ABSTRACT

Listeria monocytogenes is a foodborne pathogen that can cause severe disease (listeriosis) in susceptible individuals. It is ubiquitous in the environment and often exhibits resistance to heavy metals. One of the determinants that enables Listeria to tolerate exposure to cadmium is the cadAC efflux system, with CadA being a P-type ATPase. Three different cadA genes (designated cadA1 to cadA3) were previously characterized in L. monocytogenes. A novel putative cadmium resistance gene (cadA4) was recently identified through whole-genome sequencing, but experimental confirmation for its involvement in cadmium resistance is lacking. In this study, we characterized cadA4 in L. monocytogenes strain F8027, a cadmium-resistant strain of serotype 4b. By screening a mariner-based transposon library of this strain, we identified a mutant with reduced tolerance to cadmium and that harbored a single transposon insertion in cadA4. The tolerance to cadmium was restored by genetic complementation with the cadmium resistance cassette (cadA4C), and enhanced cadmium tolerance was conferred to two unrelated cadmium-sensitive strains via heterologous complementation with cadA4C. Cadmium exposure induced cadA4 expression, even at noninhibitory levels. Virulence assessments in the Galleria mellonella model suggested that a functional cadA4 suppressed virulence, potentially promoting commensal colonization of the insect larvae. Biofilm assays suggested that cadA4 inactivation reduced biofilm formation. These data not only confirm cadA4 as a novel cadmium resistance determinant in L. monocytogenes but also provide evidence for roles in virulence and biofilm formation.

IMPORTANCE Listeria monocytogenes is an intracellular foodborne pathogen causing the disease listeriosis, which is responsible for numerous hospitalizations and deaths every year. Among the adaptations that enable the survival of Listeria in the environment are the abilities to persist in biofilms, grow in the cold, and tolerate toxic compounds, such as heavy metals. Here, we characterized a novel determinant that was recently identified on a larger mobile genetic island through whole-genome sequencing. This gene (cadA4) was found to be responsible for cadmium detoxification and to be a divergent member of the Cad family of cadmium efflux pumps. Virulence assessments in a Galleria mellonella model suggested that cadA4 may suppress virulence. Additionally, cadA4 may be involved in the ability of Listeria to form biofilms. Beyond the role in cadmium detoxification, the involvement of cadA4 in other cellular functions potentially explains its retention and wide distribution in L. monocytogenes.

KEYWORDS: Listeria monocytogenes, cadmium resistance, cadA, biofilm, virulence

INTRODUCTION

Listeria monocytogenes is a Gram-positive rod-shaped bacterium widely distributed in nature (1). As a facultative intracellular foodborne pathogen causing the disease listeriosis, L. monocytogenes organisms are responsible for numerous hospitalizations and deaths in the United States every year (2). To facilitate its survival in a diverse array of conditions, L. monocytogenes possesses an equally diverse array of determinants, including the abilities to persist in biofilms, grow in the cold, and tolerate a variety of toxic compounds, such as heavy metals, disinfectants, and dyes (3–6). In particular, heavy metals in the environment can exert long-term selective pressure on bacteria (7), as heavy metals do not degrade over time. It is worthy of note that several major foodborne outbreaks of listeriosis have involved cadmium-resistant L. monocytogenes strains (8). Interestingly, cadmium resistance in L. monocytogenes has been found to occur more commonly among strains repeatedly isolated from foods than from those encountered only sporadically (9).

One of the determinants shown to mediate cadmium resistance in L. monocytogenes is the CadAC efflux cassette, comprising the heavy metal-translocating P-type ATPase, CadA, and its putative repressor, CadC (4, 10). Three members of the CadAC family were previously identified in L. monocytogenes. Of these, CadA1 and CadA2 were found to be harbored by plasmids and to be widely distributed among different strains and serotypes of L. monocytogenes (4, 10–13), while CadA3 is encoded chromosomally and has only been identified in strain EGD-e and a few others (11, 14, 15). The expression of cadC (Lmo1102) from strain EGD-e was markedly upregulated in vivo in a murine infection model and experimentally confirmed to be required for virulence in that model (16). Another P-type ATPase associated with iron homeostasis has been shown to be required for virulence in L. monocytogenes (17). However, limited information is available overall on the potential impacts of heavy metal tolerance in the virulence and persistence of L. monocytogenes.

Genome sequencing of L. monocytogenes strain Scott A, a clinical isolate from a 1979 listeriosis outbreak in Boston in which contaminated vegetables were epidemiologically implicated (18), identified a putative new member of the CadA family (tentatively termed CadA4) within a large (∼35kb) genomic island in the chromosome of this strain (19). The gene cadA4 was also detected in another strain from this outbreak (20) and in additional strains (14), including in 29% of serotype 4b isolates from sporadic human listeriosis cases in the United States from 2005 to 2008 (8). The majority of these cadA4-harboring isolates were members of the same clonal complex as Scott A (CC2, also previously referred to as epidemic clone [EC]Ia or ECIV) (8). An unusual attribute of cadA4 is that it was associated with growth at 35 μg/ml cadmium chloride but not at 70 μg/ml, whereas strains harboring cadA1 to cadA3 grew at cadmium concentrations up to and often exceeding 140 μg/ml (8, 12).

In spite of the intriguing attributes of cadA4 in L. monocytogenes, direct experimental evidence for its involvement in cadmium resistance has been lacking. In addition, no information has been reported on the potential impacts of this determinant in virulence or other adaptations to account for its presence and retention by L. monocytogenes CC2 and other strains, even in the absence of exposure to cadmium. In this study, we characterized the role of cadA4 in cadmium resistance of the serotype 4b cadA4-harboring strain L. monocytogenes F8027, originally isolated from celery, and we described other functional characteristics associated with this cadmium-resistance gene cassette.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Insertional inactivation of cadA4 is accompanied by a pronounced decrease in cadmium tolerance.

L. monocytogenes strain F8027 (hereafter F8027) was originally derived from fresh celery and has been used as model in studies for produce colonization by L. monocytogenes (21). It grew at 35 but not at 50 μg/ml cadmium chloride, hence its MIC (50 μg/ml) is below the 70 μg/ml threshold for resistance used in previous studies (11, 12, 22). PCR with previously described primers (8) indicated that F8027 was negative for previously identified cadmium resistance determinants cadA1, cadA2, and cadA3 (data not shown). However, PCR with primers P30 and P31 (8) specific to cadA4, identified through the genome sequencing of Scott A (19), yielded the expected product (data not shown). Cadmium MICs of F8027 in the presence of the efflux inhibitor reserpine were reduced to 20 μg/ml, suggesting that the observed cadmium tolerance of this strain was at least partly mediated by efflux mechanisms, as also noted for another cadmium resistance determinant in L. monocytogenes, cadA2 (23).

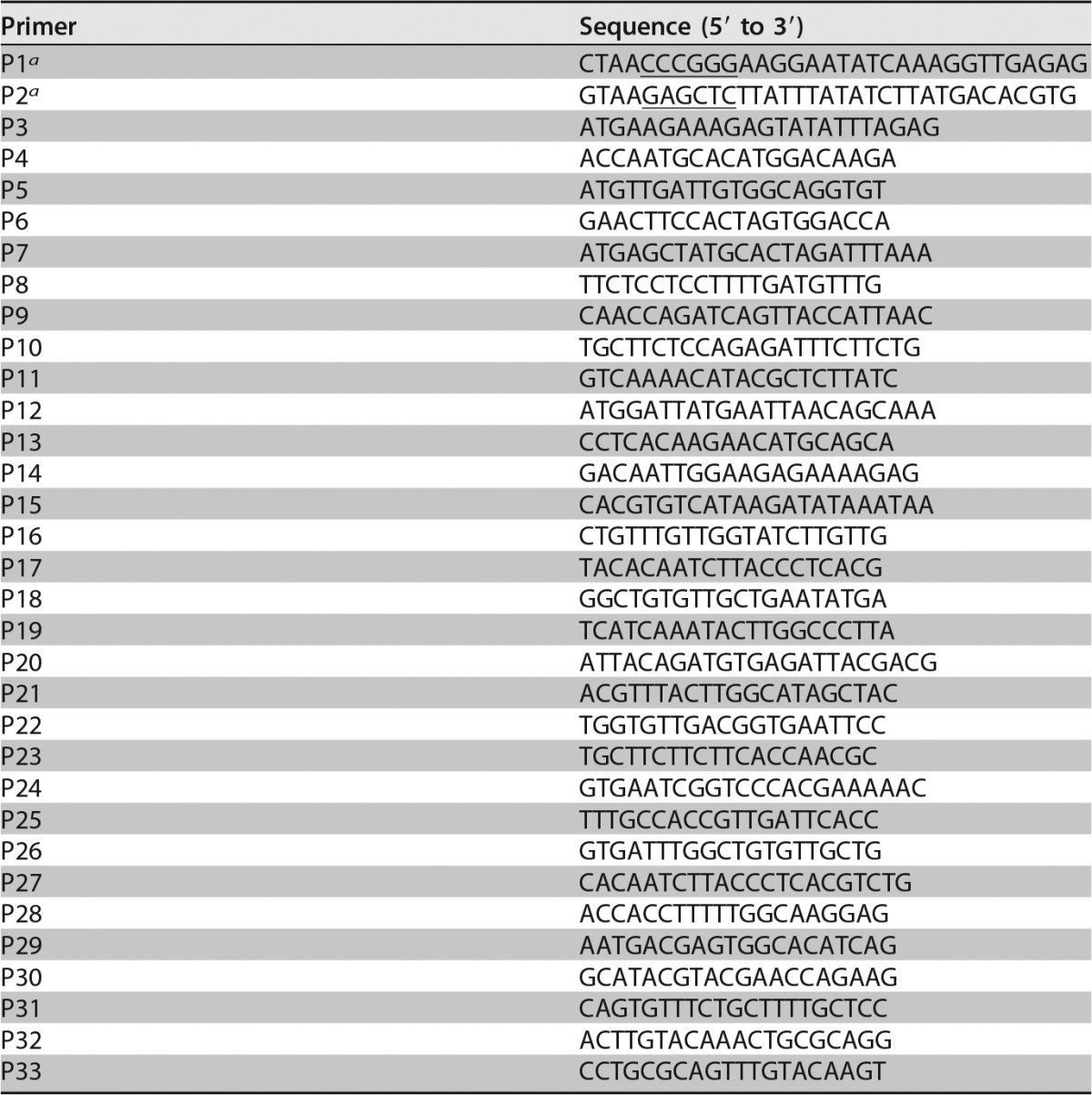

By screening a mariner-based library (approximately 2,000 mutants) on Iso-Sensitest agar (ISA) with cadmium (35 μg/ml), we identified four mutants with markedly reduced or no visible growth. PCR with cadA4-targeting primers P3 and P4 (Table 1) revealed that one mutant, I1A2, generated a larger PCR product (∼2.5 kb) than F8027 (∼1 kb) (data not shown), suggesting that it harbored a transposon insertion in cadA4. I1A2 also exhibited the most noticeable impairment of growth in the presence of cadmium (MIC, 10 μg/ml) (Table 2), while the other three mutants had higher (15 to 25 μg/ml) MICs for cadmium and harbored insertions in unrelated loci (data not shown). By sequencing the cadA4-derived PCR amplicon from mutant I1A2, we localized the transposon at nucleotide (nt) 1,059 of the cadA4 coding region (2,103 nt). A Southern blot analysis showed that I1A2 harbored a single copy of the transposon (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Primers used in this study

Underlined CCCGGG and GAGCTC sequences are restriction sites for XmaI and SacI, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Strain | Description/source/reference |

|---|---|

| Listeria monocytogenes | |

| F8027 | Serotype 4b strain from celery (21) |

| I1A2 | Mariner-based transposon mutant of F8027 with transposon insertion in cadA4 |

| I1A2_pPL2 | I1A2 with empty shuttle vector pPL2 integrated into the chromosome |

| I1A2::cadA4 | Genetically complemented I1A2, with pPL2_cadA4 integrated into the chromosome |

| H7550-Cds | Cadmium-susceptible derivative of L. monocytogenes H7550 (26) |

| H7550-Cds_pPL2 | H7550-Cds with empty shuttle vector pPL2 integrated into the chromosome |

| H7550-Cds::cadA4 | H7550-Cds with pPL2_cadA4 integrated into the chromosome |

| F2365 | Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b strain (cadmium susceptible) (24) |

| F2365_pPL2 | F2365 with empty shuttle vector pPL2 integrated into the chromosome |

| F2365::cadA4 | F2365 with pPL2_cadA4 integrated into the chromosome |

| I1A2::cadA4SDM | I1A2 with pPL2_cadA4SDM integrated into the chromosome |

| Escherichia coli | |

| DH5α | Invitrogen |

| DH5α_pPL_cadA4 | E. coli DH5α harboring pPL2_cadA4 |

| DH5α_pPL_cadA4SDM | E. coli DH5α harboring pPL2_cadA4SDM |

| S17-1_pPL_cadA4 | E. coli S17-1 (43) harboring pPL2_cadA4 |

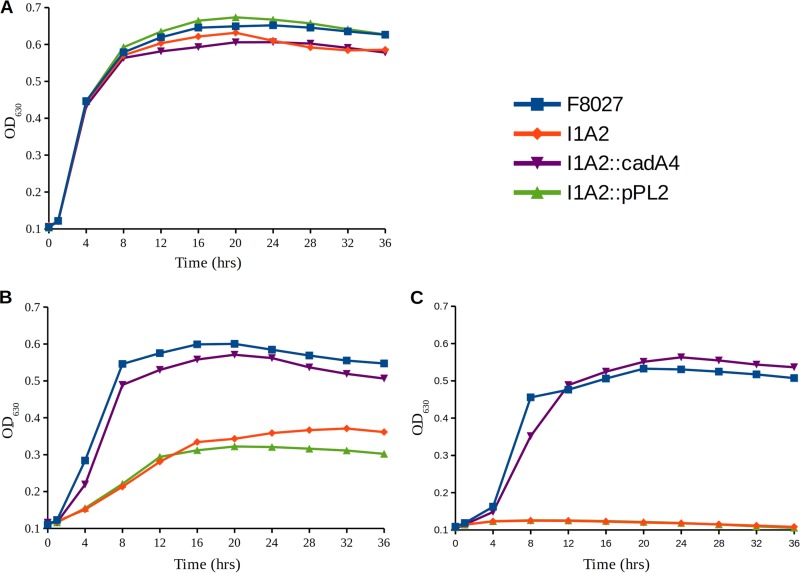

No difference in growth was observed between F8027 and I1A2 strains at 37°C in brain heart infusion (BHI) (Fig. 1A). However, the growth of I1A2 was markedly inhibited in the presence of 5 μg/ml cadmium (Fig. 1B), with complete inhibition at 10 μg/ml (Fig. 1C). Growth at the lower, more environmentally relevant levels of 1.6 and 0.1 μg/ml was not different between F8027 and I1A2 at 37 or 28°C (data not shown). MICs of I1A2 to arsenic, zinc, and copper were not affected (data not shown), suggesting that cadA4 was specifically associated with cadmium tolerance. Previous studies with the plasmid-associated cadA determinant cadA1 also revealed that it mediated resistance to cadmium, but not to zinc, in spite of its homology with cadA from Staphylococcus aureus, which conferred resistance to both cadmium and zinc (4). Additionally, neither cadA2 nor cadA3 were associated with resistance to zinc (C. Parsons and S. Kathariou, unpublished data).

FIG 1.

Impact of cadA4 inactivation on growth of L. monocytogenes F8027 in the presence of cadmium. Growth curves for F8027, I1A2, I1A2 harboring the empty vector (I1A2::pPL2), and the genetically complemented mutant (I1A2:: pPL2_cadA4) were determined for growth in BHI (A), BHI with 5 μg/ml CdCl2 (B), and BHI with 10 μg/ml CdCl2 (C). Bacteria were grown in 96-well plates at 37°C for 36 h, and OD630 was monitored using a BioTek Elx808. Data represent averages of readings from six separate wells from one representative experiment.

We could not distinguish I1A2 from its parental counterpart in other routine phenotypic assays. It exhibited no discernible differences from F8027 in motility, growth at 4°C, hemolytic activity on blood agar plates, cell shape, and colony morphology. With the exception of resistance to erythromycin (conferred by the transposon), I1A2 was not distinguishable from F8027 in its susceptibility to a panel of antibiotics, tested as described in Materials and Methods (M. Jacob, personal communication).

CadA4 is a CadA family member divergent from CadA1, CadA2, and CadA3 and is associated with lower cadmium MICs.

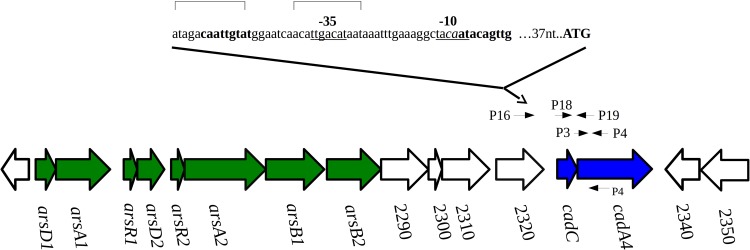

Analysis of the results from sequencing of the F8027 cadAC revealed 100% identity to its counterpart in Scott A. Furthermore, PCR with primers derived from sequences flanking cadA4 in Scott A indicated that in F8027, the cadAC cassette was flanked by the same genes as in Scott A (Fig. 2 and data not shown). An additional analysis, to be described in a separate publication, suggested that cadA4 in F8027 was harbored by a genomic island with several arsenic detoxification genes and is highly conserved with its Scott A counterpart, but inserted in a different chromosomal location (data not shown).

FIG 2.

Genomic organization of the cadA4 region within Listeria genomic island 2. Putative −35 and −10 sequences are underlined; ATG indicates cadA start codon. Bracketed sequences signify putative DNA binding sites (4). Predicted inverted repeat sequences are indicated in bold font. P4 indicates the cDNA primer used for RT-PCR. The cadAC ORFs are indicated in blue, and ORFs putatively associated with arsenic detoxification are in green. Arrow orientations of ORFs indicate the direction of transcription. PCR primers are denoted by small arrows.

A BLAST analysis showed highly conserved (99 to 100% at the nt sequence level) cadA4 homologs in several other L. monocytogenes genomes. There were also similarly conserved (90 to 99% identity) homologs in Enterococcus cecorum strains CE1 and CE2 and E. faecalis strain KB1 (87% identity). Less conserved (71 to 72% identity at the nt sequence level and 63 to 61% identity of the deduced polypeptides) cadA4 homologs were identified in Clostridium botulinum strain BTK015925, several strains of Bacillus cereus (FORC_005, B4264, J17, A1, and S2-8), and the insect pathogen B. thuringiensis strain BT185 (data not shown). The genomic island harboring cadA4 in Scott A was highly similar to a mobile genetic element (MGE) in Enterococcus faecalis JH1 (19) (data not shown). However, the E. faecalis MGE lacked cadA4, suggesting that cadA4 in L. monocytogenes was incorporated into an arsenic resistance genomic island similar to that detected in E. faecalis strain JH1. The GC contents of the Scott A and F8027 cadAC sequences (33.6%) are noticeably lower than the average (38%) for L. monocytogenes genomes (15, 24), suggesting horizontal gene transfer-mediated acquisition of this cadmium resistance cassette.

As mentioned earlier, cadA4-harboring strains of L. monocytogenes tolerate smaller amounts of cadmium (MIC, 50 μg/ml) than those harboring cadA1, cadA2, or cadA3 (MIC, ≥140 μg/ml), unless they concurrently harbor one of the latter determinants (8). The underlying reasons remain unknown, but it is tempting to speculate that they are attributable to the sequence diversity of cadA (Fig. 3). While cadA1, cadA2, and cadA3 share ca. 70% identity at the amino acid (aa) sequence level, cadA4 is noticeably divergent, exhibiting only ca. 36% identity with these other cadA determinants (11). Nonetheless, the deduced CadA encoded by cadA4 harbored all three key motifs characteristic of the CadA protein family (25): CXXC, responsible for metal binding; DKTGT, associated with ATP binding; and CXC, specifically CPC, serving as a membrane-bound ion transport channel (Fig. 3). These key motifs were also present in the B. cereus and B. thuringiensis homologs (data not shown). It is noteworthy that, in contrast to the DKTGT and CPC motifs that were conserved in CadA1 to CadA4, the metal binding motif CXXC was different in CadA4 (CANC) than in CadA1 to CadA3 (CTNC, in all three sequences).

FIG 3.

Amino acid alignment of four identified members of the CadA family in Listeria. Key functional motifs are outlined in red. CXXC, metal binding domain; CXC, ion channel; DKTGT, ATPase.

We hypothesized that the observed amino acid substitution in such a key motif may account for the reduced tolerance to cadmium associated with CadA4, in comparison to CadA1 to CadA3. However, site-directed mutagenesis-based alteration of the CANC sequence to the consensus CTNC found in CadA1 to CadA3 modestly reduced the MIC (40 μg/ml versus 50 μg/ml, respectively, for F8027). It is conceivable that the unique CANC motif in CadA4 works together with other elements of the polypeptide sequence to mediate the observed levels of tolerance to cadmium, and that other CadA4C features may also contribute to the difference in tolerance to cadmium conferred by CadA4C, in comparison to CadA1C, CadA2C, and CadA3C. This is also supported by findings from heterologous expression of cadA4C in unrelated L. monocytogenes strains, to be discussed below.

Genetic complementation and heterologous expression confirm involvement of cadA4 in cadmium tolerance.

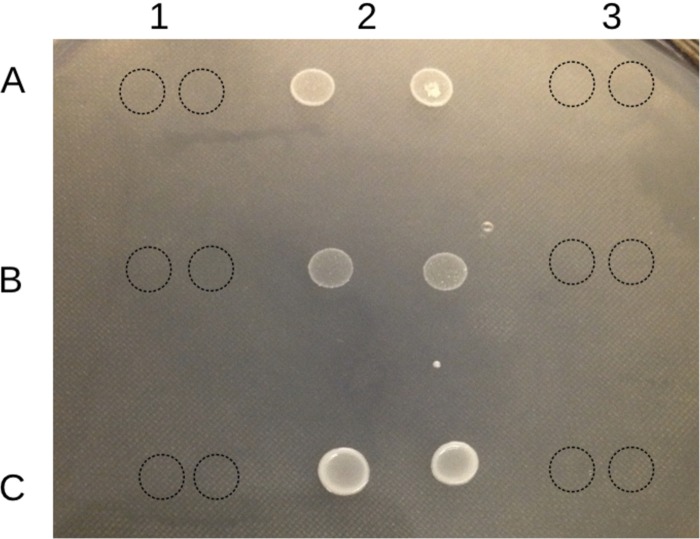

A putative promoter was identified in the intergenic region upstream of LMOSA_2321 (cadC) in Scott A, along with a pair of inverted repeats (ΔG −33.6), one of which overlapped the putative −10 box of the promoter (Fig. 2). These inverted repeats were similar (identical in 11/13 nucleotides) with those previously identified in the −35 putative promoter region of cadA1C and were hypothesized to be involved in the transcriptional regulation of cadA1C (4). Mobilization of cadA4C together with the upstream intergenic region harboring the putative promoter into the cadmium-sensitive mutant I1A2 completely restored the cadmium tolerance (cadmium MIC, 50 μg/ml) (Fig. 4).

FIG 4.

Growth of genetically complemented strains on ISA supplemented with 35 μg/ml CdCl2. Row A, mutant I1A2, complemented I1A2 (I1A2::pPL2_cadA4), and I1A2 harboring empty vector (I1A2::pPL2) in columns 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Row B, F2365, complemented F2365 (F2365::pPL2_cadA4), and F2365 harboring empty vector (F2365::pPL2), in columns 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Row C, H7550-Cds, complemented H7550-Cds (H7550-Cds::pPL2_cadA4), and H7550-Cds harboring empty vector (H7550-Cds::pPL2), in columns 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Cell suspensions (4 μl) were spotted in duplicate on the surface of the plate, which was dried and incubated at 37°C for 48 h. Dotted circles indicate the locations of spots with no observed growth.

Heterologous expressions of cadA4C in two unrelated cadmium-susceptible L. monocytogenes strains, F2365 and H75550-Cds, also conferred similar levels of cadmium tolerance (MIC, 50 μg/ml, in contrast to 10 μg/ml for the respective parental strains) (Fig. 4). Strains F2365 and H75550-Cds chosen for heterologous expressions of cadA4C belong to clonal complexes CC1 (also known as ECI) and CC6 (also known as ECII), respectively, markedly distinct from either F8027 (CC315) or Scott A (CC2). H75550-Cds is a plasmid (pPL80)-cured derivative of strain H7550, implicated in the 1998 to 1999 hotdog outbreak (26); pLM80 harbors cadA2C (24), and H7550 grew at cadmium concentrations >140 μg/ml, similar to other cadA2-harboring strains (11). However, upon acquisition of cadA4C, cadmium MICs for both F2365 and H75550-Cds increased to only 50 μg/ml, i.e., a level characteristic for F8027 and other strains that naturally harbor cadA4. Thus, this resistance level is associated with the cadA4C cassette itself and is exhibited in strains with diverse genomic backgrounds and with much higher cadmium MICs when harboring a different cadA determinant.

Expression of cadA4 is induced by cadmium, and cadA4C is a bicistronic unit transcribed independently from the upstream arsenic resistance gene cluster.

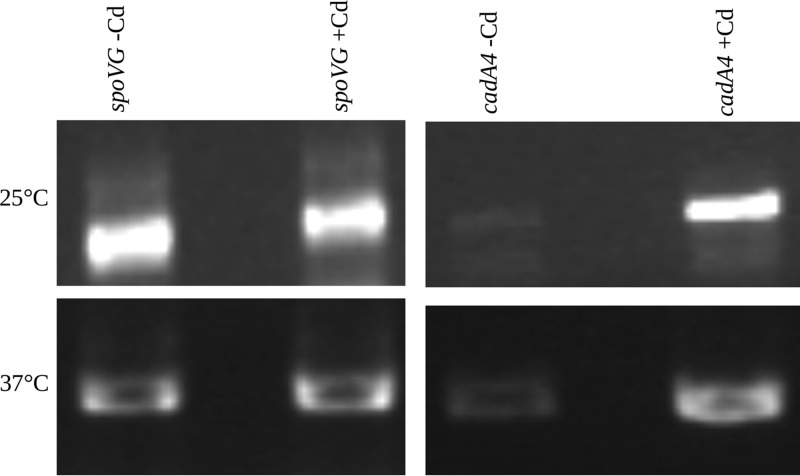

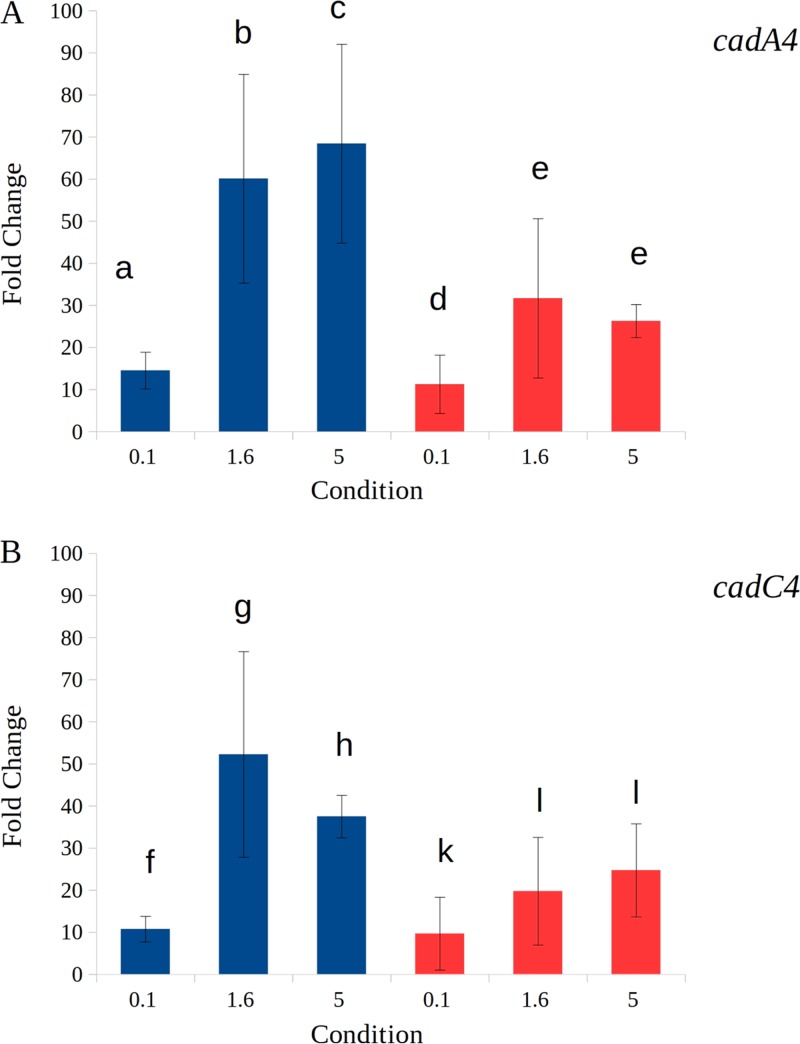

Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR of cDNA performed with primer P4 indicated that basal levels of cadA4 were low but detectible, both at 25 and 37°C, but markedly increased upon exposure to cadmium (Fig. 5). When this cDNA was used as a template with primers P18 and P19 (Fig. 2), the expected PCR product was obtained (data not shown), suggesting that cadA4 and cadC were cotranscribed. In contrast, PCR with primers P16 and P19 (Fig. 2) failed to yield any product, suggesting that cadA4C was a bicistronic unit and not cotranscribed with the upstream LMOSA_2320 (data not shown). These data were supported by quantitative PCR (qPCR) assays, which showed that cadA4 was induced in the presence of 5 μg/ml cadmium at 25 and 37°C with 65- and 26-fold increases, respectively (Fig. 6A). At more environmentally relevant cadmium levels, e.g., 1.6 μg/ml, there was a 53-fold increase in cadA4 expression at 25°C, with a lower (15-fold) increase at 37°C (Fig. 6A). Increases were also noted at even lower cadmium levels (0.1 μg/ml), even though they were lower than those at 1.6 μg/ml, i.e., 14- and 9-fold at 25 and 37°C, respectively (Fig. 6A). cadC was also induced in the presence of cadmium (0.1, 1.6, and 5 μg/ml) at 25 and 37°C (Fig. 6B).

FIG 5.

Reverse transcription assessment of cadA4 induction by cadmium at 25° and 37°C. Cultures were exposed to 5 μg/ml cadmium (lanes indicated as +Cd) or left untreated (lanes indicated as −Cd) for 30 min at 25° (top) or 37°C (bottom). The housekeeping gene spoVG was used as a control, and experiments were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Data are from one representative experiment.

FIG 6.

Relative gene expression of cadA4 (A) and cadC4 (B) at 25° and 37°C at various concentrations of cadmium. Columns in blue indicate 25°C treatments, while those in red indicate treatments at 37°C. The numbers below the columns represent the cadmium concentration (μg/ml). Data were from at least three independent trials of real-time PCR carried out as described in Materials and Methods. For each gene, comparisons were made across temperatures and concentrations via paired Student's t test, and significant differences (P < 0.05) are indicated by differing letters. The error bars represent standard errors.

LMOSA_2320, immediately upstream of the cadA4C cassette, was minimally induced (3-fold increase) with exposure to cadmium (5 μg/ml) at 25°C, with no evidence for induction at 37°C (data not shown). Several other open reading frames (ORFs) upstream of cadA4 (arsB2, arsB1, arsA2, etc.) appear to be involved in arsenic detoxification and are transcribed in the same direction as cadA4C (Fig. 2). However, exposure to arsenic did not induce expression of cadA4 (data not shown). Taken together, the transcriptional data suggest that cadA4 was transcribed independently from LMOSA_2320 and other upstream sequences and was induced by exposure to cadmium, even at trace levels.

Two elements in the cadmium-dependent induction of cadA4C are worthy of note. First, the expressions of cadA4 and cadC induced at all tested cadmium levels were higher at 25°C than at 37°C, suggesting especially high induction at environmental temperatures. Nonetheless, the finding that both genes were still induced by cadmium at 37°C also suggests a potential involvement in virulence in warm-blooded animals, which remains to be further investigated. Second, induction was noted at cadmium levels low enough to not detectably inhibit growth, similar to the results from earlier reports where trace amounts of cadmium induce expression of cadA1C (4). While all the levels of cadmium we tested might represent high levels of contamination in most environments, cadmium levels can be unusually high in certain habitats via not only anthropogenic contamination but also bioaccumulation in plant and animal tissues (27). This suggests a potentially significant role of determinants such as cadA4C in the environmental survival and adaptation of L. monocytogenes, particularly in habitats impacted by natural or anthropogenic cadmium contamination.

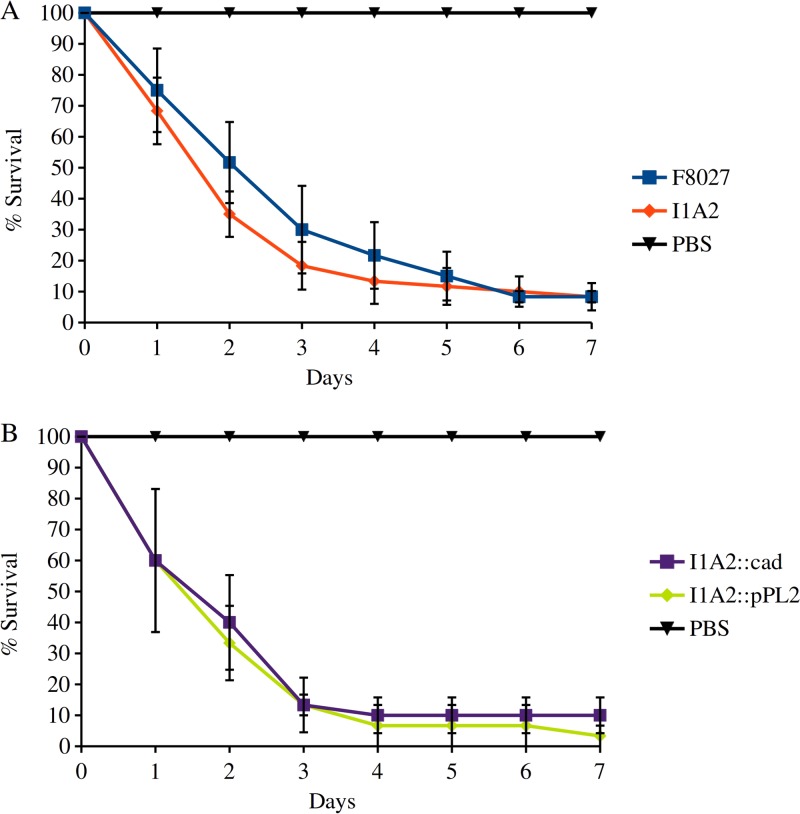

Inactivation of cadA4 enhances virulence in Galleria mellonella.

Inoculating G. mellonella larvae with ca. 106 CFU of F8027, I1A2, genetically complemented I1A2, and I1A2 harboring the empty vector pPL2 and monitoring larval survival at 37°C revealed a steep decline in survival in the first 5 days postinoculation (Fig. 7A). I1A2-inoculated larvae exhibited higher mortality than those inoculated with the parental strain F8027, with the difference being significant (P = 0.0182) when analyzed with the paired Student's t test, but not with the nonparametric proportional hazards survival model (P = 0.4095). The presence of pPL2 alone appeared to enhance the virulence of I1A2, and while the cadA4C-complemented I1A2 was less virulent than I1A2 harboring pPL2 alone, the difference between the two did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 7B). In addition to the apparent impact of the vector, another potential complication was that the complemented I1A2 harbored the entire cadA4C cassette, and thus possessed two functional cadC copies but only one functional copy of cadA4.

FIG 7.

Impact of cadA4 in the Galleria mellonella model. Larvae were inoculated with F8027 and I1A2 (A) or I1A2::pPL2_cadA4 and I1A2::pPL2 (B), incubated at 37°C, and monitored daily for 7 days as described in Materials and Methods. Data are averages from at least three independent trials. Strains were as described in legend of Fig. 4 and Table 2. Error bars represent standard errors.

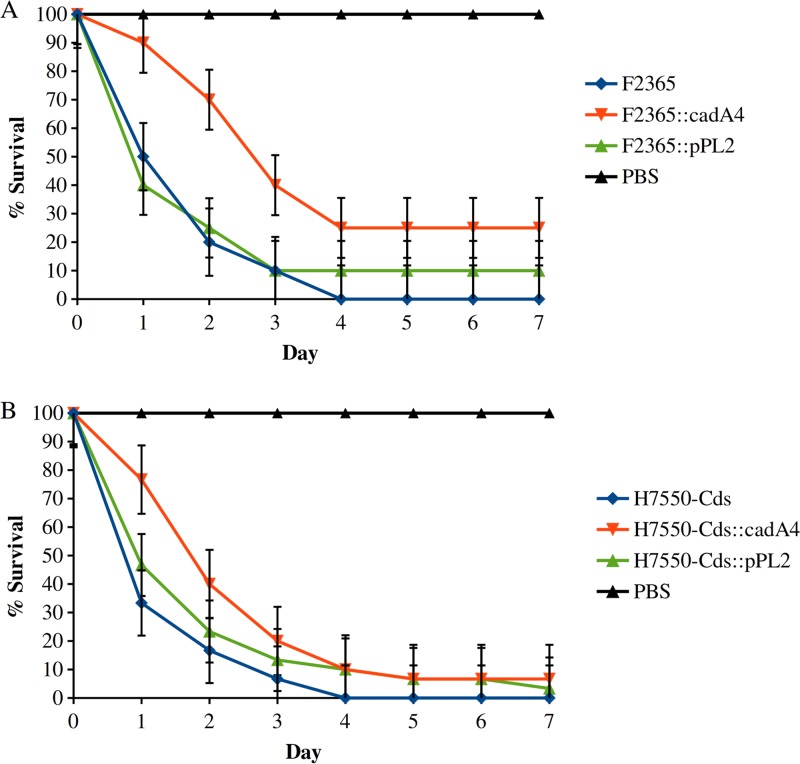

To avoid the latter issue, we heterologously expressed cadA4C constructs in strains F2365 and H7550-Cds (Fig. 8). Larvae inoculated with either construct exhibited higher survival than those inoculated with the corresponding parental strains, with the differences being significant according to the paired Student's t test (F2365, P = 0.0015; H7550-Cds, P = 0.0036) and the nonparametric proportional hazards survival model (F2365, P = 0.0402; H7550-Cds, P = 0.0334) (Fig. 8). Virulence of the parental strains was not significantly impacted by the presence of the empty vector (F2365, P = 0.5; H7550-Cds, P = 0.1723) (Fig. 8).

FIG 8.

Impacts of heterologously expressed cadA4C constructs of F2365 (A) and H7550-Cds (B) in the Galleria mellonella model. Data are from three independent trials. Strains were as described in the legend of Fig. 4 and in Table 2. Error bars represent standard errors.

Interestingly, reduced virulence in Galleria was reported earlier for strain Scott A, which harbors the same cadA4-containing island as F8027. Compared with the other strains tested in the Galleria model in that study, Scott A exhibited the least virulence (28). Intriguing virulence impacts were also identified earlier for another L. monocytogenes gene implicated in cadmium tolerance. In strain EGD-e, which harbors a chromosomal cadA3C cassette, cadC was markedly induced (10, 5, and 5-fold over 24, 48, and 72 h, respectively) in the livers of infected mice and was also required for normal virulence levels in a murine intravenous infection model (16).

Further evidence for a role of cadA4 in virulence modulation was obtained from a fitness assessment following the coinfection of larvae with a 1:1 mixture of F8027 and I1A2. The parental strain accounted for most (98%) of the L. monocytogenes population in larvae surviving on day 10 postinfection. Such findings suggest that cadA4 may function as a virulence modulator, with the possibility that cadA4-harboring L. monocytogenes is more prone to be tolerated as a commensal microbe rather than acting as a frank pathogen.

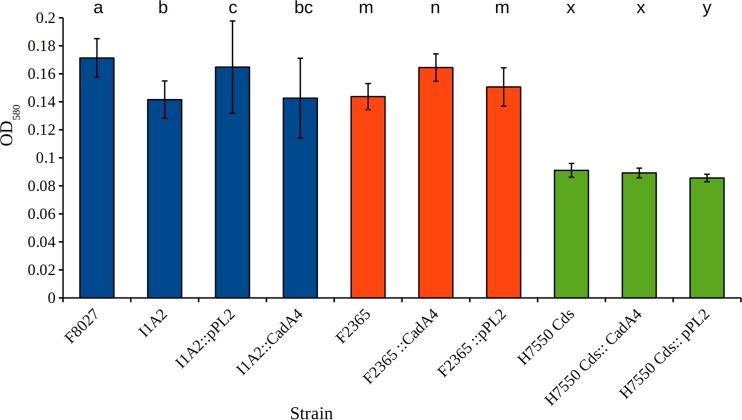

cadA4 inactivation reduces biofilm formation at 25°C.

Biofilm formation is critical to the ability of L. monocytogenes to persist on abiotic surfaces and, thus, is of direct relevance to food safety. The assessments of biofilm formation by F8027 and the cadA4 mutant I1A2 on 96-well polystyrene plates indicated that the two strains produced similar amounts of biofilm at 37°C (data not shown). However, at 25°C, biofilm formation by I1A2 was reduced in comparison to its parental counterpart according to the paired Student's t test (P <0.001) and with the nonparametric Wilcoxon comparison (P = 0.0416) (Fig. 9). The results from complemented I1A2 were not significantly different from those of I1A2 or I1A2 harboring pPL2 alone (Fig. 9), possibly reflecting the presence of two functional cadC copies, similar to the virulence findings described above. When heterologously expressed constructs were tested in strains F2365 and H7550-Cds, F2365 produced more biofilm than the parental strain (P <0.001) and the parental strain with the empty vector (P = 0.01) when analyzed with the paired Student's t test, but not when analyzed with nonparametric tests (P = 0.1039 and 0.8073, respectively) (Fig. 9), while biofilm formation was not impacted in H7550-Cds expressing the construct (Fig. 9). These data suggest a strain-dependent role of cadA4 in biofilm formation at 25°C, which may impact the ecology of L. monocytogenes not only in food processing plants but also in natural environments.

FIG 9.

Impact of cadA4 on biofilm formation. Biofilms were established in wells of 96-well plates (15 wells/strain) and measured following staining with crystal violet, as described in Materials and Methods. Differing letters within each group indicate statistically significant differences determined by comparison via paired Student's t test (P < 0.05). Error bars represent standard errors. Strains were as described in the legend of Fig. 4 and in Table 2.

cadA4 inactivation does not impact survival or growth of L. monocytogenes F8027 on produce.

F8027 was originally derived from raw celery and has been used in several studies related to L. monocytogenes adherence and growth on produce (21, 29, 30). However, special attributes potentially associated with the produce colonization potential of this strain remain unidentified. Therefore, we were interested in determining the potential involvement of strain-specific attributes, such as cadmium tolerance, in the ability of F8027 to colonize fresh produce. Furthermore, we wished to determine whether the impaired biofilm formation of I1A2 observed at 25°C might also result in impaired growth on produce. However, adherence and growth assessments on celery fragments at 25°C failed to identify significant differences between I1A2 and F8027. The two strains exhibited similar levels of adherence (approximately 10%) and growth on the surfaces of celery fragments, with ca. 1.4- and 2-log increases after 24 and 48 h, respectively (data not shown). The colonization of a cantaloupe rind also failed to reveal differences between the strains (data not shown). Taken together, the findings suggest that, under the tested conditions, cadA4 was not required for produce colonization.

The reasons for the lack of observed correspondence between the biofilm assay data at 25°C and produce colonization remain unidentified, but may include differences in the surfaces involved (polystyrene versus the biotic surface of living plant tissue) and in the presence of other microbiota. For instance, L. monocytogenes and Salmonella enterica can bind to cellulose-derived polymers (31), and lcp, which encodes a Listeria cellulose-binding protein, has been implicated in the adherence of L. monocytogenes F2365 to fresh produce (32).

Concluding remarks and perspectives.

In addition to the previously identified plasmid-borne cadA1C and cadA2C and the chromosomal cadA3C, we have confirmed the involvement of a fourth cadAC cassette, cadA4C, harbored chromosomally in Scott A and in the produce-derived strain F8027, in cadmium detoxification. Additional work is needed to further characterize the evolution and other potential fitness impacts of cadA4C. Assessments of virulence in Galleria mellonella suggest that cadA4 may serve to repress virulence. While possible impacts in other animal models remain to be determined, it is tempting to speculate that this virulence modulation may accompany the commensal persistence of cadA4-harboring strains in insect hosts. This may contribute to an amplification of L. monocytogenes in invertebrate reservoirs, which are currently poorly characterized but may play important roles in the natural ecology of L. monocytogenes. L. monocytogenes is present as a presumed saprophyte in soil (33), which also harbors a rich assortment of invertebrates, including the larvae of insects that may serve as hosts and reservoirs. This, together with the observed impact of cadA4C in biofilm formation at environmental (25°C) temperatures, reinforces the concept that the functionality of this cadmium resistance determinant is wider than just conferring tolerance to cadmium. The potential of these adaptations to impact the colonization of food processing environments and virulence warrants further studies to elucidate the roles of cadA4C in L. monocytogenes. Since cadA4C is harbored by numerous strains of L. monocytogenes in addition to Scott A, the F8027 strain investigated here, and several other bacterial pathogens previously mentioned, a better understanding of this resistance cassette could have far-reaching impacts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 2. Unless otherwise specified, L. monocytogenes was grown in brain heart infusion (BHI) (Becton, Dickinson & Co., Sparks, MD, USA) at 37°C. Erythromycin (5 μg/ml), kanamycin (10 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (8 μg/ml), or ciprofloxacin (0.05 μg/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were added as indicated. Escherichia coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) (Becton, Dickinson & Co.) broth or agar medium supplemented with chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml). A BioTek Elx808 absorbance microplate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA) was used for monitoring the growth of selected strains in the presence or absence of cadmium (0.1, 1.6, 5, and 10 μg/ml anhydrous CdCl2 [Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ, USA]). The changes in optical density (at 630 nm) were recorded and used to plot growth curves for each strain.

Heavy metal resistance and MIC determinations.

The agar dilution method was used for MICs, unless otherwise specified. Tolerances to cadmium chloride, sodium arsenate dibasic heptahydrate (Sigma), and sodium arsenite (Sigma) were assessed on Iso-Sensitest agar (ISA) (Oxoid, Hampshire, England) as previously described (12). In brief, single colonies (approximately 1 to 2 mm in diameter) were resuspended in 100 μl sterile water, and cell suspensions (4 μl) were spotted in duplicates at increasing concentrations (2.5, 5, 10, 15, 25, 35, 70, and 140 μg/ml cadmium chloride, 500 to 4,000 μg/ml sodium arsenate, and 50 to 1,000 μg/ml sodium arsenite). The MIC was designated the lowest concentration that prevented visible growth following an incubation at 37°C for 48 h. Copper (II) sulfate pentahydrate (Acros Organics, NJ, USA) and zinc sulfate hydrate (Alfa Aesar, Heysham, England) MICs were determined in BHI (5 to 12.5 mM copper sulfate and 1 to 30 mM zinc sulfate). MICs were determined in at least two independent trials. MICs for a panel of antibiotics (ampicillin, penicillin, oxacillin, pirlimycin, penicillin mixed with novobiocin, tetracycline, erythromycin, cephalothin, ceftiofur, and sulfadimethoxine) were kindly determined by M. Jacob, North Carolina State University School of Veterinary Medicine Clinical Microbiology Laboratory, via absorbance readings at 600 nm (A600) after 48 and 72 h in Mueller-Hinton broth. The efflux inhibitor reserpine (Sigma-Aldrich) was used at 40 μg/ml. MICs in the presence of reserpine were determined in duplicate experiments and in two independent trials, with MICs in the absence of reserpine used as controls.

Sequencing of cadAC cassette.

Primer pairs were designed based on the genome sequence of strain Scott A (19) to amplify five overlapping regions of cadAC from F8027. The PCR products were gel purified (QIAquick gel extraction kit; Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and sequenced at the North Carolina State University's genomic sciences laboratory. Nucleotide and deduced polypeptide sequences were aligned using Clustal W2 (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/) (34) and the alignments were used to compare the four known L. monocytogenes CadA sequences (CadA1 to CadA4). The Softberry BPROM software (http://www.softberry.com/berry.phtml?topic=bprom&group=programs&subgroup=gfindb) identified putative promoter sequences, and mFold (http://mfold.rna.albany.edu/?q=mfold) (35) identified inverted repeat sequences in the intergenic region upstream of cadAC, indicative of putative repressor binding sites.

RNA extraction and transcriptional assessments.

L. monocytogenes F8027 was grown in BHI at 25 and 37°C until mid to late logarithmic phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of 0.7 to 1.0, as measured by SmartSpec 3000; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). The culture was then divided into two portions, one of which was exposed to sublethal levels of cadmium (0.1, 1.6, or 5 μg/ml) and incubated for an additional 30 min at 25 or 37°C, while the other portion was similarly incubated without the addition of cadmium. RNA was extracted using the SV total RNA isolation system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and purified with Turbo DNA-free DNase (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) to remove any contaminating DNA. For RT-PCR, RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA with the ImProm-II reverse transcription system (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol, using either primer P4 (cadA4) or P21 (spoVG) (Table 1); spoVG was used as reference gene for each trial, as previously described (36). PCR was then performed with cDNA as the template using primers P3/P4 to assess cadA4 transcription and primers P16/P19 and P19/P18 to assess cotranscription of cadA4 with LMOSA _2320 and cadC, respectively. Negative controls (RNA and primers without reverse transcriptase) were included each time. For quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR), the Bio-Rad iTaq Universal SYBR green one-step kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) was used, per the manufacturer's instructions with a LightCycler 96 system (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Primers P22 to P29 (Table 1) were designed using Primer3Plus (http://primer3plus.com/) to measure the expression of cadA4, cadC, and LMOSA_2320, with spoVG used as a control. All experiments were repeated in at least three independent trials. Fold change calculations were carried out using the ΔΔCT method, normalizing for the expression of spoVG as described previously (36, 37).

Identification of cadmium-susceptible mutants and determination of transposon copy number and insertion in cadA4.

A mariner-based transposon mutant library of L. monocytogenes strain F8027 was constructed using pMC38 (38). The mutants were grown in individual wells of 96-well plates and screened in groups of 48 using a replicating device as described previously (36, 39) to identify those that failed to grow on ISA supplemented with cadmium (35 μg/ml). The number of transposon copies in the cadmium-susceptible mutants was determined using Southern blots as previously described (38, 39). To determine whether the transposon was inserted in cadA4, PCR was performed using the cadA4-targeting primers P3 and P4 (Table 1, Fig. 2), and the sizes of the resulting PCR products were determined by electrophoresis. To identify the transposon insertion site, two rounds of PCR were employed as described previously (38), followed by sequencing (Genewiz, Inc., South Plainfield, NJ, USA). The sequencing data were aligned using Clustal Omega (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/) (40), and sequences were analyzed with BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) (41) to differentiate the transposon from flanking chromosomal sequences.

Genetic complementation.

Primers P1 and P2 (Table 1) were designed with restriction sites for XmaI and SacI, respectively, and used to amplify a DNA fragment that included 333 nt of the intergenic region upstream of cadC (LMOSA_2321), harboring the putative promoter, as well as the coding sequences for cadC and cadA4. The PCR product was digested with XmaI and SacI (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA, USA), gel purified, and ligated using T4 DNA ligase (Promega) to similarly digested shuttle vector pPL2 (42), yielding the recombinant plasmid pPL2_cadA4. This plasmid was electroporated into E. coli S17-1 (43) resulting in E. coli S17-1_pPL_cadA4, and transferred into the cadA4 transposon mutant I1A2 via conjugation as described previously (39), yielding strain I1A2::cadA4. The plasmid was additionally transferred via conjugation to cadmium-susceptible L. monocytogenes strains F2365 and H7550-Cds, yielding F2365::cadA4 and H7550-Cds::cadA4, respectively (Table 2). I1A2, F2365, and H7550-Cds were also transformed with the empty vector pPL2, yielding I1A2::pPL2, F2365::pPL2 and H7550-Cds::pPL2, respectively (Table 2). Putative transconjugants were selected on media containing chloramphenicol (8 μg/ml) and ciprofloxacin (0.05 μg/ml), since pPL2 confers chloramphenicol resistance and L. monocytogenes (but not E. coli S17-1) is naturally resistant to ciprofloxacin at this concentration (44). The chromosomal insertion site of pPL2 or pPL_cadA4 was confirmed via PCR with P11 and either P14 or P15 primers (Table 1).

Site-directed mutagenesis.

To convert the alanine residue (GCA codon) in the metal-binding site of the deduced CadA4 of F8027 to threonine (ACA, conserved in cadA1 to cadA3), primers P32 and P33 (Table 1) were designed and the corresponding cadAC region was then amplified by PCR in two segments (P1 and P33, P32 and P2). Both P32 and P33 incorporated the desired base change. The resulting PCR products were cleaned up, mixed 1:1, and used as the template for PCR with primers P1 and P2, generating a complete CadAC cassette identical to the above complementation, except for the presence of the desired substitution. The PCR product was sequenced to confirm the mutation and cloned into pPL2 yielding pPL_cadA4SDM, which was then integrated into the cadA4 transposon mutant I1A2 (Table 2) as described above.

Adherence and growth on produce.

Strains were grown at 37°C overnight in BHI, washed twice in an equivalent volume of sterile water, and diluted in sterile water as needed. Retail whole fresh celery (bunch) was purchased and maintained at 4°C until it was used, typically on the same day. Celery fragments (2 by 1 by 0.5 cm) were prepared by aseptically cutting individual celery stalks with a flame-sterilized knife and then placed in sterile petri dishes and stored at 4°C until use. To assess adherence, cell suspensions were spot-inoculated (25 μl) in a series of droplets on the fragments and allowed to dry for 1 h at room temperature in a laminar flow cabinet. Each inoculated fragment was then placed in a sterile microcentrifuge tube containing 1 ml sterile water and gently rinsed by manually inverting the tube four times to remove loosely adherent cells. The fragment was then aseptically removed, placed in a new tube with 1 ml sterile water, and vortexed for 1 min to remove tightly adherent cells. Listeria organisms in the water were enumerated by plating appropriate dilutions on selective media (modified oxford agar [MOX]; Becton, Dickinson & Co.) and incubating at 37°C for 48 h. For assessing listerial growth on celery, fragments were dip-inoculated in a cell suspension of approximately 105 CFU/ml, air dried in the laminar flow cabinet for 1 h, and incubated at 25°C for up to 48 h. At 5, 24, and 48 h postinoculation, the fragments were vortexed in sterile water and suspensions plated on MOX for enumeration. Adherence and growth assays were performed in duplicate and in at least three independent trials.

Virulence assessments in Galleria mellonella.

Live fourth-instar larvae of the greater wax moth Galleria mellonella were purchased (Vanderhorst Wholesale, Inc., Saint Mary's, OH, USA), kept in their original shipping containers at room temperature in the dark, and used within 5 to 7 days. L. monocytogenes cell suspensions were prepared as described above for the inoculation of produce and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). For inoculations, 10 μl of cell suspension (106 CFU in PBS) were spotted as a droplet on the interior of the lid of a sterile petri dish. The droplet was picked up with a sterile 1-ml syringe and 30-G needle (Becton, Dickinson & Co.) and injected into the last left proleg of each larva. All procedures were performed in a biosafety cabinet. Ten larvae were inoculated per strain, and 10 control larvae were injected with the equivalent volumes of sterile PBS. Larvae were incubated at 37°C for up to 7 days. Larval death was monitored daily and based on a lack of movement in response to touch, and dead larvae were promptly removed. At the completion of the study, the remaining living larvae were euthanized by placing them at −20°C for 20 min. Virulence assessments were conducted in at least three independent trials. For competitive fitness trials, larvae were inoculated with 105 CFU/larva of 1:1 mixtures of I1A2 and F8027 in PBS. After 10 days, surviving larvae were crushed in 3 ml sterile water with a sterile glass rod and vortexed for 1 min. The resulting suspension was diluted and plated on MOX. Colonies (n = 96) were then tested on media with and without erythromycin, and strain ratios were determined.

Assessment of biofilm formation.

Biofilm formation was assessed in 96-well polystyrene plates (no. 655-185; Greiner Bio-One, VWR, Suwanee, GA) as described previously (45). Overnight cultures were diluted 1:50 in tryptic soy broth (TSB; Becton, Dickinson and Co.) in individual wells, and the 96-well plates were incubated at either 25 or 37°C for 48 h. Plates were washed three times with sterile water, stained with 0.8% crystal violet (Acros Organics), destained with 95% ethanol, and monitored for absorbance at 580 nm in a Tecan Safire 96 -well microplate reader (Tecan, Crailsheim, Germany). Biofilm assessments were conducted in at least three independent trials.

Statistical analyses.

Fold-change calculations for qPCR experiments were performed with the ΔΔCT method, with statistical evaluation of CT values using a paired Student's t test. For the statistical analysis of growth and adherence on produce, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Tukey's test was used with significance set at a P value of <0.05, with SPSS version 22 (IBM Corporation Software Group, Somers, NY, USA). For virulence data, the percent survivals of the Galleria larvae were averaged for at least three independent trials, and significance was determined using a paired Student's t test at a P value of <0.05. Larval survival data were also analyzed using a nonparametric proportional hazards survival model in JMP (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) to test for significant differences in survival of Galleria mellonella when inoculated with different strains of L. monocytogenes. All strains were analyzed in a pairwise fashion to determine significance (at a P value of <0.05). Biofilm data were analyzed using a paired Student's t tests (significance at P values of <0.05) and also analyzed using the nonparametric Wilcoxon method for each pair (significance at P values of <0.05).

Accession number(s).

The sequence of L. monocytogenes F8027 cadA4C was deposited in NCBI under accession number KT946835.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was partially funded by a USDA grant (no. 2011-2012-67017-30218).

We thank all of the members of our laboratory for their support. We thank P. Brown for assistance with biofilm assays, F. Breidt and I. Perez-Diaz for access to equipment utilized in certain components of the study, R. M. Siletzky and S. Ratani for their advice and guidance in earlier portions of the study, D. Elhanafi for his feedback and support, and A. Parsons for statistical advice and reviews of early drafts of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vivant A-L, Garmyn D, Piveteau P. 2013. Listeria monocytogenes, a down-to-earth pathogen. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 3:87. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scallan E, Hoekstra RM, Angulo FJ, Tauxe RV, Widdowson MA, Roy SL, Jones JL, Griffin PM. 2011. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States–major pathogens. Emerg Infect Dis 17:7–15. doi: 10.3201/eid1701.P11101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dutta V, Elhanafi D, Osborne J, Martinez MR, Kathariou S. 2014. Genetic characterization of plasmid-associated triphenylmethane reductase in Listeria monocytogenes. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:5379–5385. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01398-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lebrun M, Audurier A, Cossart P. 1994. Plasmid-borne cadmium resistance genes in Listeria monocytogenes are similar to cadA and cadC of Staphylococcus aureus and are induced by cadmium. J Bacteriol 176:3040–3048. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.10.3040-3048.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gandhi M, Chikindas ML. 2007. Listeria: a foodborne pathogen that knows how to survive. Int J Food Microbiol 113:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romanova N, Favrin S, Griffiths MW. 2002. Sensitivity of Listeria monocytogenes to sanitizers used in the meat processing industry. Appl Environ Microbiol 68:6405–6409. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.12.6405-6409.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alam MZ, Ahmad S, Malik A. 2011. Prevalence of heavy metal resistance in bacteria isolated from tannery effluents and affected soil. Environ Monit Assess 178:281–291. doi: 10.1007/s10661-010-1689-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee S, Ward TJ, Graves LM, Tarr CL, Siletzky RM, Kathariou S. 2014. Population structure of Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b isolates from sporadic human listeriosis in the United States, 2003–2008. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:3632–3644. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00454-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harvey J, Gilmour A. 2001. Characterization of recurrent and sporadic Listeria monocytogenes isolates from raw milk and nondairy foods by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, monocin typing, plasmid profiling, and cadmium and antibiotic resistance determination. Appl Environ Microbiol 67:840–847. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.2.840-847.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lebrun M, Audurier A, Cossart P. 1994. Plasmid-borne cadmium resistance genes in Listeria monocytogenes are present on Tn5422, a novel transposon closely related to Tn917. J Bacteriol 176:3049–3061. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.10.3049-3061.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee S, Rakic-Martinez M, Graves LM, Ward TJ, Siletzky RM, Kathariou S. 2013. Genetic determinants for cadmium and arsenic resistance among Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b isolates from sporadic human listeriosis patients. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:2471–2476. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03551-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mullapudi S, Siletzky RM, Kathariou S. 2010. Diverse cadmium resistance determinants in Listeria monocytogenes isolates from the turkey processing plant environment. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:627–630. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01751-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuenne C, Voget S, Pischimarov J, Oehm S, Goesmann A, Daniel R, Hain T, Chakraborty T. 2010. Comparative analysis of plasmids in the genus Listeria. PLoS One 5:pii:e12511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuenne C, Billion A, Mraheil MA, Strittmatter A, Daniel R, Goesmann A, Barbuddhe S, Hain T, Chakraborty T. 2013. Reassessment of the Listeria monocytogenes pan-genome reveals dynamic integration hotspots and mobile genetic elements as major components of the accessory genome. BMC Genomics 14:47. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glaser P, Frangeul L, Buchrieser C, Rusniok C, Amend A, Baquero F, Berche P, Bloecker H, Brandt P, Chakraborty T, Charbit A, Chetouani F, Couve E, de Daruvar A, Dehoux P, Domann E, Dominguez-Bernal G, Duchaud E, Durant L, Dussurget O, Entian KD, Fsihi H, Garcia-del Portillo F, Garrido P, Gautier L, Goebel W, Gomez-Lopez N, Hain T, Hauf J, Jackson D, Jones LM, Kaerst U, Kreft J, Kuhn M, Kunst F, Kurapkat G, Madueno E, Maitournam A, Vicente JM, Ng E, Nedjari H, Nordsiek G, Novella S, de Pablos B, Perez-Diaz JC, Purcell R, Remmel B, Rose M, Schlueter T, Simoes N, Tierrez A, Vazquez-Boland JA, Voss H, Wehland J, Cossart P. 2001. Comparative genomics of Listeria species. Science 294:849–852. doi: 10.1126/science.1063447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Camejo A, Buchrieser C, Couvé E, Carvalho F, Reis O, Ferreira P, Sousa S, Cossart P, Cabanes D. 2009. In vivo transcriptional profiling of Listeria monocytogenes and mutagenesis identify new virulence factors involved in infection. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000449. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLaughlin HP, Xiao Q, Rea RB, Pi H, Casey PG, Darby T, Charbit A, Sleator RD, Joyce SA, Cowart RE, Hill C, Klebba PE, Gahan CG. 2012. A putative P-type ATPase required for virulence and resistance to haem toxicity in Listeria monocytogenes. PLoS One 7:e30928. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho JL, Shands KN, Friedland G, Eckind P, Fraser DW. 1986. An outbreak of type 4b Listeria monocytogenes infection involving patients from eight Boston hospitals. Arch Intern Med 146:520–524. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1986.00360150134016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Briers Y, Klumpp J, Schuppler M, Loessner MJ. 2011. Genome sequence of Listeria monocytogenes Scott A, a clinical isolate from a food-borne listeriosis outbreak. J Bacteriol 193:4284–4285. doi: 10.1128/JB.05328-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Y, Strain EA, Allard M, Brown EW. 2011. Genome sequences of Listeria monocytogenes strains J1816 and J1-220, associated with human outbreaks. J Bacteriol 193:3424–3425. doi: 10.1128/JB.05048-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lang MM, Harris LJ, Beuchat LR. 2004. Evaluation of inoculation method and inoculum drying time for their effects on survival and efficiency of recovery of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella, and Listeria monocytogenes inoculated on the surface of tomatoes. J Food Prot 67:732–741. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-67.4.732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McLauchlin J, Hampton MD, Shah S, Threlfall EJ, Wieneke AA, Curtis GD. 1997. Subtyping of Listeria monocytogenes on the basis of plasmid profiles and arsenic and cadmium susceptibility. J Appl Microbiol 83:381–388. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1997.00238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu D, Li Y, Zahid MS, Yamasaki S, Shi L, Li JR, Yan H. 2014. Benzalkonium chloride and heavy-metal tolerance in Listeria monocytogenes from retail foods. Int J Food Microbiol 190:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2014.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelson KE, Fouts DE, Mongodin EF, Ravel J, DeBoy RT, Kolonay JF, Rasko DA, Angiuoli SV, Gill SR, Paulsen IT, Peterson J, White O, Nelson WC, Nierman W, Beanan MJ, Brinkac LM, Daugherty SC, Dodson RJ, Durkin AS, Madupu R, Haft DH, Selengut J, Van Aken S, Khouri H, Fedorova N, Forberger H, Tran B, Kathariou S, Wonderling LD, Uhlich G, Bayles DO, Luchansky JB, Fraser CM. 2004. Whole genome comparisons of serotype 4b and 1/2a strains of the food-borne pathogen Listeria monocytogenes reveal new insights into the core genome components of this species. Nucleic Acids Res 32:2386–2395. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bal N, Wu CC, Catty P, Guillain F, Mintz E. 2003. Cd2+ and the N-terminal metal-binding domain protect the putative membranous CPC motif of the Cd2+-ATPase of Listeria monocytogenes. Biochem J 369:681–685. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elhanafi D, Dutta V, Kathariou S. 2010. Genetic characterization of plasmid-associated benzalkonium chloride resistance determinants in a Listeria monocytogenes strain from the 1998–1999 outbreak. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:8231–8238. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02056-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.United Nations Environment Programme, Chemicals Branch DTIE. 2010. Final review of scientific information on cadmium, version of December 2010. http://www.unep.org/hazardoussubstances/Portals/9/Lead_Cadmium/docs/Interim_reviews/UNEP_GC26_INF_11_Add_2_Final_UNEP_Cadmium_review_and_apppendix_Dec_2010.pdf Accessed 2 September 2016.

- 28.Schrama D, Helliwell N, Neto L, Faleiro ML. 2013. Adaptation of Listeria monocytogenes in a simulated cheese medium: effects on virulence using the Galleria mellonella infection model. Lett Appl Microbiol 56:421–427. doi: 10.1111/lam.12064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lang MM, Harris LJ, Beuchat LR. 2004. Survival and recovery of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella, and Listeria monocytogenes on lettuce and parsley as affected by method of inoculation, time between inoculation and analysis, and treatment with chlorinated water. J Food Prot 67:1092–1103. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-67.6.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beuchat LR, Adler BB, Lang MM. 2004. Efficacy of chlorine and a peroxyacetic acid sanitizer in killing Listeria monocytogenes on iceberg and Romaine lettuce using simulated commercial processing conditions. J Food Prot 67:1238–1242. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-67.6.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tan MSF, Wang Y, Dykes GA. 2013. Attachment of bacterial pathogens to a bacterial cellulose-derived plant cell wall model: a proof of concept. Foodborne Pathog Dis 10:992–994. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2013.1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bae D, Seo KS, Zhang T, Wang C. 2013. Characterization of a potential Listeria monocytogenes virulence factor associated with attachment to fresh produce. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:6855–6861. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01006-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gray ML, Killinger AH. 1966. Listeria monocytogenes and listeric infections. Bacteriol Rev 30:309–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. 2007. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zuker M. 2003. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res 31:3406–3415. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim J-W, Dutta V, Elhanafi D, Lee S, Osborne JA, Kathariou S. 2012. A novel restriction-modification system is responsible for temperature-dependent phage resistance in Listeria monocytogenes ECII. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:1995–2004. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07086-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bae D, Crowley MR, Wang C. 2011. Transcriptome analysis of Listeria monocytogenes grown on a ready-to-eat meat matrix. J Food Prot 74:1104–1111. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-10-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cao M, Bitar AP, Marquis H. 2007. A mariner-based transposition system for Listeria monocytogenes. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:2758–2761. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02844-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Azizoglu RO, Kathariou S. 2010. Temperature-dependent requirement for catalase in aerobic growth of Listeria monocytogenes F2365. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:6998–7003. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01223-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, Lopez R, McWilliam H, Remmert M, Söding J, Thompson JD, Higgins DG. 2011. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol 7:539. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lauer P, Chow MYN, Loessner MJ, Portnoy D, Calendar R. 2002. Construction, characterization, and use of two Listeria monocytogenes site-specific phage integration vectors. J Bacteriol 184:4177–4186. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.15.4177-4186.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simon R, Priefer U, Pühler A. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram negative bacteria. Nat Biotechnol 1:784–791. doi: 10.1038/nbt1183-784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stock I, Wiedemann B. 1999. Natural antibiotic susceptibility of Escherichia coli, Shigella, E. vulneris, and E. hermannii strains. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 33:187–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pan Y, Breidt F, Kathariou S. 2009. Competition of Listeria monocytogenes serotype 1/2a and 4b strains in mixed-culture biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:5846–5852. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00816-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]