Abstract

The multisubunit eukaryotic initiation factor 3 (eIF3) plays multiple roles in translation but is poorly understood in trypanosomes. The putative subunits eIF3a and eIF3f of Trypanosoma brucei (TbIF3a and TbIF3f) were overexpressed and purified, and 11 subunits were identified, TbIF3a through l minus j, which form a tight complex. Both TbIF3a and TbIF3f are essential for the viability of T. brucei. RNAi knockdown of either of them severely reduced total translation and the ratio of the polysome/80S peak area. TbIF3f and TbIF3a RNAi cell lines were modified to express tagged-TbIF3a and -TbIF3f, respectively. RNAi in combination with affinity purification assays indicated that both subunits are variably required for TbIF3 stability and integrity. The relative abundance of other subunits in the TbIF3f-tag complex changed little upon TbIF3a depletion; while only subunits TbIF3b, i, and e copurified comparably with TbIF3a-tag upon TbIF3f depletion. A genome-wide UV-crosslinking assay showed that several TbIF3 subunits have direct RNA-binding activity, with TbIF3c showing the strongest signal. In addition, CrPV IRES, but neither EMCV IRES nor HCV IRES, was found to mediate translation in T. brucei. These results together imply that the structure of TbIF3 and the subunits function have trypanosome-specific features, although the composition is evolutionarily conserved.

Keywords: translation, eukaryotic initiation factor 3, trypanosome

INTRODUCTION

Trypanosoma brucei, Trypanosoma cruzi, and Leishmania major can cause African sleeping sickness, American trypanosomiasis, and Leishmaniasis, respectively. They are unicellular protozoans and cycle between mammals and blood sucking insects. The proliferating forms of T. brucei in mammal blood and in tsetse fly intestine are designated bloodstream form (BF) and procyclic form (PF), respectively.

As anciently diverged organisms, trypanosomes possess many unique biological and metabolism features, such as tandem genes arrangement and polycistronic transcription (Opperdoes 1994; Martinez-Calvillo et al. 2004; Siegel et al. 2009). The production of mature mRNAs are through the coupled trans-splicing and polyadenylation (Matthews et al. 1994; Siegel et al. 2010). The resulted cap structure, named cap 4, is unusual and highly methylated in the first four nucleotides following the methylated guanosine (Bangs et al. 1992; Mair et al. 2000), whose full methylation is essential for maximized translation (Zamudio et al. 2009). Accordingly, the cap-binding translation initiation factor of trypanosomes, i.e., eIF4F, has unusual aspects as well, shown by an expanding number of subunit variants and a different combination (Dhalia et al. 2006; Freire et al. 2014; Moura et al. 2015). These unique features imply some trypanosome-specific translation patterns; however, little is known about the translation apparatus of trypanosomes, especially which one initiates translation.

Translation initiation is a complicated and highly ordered process and has been extensively studied in yeast and mammals. The largest translation initiation factor 3 (eIF3) plays multiple roles as a scaffold and a coordinator through the whole process (Hinnebusch 2006, 2014; Aitken and Lorsch 2012). Briefly, eIF3 mediates a multifactor complex eIF1–eIF1A–eIF3–eIF5 binding to a 40S ribosomal subunit and then recruits a ternary complex eIF2–GTP-Met-tRNAi to the 40S subunit (Sun et al. 2011; Sokabe et al. 2012). The resulting 43S preinitiation complex (PIC) attaches to the 5′-proximal region of an mRNA through eIF3–eIF4F interaction, and then scans downstream along the mRNA until the initiation codon, where it stops and results in 48S PIC. Finally, eIF5B promotes the joining of a 60S subunit into an 80S initiation complex and starts the translation. Beyond translation initiation, eIF3 has also been implicated to function at termination stage and is required for ribosome dissociation and recycling (Pisarev et al. 2007; Beznoskova et al. 2013).

Mammalian eIF3 is composed of 13 subunits, eIF3a through m. Based on a series of biochemical and cryo-EM reconstruction assays (Pisarev et al. 2008; Zhou et al. 2008; Elantak et al. 2010; Sun et al. 2011; Querol-Audi et al. 2013; des Georges et al. 2015), the structural assembly of human eIF3 and its interaction with the 40S ribosomal subunit have been elucidated clearly. Six PCI domain-containing subunits (eIF3a, c, e, k, l, and m) and two MPN domain-containing subunits, eIF3f and h, are arranged into a stable octamer; eIF3b, i, and g form a separate module, which adheres to the octamer through interacting with eIF3a; eIF3d attaches to the octamer through binding to eIF3e (Zhou et al. 2008; Karaskova et al. 2012; Querol-Audi et al. 2013; Aylett et al. 2015); while eFI3j is just loosely attached to the octamer by potentially interacting with eIF3a and b (Elantak et al. 2010). The PCI/MPN octamer resides on the solvent side of the 40S ribosomal subunit in a five-lobed shape with eIF3a and eIF3c establishing two contact points; the eIF3b–i–g module resides at the mRNA entrance with eIF3b interacting directly with the 40S subunit; eIF3d is located near the mRNA exit (Pisarev et al. 2008; des Georges et al. 2015). eIF3c, e, and d associate into a module and are involved in the eIF4G-binding and the subsequent mRNA recruitment to the ribosome (Villa et al. 2013).

The functions of individual eIF3 subunits have been underscored. Although not fully characterized, many of them appear to have additional functions beyond the scope of their general scaffolding roles in eIF3 and PIC assembly by showing essentiality for normal growth, development, and differentiation (Dong et al. 2004; Liu et al. 2007; Dong et al. 2009; Choudhuri et al. 2013) or over-expression in some disease conditions (Zhang et al. 2007). The underlying mechanisms were proposed to involve the specific RNA-binding activity and the selective translation control shown by some eIF3 subunits, particularly those not essential for protein synthesis and eIF3 activity, such as eIF3d, g, h, i, k, and l, etc. (Masutani et al. 2007; Choudhuri et al. 2013; Yin et al. 2013). RNA-binding assay and target mRNA determination are helpful to elucidate the function of eIF3 subunits. Accordingly, a recent genome-wide UV crosslinking assay showed that four human eIF3 subunits, eIF3a, b, d, and g, could bind specifically to some cell growth control-related mRNAs at the 5′-untranslated regions (5′-UTRs) and thus potentially endow eIF3 with positive or negative translation control on these genes' expression (Lee et al. 2015). eIF3a has been suggested to regulate translation of a subset of messenger RNAs important for tumorigenesis, metastasis, cell cycle progression, drug response, and DNA repair (Dong et al. 2009).

The composition of trypanosomatid eIF3 was investigated, whereas the structure and function have not been characterized yet. Twelve eIF3 subunits, eIF3a through l, were predicted in T. brucei eIF3 and L. major eIF3 (termed as TbIF3 and LeishIF3, respectively) by deep informatics analysis, and further confirmed by affinity purification and mass spectrometry (MS) assay of the LeishIF3 complex (Rezende et al. 2014; Meleppattu et al. 2015). The gene encoding eIF3m was proposed to be absent in trypanosomatids. Although evolutionarily conserved in complex composition and in some characteristic motifs/domains within various subunits, such as PCI and MPN domains, each LeishIF3 or TbIF3 subunit displays a very low level of sequence identity when compared with their homologs from human and some other lower eukaryotes (Rezende et al. 2014). Among all the subunits, TbIF3f shows the lowest sequence identity at 9% in comparison with human eIF3f, while LeishIF3f shows 29% (Rezende et al. 2014). Meanwhile, it is worth noting that LeishIF3a and TbIF3a proteins lack a large fragment corresponding to ∼620-amino acid length of the C-terminal region of human eIF3a, which was supposed to interact with eIF4B (Methot et al. 1996) and 18S rRNA (Valasek et al. 2003) directly. These variations imply that eIF3 and the related translation regulation should have trypanosome-specific features, which sets a basis for finding effective targets against trypanosomatids.

Most translations occur in a cap-dependent manner in eukaryotes, while some viral mRNAs and a small number of mammalian cellular mRNAs use an internal ribosomal site (IRES) to initiate translation in a cap-independent manner. Based on the structure and the need for eIFs, IRESs are usually divided into three groups, with the IRESs of cricket paralysis virus (CrPV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) as the representatives of Group I, Group II, and Group III, respectively (Kieft 2008). The CrPV IRES-dependent translation is very simple and the 40S ribosomal subunit is enough to sustain it. In contrast, the translations mediated by HCV or EMCV IRES are complicated. They require not only the 40S subunit but also eIF2 and eIF3. Previous study has shown that human eIF3a and eIF3c use their highly conserved RNA-binding motif to bind to the HCV IRES and thereby promote HCV translation (Sun et al. 2013). Moreover, two more initiation factors, eIF1 and eIF5, are essential for EMCV IRES-initiated translation. It is not clear yet whether IRES could mediate translation initiation in trypanosomes or not; however, any exploration on it will provide more or less clues for understanding the translation apparatus in these ancient organisms.

In the present study, we experimentally identified the composition of the tagged-TbIF3a and -TbIF3f complexes and estimated the roles of TbIF3a and TbIF3f in cell growth, total translation, IRES-mediated translation, and eIF3 structure assembly. Meanwhile, the subunits possessing RNA-binding activity were also examined using a genome-wide UV crosslinking assay.

RESULTS

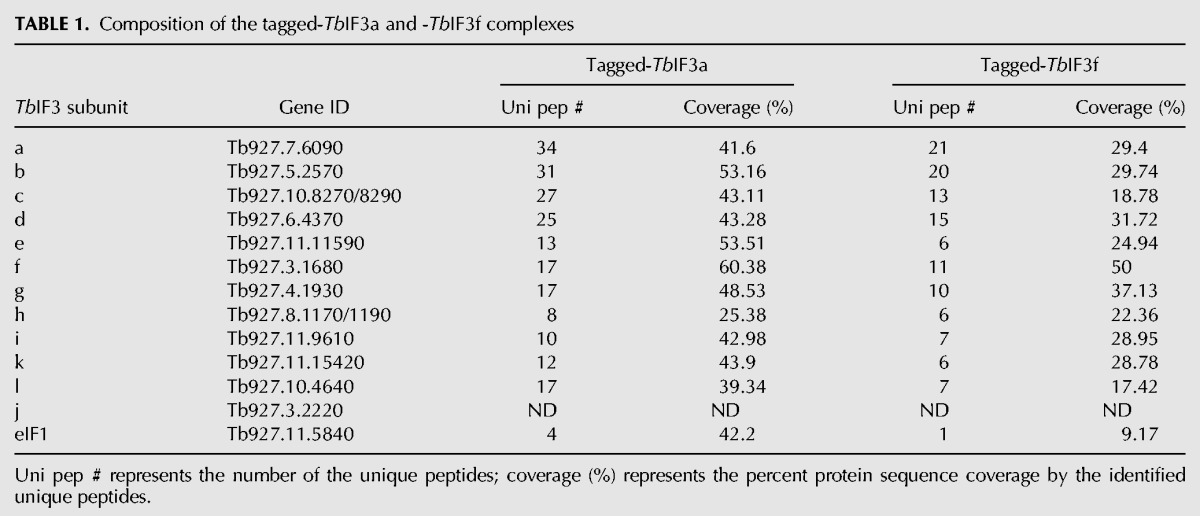

Composition of the tagged-TbIF3a or -TbIF3f complexes

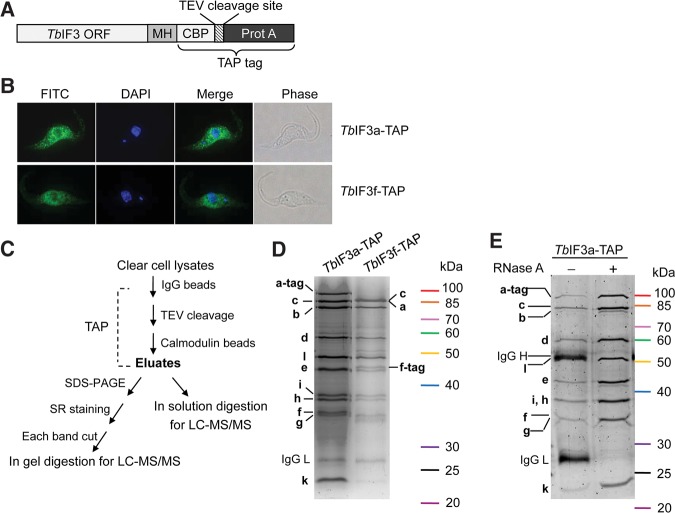

The composition of T. brucei eIF3 was identified through affinity purification and MS determination of the tagged TbIF3 subunits (Fig. 1). A MH-TAP tag was fused to the ORF of the putative TbIF3a or TbIF3f at the C terminus (Fig. 1A). After transfection into PF 29–13 cells and selection, the tagged TbIF3 subunit expressed constitutively from the β-tubulin locus driven by an endogenous promoter. IFA assay showed that the tagged TbIF3a and TbIF3f proteins were mainly localized in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1B), consistent with their potential function in translation. The proteins associated with the tagged TbIF3a or TbIF3f were purified and detected according to the procedures shown in Figure 1C. SDS-PFGE and SYPRO Ruby staining showed that these two protein samples shared a very similar band pattern (Fig. 1D). MS detection of each band revealed that these bands corresponded to the putative TbIF3a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, k, and l proteins (Fig. 1D). MS analysis of the purified protein samples with in-solution digestion showed that the unique peptides number and the percent protein coverage of the 11 TbIF3 subunits were comparable and much greater than those of other copurified proteins, whether associated specifically or contaminated (Table 1, Supplemental Tables S1, S2). The putative TbIF3j was not detected, nor was any potential eIF3m-like counterparts. The putative TbIF1 was the only initiation factor detected in the purified TbIF3a- or TbIF3f-TAP complexes (Table 1), suggesting a strong interaction of TbIF1 with TbIF3. Further RNase A treatment did not alter the band pattern of the purified TbIF3a-tag complex and the relative abundance of each subunit (Fig. 1E), confirming that the assembly of TbIF3 is RNA-independent. Altogether, these results experimentally verified the composition of TbIF3, with each identified subunit exactly matching the bioinformatics prediction. Meanwhile, our results suggest that the identified 11 TbIF3 subunits associate tightly into a stable complex.

FIGURE 1.

Subunit determination of the TbIF3-TAP complex and the TbIF3f-TAP complex. (A) Schematic drawing of a TbIF3 subunit gene in frame fusion with a MH-TAP tag at the C terminus. The MH-TAP is composed of c-myc, 6×His tag, calmodulin binding peptide, TEV protease cleavage site, and protein A as described previously (Guo et al. 2012). (B) Immunofluorescence assay of the subcellular localization of the tagged TbIF3a and TbIF3f proteins. (C) Overview of the procedures purifying the tagged TbIF3 subunit complexes and determining the protein composition. TAP, tandem affinity purification; SR staining, SYPRO Ruby staining. (D) SDS-PAGE followed by SR staining of the purified TbIF3a-TAP (left lane) and TbIF3f-TAP (right lane) complexes. Individual band was excised and used for MS determination. The names of the proteins corresponding to each band are labeled. (E) SDS-PAGE followed by silver staining of the proteins associated with the tagged TbIF3a before (−) and after RNase A (+) treatment through TAP purification.

TABLE 1.

Composition of the tagged-TbIF3a and -TbIF3f complexes

TbIF3a and TbIF3f are essential for viability

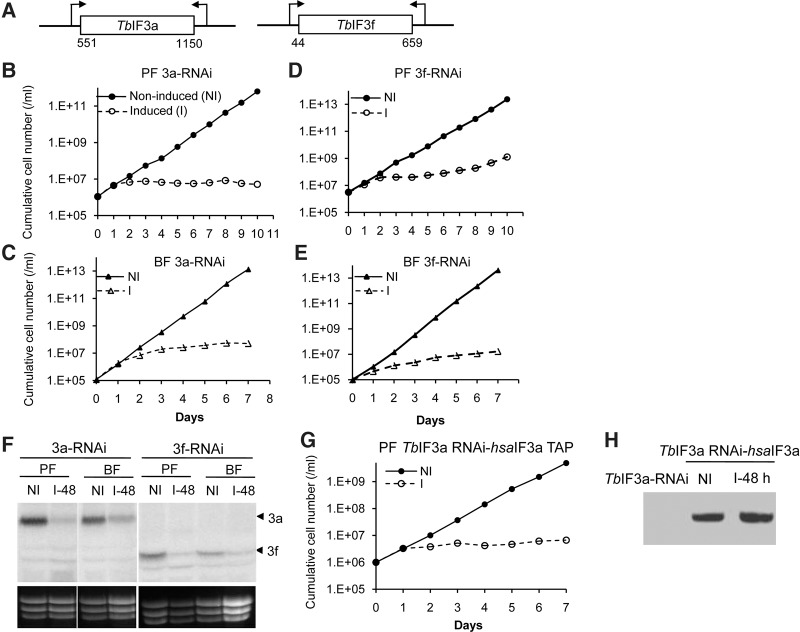

The essentiality of TbIF3a and TbIF3f for growth was assessed in PF and BF stages of T. brucei (Fig. 2). Four tet-inducible RNAi cell lines, including PF TbIF3a-RNAi, BF TbIF3a-RNAi, PF TbIF3f-RNAi, and BF TbIF3f-RNAi, were generated. The presence of tet induces the synthesis of dsRNAs targeting TbIF3a or TbIF3f (Fig. 2A). The growth of all the RNAi-induced cells, whether in PF or BF life stages, was severely inhibited; in contrast, the RNAi noninduced cells grew normally (Fig. 2B–E). Northern blot analysis revealed that the mRNA levels of TbIF3a or TbIF3f reduced significantly after RNAi induction for 48 h (Fig. 2F). Overall, significant growth inhibition of PFs and BFs upon repression of either TbIF3a or TbIF3f expression indicates that these two TbIF3 subunits are essential for the viability of both life stages of T. brucei.

FIGURE 2.

TbIF3a and TbIF3f are necessary for the growth of PF and BF T. brucei. (A) Schematic representation of the dsRNA-expressing vectors. The number represents the location of the dsRNA sequence within the coding region of TbIF3a or TbIF3f. Growth curves of PF TbIF3a-RNAi (B), BF TbIF3a-RNAi (C), PF TbIF3f-RNAi (D), and BF TbIF3f-RNAi (E) cell lines in which RNAi knockdown TbIF3a or TbIF3f was induced (I) or noninduced (NI). (F) Northern blot analysis of the RNAi knockdown efficiency with the probe against the 5′-proximal coding region of TbIF3a or TbIF3f. NI and I-48 represent RNAi noninduced and induced for 48 h, respectively. EtBr-stained rRNA was used to show the loading. The targeted mRNAs are indicated on the right. (G) Growth of PF TbIF3a RNAi-hsaIF3a TAP cell line with RNAi induced (NI) or noninduced (I). (H) Western analysis of hsaIF3a-TAP in the cell lysate from PF TbIF3a-RNAi cells or from PF TbIF3a RNAi-hsaIF3a TAP cells in which RNAi was noninduced (NI) or induced for 48 h (I-48 h) with rPAP reagent. Cumulative cell number represents the cell density multiplied by total dilution.

The effect of human eIF3a (hsaIF3a) expression on the growth deficiency upon TbIF3a depletion was estimated. hsaIF3a-TAP was introduced into the β-tubulin locus of PF TbIF3a-RNAi, resulting in the cell line PF TbIF3a RNAi-hsaIF3a TAP. Its growth was normal in the absence of tet but inhibited severely in the presence of tet (Fig. 2G), very similar to that of PF TbIF3a-RNAi cells (Fig. 2B). Further Western analysis indicated that the expression of hsaIF3a was well and not affected by the expression of dsRNA against TbIF3a (Fig. 2H). Therefore, the growth deficiency that resulted from TbIF3a depletion could not be rescued by its human homolog.

RNAi knockdown of TbIF3a or TbIF3f inhibits translation initiation

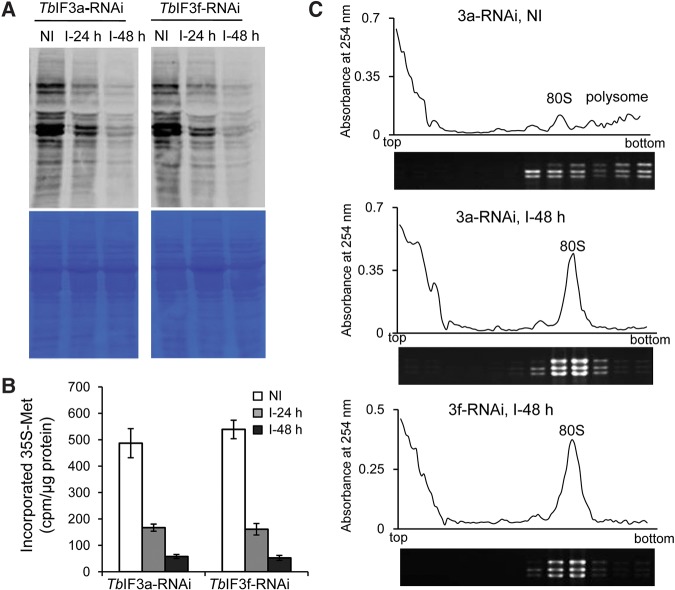

The functions of the putative TbIF3a and TbIF3f in translation initiation were investigated by performing 35S-Met incorporation assay and polysome profile analysis (Fig. 3). PF TbIF3a-RNAi or TbIF3f-RNAi cells in which RNAi was not induced or induced for 24 or 48 h were pulse-labeled with 35S-Met for 60 min. The cell extracts from equal numbers of cells were examined by SDS-PAGE. Coomassie blue staining of the gel showed that the total protein level changed little upon depletion of either TbIF3a or TbIF3f (Fig. 3A, lower panel), while an autoradiograph of the same gel revealed that the newly synthesized proteins reduced significantly at 24 h after RNAi induction and much more at 48 h (Fig. 3A, upper panel). Further scintillation counting the TCA precipitates showed that the radioactivity of the cells with RNAi induced for 24 or 48 h reduced to less than 40% or 8%, respectively, compared to the value of the cells with RNAi noninduced (Fig. 3B). The big reduction in 35S-Met incorporation therefore indicates that depletion of either TbIF3a or TbIF3f blocks total protein synthesis.

FIGURE 3.

Depletion of either TbIF3a or TbIF3f results in translation inhibition. 35S-Met was added to the PF TbIF3a-RNAi or TbIF3f-RNAi cells in which RNAi was not induced or induced for 24 or 48 h. After incubation for 60 min, the cells with equal numbers were collected and lysed. (A) The clear cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie blue staining (lower panel) and autoradiograph (upper panel). (B) The radioactivity of the newly synthesized proteins was measured by scintillation counting of the TCA-precipitated proteins. The assays were repeated three times and the results were shown as mean ± SD. (C) Polysome profile analysis of PF TbIF3a-RNAi and TbIF3f-RNAi cells in which RNAi was not induced (NI) or induced for 48 h (I-48 h) through sucrose-gradient centrifugation. Ninety-six fractions were taken and measured absorbance at 254 nm. Every eight fractions were combined, and RNAs were extracted and separated on agarose gel followed by EtBr staining to visualize rRNAs. The positions of 80S ribosome and polysomes are indicated.

The inhibiting effect of TbIF3 subunit depletion on protein synthesis was also readily seen when polysome profiles were determined via sucrose-gradient centrifugation. Following RNAi knockdown of either TbIF3a or TbIF3f for 48 h, polysomes were severely dropped and 80S ribosomes increased dramatically according to the change of UV absorbance at 254 nm and the rRNA distribution in the gradient fractions (Fig. 3C). Given that a reduction in the polysome-to-monosome ratio is a hallmark of impaired translation initiation rates, these results together indicate that the putative TbIF3a and TbIF3f are required for translation initiation and TbIF3 activity.

TbIF3a or TbIF3f knockdown exhibits a different effect on the structure assembly of TbIF3

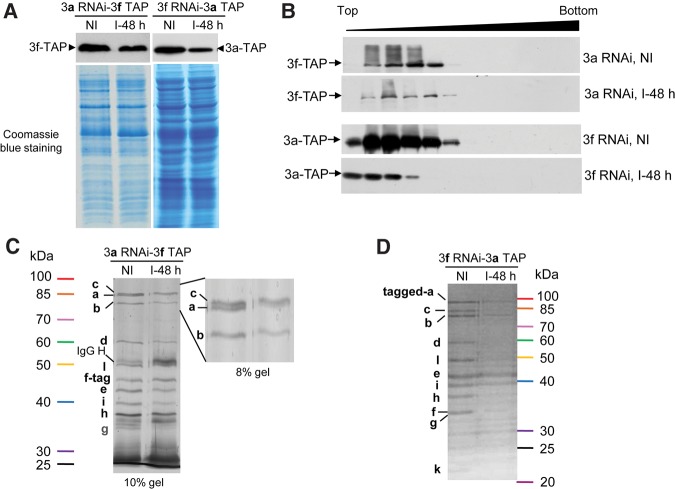

The role of TbeIF3a in the formation of TbIF3 was estimated by analyzing the composition of the tagged-TbIF3f complex upon depletion of TbIF3a by RNAi, and vice versa (Fig. 4). The PF RNAi cell line TbIF3a-RNAi or TbIF3f-RNAi was modified to result in the cell line 3a RNAi-3f TAP or 3f RNAi-3a TAP, which expresses TAP-tagged TbIF3f or TbIF3a constitutively from the β-tubulin locus, respectively. Equal numbers of each cell line with or without RNAi induced for 48 h were harvested and lysed individually. Western analysis of the cell lysates showed that the tagged-TbIF3f or -TbIF3a reduced moderately upon TbIF3a or TbIF3f depletion, respectively (Fig. 4A), suggesting an essentiality of these two subunits for TbIF3 stability. Sucrose-gradient centrifugation followed by Western analysis showed that TbIF3a depletion did not change the distribution of TbIF3f-TAP in the gradient fractions (Fig. 4B, upper panels); while TbIF3a-TAP up-shifted upon TbIF3f depletion (Fig. 4B, lower panels), suggesting that TbIF3f, but not TbIF3a, should be critical for the integrity of TbIF3. This speculation was further supported by the composition change of TbIF3 upon repression of the subunit expression. As shown in Figure 4C, almost all other subunits copurified with the tagged-TbIF3f protein upon depletion of TbIF3a, suggesting that TbIF3a may be located at the periphery of the TbIF3 complex or not critical for the assembly of TbIF3. In contrast, only subunits TbIF3b, e, and i were clearly observed to copurify with the tagged-TbIF3a protein upon depletion of TbIF3f, while other subunits were almost indiscernible (Fig. 4D). This result suggested a stable subcomplex composed of subunits a, b, i, and e, which is somewhat different from other eukaryotic eIF3 structure models in which eIF3a, b, i, and g form a stable subcomplex (Dong et al. 2013; Wagner et al. 2014), implying a distinctive TbIF3 in structural assembly. More importantly, this result revealed a critical scaffolding role of TbIF3f. Therefore, TbIF3a and TbIF3f function differently in TbIF3 structure assembly, and their respective roles appear to be somewhat distinct from their mammalian counterparts.

FIGURE 4.

Effects of TbIF3a or TbIF3f repression on tagged TbIF3f or TbIF3a complexes, respectively. (A) Western analysis of the whole-cell lysate of PF 3a RNAi-3f TAP or 3f RNAi-3a TAP in which RNAi was not induced or induced for 48 h with rPAP reagent (upper panel). Coomassie blue staining of the membrane showed proteins load (lower panel). (B) Sedimentation profiles of the tagged-TbIF3a or -TbIF3f in the sucrose-gradient fractions by Western blot. The fractions from top to bottom are indicated. SYPRO Ruby stained gels of the TbIF3f-tag complexes (C) or the TbIF3a-tag complexes (D) purified from PF 3a RNAi-3f TAP or PF 3f RNAi-3a TAP cells via TAP purification, respectively, in which RNAi was not induced (NI) or induced for 48 h (I-48 h). Portions of SYPRO Ruby stained 8% gel are enlarged (C, right panel) to show the depletion of TbIF3a after 48 h of tet addition.

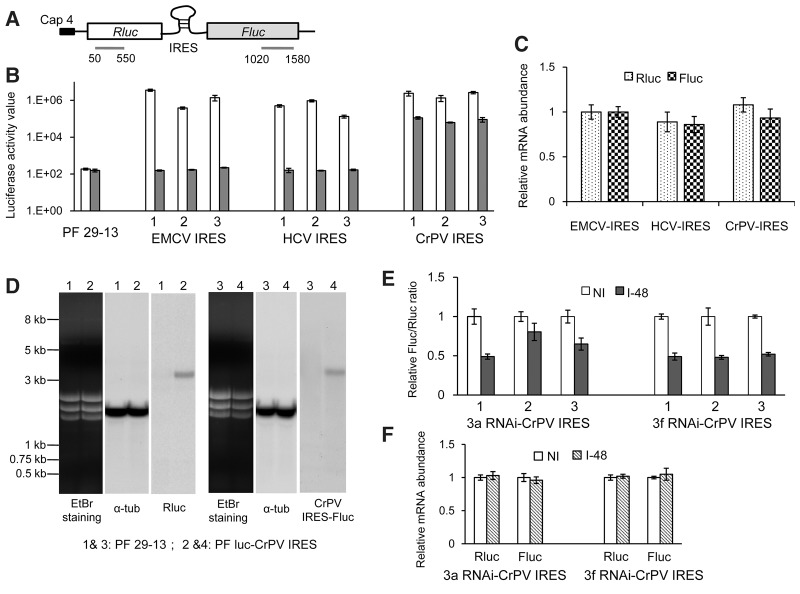

CrPV IRES could mediate translation in T. brucei in the presence of TbIF3a and TbIF3f

To examine whether or not IRES could initiate translation in T. brucei, the expressions of different IRES-containing dual-reporters were detected in PF 29-13 cells. These dual-reporter vectors were pHD1344-based, with an upstream Rluc ORF and a downstream Fluc ORF linked by one out of EMCV IRES, HCV IRES, and CrPV IRES (Fig. 5A). Three cell lines, PF luc-EMCV IRES, PF luc-HCV IRES, and PF luc-CrPV IRES, were generated in which Rluc was expressed in a cap-dependent manner while Fluc in an IRES-dependent manner. Three clones from each cell line were examined for the reporters' expression at mRNA and protein levels. As shown in Figure 5B, the Rluc activity values were similar among all these IRES-harboring clones and much higher than the background signal of the PF 29-13 cell; while the Fluc activity values in any of these EMCV IRES- or HCV IRES-containing clones were almost equal to the background signal. However, the Fluc activity values from CrPV IRES-containing cells were much greater. Total RNAs were isolated from one random clone of each cell line and used for reporters mRNA measurement, with 18S rRNA used as an internal control. The results showed that the relative mRNA levels of Rluc or Fluc were similar in all these tested clones (Fig. 5C), suggesting that the presence of IRES has no effect on transcription and mRNA stability. Northern blot analysis of the cell PF luc-CrPV IRES showed that the only hybridizing band of Rluc mRNAs and that of Fluc mRNAs were located at the same position with a size ranging from 3 to 4 kb (Fig. 5D), corresponding to the nucleotide length of Rluc-CrPV IRES-Fluc from the reporter plasmid. This result indicated that the mRNAs of Rluc and downstream Fluc are present as dicistronic Rluc-CrPV IRES-Fluc transcripts in the cell PF luc-CrPV IRES, and CrPV IRES should be responsible for the Fluc translation. Therefore, CrPV-IRES, but neither HCV-IRES nor EMCV-IRES, could initiate the translation in T. brucei, which suggests that eIFs involved in IRES-mediated translation between trypanosomes and mammals may be functionally different.

FIGURE 5.

CrPV IRES could mediate translation in the presence of TbIF3a and TbIF3f. (A) Schematic representation of the dual-reporter vector with different IRES between an upstream Rluc ORF and a downstream Fluc ORF. Blue line segments show the Northern blot probe specific to Rluc or Fluc. The numbers represent the location of the probe sequence within the coding region of the reporters. (B) Luciferase activity assay of PF EMCV IRES-luc, HCV IRES-luc, and CrPV IRES-luc cells. Three clones from each cell line are marked as 1, 2, and 3 randomly. The parent cell line PF29-13 was used as control. (C) Real-time RT-PCR analysis of the total RNAs from one random clone of each cell line in panel A for Rluc and Fluc mRNA's measurement. The relative reporter mRNA levels of the cell PF EMCV IRES-luc were set as one. (D) Northern blot analysis of the cell PF luc-CrPV IRES and the control cell PF 29-13, with the probe specific to Rluc (lanes 1 and 2) or Fluc (lanes 3 and 4), then stripped and rehybridized with the probe specific to α-tubulin. EtBr staining of the rRNAs is shown. (E) Luciferase activity assay of the cell lysates from TbIF3a RNAi-CrPV IRES and TbIF3f RNAi-CrPV IRES cells in which RNAi was not induced (NI) or induced for 48 h (I-48). Three clones from each cell line, marked as 1, 2, and 3, were tested and the relative Rluc/Fluc ratio was calculated, with that in RNAi noninduced cells set as one. (F) Real-time RT-QPCR analysis of the total RNA from one random clone of each cell line in panel D. The relative Rluc and Fluc mRNA levels from RNAi induced cells were shown relative to those of the same cell lines in which RNAi was not induced. β-Tubulin was used as the internal control for all of these real-time RT-PCR analyses. At least three independent experiments were carried out, and the results are shown as mean ± SD.

The effect of TbIF3a and TbIF3f repression on CrPV IRES-mediated translation was estimated. The CrPV IRES-containing dual-reporter vector was transfected and integrated into the β-tubulin locus of PF TbIF3a-RNAi and Tb3f-RNAi cells and resulted in 3a RNAi-CrPV IRES and 3f RNAi-CrPV IRES cell lines, respectively. Similarly, three clones from each cell line were examined for the reporters' expression by luciferase activity assay. As shown in Figure 5E, down-regulation of either TbIF3a or TbIF3f by RNAi did not alter the Rluc protein level but reduced the Fluc proteins to 50% compared to the RNAi noninduced cells. Real-time PCR analysis of the RNA samples from a random clone of either cell line showed that both Fluc and Rluc mRNA abundances were not affected upon TbIF3a or TbIF3f knockdown (Fig. 5F). Therefore, these results indicate that depletion of either TbIF3a or TbIF3f could result in repression of CrPV IRES-mediated translation.

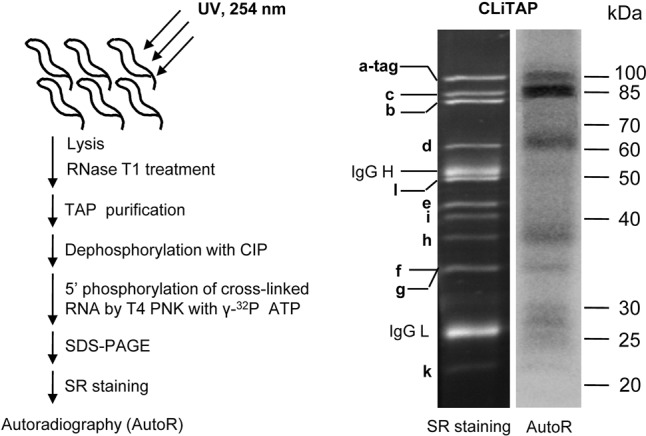

TbIF3 subunits TbIF3a, c, d, and h exhibit RNA-binding activity

Whether and which TbIF3 subunit(s) could bind to RNA directly was detected by using the CLiTAP approach, as described previously (Yue et al. 2014). As shown in Figure 6A, the TbIF3a-TAP complex was purified from the PF TbIF3a-TAP cells after UV crosslinking. After RNase T1 treatment and TAP purification, the bound RNAs were labeled with [γ-32P]ATP. The purified complexes were resolved by SDS-PAGE. SYPRO Ruby staining was compared to the autoradiograph of the same gel, and the result showed that subunits TbIF3a, c, d, and h crosslinked directly to RNA with TbIF3c exhibiting the strongest signal; the overlapped TbIF3f and g proteins band corresponded to a very weak radioactive signal, suggesting a potential RNA-binding activity of f and/or g; while TbIF3e, i, k, and l did not show any visible radioactive signals, suggesting no direct RNA-binding activity. In addition, the RNA-binding activity of TbIF3b remained elusive because of the potential RNA signal overlapping between b and c (Fig. 6B). Overall, this genome-wide UV crosslinking assay indicates that at least four TbIF3 subunits, including TbIF3a, c, d, and h, have direct RNA-binding activity.

FIGURE 6.

Genome-wide UV crosslinking assay of the RNA-binding activity of TbIF3. (A) Strategy of CLiTAP. CLiTAP represents UV crosslinking and TAP purification. (B) RNA-binding activity assay of the purified TbIF3a-TAP complex through CLiTAP. The purified complexes were resolved on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel, followed by SYPRO Ruby staining (left panel) and autoradiograph (right panel). The proteins corresponding to each band are indicated.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we experimentally confirmed that the eIF3 complex of T. brucei is composed of 11 subunits, consistent with the previous bioinformatics prediction (Rezende et al. 2014), except that TbIF3j was not detected. Since the TbIF3j counterpart, LeishIF3j, was found in the LeishIF3e pull-down complex with a relatively low protein abundance factor, the missing detection of TbIF3j adds to the evidence that eIF3j may be loosely associated with the eIF3 complex in trypanosomes as well. Importantly, we demonstrated here that both TbIF3a and TbIF3f are structurally and functionally essential for TbIF3, although TbIF3f was not identified by deep informatics analysis due to an extremely low sequence identity to its homologs (Rezende et al. 2014). RNAi knockdown of either TbIF3a or TbIF3f could significantly inhibit growth of PFs and BFs (Fig. 2B–E) and shut down the translation initiation (Fig. 3). At translational termination stage, eIF3 is a principal factor that can promote both splitting of post-termination ribosomes into 40S and 60S subunits and initiation of a new round of translation (Kolupaeva et al. 2005; Pisarev et al. 2007; Beznoskova et al. 2013). Polysome profile analysis showed that depletion of either TbIF3a or TbIF3f resulted in significant accumulation of 80S ribosomes and dramatic reduction of polysomes, while no absorbance increase was observed in the potential 40S and 60S ribosome subunits area (Fig. 3C). Therefore, TbIF3a and TbIF3f subunits may be necessary for ribosome dissociation in T. brucei, and TbIF3 should play a critical role in ribosome recycling.

Structural characterizations of the tagged TbIF3 complex by reciprocally expressing TbIF3a-TAP and TbIF3f-TAP in TbIF3f RNAi and TbIF3a RNAi cells, respectively, reveal that these two subunits play different roles in the stability or integrity of TbIF3 structure. TbIF3a knockdown caused a modest reduction in the tagged-TbIF3f protein level but had little effect on the composition of the residual TbIF3f-TAP complex (Fig. 4A–C), suggesting that TbIF3a is required for the stability of TbIF3 but not indispensable for the integrity and the structure assembly. In stark contrast, mammalian eIF3a plays a critical scaffolding role in the octamer formation and is necessary for the entire eIF3 complex assembly (Masutani et al. 2007). Human eIF3a knockdown disrupted the entire eIF3 complex and severely reduced the octamer subunits (Wagner et al. 2014). The functional difference between TbIF3a and its mammalian homolog can be somewhat reflected by their sequence variations. Although the characteristic PCI domain, Spectrin repeats, and the putative RNA-binding motif are conserved (Wagner et al. 2014), the overall sequence identity is as low as 22%. Moreover, TbIF3a is just a little more than half the length of human eIF3a, while the function of this missing sequence has not been well characterized yet. We thus speculate that human eIF3a and TbIF3a are not functionally replaceable. As expected, expression of human eIF3a in PF TbIF3a-RNAi cells could not restore the growth defect of T. brucei upon TbIF3a repression by RNAi (Fig. 2G).

Distinct from the moderate impact of TbIF3a knockdown, TbIF3f knockdown caused the upshift of TbIF3a in the sucrose-gradient fractions and the disruption of the TbIF3a-TAP complex, and only TbIF3b, i, and e were clearly observed to copurify with TbIF3a (Fig. 4B,D). These results indicate that TbIF3f is essential for TbIF3 stability and integrity and plays a principal role in TbIF3 structure assembly. In contrast, mammalian eIF3f interacts with eIF3h directly, and seems not indispensable for other eIF3 subunits assembly, based on previous reports (Zhou et al. 2008; Pukala et al. 2009). In addition, TbIF3f knockdown resulted in polysome reduction and translation initiation inhibition (Fig. 3), while human eIF3f depletion promoted the translation initiation (Wen et al. 2012). In all, these observations indicate the functional divergence of TbIF3a and TbIF3f from their higher eukaryotic orthologs, implying a trypanosome-specific structural assembly of TbIF3.

The absence of the eIF3m-encoding gene in T. brucei also highlights the specific structural features of TbIF3. As a PCI subunit, mammalian eIF3m forms a compact trigonal subcomplex with the MPN dimer eIF3f–eIF3h and mediates the association with the octamer mainly through eIF3f–eIF3m interaction (Zhou et al. 2005, 2008). eIF3m deficiency significantly down-regulated the subunits eIF3f, h, and c, and impaired the integrity of eIF3 (Zeng et al. 2013). Since eIF3m is essential for eIF3 structure and function in mammals, the absence of eIF3m (Rezende et al. 2014; Meleppattu et al. 2015) and the low sequence similarity of other eIF3 subunits suggest that the eIF3 of trypanosomatids should have unique structure and diverged subunits function. We speculate that eIF3m may have evolved for some specific functions in translation control under some particular conditions. However, more experiments are required to decipher the roles of the individual subunit in TbIF3 structure and activity.

A previous study has shown that eIF3 can interact with eIF1, eIF1A, eIF2, and eIF5 directly to form a multifactor complex (MFC), which promotes the association of 40S ribosomal subunits and eIF2-GTP-Met-tRNAi into 43S PIC (Sokabe et al. 2012). The existence of this MFC has also been suggested in L. major based on the observation that LeishIF1, Leish1A, LeishIF2, and LeishIF5 could copurify with LeishIF3 (Meleppattu et al. 2015). Among them, the interaction between LeishIF1 and LeishIF3 is the strongest, with the relative protein abundance factor of LeishIF1 higher than other initiation factors. Consistently, we discerned a coprecipitation of the putative TbIF1 with the tagged-TbIF3a complex and the tagged-TbIF3f complex, but no other MFC components were identified, nor other eIFs interacting with eIF3 directly, such as eIF4G (Villa et al. 2013). The association of TbIF1 with TbIF3, however, adds to evidence that MFC is potentially present in trypanosomatids. The under-detection of other eIFs in our purification may be due to the transient or weak interaction and/or stringent two-step affinity purification. This speculation was supported by the missing TbIF3j in the purified TbIF3 complex, while its L. major homolog was detected in the purified LeishIF3 complex (Meleppattu et al. 2015).

The dual-reporter system containing different types of IRES works well in mammalian cells (Zhu et al. 2012 and references therein). However, luciferase activity assay and RNA analysis showed that only CrPV IRES, but neither EMCV IRES nor HCV IRES, could initiate reporter translation in T. brucei (Fig. 5B–D). These results suggest that the eIFs involved in EMCV IRES- or HCV IRES-mediated translation, including eIF1, eIF2, and eIF3 (Kieft 2008), should be different from their mammalian counterparts in composition, subunits arrangement or function. Given that the presence of a 40S ribosomal subunit is enough to initiate CrPV-IRES-mediated translation, we propose that the mechanism of TbIF3a or TbIF3f knockdown inhibiting the CrPV-IRES-mediated translation can be attributed to the accumulation of 80S ribosomes and the potential decrease of 40S subunits. Although the T. brucei ribosome has an unusually large and unique arrangement of expansion segments revealed by a high-resolution cryo-EM (Hashem et al. 2013), this unusual structure did not interfere with the translation of CrPV IRES-mediated translation.

Direct RNA-binding activity is indispensable for eFI3 functioning in translation initiation and translation control. The genome-wide UV crosslinking experiment has shown that several TbIF3 subunits have direct RNA-binding activities with various efficiencies (Fig. 6B). The most notable is TbIF3c, which exhibits a much stronger RNA-binding signal than other RNA-binding subunits. In contrast, its human homolog did not show any RNA-binding activity in a genome-wide UV crosslinking experiment (Lee et al. 2015). However, a highly conserved helix–loop–helix (HLH) RNA-binding motif (RRM) was predicted in eIF3c, which has been verified to contribute to the binding to the IIIabc domain within HCV IRES and direct HCV IRES-dependent translation together with TbIF3a (Sun et al. 2013). Sequence alignment between TbIF3c and human eIF3c showed that their overall sequence identity was as low as 20.4% and the HLH domain was not predicted in TbIF3c by Phyre2 (Supplemental Fig. S1), a protein structure prediction software (Kelley and Sternberg 2009). These results suggest that TbIF3c may use different RNA-binding motif(s) for cellular mRNA binding. Further determination and characterization of the RNAs bound to TbIF3a, c, d, and h will be helpful to uncover the mechanisms of TbIF3 underlying translation initiation and translation control in the species of Trypanosomatids.

In conclusion, our data experimentally highlight the trypanosome-specific structural assembly of TbIF3 and subunit function, although the composition is conserved evolutionarily from protozoan to mammals. These findings provide a basis for future investigation of translation in trypanosomes, and suggest that TbIF3a and TbIF3f can be potential targets for developing new drugs against trypanosomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction

To create the vectors expressing C-terminally TAP-tagged proteins, T. brucei 427 genomic DNA was used as a template to amplify the full-length open reading frames (ORFs) of TbIF3a and TbIF3f by using the primers 5′-CACGTCGACATGTTGCAAGCGGAAGTA-3′ plus 5′-CACGGATCCCTTCCCTTGTAGGCGCTC-3′ and the primers 5′-CACCTCGAGATGCGAAATTCCGCTGGT-3′ plus 5′-CACGGATCCACGGGTATTATTTCCTCT-3′, respectively. After digestion with SalI or XhoI, and BamHI, the PCR products were cloned into the similarly digested pHD1344-MHTAP (Guo et al. 2012), which contains a MH-TAP-coding region following the cloning sites (Fig. 1A), to generate the constructs pHD1344-3a-TAP and pHD1344-3f-TAP. The plasmids expressing tetracycline (tet)-inducible RNAi for TbIF3a or TbIF3f were constructed as follows: A 600- or 616-bp fragment corresponding to the middle region of TbIF3a ORF or the 5′-terminal region of TbIF3f ORF (Fig. 2A) was amplified from the genomic DNA by using the primers 5′-CACAAGCTTTTGAACTCTGCAGGACG-3′ and 5′-CACCTCGAGTACGCTGCACTAAGAAG-3′ or the primers 5′-CACAAGCTTGCCAGATCACAGTAACG-3′ and 5′-CACCTCGAGATATCCTGCATCATTCC-3′, respectively. The PCR products were digested with XhoI and HindIII and inserted into similarly digested pZJM (Wang et al. 2000) to create pZJM-3a and pZJM-3f. Human genomic DNA was extracted from 293T cells and eIF3a was amplified by using RT-PCR with the primers 5′-CACGTCGACATGCCGGCCTATTTTCAGAG-3′ and 5′-CACAGATCTACGTCGTACTGTGGTCCATC-3′. The PCR products were digested with SalI and BglII and then cloned into similarly digested pHD1344-MHTAP to create pHD1344-hsaIF3a TAP. To create the IRES-containing dual-reporter plasmids capable of integration into T. brucei genome, a pair of primers 5′-CACGTCGACATGACTTCGAAAGTTTATG-3′ and 5′-CACGGATCCTTACAATTTGGACTTTCC-3′ were used to amplify the Renilla luciferase (Rluc)-CrPV IRES-firefly luciferase (Fluc), Rluc-HCV IRES-Fluc, and Rluc-EMCV-IRES-Fluc from the plasmids pNL4-3RL-CrPV-FL, pNL4-3RL-HCV-FL, and pNL4-3RL-EMCV-FL (Zhu et al. 2012), respectively. After digestion with SalI and BamHI, these PCR products were inserted into the plasmid pHD1344tub (Carnes et al. 2005) digested with XhoI and BamHI to generate pHD1344-Dual-luc-CrPV IRES, pHD1344-Dual-luc-CrPV IRES, and pHD1344-Dual-luc-CrPV IRES. The restriction sites are underlined. The plasmids pHD1344-MHTAP (Guo et al. 2012) and pHD1344tub (Carnes et al. 2005) target the integration of the inserted genes into β-tubulin locus.

Cell culture and cell line generation

The starting cell lines T. brucei PF 29-13 and BF single-marker (BF-SM) were maintained in SDM-79 medium and HMI-9 medium, respectively, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and selection marker(s) as described previously (Wirtz et al. 1999). The plasmids pHD1344-3a-TAP and pHD1344-3f-TAP were linearized by NotI and individually transfected into PF 29-13. After selection with puromycin (1 µg/mL), the resulting stable cell lines were designated PF TbIF3a-TAP and TbIF3f-TAP. Expression of the tagged genes was determined by Western blot. To generate tet-inducible RNAi cell lines in both life stages of T. brucei, PF 29-13 and BF-SM cell lines were transfected independently with 10 µg of NotI-linearized pZJM-3a or pZJM-3f. The resulted phleomycin-resistant clones were named PF TbIF3a-RNAi, BF TbIF3a-RNAi, PF TbIF3f-RNAi, and BF TbIF3f-RNAi. The PF TbIF3a RNAi-hsaIF3a TAP cell line was generated by transfecting the NotI-linearized pHD1344-hsaIF3a TAP into the PF TbIF3a-RNAi cell line. The PF 3a RNAi-3f TAP and 3f RNAi-3a TAP cell lines were generated by transfecting pHD1344-3f-TAP and pHD1344-3a-TAP into the PF RNAi cell lines TbIF3a-RNAi and TbIF3f-RNAi, respectively. The expression of these tagged genes was confirmed by Western blot. Ten micrograms of NotI-linearized pHD1344-CrPV IRES-luc, pHD1344-HCV IRES-luc, or pHD1344-EMCV IRES-luc were transfected into PF 29-13, and the puromycin-resistant clones were designated PF luc-CrPV IRES, PF luc-HCV IRES, or PF luc-EMCV IRES, respectively. The linearized pHD1344-CrPV IRES-luc was additionally transfected into PF TbIF3a-RNAi and TbIF3a-RNAi cells, the resulting resistant clones were named PF 3a RNAi-CrPV IRES and 3f RNAi-CrPV IRES, respectively.

Cell growth

DsRNA was induced by adding 1 µg of tet/mL. Growth of the RNAi cells was monitored in the absence or in the presence of tet and counted daily with a hemocytometer. The PF cells were maintained between 2 × 106 and 2 × 107 cells/mL while the BF cells were maintained between 1 × 105 and 2 × 106 cells/mL.

Immunofluorescence assay (IFA)

Subcellular localization of the tagged TbIF3a or TbIF3f was determined by IFA as described previously (Lerch et al. 2012). The rabbit polyclonal antibody against c-myc (Sigma-Aldrich) and the FITC-labeled anti-rabbit IgG (Sigma-Aldrich) were used as primary and secondary antibody, respectively, to visualize the tagged proteins. DNA was visualized by treatment with DAPI (Roche). The fluorescence and phase-contrast images of the cells were captured with a fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX63).

Tandem affinity purification (TAP) and mass spectrometry analysis (MS)

A total of 1 × 1010 cells expressing TAP-tagged TbIF3a or TbIF3f were harvested and lysed, and the tagged complexes were purified through TAP purification essentially as described previously (Rigaut et al. 1999; Panigrahi et al. 2003). Briefly, IgG affinity chromatography, TEV protease cleavage, and calmodulin affinity chromatography were carried out in a stepwise order to purify the TAP-tagged complexes from the cell lysate. The purified proteins were resolved on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and stained with SYPRO Ruby (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The protein bands were cut and digested in gel with trypsin. In parallel, the total proteins were digested in solution with trypsin. All the protein samples were subjected to liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis using the service provided by Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI). The T. brucei protein database downloaded from TriTrypDB. All MS/MS samples were analyzed using Mascot 2.3.02 (Matrix Science), and peptides and protein were specified using PeptideProphet and ProteinProphet algorithms.

RNA isolation and Northern blot

Total RNA was isolated from the RNAi cells in which RNAi was not induced or induced for 48 h, or from PF 3a RNAi-CrPV IRES and PF 29-13 cells, using the TRIzol Reagent (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Twenty micrograms of RNA from each sample was resolved on a formaldehyde-containing 1.2% agarose gel and then transferred to a Hybond N+ membrane (GE Amersham Biosciences). The RNA samples from RNAi cells were hybridized with the DIG-labeled probe specific to TbIF3a or TbIF3f. The RNAs from PF 3a RNAi-CrPV IRES and PF 29-13 cells were hybridized with the labeled probe specific to Rluc or Fluc (Fig. 5A), and then stripped and rehybridized with the probe specific to α-tubulin, which was used as a control. Probe labeling and signal detection were conducted with DIG High Primer DNA Labeling and Detection Starter Kit II according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche Diagnostics). The rRNAs were observed through ethidium bromide (EtBr) staining.

Real-time reverse transcriptase PCR (real-time RT-PCR)

Real-time RT PCR was carried out to measure the mRNA levels of Rluc and Fluc. Total RNAs were isolated from the cells expressing different IRES-containing reporters in the absence or presence of tet for 48 h as described above. Five micrograms of RNA were treated with DNase I (Promega) and the integrity was confirmed by visualizing on an agarose gel. The cDNA templates for real-time PCR were reversely transcribed from 2 µg treated RNA by using random hexamers and PrimeScript RT reagents (Takara). Control reactions without reverse transcriptase were performed to eliminate genomic DNA contamination. The cDNA reaction mixtures were diluted 1:5 in water as the template for PCR detection of Rluc and Fluc, and further diluted 1:50 for amplification of the internal control β-Tubulin. The sequences of the primers for Rluc and Fluc are 5′-ATAACTGGTCCGCAGTGGTG-3′ plus 5′-AGGCCGCGTTACCATGTAAA-3′ and 5′-TTGTTTTGGAGCACGGAAAGAC-3′ plus 5′-AAGACCTTTCGGTACTTCGTCC-3′, respectively. The sequences for β-tubulin have been described previously (Carnes et al. 2005). Each PCR reaction contained 2 µL of cDNA, 8 μL of forward and reverse primers (each at 0.75 µM), and 10 µL of SRBR green PCR Supermix (Bio-Rad). The amplification condition was 95°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 sec and 60°C for 30 sec, using Bio-Rad CFX96 thermocycler. Each reaction was carried out in triplicate. Thermal dissociation curves confirmed that the PCR generated a single amplicon. The target mRNA levels were normalized to β-Tubulin.

35S-Met pulse labeling assay

The pulse labeling and incorporation counting assay was carried out according to the previous description with some modifications (Dhalia et al. 2006). Briefly, PF TbIF3a-RNAi and TbIF3f-RNAi cells in which RNAi was not induced as a control, or induced for 24 or 48 h, were pulse-labeled with 100 µCi of 35S-Met/mL for 60 min at 27°C. Labeling was terminated by adding 3 volumes of stop solution (1.2 mg/mL methionine and 0.1 mg/mL cycloheximide [CHX] suspended in PBS). Some cells were lysed directly with 1× SDS-PAGE loading buffer and loaded onto SDS–PAGE gels at 1 × 106 cells/lane. Gels were stained, fixed and dried, and radiolabeled proteins were detected by autoradiography. Meanwhile, some cells were lysed with buffer IPP150 (Rigaut et al. 1999) plus 1% Triton X-100 followed by trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitation, and the incorporated radioactivity was counted in a Beckman LS 6000 IC scintillation counter. Parallel incubations in the presence of 50 µg/mL CHX and counting were performed to eliminate the incorporation of radiolabel by processes other than cytoplasmic protein synthesis. Protein concentration was determined using Protein Assay Dye Reagent Concentrate (Bio-Rad) following the manufacturer's instructions. The proteins synthesized within 60 min were calculated for each sample as cpm/μg protein.

Polysome profile analysis

Of note, 2 × 109 of PF TbIF3a RNAi or TbIF3f RNAi cells in which RNAi was not induced or induced for 48 h were harvested immediately after addition of CHX to 0.1 mg/mL, and lysed with the buffer A (10 mM, pH 7.5, Tris–HCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 200 mM KCl, 100 µg/mL cycloheximide, 1 mM DTT) supplemented with 1% Triton X-100 and complete protease inhibitors (Roche). After centrifugation at 16,000g at 4°C for 15 min, the clear lysate was loaded onto 11 mL linear sucrose gradient (5% to 45% sucrose in the buffer A) and centrifuged at 38,000 rpm for 2.5 h at 4°C in a SW40 Ti rotor. Ninety-six gradient fractions were collected from the bottom to top by puncturing the centrifuge tube at the bottom, ∼0.1 mL per fraction. Polysome profiles were obtained by monitoring the absorbance of each fraction at 254 nm. Every eight fractions were combined and total RNAs were isolated by using TRIzol LS reagent (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The sedimentation profiles of rRNA were monitored on an agarose gel by EtBr staining.

Sucrose-gradient centrifugation and Western blot

Linear sucrose-gradient was made in buffer IPP150 instead of buffer A as described above. A total of 1 × 1010 of PF 3aRNAi-3f TAP or 3f RNAi-3a TAP cells with RNAi noninduced or induced were harvested and lysed with 10 mL buffer IPP150 containing 1% Triton X-100. One milliliter of the clear cell lysate was loaded onto the sucrose gradient and centrifuged as described above. Twelve fractions were collected from top to bottom and loaded on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred onto a PVDF membrane. The membrane was blocked in 10% nonfat milk powder in PBST (10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 h at room temperature, and then washed with PBST and probed with rPAP reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) against the protein A-tagged TbIF3a or TbIF3f (1:1000) for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was washed with PBST and the proteins were visualized using the ECL system. The residual 9 mL cell lysates were used for TAP purification. Similarly, the whole-cell lysates of PF TbIF3a-RNAi or TbIF3a RNAi-hsaIF3a TAP were separated on 8% SDS-PAGE gel for Western blot of the protein A-tagged hsaIF3a.

Luciferase reporter assay

Cell lysate was prepared using passive lysis buffer (Promega) and Rluc and Fluc luciferase activity was measured using the Dual Luciferase Assay kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

UV cross-linking combination with tandem affinity purification (CLiTAP)

CLiTAP was carried out to assess whether and which TbIF3 subunit could bind to RNA directly as described previously (Yue et al. 2014). Briefly, 2 × 109 of PF TbIF3a-TAP cells were harvested and irradiated by UV light at 254 nm followed by lysis with buffer IPP150 plus 1% Triton X-100, RNase T1 treatment and clarification by centrifugation. Through TAP purification, the TbIF3a-TAP complexes attached on the calmodulin beads were treated again with RNase T1 followed by [γ-32P]ATP (PerkinElmer) labeling RNA. Then the beads were boiled in 1× SDS-PAGE loading buffer and the denatured protein sample was separated on 10% SDS-PAGE gel followed by SYPRO Ruby staining according to the manufacturer's instructions (Life Technologies) and the radioactive signal was visualized by exposure to a phosphorimager (GE, Typhoon FLA 7000 IP).

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental material is available for this article.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Ken Stuart for providing the pZJM, pHD1344tub, and pHD1344-MHTAP plasmids and T. brucei PF 29-13 and BSF-SM strains. We also thank Dr. Guangxia Gao for providing the plasmids pNL4-3RL-CrPV-FL, pNL4-3RL-HCV-FL, and pNL4-3RL-EMCV-FL. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81171601) and the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (grant no. 2014A030313216).

Footnotes

Article is online at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.058651.116.

REFERENCES

- Aitken CE, Lorsch JR. 2012. A mechanistic overview of translation initiation in eukaryotes. Nat Struct Mol Biol 19: 568–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aylett CH, Boehringer D, Erzberger JP, Schaefer T, Ban N. 2015. Structure of a yeast 40S-eIF1-eIF1A-eIF3-eIF3j initiation complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol 22: 269–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangs JD, Crain PF, Hashizume T, McCloskey JA, Boothroyd JC. 1992. Mass spectrometry of mRNA cap 4 from trypanosomatids reveals two novel nucleosides. J Biol Chem 267: 9805–9815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beznoskova P, Cuchalova L, Wagner S, Shoemaker CJ, Gunisova S, von der Haar T, Valasek LS. 2013. Translation initiation factors eIF3 and HCR1 control translation termination and stop codon read-through in yeast cells. PLoS Genet 9: e1003962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnes J, Trotter JR, Ernst NL, Steinberg A, Stuart K. 2005. An essential RNase III insertion editing endonuclease in Trypanosoma brucei. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102: 16614–16619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhuri A, Maitra U, Evans T. 2013. Translation initiation factor eIF3h targets specific transcripts to polysomes during embryogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci 110: 9818–9823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- des Georges A, Dhote V, Kuhn L, Hellen CU, Pestova TV, Frank J, Hashem Y. 2015. Structure of mammalian eIF3 in the context of the 43S preinitiation complex. Nature 525: 491–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhalia R, Marinsek N, Reis CR, Katz R, Muniz JR, Standart N, Carrington M, de Melo Neto OP. 2006. The two eIF4A helicases in Trypanosoma brucei are functionally distinct. Nucleic Acids Res 34: 2495–2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z, Liu LH, Han B, Pincheira R, Zhang JT. 2004. Role of eIF3 p170 in controlling synthesis of ribonucleotide reductase M2 and cell growth. Oncogene 23: 3790–3801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z, Liu Z, Cui P, Pincheira R, Yang Y, Liu J, Zhang JT. 2009. Role of eIF3a in regulating cell cycle progression. Exp Cell Res 315: 1889–1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z, Qi J, Peng H, Liu J, Zhang JT. 2013. Spectrin domain of eukaryotic initiation factor 3a is the docking site for formation of the a:b:i:g subcomplex. J Biol Chem 288: 27951–27959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elantak L, Wagner S, Herrmannova A, Karaskova M, Rutkai E, Lukavsky PJ, Valasek L. 2010. The indispensable N-terminal half of eIF3j/HCR1 cooperates with its structurally conserved binding partner eIF3b/PRT1-RRM and with eIF1A in stringent AUG selection. J Mol Biol 396: 1097–1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire ER, Vashisht AA, Malvezzi AM, Zuberek J, Langousis G, Saada EA, Nascimento Jde F, Stepinski J, Darzynkiewicz E, Hill K, et al. 2014. eIF4F-like complexes formed by cap-binding homolog TbEIF4E5 with TbEIF4G1 or TbEIF4G2 are implicated in post-transcriptional regulation in Trypanosoma brucei. RNA 20: 1272–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Carnes J, Ernst NL, Winkler M, Stuart K. 2012. KREPB6, KREPB7, and KREPB8 are important for editing endonuclease function in Trypanosoma brucei. RNA 18: 308–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashem Y, des Georges A, Fu J, Buss SN, Jossinet F, Jobe A, Zhang Q, Liao HY, Grassucci RA, Bajaj C, et al. 2013. High-resolution cryo-electron microscopy structure of the Trypanosoma brucei ribosome. Nature 494: 385–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinnebusch AG. 2006. eIF3: a versatile scaffold for translation initiation complexes. Trends Biochem Sci 31: 553–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinnebusch AG. 2014. The scanning mechanism of eukaryotic translation initiation. Annu Rev Biochem 83: 779–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaskova M, Gunisova S, Herrmannova A, Wagner S, Munzarova V, Valasek L. 2012. Functional characterization of the role of the N-terminal domain of the c/Nip1 subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 3 (eIF3) in AUG recognition. J Biol Chem 287: 28420–28434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley LA, Sternberg MJ. 2009. Protein structure prediction on the Web: a case study using the Phyre server. Nat Protoc 4: 363–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieft JS. 2008. Viral IRES RNA structures and ribosome interactions. Trends Biochem Sci 33: 274–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolupaeva VG, Unbehaun A, Lomakin IB, Hellen CU, Pestova TV. 2005. Binding of eukaryotic initiation factor 3 to ribosomal 40S subunits and its role in ribosomal dissociation and anti-association. RNA 11: 470–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AS, Kranzusch PJ, Cate JH. 2015. eIF3 targets cell-proliferation messenger RNAs for translational activation or repression. Nature 522: 111–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerch M, Carnes J, Acestor N, Guo X, Schnaufer A, Stuart K. 2012. Editosome accessory factors KREPB9 and KREPB10 in Trypanosoma brucei. Eukaryot Cell 11: 832–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Dong Z, Yang Z, Chen Q, Pan Y, Yang Y, Cui P, Zhang X, Zhang JT. 2007. Role of eIF3a (eIF3 p170) in intestinal cell differentiation and its association with early development. Differentiation 75: 652–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mair G, Ullu E, Tschudi C. 2000. Cotranscriptional cap 4 formation on the Trypanosoma brucei spliced leader RNA. J Biol Chem 275: 28994–28999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Calvillo S, Nguyen D, Stuart K, Myler PJ. 2004. Transcription initiation and termination on Leishmania major chromosome 3. Eukaryot Cell 3: 506–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masutani M, Sonenberg N, Yokoyama S, Imataka H. 2007. Reconstitution reveals the functional core of mammalian eIF3. EMBO J 26: 3373–3383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews KR, Tschudi C, Ullu E. 1994. A common pyrimidine-rich motif governs trans-splicing and polyadenylation of tubulin polycistronic pre-mRNA in trypanosomes. Genes Dev 8: 491–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meleppattu S, Kamus-Elimeleh D, Zinoviev A, Cohen-Mor S, Orr I, Shapira M. 2015. The eIF3 complex of Leishmania-subunit composition and mode of recruitment to different cap-binding complexes. Nucleic Acids Res 43: 6222–6235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Methot N, Song MS, Sonenberg N. 1996. A region rich in aspartic acid, arginine, tyrosine, and glycine (DRYG) mediates eukaryotic initiation factor 4B (eIF4B) self-association and interaction with eIF3. Mol Cell Biol 16: 5328–5334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moura DM, Reis CR, Xavier CC, da Costa Lima TD, Lima RP, Carrington M, de Melo Neto OP. 2015. Two related trypanosomatid eIF4G homologues have functional differences compatible with distinct roles during translation initiation. RNA Biol 12: 305–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opperdoes FR. 1994. The trypanosomatidae: amazing organisms. J Bioenerg Biomembr 26: 145–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panigrahi AK, Schnaufer A, Ernst NL, Wang B, Carmean N, Salavati R, Stuart K. 2003. Identification of novel components of Trypanosoma brucei editosomes. RNA 9: 484–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisarev AV, Hellen CU, Pestova TV. 2007. Recycling of eukaryotic posttermination ribosomal complexes. Cell 131: 286–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisarev AV, Kolupaeva VG, Yusupov MM, Hellen CU, Pestova TV. 2008. Ribosomal position and contacts of mRNA in eukaryotic translation initiation complexes. EMBO J 27: 1609–1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pukala TL, Ruotolo BT, Zhou M, Politis A, Stefanescu R, Leary JA, Robinson CV. 2009. Subunit architecture of multiprotein assemblies determined using restraints from gas-phase measurements. Structure 17: 1235–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Querol-Audi J, Sun C, Vogan JM, Smith MD, Gu Y, Cate JH, Nogales E. 2013. Architecture of human translation initiation factor 3. Structure 21: 920–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezende AM, Assis LA, Nunes EC, da Costa Lima TD, Marchini FK, Freire ER, Reis CR, de Melo Neto OP. 2014. The translation initiation complex eIF3 in trypanosomatids and other pathogenic excavates—identification of conserved and divergent features based on orthologue analysis. BMC Genomics 15: 1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigaut G, Shevchenko A, Rutz B, Wilm M, Mann M, Seraphin B. 1999. A generic protein purification method for protein complex characterization and proteome exploration. Nat Biotechnol 17: 1030–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel TN, Hekstra DR, Kemp LE, Figueiredo LM, Lowell JE, Fenyo D, Wang X, Dewell S, Cross GA. 2009. Four histone variants mark the boundaries of polycistronic transcription units in Trypanosoma brucei. Genes Dev 23: 1063–1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel TN, Hekstra DR, Wang X, Dewell S, Cross GA. 2010. Genome-wide analysis of mRNA abundance in two life-cycle stages of Trypanosoma brucei and identification of splicing and polyadenylation sites. Nucleic Acids Res 38: 4946–4957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokabe M, Fraser CS, Hershey JW. 2012. The human translation initiation multi-factor complex promotes methionyl-tRNAi binding to the 40S ribosomal subunit. Nucleic Acids Res 40: 905–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C, Todorovic A, Querol-Audi J, Bai Y, Villa N, Snyder M, Ashchyan J, Lewis CS, Hartland A, Gradia S, et al. 2011. Functional reconstitution of human eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 (eIF3). Proc Natl Acad Sci 108: 20473–20478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C, Querol-Audi J, Mortimer SA, Arias-Palomo E, Doudna JA, Nogales E, Cate JH. 2013. Two RNA-binding motifs in eIF3 direct HCV IRES-dependent translation. Nucleic Acids Res 41: 7512–7521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valasek L, Mathew AA, Shin BS, Nielsen KH, Szamecz B, Hinnebusch AG. 2003. The yeast eIF3 subunits TIF32/a, NIP1/c, and eIF5 make critical connections with the 40S ribosome in vivo. Genes Dev 17: 786–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villa N, Do A, Hershey JW, Fraser CS. 2013. Human eukaryotic initiation factor 4G (eIF4G) protein binds to eIF3c, -d, and -e to promote mRNA recruitment to the ribosome. J Biol Chem 288: 32932–32940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner S, Herrmannova A, Malik R, Peclinovska L, Valasek LS. 2014. Functional and biochemical characterization of human eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 in living cells. Mol Cell Biol 34: 3041–3052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Morris JC, Drew ME, Englund PT. 2000. Inhibition of Trypanosoma brucei gene expression by RNA interference using an integratable vector with opposing T7 promoters. J Biol Chem 275: 40174–40179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen F, Zhou R, Shen A, Choi A, Uribe D, Shi J. 2012. The tumor suppressive role of eIF3f and its function in translation inhibition and rRNA degradation. PLoS One 7: e34194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz E, Leal S, Ochatt C, Cross GA. 1999. A tightly regulated inducible expression system for conditional gene knock-outs and dominant-negative genetics in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Biochem Parasitol 99: 89–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin JY, Dong ZZ, Liu RY, Chen J, Liu ZQ, Zhang JT. 2013. Translational regulation of RPA2 via internal ribosomal entry site and by eIF3a. Carcinogenesis 34: 1224–1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue S, Zhou S, Guo X. 2014. Efficient assay of the RNA-binding activities in a protein complex by UV cross-linking and tandem affinity purification. Prog Biochem Biophys 41: 617–621. [Google Scholar]

- Zamudio JR, Mittra B, Campbell DA, Sturm NR. 2009. Hypermethylated cap 4 maximizes Trypanosoma brucei translation. Mol Microbiol 72: 1100–1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng L, Wan Y, Li D, Wu J, Shao M, Chen J, Hui L, Ji H, Zhu X. 2013. The m subunit of murine translation initiation factor eIF3 maintains the integrity of the eIF3 complex and is required for embryonic development, homeostasis, and organ size control. J Biol Chem 288: 30087–30093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Pan X, Hershey JW. 2007. Individual overexpression of five subunits of human translation initiation factor eIF3 promotes malignant transformation of immortal fibroblast cells. J Biol Chem 282: 5790–5800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C, Arslan F, Wee S, Krishnan S, Ivanov AR, Oliva A, Leatherwood J, Wolf DA. 2005. PCI proteins eIF3e and eIF3m define distinct translation initiation factor 3 complexes. BMC Biol 3: 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Sandercock AM, Fraser CS, Ridlova G, Stephens E, Schenauer MR, Yokoi-Fong T, Barsky D, Leary JA, Hershey JW, et al. 2008. Mass spectrometry reveals modularity and a complete subunit interaction map of the eukaryotic translation factor eIF3. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105: 18139–18144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Wang X, Goff SP, Gao G. 2012. Translational repression precedes and is required for ZAP-mediated mRNA decay. EMBO J 31: 4236–4246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.