to NE translates into attenuation of renovascular responses to NE released from sympathetic nerve varicosities. In the present investigation, we observed that all 3 TNAP inhibitors attenuated renovascular responses to all concentrations of NE. In contrast, although all 3 TNAP inhibitors attenuated renovascular responses to RSNS, this effect was observed only at frequencies greater than 4 Hz. This unanticipated finding requires explanation.

Studies by Sedaa et al.33 show that the vascular endothelium is the primary source of adenine nucleotides (including adenosine) in blood vessels, and the western blot experiments in the present study demonstrate that PGVECs indeed express TNAP. Also the combination of A1-receptor activation (in the present study with CCPA) plus α-adrenoceptor stimulation with luminal (exogenous) NE causes release of TNAP activity into the renovascular circulation. Release of TNAP into the vascular lumen could amplify the luminal production of adenosine which could further augment the vascular effects of luminal NE. Thus it would be expected that vascular smooth muscle cells positioned near the luminal side of the blood vessels would be constantly under the influence of endothelium-derived adenosine. Because administration of exogenous NE activates vascular smooth muscle cells underneath and adjacent to vascular endothelial cells, this may explain why TNAP inhibition attenuates renovascular responses to even low concentrations of NE.

Unlike exogenous NE, NE released from sympathetic nerve terminals activates abluminal (i.e., adventitial) vascular smooth muscle cells that are most likely under the influence of adenine nucleotides co-released from sympathetic varicosities. In this regard, measurable release of adenine nucleotides by sympathetic nerve stimulation seems to occur only at high frequencies of nerve stimulation. For example, Vonend et al. studied adenine nucleotide release from human kidney slices using field stimulation of 20 Hz34, Ishii et al.35 investigated adenine nucleotide release from rabbit ear, femoral, renal and pulmonary arteries using 16 Hz stimulation, and Goncalves et al. used 7 Hz stimulation to examine adenine nucleotide release from guinea-pig isolated vas deferens36. We previously measured adenosine release from isolated, perfused rat kidneys and found that release of adenosine was difficult to detect at frequencies of nerve stimulation less than 5 Hz3. Also, in the present study we did not observe an interaction between A1-receptor activation with CCPA and abluminal (endogenous) NE with respect to the release of TNAP activity. It is likely then that the lack of effect of TNAP inhibition on responses to RSNS at low frequencies is related to the inadequate release of ATP and relatively low formation rate of adenosine at the abluminal aspect of renal blood vessels.

At present we do not know how A1-receptor activation allows luminal NE to release TNAP into the renal circulation; but we do have a working hypothesis. TNAP is a GPI-anchored ecto-enzyme22, and in the secretory pathway GPI-PLD cleaves the GPI anchor from TNAP37–41, and TNAP becomes a secreted, soluble enzyme. GPI-PLD activity is inhibited by protein kinase A (PKA)-mediated phosphorylation of threonine 28642. Because A1 receptors are negatively coupled to adenylyl cyclase43, A1-receptor activation would lower cAMP, turn off PKA, reduce phosphorylation of GPI-PLD, increase GPI-PLD activity and thus increase the formation of soluble (releasable) TNAP in vascular endothelial cells. Also, PKC is activated by A1 receptor/α1-adrenoceptor coincident signaling1 and PKC accelerates the secretory pathway44. Therefore we tentatively hypothesize that co-activation of A1 receptors and α1-adrenoceptors in the vascular endothelium may increase the release of soluble TNAP by these mechanisms.

Because isolated, perfused kidneys are not in their natural environment, it is possible that TNAP inhibition reduces renovascular responses to NE in isolated kidneys, but not in kidneys in vivo. In the present study we tested this by infusing NE intravenously into rats treated or not with L-p-bromotetramisole. This experiment was conducted in rats pretreated with propranolol to block the ability of NE to affect MABP and RVR by activating the renin-angiotensin system and/or by increasing heart rate and cardiac output. Under these conditions, L-p-bromotetramisole attenuated NE-induced changes in MABP and RVR. These findings provide affirmation that our results in vitro can be extrapolated to the in vivo condition.

The size of the effect of TNAP inhibitors on renovascular responses to NE and RSNS exceeded our expectations. Therefore, we are not confident that the observed effects are only due to a reduction in adenosine levels, and hypothesize that other yet-to-be-discovered mechanisms are involved that may or may not entail TNAP inhibition. However, some potential mechanisms can be excluded. For example, although it is conceivable that TNAP inhibitors cause direct α-adrenoceptor blockade, published studies are inconsistent with this hypothesis. Gulati et al. reported that in the guinea pig vas deferens levamisole actually enhanced responses to exogenous NE and field stimulation and concluded that levamisole does not block α-adrenoceptors but rather inhibits NE uptake45. Joshi and Verma observed that levamisole caused contractions of the rat anococcygeus muscle that are blocked by phentolamine and concluded that levamisole is an agonist (not antagonist) of α-adrenoceptors46. Vanhoutte et al. 47 and Van Nueten48 did not observe α-adrenoceptor blocking activity of levamisole in dog saphenous veins and rabbit spleens, respectively.

Nothing is known regarding the local anesthetic actions of L-p-bromotetramisole or 2,5-dimethoxy-N-(quinolin-3-yl)benzenesulfonamide. However, Onuaguluchi and Igbo reported that levamisole caused surface anesthesia in the rabbit cornea with an EC50 of approximately 300 mmol/L and infiltration local anesthesia in the guinea pig intradermal model with an EC50 of approximately 0.8 mmol/L49. Obviously local anesthetics do not block α-adrenoceptor-induced vasoconstriction because epinephrine is commonly co-administered with lidocaine to cause vasoconstriction and limit the local absorption of lidocaine into the systemic circulation. Indeed the local anesthetic dibucaine does not inhibit vasoconstriction by exogenous NE in the rat mesentery50. Therefore any local anesthetic action could not explain the ability of TNAP inhibitors to reduce the responsiveness of the renal vasculature to exogenous NE. Although a membrane stabilizing effect of TNAP inhibitors could partially explain the effects of these agents on responses to RSNS, one would anticipate inhibition of responses to RSNS at all frequencies rather than just at frequencies > 4 Hz. For example, dibucaine inhibits noradrenergic neurotransmission in the rat mesentery at 3 Hz nerve stimulation50. Nonetheless, it remains conceivable that a local anesthetic action explains in part the effects of TNAP inhibitors on RSNS responses but not exogenous NE.

Another potential mechanism is that somehow changes in phosphate levels alter renovascular responsiveness to NE. However, we could not detect changes in phosphate levels exiting the renal vein. Additional studies, for example in TNAP knockout animals, are warranted to confirm that TNAP inhibitors attenuate renovascular responses to NE by reducing TNAP activity and to elucidate the full mechanistic details by which TNAP inhibitors attenuate NE-induced reductions in RVR. Also, it will be of interest to examine the effects of TNAP inhibitors on responses to NE in alternative vascular beds to determine whether the observed effects of TNAP inhibitors on renovascular responses to NE apply only to the kidneys or occur also in non-renal vascular beds.

Perspectives

The most important aspect of this research is that it identifies the ability of TNAP inhibitors to attenuate renovascular responses to both luminal and abluminal NE. This effect appears to be mediated at least partially by inhibition of adenosine production in the kidney that is normally maintained by TNAP activity. We also find that TNAP inhibitors attenuate the effects of NE on MABP and RVR in vivo suggesting a new modality of treating cardiovascular diseases and hypertension.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What Is New?

This study establishes that TNAP inhibitors attenuate renovascular responses to both exogenous and endogenous norepinephrine and reduce the pressor effects of NE.

This study also demonstrates that TNAP inhibitors reduce the production of adenosine by the kidneys and that likely this contributes, at least in part, to the attenuation by TNAP inhibitors of NE-induced renal vasoconstriction.

What Is Relevant?

TNAP inhibitors attenuate NE-induced renal vasoconstriction.

These studies identify a new mechanism for blocking the effects of catecholamines on the renal vasculature.

These studies also identify TNAP as a potential target for the treatment of hypertension and cardiovascular and renal diseases.

Summary

Here we report that 3 TNAP inhibitors attenuate renovascular responses to exogenous NE and endogenous NE released by renal sympathetic nerve stimulation. These findings corroborate the hypothesis that TNAP inhibition attenuates renovascular response to both luminal and abluminal norepinephrine and suggest the prospect that TNAP inhibition could attenuate the effects of the sympathoadrenal axis on renal function and blood pressure.

Acknowledgments

SOURCES OF FUNDING

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [DK091190, HL069846, DK068575, HL109002 and DK079307].

Footnotes

Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Jackson EK, Cheng D, Tofovic SP, Mi Z. Endogenous adenosine contributes to renal sympathetic neurotransmission via postjunctional A1 receptor-mediated coincident signaling. Am J Physiol Renal. 2012;302:F466–476. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00495.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackson EK, Cheng D, Mi Z, Verrier JD, Janesko-Feldman K, Kochanek PM. Role of A1 receptors in renal sympathetic neurotransmission in the mouse kidney. Am J Physiol Renal. 2012;303:F1000–1005. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00363.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mi Z, Jackson EK. Effects of α- and β-adrenoceptor blockade on purine secretion induced by sympathetic nerve stimulation in the rat kidney. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;288:295–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ren J, Mi ZC, Jackson EK. Assessment of nerve stimulation-induced release of purines from mouse kidneys by tandem mass spectrometry. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;325:920–926. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.137752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackson EK, Zhu C, Tofovic SP. Expression of adenosine receptors in the preglomerular microcirculation. Am J Physiol Renal. 2002;283:F41–51. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00232.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleming JT, Zhang C, Chen J, Porter JP. Selective preglomerular constriction to nerve stimulation in rat hydronephrotic kidneys. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:F348–353. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1992.262.3.F348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Westfall DP, Todorov LD, Mihaylova-Todorova ST. ATP as a cotransmitter in sympathetic nerves and its inactivation by releasable enzymes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;303:439–444. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.035113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lew MJ, White TD. Release of endogenous ATP during sympathetic-nerve stimulation. Br J Pharmacol. 1987;92:349–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1987.tb11330.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sneddon P, Burnstock G. Inhibition of excitatory junction potentials in guinea-pig vas-deferens by α,β-methylene-ATP - further evidence for ATP and noradrenaline as cotransmitters. Eur J Pharmacol. 1984;100:85–90. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(84)90318-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sneddon P, Burnstock G. ATP as a co-transmitter in rat tail artery. Eur J Pharmacol. 1984;106:149–152. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(84)90688-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Billaud M, Lohman AW, Straub AC, Looft-Wilson R, Johnstone SR, Araj CA, Best AK, Chekeni FB, Ravichandran KS, Penuela S, Laird DW, Isakson BE. Pannexin1 Regulates α1-Adrenergic Receptor–Mediated Vasoconstriction. Circ Res. 2011;109:80–85. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.237594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katsuragi T, Tokunaga T, Ogawa S, Soejima O, Sato C, Furukawa T. Existence of ATP-evoked ATP release system in smooth muscles. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991;259:513–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bodin P, Burnstock G. Synergistic effect of acute-hypoxia on flow-induced release of ATP from cultured endothelial-cells. Experientia. 1995;51:256–259. doi: 10.1007/BF01931108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bodin P, Bailey D, Burnstock G. Increased flow-induced ATP release from isolated vascular endothelial-cells but not smooth-muscle cells. Br J Pharmacol. 1991;103:1203–1205. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12324.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bodin P, Burnstock G. ATP-stimulated release of ATP by human endothelial cells. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1996;27:872–875. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199606000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faigle M, Seessle J, Zug S, El Kasmi KC, Eltzschig HK. ATP release from vascular endothelia occurs across Cx43 hemichannels and is attenuated during hypoxia. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:0002801. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eltzschig HK, Weissmuller T, Mager A, Eckle T. Nucleotide metabolism and cell-cell interactions. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;341:73–87. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-113-4:73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eltzschig HK, Kohler D, Eckle T, Kong T, Robson SC, Colgan SP. Central role of Sp1-regulated CD39 in hypoxia/ischemia protection. Blood. 2009;113:224–232. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-165746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eltzschig HK, Sitkovsky MV, Robson SC. Purinergic signaling during inflammation. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2322–2333. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1205750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eltzschig HK. Extracellular adenosine signaling in molecular medicine. J Mol Med. 2013;91:141–146. doi: 10.1007/s00109-013-0999-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson EK, Cheng D, Mi Z, Verrier JD, Janesko-Feldman K, Kochanek PM. Role of CD73 in renal sympathetic neurotransmission in the mouse kidney. Physio Rep. 2013;1:e00057. doi: 10.1002/phy2.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zimmermann H, Zebisch M, Strater N. Cellular function and molecular structure of ecto-nucleotidases. Purinergic Signal. 2012;8:437–502. doi: 10.1007/s11302-012-9309-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaulich M, Qurishi R, Muller CE. Extracellular metabolism of nucleotides in neuroblastoma x glioma NG108–15 cells determined by capillary electrophoresis. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2003;23:349–364. doi: 10.1023/A:1023640721630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson EK, Cheng D, Verrier JD, Janesko-Feldman K, Kochanek PM. Interactive roles of CD73 and tissue nonspecific alkaline phosphatase in the renal vascular metabolism of 5′-AMP. Am J Physiol Renal. 2014;307:F680–F685. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00312.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jackson EK, Menshikova EV, Mi Z, Verrier JD, Bansal R, Janesko-Feldman K, Jackson TC, Kochanek PM. Renal 2′,3′-Cyclic Nucleotide 3′-Phosphodiesterase Is an Important Determinant of AKI Severity after Ischemia-Reperfusion. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:2069–2081. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015040397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borgers M. The cytochemical application of new potent inhibitors of alkaline phosphatases. J Histochem Cytochem. 1973;21:812–824. doi: 10.1177/21.9.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borgers M, Thone F. The inhibition of alkaline phosphatase by L-p-bromotetramisole. Histochemistry. 1975;44:277–280. doi: 10.1007/BF00491496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dahl R, Sergienko EA, Su Y, Mostofi YS, Yang L, Simao AM, Narisawa S, Brown B, Mangravita-Novo A, Vicchiarelli M, Smith LH, O’Neill WC, Millan JL, Cosford NDP. Discovery and validation of a series of aryl sulfonamides as selective inhibitors of tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase (TNAP) J Med Chem. 2009;52:6919–6925. doi: 10.1021/jm900383s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacobson KA, Knutsen LJS. P1 and P2 purine and pyrimidine receptor ligands. In: Abbracchio MP, Williams M, editors. Purinergic and Pyrmidinergic Signalling I. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2001. pp. 129–175. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frye CA, Patrick CW., Jr Isolation and culture of rat microvascular endothelial cells. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 2002;38:208–212. doi: 10.1290/1071-2690(2002)038<0208:IACORM>2.0.CO;2. Animal. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mokkapatti R, Vyas SJ, Romero GG, Mi Z, Inoue T, Dubey RK, Gillespie DG, Stout AK, Jackson EK. Modulation by angiotensin II of isoproterenol-induced cAMP production in preglomerular microvascular smooth muscle cells from normotensive and genetically hypertensive rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;287:223–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verrier JD, Jackson TC, Gillespie DG, Janesko-Feldman K, Bansal R, Goebbels S, Nave K-A, Kochanek PM, Jackson EK. Role of CNPase in the oligodendrocytic extracellular 2′,3′-cAMP-adenosine pathway. GLIA. 2013;61:1595–1606. doi: 10.1002/glia.22523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sedaa KO, Bjur RA, Shinozuka K, Westfall DP. Nerve and drug-induced release of adenine nucleosides and nucleotides from rabbit aorta. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;252:1060–1067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vonend O, Oberhauser V, von Kugelgen I, Apel TW, Amann K, Ritz E, Rump LC. ATP release in human kidney cortex and its mitogenic effects in visceral glomerular epithelial cells. Kidney Int. 2002;61:1617–1626. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ishii R, Shinozuka K, Kunitomo M, Hashimoto T, Takeuchi K. Regional differences of endogenous ATP release in rabbit arteries. Comp Biochem Physiol C Pharmacol Toxicol Endocrinol. 1996;113:387–391. doi: 10.1016/0742-8413(96)00006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goncalves J, Driessen B, von Kugelgen I, Starke K. Comparison of corelease of noradrenaline and ATP evoked by hypogastric nerve stimulation and field stimulation in guinea-pig vas deferens. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1995;352:229–235. doi: 10.1007/BF00176779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mann KJ, Hepworth MR, Raikwar NS, Deeg MA, Sevlever D. Effect of glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-phospholipase D overexpression on GPI metabolism. Biochem J. 378:641–648. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moon YG, Lee HJ, Kim MR, Myung PK, Park SY, Sok DE. Conversion of glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored alkaline phosphatase by GPI-PLD. Arch Pharm Res. 22:249–254. doi: 10.1007/BF02976358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Solter PF, Hoffmann WE. Solubilization of liver alkaline phosphatase isoenzyme during cholestasis in dogs. Am J Vet Res. 60:1010–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsujioka H, Takami N, Misumi Y, Ikehara Y. Intracellular cleavage of glycosylphosphatidylinositol by phospholipase D induces activation of protein kinase Calpha. Biochem J. 342:449–455. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoshida M, Sakuragi N, Kondo K, Tanesaka E. Cleavage with phospholipase of the lipid anchor in the cell adhesion molecule, csA, from Dictyostelium discoideum. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 143:138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Civenni G, Butikofer P, Stadelmann B, Brodbeck U. In vitro phosphorylation of purified glycosylphosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase D. Biol Chem. 1999;380:585–588. doi: 10.1515/BC.1999.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fredholm BB, Ijzerman AP, Jacobson KA, Linden J, Muller CE International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXI. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors--an update. Pharmacol Rev. 2011;63:1–34. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsujioka H, Takami N, Misumi Y, Ikehara Y. Intracellular cleavage of glycosylphosphatidylinositol by phospholipase D induces activation of protein kinase Calpha. Biochem J. 1999;342:449–455. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gulati OD, Hemavathi KG, Joshi DP. Interactions of levamisole with some autonomic drugs on guinea-pig vas deferens. J Auton Pharmacol. 1985;5:19–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-8673.1985.tb00561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Joshi DP, Verma SC. Studies on autonomic actions of levamisole and phenylephrine in rat anococcygeus and frog’s isolated heart. Ind J Pharmacol. 1982;14:313–318. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vanhoutte PM, Van Nueten JM, Verbeuren TJ, Laduron PM. Differential effects of the isomers of tetramisole on adrenergic neurotransmission in cutaneous veins of dog. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1977;200:127–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Nueten JM. Pharmacological aspects of tetramisole. In: Bossche HVd., editor. Comparative Biochemistry of Parasites. Elsevier; 1972. pp. 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Onuaguluchi G, Igbo IN. Comparative local anaesthetic and antiarrhythmic actions of levamisole hydrochloride and lignocaine hydrochloride. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1987;289:278–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jackson EK, Campbell WB. A possible antihypertensive mechanism of propranolol: antagonism of angiotensin II enhancement of sympathetic nerve transmission through prostaglandins. Hypertension. 1981;3:23–33. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.3.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.