Energized by a vertical alternating magnetic field, colloidal particles roll and flock together.

Keywords: self-assembly, colloids, active matter, flocking, Collective Behavior, Synchronization

Abstract

Assemblages of microscopic colloidal particles exhibit fascinating collective motion when energized by electric or magnetic fields. The behaviors range from coherent vortical motion to phase separation and dynamic self-assembly. Although colloidal systems are relatively simple, understanding their collective response, especially under out-of-equilibrium conditions, remains elusive. We report on the emergence of flocking and global rotation in the system of rolling ferromagnetic microparticles energized by a vertical alternating magnetic field. By combing experiments and discrete particle simulations, we have identified primary physical mechanisms, leading to the emergence of large-scale collective motion: spontaneous symmetry breaking of the clockwise/counterclockwise particle rotation, collisional alignment of particle velocities, and random particle reorientations due to shape imperfections. We have also shown that hydrodynamic interactions between the particles do not have a qualitative effect on the collective dynamics. Our findings shed light on the onset of spatial and temporal coherence in a large class of active systems, both synthetic (colloids, swarms of robots, and biopolymers) and living (suspensions of bacteria, cell colonies, and bird flocks).

INTRODUCTION

Colloids, that is, suspensions of microscopic particles, play an important role in everyday life and are crucial for many industries, from pharmaceutical to medicine and nanotechnology. A multitude of forces govern their behavior, from steric repulsion, electrostatic, magnetic, and van der Waals forces to gravity, hydrodynamics, etc. (1). Despite their seeming simplicity, colloidal systems may exhibit fascinating collective behavior when they are driven out of equilibrium by external magnetic or electric fields (2). Recent studies have led to the discovery of self-assembled swimmers, microrobots, and spinners in the system of driven ferromagnetic colloids (3–5), self-assembly of dynamic rings and vortices in electrostatically driven metallic particles (6), reconfigurable active patterns in metal-dielectric Janus colloids (7), formation of complex vorticity patterns of paramagnetic colloids in triaxial alternating fields (8, 9), emergence of large vortices in the system of colloidal dielectric rollers energized by an electric field (10, 11), ionic crystals and lane formation in bidisperse colloidal suspensions (12), crystal formation of light-induced colloidal surfers (13), and many others.

Studies of driven colloids have highlighted a close relation to a broad class of systems termed active matter: assemblies of self-propelled particles capable of transducing energy stored in the environment into mechanical motion. Active matter has a strong propensity toward the onset of large-scale collective behavior stemming from a simple alignment interaction between the self-propelled agents. In living systems, this collective behavior is exemplified by bacterial swarms, bird flocks, fish schools, etc. (14). Many aspects of collective behavior, at least on a qualitative level, are captured by a paradigmatic Vicsek model for the interacting self-propelled point particles (15). Although significant progress has been made in the theoretical understanding of model active systems [for example, see recent research (16–18)] in many experimental realizations of active matter (19–24), a multitude of long-range interactions (for example, hydrodynamic, magnetic, electrostatic, elastic, etc.) often obscure and complicate the simple phenomenology exhibited by the Vicsek model.

The emergence of large vortices and propagating densification fronts (so-called Vicsek bands) has been reported in the system of rolling colloids energized by the dc electric field (10, 11). Self-propulsion is an outcome of the spontaneous rotation of a dielectric sphere in a conducting fluid when it is exposed to a dc electric field [Quincke effect (25)]. Although many experimental findings from the study of Bricard et al. (10, 11) were successfully reproduced by coarse-grained continuum theory and simplified particle dynamics model, individual interactions between the particles are hard to quantify, especially the effects of the dielectric polarization and hydrodynamic forces.

Here, we report on the discovery of ferromagnetic flocking colloids. The experimental system is realized by ferromagnetic colloidal spheres energized by a vertical alternating (ac) magnetic field. Particles are settled on a slightly concave bottom surface of a liquid-filled container (see Materials and Methods). The rolling motion appears due to a spontaneous symmetry breaking of the clockwise/counterclockwise rotation experienced by a magnetic sphere in a uniaxial field (5). Depending on the frequency of the external magnetic field, a sequence of transitions can be observed: from gas-like motion of individual particles at low frequencies to the onset of flocking and global rotation, followed by a reentrant flocking and gas-like state for increasing frequency. Like in living systems, flocking behavior is characterized by a spontaneous onset of coherently moving groups of many particles. However, the flocks do not keep their identity; they often change their direction, break up, and reassemble. Our discrete particle simulations have provided insight into the behavior of our experimental system. We have established that the flocking is an outcome of mostly collisional and magnetic interactions between the particles, whereas the long-range hydrodynamic forces do not have a qualitative effect on the collective behavior. We have also observed a strong correlation between the onset of flocking and the synchronization of particle motion by the applied ac magnetic field. Our work provides fundamental insights into a broad class of active systems, both synthetic and living, where collective motion is caused by a subtle interplay of long- and short-range interactions. Control and prediction of collective behavior in out-of-equilibrium colloidal systems also lead to a better understanding of fundamental aspects of dynamic self-assembly in general and novel properties of functional colloidal materials.

RESULTS

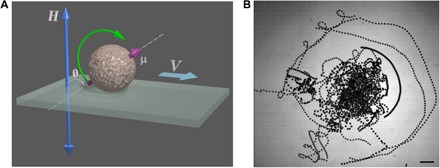

In our experiment, a dispersion of ferromagnetic nickel spheres was deposited on the bottom of a liquid-filled container. The bottom surface of the container was formed by a concave glass lens. The lens was used to drive the particles toward the center and to prevent them from accumulating at the container walls. A uniform vertical alternating magnetic field was used to energize the particles (see Materials and Methods for details). Typically, up to 400 particles were used in each experiment. The schematics of our experiment are shown in Fig. 1A.

Fig. 1. Schematics of the experiment and particle trajectories.

(A) Schematics of the experiment. A nonsmooth ferromagnetic particle with the magnetic moment μ is energized by an applied vertical ac magnetic field. Particle rotation leads to a self-propelled motion with the velocity V. (B) Trajectories of 25 particles observed over 100 periods of the ac magnetic field. Some particles escape the center of the lens, whereas other particles remain near the center of the lens most of the time. Scale bar, 1 mm.

The main experimental results are summarized in Figs. 1 to 4. Figure 1B illustrates the trajectories of individual particles. Whereas some particles roll persistently, other particles may stop and exhibit almost no rolling for extended periods of time. This variability in particle behaviors is likely due to the dispersion of the particle sizes and, correspondingly, magnetic moments as well as shapes and roughness. A sequence of experimentally observed transitions is illustrated in Fig. 2. The transitions between the states are quantified by the corresponding order parameter for in-plane rotational collective motion, φR, defined as (26)

| (1) |

where are the in-plane unit vectors in angular direction, vi are the in-plane unit velocities of the individual particles, and N is the total number of particles. The order parameter attains its maximal values ±1 for pure rotation. Time evolution of the order parameters for the different regimes after reaching a steady state is shown in Fig. 3B.

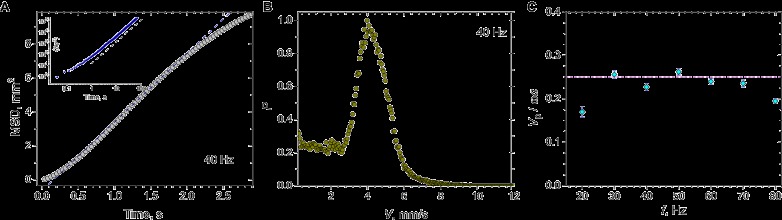

Fig. 4. Individual particle dynamics.

(A) Mean square displacement (MSD) of individual particles at frequency f = 40 Hz and magnetic field magnitude H0 = 70 Oe; the dashed line is a linear law. For longer times, the curve saturates due to finite system size. Inset: Angular mean square displacement (〈δϕ2〉) for the same experimental conditions. (B) Particle velocity distribution function; the average is taken over 4 × 104 instantaneous velocity values of individual rollers at f = 40 Hz. (C) Typical particle velocity normalized by maximally attained velocity V0 = ωa, with ω = 2πf. The dashed line indicates the value of the slipping parameter αs used in simulations.

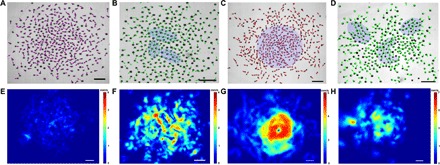

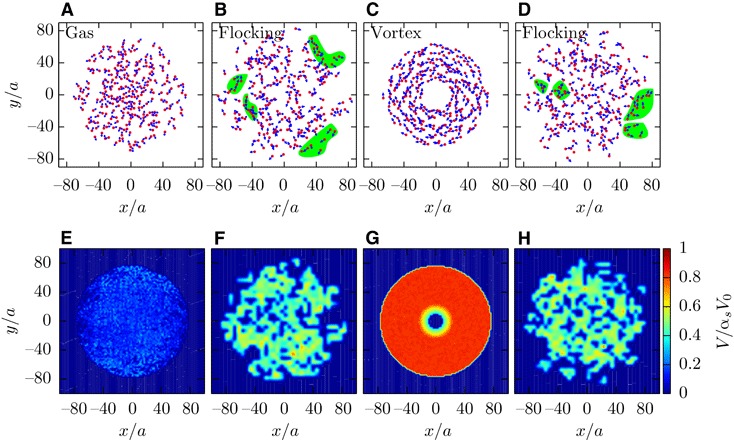

Fig. 2. Main observed phases.

(A to D) Snapshots of the individual particle velocities for the four major phases: gas (f = 20 Hz) (A), flocking (f = 30 Hz) (B), vortex (f = 40 Hz) (C), and reentrant flocking (f = 50 Hz) (D) (see also movies S1 to S8). Individual flocks in (B) and (D) are accented by light colors. (E to H) Magnitude of the corresponding coarse-grained velocity fields. Scale bars, 1 mm.

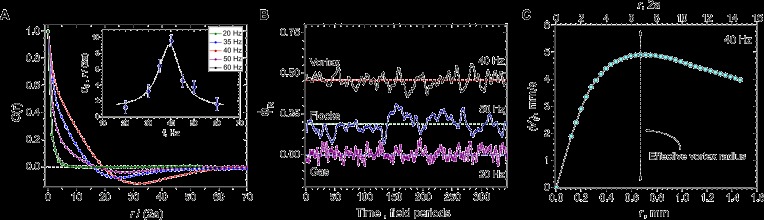

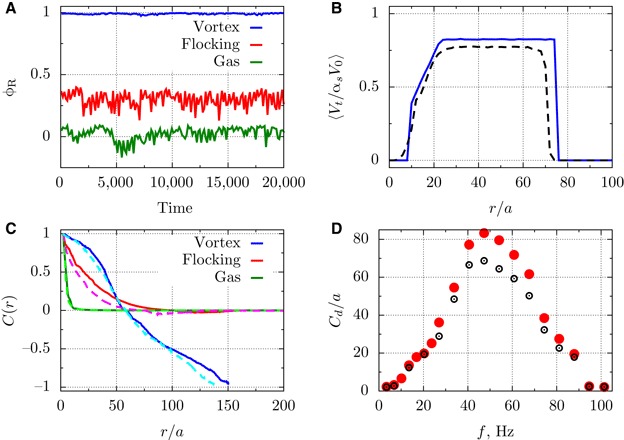

Fig. 3. Collective particle dynamics.

(A) Spatial particle velocity correlation functions for different frequencies; here, a is the particle radius. Inset: Correlation length versus frequency f. When the correlation length becomes comparable to the system size for the frequency f ≈ 40 Hz, the particle motion is self-organized into a large vortex. The dashed line serves as a guide to the eyes. (B) Rotational order parameter φR for gas, flocking, and vortex states. (C) Vortex velocity profile versus distance from the center.

The experimental transitions can be summarized as follows: For low frequencies f < 30 Hz, a gas-like state of randomly moving particles was observed (see Fig. 2, A and E, and movie S1). While individual particles roll, the order parameter for rotational collective motion ϕR was close to 0 (see Fig. 3B), and their individual velocities seem uncorrelated (see Fig. 3A). Correspondingly, for this state, the time-averaged rotational velocity is close to 0 (see Fig. 2E).

Increase in the frequency of the magnetic field resulted in a markedly new phenomenon: the onset of a behavior, which is reminiscent of bird flocks and fish schools, where large groups of particles start to move coherently and form well-defined flocks. These flocks are not static: they break up and reassemble in different locations (see Fig. 2, B and F, and movies S2 and S3). Correspondingly, the order parameter ϕR fluctuates over time at around a value of 0.2.

Further increase in the field frequency results in the increase in size and persistence time of the flocks. It eventually leads to the emergence of a vortex spanning the entire system and continuously rotating in a certain direction (see Fig. 2, C and G, and movies S4 and S5). The order parameter attains a maximal value at about 0.5 and shows fluctuations around the mean value (Fig. 3B). The sense of rotation is determined by an initial particle configuration and changes from experiment to experiment. The core of the vortex is characterized by an almost linear azimuthal velocity profile (Fig. 3C). Further increase in the frequency results in the breakdown of the coherent vortex motion and formation of a reentrant flocking state (see Fig. 2, D and H, and movies S6 and S7) and, finally, a gas-like state (see movie S8).

Figure 3A displays the spatial correlation functions for different values of the driving frequency f. Correlation length provides valuable information on the changes in the system order; however, the absolute value of it depends on the particle number density. As anticipated, the correlation length is minimal in the gas phase (f = 20 Hz). Then, the correlation length increases with the frequency and attains a value of 15 to 20 particle sizes in the flocking state (f = 35 Hz). It becomes comparable with the system size in the vortex state (f = 40 Hz). Moreover, the negative values in the correlation function indicate a large-scale rotational motion leading to anticorrelations. Then, with further increase in f, the correlation length decreases again. The inset in Fig. 3A shows that the correlation length peaks at the frequency f ≈ 39 Hz. In this case, the correlation length is possibly limited by the system size.

DISCUSSION

Individual particle dynamics

To obtain insights into the onset of collective behavior, we first investigated the dynamics of individual particles for very low concentrations (25 to 40 particles). The results are summarized in Fig. 4. Although individual particles roll and exhibit self-propelled motion, the trajectories resemble a random walk due to shape imperfections. The averaged mean square displacements of individual particles at a 40-Hz excitation frequency are shown in Fig. 4A. The behavior is consistent with the linear law characterized by translation diffusion coefficient DT. For f = 40 Hz, we obtained DT ≈ 1 mm2 s–1. From the measurements of the translation diffusion, we infer the effective rotational diffusion coefficient DR using the well-known relation for the self-propelled particles

| (2) |

where V is the typical particle velocity (27). The estimate yields the following value for the rotational diffusion DR ≈ 3 to 4 s–1, with a corresponding persistent length l = V/DR ≈ 1 mm. We also estimated the rotational diffusion directly from the variance 〈δϕ2〉 of in-plane particle velocity orientation angle φ(t), with δϕ = ϕ(t) − ϕ(0). This variance behaves as 〈δϕ2〉 ≈ 2DRt for time t ≫ 1 s (see inset in Fig. 4A). Using this procedure, we obtained DR ≃ 3.5 s–1 for the excitation frequency f = 40 Hz. As the frequency of the excitation field increases, the rotational diffusion coefficient systematically decreases; however, variation of the magnetic field amplitude has not produced significant changes in the rotational diffusion coefficient.

Figure 4B shows the particle velocity distribution function P(V). The distribution is peaked at around a value of Vp ≈ 4 mm s–1, which depends on the frequency itself. There is a significant population of particles that almost does not roll (likely due to lower values of the magnetic moment). This population is manifested by a plateau near V = 0.

Because of the contact with the surface, a rotating particle will roll. In the limit of no-slip contact with the surface, the rolling speed V0 would be V0 = ωa, where ω = 2πf. However, we have found from our experiments that this theoretical speed value is not attainable (see Fig. 4C). The particle rolling speeds are distributed around mean value , which is of the order in the range of our frequencies. Two main factors may contribute to the speed reduction. First, the fluid may work as a lubricant, leading to partial slip between the particle and the bottom. Second, a moving rotating particle near a solid surface will experience a lift force FL, which is of the order of the gravity for our conditions. In the Stokes limit, the lift force on a rotating sphere is FL = πρfa3ωV, where ρf is the fluid density, and V is the particle translation velocity (28). A particle loses contact with the substrate when the lift force FL becomes comparable with the gravity force Fg = mg = 4/3πρpa3, where m is the particle mass, ρp is the particle density, and g is the gravity. By using V = V0 = ωa, we obtain the lift-off condition . For nickel particles (ρp/ρf ≈ 9) with the radius a ≈ 60 to 100 μm, we find that the lift force will exceed gravity for frequencies in the range of f ≈ 60 to 100 Hz. This implies that the particle cannot be in a protracted contact with the surface above these frequencies. Correspondingly, it should move parallel to the surface with a speed smaller than V0.

The onset of rolling

The onset of rolling is associated with the spontaneous symmetry breaking of the clockwise/counterclockwise rotation of an individual particle in an ac vertical magnetic field. Non-negligible particle inertia is a main cause of the directed rotation (5). By neglecting fluctuations, the evolution of the particle angle θ with respect to vertical direction (see Fig. 1A) as a function of time in a vertical uniaxial ac magnetic field Hz = H0 sin(ωt) is described by the following equation of motion

| (3) |

where H0 is the magnitude of the applied field, ω = 2πf, μ is the magnetic moment of the particle, and I = 2/5ma2, and αr = 8πηa3 are the moment of inertia and the rotational drag coefficient, respectively (a is the particle radius, m is the particle mass, and η is the fluid dynamic viscosity). If the particle inertia is negligible compared to the viscous forces, the first term in Eq. 3 can be dropped, and it is reduced to

| (4) |

This equation can be solved exactly, leading to the family of periodic solutions

| (5) |

with ζ = μH0/αrω and an integration constant C0 determined by the initial conditions. Thus, these solutions would correspond to oscillations around some mean value of the angle θ. Any nonzero particle mass would lead to the breakdown of the family and locking of the angle to the values of either θ = 0 or θ = π. The effect of a small inertia can be demonstrated analytically by perturbing the solution given by Eq. 5. It is practical to consider the ε = I/αr ≪ 1 limit. For simplicity, we set in Eq. 5 C0 ≪ 1, leading to θ = C0 exp(ζcos(ωt)). For small ε, we use the solution in the form θ = C0(εt)exp(ζcos(ωt)). Plugging this into Eq. 3, in the first order in ε, we find, after a simple algebra, that C0 ~ exp(−λt), where . Thus, the particle will align in a vertical direction with the rate ~I for any small particle inertia.

However, the steady states θ = 0, π may become unstable with the increase of the particle inertia and/or field magnitude. This can be seen by linearizing Eq. 3 around θ = 0, π. Linearizing Eq. 3 after a proper scaling assumes the form

| (6) |

where are the normalized friction and field magnitude, respectively, and . Equation 6 can be reduced to the Mathieu equation whose solutions are well studied and tabulated (29). Correspondingly, Eq. 6 can be solved in terms of the Mathieu special functions (29). The time behavior of the Mathieu functions is determined by the Mathieu characteristic exponent v, which is the function of the parameters p and q. Thus, by transforming Eq. 5 to a canonical Mathieu form, one derives a condition for the instability of the steady states θ = 0, π

| (7) |

The condition provides a critical value of the friction coefficient when locking with the field direction becomes unstable. In the limit of small inertia I, (that is, p = αr/ωI ≫ 1), one finds from Eq. 7 that Λ < 0, consistent with our asymptotic analysis above. Thus, the locked states are stable. The threshold value of the normalized field q versus friction p obtained from the condition Λ = 0 is shown in Fig. 5A. One sees that the critical field value increases with the increase of the friction coefficient p. However, even for p → 0, there is a critical value of the field q ≈ 0.454 needed for instability of the locked state.

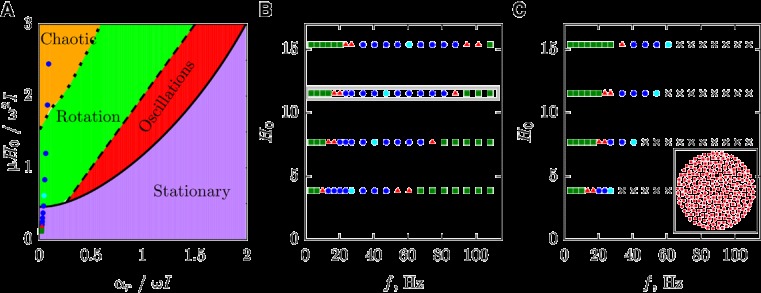

Fig. 5. Diagrams of the dynamic states.

(A) Individual particle dynamic states in the absence of noise. Solid line shows the stability limit of the locked state (Eq. 7). Below the solid line, the particle is oriented along the field direction. The thin dashed line depicts the rotating state existence boundary from the condition μH0 = 2αrω. Chaotic regimes, characterized by spontaneous reversal of the rotation direction, exist above the black diamond line. The symbols show the locations of gas, flocking, and vortex states. (B) Diagram of the dynamic states spanning the magnitude H0 and the frequency f of the alternating external field obtained from numerical simulations for rotational diffusion DR = 1 s–1. Squares correspond to gas, triangles correspond to flocking, and circles correspond to vortex. The vortex state with maximal correlation length is shown in light blue circles. Data points inside the gray rectangle are also shown in (A). (C) Diagram of the dynamic states for the parameters of (B) but without noise (DR = 0). Flocking and gas phases for higher frequencies are replaced by a stationary crystal-like phase (× symbols). Inset: Stationary crystal phase observed for high frequencies without noise.

Furthermore, by decomposing the driving term into two counterrotating waves and neglecting one of the terms in this expression (for example, the second), we obtain a damped pendulum equation

| (8) |

After making a transformation to a corotating frame, ψ = θ − ωt, one obtains an equation without explicit time dependence

| (9) |

The rotating state corresponds to a fixed point of Eq. 9. The corresponding fixed points exist for μH0 > 2αrω (or q = 2p), that is, for relatively small friction. Thus, Eq. 3 describes the rotation of the particle in clockwise direction with the frequency ω as long as q > 2p. A similar consideration is valid for the opposite direction of rotation. The direction of rotation is determined by the initial conditions and may change due to interactions with other particles. The rotating state existence boundary obtained from the condition q = 2p is shown in Fig. 5A by a thin dashed line.

Moreover, even a single particle may exhibit stochastic switching of its rotation direction if the field magnitude H0 becomes large enough. The approximate boundary for the chaotic regimes for very small friction αr → 0 is given by the resonance overlap criterion (30), which is q* = μH0/ω2I ⪆ 1/2 in our notation. However, this condition for q* underestimates the numerically obtained transition values somewhat by a factor of 3 (see Fig. 5A). For increased values of the friction coefficient αr, stronger magnetic fields are required for the onset of these chaotic regimes. The existence boundary of chaotic regimes, obtained by numerical solution of Eq. 3, is shown in Fig. 5A by black diamonds.

Although our system of ferromagnetic rollers appears seemingly related to the Quincke colloidal rollers energized by the dc electric field (10, 11), we want to emphasize a fundamental difference. The propulsion speed of the Quincke colloidal rollers depends on the magnitude of the electric field and vanishes at a critical field value. In contrast, for the ferromagnetic rollers energized by the ac magnetic field, the rotation speed does not depend on the field magnitude H0 and depends only on the field frequency f. Moreover, even individual ferromagnetic rollers exhibit complex dynamics characterized by spontaneous direction reversals. This particle behavior is not present in the electrostatic system of Quincke rollers. These intrinsic chaotic dynamics lead to the complexity of the phase diagram for ferromagnetic rollers.

Even in the absence of noise, the analysis of individual particle dynamics for ferromagnetic rollers provides nontrivial insight into the collective behavior of many interacting particles. We show below (see Fig. 5) that the transitions between different collective states are closely related to the boundaries in the phase diagram for individual particle (Fig. 5A).

Computational modeling of collective dynamics

To obtain insights into the onset of collective motion and to identify the most important particle interactions, we performed computational modeling of a colloidal system driven by a vertical magnetic field (see Materials and Methods for details). A phase diagram spanned by the amplitude and the frequency of the magnetic field is shown in Fig. 5B. In good agreement with the experiment, we reproduced the three main states (gas, flocking, and vortex) and their correct sequence of transitions for increasing frequency of the applied field (see Fig. 6 and movies S9 to S12). Moreover, the temporal evolution of “computational flocks” closely resembles the experimental ones (as can be seen in Fig. 7A and movie S10), showing a polar order parameter fluctuating around ϕR ≈ 0.3. In agreement with the experimental results, we observed that in the vortex state, all particles move in a single flock, with a rotational order parameter ϕR close to 1 and a “void” with a radius rv ≈10a, (see movie S8). Similar “hollow” vortices were previously observed in the model of interacting self-propelled particles (31). The individual particle behavior (see Fig. 5A) helps to understand the observed collective phenomena. The vortex with the maximal correlation length exists very close to the stability limit of the locked state for an individual particle. In this regime, the individual particles exhibit the most robust rotation, which leads to the emergence of a single vortex. We also observed vortices slightly below the stability limit. Whereas in the absence of fluctuations, individual particles do not rotate, interactions with other particles and the noise can cause the particle to spin. However, their propagation velocity decays with the increase of the frequency. This nonsteady rotation of an individual particle for high frequency leads to transient flocks in the case of collective dynamics. Accordingly, we find a flocking state for low frequencies near the transition from chaotic rotation toward persistent rolling.

Fig. 6. Dynamic states.

(A to D) Snapshots of the emerging dynamic states for H0 = 11 dimensionless units: gas (f = 6 Hz), flocking (f = 20 Hz), vortex (f = 47 Hz), and reentrant flocking (f = 88 Hz) (see also movies S9 to S12). Arrows indicate the velocity of each particle, and the flocks are highlighted by a green background. (E to H) Corresponding intensity plot of the coarse-grained velocity fields.

Fig. 7. Characterization of the dynamic states.

(A) Rotational order parameter φR for gas, flocking, and vortex states as a function of time (normalized by the filed period). (B) Tangential velocity profile for the vortex state as a function of distance from the center. The velocity is scaled by the reduced single-particle velocity αsV0. (C) Spatial particle velocity correlation functions for the different dynamic states; dashed lines correspond to the results including hydrodynamic interactions. Data are shown for the following frequencies: gas (f = 6 Hz), flocking (f = 20 Hz), and vortex (f = 47 Hz). (D) Correlation length Cd as a function of frequency; open symbols denote the results considering hydrodynamic interactions.

We also emphasize a fundamental difference between the two flocking states observed for low and high frequencies. According to Fig. 5A, low-frequency flocking is observed in the regime when an individual particle exhibits a chaotic behavior manifested by spontaneous direction reversals. This implies that external noise does not play a significant role and the emergence of the vortex state is due to the suppression of the intrinsic stochasticity of individual particle motion. We checked through simulations that in this frequency range, the flocking-like motion exists even in the absence of external noise. In contrast, for high-frequency flocking, individual particles would be in a steady state, with their orientation along the field direction. Figure 5C displays the system phase diagram without external noise (DR = 0). Without noise, a stationary phase with hexagonal order emerges (see inset in Fig. 5C). The transition occurs immediately at the boundary between the stationary and rotating states for individual particles (see again Fig. 5A). This observation implies that the high-frequency flocking is a noise-activated process and highlights again that the individual particle dynamics allows one to draw conclusions on the collective phenomena. In the absence of noise, the vortex state emerges only if an individual particle exhibits a robust rotation.

For the results shown in Figs. 5 and 6, we neglected long-range hydrodynamic forces exerted on the fluid by moving rotating particles. The fluid effect was only included in the translational and rotational drag cofficients αt and αr. A rolling particle will impose a net force on the fluid (force monopole or stokeslet). In bulk, the stokeslet velocity would decay as 1/r, where r is the distance from the origin (32). Near a nonslip boundary, the stokeslet will be screened, and in the far field, it will decay as 1/r2 due to an image stokeslet opposite in sign (33). We implemented the hydrodynamic interactions between the particles in the far-field approximation (for the distances large compared to the particle radius a). Our simulations produced no qualitative effect of the hydrodynamic interactions on the overall dynamics of the system (see Fig. 7 and movie S13). This implies that for typical experimental conditions, and except for the immediate vicinity of the particle, the hydrodynamic velocity is small compared to the rolling velocity ωa and can be neglected. All numerically obtained characteristics of the dynamic states (rotational order parameter, tangential velocity profiles, correlation functions, and correlation length dependencies; see Fig. 7) are in qualitative agreement with the experiments (see Fig. 3). However, there are some quantitative differences. First, in the simulations, the obtained correlation length is larger than that in the experiments because all particles are engaged in a vortical motion. In the experiment, even in the case of a vortex, some particles at the periphery move randomly. Second, there is some difference between the vortex tangential velocity profiles. In the experiment, the velocity profile is almost linear within the vortex core, whereas in the simulations, we have a void (see Fig. 7B). We found that the void size shrinks to zero as the number of particles in the system increases.

The onset of flocking and synchronization phenomenon

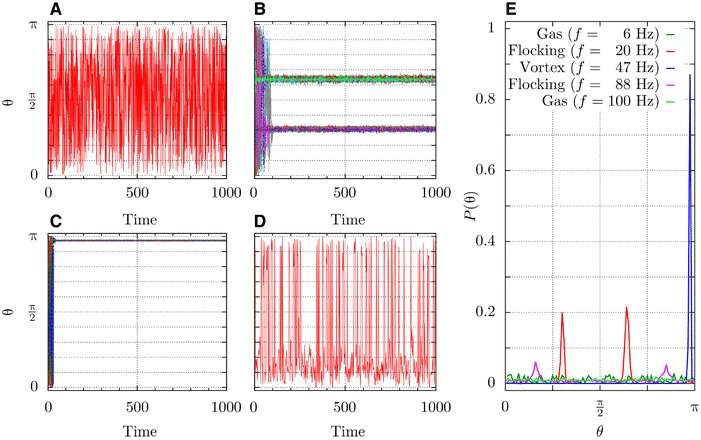

A fundamental question in the context of the onset of large-scale collective behavior is how the increase of spatial coherence relates to the synchronization of particle orientations through the applied ac magnetic field. To address this question, we extracted the particle orientation angles θi at each field period (so-called stroboscopic plots) from the simulation data (see Fig. 8, A to D). The corresponding distribution functions P(θ), plotted after a transitional phase (about 200 periods), for different frequencies are shown in Fig. 8E. Figure 8 reveals a close relation of the phenomenon of phase synchronization and the onset of large-scale collective behavior. As anticipated, in the gas phase (Fig. 8A), the particles execute random-like motion, and their orientations with respect to the field are essentially uncorrelated. Correspondingly, the angle distribution is almost uniform (see Fig. 8). With the onset of flocking, a marked transition occurs (see Fig. 8B). After a short transitional phase, all particle angles converge to two well-separated narrow bands, and the distribution function exhibits two narrow peaks of almost equal heights. The width of the peaks is determined by the noise magnitude DR. We verified that without noise (DR = 0), the peaks become δ-functions. These two peaks in the distribution function P(θ) imply that the flocking phase is composed of two almost equal fractions of clockwise/counterclockwise rolling colloids. Because we do not see transitions between the bands over the entire duration of simulations, it means that the reversal of individual particle directions in low-frequency flocking is very rare. With the transition to a vortex, one of the bands disappears (see Fig. 8C). Correspondingly, the distribution function acquires only one narrow peak. Thus, vortex motion is characterized by the complete synchronization of particle angles with respect to the applied ac field. A further increase of the frequency leads to the breakdown of the synchronized vortex motion and the onset of noise flocking (Fig. 8D). In contrast to the low-frequency flocking shown in Fig. 8B, the high-frequency flocking is noise-activated. It is manifested by a significant amount of unsynchronized particles and relatively small broader peaks in the distribution function. Overall, the observed behavior is reminiscent of the synchronization and clustering phenomena in coupled noisy oscillator systems described by various versions of the Kuramoto model (34–36).

Fig. 8. Particle orientation distributions.

(A to D) Stroboscopic plots of orientation angles θi between the particle magnetic moments and the vertical direction. Angles versus time for all particles in the system is shown in (B) and (C) and only for one particle in (A) and (D) for clarity. Colors mark individual particles, time is measured in the field periods 2π/ω, angles are extracted at the moments of maximal field, and sin(ωt) = 1. Gas phase for f = 6 Hz (A), low-frequency flocking for f = 20 Hz (B), vortex for f = 47 Hz (C), and high-frequency (reentrant) flocking for f = 88 Hz (D). (E) Probability distribution functions for the angles θi for different frequencies.

CONCLUSION

We have demonstrated that a seemingly simple assemblage of rolling ferromagnetic colloids exhibits marked flocking behavior reminiscent of that in living systems. We have identified and characterized three main dynamic phases: gas, flocking, and vortex, as well as the transitions between them. The main advantage of our system compared to other experimental realizations of active matter is that the particle interactions are well characterized and can be tuned by the frequency and magnitude of the magnetic field, solvent viscosity, surface curvature, etc. Moreover, each and every particle can be tracked, and its trajectory can be analyzed. Thus, our work provides insights into a variety of synthetic and living active matter realizations. It also sheds light upon the relation between seemingly unrelated phenomena: the onset of collective behavior and phase synchronization in periodically driven systems. We have demonstrated that the emergence of flocking and vortex motion is manifested by the appearance of sharp peaks in the particle orientations and their synchronization with the ac applied field. Our results also emphasize a subtle role of the rotational noise: whereas one of the flocking phases appears to be noise-insensitive, the reentrant flocking happens to be noise-activated. Thus, our work uncovers new relations between collective motion, synchronization, and self-assembly (37). From the materials perspective, quantification and characterization of the main physical mechanisms governing the dynamics of out-of-equilibrium colloidal systems are crucial for reaching a better understanding of the dynamic self-assembly and self-organization at the microscale.

Our computational model for ferromagnetic rollers accurately reproduced the main experimental observations. We have found that the long-range hydrodynamic forces do not have a qualitative effect on the overall system behavior. However, this does not exclude the importance of near-field hydrodynamic interactions on the dynamics of particles that are almost in contact. In this respect, more accurate characterization of the hydrodynamic forces, for example, by the lattice Boltzmann algorithm (38) or by multiparticle collision dynamics (39), would be highly desirable but is computationally prohibitive.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental setup and image analysis

Nickel spherical particles with an average radius of 60 μm and an average magnetic moment μ = 2 × 10−5 emu (Alfa Aesar Company) were used for the experiments. Particles (up to 400) were dispersed at the bottom of a cylindrical container and filled with isopropanol. The bottom of the container was formed by a concave glass lens with a radius of curvature of 52 mm and a diameter of 50 mm. The particles were energized by a uniform uniaxial alternating magnetic field, H = H0 sin(2πft), created by a custom-built Helmholtz air-core solenoid and applied parallel to the axis of the cylindrical container. The amplitude of the ac magnetic field H0, was in the range of 0 to 75 Oe, and the frequency f, was varied from 20 to 100 Hz.

The container was mounted on a microscope stage (Leica MZ9.5). The trajectories of the particles were monitored by a fast charge-coupled device camera (Redlake MotionPro). We recorded image sequences (resolution, 1280 × 1024 pixels) at a frame rate of 50 frames/s. Image and data analysis of the time sequences were performed by ImageJ, MatPIV, and custom scripts. Particle tracking was carried out by a MATLAB script based on the Crocker and Grier algorithm (40).

The direction of a particle motion was color-coded in visualizations using the following prescription: [red, green, blue] = [(1 + sin(ϕ))/2, (1 + cos(ϕ))/2,0], where φ is the angle of the in-plane velocity vector with respect to the x- axis. The correlation length was determined as an integral of the absolute value of the velocity correlation function C(r).

Discrete particle simulations

Positions and orientations of the particles are described by the following Newton’s equation of motion [compare to models of Kokot et al. (5) and Belkin et al. (41)]

| (10) |

| (11) |

where m is the mass of the particle with radius a, is the magnetic moment directed along the unit vector, I is the moment of inertia, αt = 6πηa = 0.18 is the translation and αr = 0.25 is the rotation drag coefficient, αs = 0.25 is the slipping parameter, is the angular velocity of the particle, is the vector normal to the surface at the particle position, and is the applied external magnetic field with amplitude H0 normalized by a3/μ. To account for the fluctuations due to the shape imperfections of the particles, we included a Gaussian distributed noise term with zero mean and variances , where I is an identity tensor. and are the forces and torques due to the interactions, respectively. Here, we include three contributions, the magnetic dipole-dipole interaction

| (12) |

with the particle distance rij and steric interactions modeled by a short-range hard-core repulsion

| (13) |

Furthermore, the particles are confined in a harmonic potential , with . The particles are assumed to roll down the potential well, which causes an additional torque on the particles. For the unit of length, we chose the radius of the particle a, energy is measured in μ2/a3, and time is measured in αta5/μ2. Hydrodynamic interactions between the particles are included in the far-field approximation (see the Supplementary Materials for details) (42).

The particles are initially placed on a square lattice with random orientations. We equilibrated the system during a time interval of 15,000 field periods and gathered statistics over an interval of at least 30,000 periods of an applied magnetic field (corresponding to 5 to 10 min of the experiment). These simulations were implemented on graphical processing units, and the typical simulation time was about 30 min.

Implementation of hydrodynamic interactions

Hydrodynamic interactions between the particles were included in the far-field approximation by considering the stokeslet and rotlet of spherical particles. Therefore, we added the following hydrodynamic velocity, whose k – th component can be written as

| (14) |

where is the Oseen tensor in Eq. 10 and the hydrodynamic torque in Eq. 11

| (15) |

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, Division of Materials Science and Engineering. A.K. was supported through a Postdoctoral Research Fellowship (KA 4255/1-1) from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG). Author contributions: A.S. and I.S.A. conceived the research, A.S. performed the experiment and analysis of the experimental data, and A.K. and I.S.A. conducted the numerical simulations. All authors wrote the manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/3/2/e1601469/DC1

movie S1. Experimental movie for the gas-like state at frequency f = 20 Hz.

movie S2. Experimental movie for the flocking state at frequency f = 30 Hz.

movie S3. Animation of the experimentally obtained flocking state at frequency f = 30 Hz, where the direction of motion is indicated by the color code.

movie S4. Experimental movie for the vortex state at frequency f = 40 Hz.

movie S5. Animation of the experimentally obtained vortex state at frequency f = 40 Hz, where the direction of motion is indicated by the color code.

movie S6. Experimental movie for the reentrant flocking state at frequency f = 50 Hz.

movie S7. Animation of the experimentally obtained reentrant flocking state at frequency f = 50 Hz, where the direction of motion is indicated by the color code.

movie S8. Experimental movie for the gas-like state at frequency f = 60 Hz.

movie S9. Numerically obtained gas-like state at frequency f = 6 Hz, indicating the direction of motion by the color code.

movie S10. Numerically obtained flocking state at frequency f = 20 Hz, indicating the direction of motion by the color code.

movie S11. Numerically obtained vortex state at frequency f = 47 Hz, indicating the direction of motion by the color code.

movie S12. Numerically obtained reentrant flocking state at frequency f = 88 Hz, indicating the direction of motion by the color code.

movie S13. Numerically obtained vortex state, considering hydrodynamic interactions, at frequency f = 47 Hz, indicating the direction of motion by the color code.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.J. N. Israelachvili, Intermolecular and Surface Forces: Revised Third Edition (Academic Press, ed. 3, 2011), 710 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aranson I. S., Active colloids. Phys. Usp. 56, 79 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Snezhko A., Belkin M., Aranson I. S., Kwok W.-K., Self-assembled magnetic surface swimmers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 118103 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Snezhko A., Aranson I. S., Magnetic manipulation of self-assembled colloidal asters. Nat. Mater. 10, 698–703 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kokot G., Piet D., Whitesides G. M., Aranson I. S., Snezhko A., Emergence of reconfigurable wires and spinners via dynamic self-assembly. Sci. Rep. 5, 9528 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sapozhnikov M. V., Tolmachev Y. V., Aranson I. S., Kwok W.-K., Dynamic self-assembly and patterns in electrostatically driven granular media. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 114301 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan J., Han M., Zhang J., Xu C., Luijten E., Granick S., Reconfiguring active particles by electrostatic imbalance. Nat. Mater. 15, 1095–1099 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solis K. J., Martin J. E., Stimulation of vigorous rotational flows and novel flow patterns using triaxial magnetic fields. Soft Matter 8, 11989–11994 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin J. E., On the origin of vorticity in magnetic particle suspensions subjected to triaxial fields. Soft Matter 12, 5636–5644 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bricard A., Caussin J.-B., Desreumaux N., Dauchot O., Bartolo D., Emergence of macroscopic directed motion in populations of motile colloids. Nature 503, 95–98 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bricard A., Caussin J.-B., Das D., Savoie C., Chikkadi V., Shitara K., Chepizhko O., Peruani F., Saintillan D., Bartolo D., Emergent vortices in populations of colloidal rollers. Nat. Commun. 6, 7470 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leunissen M. E., Christova C. G., Hynninen A.-P., Royall C. P., Campbell A. I., Imhof A., Dijkstra M., van Roij R., van Blaaderen A., Ionic colloidal crystals of oppositely charged particles. Nature 437, 235–240 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palacci J., Sacanna S., Steinberg A. P., Pine D. J., Chaikin P. M., Living crystals of light-activated colloidal surfers. Science 339, 936–940 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vicsek T., Zafeiris A., Collective motion. Phys. Rep. 517, 71–140 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vicsek T., Czirók A., Ben-Jacob E., Cohen I., Shochet O., Novel type of phase transition in a system of self-driven particles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 1226–1229 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grégoire G., Chaté H., Onset of collective and cohesive motion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 025702 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ginelli F., Peruani F., Bär M., Chaté H., Large-scale collective properties of self-propelled rods. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 184502 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peshkov A., Aranson I. S., Bertin E., Chaté H., Ginelli F., Nonlinear field equations for aligning self-propelled rods. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 268701 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deseigne J., Dauchot O., Chaté H., Collective motion of vibrated polar disks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 098001 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sumino Y., Nagai K. H., Shitaka Y., Tanaka D., Yoshikawa K., Chaté H., Oiwa K., Large-scale vortex lattice emerging from collectively moving microtubules. Nature 483, 448–452 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaller V., Weber C., Semmrich C., Frey E., Bausch A. R., Polar patterns of driven filaments. Nature 467, 73–77 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanchez T., Chen D. T. N., DeCamp S. J., Heymann M., Dogic Z., Spontaneous motion in hierarchically assembled active matter. Nature 491, 431–434 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin J. E., Snezhko A., Driving self-assembly and emergent dynamics in colloidal suspensions by time-dependent magnetic fields. Rep. Prog. Phys. 76, 126601 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou S., Sokolov A., Lavrentovich O. D., Aranson I. S., Living liquid crystals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 1265–1270 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quincke G., Über rotationen im constanten electrischen felde. Ann. Phys. 295, 417–486 (1896). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Löber J., Ziebert F., Aranson I. S., Collisions of deformable cells lead to collective migration. Sci. Rep. 5, 9172 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Howse J. R., Jones R. A. L., Ryan A. J., Gough T., Vafabakhsh R., Golestanian R., Self-motile colloidal particles: From directed propulsion to random walk. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 048102 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cherukat P., McLaughlin J. B., The inertial lift on a rigid sphere in a linear shear flow field near a flat wall. J. Fluid Mech. 263, 1–18 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 29.M. Abramowitz, I. A. Stegun, Handbook of Mathematical Functions: With Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables (Courier Corporation, 1964), 1046 pp.

- 30.Zaslavskiĭ G. M., Chirikov B. V., Stochastic instability of non-linear oscillations. Phys. Usp. 14, 549–568 (1972). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levine H., Rappel W.-J., Cohen I., Self-organization in systems of self-propelled particles. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 63, 017101 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.S. Kim, S. J. Karrila, Microhydrodynamics: Principles and Selected Applications (Courier Corporation, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blake J. R., A note on the image system for a stokeslet in a no-slip boundary. Math. Proc. Camb. Philos. Soc. 70, 303–310 (1971). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Acebrón J. A., Bonilla L. L., Vicente C. J. P., Ritort F., Spigler R., The Kuramoto model: A simple paradigm for synchronization phenomena. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77, 137 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Golomb D., Hansel D., Shraiman B., Sompolinsky H., Clustering in globally coupled phase oscillators. Phys. Rev. A 45, 3516–3530 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenblum M. G., Pikovsky A. S., Kurths J., Phase synchronization of chaotic oscillators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 1804–1807 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yan J., Bloom M., Bae S. C., Luijten E., Granick S., Linking synchronization to self-assembly using magnetic janus colloids. Nature 491, 578–581 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.S. Succi, The Lattice Boltzmann Equation: For Fluid Dynamics and Beyond (Oxford Univ. Press, 2001), 288 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malevanets A., Kapral R., Mesoscopic model for solvent dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 110, 8605–8613 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crocker J. C., Grier D. G., Methods of digital video microscopy for colloidal studies. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 179, 298–310 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Belkin M., Glatz A., Snezhko A., Aranson I. S., Model for dynamic self-assembled magnetic surface structures. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 82, 015301 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spagnolie S. E., Lauga E., Hydrodynamics of self-propulsion near a boundary: Predictions and accuracy of far-field approximations. J. Fluid Mech. 700, 105–147 (2012). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/3/2/e1601469/DC1

movie S1. Experimental movie for the gas-like state at frequency f = 20 Hz.

movie S2. Experimental movie for the flocking state at frequency f = 30 Hz.

movie S3. Animation of the experimentally obtained flocking state at frequency f = 30 Hz, where the direction of motion is indicated by the color code.

movie S4. Experimental movie for the vortex state at frequency f = 40 Hz.

movie S5. Animation of the experimentally obtained vortex state at frequency f = 40 Hz, where the direction of motion is indicated by the color code.

movie S6. Experimental movie for the reentrant flocking state at frequency f = 50 Hz.

movie S7. Animation of the experimentally obtained reentrant flocking state at frequency f = 50 Hz, where the direction of motion is indicated by the color code.

movie S8. Experimental movie for the gas-like state at frequency f = 60 Hz.

movie S9. Numerically obtained gas-like state at frequency f = 6 Hz, indicating the direction of motion by the color code.

movie S10. Numerically obtained flocking state at frequency f = 20 Hz, indicating the direction of motion by the color code.

movie S11. Numerically obtained vortex state at frequency f = 47 Hz, indicating the direction of motion by the color code.

movie S12. Numerically obtained reentrant flocking state at frequency f = 88 Hz, indicating the direction of motion by the color code.

movie S13. Numerically obtained vortex state, considering hydrodynamic interactions, at frequency f = 47 Hz, indicating the direction of motion by the color code.