Abstract

Gastric cancer screening using endoscopy has recently spread in Eastern Asian countries showing increasing evidence of its effectiveness. However, despite the benefits of endoscopic screening for gastric cancer, its major harms include infection, complications, false-negative results, false-positive results, and overdiagnosis. The most serious harm of endoscopic screening is overdiagnosis and this can occur in any cancer screening programs. Overdiagnosis is defined as the detection of cancers that would never have been found if there is no cancer screening. Overdiagnosis has been estimated from randomized controlled trials, observational studies, and modeling. It can be calculated on the basis of a comparison of the incidence of cancer between screened and unscreened individuals after the follow-up. Although the estimation method for overdiagnosis has not yet been standardized, estimation of overdiagnosis is needed in endoscopic screening for gastric cancer. To minimize overdiagnosis, the target age group and screening interval should be appropriately defined. Moreover, the balance of benefits and harms must be carefully considered to effectively introduce endoscopic screening in communities. Further research regarding overdiagnosis is warranted when evaluating the effectiveness of endoscopic screening.

Keywords: Gastric cancer, Cancer screening, Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, Overdiagnosis, Harm

Core tip: Overdiagnosis is the most serious harm of cancer screening and this can occur in any cancer screening programs. It is defined as the detection of cancers that would never have been found if there is no screening. Despite the lack of standardization of the estimation method for overdiagnosis, its estimation is necessary in endoscopic screening for gastric cancer. To minimize overdiagnosis, the target age group and screening interval should be appropriately defined. Consideration of the balance of benefits and harms of endoscopic screening is imperative for its effective introduction in communities.

INTRODUCTION

Endoscopic examination has been increasingly performed for gastric cancer screening in Eastern Asian countries[1]. Although national programs for gastric cancer screening have already been started in South Korea and Japan, endoscopic screening has been mainly performed in clinical settings as opportunistic screening[2]. Since 1999, endoscopic screening for gastric cancer has been performed in South Korea[3]. In 2016, the Japanese government decided to introduce endoscopic screening for gastric cancer as a national program based on the guidelines published by the National Cancer Center in Japan[4]. Although evidence for reduction in mortality from gastric cancer by endoscopic screening was insufficient when this method was initially introduced in South Korea, evidence regarding its effectiveness has gradually increased in South Korea, China, and Japan[5-8]. Gastric cancer screening by endoscopy has been increasingly anticipated because early stage cancer can be more definitively diagnosed than by radiographic screening using upper gastrointestinal series with barium meal.

Despite the benefits of endoscopic screening for gastric cancer, the major harms of this technique include infection, complications, false-negative results, false-positive results, and overdiagnosis[4]. Although complications and infection are highly probable in endoscopic screening, these can be minimized by appropriate safety management. On the other hand, false-positive results and overdiagnosis frequently occur in all cancer screenings. The false-positive rate can be managed using a quality assurance system to some extent[9]. However, because of the high sensitivity of endoscopic examination which can detect many early stage cancers, overdiagnosis cannot be avoided. To effectively introduce endoscopic screening in communities, the balance of benefits and harms should be prudently analyzed. Therefore, comprehensive knowledge of overdiagnosis in endoscopic screening is crucial as well as effective strategies for its management.

BASIC CONCEPT OF OVERDIAGNOSIS

When we consider the harms of endoscopic screening, overdiagnosis cannot be ignored because it occurs in this procedure and in all cancer screening programs[10]. Overdiagnosis represents the actual cancer detected by screening which would never have been found if there is no cancer screening. In cancer screening, it is not possible to distinguish between an overdiagnosis of cancer and a diagnosis of cancer that will progress[10]. Overdiagnosis leads to unnecessary examinations and treatments, the results of which can cause psychological problems[11].

Mammographic screening provides an easily understood example of the basic concept of overdiagnosis. Since the late 1990s, mammographic screening for breast cancer has rapidly spread nationwide in the United States. Women aged 40-69 years were the major target of mammographic screening. In Figure 1A, the upper graph shows a large impact of mammographic screening during the 1980s and early 1990s among women aged 40 years or older in the United States[12]. In the same Figure 1A, the lower graph shows a rapid increase in the incidence of early stage breast cancer according to the dissemination of mammographic screening. However, a small decrease in the incidence of late-stage breast cancer is observed.

Figure 1.

Trends of breast cancer incidence before and after mammographic screenings in the United States. A: Use of mammographic screening and incidence of stage-specific breast cancer among women 40 years of age and older; B: Incidence of stage-specific breast cancer among women younger than 40 years of age[12].

In Figure 1B, breast cancer incidence flattened in women younger than 40 years of age because they did not have any opportunity to have mammographic screening. These trends of breast cancer in women aged 40 years and over suggested that the detected early stage cancer included cases of overdiagnosis.

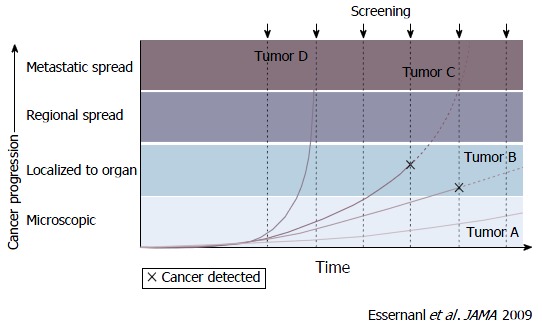

There have also been developments of new techniques which can diagnose cancers that do not progress and are not fatal even if left untreated. The growth rates of cancer vary and are divided into 4 categories: Rapid, slow, very slow, and non-progressive. Periodic screening detects slow-growing (Tumor B) and non-progressive (Tumor A) cancers early, and finds some progressive cancer (Tumor C) early (Figure 2)[13]. Without screening, Tumor A remains undetectable and causes no morbidity during the patient’s lifetime. However, rapid-growing cancer (Tumor D) which is a fatal tumor cannot be screened earlier and may cause death even with treatment. The benefit of screening is limited to true-positive results when earlier treatment works better. Even if the screening result is true-positive, there are no benefits for Tumors A, D and partly C[13]. When screening starts, this screening cascade cannot be stopped[14].

Figure 2.

Screen detection capability based on tumor biology and growth rates[13]. The growth rates of cancer vary and are divided into 4 categories: Rapid, slow, very slow, and non-progressive. Periodic screening detects slow-growing (Tumor B) and non-progressive (Tumor A) cancers early, and finds some progressive cancer (Tumor C) early. Tumor A remains undetectable and causes no morbidity during the patients’ lifetime without screening. However, rapid-growing cancer (Tumor D) which is a fatal tumor is not screened earlier and can cause death even with treatment.

Overdiagnosis is not limited to the harms of cancer screening and it can occur in any diagnostic examinations. However, the frequency of overdiagnosis varies among examinations and diseases. The target of cancer screening is asymptomatic persons without any health problems. Therefore, in cancer screening, harms should be minimized and benefits should outweigh harms[14]. Importantly, the harms of cancer screening are often ignored because the screening benefits are usually emphasized. Although there is a possibility that endoscopic screening has made a large impact in terms of reducing mortality from gastric cancer, we have to consider minimizing its harms, particularly overdiagnosis. Therefore, estimation of the frequency of overdiagnosis is a key issue in considering the balance of benefits and harms of endoscopic screening.

ESTIMATION OF OVERDIAGNOSIS

Overdiagnosis has been estimated from randomized controlled trials (RCTs), ecological and cohort studies, pathological and imaging studies, and modeling[15]. The frequency of overdiagnosis is calculated on the basis of the difference in the incidence of cancer between screened and unscreened individuals after the follow-up. Although the estimation method has not yet been standardized, there is a high divergence, for example, 0%-50% in mammographic screening[16].

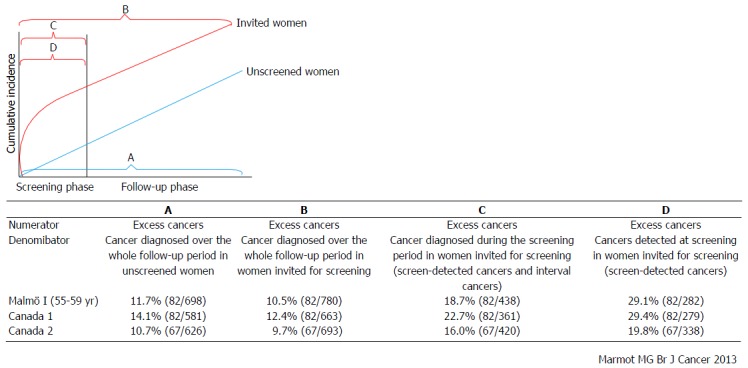

The frequency of overdiagnosis was previously estimated on the basis of RCTs without the provision of mammographic screening at the end of the screening phases. In the Independent United Kingdom Panel on Breast Cancer Screening, the overdiagnosis rate was calculated from the Canadian and Malmo studies for mammographic screening using 4 methods with different denominators as follows (Figure 3)[16]: (1) excess cancers as the frequency of cancers diagnosed over the whole follow-up period in unscreened women; (2) excess cancers as the frequency of cancers diagnosed over the whole follow-up period in women invited for screening; (3) excess cancers as the frequency of cancers diagnosed during the screening period in women invited for screening; and (4) excess cancers as the frequency of cancers detected at screening in women invited for screening. The frequency of overdiagnosis was estimated to be higher when the follow-up periods were limited to the screening phases. In the conclusions, the overdiagnosis rate for mammographic screening was in the range of 10%-20% based on the estimation using the data from 2 RCTs. Recently, a Canadian study has reported an overdiagnosis frequency of 22% based on 25 years of follow-up[17].

Figure 3.

Estimation of frequency of overdiagnosis on the basis of the results of Malmö and Canadian studies. The frequency of overdiagnosis was calculated on the basis of 2 randomized controlled trials for mammographic screening using 4 methods with different denominators as follows: A: Excess cancers as the frequency of cancers diagnosed over the whole follow-up period in unscreened women; B: Excess cancers as the frequency of cancers diagnosed over the whole follow-up period in women invited for screening; C: Excess cancers as the frequency of cancers diagnosed during the screening period in women invited for screening; D: Excess cancers as the frequency of cancers detected at screening in women invited for screening[16].

On the other hand, ecological and cohort studies have been commonly used to estimate the frequency of overdiagnosis. These studies can directly answer questions in real world settings and compare results from different settings[15]. Carter et al[15] have suggested that ecological and cohort studies in multiple settings are the most appropriate approaches for qualifying and monitoring overdiagnosis in cancer screening programs.

OVERDIAGNOSIS OF GASTRIC CANCER BY ENDOSCOPIC SCREENING

The frequency of overdiagnosis of gastric cancer by endoscopic screening has not yet been estimated. Excess rate was calculated on the basis of the results of endoscopic screening for gastric cancer which indicated that the observed number of detected cancer was twice the expected number (Table 1)[18]. However, the excess cancers included both early detection cases which progress into fatal cancers and overdignosis cases.

Table 1.

Comparison of results from cohort studies of endoscopic screening for gastric cancer

| Target for cancer screening | Method |

Male |

Female |

||||

| Observed number | Expected number | O/E | Observed number | Expected number | O/E | ||

| Stomach | Endoscopy | 28 | 15.31 | 1.83 | 7 | 3.69 | 1.9 |

| Colon and rectum | Barium enema | 4 | 2.25 | 1.78 | 4 | 1.08 | 3.7 |

| Total colonoscopy | 26 | 21.9 | 1.19 | 15 | 7.64 | 1.96 | |

| Lung | CT | 14 | 10.86 | 1.29 | 18 | 2.38 | 7.56 |

| Prostate | PSA | 24 | 7 | 3.43 | - | - | - |

| Breast | Combination of mammography, ultrasonography and physical examination | - | - | - | 15 | 6.22 | 2.41 |

Available from Hamashima et al[18], 2006. O: Observed number; E: Expected number; CT: Computed tomography; PSA: Prostate specific antigen.

The calculation of sensitivity is affected by the number of overdiagnosis cases. The detection method is the most common and simplest procedure for calculating sensitivity in which the numerator includes all detected cancers and the denominator is the sum of detected cancers and interval cancers. In the detection method, sensitivity is often overestimated, whereas in the incidence method, overdiagnosis cases can be avoided[19]. Sensitivity calculation by the incidence method was adopted in breast, lung, and colorectal cancer screenings[20-22]. In prevalence screening for using endoscopic screening for gastric cancer, the sensitivity was reportedly 0.955 (95%CI: 0.875-0.991) by the detection method and 0.886 (95%CI: 0.698-0.976) by the incidence method (Table 2)[23]. In incidence screening using endoscopic screening for gastric cancer, the sensitivity was reportedly 0.977 (95%CI: 0.919-0.997) by the detection method and 0.954 (95%CI: 0.842-0.994) by the incidence method[23]. The discrepancy between the results calculated by the detection method and the incidence method was small. It might be suggested that the frequency of overdiagnosis on endoscopic screening for gastric cancer is not very high.

Table 2.

Sensitivities and specificities of endoscopy and radiography for gastric cancer screening

| Screening round | Method |

Sensitivity |

Specificity |

Sensitivity |

| By the detection method | By the detection method | By the incidence method | ||

| Prevalence screening | Endoscopic screening | 0.955 (95%CI: 0.875-0.991) | 0.851 (95%CI: 0.843-0.859) | 0.886 (95%CI: 0.698-0.976) |

| Radiographic screening | 0.893 (95%CI: 0.718-0.977) | 0.856 (95%CI: 0.846-0.865) | 0.831 (95%CI: 0.586-0.964) | |

| Incidence screening | Endoscopic screening | 0.977 (95%CI: 0.919-0.997) | 0.888 (95%CI: 0.883-0.892) | 0.954 (95%CI: 0.842-0.994) |

| Radiographic screening | 0.885 (95%CI: 0.664-0.972) | 0.891 (95%CI: 0.885-0.896) | 0.855 (95%CI: 0.637-0.970) |

Available from Hamashima et al[23], 2013.

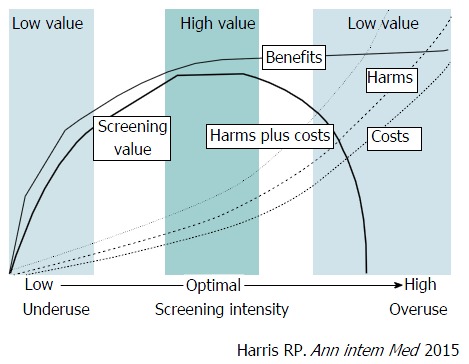

STRATEGIES FOR MANAGEMENT OF OVERDIAGNOSIS

Although frequent screenings can diagnose numerous cancers, the possibility of including overdiagnosis is high. In actuality, frequent screenings easily result in overdiagonsis. Therefore, the appropriate number of screenings should be considered in endoscopic screening for gastric cancer. The American College of Physicians has recommended high-value care based on the value framework (Figure 4)[14,24]. The value of cancer screening is determined by a trade-off between benefits vs harms and costs. As the intensity increases, the benefits of screening rapidly increase. However, as the intensity increases beyond an optimal level, the benefits decrease whereas the harms and costs increase rapidly thereby reducing the value of cancer screening. High-value care has been recommended which is defined as the lowest intensity threshold. On the basis of this concept, high-value and low-value screening strategies have been developed for 5 types of cancer. This framework can be adopted in endoscopic screening for gastric cancer. Since endoscopic screening has a high sensitivity, it has the same problems. To minimize harms including overdiagnosis and to maximize the benefits, the target age group and screening interval should be appropriately clarified. To decrease the harms of unnecessary examinations and treatments, the “Choosing Wisely” campaign has rapidly expanded collaboration with academic societies in the United States and other countries[25]. The basic concepts of the “Choosing Wisely” campaign are focused on the same goal of minimization of unnecessary examinations and treatments.

Figure 4.

A value framework for cancer screening. The value of cancer screening strategies is linked to the screening intensity (population screened, frequency, and sensitivity of the test used) and is determined by the balance among benefits (e.g., cancer mortality reduction), harms (e.g., anxiety from false-positive test results, harms of diagnostic procedures, labeling, and overdiagnosis leading to overtreatment), and costs. The value of cancer screening is determined by a trade-off between benefits vs harms and costs. As the intensity increases, the benefits of screening rapidly increase. However, as the intensity increases beyond an optimal level, the increase in benefits slows down whereas harms and costs increase rapidly, and the value decreases[14].

CONCLUSION

Overdiagnosis is the most serious harm of endoscopic screening for gastric cancer. Although the estimation method for the frequency of overdiagnosis has not yet been standardized, the present study is essential in further assessing the harms of endoscopic screening for gastric cancer in terms of overdiagnosis. To minimize overdiagnosis, the target age group and screening interval should be clearly defined in consideration of the balance of benefits and harms. Further research into overdiagnosis in endoscopic screening is warranted to realize its effective introduction in communities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are indebted to Dr. Edward F Barroga, Associate Professor and Senior Medical Editor of Tokyo Medical University for reviewing and editing the English manuscript. We also thank Ms. Kanoko Matsushima, Ms. Junko Asai, and Ms. Ikuko Tominaga for research assistance.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Conflict-of-interest statement: The author has no conflicts of interest to report.

Peer-review started: August 21, 2016

First decision: September 28, 2016

Article in press: December 9, 2016

P- Reviewer: Chrom P, El-Tawil AM, Soriano-Ursua MA S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

References

- 1.Leung WK, Wu MS, Kakugawa Y, Kim JJ, Yeoh KG, Goh KL, Wu KC, Wu DC, Sollano J, Kachintorn U, et al. Screening for gastric cancer in Asia: current evidence and practice. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:279–287. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70072-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goto R, Hamashima C, Mun S, Lee WC. Why screening rates vary between Korea and Japan--differences between two national healthcare systems. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:395–400. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.2.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim Y, Jun JK, Choi KS, Lee HY, Park EC. Overview of the National Cancer screening programme and the cancer screening status in Korea. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:725–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamashima C. Benefits and harms of endoscopic screening for gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:6385–6392. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i28.6385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamashima C, Shabana M, Okada K, Okamoto M, Osaki Y. Mortality reduction from gastric cancer by endoscopic and radiographic screening. Cancer Sci. 2015;106:1744–1749. doi: 10.1111/cas.12829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamashima C, Ogoshi K, Okamoto M, Shabana M, Kishimoto T, Fukao A. A community-based, case-control study evaluating mortality reduction from gastric cancer by endoscopic screening in Japan. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79088. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho B. Seoul: Seoul University; 2013. Evaluation of the validity of current national health screening programs and plans to improve the system; pp. 741–758 (in Korean). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Q, Yu L, Hao CQ, Wang JW, Liu SZ, Zhang M, Zhang SK, Guo LW, Quan PL, Zhao N, et al. Effectiveness of endoscopic gastric cancer screening in a rural area of Linzhou, China: results from a case-control study. Cancer Med. 2016;5:2615–2622. doi: 10.1002/cam4.812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamashima C, Fukao A. Quality assurance manual of endoscopic screening for gastric cancer in Japanese communities. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2016 doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyw106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vainio H, Bianchini F (eds.) Lyon: IARC Press; 2002. IARC Handbooks of Cancer Presentation. Volume 7. Breast Cancer Screening. ; pp. 144–147. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Black WC. Overdiagnosis: An underrecognized cause of confusion and harm in cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1280–1282. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.16.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bleyer A, Welch HG. Effect of screening mammography on breast cancer incidence. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:677–679. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1215494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Esserman L, Shieh Y, Thompson I. Rethinking screening for breast cancer and prostate cancer. JAMA. 2009;302:1685–1692. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris RP, Wilt TJ, Qaseem A. A value framework for cancer screening: advice for high-value care from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:712–717. doi: 10.7326/M14-2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carter JL, Coletti RJ, Harris RP. Quantifying and monitoring overdiagnosis in cancer screening: a systematic review of methods. BMJ. 2015;350:g7773. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marmot MG, Altman DG, Cameron DA, Dewar JA, Thompson SG, Wilcox M. The benefits and harms of breast cancer screening: an independent review. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:2205–2240. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller AB, Wall C, Baines CJ, Sun P, To T, Narod SA. Twenty five year follow-up for breast cancer incidence and mortality of the Canadian National Breast Screening Study: randomised screening trial. BMJ. 2014;348:g366. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamashima C, Sobue T, Muramatsu Y, Saito H, Moriyama N, Kakizoe T. Comparison of observed and expected numbers of detected cancers in the research center for cancer prevention and screening program. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2006;36:301–308. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyl022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Day NE. Estimating the sensitivity of a screening test. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1985;39:364–366. doi: 10.1136/jech.39.4.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fletcher SW, Black W, Harris R, Rimer BK, Shapiro S. Report of the International Workshop on Screening for Breast Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:1644–1656. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.20.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zappa M, Castiglione G, Paci E, Grazzini G, Rubeca T, Turco P, Crocetti E, Ciatto S. Measuring interval cancers in population-based screening using different assays of fecal occult blood testing: the District of Florence experience. Int J Cancer. 2001;92:151–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toyoda Y, Nakayama T, Kusunoki Y, Iso H, Suzuki T. Sensitivity and specificity of lung cancer screening using chest low-dose computed tomography. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:1602–1607. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamashima C, Okamoto M, Shabana M, Osaki Y, Kishimoto T. Sensitivity of endoscopic screening for gastric cancer by the incidence method. Int J Cancer. 2013;133:653–659. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilt TJ, Harris RP, Qaseem A. Screening for cancer: advice for high-value care from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:718–725. doi: 10.7326/M14-2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.ABIM Foundation. Choosing Wisely. Available from: http://www.choosingwisely.org/